Abstract

The senior tourist market is growing, because the number of elderly people is increasing in Korea. It is widely accepted that experience in travel is more important than any other factor. Thus, the aim of this study was to examine the importance of the experience economy and its impact on outcome variables with the moderating role of tour guiding services in the senior tourism industry. This study more specifically proposed that there is a positive relationship between the four dimensions of the experience economy, which include education, entertainment, aesthetics, and escapism, and tour quality. In addition, it was proposed that tour quality has a positive influence on tour satisfaction and word-of-mouth. Lastly, this study investigated the moderating role of a tour guide service in the relationship between the experience economy and tour quality. The data were collected from 323 seniors who had experienced an overseas package tour in Korea. In order to test the proposed model, this study employed confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling analysis. The data analysis results indicated that entertainment and aesthetics play a significant role in the formation of tour quality. The results of the data analysis also showed that tour quality has a positive influence on tour satisfaction, which in turn positively affects word-of-mouth. Furthermore, a tour guide service moderated the relationship between aesthetics and tour quality.

1. Introduction

Korea has a high proportion of elderly people in its population, because it has one of the fastest aging populations in the world. The elderly population aged 65 or older was approximately 9,000,000 in 2022, which accounts for 17.5% of the total population [1]. In addition, the proportion of the elderly population is expected to increase rapidly from 15.7% in 2020, exceed 20% in 2025, exceed 30% in 2035, and exceed 40% in 2050 [2]. These statistics show that it is anticipated that the senior tourism industry in Korea will experience significant growth [3], because travel provides health benefits, which include reducing stress, improving people’s moods, and promoting physical activity [4].

This study tries to explain the importance of experience economy in senior tourism. The 4Es or experience economy model created by Pine and Gilmore in 1999 has gained significant popularity and is frequently utilized for comprehending tourist characteristics [5,6,7]. In particular, Hwang and Lee [3] applied the experience economy framework to senior tourists and showed its internal consistency and validity in the senior tourism market. Pine and Gilmore’s framework comprises four components: education, entertainment, aesthetics, and escapism. These components are categorized based on the level of consumers’ engagement and emotional attachment to specific events or performances. It is more important than anything else to provide them with a memorable experience in order to increase travel satisfaction [8]. An experience is defined as an event that engages an individual personally, and it is crucial in regards to influencing consumer behavior, because consumers are more attracted to experiential benefits, which include fun, fantasies, and emotions [9,10]. This means that tourists tend to seek experiences that will create lasting memories and emotions in the field of tourism as opposed to just visiting a destination for its sights and attractions. It is therefore required to develop travel packages that can provide tourists with unforgettable experiences [5]. There have been very few studies that are related to experience economy in the field of tourism for the elderly, so studies that predict tourist behavior by applying experience economy have been continuously conducted in the tourism industry.

In addition, it is necessary to identify the role of tour guide services as a moderator in regards to explaining the formation of tour quality, because tour guides play an important role in giving tourists the moment of truth in package tours [11]. Tourist guides are more important for elderly tourists than for young tourists because elderly tourists expect more from tour guides during the tour [12]. For this reason, this study aims to determine what effect the tour guide service has on the relationship between experience economy and tour quality.

In summary, the current study was designed in order to examine the importance of the experience economy in the field of senior tourism. The objectives of this study were more specifically to investigate (1) the effect of the four dimensions of the experience economy, which include education, entertainment, aesthetics, and escapism, on tour quality; (2) investigate the influences of tour quality on tour satisfaction and word-of-mouth; (3) investigate the relationship between tour satisfaction and word-of-mouth; and (4) investigate the moderating role of a tour guide service in the relationship between the experience economy and tour quality. In order to achieve the objective, this study used an AMOS program, which included confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling analysis. The results of this study would confirm and extend the existing literature by empirically finding the important role of the experience economy in the senior tourism industry and its impact on outcome variables with the moderating role of tour guiding service. In addition, the results of this study will provide important information to travel agencies that operate elderly tourism packages.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Experience Economy

