Abstract

There is an increasing trend in bribery practices among employees (corporate bribery), especially from emerging economies, where developed countries, including the USA, have enormous interests in various aspects of local and international trade. Therefore, this study aims to examine the influence of organisations’ culture and outcome orientation, as well as the stability culture dimensions of Organisation Culture Profile (OCP), in order to combat corporate bribery practices, as an aspect of corporate sustainability practices, and their subsequent impact on both organisational financial and non-financial performance. The study surveyed mid-to-top level managers of a total of 201 organisations from Bangladesh. The survey data were used to develop a structural equation model (SEM) by utilising the AMOS (26th version) software, and thus tested the developed hypotheses on the study variables. The findings provide evidence of the positive influence of the two dimensions (outcome orientation and stability) of organisations’ culture in combating bribery practices within organisations. The findings highlight the positive impact of combating bribery practices on both organisations’ financial and non-financial performance. Our empirical findings contribute to the existing limited bribery-related corporate sustainability literature, with the goal of achieving suitable organisation culture in order to minimise unethical business practices, specifically bribery practices. The findings provide practical implications for practitioners and policymakers due to the discovery of the importance of having congenial corporate culture, in order to promote and enhance corporate sustainability practices by reducing the likelihood of poor practices by employees, i.e., taking or offering bribes to business partners.

1. Introduction

Organisations in the twenty-first century are under tremendous pressure from various stakeholders to operate and run organisations in a sustainable manner so that the interests of organisations’ stakeholders are preserved without harming the interests of future stakeholders [1,2,3]. Although corporate sustainability is now being treated by many organisations, especially those from developed countries, as a strategic priority, its practice, especially from the ethical business practice perspective, is less likely to be observed by companies in developing and underdeveloped countries. More specifically, there is an increasing trend of unethical business practices, such as taking and/or offering bribes and small felicitations for business operations by employees in developing and under-developed countries, such as Bangladesh, SriLanka and Pakistan [4,5,6,7]. According to the 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), more than two thirds of 180 countries across the globe failed to prevent corruption, while Bangladesh has been ranked 147th out of the 180 countries [8]. More specifically, bribery is a common practice for businesses in Bangladesh, especially in utilities, tax payments and external trades [9]. Similarly, according to the 2022 TRACE Bribery Risk Matrix, which measures business bribery risk in 194 jurisdictions, Bangladesh has been ranked 153rd out of 194 countries across the world, with a high-risk score of 64 [10]. Consequently, overall sustainable business practices seem poor across the world, and in Bangladesh in particular. Although the existing sustainability literature has paid relatively more attention to the different aspects of sustainability practices, such as the environmental and economic aspects, less attention has been paid to the bribery aspect of sustainable business practices. Specifically, there is a limited understanding of what factors could minimise unethical business practices (bribery practices) and how they could do so, and could thus promote sustainable practices. Given the multifarious consequences of bribery practices, it is now important to identify and examine the factors preventing and minimising bribery practices in the corporate environment. Therefore, this study aims to examine the factor/s that may be useful in preventing bribery practices by employees in developing countries, and thus shed light on the aforementioned research gap.

It is evident that organisational culture has a substantial impact on business operations, practices, achieving business objectives and performance [11,12,13]. Organisational culture evolves and is established within an organisation or any component of an organisation over time, and guides and coordinates members’ behaviour and holds the organisation together [6,14,15]. It shapes employees’ behaviour within the organisation in performing their regular duties. Moreover, conducive organisational culture is directly linked to the morale of employees, which may be a driving force to combat bribery practices within organisations. Previous studies have examined the influence of organisational culture on organisational practices and state its importance for the successful implementation of a variety of organisational practices and changes [12,16]. However, how organisational culture is associated with corporate sustainability practices has been paid little attention in the sustainability literature [17]. Hence, this study addresses the research question: “Does organisational culture influence corporate sustainability practices, such as combating corporate bribery practices?”. Accordingly, this study aims to examine the influence of organisational culture (outcome orientation and stability culture dimensions of (O’Reilly et al., 1991) [18] the Organisational Culture Profile (OCP) on combating bribery practices.

Provided that the achievement of an organisation’s objectives is the key to its sustainability practices, as well as the growing interests of different stakeholders in developing insights into the impact of sustainability practices on organisational performance, it is important to develop insights into what is the impact of corporate sustainability practices on an organisation’s performance. Although researchers have examined the impact of corporate sustainability practices on organisational performance [19], combating the bribery aspect of sustainability has been paid little attention. Accordingly, this study aims to further examine the impact of corporate sustainability, focusing on combating the bribery aspect and how this has an effect on organisational financial and non-financial performance. It is thus hoped to minimise the paucity of research on the antecedents of sustainability practices, and the relationship between sustainability practices and organisational performance [20].

