“Low-Hanging Fruits” against Food Waste and Their Status Quo in the Food Processing Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Food Processing Company and Responsibility

1.2. Aim of the Study

- RQ (i): What is the status quo in implementing recommendations against food waste and which recommendations are basic in food processing companies?

- RQ (ii): Which recommendations are the ‘low-hanging fruit’ that are highly effective and can be easily implemented in the food processing industry?

- RQ (iii): What do companies consider to be the benefits and barriers to implementing the recommendations?

2. Materials and Methods

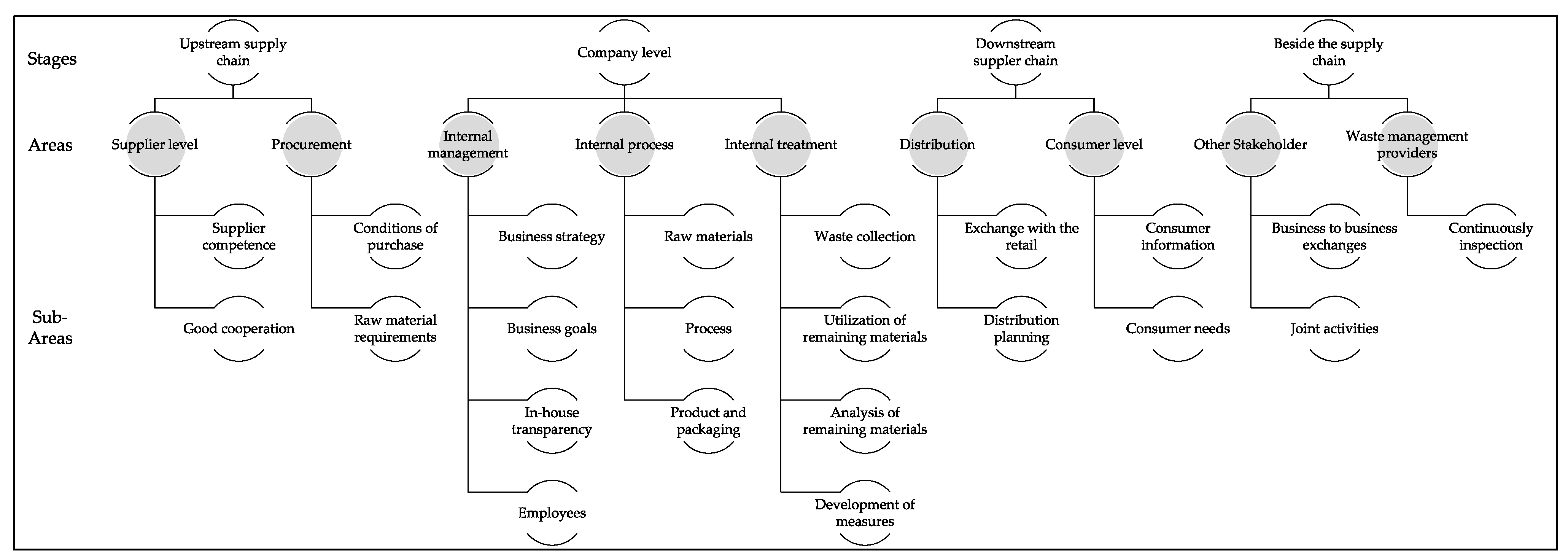

2.1. Development of the Questionnaire

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Samples

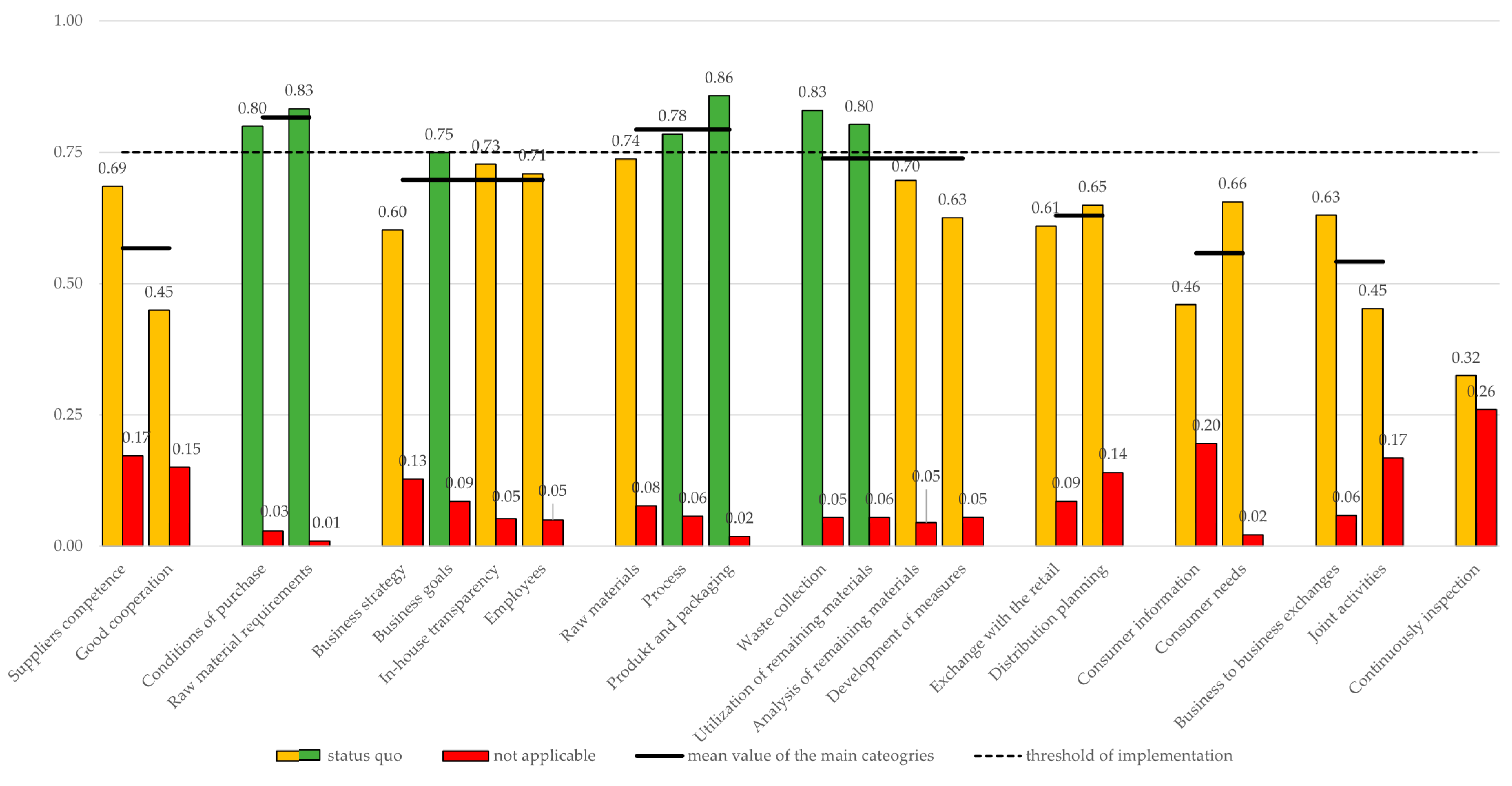

3.2. Status Quo of Implementation and Basic Recommendations

3.3. Assessment of Recommendations and ‘Low-Hanging Fruits’

3.4. Benefits and Barriers for Implementation of Recommendations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID | Recommendations | Sub-Areas | Average | Bakery and Farinaceous Products | Dairy Products and Eggs | Convenience Food | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQ * | Rank | SQ * | Rank | SQ * | Rank | SQ * | Rank | |||

| 1 | Establish a good practice | Suppliers competence | 0.588 | (43) | 0.545 | (48) | 0.833 | (21) | 0.500 | (44) |

| 2 | Conduct quality controls | Suppliers competence | 0.733 | (26) | 0.659 | (37) | 0.900 | (14) | 0.700 | (28) |

| 3 | Ensure proper storage and transport conditions | Suppliers competence | 0.735 | (25) | 0.700 | (32) | 0.917 | (10) | 0.792 | (18) |

