Abstract

Embracing net-zero principles and planet-friendly regenerative tourism practices can reduce our carbon footprint and increase momentum toward carbon neutral. The present study explored the effects of the net-zero commitment concern on regenerative tourism intention, including the moderating influence of destination competitiveness and influencer marketing on this relationship. Drawing on a survey of international expat tourists (N = 540) and partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), the present study offers ground-breaking empirical evidence on the significantly positive influence of the net-zero commitment concern on regenerative tourism intention. Importantly, the PLS-SEM estimations also validated that destination competitiveness and influencer marketing strengthened the effects of the net-zero commitment concern on regenerative tourism intention through significantly positive moderations. The present study implications offer strategic guidelines and an advancement in prior knowledge on the net-zero commitment concern, destination competitiveness, influencer marketing, and regenerative tourism intention with an aim to increase the collective global efforts toward climate action. Moreover, the present study used prominent theories (i.e., the theory of planned behavior, game theory, resilience theory, and social learning theory) to guide future investigations on the complex nexus between net-zero commitment, destination competitiveness, influencer marketing, and regenerative tourism intention.

1. Introduction

Climate change is not just a distant threat, it is a present reality with devastating consequences that demand our immediate attention and motivation for meaningful climate action [1,2]. Net zero refers to the idea of achieving a balance between the amount of greenhouse gas emissions produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere [2,3]. This concept is aimed at combating the effects of climate change, which is one of the biggest challenges facing humanity today [4]. The global commitment to net zero represents a concerted effort by countries, organizations, and individuals to take action toward this goal [1]. Net zero is a critical step toward reducing the negative impacts of climate change, such as rising temperatures, sea level rise, and more frequent extreme weather events [1,5]. This requires reducing emissions, as well as taking action to remove the existing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere [5,6]. The commitment to net zero represents a coordinated effort to address this challenge, bringing together all stakeholders to work toward a common goal. Countries and organizations that have committed to net zero are taking a leadership role in addressing this critical challenge [6,7]. This includes the adoption of more sustainable practices, investing in renewable energy sources, and supporting the development of new technologies that help reduce emissions and remove existing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. By taking these actions, countries, organizations, and individuals are working to create a more sustainable future for generations to come [4,8]. The commitment to net zero also recognizes the critical role that individuals play in addressing this challenge. From reducing energy usage at home to supporting businesses and organizations that prioritize sustainability, individuals have the power to make a difference and help reach the goal of net zero [3,9].

The global commitment to regenerative tourism has increased significantly in recent years as travelers are becoming more aware of the impact of their travel on the environment and local communities [10,11]. Regenerative tourism goes beyond eco-tourism, as it not only protects the environment but also supports the local communities and their traditional ways of life [10,12]. Many tourism organizations and governments (e.g., Hawai’i Tourism Authority) are recognizing the importance of regenerative tourism and are taking steps to promote it [11,13]. Regenerative tourism involves working closely with local communities to create sustainable travel experiences that enhance the natural and cultural heritage of a destination [11,12]. Hence, the participation of all stakeholders, including local residents, businesses, governments, and tourists, is critical. By engaging local communities, regenerative tourism helps to create a sense of ownership and pride in the destination while providing economic benefits [14,15]. In order to promote regenerative tourism, it is important to support local economies and small businesses. This can be achieved by promoting local products, supporting local crafts, and encouraging visitors to spend money in the local community. Additionally, regenerative tourism should also focus on education and awareness-raising activities that highlight the importance of preserving the local environment and culture [13,14]. Regenerative tourism is critical for ensuring the long-term sustainability of destinations and the well-being of local communities [11,12]. The promotion of regenerative tourism practices can help to protect and preserve the planet’s natural and cultural heritage for future generations to enjoy. Hence, a concerted effort from all stakeholders is vital, including tourists, governments, businesses, and local communities, to create a more sustainable and regenerative travel industry [15,16].

Destination competitiveness refers to the ability of a tourist destination to attract and retain visitors in a competitive market [17,18]. It encompasses factors such as the infrastructure, facilities, amenities, and attractions that make a destination appealing to travelers [19,20]. Influencer marketing, on the other hand, is a form of marketing that utilizes social media influencers to promote a brand or destination to a targeted audience [21,22]. When it comes to regenerative tourism, both destination competitiveness and influencer marketing play a crucial role in shaping the industry [13,17,22]. The competitive environment of a destination can drive sustainable development and the preservation of local cultural and natural resources. Influencer marketing can raise awareness about regenerative tourism, promote sustainable practices, and encourage travelers to engage in responsible tourism [14,23]. Despite a rampant scholarly focus on net zero (including a commitment to net zero) and regenerative tourism, the underlying relationship between these two constructs has rarely been studied [3,12]. Importantly, empirical evidence on the effects of destination competitiveness and influencer marketing on regenerative tourism intention (especially their moderating effects) has rarely been examined in prior research [5,11,18,21]. To address this existent and critical knowledge gap, the present study explored the effects of the net-zero commitment concern on regenerative tourism intention [3,12] and whether destination competitiveness and influencer marketing moderate this relationship [5,11,18,21].

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Net-Zero Commitment Concern

In the past decade, the effects of climate change have become increasingly visible (e.g., immense heatwaves and drought in Europe, as well as the devastating flood in Pakistan) [3,5]. Consequently, the net-zero commitment concern is a pressing issue that is gaining more attention across the globe [1,3]. This term refers to a commitment made by countries, organizations, and corporations to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to a level that is considered sustainable [5,7]. The goal of this commitment is to reach a state where the emissions that are produced are balanced by the amount that is being removed from the atmosphere, hence reaching a net-zero carbon footprint [4,8]. However, the reality of achieving this goal is far from simple, and it requires a significant effort and change in many aspects of our daily lives. There are several concerns that need to be addressed in order to reach this objective. Firstly, the rate of emissions reduction required to reach net zero is significantly higher than the current levels, and this necessitates major changes in energy generation, transportation, agriculture, and industrial processes [2,9]. This, in turn, requires a substantial investment in new technology and a shift in the way we live, work, and consume. Another major concern is that many countries and corporations have yet to fully acknowledge the magnitude of the challenge and the amount of effort required to reach net zero [6,24]. There is a tendency to focus on short-term targets and ignore the need for long-term planning and investment. This is particularly problematic in countries where political and economic factors may be prioritized over environmental concerns and where decision-makers may be reluctant to take the necessary steps to reduce emissions [2,6].

