Abstract

Controling river water pollution is one of the complex ecoenvironmental challenges facing China’s development today. The river chief information-sharing system (RCISS) in China is an institutional innovation carried out by the government to promote collaborative water governance in the era of big data. In order to explore the mechanism of the RCISS in China, this paper analyzed this system by establishing a theoretical analysis framework from the perspective of government data governance. Using this framework, this paper discussed the mechanism, institutional context and driving forces of the current river chief information-sharing system. Provincial-level practices of the RCISS were then analyzed in terms of information content, information transmission paths, intelligent platform and practice achievements, and finally the advantages and problems of the RCISS were summarized. The conclusions were drawn as follows: the river chief information-sharing system has huge advantages regarding the coordinated management of rivers, but there are problems regarding the imbalanced sharing of power among subjects and also disputes in terms of information security, fairness, authenticity and legality. This study provides insights into the operation of the RCISS and serves as a reference for other countries seeking a suitable solution to manage water environments.

1. Introduction

Regarding China’s watershed management, due to the unclear responsibilities and lack of detailed supporting regulations, the administrative law enforcement of watershed agencies is difficult to enact, and the ecological environmental problems of rivers and lakes are becoming increasingly prominent [1]. Water pollution control has remained subpar and is widely regarded as a major roadblock to the nation’s sustainable development [2]. The Chinese river chief system (RCS) is established as an innovative watershed collaborative governance approach to deal with the ecological environmental crisis in the river basin under the current legal system [3,4]. The RCS involves collaborations amongst the government, society and market sectors when it comes to the river-management process; the local leaders are the main parties responsible for river management, and the essence of RCS is to match the management of the water environment to the performance of the main leaders of the local party and government [1]. It originated from the Sanitation City Initiative in Changxing County, Zhejiang Province, in 2003 and was promoted by the Jiangsu Provincial government when conducting eutrophication control of Tai Lake in 2007. With the document titled “Regarding the Comprehensive Implementation of the River Chief System” issued by the central state in 2016, the RCS officially transferred from a local emergency policy to a national normalization policy. Until 2017, according to the statistics from the Ministry of Water Resources, there were 310,000 river chiefs at provincial, city, county and township levels, and almost 610,000 river chiefs at the village level. The RCS is considered to be a more effective method to gradually and sustainably improve China’s environmental conditions, particularly in water environments [2].

The major mission of the RCS is incorporating multistakeholders into the river management framework to effectively achieve the goals of pollution control, environmental improvement, resource conservation, ecological restoration and water security. Information sharing is a core part of the RCS [5], and it ensures that data and information on river protection and management are shared; additionally, this information is used to track the progress in the implementation of the RCS [6]. In 2017, the document “Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Development of Water Conservancy Big Data” was promulgated by the central Ministry of Water Resources, and it put forward that a platform of water information exchange between horizontal- and vertical-water resource departments should be established to ensure the information connectivity between water conservancy departments at all levels; additionally, a catalog of water conservancy information resources and the orderly provision of shared services should be promoted to ensure data sharing between departments [7].

Currently, the Chinese Ministry of Water Resources has integrated the existing water conservancy business information into a brand-new river chief system shared information database and set up functions to share information. This information-sharing system has made achievements in supporting river chiefs in fulfilling duties and assisting other related groups’ participation into water governance, which signaled a new stage in the promotion of the river chief system in China. This article provides a systematic exposition and analysis of this information-sharing system, in which we map the mechanism, institutional context, driving forces and practices of the river chief information-sharing system (RCISS) from the perspective of data governance.

The rest of the article is organized as follows: Section 2 briefly reviews the literature on information sharing, and in Section 3, a theoretical framework for the RCISS is presented. In this section, three dimensions of the framework are analyzed: the institutional context, motivations and information-sharing mechanism. Section 4 describes the RCISS practice in China through provincial-level practices in terms of information content, information transmission paths, intelligent platforms and practice achievements. Section 5 discusses the advantages and limitations of the RCISS, and Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Information plays an important role in social change [8] and gradually acts as the basic criterion for the operation of human society. As a key path to the full release of information and a prerequisite for realizing the government’s governance innovation, information sharing has become a global movement [9]. More government departments are participating in the implementation of information-sharing policies [10], and the public’s dependence on government information sharing is also increasing [11].

Existing studies have suggested that information sharing can encourage innovation in government services [8] and is essential for developing smart governance infrastructure [12]. Governments can realize significant benefits by participating in information-sharing programs with other branches of government, governments from different nations, corporations and nonprofit organizations [13]. The interaction of information not only contributes to overcoming the boundary limitation between different departments, but it also improves their decision-making capabilities [14]. Through the iterative cycle of open information [10], the government could enhance its ability to adapt to situations with high complexity and uncertainty [15]. For example, the Chinese government established a COVID-19 prevention information system to help the public cope with negative emotions and enhance the government’s capacity to manage social panic during the pandemic [16]. However, there are still limitations in the government information-sharing system, including administrative system obstacles and the risks of privacy disclosure. Scholars believed that the data gap caused by the difference in technical level and information asymmetry may exert a negative impact on both information-poor and the information-rich individuals [17]. The institutional condition remains another limitation for government information sharing. It is more challenging for governments to share information across regions. For example, EU countries had strong disagreements on how public organizations share data with other public institutions or private organizations [18].

The governance of information sharing was divided into two types by Chinese scholars: “governance of data” [19] and “governance by data” [20,21]. In “governance of data”, the term “data” refers to the flow of data [19]. Huang’s study emphasizes that the need for data governance is evident in light of the sudden shift in the nature of data mobility from local and regional flows to free flows on a global scale [19]. Current studies focus on the instructive governance framework [22,23] and the regulation of cross-border data flows [24,25]. “Governance by data”, on the other hand, refers to the big-data-driven government capacity [21]. In promoting the government’s big data construction, scholars mainly focus on data opening [26,27], data applications [28], data management [29] and factors [30,31] that influence the government’s big data capability. From the perspective that the Internet has made the social governance model shift from a single center to a multicenter, scholars have proposed a concept of data governance under a multiple-collaborative governance system [32]. Here, the role of the government is inclined to be the coordinator between multiple social governance subjects. The government relies on its power to integrate the information from all governance subjects into a comprehensive data system [33]. Specifically, the central power can turn the will of the country into a realistic policy, while the local power can facilitate the achievement of national goals by offering various infrastructure and logistical technologies [34].