The findings of this empirical study contribute to the existing limited bribery-related corporate sustainability literature, with the role of suitable corporate culture in minimising unethical business practices: minimising bribery practices and the impact of such practices on an organisation’s financial and non-financial performance. The findings of this study contribute to the relevant literature in the following ways: first, it empirically exhibits the influence of an organisation’s culture (outcome orientation and stability in particular) to combat bribery practices, and thus promote corporate sustainability practices, and thereby contribute to the limited literature in the field of interest. Second, this study provides empirical evidence of the impact of corporate sustainability practices on both organisational financial and non-financial performance. Third, the findings of this study provide policymakers with empirical insights into the antecedents of combating bribery practices, which can be useful for promoting corporate sustainability practices and its subsequent impact on the organisation’s financial and non-financial performance.

The remainder of this study is arranged as follows: Section 2 highlights the literature review and hypotheses of the study. Section 3 discusses the method of the study, including sample selection and data collection, variable measurements, and common method biases. In Section 4, the empirical results are reported along with the robustness and endogeneity check. Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Corporate Culture and Its Dimensions

Corporate culture refers to “the pattern of basic assumptions that a given group has invented, discovered, or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external and internal integration and that have worked well enough to be considered valid, and is therefore to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to these problems” [21] (p. 3). Researchers from different disciplines reveal different dimensions of corporate culture [3,14,22,23]. This study follows the way O’Reilly et al., 1991 [18], define corporate culture’s dimensions. O’Reilly et al., 1991 [18], identify six different cultural dimensions, such as respect for people, outcome orientation, team orientation, innovation, attention to detail, and stability. The O’Reilly et al., 1991 [18], culture dimensions are popular to researchers from various disciplines [16,21,24,25,26]. This study focuses on two of the six dimensions of corporate culture, namely outcome orientation and stability culture, in order to examine their association with the bribery aspect of corporate sustainability practices. Outcome orientation culture refers to “the degree to which management focuses on results or outcomes rather than on the techniques, and the processes used to achieve them” [27] (p. 513) [28]. Stability culture is defined as “the degree to which organisational activities emphasise maintaining the status quo in contrast to growth” [27] (p. 513) [28].

2.2. Corporate Sustainability and Its Dimensions

The term “corporate sustainability” is complex to define, and thus a congruent definition of corporate sustainability is lacking [18,29,30]. Based on a review of the corporate sustainability literature, Montiel and Delgado-Ceballos, 2014 [31], define corporate sustainability as a tri-dimensional construct, which includes economic, social, and environmental aspects. This study follows one of the most recent definitions given by Valente, 2012 [32]. Valente, 2012, [32] (p. 586) defines corporate sustainability from the perspective of the “sustain-centric” orientation of the firm, “which is described as a step toward a proactive orientation to sustainability […] to find ways to interconnect social, economic, and ecological systems, using coordinated approaches that harness the collective cognitive and operational capabilities of multiple local and global social, ecological, and economic stakeholders operating as a unified network or system”.

Researchers highlight various dimensions of corporate sustainability [33] practices. To address the aforementioned three constructs of corporate sustainability, Szekely and Knirsch, 2005 [13], list its 10 different dimensions, namely economic growth, shareholder value, prestige, corporate reputation, customer relationships, product quality, ethical business practices, sustainable job creation, value creation for all stakeholders, and attention to the need for the underserved stakeholders. Though this study agrees on the need to sustain all these different dimensions, it seems overwhelming for us to measure firms’ corporate sustainability in respect to all dimensions [14]. Thus, our study pays attention to the ethical business practice dimension of corporate sustainability, i.e., the bribery aspect of corporate sustainability.

2.3. Corporate Bribery

Corporate sustainability practices are affected by numerous negative phenomena that interrupt the corporate sustainability performance and exacerbate the possibility of ensuring commitment to social good and firm reputation, which result in various drawbacks for the wider community [34]. However, the commitment to the social good may be useful for constraining corporate employees’ greed. One of the challenges that the modern business environment experiences is corporate bribery.

Veselovská et al., 2020, [21] (p. 1972) define corporate bribery as “being symbiotic with broken ethical principles and criminal activities. Both present serious issues on their own; however, they represent a critical problem for organisations and their employees”. A recent World Bank report published that USD 1 trillion annually accounts for 5% of the GDP, funded as bribery by individuals and firms [34,35]. Therefore, the risk of corporate bribery in the corporate sector is a critical issue that must be challenged. The CSR literature suggests that corporations that participate in corporate sustainability activities are less inclined to be involved in corporate corruption [36,37]. Thus, corporations must fight against bribery to ensure sustainable social and economic development [3]. When a firm engages in high-level CSR activities, it is expected to be ethically responsible and less likely to be involved in corruption risk, such as bribery [34]. Although the governments of many emerging countries, including Bangladesh, have undertaken several initiatives to enhance transparency and integrity in business operations, bribery issues, specifically with public services, are still continuing [38]. Corporate bribery practices by public service organisations impede their performances, damage the organisations’ reputation and boost up the costs of transactions [3]. According to Abdullah et al., 2018 [39], there is an association between the quality of governance practices, such as employee attitude towards corporate ethics, and integrity is likely to reduce a firm’s exposure to corporate bribery risk.