According to Oh, Fiore, and Jeong [5], consumers no longer solely seek products/services. They seek unique and memorable experiences. A memorable experience means that tourists are positively and consistently recalling good experiences [13]. For this reason, companies are required to incorporate value into their offerings that can stimulate unforgettable and satisfactory experiences, because high-quality products or services are no longer sufficient. Pine and Gilmore’s [14] experience economy, or 4Es, has become a well-known and widely used framework in regards to understanding consumer experiences. The concept of memorable experience is a larger concept than experience economy. That is, the conceptualization of memorable experience in detail is experience economy. Pine and Gilmore’s framework includes four dimensions: education, entertainment, aesthetics, and escapism, and they are classified based on the level of consumer involvement and connection to particular events or performances.

First, the dimension of education is related to the desire to learn something new [14]. This dimension is classified as active participation, because the participants need to have an enthusiastic attitude towards events or performances in order to improve their knowledge, skills, and abilities. The output level of the educational experience therefore depends on the participant’s attitudes [5]. The educational experience is additionally considered absorptive, because the participants’ attention is captured by implanting experiences into their minds [14]. A good example of the educational experience is the Statue of Liberty. The tourists can learn about the history of the independence of the United States of America when they visit the Statue of Liberty in New York City.

The second dimension of the experience economy is entertainment. Entertainment is defined as the act of amusing or entertaining people [15]. It is perceived as a passive activity, because people enjoy watching without actively participating in the events or performances [8]. Moreover, Pine and Gilmore [14] suggested that entertainment is absorptive, because the participants tend to intently focus on the attractive aspects of the performances or events. For instance, tourists can enjoy just watching the Fremont Street Experience or the Silverton Hotel Aquarium in Las Vegas without actively taking part.

Third, the concept of aesthetics in the experience economy refers to how consumers perceive the physical environment [16]. Aesthetics is characterized by passive participation, which is where the participants observe or are easily impacted by the sensory appeal of events or performances [5]. Aesthetics can also be considered as immersion, because the participants are fully engaged in the events or performances [14]. For instance, Yellowstone National Park, which is located in the Western United States, is renowned for its geothermal features and also wildlife. The tourists visit to see the features and wildlife without changing or affecting its current condition as observers.

Fourth, individuals seek change, which is due to the monotony of daily life, and one significant method of breaking free from the tedium is by traveling, which offers mental and physical relaxation [5,16]. Escapism involves active participation, because it necessitates a passionate attitude towards performances or events. Furthermore, it falls under the immersion category, because people become entirely engrossed in the events or performances [14,16]. For instance, one of the adventure sports, which is paragliding, allows people to perceive a high level of escapism.

The experience economy highly relates to tourist behavior. The experience economy updated in 2011 also stated that tourists want various experiences, such as holidays abroad, cultural events, nature experiences in destination, and dining experiences [17]. Penn [18] and Yeoman and McMahon-Beattie [19] noted that micro trends illustrate the changes that are occurring in the experience economy and that they are consumer-focused. Thus, numerous researchers applied the experience economy and its four sub-constructs in the tourism context [3,5,8]. Oh et al. [5] proposed the measurement scale of the experience economy for the context of tourism research by conducting preliminary qualitative studies and field surveys. Furthermore, Song et al. [8] applied the experience economy and investigated its effect on perceived value in the context of temple stay. They found that education, entertainment, and escapism affect perceived functional value, and entertainment, aesthetics, and escapism affect perceived emotional value. Hwang and Lee [3] also demonstrated that the four constructs of the experience economy play significant roles in forming tourists’ well-being perception. Extant studies support that the experience economy robustly relates to tourist behavior, so the present study applied the experience economy in the context of senior tourism.

2.2. Effect of Economy Experience on Tour Quality

According to Hwang and Lee [20] (p. 2191), tour quality can be defined as “traveler’s evaluation about the overall excellence of a tour”, and they suggested that tour quality is viewed as a crucial factor in regards to evaluating tourist satisfaction, which positively impacts revisit intentions and word-of-mouth. Several of the previous studies concentrated on increasing tour quality for this reason [20,21,22].