| 4 | Conduct supplier waste audits and reviews | Good cooperation | 0.375 | (51) | 0.568 | (47) | 0.250 | (49) | 0.250 | (53) |

| 5 | Cooperate with suppliers | Good cooperation | 0.615 | (42) | 0.614 | (46) | 0.625 | (33) | 0.750 | (25) |

| 6 | Exchange best practice with suppliers | Good cooperation | 0.359 | (52) | 0.409 | (52) | 0.250 | (51) | 0.350 | (51) |

| 7 | Order the appropriate quantities | Conditions of purchase | 0.854 | (5) | 0.844 | (7) | 0.714 | (27) | 0.800 | (17) |

| 8 | Analyze raw material samples | Conditions of purchase | 0.745 | (20) | 0.813 | (12) | 0.607 | (34) | 0.700 | (29) |

| 9 | Order a quality level appropriate to a company’s own needs | Raw material requirements | 0.877 | (4) | 0.891 | (2) | 0.929 | (5) | 0.750 | (20) |

| 10 | Order raw material in appropriate product packaging | Raw material requirements | 0.788 | (12) | 0.800 | (14) | 0.857 | (17) | 0.800 | (16) |

| 11 | Develop a business strategy | Business strategy | 0.673 | (31) | 0.717 | (26) | 0.400 | (46) | 0.625 | (36) |

| 12 | Derive measures | Business strategy | 0.531 | (47) | 0.536 | (49) | 0.500 | (45) | 0.500 | (45) |

| 13 | Avoid food waste | Business goals | 0.638 | (37) | 0.714 | (28) | 0.550 | (38) | 0.667 | (34) |

| 14 | Adjust goals | Business goals | 0.785 | (13) | 0.731 | (24) | 0.833 | (20) | 0.688 | (31) |

| 15 | Ensure food safety | Business goals | 0.798 | (10) | 0.850 | (4) | 0.917 | (9) | 0.938 | (4) |

| 16 | Work within the legal requirements | Business goals | 0.783 | (15) | 0.733 | (23) | 1.000 | (3) | 0.813 | (14) |