The RCISS in China, as a typical case of government data governance, has acquired the concerns of Chinese academics. The existing research primarily examines the technical supports of the information-sharing system of the RCS in various regions of China, such as the information collaborative office system of the RCS in Hunan Province [35] and the Wuxi river chief system integrated-information platform based on the blockchain storage system [36]. These studies argued that the information-sharing system provided technical support for river and lake governance, opened up social supervision channels [37] and comprehensively improved the efficiency of data exchange and the implementation of management strategies [36]. However, a systematic analysis of information sharing in the RCISS is rarely conducted from the perspective of data governance.

Therefore, in the context of data governance, this paper answers the following two questions: What is the theoretical foundation of the RCISS in China? How is the RCISS operated in China? Based on these questions, this paper analyzes three aspects of the RCISS: institutional context, driving forces and information-sharing mechanism. Then, the cases at the provincial level will be used to explore the success and problems of the RCISS in practice. The analysis is expected to be a reference for the improvement in the RCISS and also to provide other countries and regions with experience in building information-sharing systems about river governance.

3. Methodology

This research adopted a literature research method and case analysis method as the main methods. The literature included studies on the data governance and information sharing of governments and the implementation of the RCS in China and abroad. This is mainly discussed in Section 2, where the research in this area is presented in more detail, and we also refer to these references in subsequent chapters. The theoretical framework of the RCISS is established mainly based on the collaborative governance theory [38,39,40,41] and other studies such as [5,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. In addition to the scientific literature, the RCISS is also analyzed and summarized through provincial practice, and this is discussed in Section 4. We selected Beijing and the Yangtze River Delta as typical cases and discuss their achievements. The case analysis is based on official documents and news reports relevant to the RCISS through Baidu Web [49,50], outcomes of “Research and Training Center for River Chief System in Hohai University” such as [51] and studies conducted by Tang et al. [52] and Shen et al. [45], and we also refer to these references in corresponding sections. Through these means, we summarized the advantages and weaknesses of the RCISS. Possible solutions to solve problems have been proposed and discussed.

4. Analysis Framework of RCISS

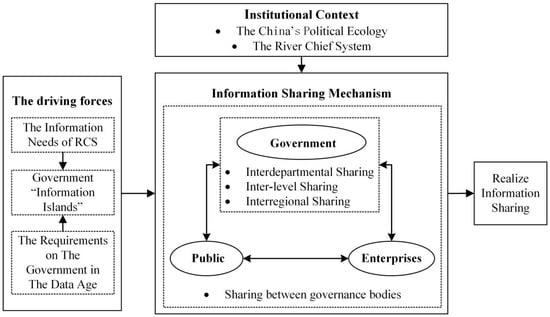

In the era of big data, data resources obtained from different subjects in the public management process have become a kind of important public good. Governments tend to manage and utilize these information resources to effectively perform their governance function in terms of social public affairs, which is called data governance [19]. The RCISS is a form of data governance, and its core is the collaborative governance mechanism between these different subjects, including the government, the market and society. According to collaborative governance theory, the collaborative governance mechanism is affected by external conditions [38], including institutional leadership [39], system context [40], driving forces [38], stakeholders [41], etc. Based on the above analysis and previous studies, this paper constructed an analysis framework for the RCISS (shown in Figure 1). This framework consists of two parts: the core system and the external condition. The external condition includes two aspects, the institutional context and driving forces, while the core system composes three subsystems, namely the government, the public and the enterprise system. This framework will be discussed in detail in the following paragraphs.

Figure 1.

The theoretical analysis framework of RCISS.

4.1. External Context of Information Sharing

4.1.1. Institutional Context

The institutional context of the RCISS consists of two dimensions, China’s political ecology and the river chief system, which could push or hinder the shape of the information-sharing system. China’s political ecology has the significant feature of the “whole of nation system” in which all levels of government and departments can establish a highly coordinated system to improve their level of supervision and mutual support. Specifically, the party–state hierarchy [42] and the centralized political authority [43] are the major elements of China’s political ecology. The centralized political authority shapes a governance system with a stronger top–bottom institutional administrative ability, which facilitates the cooperation between the departments involved in information sharing. Additionally, the people-oriented ruling philosophy of China’s ruling party also provides a good environment for the public’s participation in information sharing. In terms of the river chief system, it attempts to provide a platform for multiactors’ collaborative governance to overcome the boundary barriers between departments, levels, regions and stakeholders [44]. Therefore, its practice could be another important path foundation and institutional context for establishing an information-sharing system.

4.1.2. Driving Forces

Except for the institutional context, the driving forces, including the information needs of the RCS [45], the demand of the intelligent government in the data age [5] and the obstacle of interdepartmental “information islands” [46], also promote the establishment of the river chief information-sharing system.

- 1.

- The information needs of the river chief system.

One important function of the river chief system is to promote the cross-departmental, cross-level and cross-regional coordination of relevant water governance departments [44]. When sharing management information with the public, they could be involved as a supervisor, whereby they realize the cooperation between the government, civil society and the market sectors [38]. Therefore, there is a huge demand for timely, low-cost and large-capacity information resources shared by different subjects, which in turn acts as a force for information sharing.

- 2.

- The demand of the intelligent government in the data age.

In the context of big data, river management and decision-making processes are gradually shifting from a linear paradigm based on management processes to a flat interactive paradigm centered on data. The roles of related participants and the information flow have also been more diverse and interactive [5]. Therefore, to adapt to the transformation in the data age, the government should establish a completely new river governance system and take information sharing as the key path to achieve collaborative governance involving the government, enterprises and the public.

