Responsible Leadership and Innovation during COVID-19: Evidence from the Australian Tourism and Hospitality Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Review of the Literature on Leadership and Innovation in Times of Crisis

- (1)

- Incremental innovations relate to ‘improvements within a given frame of solutions’ ([72], p. 82) and reflect variations, reconfigurations and/or upgrades of existing products or services.

- (2)

- Substantial innovations reflect a change of frame ([72], p. 82) or even mindset and involve completely new approaches that have not been pursued before. Often, they yield profound change (this can be radical or evolutionary) and transform existing business operating models and potentially lead to larger transformations in the industry.

- (3)

- Social innovations can be understood as ‘innovative activities and services that are [primarily] motivated by the goal of meeting a social need’ ([31], p. 146) and generating social value (in contrast to financial value). They have become of particular relevance in light of the UN SDGs and rising stakeholder expectations that leaders will contribute to developing solutions to social problems [32]. Social innovations, like any innovation in operations, marketing or human resource management (HRM), can be either incremental or substantial [32,38].

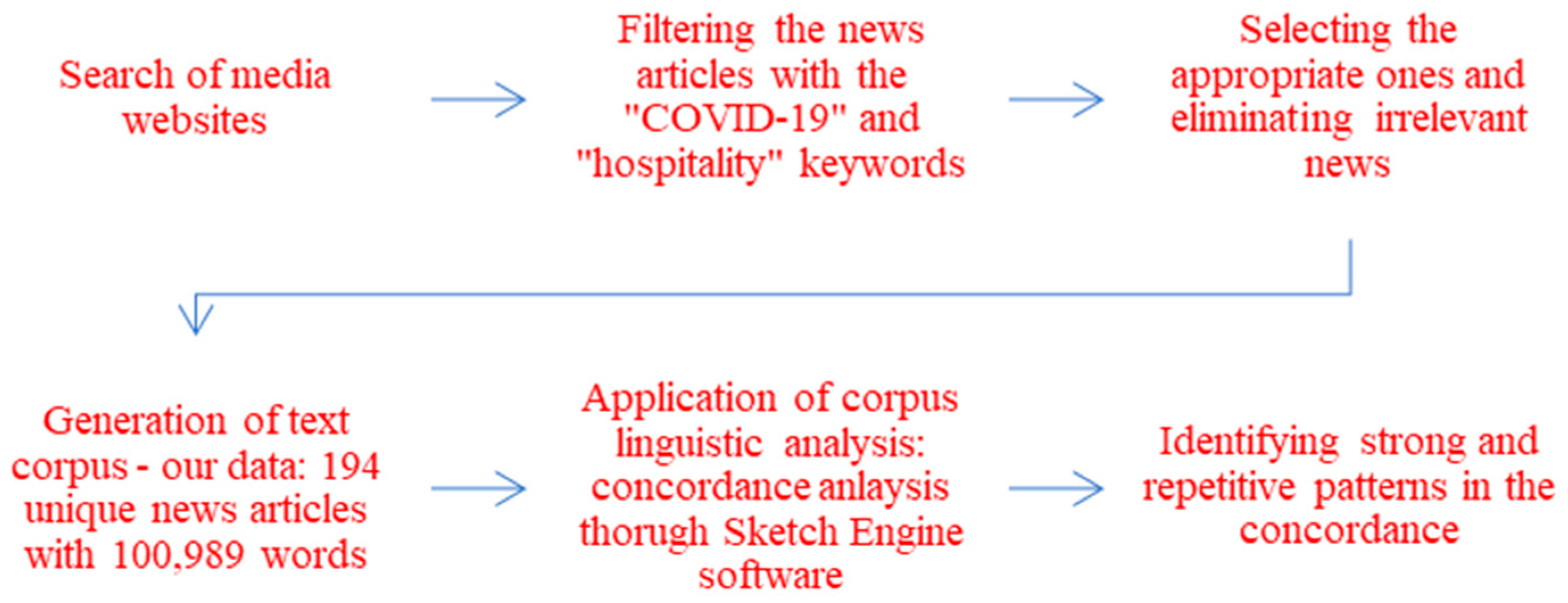

3. Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Corpus Linguistics Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Challenges Facing Hospitality Business Leaders

4.2. Leadership and Innovation as a Social Response to Challenges

5. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

5.1. Future Research Directions

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Recommendations for Policymakers