| 17 | Inspire and act as a role model | Business goals | 0.744 | (21) | 0.731 | (25) | 0.900 | (13) | 0.542 | (43) |

| 18 | Develop and monitor key performance indicators | In-house transparency | 0.672 | (32) | 0.615 | (45) | 0.821 | (23) | 0.750 | (22) |

| 19 | Report activities | In-house transparency | 0.783 | (16) | 0.769 | (18) | 0.857 | (18) | 0.583 | (38) |

| 20 | Train employees | Employees | 0.878 | (3) | 0.846 | (5) | 0.821 | (22) | 0.875 | (9) |

| 21 | Ensure interdisciplinary collaboration | Employees | 0.625 | (39) | 0.673 | (36) | 0.571 | (37) | 0.700 | (30) |

| 22 | Put persons in charge | Employees | 0.625 | (40) | 0.692 | (34) | 0.643 | (30) | 0.458 | (47) |

| 23 | Analyze raw materials | Raw materials | 0.693 | (29) | 0.708 | (29) | 0.750 | (25) | 0.786 | (19) |

| 24 | Proper handling of raw materials | Raw materials | 0.781 | (17) | 0.833 | (8) | 0.833 | (19) | 0.857 | (10) |

| 25 | Ensure proper storage and transport conditions | Process | 0.740 | (23) | 0.646 | (40) | 0.875 | (16) | 0.875 | (8) |

| 26 | Plan the processing | Process | 0.807 | (9) | 0.771 | (17) | 1.000 | (2) | 0.821 | (13) |

| 27 | Establish a food loss rate and develop batch sizes | Process | 0.775 | (19) | 0.750 | (21) | 0.625 | (31) | 0.938 | (5) |

| 28 | Develop prevention strategies | Process | 0.816 | (7) | 0.733 | (22) | 0.667 | (29) | 1.000 | (1) |

| 29 | Ensure product quality | Product and packaging | 0.931 | (1) | 0.917 | (1) | 0.958 | (4) | 0.938 | (3) |

| 30 | Design packaging | Product and packaging | 0.784 | (14) | 0.846 | (6) | 0.667 | (28) | 0.750 | (24) |

| 31 | Collect and store remaining materials | Waste collection | 0.788 | (11) | 0.788 | (16) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.958 | (2) |

| 32 | Separate remaining materials | Waste collection | 0.814 | (8) | 0.808 | (13) | 0.929 | (7) | 0.833 | (11) |

| 33 | Ensure coordinated transport | Waste collection | 0.887 | (2) | 0.885 | (3) | 0.929 | (6) | 0.900 | (6) |

| 34 | Use the food waste hierarchy | Utilization of remaining materials | 0.779 | (18) | 0.769 | (19) | 0.929 | (8) | 0.750 | (21) |

| 35 | Chose the best way of utilization | Utilization of remaining materials | 0.827 | (6) | 0.827 | (9) | 0.893 | (15) | 0.800 | (15) |

| 36 | Analyze quantities | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.728 | (27) | 0.766 | (20) | 0.719 | (26) | 0.833 | (12) |

| 37 | Analyze the waste sources | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.737 | (24) | 0.817 | (11) | 0.594 | (35) | 0.708 | (26) |

| 38 | Assess the remaining materials | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.741 | (22) | 0.817 | (10) | 0.750 | (24) | 0.750 | (23) |

| 39 | Analyze alternative opportunities | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.656 | (34) | 0.700 | (33) | 0.594 | (36) | 0.583 | (39) |

| 40 | Analyze holistic products | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.617 | (41) | 0.625 | (44) | 0.528 | (42) | 0.607 | (37) |

| 41 | Develop measures | Development of measures | 0.660 | (33) | 0.706 | (30) | 0.528 | (41) | 0.679 | (33) |

| 42 | Prioritize measures | Development of measures | 0.647 | (36) | 0.703 | (31) | 0.625 | (32) | 0.571 | (41) |

| 43 | Evaluate measures | Development of measures | 0.569 | (45) | 0.717 | (27) | 0.525 | (43) | 0.375 | (50) |

| 44 | Coordinate with the retail | Exchange with the retail | 0.685 | (30) | 0.636 | (42) | 0.917 | (12) | 0.700 | (27) |

| 45 | Establish exchanges with the retail | Exchange with the retail | 0.534 | (46) | 0.636 | (43) | 0.542 | (40) | 0.375 | (49) |

| 46 | Control sales with marketing measures | Distribution planning | 0.579 | (44) | 0.659 | (39) | 0.550 | (39) | 0.625 | (35) |

| 47 | Ensure proper transport conditions | Distribution planning | 0.720 | (28) | 0.659 | (38) | 0.917 | (11) | 0.875 | (7) |

| 48 | Sensitize, consult and inform consumers | Consumer information | 0.459 | (49) | 0.472 | (50) | 0.250 | (50) | 0.500 | (46) |

| 49 | Identify the consumer needs | Consumer needs | 0.656 | (35) | 0.682 | (35) | 0.500 | (44) | 0.688 | (32) |