- 3.

- Obstacle from departmental “information islands”.

The traditional river management model follows a strictly centralized organizational form that emphasizes divisional management, power stratification and position grading [47]. It results in information barriers between horizontal departments and the issue of information selective reporting by lower-level departments with concerns about performance appraisal [48]. This phenomenon called “information islands” ultimately causes severe information fragmentation among various departments and hinders river governance, which in turn forces the establishment of the information-sharing system.

4.2. The Core System of Information Sharing

Based on the analysis of the institutional context and driving forces, this part would focus on the discussion about information-sharing mechanisms among stakeholders. The analysis framework divides the major participants into three groups, including the government, the public and the enterprise. The government is responsible for managing and supplying information resources, software and hardware facilities while enjoying the support that the data bring to their decision-making and management processes. The public provides information on water governance and supervision while obtaining access to the water environmental information relevant to their interests. The enterprise provides governments with resource utilization information and technical support to acquire river management project information and dynamic information on water resources. More details of the core system mechanism are as follows:

The information resources of the RCS are public goods, and there are higher requirements for information collection, storage, processing and security, so the shared information primarily relies on the supply of the government. Therefore, within the government subsystem, information-sharing mechanisms should be established among the departments, levels and regions in the same basin to overcome the barriers caused by the cross-departmental missions, the top-down performance appraisal system and the across-regional watershed. Attention should also be paid to the information exchange between the government subsystem and the other two subsystems to enhance the participation and support of the public and the enterprise.

The public can be divided into two types: the nongovernmental river chief and the general public. The nongovernmental river chiefs fulfill their duties of sharing river-inspection information with the government and enterprises promptly while improving their efficiency and ability by accomplishing tasks and obtaining learning resources. The general public can offer its supervision information to the government and the enterprise and simultaneously obtain information about the water environment to improve their quality of life.

There are two types of enterprises: The first one is the river-resources-consumed enterprise, which should disclose information on their resources-utilization process to obtain dynamic services information about river resources. The other one is the governance-supported enterprise. For example, the technical support enterprises develop information products based on information shared by other entities; the financial support enterprises provide information on the selection and operation of Public–Private Partnerships (PPP) projects related to river management.

5. RCISS Practice in China

In China, the RCISS is primarily practiced at the provincial level. A three-dimensional and intelligent information-management system would be established according to the work plan of the RCS. In order to clearly present the practice of the RCISS in China, this part will analyze the content and transmission path of shared information, as well as the structure, functions, operation mechanism and typical achievements of the sharing platform.

5.1. The Content of the Shared Information

Under the current organization system of the RCS, the contents of shared information are primarily concluded in the following categories.

- 1.

- Basic information.

Basic information could be divided as follows: First, remote-sensing image maps of administrative boundaries, traffic and water systems at all levels. Second, the river chief publicity sign that reflects the river chief’s responsibilities, river and lake overview, management and protection goals, supervision channels and other information. Third, the information about the river chief, including the classification and corresponding responsibilities. Fourth, management information on water conservancy projects, including information about hydrology and water conservancy facilities. Fifth, the river reach management information, including the name and corresponding code of the river reach, hydrological information, the administrative area that the river flows through, the river management level, etc.

- 2.

- Professional information.

Professional information refers to the information related to river management, which includes the following: First, the shoreline management information of rivers or lakes, such as the delineation of the shoreline space and the functional zones, the development and protection of the shoreline, etc. Second, water resources management information, such as inflow into the rivers or lakes, water supply and consumption status, etc. Third, information on water environment management, such as the discharge of major pollutants, the protection status of the drinking water source, etc. Fourth, water ecological restoration management information, such as information on soil erosion and water conservation.

- 3.

- Management information.

Management information refers to the information related to river management activities. Specifically, it can be concluded as follows: First, information on the supervision and enforcement, such as the enforcement and supervision of the relevant laws, punishment and rectification of illegal acts, etc. Second, performance appraisal information, such as the river chief patrol records. Third, river problems reported by river chiefs, the public and enterprises, and the solutions to these problems. Fourth, policy information including the latest policies on river management. Fifth, experiences including the successful and failed cases of river management. See Appendix A for details.

5.2. Information Transmission and Sharing Paths

In order to clarify the transmission and sharing paths of RCS-related information, for this part, we conducted further path analyses in terms of basic information, management information and professional information.

- 1.

- Basic information.

Basic information is primarily the business data of the public sector, which are currently provided by the government. The government departments, including the water resources department, the ecological and environment department, the natural resources department, the agriculture and rural department, etc., share their information and form a database with their shared information. With the database, integrated information is furtherly transferred and shared by these departments with other participants in the RCS, such as river chiefs, the public and enterprises. Therefore, the analysis of basic information transmission and sharing paths would be carried out firstly within the government subsystem (excluding the river chief) and then among different subsystems. The specific path is as follows:

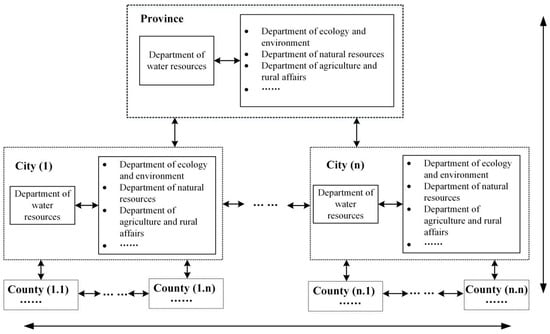

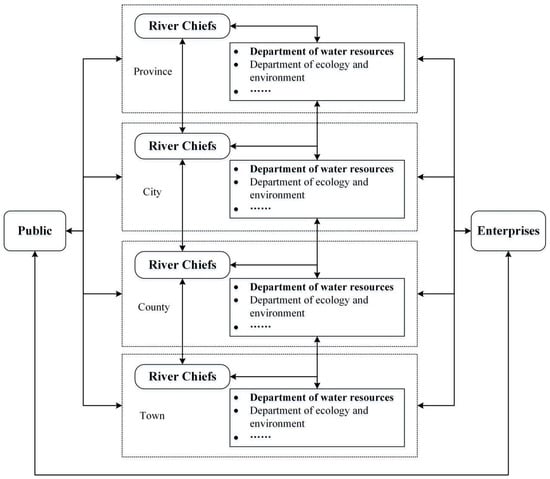

In the government subsystem of the RCS, the basic information is transmitted and shared in the horizontal and vertical dimensions (see Figure 2). Horizontally, basic information is primarily transmitted within and between administrative areas. In the administrative area, government departments such as the ecological environment department, the natural resources department and the agriculture and rural department transfer the basic information related to river governance to the water resources department. After obtaining the information, these departments form a basic information database and offer information according to the needs of different departments in the administrative area. Among the administrative areas, basic information is transferred from one database to another database. Vertically, the basic information transmission and sharing among governments at the four levels of provinces, cities, counties and towns can be realized through mutual access between different levels’ basic databases.

Figure 2.

Basic information transmission and sharing in the government subsystem.

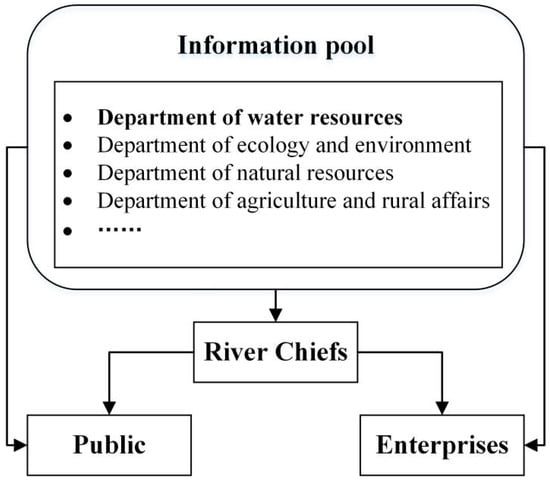

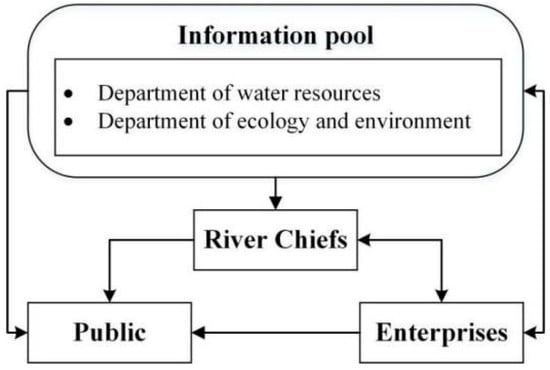

On the basis of linking basic information databases in all levels of the government subsystem, a basic information pool is formed to connect with other subsystems. Basic information is primarily transmitted and shared between different subsystems through the following two paths (Figure 3): The first path is that the government departments grant the public and enterprises access to the basic information pool and allow them to directly obtain the information. The second path is that river chiefs at all levels can access the database and provide information to users of the other two subsystems in accordance with the needs of the river governance.

Figure 3.

Basic information transmission and sharing among subsystems.

- 2.

- Professional information.

Professional information includes information related to river basin management and protection. Currently, most professional information is offered by public sectors, including the water conservancy departments and environment departments, while a small amount of information is provided by enterprises in the form of the government’s purchase services. Therefore, the first step is to analyze the professional information transmission and sharing in the government subsystem (excluding the river chief), followed by the analysis of information transmission and sharing among different subsystems. The specific path is as follows:

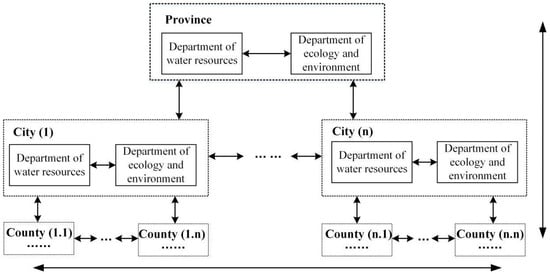

Similar to basic information transmission and sharing paths, the transmission and sharing paths of professional information also have two dimensions: the horizontal and vertical dimensions (Figure 4). From a horizontal perspective, professional information is transmitted and shared within and among administrative areas. In the administrative area, water resources departments primarily provide river shoreline management information, water resources management information and a small amount of water environment management information and ecological restoration management information. The ecology and environment departments provide supplementary information on water environment management and water ecological restoration management, such as the amount of pollutants entering the river, information on the sewage outlets, the status of the ecological space, etc. All the professional information is used to construct the regional professional information database. Among the administrative areas, professional data can be transmitted and shared so that there is mutual access to different regional professional information databases.

Figure 4.

Professional information transmission and sharing in the government subsystem.

From a vertical perspective, professional information transmission is realized through the linkage between the upper and lower professional information databases. From bottom to top, there are two types of information transmission paths: the superiors directly access the information database of the subordinates, or the superior requires subordinates to report professional information through the information transmission channel according to their needs. From top to bottom, the professional information is also transmitted through two paths: the superior directly transmits the information to the subordinate, or the subordinate applies for access to the superior database according to their demands. With the horizontal and vertical multitransmission paths, professional information can be transmitted and shared among four levels of government: province–city–county–township. On the basis of linking professional information databases in all levels of the government subsystems, a professional information pool is formed and connected with other subsystems (Figure 5). The information among subsystems is transmitted through three paths. The first path is “information pool-river chief-the public”. River chiefs obtain professional information by visiting the information pool and then directly provide the public with information according to their management needs. The information pool can be opened directly to the public and provides the information that they required (the public here includes the general public and the nongovernmental river chiefs). The second path is “information pool-river chief-the enterprise”. River chiefs can access professional information from the database and pass the information to the enterprises according to management requirements. Or, the enterprises can obtain the information due to the open access of the database. At the same time, these enterprises supporting the river governance in turn transmit their professional information to the information pool. The third path is “river chief-the public-the enterprise”. River chiefs transmit professional information to the public and enterprises because they perform their duties. As for the enterprises, the river-resource-consuming enterprises disclose professional information such as water withdrawals and pollution discharge, while the river-governance-serving enterprises provide support to the river chiefs and the public by opening their professional information.