2.4. Association between Outcome-Orientated Organisation Culture and Combating the Bribery Aspect of Corporate Sustainability

Employees from outcome-oriented organisations pay attention to the results of actions and achievements [40], and expect rewards for their actions, efforts, and behaviour accordingly. Similarly, researchers posit that employees emphasize the different aspects and outcomes in their pursuit of corporate sustainability [41]. Accordingly, it is expected that employees are less likely to be involved in unfair business practices, such as taking bribes, and thus promote corporate sustainability if they are being treated fairly on the basis of their own individual performance. Researchers also highlight the importance of the existence of outcome orientation culture to promote corporate sustainability [16,41,42]. Hence, we assume that the existence of outcome-orientated culture in organisations will drive employees to abstain from taking and offering bribes from/to different stakeholders. Therefore, we hypothesise that:

H1:

There is a significantassociation between outcome orientation andcombating the bribery aspect of corporate sustainability.

2.5. Association between Organisation Stability Culture and Combating the Bribery Aspect of Corporate Sustainability

Employees in organisations where stability culture is being practiced value stability [43]. Such stability includes the stability/security of employment, and financial and leadership stability, being calm and low-conflict [25,43]. It is logical to assume that the existence of stability culture will promote employees not to involve in taking/offering illegal financial benefits in exchange for rendering and/or receiving services. This is because financial or job security reduces the risk of facing financial hardship in the future, which leads employees not to be reckless to generate illegal money for future safety. Accordingly, we assume that the existence of stability culture reduces the likelihood of participating in bribery practices, and thus enhances corporate sustainability practices. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H2:

There is a significantassociation between stability culture andcombating the bribery aspect of corporate sustainability.

2.6. Association between Combating the Bribery Aspect of Corporate Sustainability and Organisational Financial and Non-Financial Performance

The existing literature on corporate sustainability examines the association between corporate sustainability and the organisation’s financial performance, and finds the positive association between them in terms of return on equity (ROE), Tobin’s Q, the return on assets (ROA), market share, gross profit margin, firm value, and stock returns [7,12,17,19,20,38,44,45]. For instance, Bhuiyan et al., 2020 [12], found that corporate sustainability practices, with respect to minimising illegal business activities, are positively associated with organisations’ financial performance. Furthermore, a review of the literature highlights a positive association between corporate sustainability practices and an organisation’s non-financial performance in terms of corporate reputation, innovation and differentiation [46,47], customer satisfaction [48], and employee commitment [49]. For instance, Bhuiyan et al., 2020 [12], found that corporate sustainability practices relating to the minimising illegal business activities are positively associated with the non-financial performance, such as product quality and customer retention rate. Accordingly, it is expected that combating bribery-related corporate sustainability practices might result in both higher financial and non-financial performance. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H3:

Combating the bribery aspect of corporate sustainability has a significant association with organisational financial performance.

H4:

Combating the bribery aspect of corporate sustainability has a significant association with organisational non-financial performance.

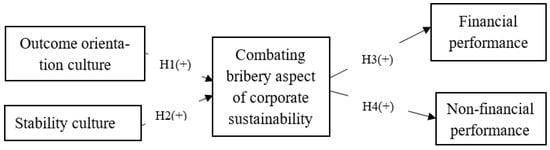

A conceptual model of the study, along with the hypotheses developed above, has been demonstrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the study variables.

3. Method

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

This quantitative research surveyed a total of 460 organisations across various industries in Bangladesh identified in the Dun & Bradstreet dataset [50]. The list of organisations for the survey was prepared using the Dun & Bradstreet Hoovers database [6] on the basis of the organisations operating in Bangladesh, having more than or equal to fifty full-time employees, which resulted in a total of 460 organisations. A mail survey was administered to one middle- or higher-level executive from each of the 460 organisations. To administer the survey, this study followed (Dillman, 2011) [51] a tailored design method, and thus the sent survey instruments consisted of a cover letter, questionnaire, and self-addressed return envelope to the sampled organisations. Responses from a total of 201 organisations were received, which account for a response rate of 43.7%. Responses were received mostly from manufacturing organisations (140 organisations, which accounts for 69.65%), followed by service-oriented organisations (57 organisations, which account for 28.36%) (see Table 1). The majority of the organisations (176 organisations, or 87.6%) were domestic, while 25 organisations (12.43%) were multinational.

Table 1.

A summary of response rates and respondents, and their organisation’s demographic statistics.