| 50 | Conduct business to business exchanges | Business to business exchanges | 0.630 | (38) | 0.795 | (15) | 0.219 | (52) | 0.563 | (42) |

| 51 | Collaborate with network partners | Joint activities | 0.388 | (50) | 0.455 | (51) | 0.143 | (53) | 0.583 | (40) |

| 52 | Conduct joint campaigns | Joint activities | 0.517 | (48) | 0.639 | (41) | 0.321 | (48) | 0.438 | (48) |

| 53 | Conduct continuous inspection | Continuous inspection | 0.324 | (53) | 0.393 | (53) | 0.375 | (47) | 0.250 | (52) |

| Recommendations | Sub-Areas | Average | Bakery and Farinaceous Products | Dairy Products and Eggs | Convenience Food | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF * | Rank | EF * | Rank | EF * | Rank | EF * | Rank | |||

| 1 | Establish a good practice | Suppliers competence | 0.680 | (39) | 0.670 | (43) | 0.781 | (21) | 0.792 | (18) |

| 2 | Conduct quality controls | Suppliers competence | 0.715 | (33) | 0.693 | (34) | 0.825 | (12) | 0.775 | (22) |

| 3 | Ensure proper storage and transport conditions | Suppliers competence | 0.771 | (19) | 0.705 | (28) | 0.958 | (2) | 0.796 | (17) |

| 4 | Conduct supplier waste audits and reviews | Good cooperation | 0.571 | (50) | 0.682 | (40) | 0.531 | (48) | 0.625 | (52) |

| 5 | Cooperate with suppliers | Good cooperation | 0.656 | (44) | 0.682 | (39) | 0.575 | (44) | 0.750 | (30) |

| 6 | Exchange best practice with suppliers | Good cooperation | 0.559 | (51) | 0.575 | (48) | 0.575 | (46) | 0.656 | (48) |

| 7 | Order the appropriate quantities | Conditions of purchase | 0.842 | (2) | 0.852 | (2) | 0.768 | (24) | 0.775 | (24) |

| 8 | Analyze raw material samples | Conditions of purchase | 0.773 | (17) | 0.789 | (14) | 0.786 | (20) | 0.775 | (23) |

| 9 | Order a quality level appropriate to a company’s own needs | Raw material requirements | 0.828 | (3) | 0.844 | (4) | 0.821 | (14) | 0.725 | (32) |

| 10 | Order raw material in appropriate product packaging | Raw material requirements | 0.792 | (13) | 0.842 | (5) | 0.821 | (13) | 0.750 | (27) |

| 11 | Develop a business strategy | Business strategy | 0.694 | (36) | 0.700 | (32) | 0.575 | (45) | 0.688 | (43) |

| 12 | Derive measures | Business strategy | 0.672 | (43) | 0.670 | (44) | 0.719 | (27) | 0.625 | (51) |

| 13 | Avoid food waste | Business goals | 0.677 | (41) | 0.696 | (33) | 0.625 | (41) | 0.708 | (35) |

| 14 | Adjust goals | Business goals | 0.744 | (26) | 0.654 | (46) | 0.792 | (19) | 0.688 | (42) |

| 15 | Ensure food safety | Business goals | 0.797 | (9) | 0.833 | (7) | 0.875 | (6) | 0.844 | (12) |

| 16 | Work within the legal requirements | Business goals | 0.747 | (23) | 0.708 | (27) | 0.833 | (11) | 0.750 | (26) |

| 17 | Inspire and act as a role model | Business goals | 0.721 | (30) | 0.692 | (36) | 0.775 | (23) | 0.675 | (46) |

| 18 | Develop and monitor key performance indicators | In-house transparency | 0.713 | (34) | 0.625 | (47) | 0.696 | (31) | 0.771 | (25) |

| 19 | Report activities | In-house transparency | 0.744 | (27) | 0.702 | (30) | 0.768 | (25) | 0.700 | (39) |

| 20 | Train employees | Employees | 0.744 | (28) | 0.702 | (31) | 0.679 | (36) | 0.863 | (7) |

| 21 | Ensure interdisciplinary collaboration | Employees | 0.685 | (38) | 0.673 | (42) | 0.583 | (43) | 0.875 | (6) |

| 22 | Put persons in charge | Employees | 0.719 | (32) | 0.710 | (26) | 0.661 | (40) | 0.700 | (41) |

| 23 | Analyze raw materials | Raw materials | 0.784 | (16) | 0.833 | (8) | 0.875 | (9) | 0.703 | (37) |

| 24 | Proper handling of raw materials | Raw materials | 0.804 | (7) | 0.818 | (10) | 0.896 | (4) | 0.813 | (14) |

| 25 | Ensure proper storage and transport conditions | Process | 0.770 | (20) | 0.664 | (45) | 0.792 | (17) | 0.859 | (8) |

| 26 | Plan the processing | Process | 0.785 | (14) | 0.688 | (37) | 0.896 | (5) | 0.857 | (9) |

| 27 | Establish a food loss rate and develop batch sizes | Process | 0.796 | (10) | 0.767 | (18) | 0.800 | (15) | 0.875 | (5) |

