Abstract

The way corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication relates to corporate reputation has attracted an increasing amount of attention from communication and business researchers and practitioners. To place our study in the context of CSR and employee communication, we proposed a CSR communication—motives—organizational identification—corporate reputation model. Data collected from an online Qualtrics survey (n = 811) supported all the proposed hypotheses linking informativeness and factual tone in CSR communication, employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives of their organizations’ CSR activities, organizational identification, and corporate reputation. Specifically, informativeness and a factual tone in CSR communication were positively related to employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives of their organizations’ CSR activities. Employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives of their organizations’ CSR activities were positively associated with employee organizational identification. Employee organizational identification was positively related to corporate reputation. In addition, employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives of their organizations’ CSR activities and employee organizational identification turned out to be two significant mediators in the proposed model between CSR communication and corporate reputation. We conducted a two-step structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis to analyze the collected data. The theoretical and practical implications of the study were discussed.

1. Introduction

Stakeholders‘ interest in various organizations’ impact on environmental and social sustainability has been intensified due to surging environmental and social crises [1]. Engaging in pro-social undertakings has even evolved as “a strategic obligation and necessity” (p. 1, [2]). Analyses of the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and stakeholders have predominantly focused on external stakeholder groups, such as customers [3,4,5]. Consequently, the micro-level effects of CSR on employees’ attitudes and behaviors are underexplored. An apparent void lies in investigating the CSR perceptions and reactions from employees, who comprise a critical internal stakeholder [6,7,8]. Latif et al. [9] contended that “the employee-related perceptions to measure CSR initiatives have not been discussed in detail” (p. 1).

A shift of attention to the effects of employees’ CSR perceptions on their attitudes and behaviors has gradually emerged. Based on secondary data from an objective, third-party database, Rothenberg et al. [10] found that well-treated employees contributed to high CSR performance. This finding echoed their previous discovery [11] that employee engagement drives CSR performance. Their work underscored the need to conduct further empirical studies on the impact of employees’ perceptions of organizations’ CSR involvement. Recent studies have found CSR to be positively linked to several areas of employee attitude and behavior, such as commitment [12,13], perceived organizational support [14,15], job satisfaction [16,17] , and job performance [18,19]. Unfortunately, extant studies probing the organizational effects of CSR and employees are mostly organization-centric, neglecting employees’ interpretations regarding CSR communication. Aguinis and Glavas [20] explicitly noted that only 4% of the published CSR studies centered on the employee level of CSR outcomes. Employee perceptions about organizations’ involvement in CSR initiatives have a significant impact on employees’ attitudinal and behavioral outcomes [21]. Particularly when viewing CSR as a strategic practice, organizations do communicate intensively about their CSR practices [22,23]. Employees, however, have become increasingly suspicious about whether these practices actually contribute to the welfare of society and the environment [24]. Notably, recent research on CSR and employees demonstrates that employees care strongly about the underlying organizational motives for their employers’ CSR endeavors [25,26]. CSR activities serve as salient triggers for employees to assess the distinctiveness and attractiveness of their organizations [27,28]. Other scholars [21,29] emphasized that organizations’ actual CSR activities are not identical to employees’ CSR perceptions. Employee attitudes and behaviors are driven by their assessment of their organizations’ motives behind CSR programs [17,30]. Therefore, taking an employee-centric view to understand the way that employees assess their organizations’ CSR activities is paramount to elucidating the micro and organizational impact of these perceptual judgments on employees [24].

To bridge this significant gap regarding employee-centric research on CSR impact, this study adopted attribution theory [31] to explain employees’ subjective interpretations of their organizations’ CSR-induced motives. Based on attribution theory, stakeholders tend to care less about what organizations do than about why they do it [32]. The causes behind CSR activities seem much more intriguing than the activities themselves [33,34]. The above two reasons underscore the attributional processes that are likely to occur among employees when being exposed to CSR-related communication.

Although the role of CSR communication has been widely acknowledged, there is still a lack of research on what dimensions constitute effective CSR communication [35,36]. Schaefer et al. [17] lamented that what is “clearly under-researched is the role played by a company’s CSR communication […] in employees’ evaluation of CSR” (p. 192). Communication professionals are oftentimes left perplexed on exactly how to design communication programs to avoid stakeholders’ skepticism and resistance toward CSR and CSR communication [37,38,39]. Since a key focus of this study lies in examining employees’ interpretations of organizational CSR initiatives, it is reasonable to link specific communication factors with employees’ CSR perceptual assessment. In particular, two fundamental communication factors identified by [35]—message content and tone—are chosen as antecedents of employee CSR attribution. Findings from related studies [24,25] suggest that only the perceived other-serving or genuine motives, compared to self-serving motives, result in desirable employee outcomes. This study thus seeks to examine the impact of two crucial communication factors on employee-perceived other-serving or intrinsic CSR motives.

Informed by recent studies’ findings that CSR provides a crucial source of identification for employees [40,41,42], this study explored how CSR communication affected employee organizational identification through the mediation of perceived intrinsic CSR motives. This link further revealed the mechanism of how and why CSR communication influenced employees’ organizational identification. Echoing the recent shift in CSR research [43,44] to explore employee-centered outcomes and a growing attention to the impact of CSR attributions in those relationships [21,24,45], this study specifically examined: (1) how two central CSR communication factors (informativeness and factual tone) contributed to employees’ cognitive assessments of their employers’ CSR motives; (2) how the perceived CSR motives affected employee organizational identification and mediated the relationship between CSR communication and employee organizational identification; and (3) how employee identification affected their perceptual judgment of their employers’ corporate reputation and mediated the influence of perceived CSR motives on corporation reputation assessment.

This study presents significant implications for both research and practice. First, identifying and confirming the specific communication dimensions that contribute to effective CSR communication, grounded in employees’ perceptions, is conducive to illustrating the underlying mechanism of how and why CSR communication is pivotal to an organization’s CSR endeavors. Second, the findings from this study have heuristic value in enriching the existing CSR communication theories that link communication factors to employee-level perceptual and behavioral outcomes in the context of CSR practice. Lastly, understanding the mechanisms of employees’ CSR attribution and organizational identification enables CSR communication managers to design and manage their CSR communication programs with more precision, optimizing the value of CSR practice for both employees and other intended beneficiaries.

2. Literature Review

2.1. CSR Communication

CSR communication refers to an organization’s “communication to internal and external stakeholders about its contribution to society, the environment and economic development” ([46], p. 484). Many studies have established a strong link between promoting positive social change and strategic organizational outcomes, such as corporate reputation and financial performance [47,48]. Communicating about an organization’s CSR performance, however, does not warrant effective CSR communication because the contributing factors for effective CSR communication are different from those for CSR performance [49]. Communication scholars [35,39,50,51] have strongly cautioned their readers about the mounting suspicion of stakeholders regarding organizations’ CSR motives when those organizations aggressively promote their CSR activities, resulting in a CSR communication dilemma. Several studies [34,52,53] found that skepticism regarding CSR motives appears to be the most significant predictor of negative responses to CSR. Therefore, a pressing challenge in CSR communication is how to attenuate stakeholder skepticism and identify those communication factors that can foster stakeholders’ perceptions of organizations’ CSR motives as authentic and genuine [39,54].