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychological Association (APA). Stress Effects on the Body, 1 November 2018. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Pham, T.D.; Dwyer, L.; Su, J.J.; Ngo, T. COVID-19 impacts of inbound tourism on Australian economy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gössling, S.; Ring, A.; Dwyer, L.; Andersson, A.C.; Hall, C.M. Optimizing or maximizing growth? A challenge for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Krittayaruangroj, K.; Iamsawan, N. Sustainable Leadership Practices and Competencies of SMEs for Sustainability and Resilience: A Community-Based Social Enterprise Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.A.; Bednall, T.; Demsar, V.; Wilson, S.G. Falling Apart and Coming Together: How Public Perceptions of Leadership Change in Response to Natural Disasters vs. Health Crises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Wei, H.; Wei, M. Exploring tourism recovery in the post-covid-19 period: An evolutionary game theory approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldwell, D.A.L.; Joosub, T.; Papageorgiou, E. Responsible leadership in organizational crises: An analysis of the effects of public perceptions of selected SA business organizations’ reputations. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, T.M. Responsible leadership and reputation management during a crisis: The cases of Delta and United Airlines. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 173, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluk, K.; Cavaliere, C.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F. A critical framework for interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six transformations to achieve the sustainable development goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G.; Amore, A. Tourism and Resilience: Individual, Organizational and Destination Perspectives; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pongsakornrungsilp, P.; Pongsakornrungsilp, S.; Jansom, A.; Chinchanachokchai, S. Rethinking Sustainable Tourism Management: Learning from the COVID-19 Pandemic to Co-Create Future of Krabi Tourism, Thailand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, E.H.; Wooten, L.P. Leadership as (un)usual: How to display competence in times of crisis. Organ. Dyn. 2005, 34, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Ramirez, G.G.; House, R.J.; Puranam, P. Does leadership matter? CEO leadership attributes and profitability under conditions of perceived environmental uncertainty. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioglu, M.A.; Van der Wal, Z. Leadership and innovation: What’s the story? The relationship between leadership support level and innovation target. Public Manag. Rev. 2022, 24, 1289–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maak, T.; Pless, N.M. Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society: A relational perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Boerner, S. Transformational leadership and team innovation: Integrating team climate principles. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1438–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elenkov, D.S.; Manev, I.M. Top management leadership and influence on innovation: The role of sociocultural context. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Agyeman, Y. Transformational leadership and innovation in higher education: A participative process approach. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2021, 24, 694–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.J.; Zhou, J. Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M.; Graen, G.B. An examination of leadership and employee creativity: The relevance of traits and relationships. Pers. Psychol. 1999, 52, 591–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Bass, B.M. Transformational leadership at different phases of the innovation process. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 1991, 2, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, T.; Chen, Y.; Carmeli, A. CEO environmentally responsible leadership and firm environmental innovation: A socio-psychological perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.A.; Borrill, C.S.; Dawson, J.F.; Brodbeck, F.C.; Shapiro, D.A.; Haward, B. Leadership clarity and team innovation in health care. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L. Tourists’ perceptions of environmentally responsible innovations at tourism businesses. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgan, G. The process of social innovation. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, N.M.; Murphy, M.; Maak, T.; Sengupta, A. Societal challenges and business leadership for social innovation. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2021, 16, 535–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Voegtlin, C. Corporate governance for responsible innovation: Approaches to corporate governance and their implications for sustainable development. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 182–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar Am, J.; Furstenthal, L.; Jorge, F.; Roth, E. Innovation in a Crisis: Why It Is More Important than Ever; 17 June 2020; McKinsey & Co.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/innovation-in-a-crisis-why-it-is-more-critical-than-ever# (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Visentin, M.; Reis, R.S.; Cappiello, G.; Casoli, D. Sensing the virus: How social capital enhances hoteliers’ ability to cope with COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breier, M.; Kallmuenzer, A.; Clauss, T.; Gast, J.; Kraus, S.; Tiberius, V. The role of business model innovation in the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 crisis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kang, J. Reducing perceived health risk to attract hotel customers in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Focused on technology innovation for social distancing and cleanliness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maak, T.; Pless, N.M.; Voegtlin, C. Business statesman or shareholder advocate? CEO responsible leadership styles and the micro-foundations of political CSR. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 463–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavik, Y.L.; Shao, B.; Newman, A.; Schwarz, G. Crisis leadership: A review and future research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2021, 32, 101518. [Google Scholar]