The consumers are more interested in experiential benefits that provide them with pleasurable feelings, exciting fantasies, and enjoyable activities [10,23,24]. These types of experiences are, more importantly, a key factor that affects tour quality [25]. This means that if tourists have a great experience, such as education, entertainment, aesthetics, and escapism, they would think that the package tour provides good quality. The empirical research also supported this relationship. For example, Oh, Fiore, and Jeoung [5] examined the effect of experience economy on the overall perceived quality using 419 samples, and they found that esthetics has a positive influence on the overall perceived quality. In addition, Rajaobelina [26] explored the impact of the customer experience on relationship quality with 289 adult respondents from a panel of individuals who reside in Canada. The results of the data analysis indicated that customer experience is an important factor that affects relationship quality. More recently, Moon and Han [27] developed a research model in order to identify the importance of experience in the tourism industry. They suggested that the experience provided by travel destinations plays an important role in enhancing the value of travelers. This study proposed the following hypotheses, which are based on the theoretical and empirical backgrounds.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Education has a positive effect on tour quality.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Entertainment has a positive effect on tour quality.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Aesthetics has a positive effect on tour quality.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Escapism has a positive effect on tour quality.

2.3. Effect of Tour Quality on Tour Satisfaction

Travel satisfaction can be viewed as a tourist’s emotional response, which is based on his/her cognitive evaluation of the travel [28]. The concept originated from Oliver’s expectancy–disconfirmation paradigm [29], which proposed that the customers have a particular set of expectations when they purchase a tour package, which was based on their prior experiences. This means that the travelers will be satisfied if the travel exceeds their expectations, and the travelers will be dissatisfied if the travel is lower than expected.

In addition, it is widely known that tour quality is an important antecedent of tour satisfaction [15,20,24,25]. For example, Lee, Jeon, and Kim [30] proposed a theoretical model in order to explore the effect of tour quality on tour satisfaction using the case of Chinese tourists in Korea. Their data analysis results indicated that tour quality helps in order to enhance tour satisfaction. More recently, Hwang, Asif, and Lee [25] collected data from duty-free travelers in order to find the relationship between tour quality and tour satisfaction. They suggested that tour quality positively affects tour satisfaction. In addition, Hwang and Lee [20] examined the significance of tour quality, and they revealed that tour quality is an important predictor of tour satisfaction. The following hypothesis is proposed as a result of the above arguments.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Tour quality has a positive effect on tour satisfaction.

2.4. Effect of Tour Quality on Word-of-Mouth

Word-of-mouth is defined as “informal, person to person communication between a perceived noncommercial communicator and a receiver regarding a brand, a product, an organization or a service” [31] (p. 63). The customers are inclined to share the positive aspects of the products or services with others when they are happy with certain products or services [31,32]. In addition, it is commonly acknowledged that word-of-mouth has more impact than commercial advertising when it comes to selecting products or services, because the information is obtained from acquaintances, such as family, relatives, and friends [33].

The current study suggests the effect of tour quality on word-of-mouth, which is based on empirical studies. Liu and Lee [34] collected data from 484 low-cost airline passengers in order to identify the relationship between service quality and word-of-mouth. They showed that good service quality leads to positive word-of-mouth. Wang, Tran, and Tran [35] additionally examined how perceived quality affects word-of-mouth, which is based on 303 domestic tourists. They argued that perceived quality plays an important role in the formation of word-of-mouth. As a result, it is reasonable to propose the following hypothesis, which is based on the empirical backgrounds. Hwang, Asif, and Lee [25] investigated the relationship between tour quality and word-of-mouth in the tourism industry. They found that when tourists perceive a high level of tour quality, they are more likely to say positive things to others.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Tour quality has a positive effect on word-of-mouth.