The existing literature has identified several key dimensions for effective CSR communication, including the use of narratives [39] , message transparency and relevance [49], value-based framing [23], message informativeness [34], objective and outcome-focused messages [51], message authenticity [55], and message tone [35]. Stakeholders (e.g., customers) adopt different sense-making and reasoning processes to interpret and understand organizational messages (e.g., CSR communication) [51]. It is, thus, vital for organizations to strategize not only what to say but also how to express CSR-related messages. Among these identified communication factors, message content (i.e., what to communicate) and message tone (self-promotional vs. factual tone) are significantly related to stakeholder awareness of an organization’s CSR activities [47]. In return, such CSR awareness influences how stakeholders make sense of the motives driving an organization’s CSR initiatives [32]. In alignment with these previous findings, this study thus focuses on message content and message tone (particularly, factual tone) as precursors of employees’ perceptual judgments of organizations’ CSR motives.

2.1.1. Message Content: CSR Informativeness

Effective CSR communication requires organizations to adequately educate stakeholders about the targeted social issues (e.g., reasons as to why organizations need to commit to a particular social issue), as well as informing stakeholders of their organizational involvement with the specific social issues [23,35]. Du et al. [56] identified a comprehensive framework of CSR communication with four key content factors in CSR communication, namely, CSR commitment, impact, motives, and fit. To convey CSR commitment, an organization can focus on communicating the number of donations, the consistency of donations, and the continuity of commitment. CSR’s impact addresses the social outcomes or the actual benefits of a particular social cause. By communicating CSR commitment and its social impact, organizations provide cognitive cues for stakeholders to assess the organizations’ CSR motives [57]. Since a dominant challenge in CSR communication lies in mitigating stakeholders’ skepticism [39], it is essential for an organization to explain frankly why it advocates for a social issue, how its CSR initiatives are benefiting both society and the organization itself, other CSR beneficiaries’ information, and whether third-party endorsement is present [47,58]. Lastly, CSR’s fit in terms of message content deals with the perceived congruence between an organization’s CSR endeavors and its business expertise. This perceived fit influences stakeholders’ CSR attributions, in that stakeholders are likely to identify an organization’s CSR initiatives as being driven by self-interest when perceiving a low level of meaningful connection between a social cause and an organization’s identity or core business [17,32,59]. When an organization’s CSR activities do not fit with its business, it should increase the perceived CSR fit by discussing the rationale behind its social initiatives [56]. Building on these dimensions, Kim and Ferguson [35] defined the informativeness of CSR communication as “information that should be conveyed in CSR communication regarding a company’s CSR efforts themselves, such as its CSR commitment […] impact, motives, and fit” (p. 553).

The utility and value of adopting these major content factors in CSR communication have been consistently validated in recent studies [17,49]. Kang and Atkinson [51] confirmed the positive impact of objective and outcome-focused messages (i.e., the dimension of impact) on reducing hotel consumers’ skepticism toward CSR. Studies from Dalla-Pria and Rodríguez-deDios [60] and Schade et al. [32] affirmed that framing CSR communication in value-driven or public-serving motives (organizations’ willingness to affect society positively) (i.e., the dimension of intrinsic motives) compared to egotistic motives evoked more positive behavioral (e.g., positive word of mouth) and attitudinal (e.g., consumer attitudes) outcomes from stakeholders.

2.1.2. Message Tone: CSR Factual Tone

Message tone in CSR communication has a considerable influence on the level of trust that stakeholders have in an organization’s CSR motives. In particular, stakeholders are highly likely to interpret a self-promotional tone in CSR communication as evidence of their being driven by self-interest [49]. As a result, stakeholders may deem an organization’s CSR endeavors to be hypocritical attempts to increase profits and, hence, develop negative responses toward the target organization [39,47,61]. Rather, the tone of CSR communication should be factual, honestly representing what an organization has done to support a social cause and frankly acknowledging how these CSR activities are beneficial to society and to the organization itself [32,62]. Kim [49] thus defined “factual message tone in CSR communication” as “a factual quality and feeling expressed in CSR communication” (p. 1146).

2.2. CSR Motive Perception

Due to the paradox between the nature of a for-profit organization’s pursuit of profits and the nature of CSR seeking to enhance societal welfare, stakeholders are unsurprisingly skeptical of organizations’ CSR endeavors [32,63]. Stakeholders’ (e.g., consumers’) skepticism toward an organization’s CSR involvement largely targets its CSR motives [64]. In particular, they tend to doubt “why” organizations engage in CSR [65]. Current research on the dimensions of CSR attributions is largely drawn from the marketing and business literature [58,63,66,67]. For example, consumers’ perceptions of companies’ CSR initiatives were categorized into egoistic-driven (i.e., exploiting the cause rather than helping it), strategic-driven (i.e., attaining business goals while benefiting the cause), values-driven (i.e., benevolence-motivated giving), and stakeholder-driven (i.e., supporting a social cause solely due to pressure from stakeholders) motives [68,69]. Vlachos et al. [70] redefined CSR motives into two categories: CSR-induced (1) intrinsic/other-serving and (2) extrinsic/self-serving motives. Intrinsic/other-serving motives, corresponding to value- and stakeholder-driven attributions, represent organizations’ genuine intent to meet certain social needs. Conversely, extrinsic motives capture egoistic- and strategic-driven attributions, causing stakeholders to interpret organizations’ engagement with CSR as window-dressing or self-serving intentions [26]. In the present study, we focus on employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving CSR motives.

2.3. Linking Informativeness and Factual Message Tone to Employee-Perceived Intrinsic Motives for CSR

Based on previous and persuasive studies, Kim and Rim [71] suggested that when stakeholders cope with corporate CSR messages that lack credibility, their existing persuasion knowledge is activated and results in an increased level of skepticism toward the specific messages that they receive. In alignment with this argument, scholars [39,49,50,51,72] argued that skepticism can be attenuated by effective CSR communication, in particular, by informative communication substantiated with messages on an organization’s CSR achievements and outcomes, motives and intentions, CSR beneficiaries’ information, and the evidence of third-party endorsement. It is pivotal to consistently share up-to-date CSR information with stakeholders, as informativeness can minimize skepticism and enhance stakeholders’ perception of a company’s intrinsic or other-serving CSR motives [39]. Likewise, as indicated by the theory of information economics [71]), stakeholders become less skeptical when they can verify a company’s CSR messages with proven facts. Communicating in a factual tone is, thus, fundamental to stakeholders’ perceived trust in CSR messages and significantly affects their evaluation of CSR motives as intrinsic or altruistic [49]. Based on data collected in a cross-sectional online survey (n = 927), Kim and Rim [71] yielded empirical evidence that was indicative of a significant relationship between CSR messages with substantial information delivered in a factual tone and consumers’ reduced skepticism toward altruism in their selected brands’ corporate CSR motives. Applying the above reviewed lines of research to employees as internal stakeholders of their organizations, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

Informativeness (H1a) and a factual tone (H1b) in CSR communication are positively related to employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives for their organizations’ CSR activities.

2.4. Employee Organizational Identification

Based on social identity theory (SIT) [73,74], employees have an innate need to satisfy their self-identities and self-images by aligning themselves with a social group (e.g., an organization). Identifying themselves as members of a socially responsible organization appears to be a desirable attribution for employees, reinforcing their self-identities [40]. CSR activities thus serve as a salient method for employees to derive meaning and pride from their organizations’ socially responsible behaviors [75]. Recent studies [41,76,77,78] revealed that employees exhibited stronger organizational identification when their employers were involved in socially responsible undertakings. An extension of the concept of organizational identification (OI) as “the perception of oneness with or belongingness to an organization” (p. 104, [79]), employee organizational identification describes the extent to which employees define themselves through their organizations and derive value from that self-definition [73].