- James, E.H.; Wooten, L.P.; Dushek, K. Crisis management: Informing a new leadership research agenda. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 455–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, J.; Pfarrer, M.D.; Short, C.E.; Coombs, W.T. Crises and crisis management: Integration, interpretation, and research development. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1661–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herédia-Colaço, V.; Rodrigues, H. Hosting in turbulent times: Hoteliers’ perceptions and strategies to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, E.; Kizildag, M.; Ridderstaat, J. Financial recovery strategies for restaurants during COVID-19: Evidence from the US restaurant industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuñiga-Collazos, A.; Harrill, R.; Castillo-Palacio, M.; Padilla-Delgado, L.M. Negative effect of innovation on organizational competitiveness on tourism companies. Tour. Anal. 2020, 25, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Gao, Y.L.; McGinley, S. Updates in service standards in hotels: How COVID-19 changed operations. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1668–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, T.; Hua, N. Transcending the COVID-19 crisis: Business resilience and innovation of the restaurant industry in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 49, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organizations, 8th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.; Lee, T.S.; Lee, H.M.; Wang, J. The Influence of Responsible Leadership on Strategic Agility: Cases from the Taiwan Hospitality Industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foldøy, S.; Furunes, T.; Dagsland, Å.H.B.; Haver, A. Responsibility beyond the Board Room? A Systematic Review of Responsible Leadership: Operationalizations, Antecedents and Outcomes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, C.; Gonçalves, J. The Relationship between Responsible Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Hospitality Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yan, X. How Responsible Leadership Motivates Employees to Engage in Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: A Double-Mediation Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Islam, N.; Samrat, N.H.; Dey, S.; Ray, B. Smart Farming through Responsible Leadership in Bangladesh: Possibilities, Opportunities, and Beyond. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Zhang, H. Improving Millennial Employee Well-Being and Task Performance in the Hospitality Industry: The Interactive Effects of HRM and Responsible Leadership. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xu, W.; Cai, S.; Yang, F.; Chen, Q. Does top management team responsible leadership help employees go green? The role of green human resource management and environmental felt-responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuecheng, W.; Ahmad, N.H.; Iqbal, Q.; Saina, B. Responsible Leadership and Sustainable Development in East Asia Economic Group: Application of Social Exchange Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Guo, X. Antecedents of Responsible Leadership: Proactive and Passive Responsible Leadership Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q. Exploring the Impact of Responsible Leadership on Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: A Leadership Identity Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, B.; Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; De Colle, A.C. Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 3, 403–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, N.M. Understanding responsible leadership: Role identity and motivational drivers. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Quigley, N.R. Responsible leadership and stakeholder management: Influence pathways and organizational outcomes. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Pache, A.-C.; Sengul, M.; Kimsey, M. The dual-purpose playbook. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 97, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Pless, N.M.; Sengupta, A.; Wheeler, M.; Maak, T. Responsible Leadership and the Reflective CEO: Resolving Stakeholder Conflict by Imagining What Could be Done. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 180, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maak, T.; Pless, N.M.; Wohlgezogen, F. The fault lines of leadership: Lessons from the global Covid-19 crisis. J. Change Manag. 2021, 21, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, J.W.; Banerjee, B.; Matson, P. A core curriculum for sustainability leadership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pless, N.M.; Maak, T. Responsible leadership: Pathways to the future. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C. Development of a scale measuring discursive responsible leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C. What does it mean to be responsible? Addressing the missing responsibility dimension in ethical leadership research. Leadership 2016, 12, 581–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, M.G.; Piva, E.; Quas, A.; Rossi-Lamastra, C. How high-tech entrepreneurial ventures cope with the global crisis: Changes in product innovation and internationalization strategies. Ind. Innov. 2016, 23, 647–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Hallak, R.; Sardeshmukh, S.R. Innovation, entrepreneurship, and restaurant performance: A higher-order structural model. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Shin, H.; Santa-María, M.J.; Nicolau, J.L. Hotels’ COVID-19 innovation and performance. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 88, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A.; Verganti, R. Incremental and radical innovation. Des. Issues 2014, 30, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, E.H.; Wooten, L.P. Diversity crises: How firms manage discrimination lawsuits. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1103–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, J.; Cradock-Henry, N.; Buelow, F.; Rennie, H. Agrifood tourism, rural resilience, and recovery in a postdisaster context: Insights and evidence from Kaikōura-Hurunui, New Zealand. Tour. Anal. 2021, 26, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, M.; Mair, H. Blogging slum tourism: A critical discourse analysis of travel blogs. Tour. Anal. 2016, 21, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Wong, I.A. Strategic crisis response through changing message frames: A case of airline corporations. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2890–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C. A war of words: A linguistic analysis of BBC embedded reports during the Iraq conflict. In Discourse and Contemporary Social Change; Fairclough, N., Cortese, G., Ardizzone, P., Eds.; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 119–140. [Google Scholar]