There is also a concern that reaching net zero may not be enough to prevent the worst effects of climate change, particularly if the rate of emissions reduction is not fast enough [1,5]. The planet is already experiencing the impacts of rising temperatures, melting ice caps, and extreme weather events, and more severe consequences are anticipated in the near future [7,8]. Another issue is that there is a need for international cooperation in order to achieve net zero. Different countries have different levels of emissions and different capacities to reduce them. In order to be effective, it is necessary for all countries to work together, share information and best practices, and support one another in their efforts [2,6]. However, there are often significant political and economic challenges to this cooperation, particularly between developed and developing countries, which may make it difficult to reach a shared commitment to net zero. Finally, there is also a concern that reaching net zero will not be possible without major advances in technology. For example, there are currently no viable alternatives to fossil fuels for transportation and energy generation, and the development of these technologies is slow and expensive [5,7]. Additionally, there is a need for new, effective methods of carbon capture and storage and for new technologies to enable the efficient use of renewable energy sources. Net-zero commitment is a critical issue for the future of our planet, and it requires a major effort from all of us to achieve it [4,9]. It requires a change in the way we live, work, and consume, and it requires international cooperation and investment in new technology. However, the benefits of reaching this goal are significant, and it is essential that all stakeholders (including businesses, governments, and civil society) work together to make it a reality [6,24].

2.2. Regenerative Tourism Intention

Globally, regenerative tourism is a growing movement in the travel and tourism industry that aims to create positive and long-lasting impacts on the communities, ecosystems, and cultures that host travelers [10,12]. It is a form of responsible tourism that goes beyond simply minimizing harm and seeks to actively restore, revitalize, and regenerate the natural and cultural systems that make a destination unique [11,13]. Regenerative tourism is founded on the belief that travel can play a transformative role in shaping a more sustainable and equitable world. Rather than just exploiting the resources of a destination, regenerative tourism seeks to support local communities, conserve natural resources, and protect cultural heritage [14,15]. It prioritizes the well-being of people and the planet over profit and seeks to create a truly regenerative experience for all involved. The core principle of regenerative tourism is to promote positive and lasting change in the places being visited [15,16]. This means that it is not just about reducing our impact but about actively working to restore and revitalize the host destinations. It requires a deep connection with the local community, a deep understanding of the natural and cultural systems that make a destination unique, and a willingness to work together to find solutions that work for everyone. One of the ways that regenerative tourism can do this is by supporting local economies [11,12]. By staying in locally-owned accommodations, eating at locally-owned restaurants, and buying locally-made products, travelers can help to create jobs and stimulate economic growth in the communities they visit [15,16]. Additionally, regenerative tourism often involves supporting local conservation initiatives, such as planting trees, supporting wildlife conservation programs, and supporting community-based sustainable agriculture initiatives [13,14].

Regenerative tourism also involves protecting and preserving cultural heritage. This can involve working with local communities to preserve traditional cultural practices, such as dance, music, and storytelling, and supporting cultural conservation initiatives, such as restoring historic buildings and preserving traditional landscapes [15,16]. Moreover, regenerative tourism also fosters learning about and experiencing the local culture, such as by taking a cooking class, visiting a local market, or participating in a local festival [11,12]. Finally, regenerative tourism involves respecting and valuing the natural environment. This means minimizing the impact on ecosystems and wildlife, such as by reducing waste and minimizing energy usage, and supporting conservation initiatives, such as supporting wildlife rehabilitation centers and national parks [10,12]. Furthermore, regenerative tourism can involve unique experiences of the natural beauty of a destination, such as hiking in a national park, kayaking in a scenic river, or exploring a beautiful beach [13,14]. Regenerative tourism is a people-centered holistic approach to travel that seeks to create positive and long-lasting change for local communities and the environment at the host destinations. It is about supporting local economies, protecting cultural heritage, and valuing the natural environment. By embracing regenerative tourism, travelers can play an active role in shaping a more sustainable and equitable world, one experience at a time [11,12].

Regenerative tourism can be seen as a response to some of the negative impacts of tourism identified in Gunn’s Tourism System [10,11,25]. While Gunn’s model emphasizes the potential for tourism to cause environmental and social harm over time, regenerative tourism seeks to minimize these impacts and even generate positive outcomes for the destination and its residents [12,25]. Specifically, regenerative tourism focuses on restoring and enhancing the natural and cultural environment of a destination rather than just mitigating negative impacts. It emphasizes local community involvement and benefits, and it seeks to create a more sustainable tourism industry overall [10,12]. Therefore, while Gunn’s Tourism System provides a framework for understanding the impacts of tourism on a destination, regenerative tourism is a specific approach to tourism development that seeks to create positive impacts and regenerate the environment and communities affected by tourism [10,13,25].

Trust is a critical factor that influences the behavior of tourists when it comes to choosing a regenerative tourism destination [16,26]. As environmental and social issues are becoming increasingly important, tourists are seeking destinations that demonstrate a commitment to sustainability, authenticity, and responsibility. Trust is built through the transparent communication of a destination’s practices, initiatives, and impacts on the environment and local communities [15,26]. This communication can include information about responsible waste management, conservation efforts, cultural preservation, and community involvement in regenerative tourism activities [12,26]. Tourists who trust a regenerative tourism destination are more likely to choose that destination over others. They are also more likely to recommend the destination to others, increasing the destination’s visibility and desirability. Therefore, trust can play a crucial role in repeat visitation, as tourists who have had a positive experience with a regenerative tourism destination are more likely to revisit it in the future [13,26]. This implies that a regenerative tourism destination can be successful if and when it prioritizes building trust with tourists through the transparent communication of its practices and initiatives. Eventually, this trust can lead to increased visitation and repeat visitation, benefiting both the destination and the tourists who seek regenerative tourism experiences [12,26].

Lastly, the tourism carrying capacity (i.e., the maximum number of tourists that a destination can accommodate without causing negative impacts on the environment, local community, and cultural heritage) can efficiently mobilize regenerative tourism practices [10,27]. By managing the destination’s carrying capacity, regenerative tourism can ensure that the number of tourists visiting the destination is sustainable, and the local resources can be replenished and regenerated, leading to a long-term positive impact on the environment and the community [12,27]. Hence, managing a destination’s carrying capacity is a crucial step toward implementing regenerative tourism practices [11,14,27].

2.3. Tourism Destination Competitiveness

A competitive tourism destination is one that has a strong brand and well-developed tourism infrastructure, including accommodations, transportation, attractions, and visitor services [19,20,28]. It is a destination that provides visitors with a memorable and authentic experience and that is accessible and easy to navigate. Tourism destination competitiveness refers to the ability of a destination to attract and retain tourists and generate economic benefits from their visits [17,18]. It is a measure of the effectiveness of a destination in providing a quality experience to visitors and in leveraging the benefits of tourism for local communities. Tourism competitiveness is influenced by a wide range of factors, including economic, environmental, cultural, and institutional conditions. Economic conditions refer to the availability of resources, such as investment capital, labor, and technology, which support tourism development [29,30]. Environmental conditions refer to the quality of the natural environment, including the presence of scenic areas, wildlife, and other attractions. Cultural conditions refer to the social, historical, and cultural heritage of the destination, as well as its customs and traditions. Institutional conditions refer to the policies, regulations, and programs that are in place to support tourism development. One of the most important factors affecting tourism competitiveness is the quality of the experience that visitors have at a destination [31,32]. This includes factors such as the level of service and hospitality offered by hotels, restaurants, and attractions, as well as the quality of visitor experiences, such as tours and activities [33,34].

