Awareness Level of Spatial Planning Tools for Disaster Risk Reduction in Informal Settlements in Mopani District, South Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of SPLUMA on Informal Settlements

1.2. The Role of Spatial Planning Tools in Disaster Risk Reduction in Informal Settlements

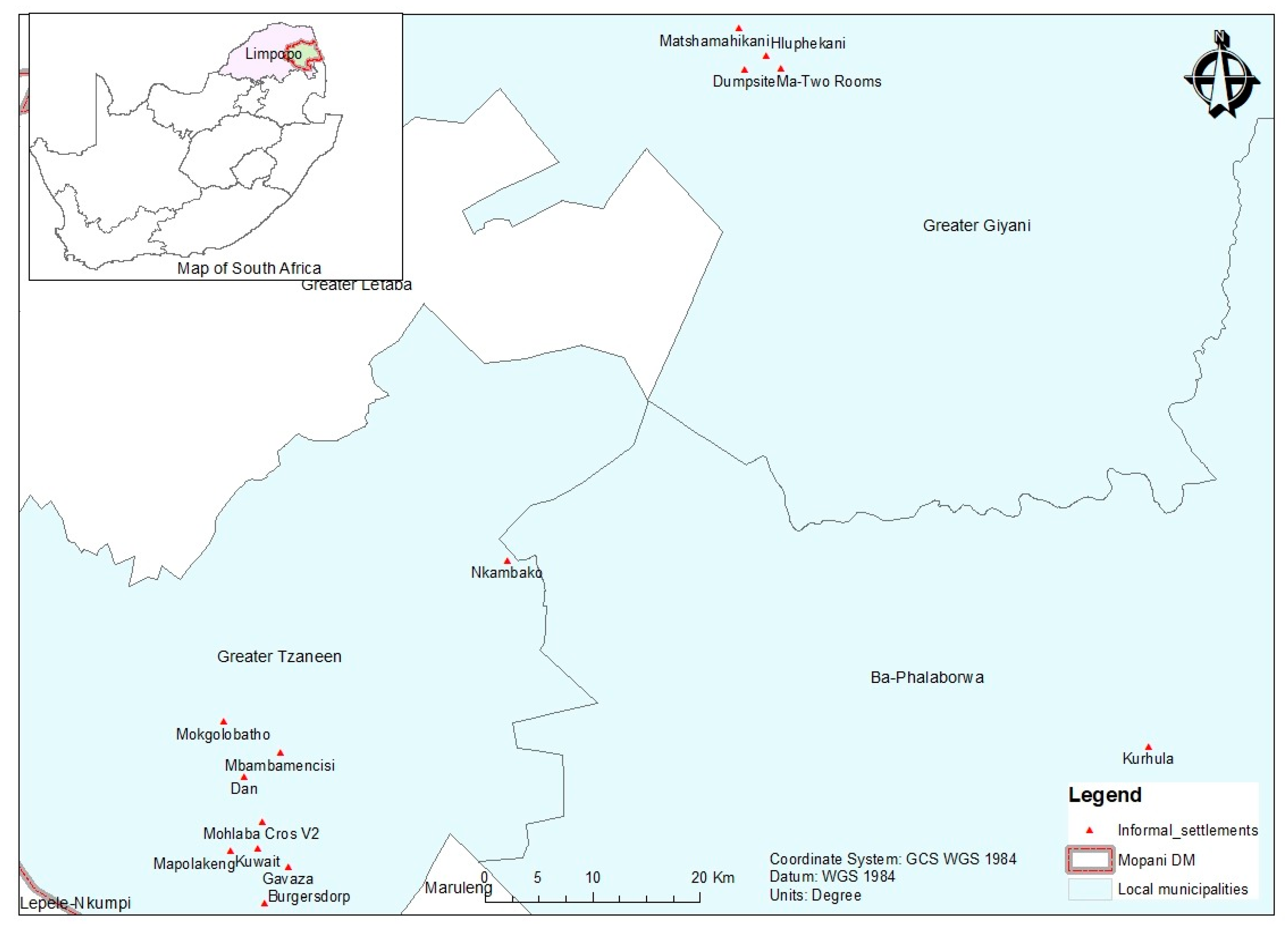

2. Overview of the Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

Relative Importance Index (RII) Analysis

- ○

- “W” is the weight given to each awareness factor by the respondent within the range {1, 2, 3, 4 and 5}, multiplied by the number of respondents {n1, n2, n3, n4, n5} for each factor;