- Hunston, S. Corpora in Applied Linguistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, J. Corpus, Concordance, Collocation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pollach, I. Taming textual data: The contribution of corpus linguistics to computer-aided text analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2012, 15, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Haj, M.; Rayson, P.; Walker, M.; Young, S.; Simaki, V. In search of meaning: Lessons, resources and next steps for computational analysis of financial discourse. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2019, 46, 265–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, A.; Huault, I. The maintenance of macro-vocabularies in an industry: The case of France’s recorded music industry. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 80, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, Y. Comparative analysis of mission statements of Chinese and American Fortune 500 companies: A study from the perspective of linguistics. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, C.; Nowak, V.; Howorth, C.; Southern, A. Multipartite attitudes to enterprise: A comparative study of young people and place. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020, 38, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giritli Nygren, K.; Klinga, M.; Olofsson, A.; Öhman, S. The language of risk and vulnerability in covering the COVID-19 pandemic in Swedish mass media in 2020: Implications for the sustainable management of elderly care. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, K.; Gnoth, J.; Mather, D. Tourists’ participation on Web 2.0: A corpus linguistic analysis of experiences. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkington, K.; Stanford, D.; Guiver, J. Discourse(s) of growth and sustainability in national tourism policy documents. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1041–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Wong, I.A.; Huang, G.I. The coevolutionary process of restaurant CSR in the time of mega disruption. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P. ‘Bad wigs and screaming mimis’: Using corpus-assisted techniques to carry out critical discourse analysis of the representation of trans people in the British press. In Contemporary Critical Discourse Studies; Hart, C., Cap, C., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2014; pp. 211–235. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, P.; Gabrielatos, C.; Khosravinik, M.; Krzyzanowski, M.; McEnery, T.; Wodak, R. A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse Soc. 2008, 19, 273–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayson, P. Computational tools and methods for corpus compilation and analysis. In The Cambridge Handbook of English Corpus Linguistics; Biber, D., Reppen, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne, M. Searching and concordancing. In Corpus Linguistics: An International Handbook; Lüdeling, A., Kytö, M., Eds.; Walter De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 706–737. [Google Scholar]

- Gilfillan, G. COVID-19: Impacts on Casual Workers in Australia—A Statistical Snapshot, 8 May 2020. Parliamentary Library. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1920/StatisticalSnapshotCasualWorkersAustralia (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Williams, C.C.; Kayaoglu, A. COVID-19 and undeclared work: Impacts and policy responses in Europe. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 914–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.B.; Ullah, S.M.; Choi, S.B. The mediated moderating role of organizational learning culture in the relationships among authentic leadership, leader–member exchange, and employees’ innovative behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, V.; Srivastava, S. Hospitality and tourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on challenges and learnings from India. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.C. Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on Europe’s tourism industry: Addressing tourism enterprises and workers in the undeclared economy. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 23, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhan, M.; Salam, M.T.; Abou Hamdan, O.; Tariq, H. Crisis management in the hospitality sector SMEs in Pakistan during COVID-19. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 98, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Siegel, D.S. Theoretical and practitioner letters: Defining the socially responsible leader. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, D.A.; Siegel, D.S.; Stahl, G. Defining the socially responsible leader: Revisiting issues in responsible leadership. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2020, 27, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakey, B.; Vander Molen, R.J.; Fles, E.; Andrews, J. Ordinary social interaction and the main effect between perceived support and affect. J. Personal. 2016, 84, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ham, S. Restaurants’ disclosure of nutritional information as a corporate social responsibility initiative: Customers’ attitudinal and behavioral responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Conklin, M.; Cranage, D.; Lee, S. The role of perceived corporate social responsibility on providing healthful foods and nutrition information with health-consciousness as a moderator. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unilever. Unilever Food Solutions Joins #EatAloneTogether Movement. [Media Release], 4 May 2020. Available online: https://www.unilever.com.au/news/press-releases/2020/unilever-food-solutions-joins-eatalonetogether-movement.html (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Maak, T. Stoetter Social entrepreneurs as responsible leaders: “Fundación Paraguaya” and the case of Martín Burt. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.S.; Morrison, A. The Global Leadership Challenge; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moyle, B.D.; Weaver, D.B.; Gössling, S.; McLennan, C.-L.; Hadinejad, A. Are water-centric themes in sustainable tourism research congruent with the UN Sustainable Development Goals? J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1821–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Marin, J.; Tops, M.; Manzanera, R.; Piva Demarzo, M.M.; de Mon, M.Á.; García-Campayo, J. Mindfulness, resilience, and burnout subtypes in primary care physicians: The possible mediating role of positive and negative affect. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, M.; Haar, J.M.; Luthans, F. The role of mindfulness and psychological capital on the well-being of leaders. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Website | Number of News Articles | Total Number of Words |