A destination with high-quality visitor experiences is more likely to attract repeat visitors and generate positive word-of-mouth recommendations, which can help to build the destination’s reputation and increase its competitiveness [17,18]. Another key factor that affects tourism competitiveness is accessibility. A destination that is easily accessible by air, sea, or road, and that offers convenient and affordable transportation options for visitors, is more likely to attract tourists. This includes destinations with well-developed transportation systems, such as airports, seaports, and highways, as well as those that offer public transportation options, such as buses, trains, and taxis. In addition to these factors, the safety and security of a destination are also important considerations for tourists [17,28]. Destinations that are perceived as safe and secure are more likely to attract visitors and retain their business over time. This includes destinations with well-established emergency services and response systems, as well as those with well-trained law enforcement and security personnel [19,20]. Finally, the availability of visitor information and support services is also critical for a destination’s competitiveness. This includes visitor centers, tourism boards, and other resources that provide information about local attractions, activities, and events, as well as those that provide advice and support to visitors during their stay [30,31]. Destinations that offer comprehensive visitor information and support services are more likely to attract and retain tourists and generate positive economic benefits from their visits [17,18]. Tourism destination competitiveness is a complex and multifaceted concept that is influenced by a wide range of factors, including the quality of the experience that visitors have at a destination; its accessibility, safety, and security; and the availability of visitor information and support services. A competitive tourism destination is one that provides visitors with a memorable and authentic experience and that leverages the benefits of tourism for local communities [19,20].

2.4. Influencer Marketing

Influencer marketing can take many forms, from sponsored posts and product reviews to sponsored events and social media takeovers [35,36]. The goal is to create authentic, organic content that resonates with the influencer’s audience and helps build trust in the brand [23,37]. Influencer marketing is a form of digital marketing that leverages the influence of individuals with a large following on social media platforms to promote a brand, product, or service [21,22]. It involves partnering with social media influencers who have a large and engaged audience in a particular niche or industry. The idea behind influencer marketing is that people trust recommendations from individuals they follow and admire rather than from brands themselves. By partnering with influencers, brands can tap into their existing audience and reach new potential customers who are interested in the niche or industry the influencer covers [35,36]. One of the key benefits of influencer marketing is the ability to reach a targeted audience. Social media influencers typically have a specific niche or industry they focus on, and their followers are often highly interested in that area. By partnering with the right influencer, brands can reach potential customers who are already interested in their products or services [38,39].

Influencer marketing is also highly effective because it often feels more authentic and trustworthy than traditional advertising [40,41]. Social media influencers are seen as experts in their fields, and their followers trust their opinions and recommendations. When an influencer partners with a brand, they are effectively endorsing that brand, and their followers are more likely to trust and consider the brand as a result [21,22]. Another benefit of influencer marketing is that it can help build brand awareness and loyalty. By working with influencers, brands can reach a wider audience and establish a stronger online presence. When done correctly, influencer marketing can help build a strong, loyal community around a brand and increase customer engagement and retention [38,39,40]. Influencer marketing is also highly flexible and can be tailored to meet the specific needs of a brand or campaign. Brands can work with influencers on a one-off basis, or they can establish long-term partnerships. They can also choose to work with influencers who have a large or small following, depending on their marketing goals and budget [36,41]. However, it is important to remember that influencer marketing should be executed with care and transparency. Brands must be transparent about their partnership with influencers and disclose any sponsored content to their audience [21,22]. They must also ensure that the influencer’s content aligns with their brand values and messaging. Influencer marketing is a powerful tool for reaching a targeted audience and building brand awareness and loyalty [22,35]. By partnering with the right influencer, brands can reach new potential customers and establish a strong online presence. When executed correctly, influencer marketing can help brands build a loyal community and drive long-term business growth [38,39,40].

2.5. Net-Zero Commitment Concern and Regenerative Tourism Intention

The global concern for a net-zero commitment is driving the growth of regenerative tourism intention [3,11], as travelers seek to align their values with their travel decisions [3,13]. This trend is driven by the growing awareness of the need to reduce carbon emissions and the impact of human activities on the environment [16]. As interpreted by the theory of planned behavior, travelers are looking for options that not only minimize the impact on the environment but also contribute to its restoration and regeneration [42,43]. The increase in net-zero commitment concern has resulted in an increased demand for eco-friendly travel options, such as eco-lodges, green accommodations, and sustainable travel experiences [5,12]. Travelers are also more likely to support local communities and engage in activities that promote sustainable development [16]. This shift in consumer behavior is encouraging tourism operators to adopt more sustainable practices, such as reducing carbon emissions, using renewable energy sources, and promoting sustainable waste management practices [3,13].

The net-zero commitment concern is also affecting the travel industry as a whole, with many travel companies adopting more sustainable practices and incorporating environmental responsibility into their brand identity [4,16]. The quality of air and water, as well as the sustainable use of water resources, are essential components of achieving net zero and regenerative tourism [3,13]. Without the proper management and conservation of these resources, the tourism industry risks degrading the natural environment that visitors come to enjoy while also exacerbating climate change through increased carbon emissions [3,11]. By prioritizing the preservation of the air and water quality, and promoting sustainable water use practices, the tourism industry can move toward a more regenerative and responsible model that benefits both the environment and the local communities it serves [5,12].

The growth of eco-tourism and sustainable tourism has become increasingly popular among travelers looking to make a positive impact on the environment [16,24]. This trend is encouraging the tourism industry to adopt more sustainable practices and promoting the growth of eco-friendly and sustainable tourism [3,13]. As postulated by resilience theory, the travel industry continues to evolve, and it is important for organizations to prioritize environmental responsibility and promote sustainable development [44,45,46]. This will not only benefit the environment but also provide positive experiences for travelers and local communities. Hence, the first hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Net-zero commitment concern has a significantly positive effect on regenerative tourism intention.