- ○

- “n1” = number of respondents who were not at all aware;

- ○

- “n2” = number of respondents who were slightly;

- ○

- “n3” = number of respondents who were somewhat aware;

- ○

- “n4” = number of respondents who were moderately aware;

- ○

- “n5” = number of respondents who were extremely aware;

- ○

- “A”: highest weight (in this study: 5);

- ○

- “N”: overall number of respondents (returned questionnaires: 605)

4. Results

4.1. Social-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

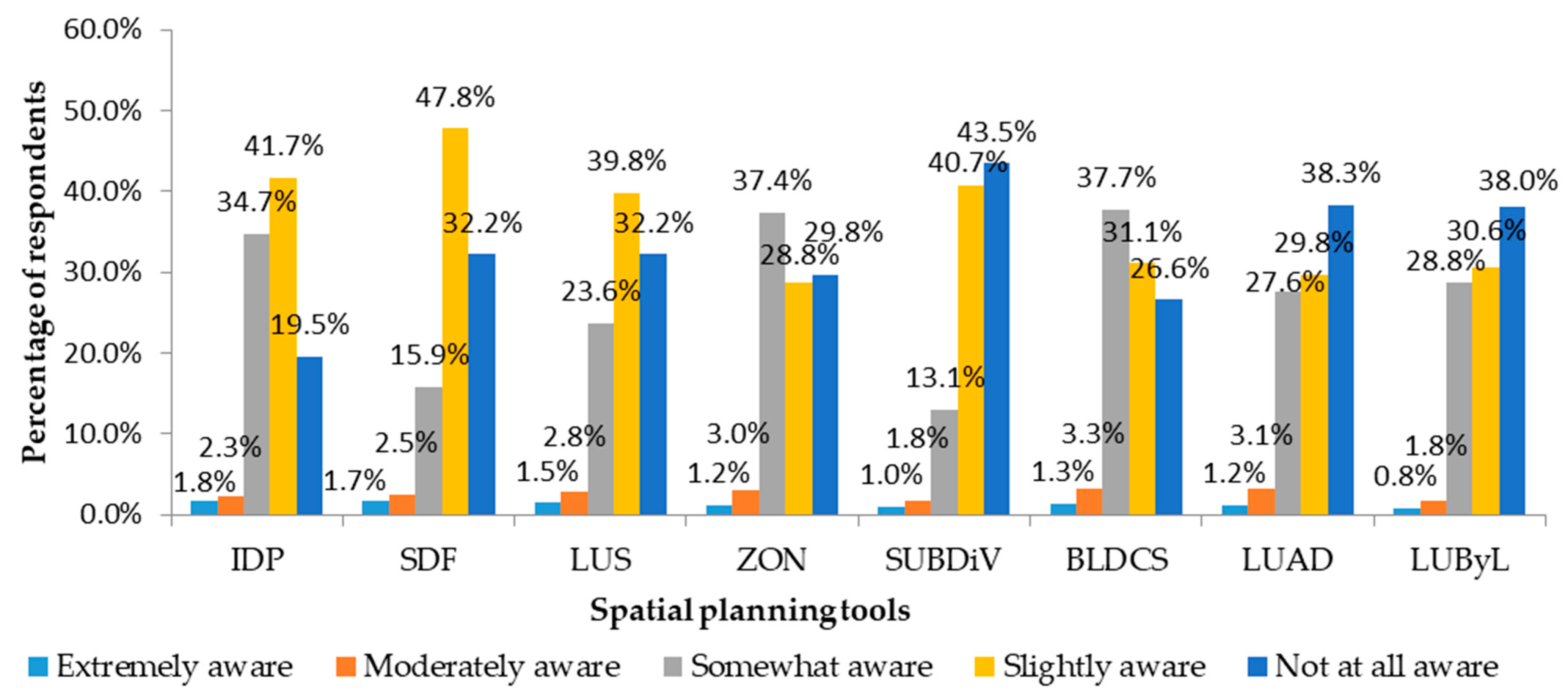

4.2. Awareness Level of Spatial Planning Tools

4.3. Differences in Awareness Levels of Spatial Planning Tools Based on the Social-Demographics of Respondents

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akola, J.; Chakwizira, J.; Ingwani, E.; Bikam, P. An AHP-TOWS Analysis of Options for Promoting Disaster Risk Reduction Infrastructure in Informal Settlements of Greater Giyani Local Municipality, South Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omid, M. Strategic planning and urban development by using the SWOT analysis. The case of Urmia city. Rom. Rev. Reg. Stud. 2014, 10, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Somiah, M.; Ayarkwa, J.; Agyekum, K. Assessing House-Owners’ Level of Awareness on the National Building Regulations, L.I. 1630, in the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis. African J. Appl. Res. 2015, 1, 170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Belle, J.A.; Collins, N.; Jordaan, A. Managing wetlands for disaster risk reduction: A case study of the eastern Free State, South Africa. Jamba J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2018, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mtani, I.W.; Mbuya, E.C. Urban fire risk control: House design, upgrading and replanning. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2018, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, M. A historical exposition of spatial injustice and segregated urban settlement in South Africa. Fundamina 2019, 25, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliades, F.; Doula, M.K.; Papamichael, I.; Vardopoulos, I.; Voukkali, I.; Zorpas, A.A. Carving out a Niche in the Sustainability Confluence for Environmental Education Centers in Cyprus and Greece. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akola, J.; Chakwizira, J.; Ingwani, E.; Bikam, P. The Contribution of Spatial Planning Tools towards Disaster Risk Reduction in Informal settlement in South Africa. In Sustainanble and Smart Spatial Planing in Africa, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Abingdon, UK, 2022; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. 2018 Review of SDGs Implementation: SDG 11—Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaruddin, S.M.; Ahmad, P.; Alwee, N. Community Awareness on Environmental Management through Local Agenda 21 (LA21). Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 222, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan Çimşir, B.T.; Uzunboylu, H. Awareness Training for Sustainable Development: Development, Implementation and Evaluation of a Mobile Application. Sustainability 2019, 11, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Building Regulation for Resilience: Managing Risks for Safer Cities; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- South African Cities Network (SACN). SPLUMA as a Tool for Spatial Transformation; South African Cities Network: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dewald, N. Introduction To Disaster Risk Reduction; USAID: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 59.

- ARUP. A Framework for Fire Safety in Informal Settlements; Arup International Development: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Human Settlement (DHS). Official Guide to South Africa 2020/21; DHS: Pretoria, South Africa, 2020.

- Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft. WorldRiskReport 2022: Focus Digitalization; Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.M.; Birkmann, J.; Tangwanichagapong, S.; Jamshed, A. Spatial Planning and Systems Thinking Tools for Climate Risk Reduction: A Case Study of the Andaman Coast, Thailand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, J.K.; Vidal, D.G.; Dinis, M.A.P. Raising Awareness on Solid Waste Management through Formal Education for Sustainability: A Developing Countries Evidence Review. Recycling 2021, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nembilwi, N.; Chikoore, H.; Kori, E.; Munyai, R.B.; Manyanya, T.C. The occurrence of drought in Mopani district municipality, South Africa: Impacts, vulnerability and adaptation. Climate 2021, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todes, A.; Karam, A.; Klug, N.; Malaza, N. Beyond master planning? New approaches to spatial planning in Ekurhuleni, South Africa. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Rural Development and Land Reform. Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act 16 of 2013; Rural Development and Land Reform: Pretoria, South Africa, 2013; pp. 1–72.

- Cilliers, J.; Victor, H. Considering spatial planning for the South African poor: An argument for ‘planning with’. Town Reg. Plan. 2018, 72, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Van Huyssteen, E.; le Roux, A.; van Niekerk, W. Analysing risk and vulnerability of South African settlements: Attempts, explorations and reflections. Jamba J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2013, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Rural Development and Land Reform. Land Use Scheme Guidelines; Rural Development and Land Reform: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017; pp. 1–82.

- Mopani District Municipality. Draft Reviewed Integrated Development Plan 2016–2021; Mopani District Municipality: Mopani, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Asian Development Bank. Reducing Disaster Risk by Managing Urban Land Use: Guidance Notes for Planners; Asian Development Bank: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Rural Development and Land Reform. Guidelines for the Development of Spatial Development Frameworks; No. 8. Rural Development and Land Reform; Republic of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011; pp. 9–12.