Figure 5.

Professional information transmission and sharing among subsystems.

- 3.

- Management information.

Management information is the information generated by all participants in river governance. Here, the major subjects primarily include river chiefs, river chief system administrative departments, the public and enterprises. The specific paths for management information transmission and sharing are shown in Figure 6. In the government subsystem, the management information is transmitted with river chiefs as the core. At the same level, government departments (such as water conservancy departments and environmental departments, etc.) pass their management information to river chiefs, while river chiefs in turn provide obtained information to the relevant departments. Between the different levels, routine management information (such as information on supervision and law enforcement, river patrol records, etc.) is reported by the river chief department to its higher-level river chief department or delivered to the lower-level one. Similarly, special management information (such as the river chief tasks, the latest policies, the needs of the river chiefs, etc.) is also transmitted between the upper and lower levels by the river chiefs.

Figure 6.

Transmission and sharing paths of river chief management information.

In the public subsystem, as for the general public, if they find problems in the river governance (such as excessive river discharge, illegal water withdrawal, etc.) or negligence of the river chiefs and governmental departments, they can report these problems to the river chiefs and river chief system authorities at all levels. Meanwhile, river chiefs and river chief system authorities at all levels should deal with these problems and give timely feedback. Another type of public subsystem is nongovernmental river chiefs selected by the general public; they report the performance of their duties to their superiors and receive information about their tasks.

In the enterprise subsystem, river-resource-consuming enterprises disclose information regarding the utilization of river resources (such as water withdraws, sewage discharge into the river, river sand mining, etc.) to river chiefs and river chief administrative departments at all levels and the public, whereas the enterprises obtain dynamic information (such as changes in water resources, river navigation situation, etc.) from water conservancy departments and environmental departments. River-governance-serving enterprises deliver service information related to river governance to river chiefs and river chief departments at all levels and to the public. At the same time, these enterprises obtain information that supports decision-making processes from river chiefs and river chief system authorities at all levels and the public.

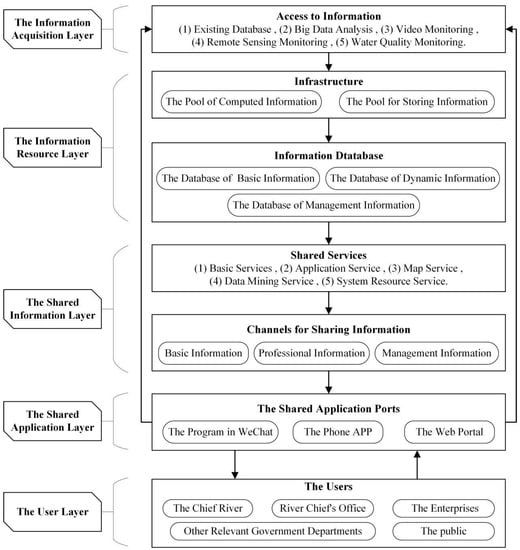

5.3. Structure and Operation of RCISS Intelligent Platform

The intelligent platform is an important place for the operation of the RCISS. Currently, the RCISS intelligent platform generally consists of five layers, which are the information-acquisition layer, information-resources layer, information-sharing layer, information-application layer and information-user layer [51], as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The intelligent platform of RCISS [51].

- The information-acquisition layer links to the existing river and lake information database and is used to conduct the cleaning and preliminary analysis of the obtained data.

- With the information-resource layer, the standardized calculation and storage procedures of the input information are executed, and the information is accurately classified to form a shared information database that includes a basic information database, a dynamic information database and a management information database.

- The shared information layer provides information-sharing services that include basic information sharing, data-mining services, etc. It also forms a shared information channel that includes a basic information channel, a professional information channel and a management information channel.

- The shared application layer is an interactive window for information sharing with three application ports: the WeChat application, mobile phone apps and Web portal.

- The user layer is primarily open for all the users involved in the RCS, including river chiefs at all levels, river chief offices at all levels, river chief cooperative units, related enterprises and the public.

The five layers composing the RCISS form an information-sharing closed loop of “acquisition-processing-sharing-feedback” (Figure 7). The specific operation mechanism can be decomposed as follows: Firstly, with the information-acquisition layer, data are acquired by accessing the interface of the relevant government department information database, using big data technology to mine the Internet information or directly adopting real-time monitoring technology. Then, the obtained information is transmitted to the information-resource layer and is used to form the information resources reserve through the procedures of identification, classification, processing and standardization. Secondly, by linking the information-resource layer to the shared information layer, the processed information would be transmitted to the shared information layer and provided to users according to their needs. The third step is to form the information-sharing channel and the information-feedback channel. Three channels of basic information, professional information and management information are established through the linkage between the shared information layer and the shared application layer, while the user information feedback channel is formed by connecting the application layer and the information-acquisition layer (e.g., the application includes the independent applications such as a dedicated application or website, as well as an application embedded in other applications such as the WeChat application). Finally, users can access the information through the application window and share their information through the feedback channel. Through the information-sharing system, the government, the public and enterprises can realize the circular flow of information via “sharing-feedback-sharing”. Information sharing has been realized among the government, the public and enterprises.