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Corporate Culture

Outcome orientation and stability culture dimensions were measured with seven and three items, respectively, adapted from (O’Reilly et al., 1991) [18] the Organisational Culture Profile (see Appendix A). The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted with ten items under two culture dimensions. The CFA results indicate a poor model fit to the dataset (CMIN/DF = 3.57; GFI = 0.888; AGFI = 0.818; CFI = 0.882; RMSEA = 0.113; SRMR = 0.066). After re-specifications of the model by connecting error terms based on modification indices, we found a final model with an acceptable level of the goodness of fit indices(the recommended threshold scores for the assessment of good SEM model fit to the data set are CMIN/DF < 5.0; GFI > 0.90; AGFI > 0.80; CFI > 0.90 [52]): CMIN/DF = 2.180; GFI = 0.936; AGFI = 0.887; CFI = 0.951; RMSEA = 0.077; SRMR = 0.048. The Cronbach alpha reliability scores (α) of the seven-item outcome orientation and three-item stability culture measures are 0.824 and 0.745, and thus exceeded the minimum cut-off of 0.70 [47].

3.2.2. Combating the Bribery Aspect of Corporate Sustainability

A six-item construct based on the OECD (2011) [6] seven principles relating to the combating bribery was used to measure the extent to which combating the bribery aspect of corporate sustainability was being practiced within the sampled organisations (see Appendix A). The respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which each item explained the current organisational practices on a five-point Likert scale, with the anchors of 1 ‘Not at all’ and 5 ‘To a great extent’. In order to validate this measure, we conducted CFA. The initial model CFA results (CMIN/DF = 2.331; GFI = 0.967; AGFI = 0.924; CFI = 0.977; RMSEA = 0.082; SRMR = 0.030) indicate a good model fit to the dataset. The Cronbach alpha score (α = 0.866) of the six-item measure exceeded the minimum cut-off of 0.70.

3.2.3. Organisation Performance

“Organisation performance” was measured from the perspective of both financial and non-financial aspects. A three-item construct for each of the financial and non-financial performance was adapted from Kaynak and Kara, 2004 [53]. The results of the initial model CFA (CMIN/DF = 3.446; GFI = 0.956; AGFI = 0.886; CFI = 0.963; RMSEA = 0.111; SRMR = 0.037) indicated a poor model fit to the dataset. Re-specification of the model was then taken after deleting one item: “we have a lower employee turnover rate than our competitors” from the non-financial performance measure because its factor loading score (0.38) was less than the acceptable limit of 4.0 to be considered for the CFA analysis. The revised CFA model with the five items under both measures provided a good model fit to the dataset: CMIN/DF = 5.791; GFI = 0.957; AGFI = 0.841; CFI = 0.962; RMSEA = 0.155; SRMR = 0.031. The Cronbach alpha reliability scores (α) of the 3-item financial performance measure and the two-item non-financial performance measure were 0.892 and 0.71, respectively, and hence met the minimum cut-off score of 0.70.

3.3. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

In addition to the content validity of the measures of this study tested by the CFA, we tested the convergent and discriminant validity of the measures. The convergent validity of the measures was tested with respect to their path coefficients, standard errors (S.E.), and t-values [54]. The estimated factor loadings of all the measures are more than twice their respective S.E., and their t-values (t > 2) are significant at the level of 0.01 (see Appendix A for all measures), and composite reliability scores of all measures are more than 0.90, thereby supporting their convergent validity of the measures. The discriminant validity of the measures was tested by comparing the measures’ (Cronbach’s, 1951) [55] alpha reliability scores with their correlations, with the other scales of the study. The scales’ reliability scores are higher than their correlations with other scales (see Table 2), and thus provide evidence of the presence of the discriminant validity of the measures.

Table 2.

Inter-construct correlation, descriptive statistics, and Cronbach alphas and composite reliability scores.

3.4. Common Method Bias Test

As suggested by Podsakoff et al., 2003 [50], this study followed numerous pre-survey techniques to minimise the likelihood of common method bias problems, including an extensive review of the literature to come up with established and validated scales to measure the variables of this study, drafting a questionnaire with a simple and easy language with the necessary clarification that helps minimise ambiguity, and mentioning that the respondent’s identity will be kept confidential. This entire process indicates that social desirability bias is less likely of an issue in this study [32].

In addition, this study employed a post-survey technique to check common method bias issues, if any were present. In this regard, we conducted Harman’s (1967) one (single)-factor test [40]. The exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (varimax rotation) was resulted in four factors having eigenvalues of more than 1, and explained 61.02% of the total variance of 100%. While no factor (31.58% maximum) was explained by more than or equal to 50% of the total variance, thereby indicating that a common method bias is less likely an issue in this study.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Structural Equation Model

We developed structural equation modelling (SEM) by utilising the AMOS software, as suggested by Hair et al., 2010 [52]. We conducted CFA models first and then the SEM. We first developed a base model. The base model results are reported under “Model A” in Table 3. The base model’s goodness-of-fit indices indicated a poor model fit to the data set: CMIN/DF = 2.874; GFI = 0.819; AGFI = 0.772; CFI = 0.807.

Table 3.

Summary of SEM results.