2.5. Connecting CSR Motives to Organizational Identification

Previous studies [33,77,78] have shown that employees display stronger OI when their organizations are involved in CSR activities. The association between CSR perceptions and organizational identification is rooted in social identity theory [24]. The extent to which individuals identify with organizations is contingent upon whether identifying with such organizations promotes their self-esteem or self-concept [80,81]. Individuals are more inclined to identify with a group or social entity that demonstrates socially desirable values and is deemed by others to be responsible; this is because psychologically associating oneself with such socially attractive groups enhances an individual’s self-concept and self-worth in return [40]. CSR motives (intrinsic vs. extrinsic) can thus signal the social desirability of the organizations’ actions. In particular, organizations engaged in genuine, socially responsible initiatives conducted with the goal of fulfilling one’s obligation to society (i.e., intrinsic motives) tend to be perceived as attractive, distinctive, and respected. Employees are naturally inclined to feel connected and identify with these desirable organizational attributes because those attributes reflect their self-worth and align with their needs for self-enhancement [41,42]. Therefore, when an organization’s motives for its CSR activities are attributed primarily to serving the greater good (i.e., intrinsic motives) by its employees, a stronger level of employee organizational identification is likely to occur. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

Employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives of their organizations’ CSR activities are positively associated with employee organizational identification.

2.6. Corporate Reputation

As the most significant intangible asset in management (p. 12, [82]), corporate reputation represents the stakeholders’ collective perceptions of how an organization has satisfied their expectations [83]. As reputation reveals “the degree to which stakeholders perceive a company as good or bad” (p. 185, [84]), numerous studies [85,86,87,88,89] have investigated the impact of CSR on corporate reputation. CSR programs are indicative of an organization’s commitment to engaging in activities aiming to advance environmental and social goals beyond their financial and legal obligations to stakeholders [90,91,92], 2022. Stakeholders’ assessments of CSR thus constitute an essential reference point for gauging corporate reputation [93]. Existing studies [94,95,96] have generally converged on a directly as well as indirectly positive relationship between CSR and corporate reputation. For example, Berber et al. [91] found a significant direct positive relationship between CSR perceptions and corporate reputation. Yadav et al.’s [97] study suggested a positive relationship between CSR and corporate reputation that was mediated by employee trust. Bianchi et al. [98] discovered a similar indirect effect of perceived CSR on company reputation through customer loyalty.

The perceptions of corporate reputation are shaped through organizations’ interactions with various stakeholders, particularly with those employees identified as a major force in shaping corporate reputation [49]. Echoing this sentiment, this study seeks to explore the impact of employees’ CSR perceptions (i.e., perceived CSR motives) on internal corporate reputation, defined as employees’ overall evaluation of their employers according to Men and Stacks [99]. When employees evaluate corporate reputation favorably, they tend to be more committed to their organizations’ mission, values, beliefs, and objectives [100,101]. Moreover, internal reputation is positively associated with external reputation since stakeholders trust employees’ judgment regarding their own organizations [102,103]. Employees’ reputation evaluations are more credible than those from external sources.

Widely adopted and consistently validated dimensions of corporate reputation are derived from the RepTrak system [104]. This RepTrak system, identified by Fombrun et al. [105], includes six key dimensions of corporate reputation: (1) emotional appeal, (2) vision and leadership, (3) workplace environment, (4) products and services, (5) social and environmental responsibility, and (6) financial performance. Emotional appeal refers to the emotional attachment arising from stakeholders’ experiences with a company and their comprehensive understanding of the company that follows. Vision and leadership indicate that excellent and visionary leaders of a company largely determine its competitive position in the industry and make stakeholders its strong endorsers. The workplace environment has much to do with the way a company treats its employees. Products and services reflect stakeholders’ evaluations of whether a company offers its customers high-quality, valuable products and services. As relational assets, social and environmental responsibility activities help a company to display its corporate citizenship behavior and generates various forms of corporate support in communities at all levels. Lastly, financial performance is indicative of whether a company is solid and sound in the market [105].

2.7. Associating Organizational Identification with Corporate Reputation

Organizational identification has been considered a significant driver of group members’ attitudes and behaviors (Chen et al., 2023 [41]; Freire et al., 2022 [75]). Corporate reputation is a socio-cognitive construct that is influenced by knowledge, impressions, experience, and beliefs about the organization [103]. Several scholars [106,107] in brand management have long argued for the positive association between consumer identification with a brand and brand equity (i.e., the business value derived from consumer perceptions of how reputable a brand is). Desirable associations with brands’ central characteristics and values contribute to customers’ positive evaluations of brand reputation. When organizational identification is strong, employees tend to respond positively to the needs of their organizations and display favorable attitudes toward their employers [108]. In particular, stakeholders rely on an organization’s core values and beliefs as the basis of their perceptions about corporate reputation [51]. Stakeholders’ perceptions of an alignment between their self-concept and the core, distinctive attributes of their organizations’ identity are, thus, likely to yield a positive evaluation of their employers’ reputation [109]. In the context of this study, CSR communication provides an opportunity for organizations to make their fundamental values and beliefs salient to their stakeholders (e.g., their employees). Through such a value assessment, when stakeholders recognize a congruence between their personal identity and organizational identity, individuals possess a sense of pride for their organization that represents their values and beliefs. As a result, such alignment evokes positive evaluations about their organizations (e.g., reputation) [110]. Based on the above reasoning, we thus propose the following hypothesis:

H3:

Employee organizational identification is positively related to corporate reputation.

2.8. Perceived Intrinsic CSR Motives and Employee Organizational Identification as Mediators

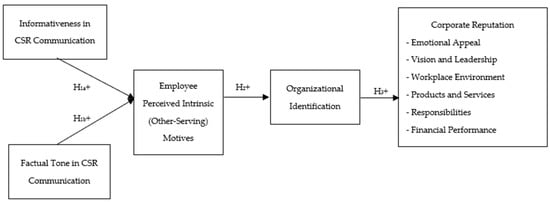

Although many studies [49,86,87,89,91] in the fields of business and marketing have confirmed the positive relationship between CSR and corporate reputation, little of the research has explored the effects of CSR communication on corporate reputation [47]. This study thus attempts to address this gap by probing the links between specific dimensions (i.e., message informativeness and message tone) of CSR communication and corporate reputation in the context of employee stakeholders. Informed by social identity theory, individuals classify themselves as members of a social group to satisfy their self-identities and self-worth [79]. Employees thereby build their self-identify from their perceptions of organizational characteristics (e.g., CSR) and translate them into attitudes and behavior [73]. Therefore, this study focuses on the mediating role of organizational identity in linking CSR communication to organizational outcomes, such as corporate reputation. The positive impact of CSR on corporate reputation underscores the pivotal role of CSR communication in fostering employees’ awareness and understanding of organizations’ CSR involvements [1,96]. CSR is inherently value-driven as organizations strive to be socially responsible by creating the benefits of sustainability for various stakeholders (e.g., environment, community, society, employees, etc.). Individuals have an innate tendency to look for the attributions of activities [111]; employees, therefore, seek cues, such as motives for CSR, to form perceptions about their employers’ CSR undertakings. Altruistic or other-serving CSR motives make organizations appear more socially attractive to their stakeholders (e.g., employees, customers, etc.). Consequently, such favorable perceptions of CSR motives provide a strong incentive for stakeholders to identify more closely with the organizations involved in these CSR efforts because associating oneself with a socially responsible group improves individuals’ self-esteem and self-worth [40]. Such organizational identification satisfies stakeholders’ primary self-definitional and emotional needs [112]. Naturally, employees’ strong psychological attachment to organizations (i.e., organizational identification) drives them to perceive organizations’ overall ability and performance as positive. Such favorable assessments form the essential components of corporate reputation. CSR motives and employee organizational identification thus function as mediators between CSR communication and corporate reputation. In this vein, we propose our final set of hypotheses about the indirect effects seen in our proposed model (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The conceptual model (H4a-b and H5a-c refer to the indirect effects in the model).