5.4. Typical Achievements

5.4.1. RCISS in Beijing

The RCISS in Beijing is a typical case of realizing the data interaction of the multiple-services platforms of the river chief system. It succeeds in providing information resources to implement the RCS via information exchange among the platform of big data analysis and display, the platform of information collecting, the river chief system information platform of the Ministry of Water Resources and the district-level river chief system platform. The functions of river management include:

- Water resource conservation. The information-sharing system provides government departments, water consumption enterprises and the public with real-time information on water resource protection. It realizes the maintenance, publication, browsing and inquiry of water resource protection information and interaction among multiusers.

- Shoreline management of the river. The system makes it possible to share information on the whole management process of the demarcation of shoreline waters and real-time information on mobile inspection and automatic monitoring.

- Water pollution prevention and control. The pollution monitoring system locks the number and location of pollution sources and transmits it to the information processing center to generate evaluation information, which is then shared with various management departments.

- Water environmental management and ecological restoration. The information-sharing system can conduct differentiated data processing and analysis on water environment monitoring information, water environment simulation and analysis information, water environment remote-sensing evaluation information and water quality warning information and share the results with relevant departments.

- Strengthening law enforcement and supervision. The information such as team information on water administration supervision, water dispute warning information, water administrative permit project real-time monitoring information, water administrative penalty real-time monitoring information, etc. is shared in this system to strengthen the enforcement and supervision.

According to the statistics, there are approximately 12,000 end users of the Beijing river chief information-sharing system, and about 2500 users were online every day until 2020. These users include third-party inspectors and river chiefs in cities, districts, towns (streets) and villages. As of February 2020, based on the terminal application of the Beijing river chief information-sharing system, 350,000 river patrols have been carried out. The total length of the patrols exceeded 1.2 million km, and more than 2000 problems were reported [52].

5.4.2. The Transregional Joint River Chief Information-Sharing System in the Yangtze River Delta

Currently, the transregional joint river chief information-sharing system in the Yangtze River Delta is in its pilot stage. The regions covered by the joint information system include Qingpu District in Shanghai; Wujiang District in Suzhou City, Jiangsu Province; and Jiashan county in Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province. There are about 46 transboundary rivers in the 2300 km2 area covered by the system. The information-sharing service is primarily for the joint river chiefs at all levels of the three prefectures, the office of the river chief system at all levels, and the relevant member units of the river chief system, such as the departments of water conservancy, water affairs, agriculture and rural areas, ecological environment, transportation and other departments [45]. With the help of the joint river chief information-sharing system, transboundary water quality monitoring sections have shown a significant improvement trend [53].

The major function of the information-sharing system is to share river governance information, including information on the progress of bordering river governance; interpretations of the latest water ecological environment policy; typical cases; and experiences in terms of river management ideas, technologies and approaches. Specifically, the system function can be subdivided into the following five aspects:

- The river information database is used to collect and process basic information about rivers, which supports various governance entities to formulate working plans.

- The river chief performance platform is used to record and share the performance of river chiefs at all levels, feedback problems and corresponding handling methods and the progress of governance work.

- The problem-handling platform is responsible for coping with the problems discovered by river chiefs at all levels or those reported by the public. For example, the public can upload photos, videos, problem locations, problem types and other related information about water issues to the platform through WeChat and then leave a contact number for follow-up feedback.

- The river-water-quality information-sharing platform can be used for water quality data statistics and a water quality analogy judgment. Once verified by the water quality inspection unit, the water quality data of the border river can be regularly publicized on this platform. The river chiefs at all levels can check the water quality of the river they are responsible for on the river chief app.

- The online information-exchange platform can be used for internal quick contacts and document transfers.

6. Discussion

From the above analysis, it can be seen that the RCISS practices in many provinces have shown the important advantages of the system in water governance. However, similar to other government information-sharing systems, this system has problems in both theory and practice. This section will discuss the advantages and problems of the RCISS.

The RCISS has some advantages in the following aspects: (1) It reduces the time and cost of acquiring information on river and lake management and unifies the information caliber. By changing the previous way river management departments used to independently obtain information, the issue of information fragmentation can be solved, and the credibility and validity of the information can also be improved. (2) It enriches the related information sources and improves the timeliness of the required information, which provides solid scientific support to river management. The RCISS is a self-learning and self-renewal system. Combining big data technology, real-time monitoring technology and the users’ feedback mechanism, this system is expected to expand the information supply channel and shorten the time of information transmission. Therefore, it can effectively improve the speed at which relevant departments respond to problems and can then provide a scientific basis for decision making. (3) It promotes the re-engineering mechanism of river and lake governance. The information-sharing system changed the original information basis of river and lake governance, which prompted the adjustment of the river and lake governance system. In particular, the multisectoral cooperation and the participation of enterprises, social organizations and the public in the governance of the river improved.

However, there are problems and controversies with the information-sharing system, which mainly reflect the following two aspects. In one aspect, the driving forces of the RCISS obviously differ among subjects. Because information resources are public goods, the public sector becomes the main force for information sharing. Although the enterprises and the public are engaged in information-sharing systems, the level of their forces is significantly lower than that of the government. As profit-oriented organizations, enterprises have an insufficient incentive for information sharing due to concerns about the vague property right of information resources. As for the social public, their participation ability and consciousness limit their force in sharing information.

In another aspect, the current information-sharing systems in the RCS are controversial in terms of security, fairness, authenticity and legality. (1) All information is stored in one system regardless of its importance level, which leads to increased information security risks. For example, information leakage or system operation failure would cause greater losses once it happens. (2) Although the system sets up different sharing levels for users to ensure information security, it has created another issue of fairness. In particular, with no clear legal definition of the correct way to use information, the unfair phenomenon of “winners dominate” in information-sharing systems is more likely to occur. (3) Furthermore, the authenticity of the shared information in this system, especially the public feedback information, is insufficient, which may cause misjudgments in river management. (4) The current system is also controversial regarding the legitimacy of the information-acquisition methods and channels, as well as the legitimacy of the purpose and scope of the information use. Both will have an important direct impact on the effectiveness of supervision and law enforcement. In conclusion, the RCISS has improved the capacity of river and lake governance in China, but it should be improved in two aspects: the diversification of the information-sharing forces and the optimization of the sharing mechanism. In view of this, some advice is proposed. First of all, it is suggested to clearly define the boundary between the government and the market to take full advantage of the market in driving information sharing. Meanwhile, the government should cultivate the public’s awareness and ability to participate in information-sharing process and establish a multidriver mechanism with the enterprises and the public working together. Secondly, advanced technologies such as blockchain technology can be used to optimize the information-sharing system to improve the security and authenticity of information. Thirdly, an incentive and penalty system for information sharing should be established to promote collaborative river management. Finally, improving the legal system of the RCISS, clearly defining the property rights of the information resources, and enhancing the fairness and legitimacy of the existing system are suggested to ensure the sustainable operation of the information-sharing system.