2.5. Effect of Tour Satisfaction on Word-of-Mouth

This study proposed the relationship between tour satisfaction and word-of-mouth, which is based on the following theoretical and empirical evidence. It is widely known that customers with a high level of satisfaction tend to have a favorable behavioral intention [36,37]. For example, Huang, Weiler, and Assaker [38] developed a research model in order to find the effect of satisfaction on behavioral intentions. They collected data from 287 Chinese tourists and suggested that the tourists are more likely to have a high level of behavioral intentions when they are satisfied. Wang, Tran, and Tran [35] also examined how satisfaction affects word-of-mouth using 303 domestic tourists. They revealed that satisfaction is an important predictor of word-of-mouth. Recently, Preko, Mohammed, Gyepi-Garbrah, and Allaberganov [39] proposed a relationship between tour satisfaction and word-of-mouth in the tourism industry. They suggested that tour satisfaction has a positive influence on word-of-mouth. As a result, the following hypothesis is therefore proposed.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Tour satisfaction has a positive effect on word-of-mouth.

2.6. The Moderating Role of Tour Guiding Service

A tour guide refers to “a person who guides groups or individuals on visits around the buildings, sites, and landscapes of a city or region and who interprets in the language of the visitor’s choice, the cultural, natural heritage, and environment” [40] (p. 178). Tour guides are commonly referred to as coordinators, information providers, and sources of knowledge during travel packages for this reason [41,42]. Tour guides play a critical role in tour packages, because they act as a bridge between tourist destinations and visitors [43]. The quality of their services is therefore crucial in regards to determining tourist experiences [44,45].

This means that even if the travelers have a great experience at a destination, they would think that the quality of the trip will not be good if the guide service is not good. Thus, this study proposed the moderating role of a tour guide service in the relationship between experience economy and tour quality.

Hypothesis 8a (H8a).

The tour guide service moderates the relationship between education and tour quality.

Hypothesis 8b (H8b).

The tour guide service moderates the relationship between entertainment and tour quality.

Hypothesis 8c (H8c).

The tour guide service moderates the relationship between aesthetics and tour quality.

Hypothesis 8d (H8d).

The tour guide service moderates the relationship between escapism and tour quality.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Model

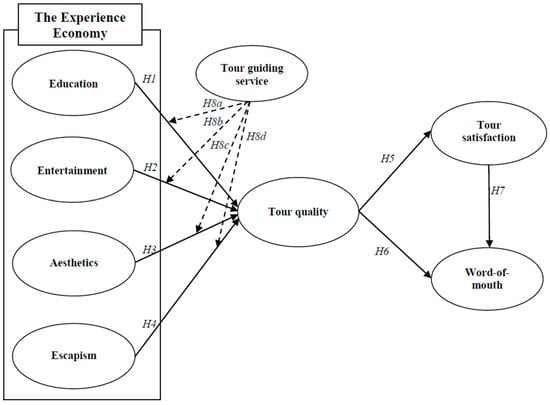

Figure 1 shows the research model, which was developed based on the eight hypotheses that are presented in the theoretical background.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual model.

3.2. Measurement Items

A total of seven concepts were measured that were based on the measurement items whose reliability and validity were evaluated by the previous studies in the tourism industry. First, 16 measurement items were cited from Hosany and Witham [16] and Oh et al. [5] in order to measure the experiential economy, which includes education, entertainment, aesthetics, and escapism. Three measurement items were used in studies by Oh [46] and Taylor and Baker [47] for tour quality, and three measurement items for tourism satisfaction were cited in studies by Chang [48] and Lee et al. [30]. Three measurement items from Hennig-Thurau, Gwinner, and Gremler [49] were used in the study for word-of-mouth. Finally, this study cited three measurement items from Jin, Lin, and Hung [50] for tour guide services, which included the following factors: the tour guide service was effective, the tour guide’s communication skills were excellent, and the tour guide’s attitude was good. The measurement items of each concept were measured using a 7-point Likert’s scale, which ranged from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. Statistical analysis in this study was performed using two pieces of software: SPSS for descriptive statistics and AMOS for testing the measurement model and structural model.