2.6. Moderating Effects of Destination Competitiveness

In global tourism, destination competitiveness (DC) and tourism intention are two concepts that are intricately linked with each other [12,17,28,47]. DC refers to the ability of a destination to attract and retain tourists, while regenerative tourism intention (RTI) is the motivation of travelers to engage in activities that promote the conservation and preservation of the environment and local communities [11,28]. The effects of DC on RTI are complex and far-reaching, influencing both the tourism industry and the natural and cultural environment [14,29]. One of the most significant effects of DC on RTI is the development of sustainable tourism practices. Destinations with high levels of competitiveness are more likely to adopt sustainable practices that minimize the impact of tourism on the environment and local communities [12,17,48]. For example, these destinations may promote eco-friendly transportation options, use renewable energy sources, and encourage waste reduction and recycling. This creates a more sustainable and environmentally friendly destination, which in turn appeals to travelers who are motivated to engage in RTI [12,17,28]. Another effect of DC on RTI is the development of responsible tourism. Destinations that are competitive are more likely to engage in practices that benefit both the local economy and environment [28,49]. For example, they may invest in local suppliers and promote community-based tourism activities that allow travelers to experience the local culture and contribute to its preservation. This not only benefits the local community but also appeals to travelers who are motivated to engage in RTI [14,28].

DC also affects RTI by shaping travelers’ perceptions of a destination. Game theory (i.e., mathematical framework) can be used to understand the behavior of different stakeholders in the context of regenerative tourism [14,50]. Game theory provides a way to model the interactions between actors and their decisions, which can help identify potential conflicts and opportunities for cooperation toward regenerative tourism goals [11,28,50]. Game theory can help analyze how tourists, local communities, businesses, and governments make decisions that affect the sustainability and resilience of the tourism industry [13,50]. It can help identify situations where different stakeholders may have conflicting interests or incentives and suggest strategies for aligning these interests toward sustainable outcomes [10,18,50]. As illustrated by game theory, destinations that are highly competitive are often marketed as offering unique experiences and attractions, and this marketing can impact travelers’ expectations and motivation to engage in RTI [20,50,51]. For example, a destination marketed as being environmentally friendly may attract travelers who are motivated to engage in RTI, while a destination marketed as being focused on entertainment and leisure may attract travelers who are less likely to engage in RTI [15,50].

Finally, DC also affects RTI through the development of tourism infrastructure [12,17,31]. Destinations that are competitive are more likely to have high-quality tourism infrastructure, which can support sustainable and responsible tourism practices [28,30]. For example, a destination with a well-developed transportation system may be better able to support eco-friendly transportation options and reduce the impact of tourism on the environment [11,28]. Additionally, well-developed infrastructure may provide more opportunities for travelers to engage in RTI, such as through guided tours, community-based activities, and cultural experiences [3,11,19]. The effects of DC on RTI are far-reaching and include the development of sustainable tourism practices, responsible tourism, the shaping of travelers’ perceptions, and the development of tourism infrastructure. By understanding these effects, destinations can better promote RTI and create a more sustainable and responsible tourism industry [14,28,29]. Hence, the second hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Destination competitiveness significantly and positively moderates the effects of the net-zero commitment concern on regenerative tourism intention.

2.7. Moderating Effects of Influencer Marketing

Influencer marketing is changing the digital marketing trajectory as it is being increasingly utilized to promote products and services to a large audience through social media influencers [13,22,37]. In recent years, the tourism industry has also begun to embrace influencer marketing to promote regenerative tourism. Regenerative tourism, also known as responsible tourism, is a form of sustainable tourism that aims to promote sustainable development, the conservation of natural resources, and positive local community impacts [16,23,36]. The effects of influencer marketing on regenerative tourism intention can be both positive and negative. As interpreted by social learning theory, one of the positive effects of influencer marketing on regenerative tourism intention is that it can help to increase public awareness of regenerative tourism [40,52,53]. Influencers have a large following on social media and can spread the message of regenerative tourism to a wider audience. This increased visibility can help to create a buzz about the benefits of regenerative tourism, such as promoting sustainability and supporting local communities [16,23]. By sharing their personal experiences and promoting regenerative tourism, influencers can inspire others to engage in this type of travel [13,22]. Another positive effect of influencer marketing on regenerative tourism intention is that it can help to build trust and credibility with the target audience [11,13,22]. Influencers are seen as trusted sources by their followers, and their endorsement of a product or service can have a significant impact on the target audience’s purchase decision. In the case of regenerative tourism, influencer marketing can help to build trust and credibility with potential travelers, as influencers can share their experiences and share the benefits of regenerative tourism in a more personal and relatable way [16,23,38].

However, there are also negative effects of influencer marketing on regenerative tourism intention. One of the main concerns is that influencer marketing can be seen as inauthentic or staged. Influencers are often paid to promote products or services, and their endorsement may not always be genuine [13,21,22]. This can lead to skepticism among their followers and erode the trust and credibility that influencer marketing aims to build. Additionally, the use of influencer marketing in the tourism industry can lead to the over-promotion and over-commercialization of regenerative tourism [11,21]. Influencers may not always be knowledgeable about the sustainable practices and principles of regenerative tourism, and their endorsement of regenerative tourism may not always align with the principles of responsible tourism [11,16,37]. This can lead to confusion among travelers and undermine the authenticity of regenerative tourism. The effects of influencer marketing on regenerative tourism intention are complex and multifaceted [13,22]. On the one hand, influencer marketing can help to increase public awareness and build trust and credibility with potential travelers. On the other hand, it can also lead to skepticism, over-promotion, and over-commercialization of regenerative tourism [16,22,37]. Therefore, it is important for the tourism industry to carefully consider the use of influencer marketing in promoting regenerative tourism and to ensure that the principles of responsible tourism are respected and upheld [11,16,21,23]. Hence, the third hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Influencer marketing significantly and positively moderates the effects of the net-zero commitment concern on regenerative tourism intention.

The proposed conceptual model of regenerative tourism intention, as predicted by the net-zero commitment concern, influencer marketing, and tourism destination competitiveness, is graphically presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of RTI.

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling and Procedure

The present study explored expat tourists’ intention who were interested in regenerative tourism based on their net-zero commitment concern. The present study’s population consisted of international expats tourists residing in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The minimum sample size was determined as N > 200 based on the recommendations of prominent studies [11,54,55,56]. The study data were collected through an online survey using popular social media platforms (e.g., Facebook and LinkedIn) during the period August 2022 to January 2023. The survey link was shared on dedicated expat groups on Facebook (e.g., Expats in UAE representing 20.2k members; Expats in Dubai representing 73.3K members; and UAE Expats representing 25.8K members). The survey employed two eliminating questions, including: (1) Are you living as an expat in UAE? and (2) Do you have prior travel experience to a tourism destination (other than your home country)? Any respondents who replied ‘No’ to either of the two questions were excluded from the survey. Moreover, the demographic profile of the respondents adequately reflected their frequency of vacation travel (before COVID-19), i.e., (1) Once or twice per year (18%); (2) 3 to 5 times per year (44%); 6 to 8 times a year (32%); and more than 9 times a year (6%) [11,57]. Moreover, the respondents also reported on the number of hotel nights of stay at a tourism destination, including (1) 1–5 nights (63%); (2) 6–10 nights (17%); (3) 11–15 (12%) nights; and (4) more than 15 nights (8%). The participants were adequately informed about the purpose of the study and asked for their voluntary participation. Importantly, informed consent was also obtained from all participants before starting the online survey. The survey was administered in English, and it took approximately 10-15 min to complete. All respondents were assured confidentiality and anonymity of their participation; they were also allowed to withdraw from the survey at any stage and time [11]. The survey instantly ended as soon as the respondent(s) entered the answer to the final question and was not allowed to return to the survey as the response editing option was disabled [11,49]. A valid email of the respondent(s) was required to complete the survey, which ultimately discouraged the submission of multiple responses by the same respondent [11,49]. The collected data (N = 540) were analyzed using descriptive statistics and partial least squares-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to test the research hypotheses and to explore the underlying relationships between net-zero commitment concern, destination competitiveness, and influencer marketing and regenerative tourism intention [54,55,56].