H4:

Employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives mediate the relationship between informativeness (H4a) and employee organizational identification, as well as that between factual tone (H4b) and identification.

H5a:

Employee organizational identification mediates the relationship between employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives and corporate reputation.

H5b&c:

Employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives and employee organizational identification mediate the relationship between informativeness (H5b) and corporate reputation, as well as that between factual tone (H5c) and corporate reputation.

3. Method

3.1. Procedures for Data Collection

To test the proposed hypotheses in the present study, we conducted a Qualtrics survey using Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) between 23 March and 27 March 2018. MTurk helps researchers to collect high-quality data [113,114]. Participants recruited via MTurk are demographically diverse; the program provides participants with moderate compensation rates that do not compromise the quality of collected data; and MTurk data are as reliable as those obtained through traditional survey methods (p. 3, [115]). We only recruited full-time employees who lived in the US at the time of data collection and reported to have ever participated in their employers’ CSR activities. Our Qualtrics survey accomplished a total of 955 responses. Among them, 811 responses (84.9%) were complete and thus usable. Each participant who completed all survey questions was compensated with USD 1.00.

3.2. Sample Characteristics

As shown in Table 1, our sample consisted of 46.4% males (n = 376) and 53.5% females (n = 434). The mean age of the 811 participants was 38 (SD = 10.41). As for race and ethnicity, 78.9% of the participants (n = 640) self-identified as white or non-Hispanic, with 4.1% of them (n = 33) self-identified as Hispanic American, 8.1% (n = 66) as African American, 0.5% (n = 4) as Native American, 6.3% (n = 51) as Asian American/Pacific Islander, 1.5% (n = 12) as multicultural, and 0.6% (n = 5) as other. In terms of organizational size, 27.5% of the participants (n = 223) worked for organizations with fewer than 250 employees, 24.9% (n = 202) with between 250 and 1000, 15.3% (n = 124) with between 1001 and 5000, 10.0% (n = 81) with between 5001 and 10,000, 6.3% (n = 51) with between 10,001 and 50,000, 8.1% (n = 66) with between 50,001 and 100,000, and 7.9% (n = 64) with more than 100,000 employees. The average number of employees that participants directly supervised was 27 (SD = 357.63). In addition, the participants had worked an average of 7.30 (SD = 6.02) years for their employers at the time of data collection. Our sample consisted of 293 (36.1%) non-management, 236 (29.1%) lower-level management, 255 (31.4%) middle-level management, and 27 (3.3%) top management employees. In terms of the participants’ highest level of education, the three largest groups included (1) 455 bachelor’s degrees (56.1%), (2) 157 master’s (19.4%), and (3) 141 high-school graduates (17.4%). Finally, the four top annual salary ranges that participants reported were USD 50,000–59,999 (n = 139, 17.1%), USD 40,000–49,999 (n = 123, 15.2%), USD 30,000–39,999 (n = 122, 15.0%), and USD 60,000-69,999 (n = 99, 12.2%).

Table 1.

Participant profile for the study (n = 811).

3.3. Independent and Dependent Measures

All survey items in the present study used a seven-point Likert-type scale (e.g., 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”). To measure participants’ perceptions of informativeness (α = 0.92) and a factual tone (α = 0.77) in their organizations’ CSR communication with stakeholders, we used 10 items that Kim [47] and Kim and Ferguson [35] proposed. Four items that have been used extensively in the prior literature [70,116] were adopted to measure employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives for CSR (α = 0.91). We adapted six items from the study by Barge and Schlueter [117] to measure participants’ identification with their employers (α = 0.96). Lastly, 20 items from the Harris–Fombrun reputation quotient [118] was adopted to measure participants’ perceptions of their employers’ corporate reputation (α = 0.97), with three items for emotional appeal (α = 0.94), three items for vision and leadership (α = 0.88), three items for workplace environment (α = 0.89), four items for products and services (α = 0.90), three items for social and environmental responsibilities (α = 0.85), and four items for financial performance (α = 0.87).

3.4. Data Analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses with the Mplus 7.4 program [119] was conducted to test the proposed hypotheses. To determine the data-model fit for both the measurement (CFA) and the structural (SEM) models, we used the criteria that Hu and Bentler [120] (1999) proposed—the comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.96 and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.10 or the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06 and SRMR ≤ 0.10).

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Data Analysis

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

We used the following breakdown of scale points to report the values of all measured variables—“low (1.00–2.50);” “moderately low (2.51–3.99);” “neutral (4);” “moderately high (4.01–5.49);” and “high (5.50–7.00).” Participants perceived the levels of informativeness (M = 5.03, SD = 1.22) and a factual tone (M = 4.74, SD = 1.11) in their employers’ CSR communication to be moderately high. Additionally, participants reported a moderately high level of employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives for CSR (M = 5.25, SD = 1.23). Participants also moderately highly identified with their organizations (M = 5.00, SD = 1.43). Finally, their reported levels of corporate reputation (M = 5.32, SD = 1.13) were moderately high as well (Memotional appeal = 5.32, SD = 1.42; Mvision and leadership = 5.21, SD = 1.38; Mworkplace environment= 5.31, SD = 1.34; Mproducts and services = 5.46, SD = 1.18; Mresponsibilities = 5.41, SD = 1.21; Mfinancial performance = 5.20, SD = 1.19). Correlations between the variables in the structural model ranged from 0.46 to 0.81 (p < 0.01) (see Table 2). In addition to the descriptive statistics, we also conducted robustness tests. Collinearity diagnostics uncovered no multicollinearity issue between the exogenous variables in the proposed model. The collinearity tolerance values for informativeness in CSR communication and a factual tone in CSR communication are 0.792 and 0.792, with employee-perceived intrinsic motives for CSR as the endogenous factor in the model. The VIF values are less than 2.50, with 1.263 for both informativeness and a factual tone in CSR communication. As for another robustness check, we tested the results for managerial employees and non-managerial employees and found no significant differences.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics (alpha, mean, standard deviation, and correlations) (n = 811).