| 28 | Develop prevention strategies | Process | 0.800 | (8) | 0.758 | (20) | 0.688 | (33) | 0.958 | (2) |

| 29 | Ensure product quality | Product and packaging | 0.854 | (1) | 0.850 | (3) | 0.792 | (16) | 0.906 | (3) |

| 30 | Design packaging | Product and packaging | 0.811 | (6) | 0.839 | (6) | 0.688 | (32) | 0.958 | (1) |

| 31 | Collect and store remaining materials | Waste collection | 0.785 | (15) | 0.780 | (15) | 0.958 | (1) | 0.850 | (10) |

| 32 | Separate remaining materials | Waste collection | 0.794 | (11) | 0.808 | (12) | 0.857 | (10) | 0.775 | (21) |

| 33 | Ensure coordinated transport | Waste collection | 0.827 | (4) | 0.808 | (11) | 0.929 | (3) | 0.844 | (11) |

| 34 | Use the food waste hierarchy | Utilization of remaining materials | 0.792 | (12) | 0.792 | (13) | 0.875 | (8) | 0.813 | (16) |

| 35 | Chose the best way of utilization | Utilization of remaining materials | 0.826 | (5) | 0.861 | (1) | 0.875 | (7) | 0.813 | (15) |

| 36 | Analyze quantities | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.720 | (31) | 0.773 | (17) | 0.672 | (37) | 0.825 | (13) |

| 37 | Analyze the waste sources | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.752 | (22) | 0.767 | (19) | 0.703 | (29) | 0.750 | (28) |

| 38 | Assess the remaining materials | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.772 | (18) | 0.825 | (9) | 0.781 | (22) | 0.725 | (33) |

| 39 | Analyze alternative opportunities | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.721 | (29) | 0.777 | (16) | 0.719 | (26) | 0.700 | (40) |

| 40 | Analyze holistic products | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.676 | (42) | 0.680 | (41) | 0.688 | (34) | 0.661 | (47) |

| 41 | Develop measures | Development of measures | 0.746 | (25) | 0.735 | (21) | 0.703 | (30) | 0.714 | (34) |

| 42 | Prioritize measures | Development of measures | 0.709 | (35) | 0.727 | (22) | 0.681 | (35) | 0.638 | (49) |

| 43 | Evaluate measures | Development of measures | 0.686 | (37) | 0.719 | (24) | 0.667 | (39) | 0.575 | (53) |

| 44 | Coordinate with the retail | Exchange with the retail | 0.747 | (24) | 0.688 | (38) | 0.792 | (18) | 0.700 | (38) |

| 45 | Establish exchanges with the retail | Exchange with the retail | 0.651 | (45) | 0.716 | (25) | 0.667 | (38) | 0.638 | (50) |

| 46 | Control sales with marketing measures | Distribution planning | 0.622 | (47) | 0.705 | (29) | 0.563 | (47) | 0.781 | (20) |

| 47 | Ensure proper transport conditions | Distribution planning | 0.753 | (21) | 0.693 | (35) | 0.708 | (28) | 0.906 | (4) |

| 48 | Sensitize, consult and inform consumers | Consumer information | 0.603 | (48) | 0.500 | (52) | 0.500 | (50) | 0.688 | (45) |

| 49 | Identify the consumer needs | Consumer needs | 0.643 | (46) | 0.563 | (50) | 0.583 | (42) | 0.750 | (29) |

| 50 | Conduct business to business exchanges | Business to business exchanges | 0.679 | (40) | 0.725 | (23) | 0.500 | (49) | 0.688 | (44) |

| 51 | Collaborate with network partners | Joint activities | 0.547 | (52) | 0.525 | (51) | 0.446 | (52) | 0.708 | (36) |

| 52 | Conduct joint campaigns | Joint activities | 0.580 | (49) | 0.568 | (49) | 0.464 | (51) | 0.792 | (19) |

| 53 | Conduct continuous inspection | Continuous inspection | 0.464 | (53) | 0.413 | (53) | 0.417 | (53) | 0.750 | (31) |

References

- do Carmo Stangherlin, I.; de Barcellos, M.D. Drivers and barriers to food waste reduction. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2364–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Tracking Progress on Food and Agriculture-Related SDG Indicators 2021: A Report on the Indicators under FAO Custodianship; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-134967-0. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Food Waste Index Report 2021; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (BMEL). Nationale Strategie zur Reduzierung der Lebensmittelverschwendung; BMEL: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, B.; Bokelmann, W. Approaches of the German food industry for addressing the issue of food losses. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göbel, C.; Langen, N.; Blumenthal, A.; Teitscheid, P.; Ritter, G. Cutting food waste through cooperation along the food supply chain. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1429–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.; Schneider, F.; Leverenz, D.; Hafner, G. Baseline 2015 Thünen Report 71; Thünen Institute: Braunschweig, Germany, 2019; ISBN 9783865761989. [Google Scholar]