3.2. Measures

The present study employed a combination of adapted and newly developed scales (see Appendix A) to measure and test the relationships between net-zero commitment concern (NZCC), regenerative tourism intention (RTI), destination competitiveness (DC), and influencer marketing (IM). Firstly, net-zero commitment concern was measured through newly developed scale (NTCC, representing 8 items) based on prominent studies on net zero [1,3,5,6,7,8,24]. Secondly, the measures for regenerative tourism intention (RTI representing 7 items), destination competitiveness (DC representing 8 items), and influencer marketing (IM representing 7 items) were adapted from prior research that established the validity of these latent constructs [11,17,18,21,22]. All scales were pre-tested in pilot study (N = 70) after extensive review and feedback by industry practitioners (n = 2) and senior academics (n = 4). Reliability and validity estimations of all measures in the pilot testing stage were adequately validated. Hence, the collection of study data for the next stage (i.e., hypotheses testing) was accomplished in a timely manner.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

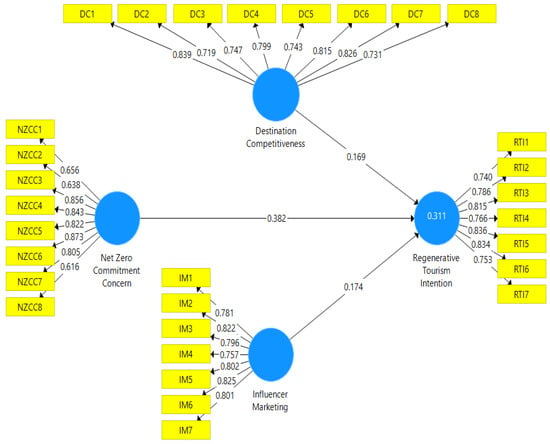

Using variance-based structural equation modeling (SEM) with Smart PLS version 3.3.5, the PLS-SEM-based measurement model (see Figure 2) estimations adequately established the scale reliabilities and validities for all measures of the latent constructs (i.e., NZCC, DC, IM, and RTI). The PLS-SEM estimation revealed that Cronbach’s Alpha (CA > 0.70), the composite reliability (CR > 0.70), and the average variance extracted (AVE > 0.50) were all much above the recommended levels (see Table 1). Moreover, the two leading approaches for the discriminant validity assessment (i.e., Fornell–Larcker approach and HTMT criterion) adequately established the discriminant validity for all the measures (i.e., HTMT values < 0.90; square root of AVE > inter-construct correlations) (see Table 2 and Table 3) [54,56].

Figure 2.

Measurement Model of RTI.

Table 1.

PLS Measurement Model Testing Estimations.

Table 2.

PLS Measurement Model—Fornell–Larcker Estimations.

Table 3.

PLS Measurement Model—HTMT Criterion Estimations.

4.2. Structural Model

The PLS-SEM-based structural model estimations using the bootstrapping procedure (500 subsamples) were employed to test the hypothesized relationships [58] between the net-zero commitment concern (NZCC) and regenerative tourism intention (RTI), as well as the moderating influence of destination competitiveness (DC) and influencer marketing (IM) on this relationship [54,55,56]. The PLS-SEM estimations revealed a statistical significance (t-vales > 0.64; p-values < 0.05) for all the hypothesized relationships (see Figure 3). The results highlighted that regenerative tourism intention (RTI) was significantly and positively influenced by the net-zero commitment concern (NZCC). Hence, the first hypothesis H1 (i.e., the effect of the net-zero commitment concern on regenerative tourism intention) was statistically accepted (see Table 4). Moreover, both destination competitiveness (DC) and influencer marketing (IM) adequately established a significant and positive moderating influence by strengthening the effects of the net-zero commitment concern on regenerative tourism intention [11]. Hence, both hypotheses H2 (i.e., the moderating influence of destination competitiveness) and H3 (i.e., the moderating influence of influencer marketing) were statistically accepted (see Table 4). Moreover, the model goodness of fit based on the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR = 0.074) and predictive relevance using Stone–Geisser’s Q2 (Q2 = 0.189) were above the recommended levels (SRMR < 0.080; Q2 > 0.10) [59]. Lastly, the PLS estimation for the coefficient for determination (R2 = 0.311) highlighted that the net-zero commitment concern (NZCC), destination competitiveness (DC), and influencer marketing (IM) adequately explained a variance of 31.1% in regenerative tourism intention (RTI) [54,55,56].

Figure 3.

Structural Model of RTI.

Table 4.

PLS Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing Estimations.

5. Discussion

The present study empirically examined the impact of net-zero commitment concern (NZCC) on regenerative tourism intention (RTI) and tested the moderating influence of destination competitiveness (DC) and influencer marketing (IM) on this relationship. The results showed that NZCC was positively related to RTI and that DC and IM played a significant role in enhancing the relationship between NZCC and RTI [1,3,12]. Studies have shown that environmental awareness, particularly concerning climate change, has become increasingly important to consumers and has impacted the way they make travel decisions [60,61]. The empirical evidence of this study supports this finding by demonstrating that NZCC had a significant positive effect on RTI. This suggests that consumers are more likely to engage in regenerative tourism activities if they are concerned about the impact of their travel on the environment [2,6,12,24]. The moderating effect of DC on the relationship between NZCC and RTI was also supported by the findings of this study [17]. According to the Destination Attractiveness Model (DAM), the competitiveness of a destination is a key factor in attracting tourists [17,61].