|---|---|---|

| Hospitality Directory (hospitalitydirectory.com.au, accessed on 10 June 2020) | 71 (36.6%) | 18,485 (18.3%) |

| The Hotel Conversation (thehotelconversation.com.au, accessed on 10 June 2020) | 46 (23.7%) | 23,735 (23.5%) |

| ABC News (abc.net.au, accessed on 10 June 2020) | 38 (19.6%) | 26,964 (26.7%) |

| Gourmet Traveller (gourmettraveller.com.au, accessed on 10 June 2020) | 18 (9.3%) | 21,814 (21.6%) |

| 9 News (9news.com.au, accessed on 10 June 2020) | 11 (5.7%) | 5400 (5.3%) |

| Business News Australia (businessnewsaus.com.au, accessed on 10 June 2020) | 10 (5.2%) | 4586 (4.5%) |

| Total | 194 | 100,984 |

| Challenges | Selected Examples of Challenges (Business Challenges Underlined, Mental Highlighted) Occurring in Concordance Lines |

|---|---|

| Business: Financial loss Mental health: Depression, suicide | <s>it’s been pretty depressing thinking about how much income we’ve lost since March<s> <s>I know of two business owners who had taken their lives because of the toll coronavirus had on their business. Their financial losses have just ruined their lives<s> |

| Business: Survival and development Mental health: Pessimistic attitude | <s>up to 30% of restaurants may never reopen after the coronavirus shutdown ends<s> |

| Business: Staffing Mental health: Helplessness | <s>For the hospitality industry, working from home is not an option. Chefs, baristas and front-of-house staff cannot tele-conference their livelihoods. A restaurant cannot operate remotely<s> |

| Business: Reduction of customer base Mental health: Distress and adverse reaction | <s>no-show diners have been warned there is a ‘special place in hell’ for them<s> |

| Business: Health and safety concerns Mental health: Stress and related long-time consequences | <s>The current pandemic is a pressure-cooker environment that only exacerbates their existing physical and mental health issues.<s> |

| Innovative Directions | Innovation Example |

|---|---|

| Product innovation | Restaurants/cafes turning into groceries, bakeries |

| Service innovation | Take-away, home deliveries |

| Marketing and sales innovation | Using internet/websites for restaurants sales, buy now stay later campaigns for hotels |

| Management innovation | Re-employing some staff as delivery workers |

| Process innovation | Contactless food delivery systems, |

| Social innovation | Turning hotels into hospitals, free rooms for healthcare workers or for those who are in need |

| Innovation Type and Definition | Incremental Innovation—A Variation in Organisational Routines and Practices | Substantial Innovation—A Fundamental Change in Organisational Practices |

|---|---|---|

| Product innovation—a new or improved good that has been presented to customers | The restaurant has since transitioned to elegant take-home dinners for two and holds popular bake sales on the weekend. They’re doing boutique produce boxes, heat-at-home Vietnamese meals of pho and vermicelli salad, and takeaway banh mi | has turned the front bar into a bottle shop and grocer, selling bread, meat and fruit. Instagram description has changed from ‘restaurant’ to ‘shopping and retail’, and it will operate as such for the following months out of necessity. Coffee shop owners shift the whole model into more of a grocer the owners of Tanaka coffee shop in Melbourne’s Carlton are selling boxes of fresh produce sourced from a range of local suppliers that can be picked up from the store or home delivered Brae made moves towards offering house-made loaves of bread and fresh produce boxes harvested from its own farm, it advertised exclusively through Birregurra’s Facebook group By Thursday, the chef-owner announced Navi’s take-home meal service. By Saturday, it was also operating as a weekend bakery. head chef worked 20-h days to convert the restaurant operations into a wood-fired bakery But the owner has risen to the occasion by converting the cellar door space into a grocer, food delivery and wine takeaway hub. They’ve installed a bread oven to ramp up their sourdough bread production |