This study has some limitations. This study established a theoretical framework of the RCISS and discussed and summarized the RCISS practices in China under this framework; the RCISS expands our knowledge of the diversity of water management tool choices, which provides insights that may be useful to other developing countries seeking to establish an information-sharing system in water management. However, the empirical analysis is a weakness of this study. This study failed to give an exact solution to the weaknesses of the RCISS. For example, we were unable to determine how to improve the driving forces of the enterprises and the public in the RCISS, or more exactly, the influencing factors of the participation of the enterprises and the public, which thus leads to a multidriver mechanism with the enterprises and the public working together. Wu et al. [48] conducted an effective review of the innovative models of public participation and also proposed to further enhance the capacity for public participation. How to improve the legal system of the RCISS is another problem. Zhang [54] believes that there are two main modes of legislation on the RCS: one is special legislation on the RCS and the other is the inclusion of the RCS in other legislation, and both have their advantages and disadvantages and are used in practice. Zhang gives solutions to related difficult issues such as the reasonable determination of the legislative hierarchy of the RCS. However, this study does not provide a clear definition of the property rights of information resources. Although this study summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of the RCISS in terms of the system itself, research on the above content is meaningful.

7. Conclusions

The improvement in China’s water environment not only demonstrates effective water pollution management but also creates opportunities for sustainable economic and social development. Such progress would not have been possible without institutional innovation in water pollution governance [55]. The river chief information-sharing system is an institutional innovation carried out by the Chinese government to promote the collaborative governance of rivers in the era of big data. However, the existing studies primarily focus on discussing its technical level rather than conducting a theoretical analysis. Thus, from the perspective of government data governance, this paper establishes a theoretical analysis framework of the river chief information-sharing system in China. In this framework, in the context of China’s political ecology and the river chief system, the river chief information-sharing system primarily includes three types of subjects consisting of the government, the public and enterprises, and is driven by the information demand of the river chief system, intelligent government and “information island”. Since its launch in 2017, the river chief information-sharing system has been implemented at the provincial level and made notable achievements in Beijing and the Yangtze River Delta region.

Our analysis found that the river chief information-sharing system brought about cost reduction and efficiency improvement in information sharing and promoted the reconstruction of the government’s river governance system. And in this system, the government takes information sharing as the key path to achieve collaborative governance involving the government, enterprises and the public. The government is responsible for managing and providing information resources while also receiving data support for decision-making and management processes. However, there are still problems and controversies with this system, such as the simplicity of government-led driving and the limitations in terms of information security, fairness, authenticity and legitimacy. Therefore, some suggestions were given in this paper in terms of defining the boundary between the government and market, cultivating public participation consciousness and ability, applying new technology and perfecting the relevant legal system. The river chief information-sharing system in China, as a typical example of a government data-sharing system embedded in a river and lake governance system, is expected to provide a reference for other regions and countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z.; funding acquisition, D.S.; methodology, X.Z., W.W. and W.Y.; project administration, D.S.; supervision, D.S.; visualization, X.Z. and T.Z.; writing—original draft, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.W., W.Y., D.S. and T.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Information content of RCISS in China.

Table A1.

Information content of RCISS in China.

| Basic Information | Professional Information | Management Information | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic information |