The present study’s finding highlighted that the relationship between NZCC and RTI was stronger in more competitive destinations. This suggests that destinations that invest in developing their competitiveness, such as through sustainable tourism practices, are more likely to attract tourists who are environmentally conscious [16,18,19]. Similarly, the study findings showed that IM had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between NZCC and RTI [13,21,22]. IM has been shown to be a powerful tool for promoting tourism destinations and experiences [60]. In this study, it was found that IM had a positive effect on RTI, particularly among consumers who are concerned about the environment. This suggests that destinations and tour operators that utilize influencer marketing strategies, particularly those that highlight their commitment to sustainability, are more likely to attract environmentally conscious tourists [11,22]. Several studies have explored the role of destination competitiveness and influencer marketing in promoting sustainable tourism [60,61]. The present study findings add to this literature by showing that both DC and IM play a significant role in enhancing the relationship between NZCC and RTI. This highlights the importance of investing in both destination competitiveness and influencer marketing for promoting regenerative tourism [11,37].

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The present study examined the net-zero commitment concern and its effects on regenerative tourism intention and the moderating influence of destination competitiveness and influencer marketing [5,12,17,21]. From a theoretical perspective, this research contributes to the body of knowledge on consumer behavior and the influence of environmental concerns on decision-making. It highlights the significance of the net-zero commitment concern in shaping consumer behavior toward regenerative tourism, which is essential in promoting sustainable tourism practices [7,10]. The current study provides valuable insights into net-zero commitments concerning the tourism industry and its future trajectory. This research sheds light on the importance of sustainability and the role of various factors in shaping consumer behavior toward eco-friendly tourism [62,63,64]. The research also highlights the role of destination competitiveness and influencer marketing in moderating the relationship between net-zero commitment concern and regenerative tourism intention. From a practical perspective, the findings of this research have significant implications for the tourism industry and its stakeholders. For policymakers and industry leaders, the research provides insights into the importance of incorporating sustainability into tourism practices and the role of destination competitiveness and influencer marketing in shaping consumer behavior [65]. This information can inform decision-making processes and help the industry shift toward more sustainable practices. Additionally, the research highlights the need for the tourism industry to take a proactive approach toward sustainability, including incorporating net-zero commitment concern into their marketing strategies and highlighting their efforts toward eco-friendly practices [13]. By doing so, they can appeal to consumers who prioritize sustainability and increase their destination competitiveness. The role of influencer marketing in shaping consumer behavior also highlights the importance of strategic marketing and the selection of appropriate influencers to promote regenerative tourism [14,15,22].

Furthermore, the present research findings provide insights into consumer behavior and their decision-making processes, which is valuable for tourism marketers in developing targeted marketing strategies [11,66]. By understanding the impact of the net-zero commitment concern on regenerative tourism intention and the moderating effects of destination competitiveness and influencer marketing, marketers can create campaigns that effectively appeal to consumers who prioritize sustainability [15,16,23,24]. The research highlights the importance of incorporating sustainability into tourism practices and the role of various factors in shaping consumer behavior [16,67]. The research also provides information that can guide decision-making processes and help the tourism industry shift toward more sustainable practices. Importantly, the research provides valuable insights into consumer behavior and their decision-making processes, which can inform marketing strategies and help increase destination competitiveness [15,16,24].

The global trend of regenerative tourism, driven by tourists’ net-zero commitment concern, has significant managerial implications for destinations seeking to enhance their competitiveness and reach a broader audience of environmentally conscious travelers through influencer marketing [1,5,10,17,22]. To remain competitive, destinations need to prioritize sustainability initiatives (e.g., renewable energy projects, reducing plastic waste, and promoting sustainable transportation options) [11,17,18]. Destinations can also collaborate with local communities to create regenerative tourism products and experiences that promote cultural exchange and support the local economy. Destinations can address tourists’ net-zero commitment concern by developing carbon offset programs and promoting eco-friendly practices, such as using locally sourced materials and reducing energy consumption [5,12,19]. The use of influencer marketing can play a crucial role in promoting regenerative tourism by partnering with social media influencers who have a strong following of environmentally conscious travelers [15,21]. Destinations that showcase regenerative tourism initiatives can encourage visitors to make a positive impact on the destination [11].

Regenerative tourism also poses new challenges and opportunities for destination managers [10,16]. One challenge is the need to balance environmental and social sustainability with economic viability. While regenerative tourism practices can have positive environmental and social impacts, they can also be costly to implement and may not be financially sustainable in the long term [10,13]. Destinations need to find innovative solutions to balance sustainability and profitability, such as creating public–private partnerships or accessing funding from international organizations [11,12]. Another managerial implication for regenerative tourism destinations is the potential to increase visitor satisfaction and loyalty. By providing unique and authentic tourism experiences that are environmentally and socially responsible, destinations can differentiate themselves from competitors and build brand loyalty among tourists [13,14]. Additionally, by collaborating with local communities to create regenerative tourism products, destinations can contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage and promote cultural exchange, further enhancing visitor satisfaction [10,12]. By addressing these managerial challenges and opportunities, destinations can position themselves as leaders in regenerative tourism to attract a rapidly growing segment of global travelers who value regenerative tourism practices [10,11,12].

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

While this study attempted to explore a new area of research, it was not without limitations. Firstly, this study was limited by its sample size (N = 540), as only participants from a specific region were included in the study. This may limit the generalizability of the empirical evidence and study findings to other regions or countries. The sample was also self-selected, which may have introduced bias into the findings based on statistical estimations. Secondly, this study relied on self-reported measures, which may have been subject to social desirability bias, where participants may not have answered truthfully [11]. Moreover, this study only investigated the relationship between net-zero commitment concern (NZCC) on regenerative tourism intention (RTI) and the moderating effects of destination competitiveness (DC) and influencer marketing (IM). Further research could examine the mediating effects of other variables, such as environmental awareness, environmental concern, and environmental knowledge, on this relationship. Moreover, future research could also examine the differences in the relationship between NZCC and RTI for different types of tourists, such as eco-tourists, adventure tourists, and cultural tourists. Another limitation of this study was that the measures used to assess NZCC and RTI were new and untested and therefore may not have been reliable or valid. Furthermore, this study did not consider the effects of personal and demographic variables, such as age, gender, income, and education, which may also influence the relationship between NZCC, RTI, DC, and IM. Finally, this study only examined the moderating effects of DC and IM on the relationship between NZCC and RTI, and it did not examine the interaction effects of these variables. Future research could extend the current findings by examining the interaction effects of NZCC, RTI, DC, and IM on each other. The current study provides important insights into the relationship between NZCC, RTI, DC, and IM, but further research is needed to strengthen the findings and address the limitations of the present study. Future research could also consider incorporating other factors and exploring the interaction effects of those factors on the relationship between NZCC and RTI [11,12].