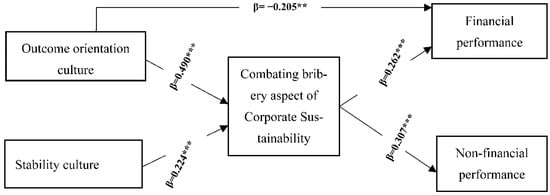

The initial model was revised by connecting error terms based on the highest possible modification indices recommended by Anderson and Gerbing, 1988 [54], and resulted in a good model fit to the dataset: (CMIN/DF = 2.467; GFI = 0.874; AGFI = 0.803; CFI = 0.953) (see Figure 2 and Model B in Table 3).

Figure 2.

Results of the structural equation model among the study variables. Note: *** and ** indicate statistical significance at 0.01 and 0.05 levels, respectively (2-tailed).

4.1.1. Association between Outcome-Orientated Corporate Culture and the Bribery Combating Aspect of Corporate Sustainability

The SEM results reported in Figure 2 and Table 3 (Model B) reveal that the outcome-oriented culture is significantly and positively associated with the bribery combating aspect of corporate sustainability (β = 0.490; p = 0.000). Hence, hypothesis H1 is supported. The findings indicate that the culture of promoting competitiveness among employees, responding to their high expectations of performance, as well as providing them rewards based on their individual performance may refrain them to take bribes from and/or offer bribes to business partners. Hence, organisations that want to combat bribery practices, and thus promote corporate sustainability practices, are suggested to pay attention to develop an outcome-oriented culture by developing a culture of respecting employees’ high expectations of performance, providing them rewards based on performance, and motivating them to be action-oriented. Our findings are in line with what other researchers discourse about the role of organisational outcome orientation culture on corporate sustainability practices [41,42]. Researchers [48,56] argue that the existence of outcome orientation culture is likely to promote employee sustainability practices. Our empirical findings contribute to the existing sustainability literature, with insights into the role of suitable organisation culture towards enhancing sustainability practices.

4.1.2. Association between Organisation Stability Culture and the Bribery Combating Aspect of Corporate Sustainability

The SEM results reported in Figure 2 and Table 3 (Model B) highlighted that organisational stability culture is significantly and positively associated with the bribery combating aspect of corporate sustainability (β = 0.224; p = 0.003). Hence, hypothesis H2 is supported. Furthermore, the associations between the stability culture and organisational financial (β = −0.006; p = 0.945) and non-financial performance (β = −0.050; p = 0.571) are statistically insignificant. The findings indicate that organisational stability culture has a positive influence on combating bribery practices in organisations. More specifically, if organisations provide employment security, bribery and small facilitation payment seems to be less likely to occur in organisations. This is because job security may lead employees not to be worried too much about the future, and thus there may have less tendency to make money illegally and abruptly by using organisational identity. Accordingly, organisations are advised to build a stability culture by providing employees with job security, and thus enhance corporate sustainability practices by reducing illegal and unethical practices, including taking and offering bribes. These findings contribute to the very limited corporate sustainability literature with the role of stability culture towards promoting corporate sustainability practices. Thus, the findings could be useful for organisational decision makers and policymakers, to devise suitable polices to combat bribery practices.

4.1.3. Association between the Bribery Combating Aspect of Corporate Sustainability and Organisational Financial and Non-Financial Performance

As reported in Figure 2 and Table 3 (Model B) and summarised in Table 4 Panel B, the bribery combating aspect of corporate sustainability practices is significantly and positively associated with financial performance (β = 0.262; p = 0.007) and non-financial performance (β = 0.307; p = 0.004). Hence, both hypotheses H3 and H4, are supported. The findings indicate that the bribery combating aspect of corporate sustainability practices drives organisations towards achieving their short-term financial goals, such as profit, sales, and ROI goals, as well as long-term strategic (non-financial goals) goals, such as the goal of ensuring high-quality product and service offering and the goal of achieving a higher customer retention rate than competitors. These findings conform with what previous studies found (see [2,8,9,10,41,52]). For example, Bhuiyan et al., 2020 [12], found a positive association of corporate sustainability practices (minimising the illegal activities aspect of sustainability practices) with organisations’ financial performance. While others [46,47,57] found a positive association between corporate sustainability practices and organisation non-financial performance, such as reputation, innovation and differentiation, customer satisfaction, and employee commitment. Therefore, the findings of the study may be useful for attracting the attention of policymakers and organisational decision makers in order to minimise the likelihood of bribery practices, and thus enhance organisational performance.

Table 4.

Summary of SEM results with control the organisation size (number of employees) as the control variable.

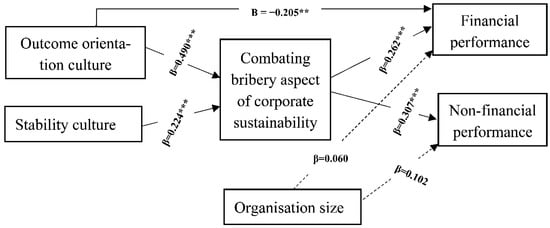

4.2. Robustness and Endogeneity Check of the Base SEM Results

This study revised the base SEM model by including organisation size (in terms of the number of full-time employees) in the model as a control variable to check the robustness of the results of the base SEM model, as reported in Table 3 (Model B). The results of the new model (see Table 4 and Figure 3) indicate that the organisation size does not exhibit a significant association with any of the performance indicators: financial and non-financial performance. The new SEM model also provided results similar to what we found from the base SEM model reported in Table 3 (Model B), thus indicating the robustness of the findings of the base SEM model. Accordingly, we can conclude that endogeneity is less likely to occur in our study (Table 3, Model B).