| Riparian line management information |

| Information on supervision andenforcement |

|

| RCS public board information |

| Water resources management information |

| Information on performance reviews |

|

| River chief information |

| Water environmental management information |

| Information on river problems and feedback |

|

| Project management information |

| Water ecological restoration management information |

| Information on policies |

|

| River management information |

| Information on experience |

| ||

References

- Tang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jiao, J. Ecological security assessment of Chaohu Lake Basin of China in the context of River Chief System reform. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 2773–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, J.; Zhang, K.; Wen, B.; Lu, Y. Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches to Environmental Governance in China: Evidence from the River Chief System (RCS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Wan, J.; Zhu, Y. River chief system: An institutional analysis to address watershed governance in China. Water Policy 2021, 23, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tong, J.; Wang, L. Full Implementation of the River Chief System in China: Outcome and Weakness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.H.; Yu, F.X.; Guan, L.N. Government governance innovation in the data era based on the perspective of data open sharing. E-Gov. 2020, 9, 74–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Richards, K. The He-Zhang (River chief/keeper) system: An innovation in China’s water governance and management. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2019, 17, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y. Advancing modernization of water conservation management with big data. Water Resour. Informatiz. 2017, 4, 6–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Jun, S.-P. Privacy-preserving data mining for open government data from heterogeneous sources. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K. Research on the reflection and reform of digital governance: Triple separation computing debate and governance fusion innovation. E-Gov. 2020, 5, 40–48. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.M.; Wu, Y.J. Looking for datasets to open: An exploration of government officials’ information behaviors in open data policy implementation. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csontos, B.; Heckl, I. Accessibility, usability, and security evaluation of Hungarian government websites. Univ. Access. Inf. Soc. 2021, 20, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.W.; Hansen, D.L. Design Lessons for Smart Governance Infrastructure. In Transforming American Governance: Rebooting the Public Square; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Garcia, J.R. Towards a smart State? Inter-agency collaboration, information integration, and beyond. Inf. Polity 2012, 17, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.M. Mega Data Governance:An Essential Approach to the Modernization of State Governance. J. Jishou Univ. 2015, 36, 34–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Z. Cooperative Society and Its Governance; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.Q.; Liu, J.W.; Yuan, Y.C.; Burns, K.S.; Lu, E.Z.; Li, D.X. Source Trust and COVID-19 Information Sharing: The Mediating Roles of Emotions and Beliefs About Sharing. Health Educ. Behav. 2021, 48, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, G.; Jacobsen, T.E.; Batcheller, A.L. Information asymmetry and information sharing. Gov. Inf. Q. 2007, 24, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otjacques, B.; Hitzelberger, P.; Feltz, F. Interoperability of E-Government Information Systems: Issues of Identification and Data Sharing. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 23, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Governance of “Flows of Data”: Theory Development and Framework of Government Data Governance. Nanjing J. Social. Sci. 2018, 2, 53–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Chen, L. Research on Government Big Data Capacity from Organizational Perspective. J. Public Adm. 2017, 10, 91–114, 207–208. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Meng, T.G.; Zhang, X.J. Big Data Driven and Government Capacity Building:Theoretical Framework and Innovative Models. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2018, 31, 18–25. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Xu, Y.; Wu, H.; Ma, J.; Gao, J. Sustainable Insights for Energy Big Data Governance in China: Full Life Cycle Curation from the Ecosystem Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G. Innovating and Reshaping the Data Governance System: Financial Data Governance as an Example. Bus. Manag. J. 2023, 45, 25–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaronson, S.A.; Leblond, P. Another Digital Divide: The Rise of Data Realms and its Implications for the WTO. J. Int. Econ. Law 2018, 21, 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Niu, M. Research on the Logical System of Regulating Global Cross-border Data Governance. Lib. Inf. 2023. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail//62.1026.G2.20221221.1250.001.html (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Lee, G.; Kwak, Y.H. An Open Government Maturity Model for social media-based public engagement. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Shanab, E.A. Reengineering the open government concept: An empirical support for a proposed model. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L. The value creation mechanism of open government data: An ecosystem perspective. E-Gov. 2015, 7, 2–7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N.; Ravindran, R.; Nicosia, S. Government data does not mean data governance: Lessons learned from a public sector application audit. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-M.; Wu, Y.-J. Examining the socio-technical determinants influencing government agencies’ open data publication: A study in Taiwan. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J.; Lo, J. Adoption of open government data among government agencies. Gov. Inf. Q. 2016, 33, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Xi, J.R. Study on Governance Innovation of Government in the Context of Big Data. J. Shanghai Adm. Inst. 2020, 21, 33–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.Z. On the Change of Government Behavior from Controlling Pattern into Guiding Pattern. J. Beijing Adm. Coll. 2012, 2, 22–29. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.X. State, War and Historical Development: A Comparison of Chinese and Western Models in Pre-Modern Times; Zhejiang University Press: Zhejiang, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.H.; Zhai, W.F.; Shi, L.; Peng, H.; Zhang, H.K. Thoughts and Prospects on Application of Management Information System of River (Lake) Chief System in Hunan Province. Hunan Hydro Power 2020, 3, 115–118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.P.; Lin, P.; Zhao, Y.N.; Xie, Z.P.; Liu, Y. Construction and thinking on integrated information platform of Wuxi River-leader System. Jiangsu Water Resour. 2020, 6, 25–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.L. Practice and consideration on construction of the river chief system information management system in Liaoning Province. Water Resour. Dev. Manag. 2020, 6, 80–84. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X. River chief system as a collaborative water governance approach in China. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2020, 36, 610–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxham, C.; Vangen, S. Managing to Collaborate: The Theory and Practice of Collaborative Advantage; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2011, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.L.; Bryer, T.A.; Meek, J.W. Citizen-Centered Collaborative Public Management. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartier, C. Territorial Urbanization and the Party-State in China. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2015, 3, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.F. Mandate Versus Championship: Vertical government intervention and diffusion of innovation in public services in authoritarian China. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M. The River-chief mechanism: A case study of China’s inter-departmental coordination for watershed treatment. J. Beijing Adm. Coll. 2015, 3, 25–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.W.; Jin, X.; Wang, Z. Brief introduction of information management system for implementing joint river chiefs in Yangtze River Delta demonstration area. China Water Resour. 2020, 20, 34–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, G.; Wen, S.J.; Zhao, J.J.; Chen, H. Integration and sharing of government data resources: Demand dilemma and key path. E-Gov. 2020, 10, 109–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H. History of Western Administrative Theory (Revised Edition); Wuhan University Press: Hubei, China, 2004. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.H.; Ju, M.S.; Wang, L.F.; Gu, X.Y.; Jiang, C.L. Public Participation of the River Chief System in China: Current Trends, Problems, and Perspectives. Water 2020, 12, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Li, L.-Z.; Huang, J.-K. The river chief system and agricultural non-point source water pollution control in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1382–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.R.; Jin, G. The Policy Effects of the Environmental Governance of Chinese Local Governments: A Study Based on the Progress of the River Chief System. Soc. Sci. China 2020, 41, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.S. River Chief System Policy and Organization; China WaterPower Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.; Yin, X.N.; Li, X. Application Design and Development of Smart Mobile Terminal of River Chief in Beijing. Yellow River 2020, 42, 164–168. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Z.; Hu, X.; Wu, Z.; Ji, Y.; Han, F.; Liu, Y.; Lu, X. Exploration and Practice of Long-term Mechanism for Transboundary River and Lake Management in the Yangtze River Delta Demonstration Area. Water Dev. Res. 2021, 21, 48–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Legislation of River Length System: Necessity, Mode and Difficulty. Hebei Law Sci. 2019, 3, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Shi, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, L. Trade-off between economic development and environmental governance in China: An analysis based on the effect of river chief system. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 60, 101403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).