5.3. Conclusions

The present study makes a pioneering effort to explore a new area of cross-disciplinary research that unfolds the complex nexus between net-zero commitment concern, destination competitiveness, influencer marketing, and regenerative tourism intention [5,11,21]. In addition, the present study also examined the interaction effects of destination competitiveness and influencer marketing on the relationship between net-zero commitment concern and regenerative tourism intention [5,11,17,21]. The findings indicated that net-zero commitment concern is a significant predictor of regenerative tourism intention, and that destination competitiveness and influencer marketing can moderate this relationship [1,11,18,21]. Destination competitiveness appears to amplify the positive relationship between net-zero commitment concern and regenerative tourism intention, while influencer marketing also strengthens this relationship (NZCC → RTI) with a significant moderating effect [11,18,21,24]. The findings of this research have important implications for both tourism marketers and policymakers. For marketers, the present study findings highlight the importance of promoting a destination’s commitment to sustainability, especially in the context of regenerative tourism [11,68]. By doing so, they can encourage travelers to choose more sustainable travel options and ultimately contribute to the goal of a more sustainable and regenerative tourism industry [11,24].

For policymakers, the study findings emphasize the importance of supporting destination competitiveness in terms of sustainability and regenerative tourism initiatives [5,12,20,21]. By doing so, they can help to create a supportive environment for sustainable and regenerative tourism development, which can ultimately lead to greater sustainability in the tourism sector and benefit both the environment and local communities. In summary, this research has demonstrated the important role that net-zero commitment concern, destination competitiveness, and influencer marketing play in shaping regenerative tourism intention. Further research is needed to further explore these relationships and to understand the impact of other factors on regenerative tourism intention [5,11,18,21].

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was secured from all participants who had volunteered to participate in this academic research.

Data Availability Statement

The study data are available on special request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Scale Items of All Measures

Net-Zero Commitment Concern (NZCC, 8-items, NZCC1 to NZCC8)

- “I feel that it is extremely important to take concerted actions to reduce our carbon footprint”.

- “I feel actively involved in reducing my carbon footprint”.

- “I believe that everyone has a role to play in reducing the impact of climate change”.

- “I feel deeply committed to supporting the cause of Net Zero and decarbonization targets”.

- “I am very much concerned about the impact of climate change on our planet and future generations”.

- “I am fully aware of the implications and challenges of Net-Zero as the Global Climate Goal”.

- “I am willing to pay a premium for products and services that have a lower carbon footprint and are produced sustainably”.

- “I feel extremely worried when nations fall short of their Net Zero commitments”.

Influencer Marketing (IM, 7-items, IM1 to IM7)

- “I make my travel decisions based on the recommendation(s) of an influencer on social media”.

- “I frequently consume content related to tourism destinations from influencers on social media”.

- “I consider that the recommendations made by influencers on social media about tourism destinations are highly credible”.

- “I follow influencers on social media who frequently feature or recommend tourism destinations”.

- “I mostly book accommodation(s) or activities based on the recommendation of an influencer on social media”.

- “I trust the opinions of influencers on social media compared to other sources such as travel guides, tourism boards, or friends and family”.

- “I believe that influencers on social media affect my perceptions of a tourism destination and my willingness to visit”.

Destination Competitiveness (DC, 8-items, DC1 to DC8)

- “I always consider factors such as accessibility, transportation options, and overall connectivity when choosing a tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the quality of tourism infrastructure (e.g., hotels, restaurants, and entertainment options) when choosing a tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the availability and quality of natural and cultural attractions when choosing a tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the level of safety and security of a tourism destination when making travel plans”.

- “I always consider the level of environmental sustainability and responsibility reflected by a tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the availability and quality of tourist services (e.g., tour guides, tourism information centers, and tourist-friendly policies and regulations) when choosing a tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the availability and quality of digital technologies and online services (e.g., free Wi-Fi, online booking systems, and mobile applications) when choosing a tourism destination”.

- “I always consider the cost of travel, accommodation, and other tourism-related expenses when deciding on a tourism destination, and how it balances with quality and experience”.

Regenerative Tourism Intention (RTI, 7-items, RTI1 to RTI7)

As a tourist, I would like to…

- “Improve the social, economic and environmental conditions at the host destination”.

- “Enhance the natural and cultural environment at the host destination”.

- “Enrich the local communities at the host destination”.

- “Enhance the quality of life for local people and communities at the host destination”.

- “Participate in host destination activities that help in reversing climate change”.

- “Make the host destination a better place for both current and future generations”.

- “Leave the host destination as a place “better” than it was before”.

References

- Perdana, S.; Xexakis, G.; Koasidis, K.; Vielle, M.; Nikas, A.; Doukas, H.; Gambhir, A.; Anger-Kraavi, A.; May, E.; McWilliams, B.; et al. Expert perceptions of game-changing innovations towards net zero. Energy Strat. Rev. 2023, 45, 101022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuán, M.Á.; Morales, Á.; Zaragoza, A. Precast Concrete Pavements of High Albedo to Achieve the Net “Zero-Emissions” Commitments. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergero, C.; Gosnell, G.; Gielen, D.; Kang, S.; Bazilian, M.; Davis, S.J. Pathways to net-zero emissions from aviation. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, C.; Higham, I.; Narulla, H. Submission to the High-Level Expert Group on the Net-Zero Emissions Commitments of Non-State Entities; e London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Klaaßen, L.; Steffen, B. Meta-analysis on necessary investment shifts to reach net zero pathways in Europe. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2023, 13, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudde, P.; Oakes, J.; Cochrane, P.; Caldwell, N.; Bury, N. The role of UK local government in delivering on net zero carbon commitments: You’ve declared a Climate Emergency, so what’s the plan? Energy Policy 2021, 154, 112245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fankhauser, S.; Smith, S.M.; Allen, M.; Axelsson, K.; Hale, T.; Hepburn, C.; Kendall, J.M.; Khosla, R.; Lezaun, J.; Mitchell-Larson, E.; et al. The meaning of net zero and how to get it right. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelj, J.; Geden, O.; Cowie, A.; Reisinger, A. Net-zero emissions targets are vague: Three ways to fix. Nature 2021, 591, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olarewaju, T.; Dani, S.; Jabbar, A. A Comprehensive Model for Developing SME Net Zero Capability Incorporating Grey Literature. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4459. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, A.U.; Abbas, M.; Abbasi, F.A.; Khan, S. How Tourist Experience Quality, Perceived Price Reasonableness and Regenerative Tourism Involvement Influence Tourist Satisfaction: A study of Ha’il Region, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Aktan, M.; Agrusa, J.; Khwaja, M.G. Linking Regenerative Travel and Residents’ Support for Tourism Development in Kaua’i Island (Hawaii): Moderating-Mediating Effects of Travel-Shaming and Foreign Tourist Attractiveness. J. Travel Res. 2022, 62, 782–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellato, L.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Nygaard, C.A. Regenerative tourism: A conceptual framework leveraging theory and practice. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Kaur, J. Anchoring “tourism value” within a regenerative tourism paradigm–a government perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 30, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.; Sydnor, S.; Marshall, M.; Noakes, S. Ecotourism, regenerative tourism, and the circular economy: Emerging trends and ecotourism. Routledge Handb. Ecotourism 2021, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cave, J.; Dredge, D. Regenerative tourism needs diverse economic practices. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N.; Bakas, F.; de Castro, T.; Silva, S. Creative Tourism Development Models towards Sustainable and Regenerative Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Bessiere, J. The Relationships between Tourism Destination Competitiveness, Empowerment, and Supportive Actions for Tourism. Sustainability 2023, 15, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, S.; Tung, V.W.S. Measuring the valence and intensity of residents’ behaviors in host–tourist interactions: Implications for destination image and destination competitiveness. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luštický, M.; Štumpf, P. Leverage points of tourism destination competitiveness dynamics. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronjé, D.F.; du Plessis, E. A review on tourism destination competitiveness. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, S.; Belanche, D.; Fernández, A.; Flavián, M. Influencer marketing on TikTok: The effectiveness of humor and followers’ hedonic experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, T.C.; Ashill, N.J. # Sponsored-influencer marketing: Effects of the commercial orientation of influencer-created content on followers’ willingness to search for information. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 316–329. [Google Scholar]