Figure 3.

Results of the structural equation model among the study variables with the control variable (organisation size). Note: *** and ** indicate statistical significance at 0.01 and 0.05 levels, respectively (2-tailed).

5. Concluding Remarks

This study aimed at examining the influence of corporate culture on combating bribery practices, an aspect of corporate sustainability, and its subsequent impact on organisational performance. This survey-based quantitative study was based on the responses from a total of 201 mid-to-high level managers employed in Bangladeshi organisations. The survey data were analysed for SEM by employing the AMOS software. The findings highlight the importance of corporate culture: outcome orientation and stability cultures on combating bribery practices within organisations. The findings also provide evidence of positive associations between the combating bribery aspect of corporate sustainability practices and organisational financial and non-financial performance.

The evidence of corporate-level bribery practices provides interesting findings relating to its practical implications and the ability of the corporations to enhance their CSR engagement. This paper offers several policy implications. The regulators from emerging countries may move to mandatory CSR disclosure and investment from voluntary CSR practices by corporations. Given the social responsibility motivation of CSR, this study opens an arena of CSR as a medium of anti-corporate bribery behaviour. This study has an impact on substantial policy implications for emerging markets, such as encouraging corporations, stakeholders, ethical consumers, socially sensible investors, creditors and regulatory bodies to reciprocally cooperate for the benefits of CSR commitments, as a tool to restrict the risk of corporate-level bribery. The positive impact of CSR commitments may support resolving agency conflict between corporations, shareholders and society [37].

Similar to the other survey-based studies, this study is under the general limitation of survey-based research [58]. First, the determination of the causal relationships among variables is hard and treated as a common issue in the survey-based study [31]. Hence, future quantitative studies based on archival and/or panel data (longitudinal data) may improve generalisability of the findings within the field of this study [31,59,60]. Second, the study collected data from a respondent from each of the sampled organisations, which may raise the issue of representation of the company to which the respondent belongs. Accordingly, future studies based on the responses from multiple respondents from the same organisation may improve the accuracy of the findings of the study.

6. Implications

The findings of this empirical study contribute theoretically to the existing limited corporate sustainability literature, with insights into the role of suitable organisation culture, such as outcome orientation and stability culture on minimising bribery practices within the corporate environment. The findings also contribute theoretically to the corporate sustainability literature, with insights into the impact of sustainability practices towards enhancing the organisation financial and non-financial performance.

The findings of this study provide corporate practitioners and policymakers with practical implications of the importance of having a congenial corporate culture to promote and enhance corporate sustainability practices by reducing the likelihood of employees’ ill practices, such as taking or offering bribes from/to organisations’ business partners. This proposal of combating firm-level corporate bribery represents a comprehensive and innovative approach to the risk mitigation of the bribery impact on both financial and non-financial performance. Therefore, regulators and organisational policy implementors can create force on organisations to engage in high-level socially responsible activities to prohibit bribery and corruption. The understanding of such engagement is commendable and leads a clear path for other economies and corporations to move forward in corporate sustainability, and implement outcome orientation and stability within corporate culture towards limiting corporate-level bribery through sustainable and accountable business practices.

Author Contributions

Methodology, F.B.; Resources, P.M.; Data curation, F.B.; Writing—original draft, M.M.R., F.B. and I.M.; Supervision, M.M.R. and M.S.; Project administration, M.M.R.; Funding acquisition, M.S., P.M. and I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Primary data is used, and questionnaire items are attached in Appendix A.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interests among the authors.

Appendix A. Questionnaire Items and CFA Statistics

The items retained after confirmatory factor analysis are shown below. The parameter 1 (one) was assigned as fixed on one item of each construct/scale in AMOS, which had the highest unstandardised estimate, and hence no t-value, as well as the value of S. E. is shown in the model.