3.3. Data Collection

A face-to-face survey was conducted in Seoul, Korea. The target sample was elderly tourists who had experienced an overseas package tour within the last 6 months. In other words, the respondent is an elderly person who purchases package products in Korea and travels abroad from Korea. The legal standard for an elderly person in Korea is 65 years of age, so the survey began after confirming that the respondents were 65 years of age or older before starting the survey. The purpose of the survey was clearly explained to the respondents, and the interviewer explained questions that were confusing or unknown during the survey in order to enhance the understanding of the survey. A total of 400 questionnaires were distributed, and 382 of them were collected. Finally, 59 samples, which included insincere respondents and multivariate outliers, were deleted, and 323 samples were used for the final statistical analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the respondents. There were 95 (29.4%) respondents, and there were 228 female respondents. In addition, there were slightly more people in their 60s, which totaled 58.2%, (n = 188) than people in their 70s, which totaled 41.8%, (n = 135), and the average age was 69.16 years old. More than half of the respondents (55.1%) were college graduates (n = 178), and most of them, totalling 96.6%, were married (n = 312). Finally, 22% (n = 71) of the respondents reported that their monthly income was between USD 3001.00 and USD 4000.00.

Table 1.

Respondent profile (n = 323).

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

This study employed an AMOS (Analysis of Moment Structures) program for confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling analysis. Table 2 shows the results of the confirmatory factor analysis. The factor loadings of all measurement items of the seven concepts were found to exceed 0.807, and the p-value showed that the statistical significance level was also less than 0.001. The statistical fit level of the measurement model is also indicated in Table 2 (χ2 = 754.861, df = 250, χ2/df = 3.019, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.934, IFI = 0.955, CFI = 0. 955, TLI = 0.946, and RMSEA = 0.079). The results fitted the standard value that χ2/df was less than 5.0, all index values (NFI, IFI, CFI, and TLI) were over 0.9, and RMSEA was less than 0.08 [51].

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis: Items and loadings.

The results of the correlation analysis between the construct concepts are shown in Table 3. The composite reliabilities of the seven proposed concepts ranged from 0.942 to 0.959, the average variance extracted value of each concept exceeded ranged from 0.803 to 0.887, and the square value of the correlation coefficient between all concepts was lower than the average variance extracted value. The results indicated that internal consistency (CR > 0.7), convergent validity (AVE > 0.5), and discriminant validity (correlation2 < AVE) satisfied the cutoff [51,52]

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and associated measures.

4.3. Structural Equation Model Analysis

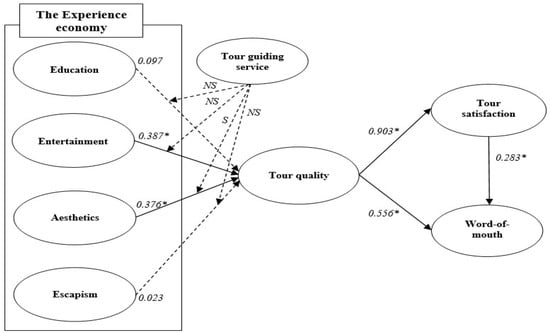

Table 4 shows the results of the structural equation model analysis, which was conducted for testing the proposed hypotheses. The results showed the statistical goodness level that was suggested by Anderson and Gerbing [51] (χ2 = 815.882, df = 258, χ2/df = 3.162, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.929, IFI = 0.950, CFI = 0.950, TLI = 0.942, and RMSEA = 0.082). According to the results of statistical analysis, among the four sub-dimensions of experience economy, entertainment (β = 0.387 and p < 0.05) and aesthetics (β = 0.376 and p < 0.05) had a significant effect on tour quality, so Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3 were accepted. Furthermore, tour quality had a positive effect on tourism satisfaction (β = 0.903 and p < 0.05) and word-of-mouth (β = 0.556 and p < 0.05), so Hypothesis 5 and Hypothesis 6 were accepted. Finally, tourism satisfaction was found to play an important role in regards to forming word-of-mouth (β = 0.283 and p < 0.05), so Hypothesis 7 was accepted.

Table 4.

Standardized parameter estimates for structural model.