- Minnie, J. Informal Settlements Fire and Flooding Risk Reduction Strategy. In Dmisa Western Cape Provincial Workshop in July; DMISA: Germiston, South Africa, 2005; Volume 2012, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Laws Africa. Open Bylaws South Africa. 2021. Available online: https://openbylaws.org.za/about.html#:~:text=By-lawsarelawsmanagedbymunicipalities.TheConstitutionandforceasothernationalandprovinciallegislation (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- National Disaster Management Centre. Introduction: A Policy Framework for Disaster Risk Management in South Africa; National Disaster Management Centre: Pretoria, South Africa, 2005.

- Mopani District. Community Survey; Population of Mopani District; Wazi Maps: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Statistical Release Census 2011; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011; p. P0301.4.

- Mopani District Municipality. Mopani District Municipality: Draft Annual Report; Mopani District Municipality: Tzaneen, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, C.R. Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques, 2nd ed.; New Age International Publishers: New Delhi, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Somiah, M.K.; Osei-Poku, G.; Aidoo, I. Relative Importance Analysis of Factors Influencing Unauthorized Siting of Residential Buildings in the Sekondi-Takoradi Metropolis of Ghana. J. Build. Constr. Plan. Res. 2015, 3, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooshdi, R.R.R.M.; Majid, M.Z.A.; Sahamir, S.R.; Ismail, N.A.A. Relative importance index of sustainable design and construction activities criteria for green highway. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2018, 63, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Al Khatib, B.; Poh, Y.S.; El-Shafie, A. Delay factors management and ranking for reconstruction and rehabilitation projects based on the Relative Importance Index (RII). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, M.A.; Khoiry, M.A.; Hamzah, N. Using Relative Importance Index Method for Developing Risk Map in Oil and Gas Construction Projects. J. Kejuruter. 2020, 32, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, M.R.; Potdar, V. Development of an Effective System for Selecting Construction Materials for Sustainable Residential Housing in Western Australia. Appl. Math. 2020, 11, 825–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdoun, A. Academic leadership commences by self-leadership. In Proceedings of the SHS Web of Conferences EECME 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 28 May 2021; Volume 111, p. 0100. [Google Scholar]

- Tholibon, D.A.; Nujid, M.; Mokhtar, H.; Rahim, J.A.; Aziz, N.F.A.; Tarmizi, A.A.A. Relative Importance Index (RII) In Ranking the Factors of Employer Satisfaction Towards Industrial Training Students. Int. J. Asian Educ. 2021, 2, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akadir, O.P. An Analysis of Building Information Modeling (BIM) Usage in Nigerian Construction Industry. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 9, 2410–2419. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Okudan, G.E.; Riley, D.R. Sustainable performance criteria for construction method selection in concrete buildings. Autom. Constr. 2010, 19, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akadir, O.P. Development of a Multi-Criteria Approach for the Selection of Sustainable Materials for Building Projects. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chuweni, N.N.; Mohamed Saraf, M.H.; Fauzi, N.S.; Kasim, A.C. Factors Determining the Purchase Decission of Green Residential Properties in Malaysia. J. Malaysian Inst. Planners 2022, 20, 272–282. [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite, D.; Sverdlik, A. Assessing Health Risks in Informal Settlements in Sub-Saharan African Cities; Urban Africa Risk Knowledge: Holborn, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite, D.; Archer, D.; Colenbrander, S.; Dodman, D.; Hardoy, J. Responding to climate change in cities and in their informal settlements and economies. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference on Cities and Climate Change, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 5–7 March 2018; Volume 26, pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dodman, D.; Archer, D.; Mayr, M.; Engindeniz, E. Pro-Poor Climate Action in Informal Settlements; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; Volume 46, pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mamokhere, J.; Meyer, D.F. A Review of Mechanisms Used to Improve Community Participation in the Integrated Development Planning Process in South Africa: An Empirical Review. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathebula, N.E.; Nkuna, N.W.; Sebola, M.P. Integrated Development Plan for Improved Service Delivery: A Comparative Study of Municipalities Within the Mopani District Municipality, Limpopo Province. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2016, 8, 1309–8047. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, C.P.; Andrade, L.; O’neill, E.; O’malley, K.; O’dwyer, J.; Hynds, P.D. Gender-related differences in flood risk perception and behaviours among private groundwater users in the Republic of Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Florença, S.G.; Anjos, O.; Boustani, N.M.; Chuck-Hernández, C.; Sarić, M.M.; Ferreira, M.; Costa, C.A.; Bartkiene, E.; Cardoso, A.P.; et al. Are Consumers Aware of Sustainability Aspects Related to Edible Insects? Results from a Study Involving 14 Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerulli, D.; Scott, M.; Aunap, R.; Kull, A.; Pärn, J.; Holbrook, J.; Mander, Ü. The role of education in increasing awareness and reducing impact of natural hazards. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleş, A.E.; Önen, E.; Górecki, J. Determination of Green Building Awareness: A Study in Turkey. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 449 | 74% |