| Constructs and Items | Factor Loading | t-Value | S.E. | Cronbach Alpha |

| 1. Organisational Culture | ||||

| 1.1 Outcome Orientation | 0.824 | |||

| Being competitive | 0.561 *** | n/a | n/a | |

| Being achievement-oriented | 0.575 *** | 6.294 | 0.165 | |

| Having high expectations for performance | 0.500 *** | 6.576 | 0.117 | |

| Being result-oriented | 0.681 *** | 7.053 | 0.161 | |

| Being analytical | 0.656 *** | 6.902 | 0.177 | |

| Being action-oriented | 0.534 *** | 5.997 | 0.162 | |

| Being rule-oriented | 0.751 *** | 7.474 | 0.178 | |

| 1.2 Stability | 0.745 | |||

| Security of employment | 0.545 ** | n/a | n/a | |

| Stability | 0.708 *** | 9.267 | 0.143 | |

| Predictability | 0.688 *** | 6.957 | 0.199 | |

| Goodness of Fit: CMIN/DF = 2.180; GFI = 0.936; AGFI = 0.887; CFI = 0.951; RMSEA = 0.077; SRMR = 0.048 | ||||

| 2. Combating Bribery Aspect of Corporate Sustainability | ||||

| Our company: | 0.866 | |||

| -does not offer, give or accept undue financial, non-monetary or other advantage to/from public officials or the employees of business partners. | 0.666 *** | n/a | n/a | |

| -has developed/adopted adequate internal controls, ethics and compliance programs or measures for preventing and detecting bribery. | 0.807 *** | 9.631 | 0.124 | |

| -prohibits or discourages the use of small facilitation payments. | 0.735 *** | 8.947 | 0.106 | |

| -accurately records small facilitation payments, if occurred, in books and financial records. | 0.786 *** | 9.441 | 0.101 | |

| -takes adequate measures to minimise the likelihood of bribery. | 0.748 *** | 9.080 | 0.123 | |

| -promotes employee awareness of and compliance with company policies and management control mechanisms against bribery. | 0.611 *** | 7.642 | 0.120 | |

| Goodness of Fit: CMIN/DF = 2.331; GFI = 0.967; AGFI = 0.924; CFI = 0.977; RMSEA = 0.082; SRMR = 0.030 | ||||

| 3. Organisational Performance | ||||

| 3.1 Financial performance | 0.892 | |||

| Profit goals have been achieved. | 0.851 *** | n/a | n/a | |

| Sales goals have been achieved. | 0.853 *** | 14.345 | 0.070 | |

| Return on investment (ROI) goals have been achieved. | 0.865 *** | 14.583 | 0.073 | |

| 3.2 Non-financial performance | 0.710 | |||

| Our products/services are of a higher quality than those of our competitors. | 0.635 *** | n/a | n/a | |

| We have a higher customer retention rate than our competitors. | 0.866 *** | 6.632 | 0.204 | |

| Goodness of Fit: CMIN/DF = 5.791; GFI = 0.957; AGFI = 0.841; CFI = 0.962; RMSEA = 0.155; SRMR = 0.031 | ||||

| Note: *** and ** indicate statistical significance at 0.01 and 0.05 levels, respectively (2-tailed) | ||||

References

- Majumdar, A.; Shaw, M.; Sinha, S.K. COVID-19 debunks the myth of socially sustainable supply chain: A case of the clothing industry in South Asian countries. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N. Do board sustainability committees contribute to corporate environmental and social performance? The mediating role of corporate social responsibility strategy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Jin, S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability: From a Corporate Governance Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emran, M.S.; Islam, A.; Shilpi, F. Distributional Effects of Corruption When Enforcement is Biased: Theory and Evidence from Bribery in Schools in Bangladesh. Economica 2020, 87, 985–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Zarkada, A.; Ramayah, T. The impact of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control on managers’ intentions to behave ethically. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasser, Q.R.; Al Mamun, A.; Ahmed, I. Corporate social responsibility and gender diversity: Insights from Asia Pacific. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International Corruption Perception Index. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2022 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- TBS Report. It’s Corruption that Bites Business Harder: CPD. 2023. Available online: https://www.tbsnews.net/economy/corruption-remains-most-problematic-factor-doing-business-cpd-575938 (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- TRACE Bribery Risk Matrix. Available online: https://www.traceinternational.org/trace-matrix (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Barakat, F.S.; Pérez MV, L.; Ariza, L.R. Corporate social responsibility disclosure (CSRD) determinants of listed companies in Palestine (PXE) and Jordan (ASE). Rev. Manag. Sci. 2015, 9, 681–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, F.; Baird, K.; Munir, R. The association between organisational culture, CSR practices and organisational performance in an emerging economy. Meditari Account. Res. 2020, 28, 977–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, F.; Knirsch, M. Responsible leadership and corporate social responsibility: Metrics for sustainable performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, S.R.; Zamanou, S.; Hacker, K. Measuring and interpreting organizational culture. Manag. Commun. Q. 1987, 1, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G.G.; DiTomoso, N. Predicting corporate performance from organizational culture. J. Manag. Stud. 1992, 29, 783–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, C.A.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Auditor independence decision making: The role of organizational culture perceptions. Behav. Res. Account. 1996, 8, 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, I.C.; Branco, M.C.; Curto, J.D.; Eugénio, T. How does the market value corporate sustainability performance? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J.A.; Caldwell, D.F. People and Organizational Culture: A Profile Comparison Approach to Assessing Person-Organization Fit. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaqtari, F.; Elsheikh, T.; Tawfik, O.I.; Youssef, M.A.E.A. Exploring the Impact of Sustainability, Board Characteristics, and Firm-Specifics on Firm Value: A Comparative Study of the United Kingdom and Turkey. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletic, M.; Maletic, D.; Dahlgaard, J.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.M.; Gomišcek, B. Do corporate sustainability practices enhance organizational economic performance? Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2015, 7, 184–200. [Google Scholar]