4.4. The Result of Moderating Role of Tour Guiding Service

A multi-group analysis was performed in order to verify the moderating role of tour guide services. A multi-group analysis is a statistical method that identifies the moderating effect based on the χ2 difference between the path coefficients of the constrained model and the path coefficients of the unconstrained model. Hypothesis 8b and Hypothesis 8c were tested in this study by using the median value of the tour guide service in order to divide them into groups that perceived the tour guide service as low (n = 152) and a group that perceived the tour guide service as high (n = 171). The change in χ2 was 1.101 in regards to the moderating role of the tour guide service between entertainment and tour quality, which was lower than the χ2 standard value of 3.84 for df = 1, so H8b was rejected. Hypothesis 8c was accepted for the moderating role of tour guide service between aesthetics and tour quality, because the change in χ2 was 5.713. In other words, it can be interpreted that tourists who highly perceived the tour guiding service (β = 0.391) thought the tour quality was better when experiencing aesthetic, compared to tourists who perceived the tour guide service poorly (β = 0.252).

4.5. Hypothesis Outcomes

The results of the hypothesis tests are indicated in Figure 2. First, entertainment and aesthetics play positive roles in enhancing senior tourists’ tour quality (H2, H3), whereas education and escapism did not significantly affect tour quality (H1, H4). In addition, the tour quality led to tour satisfaction and word-of-mouth (H5, H6), and tour satisfaction also positively affected word-of-mouth (H7). Lastly, the test of moderating role indicated that if senior tourists experienced better tour guiding services, they more positively perceived the tour quality when evaluating the tour quality driven by aesthetics (H8c).

Figure 2.

Standardized theoretical path coefficients. Note: * p < 0.05, S = Supported, and NS = Not supported.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First of all, the present study successfully investigated the crucial role of the experience economy in regards to forming tour quality. The study focused on the growth of the senior tourism industry in Korea, which is due to the aging population. The travelers tend to seek unique and memorable experiences [5,8], so this study applied the four constructs of the experience economy: education, entertainment, aesthetics, and escapism, by Pine and Gilmore [14] as predictors of tour quality. The results indicated that entertainment and aesthetics had positive effects on tour quality. However, the effects of education and escapism on tour quality were not statistically supported despite their important role in the tourism context. It can be inferred that elderly tourists have already had several tourism experiences and possess certain knowledge, so educational experience elements did not affect tour quality. In addition, escapism may not have been as important to the tour quality for older tourists who are already of retirement age. On the other hand, Hwang and Lee [3] identified that education and escapism influence well-being perception in the senior tourism context. It can be interpreted that education and escapism are crucial elements in regards to forming the well-being perception of elderly tourists, and not the elements of tour quality. This study identifies the role of the sub-dimensions of the experience economy in the senior tourism context according to these findings and discussions.

This study also demonstrated the consequences of tour quality. The study hypothesized the relationship between tour quality, satisfaction, and word-of-mouth, which was grounded in previous research [25,34,35]. The results indicated that tour quality for the elderly positively affects satisfaction and word-of-mouth, and satisfaction also significantly influences word-of-mouth. The study emphasized the essential role of tour quality in the context of the experience of tourism for the elderly.

Lastly, the present study proved the moderating role of tour guide services between the experience economy and tour quality in tourism for the elderly context. The study focused on tour guide services as a moderator, because tour guides play a critical role in tour packages because they act as a bridge between tourist destinations and visitors [43]. Tour guides also hold a significant role in senior tourism, because elderly travelers often face challenges, such as physical limitations, compared to younger tourists [12]. The result of the hypotheses test indicated that tour guide services significantly strengthen the effect of aesthetic experience on tour quality. The study presents theoretical contributions, because it presents the first findings of the moderating role of tour guide services between the experience economy and tour quality.

5.2. Managerial Implications

The present study revealed that entertainment had a positive effect on tour quality. Tour guides should amuse elderly tourists by adding entertainment elements as opposed to educational elements. For instance, tour guides could construct interesting storytelling by citing famous dramas when the elderly tourists are guided to historical destinations. Moreover, the guides could take funny photos with the tourists by preparing costumes or props that are related to the tourist destination. These types of efforts would contribute to improving the tour quality for the elderly.