- Canali, M.; Amani, P.; Aramyan, L.; Gheoldus, M.; Moates, G.; Östergren, K.; Silvennoinen, K.; Waldron, K.; Vittuari, M. Food waste drivers in Europe, from identification to possible interventions. Sustainability 2017, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raak, N.; Symmank, C.; Zahn, S.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Rohm, H. Processing- and product-related causes for food waste and implications for the food supply chain. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF). Das Grosse Wegschmeissen. Available online: http://www.wwf.de/fileadmin/fm-wwf/Publikationen-PDF/WWF_Studie_Das_grosse_Wegschmeissen.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Rösler, F.; Kreyenschmidt, J.; Ritter, G. Recommendation of good practice in the food-processing industry for preventing and handling food loss and waste. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Melacini, A.; Perego, A.; Sert, S. Reducing food waste in food manufacturing companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipisinski, B. SDG Target 12.3 on Food Loss and Waste: 2022 Progress Report. Available online: https://champions123.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/22_WP_SDG%20Target%2012.3_2022ProgressReport_v3_0.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (BMEL). Grundsatzvereinbarung zur Reduzierung von Lebensmittelabfällen. Available online: https://www.bmel.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/_Ernaehrung/Lebensmittelverschwendung/grundsatzvereinbarung-lebensmittelverschwendung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Jepsen, D.; Vollmer, A.; Eberle, U.; Fels, J.; Schomerus, T. Entwicklung von Instrumenten zur Vermeidung von Lebensmittelabfällen; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stergren, K.; Gustavsson, J.; Bos-Brouwers, H.; Barbara, R. FUSIONS Definitional Framework for Food Waste; FUSIONS: Göteborg, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bortz, J.; Döring, N. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler, 5th ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; ISBN 9783540333050. [Google Scholar]

- Exxact New Media UG & Co. KG Firmen im Branchenverzeichnis Lebensmittelhersteller. Available online: https://www.branchenbuchdeutschland.de/branchenbuch/deutschland/lebensmittel (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Deutsche Industrie- und Handelskammer. EMAS-Register. Available online: https://www.emas-register.de/recherche?regnr=DE-&naceCodes=10-&erweitert=true (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken, 12th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015; ISBN 9783407257307. [Google Scholar]

- Jellil, A.; Woolley, E.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Rahimifard, S. A Manufacturing Approach to Reducing Consumer Food Waste. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 3, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, M.; Croad, T.; Vincent, T.; Mirosa, M. Critical Success Factors for Food Safety Management System. Towar. Safer Glob. Food Supply Chain 2022, 3, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strotmann, C.; Göbel, C.; Friedrich, S.; Kreyenschmidt, J.; Ritter, G.; Teitscheid, P. A participatory approach to minimizing food waste in the food industry-A manual for managers. Sustainability 2017, 9, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristóbal Garcia, J.; Vila, M.; Giavini, M.; Torres De Matos, C.; Manfredi, S. Prevention of Waste in the Circular Economy: Analysis of Strategies and Identification of Sustainable Targets—The Food Waste Example; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; Volume 28422, ISBN 978-92-79-65083-3. [Google Scholar]

- Borens, M.; Gatzer, S.; Magnin, C.; Timelin, B. Reducing Food Loss: What Grocery Retailers and Manufacturers Can Do. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/reducing-food-loss-what-grocery-retailers-and-manufacturers-can-do (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Bundesvereinigung der Deutschen Ernährungsindustrie (BVE). Verantwortlicher Umgang mit Ressourcen ist für die Ernährungsindustrie oberstes Gebot. Available online: https://www.bve-online.de/presse/pressemitteilungen/pm-110902 (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Bundesvereinigung der Deutschen Ernährungsindustrie (BVE). Antworten auf den steigenden Ertragsdruck in der Ernährungsindustrie. Available online: https://www.bve-online.de/presse/pressemitteilungen/pm-20160317 (accessed on 29 January 2023).

| Sample Characteristics | Sample Details | Total (n = 82) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-sectors | Bakery and Farinaceous Products | 21 | 25.6 |

| Dairy Products and Eggs | 12 | 14.6 | |

| Convenience Food | 9 | 11.0 | |

| Meat Products and Sausage | 7 | 8.5 | |

| Beverages | 7 | 8.5 | |

| Fruits and Vegetables | 6 | 7.3 | |

| Spices, Tea and Coffee | 6 | 7.3 | |

| Sugar and Confectionery | 4 | 4.9 | |

| Fish and Seafood Product | 2 | 2.4 | |

| Grains and Oilseeds | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Other Products | 7 | 8.5 | |

| Employees | Less than 100 | 27 | 33.3 |

| (n = 81) | 101–500 | 34 | 42.0 |

| 501–1000 | 12 | 14.8 | |

| More than 1000 | 8 | 9.9 | |

| Position of the respondents | Quality management | 27 | 32.9 |

| Company management | 17 | 20.7 | |

| Environment and sustainability | 11 | 13.4 | |

| Production | 9 | 11.0 | |

| Marketing | 9 | 11.0 | |

| Public relations and communication | 4 | 4.9 | |

| Other | 5 | 6.1 |

| Self-Assessment | Total (n = 82) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-assessment of dealing with food waste in the own company (before answering the questionnaire) | Excellent | 23 | 28 |