- Farivar, S.; Wang, F. Effective influencer marketing: A social identity perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erb, T.; Perciasepe, B.; Radulovic, V.; Niland, M. Corporate Climate Commitments: The Trend Towards Net Zero. In Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 2985–3018. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, C. Tourism Planning; Crane Russack: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yang, X. Tourist trust toward a tourism destination: Scale development and validation. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 562–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Shen, L.; Wong, S.W.; Cheng, G.; Shu, T. A “load-carrier” perspective approach for assessing tourism resource carrying capacity. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Destination competitiveness and resident well-being. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 43, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.A.S.; Azevedo, P.S.; Martín, J.M.M.; Martín, J.A.R. Determinants of tourism destination competitiveness in the countries most visited by international tourists: Proposal of a synthetic index. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimbaljević, M.; Stankov, U.; Pavluković, V. Going beyond the traditional destination competitiveness–reflections on a smart destination in the current research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2472–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffi, G.; Cucculelli, M.; Masiero, L. Fostering tourism destination competitiveness in developing countries: The role of sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I. Destination competitiveness: An analysis of determinant attributes. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, M.J.; Newton, J. Tourism destination competitiveness: A quantitative approach. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, F.F.; Gu, F.F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.Z.; Palmatier, R.W. Influencer Marketing Effectiveness. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Han, S.H.; Lee, J. Impacts of influencer attributes on purchase intentions in social media influencer marketing: Mediating roles of characterizations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, A.S.; Chaudhry, H.; Srivastava, M.K. Trends in Influencer Marketing: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. J. Interact. Advert. 2022, 22, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrontis, D.; Makrides, A.; Christofi, M.; Thrassou, A. Social media influencer marketing: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenlein, M.; Anadol, E.; Farnsworth, T.; Hugo, H.; Hunichen, J.; Welte, D. Navigating the New Era of Influencer Marketing: How to be Successful on Instagram, TikTok, & Co. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2020, 63, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Muqaddam, A.; Ryu, E. Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2019, 37, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, F.F.; Gu, F.F.; Palmatier, R.W. Online influencer marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 226–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, K.A.; Sia, S.K. Theory of planned behavior in predicting the construction of eco-friendly houses. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022, 33, 938–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M. Literature Review of Net Zero and Resilience Research of the Urban Environment: A Citation Analysis Using Big Data. Energies 2019, 12, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, E.; Juhola, S. Adaptive climate change governance for urban resilience. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1234–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, I.; Anjam, M.; Zaman, U. Hell Is Empty, and All the Devils Are Here: Nexus between Toxic Leadership, Crisis Communication, and Resilience in COVID-19 Tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Raza, S.H.; Abbasi, S.; Aktan, M.; Farías, P. Sustainable or a butterfly effect in global tourism? Nexus of pandemic fatigue, COVID-19-branded destination safety, travel stimulus incentives, and post-pandemic revenge travel. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.M.; Oliveira, M.; Lopes, J.; Zaman, U. Networks, innovation and knowledge transfer in tourism industry: An empirical study of SMEs in Portugal. Social Sciences 2021, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktan, M.; Zaman, U.; Nawaz, S. Examining destinations’ personality and brand equity through the lens of expats: Moderating role of expat’s cultural intelligence. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCanio, S.J.; Fremstad, A. Game theory and climate diplomacy. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 85, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Zhu, J. Cooperative equilibrium of the China-US-EU climate game. Energy Strat. Rev. 2022, 39, 100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Le, L.H.; Hancer, M. Using social learning theory in examining YouTube viewers’ desire to imitate travel vloggers. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2021, 12, 512–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Moisescu, O.I.; Radomir, L. Structural model robustness checks in PLS-SEM. Tour. Econ. 2020, 26, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Barnes, S.J.; Abbasi, S.; Anjam, M.; Aktan, M.; Khwaja, M.G. The bridge at the end of the world: Linking Expat’s pandemic fatigue, travel FOMO, destination crisis marketing, and vaxication for “greatest of all trips”. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Florez-Perez, L.; Khwaja, M.G.; Abbasi, S.; Qureshi, M.G. Exploring the critical nexus between authoritarian leadership, project team member’s silence and multi-dimensional success in a state-owned mega construction project. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 873–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult GT, M.; Calantone, R.J. Common Beliefs and Reality about Partial Least Squares: Comments on Rönkkö & Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. Tourism Under Climate Change: Will Slow Travel Supersede Short Breaks? AMBIO 2011, 40, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.-P.; Dubois, G. Consumer behaviour and demand response of tourists to climate change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghello, S. Mapping tourist landscapes in pandemic times: a dwelling-in-motion perspective. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Kumari, K.; Kar, S. Short-term Forecasting of Air Passengers based on Hybrid Rough Set and Double Exponential Smoothing Models. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2019, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Li, R.Y.M.; Huang, X. Sustainable Mountain-Based Health and Wellness Tourist Destinations: The Interrelationships between Tourists’ Satisfaction, Behavioral Intentions, and Competitiveness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Li, R.Y.M. Tourist Satisfaction, Willingness to Revisit and Recommend, and Mountain Kangyang Tourism Spots Sustainability: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, B.; Neelis, I.; Heslinga, J.H. Don’t hate the players, hate the system!—The continuation of deep-rooted travel patterns in the face of shock events. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E. Regenerative Design of Archaeological Sites: A Pedagogical Approach to Boost Environmental Sustainability and Social Engagement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Tourism resilience in the ‘new normal’: Beyond jingle and jangle fallacies? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).