4.1.2. Tests on Control Variables

A series of preliminary, hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted to identify the variables to be controlled in our SEM analysis. The results of the analyses revealed age to be a significant predictor for a perceived factual tone in CSR communication (βage = 0.15, t = 3.72, p < 0.001) and the level of management position for organizational identification (βlevel of position = −0.09, t = −3.40, p = 0.001). Based on the results of the preliminary tests and the relevant prior literature, we controlled for age and level of management position in SEM analysis. Both turned out to be significant: βage->factual tone in CSRcomm = 0.14, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: 0.08 to 0.19); βlevel of management position->organizational identification = −0.10, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: −0.15 to 0.05).

4.2. Measurement Model/CFA Analysis Results

Please see Table 3 for all the measurement items, along with the standardized factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVEs), and composite reliability (CR) values. Our CFA model achieved a good data-model fit: χ2 = 2169.44, df = 693, n = 811, χ2/df = 3.13, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.05 [90% CI = 0.049-.054], CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95.

Table 3.

Results of the Measurement Model, AVE & CR (n = 811).

4.3. Findings of Hypothesis Testing

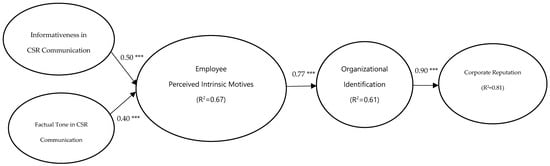

Our hypothesized structural model also accomplished a good fit with the collected data: χ2 = 2456.35, df = 776, n = 811, χ2/df = 3.17, SRMR = 0.07, RMSEA = 0.05 [90% CI = 0.049−0.054], CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94. All proposed hypotheses were supported (see Figure 2). The results of hypothesis testing are presented in Table 4.

Figure 2.

The final structural model, with standardized path coefficients. χ2 = 2456.35, df = 776, n = 810, χ2/df = 3.17, SRMR = 0.07, RMSEA = 0.05 [90% CI = 0.049−0.054], CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94. *** p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Results of Hypothesis Testing.

4.3.1. H1a to H3 (Direct Effects)

When employees perceived their employers’ CSR communication with stakeholders to be highly informative and factual in tone, they were more likely to believe that the motives of their organizations’ CSR activities were intrinsic or other-serving [βinformativeness ->intrinsic or other-serving motives = 0.50, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: 0.39 to 0.60), H1a was supported; βfactual tone ->intrinsic or other-serving motives = 0.40, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: 0.30 to 0.51), H1b was supported]. When they perceived intrinsic or other-serving CSR motives, they tended to highly identify with their employing organizations [βintrinsic or other-serving motives->organizational identification = 0.77, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: 0.72 to 0.82), H2 was supported]. When employees highly identified with their employers, they tended to think of their organizations’ reputation positively [βorganizational identification->corporate reputation = 0.90, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: 0.87 to 0.92), H3 was supported].

4.3.2. H4a to H5c (Indirect Effects)

Results of the mediation tests with a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure (N = 5000 samples) found employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives for CSR to be a significant mediator for the relationship between informativeness and organizational identification [βinformativeness->intrinsic or other-service motives->organizational identification = 0.38, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: 0.30 to 0.47)] and that between factual tone and organizational identification [βfactual tone->intrinsic or other-service motives->organizational identification = 0.38, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: 0.30 to 0.47)]. Thus, H4a and H4b were supported. Moreover, both employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives for CSR and organizational identification significantly mediated the relationships among informativeness, factual tone, and corporate reputation [βintrinsic or other-service motives->organizational identification->corporate reputation = 0.70, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: 0.64 to 0.75); βinformativeness->intrinsic or other-service motives->organizational identification->corporate reputation = 0.35, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: 0.27 to 0.42); βfactual tone->intrinsic or other-service motives->organizational identification->corporate reputation = 0.28, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001 (BC 95% CI: 0.21 to 0.36)]. H5a, H5b, and H5c were supported as well.

5. Discussion

Given the soaring expectations from stakeholders and the impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational reputation and performance, organizations’ CSR undertakings have become obligatory [1]. Stakeholder evaluations of organizations’ CSR programs rely on their CSR awareness and interpretations, which makes CSR communication imperative for shaping stakeholder CSR perceptions and optimizing CSR’s organizational outcomes [17,23,62,121]. As a critical stakeholder group, employees possess significant power to influence organizations’ CSR agenda and outcomes [21,30,44,122]. Especially, Berniak-Woźny et al. [2] reported that there is still a lack of research focusing on the employees’ perspectives of CSR. Understanding the psychological mechanism of employees’ CSR appraisals is, hence, paramount to organizations’ effective CSR management. This study examined the impact of CSR communication on employee CSR-induced perceptions, such as CSR motives, organizational identification, and corporate reputation, thus linking the micro-impact of CSR initiatives on internal stakeholders to macro-organizational outcomes, such as reputation assessment.

First, this study fills in the current void regarding effective CSR communication [32,49,60]. The findings of this study yield empirical support regarding the validity and utility of the key dimensions of informativeness and tone in CSR communication, as proposed by Kim and Ferguson [35,123]. In particular, this study confirms existent studies about the significant role that CSR communication content (i.e., informativeness) and tone (i.e., a factual message tone) play in evoking positive employee perceptions (i.e., perceived CSR motives and OI) and, ultimately, reputation assessment. For example, Schmeltz [72] supported the effectiveness of integrating the Triple Fit model (i.e., aligning the values of consumers, company, and CSR) in strategic CSR communication to foster consumers’ positive CSR perceptions, which echoed the efficacy of the CSR communication dimension of the CSR fit examined in this study. Similarly, Lee and Cho [61] found that CSR-fit-focused CSR communication led to a higher level of public-serving motives (i.e., intrinsic CSR motive) than low CSR-fit-oriented communication. Kang and Atkinson [51] found that objective (e.g., fact-based data, outcome-focused data) messages effectively fostered public-serving CSR motives and a favorable corporate reputation among consumers. Lim and Jiang [62]’s study revealed that engaging in genuine communication about CSR motives, a clear association between CSR initiatives and organizational identity, and consistent communication about CSR activities and promises significantly contributed to favorable relational outcomes among stakeholders.

It is evident that this study yields empirical support for the validity and utility of the key dimensions regarding informativeness and tone in CSR communication, as examined in previous CSR communication research [51,61,62]. The four key dimensions in message content—CSR commitment (e.g., the number and value of donations), CSR impact (e.g., the specific social impact of their CSR endeavors), CSR motives (e.g., other-/public-serving or self-serving), and CSR fit (e.g., the congruence between an organization’s business and its CSR initiatives)—can serve as a concrete yardstick to gauge when, how, and why CSR message content can promote favorable employee perceptions. Adopting a factual instead of a self-praising tone induces a positive CSR motive attribution among employees. Noticeably, message content has a stronger influence on employee CSR attributions than message tone. Examining the two key dimensions (i.e., message content and tone) in the process of CSR communication illustrates that a crucial impact of effective CSR communication lies in minimizing stakeholder skepticism or doubt about organizations’ motives for engaging in CSR activities.

Second, this study responds to the urgent call of investigating how employees respond to and assess CSR [2,17,30,44,124]. The area of study probing the micro-level effects of CSR (e.g., employee CSR perceptions and behaviors) remains in the nascent stage [9,24,29,37,41,100]. This study fills this void by elucidating the psychological mechanisms underlying employees’ CSR-driven reactions. As indicated by the findings of this study, organizations’ CSR behaviors significantly affected employees via organizational identification. We contribute to the growing body of stakeholder-centric CSR literature [75,125,126,127] by presenting an identity-based mechanism to explain the extent and degree of employee identification with socially responsible organizations.