In addition, the managers should consider the aesthetic element of the destination in regards to establishing tour plans for elderly tourists. Tourism plans can be configured in various ways according to the purpose of the tourist, such as heritage, rural, and food tourism [53,54,55]. The managers should focus on the selection of aesthetic tourist destinations, and the guides could organize a pleasant trip, as suggested above. The attractiveness, atmosphere, and harmony with the environment of the sightseeing destination can be considered, which are in the measurement items of this study.

The effect of the aesthetic experiences of the elderly tourists on tour quality is more importantly strengthened by tour guide services. It can be interpreted that tourists who highly perceived a tour guide service thought that the tour quality was better when experiencing aesthetics compared with tourists who perceived the tour guide service poorly. The extant studies emphasized customer orientation and communication effectiveness in a tour guiding service context [11,42,56]. The managers should develop a service manual that takes into account the physical limitations of elderly tourists, such as their movement speed in tourist destinations, the need for escort services, the pace of the conversation, and the tone of voice used by the guides.

6. Conclusions

The present study focused on the senior tourist market’s recent growth, so the study investigated the importance of the experience economy in the senior tourism industry. This study more specifically hypothesized the effects of the four dimensions of the experience economy, education, entertainment, aesthetics, and escapism, on tour quality, and the effects of tour quality on tour satisfaction and word-of-mouth. The framework was strengthened by investigating the moderating role of tour guide services in the relationship between the experience economy and tour quality. The results indicated that entertainment and aesthetics affect tour quality and lead to tour satisfaction and word-of-mouth, and satisfaction influences word-of-mouth. Moreover, tour guide services strengthened the effect of aesthetics on tour quality. These findings presented theoretical contributions, because the influence of the experience economy was investigated in the senior tourism context, which produced the first finding of the moderating role of guiding services between the experience economy and tour quality. It also presented practical suggestions for tour guide services and establishing tour product plans in order to enhance the quality of tours for elderly travelers.