| Good | 40 | 48.8 | |

| Average | 14 | 17.1 | |

| Bad | 5 | 6.1 | |

| Terrible | 0 | 0 | |

| Self-assessment of dealing with food waste in the own company (after answering the questionnaire) | Excellent | 14 | 17.1 |

| Good | 39 | 47.6 | |

| Average | 26 | 31.7 | |

| Bad | 3 | 3.7 | |

| Terrible | 0 | 0 | |

| Impact of the Corona pandemic on food waste in the own company | A good deal better | 0 | 0 |

| Somewhat better | 10 | 12.2 | |

| No change | 65 | 79.3 | |

| Somewhat worse | 6 | 7.3 | |

| A good deal worse | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Will the topic of food waste reduction and prevention play a more important role in the future due to the current war in Ukraine? (n = 81) | Yes, it becomes more important | 42 | 51.9 |

| It has no influence | 29 | 35.8 | |

| No, other security of supply issues become more important | 10 | 12.3 | |

| ID | Recommendations | Sub-Areas | Average | Bakery and Farinaceous Products | Dairy Products and Eggs | Convenience Food | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SQ * | Rank | SQ * | Rank | SQ * | Rank | SQ * | Rank | |||

| 29 | Ensure product quality | Product and packaging | 0.93 | (1) | 0.92 | (1) | 0.96 | (4) | 0.94 | (3) |

| 33 | Ensure coordinated transport | Waste collection | 0.89 | (2) | 0.88 | (3) | 0.93 | (6) | 0.90 | (6) |

| 20 | Train employees | Employees | 0.88 | (3) | 0.85 | (5) | 0.82 | (22) | 0.88 | (9) |

| 9 | Order a quality level appropriate to a company’s own needs | Raw material requirements | 0.88 | (4) | 0.89 | (2) | 0.93 | (5) | 0.75 | (20) |

| 7 | Order the appropriate quantities | Conditions of purchase | 0.85 | (5) | 0.84 | (7) | 0.71 | (27) | 0.80 | (17) |

| 35 | Chose the best way of utilization | Utilization of remaining materials | 0.83 | (6) | 0.83 | (9) | 0.89 | (15) | 0.80 | (15) |

| 28 | Develop prevention strategies | Process | 0.82 | (7) | 0.73 | (22) | 0.67 | (29) | 1.00 | (1) |

| 32 | Separate remaining materials | Waste collection | 0.81 | (8) | 0.81 | (13) | 0.93 | (7) | 0.83 | (11) |

| 26 | Plan the processing | Process | 0.81 | (9) | 0.77 | (17) | 1.00 | (2) | 0.82 | (13) |

| 15 | Ensure food safety | Business goals | 0.80 | (10) | 0.85 | (4) | 0.92 | (9) | 0.94 | (4) |

| 10 | Order raw material in appropriate product packaging | Raw material requirements | 0.788 | (12) | 0.800 | (14) | 0.857 | (17) | 0.800 | (16) |

| 31 | Collect and store remaining materials | Waste collection | 0.788 | (11) | 0.788 | (16) | 1.000 | (1) | 0.958 | (2) |

| 14 | Adjust goals | Business goals | 0.785 | (13) | 0.731 | (24) | 0.833 | (20) | 0.688 | (31) |

| 30 | Design packaging | Product and packaging | 0.784 | (14) | 0.846 | (6) | 0.667 | (28) | 0.750 | (24) |

| 19 | Report activities | In-house transparency | 0.783 | (16) | 0.769 | (18) | 0.857 | (18) | 0.583 | (38) |

| 16 | Work within the legal requirements | Business goals | 0.783 | (15) | 0.733 | (23) | 1.000 | (3) | 0.813 | (14) |

| 24 | Proper handling of raw materials | Raw materials | 0.781 | (17) | 0.833 | (8) | 0.833 | (19) | 0.857 | (10) |

| 34 | Use the food waste hierarchy | Utilization of remaining materials | 0.779 | (18) | 0.769 | (19) | 0.929 | (8) | 0.750 | (21) |

| 27 | Establish a food loss rate and develop batch sizes | Process | 0.775 | (19) | 0.750 | (21) | 0.625 | (31) | 0.938 | (5) |

| ID | Recommendations | Sub-Areas | Average | Bakery and Farinaceous Products | Dairy Products and Eggs | Convenience Food | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF * | Rank | EF * | Rank | EF * | Rank | EF * | Rank | |||

| 29 | Ensure product quality | Product and packaging | 0.854 | (1) | 0.850 | (3) | 0.792 | (16) | 0.906 | (3) |

| 7 | Order the appropriate quantities | Conditions of purchase | 0.842 | (2) | 0.852 | (2) | 0.768 | (24) | 0.775 | (24) |

| 9 | Order a quality level appropriate to a company’s own needs | Raw material requirements | 0.828 | (3) | 0.844 | (4) | 0.821 | (14) | 0.725 | (32) |

| 33 | Ensure coordinated transport | Waste collection | 0.827 | (4) | 0.808 | (11) | 0.929 | (3) | 0.844 | (11) |