Importantly, as is distinct from many existing studies [24,30,69] and treating CSR attributions or motives as an antecedent, this study particularly examined the dimensions of CSR communication as antecedent to influencing employees’ perceptions of CSR motives. This enriches the existing understanding, from a communication approach, of how to mitigate resistance against an organization’s CSR messages and cultivate positive inferences regarding CSR motives among stakeholders. The results of this study have identified CSR-induced motive attribution as a salient psychological condition under which CSR can stimulate positive employee attitudes. When an organization engages in altruistic, other-serving behaviors to fulfill its social obligations for the greater good, the organization appears more socially attractive and desirable. This increased attractiveness reinforces employees’ identification with their organizations, which echoed the existing literature on the relationship between organizational attractiveness and employee identification [40,42,78,80]. Internally, employees improve their self-concept by feeling proud that their organizations have contributed to the well-being of society, resulting in stronger organizational identification. By illuminating this cognitive pathway via the influence of CSR on employee identification, this study examines the nature of the relationship between CSR and employee perceptions, which also sheds light on how CSR programs can be effectively planned and executed.

Lastly, this study contributed to our understanding of how the cognitive evaluation of CSR motives among employees can affect the overall macro-level assessment of corporate reputation through organizational identification. Viewed as one of the most valuable intangible assets [49,82,94,128], reputation has a vital influence on stakeholder behavior, such as product purchase [129,130], supportive word of mouth (WOM) [60,131], or employment choice [49,132]. This study presents a clear link between two CSR communication factors (i.e., message content and tone) and corporate reputation, through the influence of two mediators: employee-perceived CSR intrinsic motives and organizational identification. A favorable corporate reputation can be cultivated among employees by imparting informative CSR communication with a factual tone. This link emphasizes that the impact of CSR communication on corporate reputation is a non-linear process mediated by perceptions of organizations’ true motives and employee organizational identification.

In conclusion, data collected from an online Qualtrics survey (n = 811) supported all the proposed hypotheses in the present study. Specifically, informativeness and a factual tone in CSR communication were positively related to employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives of their organizations’ CSR activities. Employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives of their organizations’ CSR activities were positively associated with employee organizational identification. Employee organizational identification was positively related to corporate reputation. In addition, employee-perceived intrinsic/other-serving motives of their organizations’ CSR activities and employee organizational identification acted as two significant mediators in the proposed model.