| Female | 156 | 26% | |

| Age groups | 15–24 yrs | 230 | 38% |

| 25–34 yrs | 217 | 36% | |

| 35–44 yrs | 89 | 15% | |

| 45–54 yrs | 64 | 11% | |

| >55 yrs | 5 | 1% | |

| Level of income | <R1000 | 254 | 42% |

| R1001–R5000 | 190 | 31% | |

| R5001–R10000 | 94 | 16% | |

| >R10000 | 67 | 11% | |

| Education level | Masters | 14 | 2% |

| Bachelors | 32 | 5% | |

| Diploma | 146 | 24% | |

| Secondary and below | 413 | 68% |

| Spatial Planning Tools | Awareness Factors | RII | Ranks | Awareness Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated Development Plan | Participation in the planning process | 0.4506 | 1 | M |

| Building codes and standards | Building standards when erecting buildings | 0.4433 | 2 | M |

| Zoning | Restrictions and permitted land uses | 0.4340 | 3 | M |

| Land Use Scheme | The purpose and specific uses of land | 0.4030 | 4 | M |

| Land use application determination | The Municipal Planning Tribunal and their role | 0.3980 | 5 | M–L |

| Land use bylaws | The spatial planning bylaws in the municipality | 0.3937 | 6 | M–L |

| Spatial Development Framework | SDF guidelines | 0.3871 | 7 | M–L |

| Sub-divisions | Land survey requirements | 0.3524 | 8 | M–L |

| Category | Characteristics | N | Statistic | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 449 | 2.08 | |

| Female | 156 | 1.92 | ||

| t | 2.27 | |||

| p | 0.012 | |||

| Age | 15–24 yrs | 230 | 1.98 | |

| 25–34 yrs | 217 | 2.05 | ||

| 35–44 yrs | 89 | 2.19 | ||

| 45–54 yrs | 64 | 1.98 | ||

| >55 yrs | 5 | 2.02 | ||

| f | 1.34 | |||

| p | 0.331 | |||

| Income level | <R1000 | 254 | 1.96 | |

| R1001–R5000 | 190 | 1.97 | ||

| R5001–R10000 | 94 | 2.09 | ||

| R10001+ | 67 | 2.48 | ||

| f | 9.87 | |||

| p | <0.001 | |||

| Education level | Masters | 14 | 2.33 | |

| Bachelors | 32 | 2.52 | ||

| Diploma | 146 | 2.10 | ||

| Secondary and below | 413 | 1.97 | ||

| f | 6.84 | |||

| p | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akola, J.; Chakwizira, J.; Ingwani, E.; Bikam, P. Awareness Level of Spatial Planning Tools for Disaster Risk Reduction in Informal Settlements in Mopani District, South Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065380

Akola J, Chakwizira J, Ingwani E, Bikam P. Awareness Level of Spatial Planning Tools for Disaster Risk Reduction in Informal Settlements in Mopani District, South Africa. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065380

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkola, Juliet, James Chakwizira, Emaculate Ingwani, and Peter Bikam. 2023. "Awareness Level of Spatial Planning Tools for Disaster Risk Reduction in Informal Settlements in Mopani District, South Africa" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065380

APA StyleAkola, J., Chakwizira, J., Ingwani, E., & Bikam, P. (2023). Awareness Level of Spatial Planning Tools for Disaster Risk Reduction in Informal Settlements in Mopani District, South Africa. Sustainability, 15(6), 5380. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065380