- Veselovská, L.; Závadský, J.; Závadská, Z. Mitigating bribery risks to strengthen the corporate social responsibility in accordance with the ISO 37001. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1972–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Scott, T.; Davies, H.T.; Bower, P.; Whalley, D.; McNally, R.; Mannion, R. Instruments for the Exploration of Organisational Culture–Compendium of Instruments; School of Management, University of St Andrews: St Andrews, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wijethilake, C.; Upadhaya, B.; Lama, T. The role of organisational culture in organisational change towards sustainability: Evidence from the garment manufacturing industry. Prod. Plan. Control. 2021, 34, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, K.; Hu, K.J.; Reeve, R. The relationships between organizational culture, total quality management practices and operational performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2011, 31, 789–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanak HS, H.; Said, R.M.; Abdullah, A.; Daud, Z.M.; Abu-Alhaija, A.S. Corporate Organizational Culture and Corporate Social Responsibility Activities: An Empirical Evidence from Jordan and Palestine. Int. J. Bus. Econ. 2020, 2, 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Xenikou, A.; Furnham, A. A correlational and factor analytic study of four questionnaire measures of organizational culture. Hum. Relat. 1996, 49, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Judge, T.A.; Vohra, N. Organizational Behavior, 15th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Coming to a new awareness of organizational culture. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1984, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.; Dowell, G. A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L.; Milstein, M.B. Creating sustainable value. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2003, 17, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I.; Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and measuring corporate sustainability: Are we there yet? Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M. Theorizing firm adoption of sustaincentrism. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, L. Corporate social responsibility research in accounting. J. Account. Lit. 2015, 34, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Luft, J.; Shields, M.D. Subjectivity in developing and validating causal explanations in positivist accounting research. Account. Organ. Soc. 2014, 39, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.; Serafeim, G. An analysis of firms’ self-reported anticorruption efforts. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Lisic, L.L.; Zhang, I.X. Commitment to social good and insider trading. J. Account. Econ. 2014, 57, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurti, C.; Shams, S.; Velayutham, E. Corporate social responsibility and corruption risk: A global perspective. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2018, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, W.M.T.W.; Ahmad, N.N.; Ariff, A.M. Combating corruption for sustainable public services in Malaysia: Smart governance matrix and corruption risk assessment. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2018, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rettab, B.; Brik, A.B.; Mellahi, K. A study of management perceptions of the impact of corporate social responsibility on organisational performance in emerging economies: The case of Dubai. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntosh, E.W.; Doherty, A. The influence of organizational culture on job satisfaction and intention to leave. Sport Manag. Rev. 2010, 13, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Baird, K.; Blair, B. Employee organizational commitment: The influence of cultural and organizational factors in the Australian manufacturing industry. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 2494–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, K.; Harrison, G.; Reeve, R. The culture of Australian organizations and its relation with strategy. Int. J. Bus. Stud. A Publ. Fac. Bus. Adm. Ed. Cowan Univ. 2007, 15, 15–41. [Google Scholar]

- Artiach, T.; Lee, D.; Nelson, D.; Walker, J. The determinants of corporate sustainability performance. Account. Financ. 2010, 50, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Source Information Services. D&B Hoovers Database. 2016. Available online: https://app.avention.com/ (accessed on 20 October 2017).

- Boubakary, D.; Moskolaï, D.D. The influence of the implementation of CSR on business strategy: An empirical approach based on Cameroonian enterprise. Arab. Econ. Bus. J. 2016, 11, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, J.; DeHaan, E.; Rajgopal, S. Reputation repair after a serious restatement. Account. Rev. 2014, 89, 1329–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M.; Carstedt, G. Innovating our way to the next industrial revolution. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2001, 42, 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sarros, J.C.; Gray, J.; Densten, I.L. Leadership and its Impact on Organizational Culture. Int. J. Bus. Stud. 2002, 10, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioural research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A. Tailored Design Method: Encyclopaedia of Survey Research Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıç, M.; Gurler, H.E.; Kaya, A.; Lee, C.W. The Impact of Sustainability Performance on Financial Performance: Does Firm Size Matter? Evidence from Turkey and South Korea. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Griffiths, A. Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, R.A.; Straits, B.C. Approaches to Social Research, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gippel, J.; Smith, T.; Zhu, Y. Endogeneity in accounting and finance research: Natural experiments as a state-of-the-art solution. Abacus 2015, 51, 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Chow, C.W.; McKinnon, J.L.; Harrison, G.L. Organizational Culture: Association with Commitment, job Satisfaction, propensity to Remain, and information sharing in Taiwan. Int. J. Bus. Stud. 2003, 11, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).