6. Practical Implications

This study generates significant implications for CSR communication within organizations to both communication practitioners and management. First, understanding the factors determining the effectiveness of CSR communication can guide communication practitioners to design what message content and what message tone should be communicated in order to manage the stakeholders’ awareness of an organization’s CSR initiatives and overcome their skepticism of an organization’s CSR communication and its intention when supporting a social cause. Second, knowing how employees cognitively evaluate and respond to CSR communication enables communication professionals and management to maximize the positive impact of CSR activities by using communication to target employees’ CSR-induced motive interpretation and organizational identification. Third, communication practitioners can employ the two fundamental CSR communication factors (i.e., message content and tone) to evaluate the effectiveness of CSR communication programs and, hence, develop appropriate interventions to optimize the effectiveness of CSR communication. This evaluation can demonstrate how CSR communication can create a competitive advantage by creating a loyal workforce and ultimately affecting external reputation. Fourth, understanding how employees respond to CSR initiatives empowers organizations to better serve employees’ needs while fostering positive social change.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations of this study are worth noting. First, we believe that self-reporting is most appropriate for our study because several key constructs—perceived CSR intrinsic motives and organizational identification—are perceptual constructs. However, a self-report survey method may result in social desirability bias [133]. In addition, all the measures in our questionnaire were based on the perceptions of the survey participants. It is hard to build causal relationships among the variables. That said, we proposed only significant positive associations among the variables (see our hypotheses). Second, CSR focuses on stakeholders’ expectations regarding organizations’ social obligations. Culture may create a variance in terms of what is deemed to be socially responsible for organizations. To achieve broader generalizability, future research should examine how employees in different cultural groups perceive CSR motives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and H.J.; Methodology, Y.L. and H.J.; Software, H.J.; Formal analysis, H.J.; Data curation, H.J.; Writing—original draft, Y.L., H.J. and L.Z.; Writing—review & editing, Y.L., H.J. and L.Z.; Supervision, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Syracuse University (Jiang-18-106). Prior to participating in the study, all participants gave their informed consent.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ajayi, O.A.; Mmutle, T. Corporate reputation through strategic communication of corporate social responsibility. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2021, 26, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berniak-Woźny, J.; Kwasek, A.; Gąsiński, H.; Maciaszczyk, M.; Kocot, M. Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility in Small and Medium Enterprises—Employees’ Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 15, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.; Choi, C.-W.; Overton, H.; Kim, J.K.; Zhang, N. Feeling Connected to the Cause: The Role of Perceived Social Distance on Cause Involvement and Consumer Response to CSR Communication. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2022, 99, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.; Moon, T.; Kim, H. When and how does customer engagement in CSR initiatives lead to greater CSR participation? The role of CSR credibility and customer–company identification. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1878–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peasley, M.C.; Woodroof, P.J.; Coleman, J.T. Processing contradictory CSR information: The influence of primary and recency effects on the consumer-firm relationship. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 172, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahat, M.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Ramayah, T. Analysing the importance of international knowledge, orientation, networking and commitment as entrepreneurial culture and market orientation in gaining competitive advantage and international performance. Int. Mark. Rev. 2021, 39, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Sung, Y. Shaping Corporate Character Through Symmetrical Communication: The Effects on Employee-Organization Relationships. J. Bus. Commun. 2022, 59, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelson, A.C.; Hesse, C. Conceptualizing and Validating Organizational Communication Patterns and Their Associations with Employee Outcomes. J. Bus. Commun. 2023, 60, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, B.; Ong, T.S.; Meero, A.; Rahman, A.A.A.; Ali, M. Employee-perceived corporate responsibility (CSR) and employee pro-environemntal behavior (PEB): The moderating role of CSR skepticism and CSR authenticity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, S.; Hull, C.E.; Tang, Z. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Corporate Social Performance Strengths and Concerns. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 391–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Hull, C.E.; Rothenberg, S. How Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement Strategy Moderates the CSR-Financial Performance Relationship. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1274–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, L.T. Impact of internal CSR perception on affective organizational commitment among bank employees. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 25, 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Loor-Zambrano, H.Y.; Santos-Roldán, L.; Palacios-Florencio, B. Relationship CSR and employee commitment: Mediating effects of internal motivation and trust. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.H.; Iqbal, K.; Santoro, G.; Rizzato, F. The impact of corporate social responsibility directed toward employees on contextual performance in the banking sector: A serial model of perceived organizational support and affective organizational commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1980–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.-W.; Choi, W.-H. The Role of Job Crafting and Perceived Organizational Support in the Link between Employees’ CSR Perceptions and Job Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3151–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulou, E.-C.; Manolopoulos, D.; Agapitou, V. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Outcomes: Interrelations of External and Internal Orientations with Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 179, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S.D.; Terlutter, R.; Diehl, S. Talking about CSR matters: Employees’ perception of and reaction to their company’s CSR communication in four different CSR domains. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, J.S.P.; Castanheira, F. Corporate social responsibility and employee performance: Mediation role of job satisfaction and affective commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lho, L.H.; Han, H. Corporate social responsibility (environment, product, diversity, employee, and community) and the hotel employees’ job performance: Exploring the role of the employment types. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1825–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On Corporate Social Responsibility, Sensemaking, and the Search for Meaningfulness Through Work. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-T.; Liu, N.-C.; Lin, J.-W. Firms’ adoption of CSR initiatives and employees’ organizational commitment: Organizational CSR climate and employees’ CSR-induced attributions as mediators. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Lee, S.Y. Cognitive processing of corporate social responsibility campaign messages: The effects of emotional visuals on memory. Media Psychol. 2020, 23, 244–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, E.; Sekhon, T.; Salinas, T.C. Do well, do good, and know your audience: The double-edged sword of values-based CSR communication. J. Brand Manag. 2022, 29, 598–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Rehman, Z.U.; Umrani, W.A. Retracted: The moderating effects of employee corporate social responsibility motive attributions (substantive and symbolic) between corporate social responsibility perceptions and voluntary pro-environmental behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boğan, E.; Sarıışık, M. Organization-related determinants of employees’ CSR motive attributions and affective commitment in hospitality companies. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donia, M.B.L.; Sirsly, C.T.; Ronen, S. Employee attributions of corporate social responsibility as substantive or symbolic. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 24, 232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach, D.G.; Vlachos, P.A.; Irwin, K.; Morgeson, F.P. Does “how” firms invest in corporate social responsibility matter? An attributional model of job seekers’ reactions to configurational variation in corporate social responsibility. Hum. Relat. 2022, 75, 532–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waples, C.J.; Brachle, B.J. Recruiting millennials: Exploring the impact of CSR involvement and pay signaling on organizational attractiveness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, E.L. Linking perceived corporate social responsibility and employee well-being—A Eudaimonia perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.A.; Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Khan, W.; Rehman, Z.U.; Khan, M.A.S. Impact of corporate social responsibility attributions on employee's extra-role behaviors: Moderating role of ethical corporate identity and interpersonal trust. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H. Attribution theory in social psychology. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Levine, D., Ed.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Schade, J.; Wang, Y.; van Pooijen, A.-M. Consumer skepticism towards corporate-NGO partnership: The impact of CSR motives, message frame and fit. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2022, 27, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Overton, H.; Bhalla, N.; Li, J.Y. Nike, Colin Kaepernick, and the pollicization of sports: Examining perceived organizational motives and public responses. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Kim, S. Dimensions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) skepticism and their impacts on public evaluations toward CSR. J. Public Relat. Res. 2016, 28, 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ferguson, M.A.T. Dimensions of effective CSR communication based on public expectations. J. Mark. Commun. 2018, 24, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Tao, W. Unpack the relational and behavioral outcomes of internal CSR: Highlighting dialogic communication and managerial facilitation. Public Relat. Rev. 2022, 48, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Tao, W. Employees as information influencers of organization’s CSR practices: The impacts of employee words on public perceptions of CSR. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F.; Kang, J. How to alleviate consumer skepticism concerning corporate responsibility: The role of content and delivery in CSR communications. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2477–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Kochigina, A. Engaging through stories: Effects of narratives on individuals’ skepticism toward corporate social responsibility efforts. Public Relat. Rev. 2021, 47, 102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.; Afsar, B.; Javed, F. Employees’ corporate social responsibility perceptions and organizational citizenship behaviors for the environment: The mediating roles of organizational identification and environmental orientation fit. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Gonçalves, J.; Carvalho, M.R. Corporate Social Responsibility: The Impact of Employees’ Perceptions on Organizational Citizenship Behavior through Organizational Identification. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.A.; Cheema, S.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Ali, M.; Rafiq, N. Perceived corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behaviors: The role of organizational identification and coworker pro-environmental advocacy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Ruso, M.; Aibar-Guzmán, B. The moderating effect of contextual factors and employees’ demographic features on the relationship between CSR and work-related attitudes: A meta-analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1839–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garel, A.; Petit-Romec, A. Engaging Employees for the Long Run: Long-Term Investors and Employee-Related CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 174, 35–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Donia, M.B.; Shahzad, K. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Attributions on Employees’ Creative Performance: The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety. Ethic-Behav. 2019, 29, 490–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, A.; Morsing, M.; Moon, J. Corporate Social Responsibility: Strategy, Communication, Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. The process model of corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication: CSR communication and its reslationship with consumers’ CSR knowledge, trust, and corporate reputation perception. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 1143–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, B.A.; Jan, A.N.; Subramani, A.K. Building corporate reputation through corporate social responsibility: The mediation role of employer branding. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2022, 49, 1770–1786. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. The process of CSR communication—Cultural-specific or universal? Focusing on Mainland China and HongKong consumers. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2022, 59, 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, T. Transmedia storytelling: A potentially vital resource for CSR communication. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2019, 24, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.Y.; Atkinson, L. Effects of message objectivity and focus on green CSR communication: The strategy development for a hotel’s green CSR message. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 27, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, C.-D.; Kim, J. The effects of CSR communication in corporate crises: Examining the role of dispositional and situational CSR skepticism in context. Public Relat. Rev. 2020, 46, 101792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R. When Consumers Are Skeptical of a Company “Doing Good:” Examining How Company-Cause Fit and Message Specificness Interplay on Consumer Responses toward Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas in Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanesh, G.S.; Nekmat, E. Facts Over Stories for Involved Publics: Framing Effects in CSR Messaging and the Roles of Issue Involvement, Message Elaboration, Affect, and Skepticism. Manag. Commun. Q. 2019, 33, 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A. Building a theoretical framework of message authenticity in CSR communication. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2019, 24, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Maximizing Business Returns to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of CSR Communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, S.; Grappi, S.; Bagozzi, R.P. Corporate Socially Responsible Initiatives and Their Effects on Consumption of Green Products. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Prooijen, A.; Bartels, J.; Meester, T. Communicated and attributed motives for sustainability initiatives in the energy industry: The role of regulatory compliance. J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 20, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.E.; Lee, W. Communicating corporate social responsibility: How fit, specificity, and cognitive fluency drive consumer skepticism and response. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla-Pria, L.; Rodríguez-De-Dios, I. CSR communication on social media: The impact of source and framing on message credibility, corporate reputation and WOM. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2022, 27, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Cho, M. Socially stigmatized company’s CSR efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effects of CSR fit and perceived motives. Public Relat. Rev. 2022, 48, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.S.; Jiang, H. Linking Authenticity in CSR Communication to Organization-Public Relationship Outcomes: Integrating Theories of Impression Management and Relationship Management. J. Public Relat. Res. 2021, 33, 464–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teah, K.; Sung, B.; Phau, I. CSR Motives on situation skepticism towards luxury brands. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2022, 40, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabashkina, L.; Tarabashkina, O.; Quester, P. Using numbers in CSR communication and their effects on motive attributions. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasuwa, G. Do consumers really care about organizational motives behind CSR? The moderating role of trust in the company. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Chang, Y.K.; Li, Y.J.; Jang, M.G. Doing Good in Another Neighborhood: Attributions of CSR Motives Depend on Corporate Nationality and Cultural Orientation. J. Int. Mark. 2016, 24, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunfowora, B.; Stackhouse, M.; Oh, W.-Y. Media Depictions of CEO Ethics and Stakeholder Support of CSR Initiatives: The Mediating Roles of CSR Motive Attributions and Cynicism. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnakaran, S.T.; Edward, M. Evaluating cause-marketing campaigns in the Indian corporate landscape: The role of consumer skepticism and consumer attributions of firm's motive. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2019, 24, e1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, A.; Miletić, L.; Čurčić, R.; Ničić, M. Consumers’ perception of CSR motives in a post-socialist society: The case of Serbia. Bus. Ethic—A Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A. Feeling Good by Doing Good: Employee CSR-Induced Attributions, Job Satisfaction, and the Role of Charismatic Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Rim, H. The Role of Public Skepticism and Distrust in the Process of CSR Communication. J. Bus. Commun. 2019, 2329488419866888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeltz, L. Getting CSR communication fit: A study of strategically fitting cause, consumers and company in corporate CSR communication. Public Relat. Inq. 2017, 6, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in Organizations: An Examination of Four Fundamental Questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social identity and intergroup behavior. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-K.; Tang, A.D.; Tuan, L.T. The mediating role of organizational identification between corporate social responsibility dimensions and employee opportunistic behavior: Evidence from symmetric and asymmetric approach triangulation. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 32, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudencio, P.; Coelho, A.; Ribeiro, N. The impact of CSR perceptions on workers’ turnover intentions. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 17, 543–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, H.; Morrison, A.M. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, K.; Lv, M.; Zheng, H. Corporate Social Responsibility and Cheating Behavior: The Mediating Effects of Organizational Identification and Perceived Supervisor Moral Decoupling. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassar, A.-N.; Yunis, M.; Alsagheer, A.; Tarhini, A.; Ishizaka, A. Effect of corporate ethics and social responsibility on OCB: The role of employee identification and perceived CSR significance. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2021, 51, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, T.B.; Howard-Grenville, J.; Hampel, C.E. The company you keep: How an organization’s horizontal partnerships affect employee organizational identification. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 772–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukić, D. Strategic analysis of corporate marketing in culture management. Strat. Manag. 2019, 24, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraibar-Diez, E.; Sotorrío, L.L. The mediating effect of transparency in the relationship between corporate social responsibility and corporate reputation. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2018, 20, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Hi, N.; Blumberg, I. The Link Between (Not) Practicing CSR and Corporate Reputation: Psychological Foundations and Managerial Implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniora, J.; Pott, C. Does firms’ dissemination of corporate social responsibility information through Facebook matter for corporate reputation? J. Int. Account. Res. 2020, 19, 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, M.A.R.A.; Mohezar, S.; Yunus, N.K.M.; Ali, R.; Nazri, M. Investigating the Moderating Effect of Marketing Capability on the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Practice and Corporate Reputation in Small Medium Enterprises Food Operators. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2021, 22, 1469–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shan, Y.G.; Chang, M. Can CSR disclosure protect firm reputation during financial restatements? J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 173, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaen, V.; Demoulin, N.; Pauwels-Delassus, V. Impact of consumers’ perceptions regarding corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility in the grocery retailing industry: The role of corporate reputation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-M.; Yu, T.H.-K.; Hsiao, C.-Y. The Causal Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Reputation on Brand Equity: A Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. J. Promot. Manag. 2021, 27, 630–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berber, N.; Slavić, A.; Aleksić, M. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and corporate governance. Ekonomika 2019, 65, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berber, N.; Aleksić, M.; Slavić, A.; Jelača, M.S. The Relationship Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Reputation in Serbia. Eng. Econ. 2022, 33, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhat, K.; Anthony, R.; Shikha, J.; Makarand, P.; Vimal, B. Integrating CSR with employer branding initiatives: Proposing a model. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2021, 27, 4073–4083. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.M.; Lu, S.; Nassar, S.; Corporate Social Responsibility Metrics in S&P500 Firms’ 2017 Sustainability Reports. Rustandy Center for Social Sector Innovation, University of Chicago. 2021. Available online: https://www.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/research/sei/docs/csr-metrics-rustandy-center-report_final.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2023).