Nevertheless, this study has some research limitations. First, the data might have the likelihood of a common method bias, because this study’s constructs were measured using only one survey [57]. It is suggested to consider the data collection methods, which can diminish the likelihood of this issue in future research. Second, the results have the limitation of generalizability, because the study collected samples only from Korea, so future research is necessary to test a proposed model of this study in other areas. Lastly, nostalgia can influence the individuals’ responses and behavior. For instance, Hwang and Hyun [58] identified that certain nostalgia triggers affect emotional responses and lead to revisit intentions in the hospitality context. The elderly tourists already have a lot of various tourism experiences, so nostalgia for a certain tourist destination can affect their emotional response. A study regarding elderly tourists’ nostalgia for tourist destinations and either its consequences or the moderating role of it is suggested.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and J.M.; methodology, J.H. and J.M.; software, J.H.; validation, J.H.; formal analysis, K.J.; investigation, K.J., J.H. and J.M.; resources, J.M.; data curation, K.J. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H. and J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.H. and K.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- KDI. Senior Population Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://eiec.kdi.re.kr/policy/materialView.do?num=230699&topic= (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- KOSIS. Korea by Population. 2022. Available online: https://kosis.kr/visual/populationKorea/PopulationByNumber/PopulationByNumberMain.do?mb=Y&menuId=M_1_4&themaId=D03 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Petrick, J.F. Health and wellness benefits of travel experiences: A literature review. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeong, M. Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. Experience economy in hospitality and tourism: Gain and loss values for service and experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M.; Engen, M. Pine and Gilmore’s concept of experience economy and its dimensions: An empirical examination in tourism. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 12, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Lee, C.K.; Park, J.A.; Hwang, Y.H.; Reisinger, Y. The influence of tourist experience on perceived value and satisfaction with temple stays: The experience economy theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Spiller, N.; Noci, G. How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. Eur. Manag. J. 2007, 25, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B.; Zarantonello, L. Consumer experience and experiential marketing: A critical review. Rev. Mark. Res. 2013, 10, 25–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Q.; Chow, I. Application of importance-performance model in tour guides’ performance: Evidence from mainland Chinese outbound visitors in Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Teng, H.Y. Exploring tour guiding styles: The perspective of tour leader roles. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, K.W. The antecedents and consequences of golf tournament spectators’ memorable brand experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster. Search for a Word. 2022. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Hosany, S.; Witham, M. Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Penn, M. Microtrends: The Small Forces behind Tomorrow’s Big Changes; Twelve Books: Hachette, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yeoman, I.S.; McMahon-Beattie, U. The experience economy: Micro trends. J. Tour. Futures 2019, 5, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J.J. Understanding customer-customer rapport in a senior group package context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2187–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Hudson, P.; Miller, G.A. The measurement of service quality in the tour operating sector: A methodological comparison. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, C.A.; Muhlemann, A.P. The implementation of total quality management in tourism: Some guidelines. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Merging the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior in the context of drone food delivery services: Does the level of product knowledge really matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B.H.; Zarantonello, L.; Brakus, J.J. Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Asif, M.; Lee, K.W. Relationships among country image, tour motivations, tour quality, tour satisfaction, and attitudinal loyalty: The case of Chinese travelers to Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaobelina, L. The impact of customer experience on relationship quality with travel agencies in a multichannel environment. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Tourist experience quality and loyalty to an island destination: The moderating impact of destination image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.Y.; To, C.K.M.; Chu, W.C. Desire for experiential travel, avoidance of rituality and social esteem: An empirical study of consumer response to tourism innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2016, 1, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeon, S.; Kim, D. The impact of tour quality and tourist satisfaction on tourist loyalty: The case of Chinese tourists in Korea. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, H. Perceived innovativeness of drone food delivery services and its impacts on attitude and behavioral intentions: The moderating role of gender and age. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Kim, J.J. Emotional attachment, age and online travel community behaviour: The role of parasocial interaction. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3466–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Nam, M.; Kim, I. The effect of trust on value on travel websites: Enhancing well-being and word-of-mouth among the elderly. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.S.; Lee, T. Service quality and price perception of service: Influence on word-of-mouth and revisit intention. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2016, 52, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.L.; Tran, P.T.K.; Tran, V.T. Destination perceived quality, tourist satisfaction and word-of-mouth. Tour. Rev. 2017, 72, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin Jr, J.J.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Kim, I.; Hwang, J. A change of perceived innovativeness for contactless food delivery services using drones after the outbreak of COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Weiler, B.; Assaker, G. Effects of interpretive guiding outcomes on tourist satisfaction and behavioral intention. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preko, A.; Mohammed, I.; Gyepi-Garbrah, T.F.; Allaberganov, A. Islamic tourism: Travel motivations, satisfaction and word of mouth, Ghana. J. Islam. Mark. 2021, 12, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.; Ham, S. Improving the quality of tour guiding: Towards a model for tour guide certification. J. Ecotour. 2005, 4, 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. The tourist guide: The origins, structure and dynamics of a role. Ann. Tour. Res. 1985, 12, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.C. Effects of tour leader’s service quality on agency’s reputation and customers’ word-of-mouth. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 14, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J.; Wong, K.K. Case study on tour guiding: Professionalism, issues and problems. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Hsu, C.H.; Chan, A. Tour guide performance and tourist satisfaction: A study of the package tours in Shanghai. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 34, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Lin, M.L.; Chen, Y.C. How tour guides’ professional competencies influence on service quality of tour guiding and tourist satisfaction: An exploratory research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2017, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H. The effect of brand class, brand awareness, and price on customer value and behavioral intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2000, 24, 136–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.A.; Baker, T.L. An assessment of the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction in the formation of consumers’ purchase intentions. J. Retail. 1994, 70, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.C. Examining the effect of tour guide performance, tourist trust, tourist satisfaction, and flow experience on tourists’ shopping behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Lin, V.S.; Hung, K. China’s Generation Y’s expectation on outbound group package tour. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What is food tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. What is rural tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. The core of heritage tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A.H.; Wong, K.K.; Chang, R.C. Critical issues affecting the service quality and professionalism of the tour guides in Hong Kong and Macau. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1442–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; Hyun, S.S. The impact of nostalgia triggers on emotional responses and revisit intentions in luxury restaurants: The moderating role of hiatus. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).