| 35 | Chose the best way of utilization | Utilization of remaining materials | 0.826 | (5) | 0.861 | (1) | 0.875 | (7) | 0.813 | (15) |

| 30 | Design packaging | Product and packaging | 0.811 | (6) | 0.839 | (6) | 0.688 | (32) | 0.958 | (1) |

| 24 | Proper handling of raw materials | Raw materials | 0.804 | (7) | 0.818 | (10) | 0.896 | (4) | 0.813 | (14) |

| 28 | Develop prevention strategies | Process | 0.800 | (8) | 0.758 | (20) | 0.688 | (33) | 0.958 | (2) |

| 15 | Ensure food safety | Business goals | 0.797 | (9) | 0.833 | (7) | 0.875 | (6) | 0.844 | (12) |

| 27 | Establish a food loss rate and develop batch sizes | Process | 0.796 | (10) | 0.767 | (18) | 0.800 | (15) | 0.875 | (5) |

| 32 | Separate remaining materials | Waste collection | 0.794 | (11) | 0.808 | (12) | 0.857 | (10) | 0.775 | (21) |

| 10 | Order raw material in appropriate product packaging | Raw material requirements | 0.792 | (13) | 0.842 | (5) | 0.821 | (13) | 0.750 | (27) |

| 34 | Use the food waste hierarchy | Utilization of remaining materials | 0.792 | (12) | 0.792 | (13) | 0.875 | (8) | 0.813 | (16) |

| 31 | Collect and store remaining materials | Waste collection | 0.785 | (15) | 0.780 | (15) | 0.958 | (1) | 0.850 | (10) |

| 26 | Plan the processing | Process | 0.785 | (14) | 0.688 | (37) | 0.896 | (5) | 0.857 | (9) |

| 23 | Analyze raw materials | Raw materials | 0.784 | (16) | 0.833 | (8) | 0.875 | (9) | 0.703 | (37) |

| 8 | Analyze raw material samples | Conditions of purchase | 0.773 | (17) | 0.789 | (14) | 0.786 | (20) | 0.775 | (23) |

| 38 | Assess the remaining materials | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.772 | (18) | 0.825 | (9) | 0.781 | (22) | 0.725 | (33) |

| 3 | Ensure proper storage and transport conditions | Suppliers competence | 0.771 | (19) | 0.705 | (28) | 0.958 | (2) | 0.796 | (17) |

| 25 | Ensure proper storage and transport conditions | Process | 0.770 | (20) | 0.664 | (45) | 0.792 | (17) | 0.859 | (8) |

| 47 | Ensure proper transport conditions | Distribution planning | 0.753 | (21) | 0.693 | (35) | 0.708 | (28) | 0.906 | (4) |

| 37 | Analyze the waste sources | Analysis of remaining materials | 0.752 | (22) | 0.767 | (19) | 0.703 | (29) | 0.750 | (28) |

| Benefits | Total (n = 110) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Conservation of resources | 34 | 30.9 |

| Cost savings | 23 | 20.9 |

| Company-specific measures | 11 | 10.0 |

| Sensitization | 9 | 8.2 |

| Systematic and holistic approach | 6 | 5.5 |

| More added value and higher profitability | 6 | 5.5 |

| Source of inspiration and decision support | 5 | 4.5 |

| Take on ethical responsibility | 5 | 4.5 |

| Process optimization | 5 | 4.5 |

| Collaboration | 3 | 2.7 |

| Image improvement | 2 | 1.8 |

| Fulfillment of the sustainability strategy | 1 | 0.9 |

| Barriers | Total (n = 110) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Customer requirements and acceptance | 14 | 12.7 |

| Cost and time intensive | 14 | 12.7 |

| Legal requirements | 12 | 10.9 |

| Personnel costs | 10 | 9.1 |

| Difficult implementation in day-to-day business | 9 | 8.2 |

| Employee acceptance and activation | 8 | 7.3 |

| Other priorities | 6 | 5.5 |

| Complexity of products and processes | 6 | 5.5 |

| Determination of responsibility | 4 | 3.6 |

| No knowledge about downstream and upstream supply chains | 4 | 3.6 |

| Supplier acceptance | 3 | 2.7 |

| Appropriate packaging | 3 | 2.7 |

| Sales fluctuations | 3 | 2.7 |

| Topic has not much attention | 3 | 2.7 |

| Others | 11 | 10.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rösler, F.; Kreyenschmidt, J.; Ritter, G. “Low-Hanging Fruits” against Food Waste and Their Status Quo in the Food Processing Industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065217

Rösler F, Kreyenschmidt J, Ritter G. “Low-Hanging Fruits” against Food Waste and Their Status Quo in the Food Processing Industry. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):5217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065217

Chicago/Turabian StyleRösler, Florian, Judith Kreyenschmidt, and Guido Ritter. 2023. "“Low-Hanging Fruits” against Food Waste and Their Status Quo in the Food Processing Industry" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 5217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065217

APA StyleRösler, F., Kreyenschmidt, J., & Ritter, G. (2023). “Low-Hanging Fruits” against Food Waste and Their Status Quo in the Food Processing Industry. Sustainability, 15(6), 5217. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065217