- Pérez-Cornejo, C.; de Quevedo-Puente, E.; Delgado-García, J.B. Reporting as a booster of the corporate social performance effect on corporate reputation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenhoefer, L.M. The impact of CSR on corporate reputation perceptions of the public -A configurational multi-time, multi-source perspective. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogler, D.; Eisenegger, M. CSR Communication, Corporate Reputation, and the Role of the News Media as an Agenda-Setter in the Digital Age. Bus. Soc. 2021, 60, 1957–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.S.; Dash, S.S.; Chakraborty, S.; Kumar, M. Perceived CSR and Corporate Reputation: The Mediating Role of Employee Trust. Vikalpa J. Decis. Mak. 2018, 43, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, E.; Bruno, J.M.; Sarabia-Sanchez, F.J. The impact of perceived CSR on corporate reputation and purchase intention. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 28, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Stacks, D.W. The impact of leadership style and employee empowerment on perceived organizational reputation. J. Commun. Manag. 2013, 17, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binu Raj, A. Internal branding, employees’ brand commitment and moderation role of transformational leadership: An empirical study in India telecommunication context. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2021, 14, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.D.G.M.C.; Coelho, A. The Antecedents of Corporate Reputation and Image and Their Impacts on Employee Commitment and Performance: The Moderating Role of CSR. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2019, 22, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch-Rogge, M.; Westermann, G. What really masters: Employer attractiveness in healthcare. Eurasian Stud. Bus. Econ. 2021, 18, 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Schaarschmidt, M.; Walsh, G. Social media-driven antecedents and consequences of employees’ awareness of their impact on corporate reputation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newburry, W. Dimensions, Contexts, and Levels: A Flourishing Reputation Field with Further Advancement to Come. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2017, 20, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Ponzi, L.J.; Newburry, W. Stakeholder tracking and analysis: The RepTrak® system for measuring corpo-rate reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2015, 18, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-W.; Ko, C.-H.; Huang, H.-C.; Wang, S.-J. Brand community identification matters: A dual value-creation routes framework. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto, M.; Torres, P. Effects of brand attitude and eWOM on consumers’ willingness to pay in the banking industry: Mediating role of consumer-brand identification and brand equity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Pieta, P. The Impact of Green Human Resource Management on Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification and Job Satisfaction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankins, S.; Waterhouse, J. Organizational Identity, Image, and Reputation: Examining the Influence on Perceptions of Employer Attractiveness in Public Sector Organizations. Int. J. Public Adm. 2019, 42, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, A.A.; Aman-Ullah, A.; Abjul-Majid, A.-H.B. Does employer branding facilitate the rentation of healthcare employees? A mediation moderation study through organizational identification, psychological involvement, and employee loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systemic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.; Afsar, B.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Maqsoom, A. How employees’ perceived corporate social responsibility affects employees’ pro-environmental behavior? The influence of organizational identification, corporate entrepreneurship, and environmental consciousness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kees, J.; Berry, C.; Burton, S.; Sheehan, K. An analysis of data quality: Professional panels, student subject pools, and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.; Irani, L.; Silberman, M.; Zaldivar, A.; Tomlinson, B. Who are the crwodworkers?: Shifting demographics in Mechanical Turk. In CHI’10 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrmester, M.; Kwang, T.; Gosling, S.D. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]