| Service innovation—a new or improved service that has been presented to customers | has switched his business strategy to open earlier, starting at 5 pm … families will come to the earlier seating, … each session will also be timed, and diners will have around one-and-a-half hours to order and eat their meal before a second seating begins at 7 pm We’ve changed our whole set up in the cafe to suit takeaway service and it’s working well a night market venue … has adapted to restrictions by converting its laneway to a drive-through, headlined by drag queens He has offered free takeaway delivery to entice customers Son has been doing home deliveries via bicycle, in addition to the restaurant’s takeaway menu and take-home frozen packs of kimchi jjigae [spiced Korean stew] and mandu, complete with stylised how-to-prepare at-home video instructions. we learned from our mistakes, and this weekend, we did 250 deliveries Selling takeaway tap beer is a big break with pub tradition, but it will help ensure cashflow as we bunker down and try to see this crisis out and keep as many staff employed as possible sous chef has compiled a restaurant-friendly playlist too: Paul Kelly for lunch, uptempo Motown for dinner. Filling up $10 take-home growlers is keeping us alive right now have launched their at-home menus to be picked up from Yellow in Potts Point or delivered to addresses within a six-kilometre range of the suburb the neighbourhood café made its full menu available for takeaway The Asian pasta restaurant has set up a purpose-built trolley to allow contactless takeaway orders. We have increased our level of social engagement, delivering our club communities with daily activities to help keep their passion for travel ignited. This has included travel quizzes, sharing best travel movie ideas, Lego competitions, cutest pet competitions and more. The website also provides them with some fun distractions for all the family during isolation, such as activities and games, many which are travel-orientated. We know that cabin fever can be especially tough for the younger members of the family, so we are also providing them with travel-inspired, colouring-in pages and activities to help keep kids entertained while our timeshare owners (including many families with small children) are staying home and counting down to their next holiday. the leadership team made the pre-emptive move to ensure physical distancing and only serve takeaway meals to patrons | by using the hashtag #EatAloneTogether, people can keep celebrating those special moments and share meals together, but through digital connectivity to still allow them to have family and friends over for dinner Our recent initiative of our Social Hour cocktail trolley, which brings the bar to our guests’ rooms, has been loved and is an example of how we constantly adapt to ensure we are still delivering an effortless experience. restaurant has taken the extraordinary step of closing their dine-in business and operating exclusively on food delivery and takeaway trade restaurant has placed cardboard cut-outs at empty tables to stop diners from feeling lonely while they eat. To add to the busy restaurant vibe, the owner also plans to play guest chatter We have looked to see whether we can tap into a different type of market—that being a furnished flexible lease of up to 12 months I’ve effectively had to start a brand new business, delivery isn’t something I’ve done before has pivoted to a home dining service as it battles to stay afloat during the coronavirus lockdown We have looked to see whether we can tap into a different type of market—that being a furnished flexible lease of up to 12 months |

| Marketing and sales innovation—(e.g., a new sales channel) | buy now stay later scheme’ introducing an $80 cancellation fee for no-shows or cancellations less than 24 h before the booking time … takes payment in advance to secure bookings at the restaurant announcing a special dining package: Up to 10 people can book out the venue for four hours for a group fee of $1000 implemented a credit card fee on booking that was only charged if the diners did not turn up An $80 per person set menu, excluding drinks, is on offer one hotel in Sydney is looking to attract executives tired of working from home Hotel in Potts Point is offering customers a ‘Remote Office Day Package’ from between 8 am to 6 pm bookings are only taken via phone and email in order to create a personal connection with diners even before they step in the restaurant To secure a seat at the Bondi wine bar, diners, in groups of 10, must book out the whole venue. | Project Unity lets venues in any local community form an alliance and cross-promote to each other’s audiences … ‘venues, which were once competitors, are now helping each other cross-promote to their customers and generate takeaway/delivery transactions’ I was just sitting down reading the paper, and I realised there is a pretty big market here for customers to order in advance and select a delivery time that works for them, which means businesses aren’t inundated with orders all at once … In building the business from scratch … the website is set to go live on Monday #LocalNightIn initiative—a new national listing database featuring Australian venues that are providing delivery and takeaway options during this time chef is launching his new food delivery platform Providoor on June 1 with the lockdown, we’ve had to adapt pretty quickly, moving to … Canberra Eats (canberraeats.com, accessed on 10 June 2020-an online restaurant meal ordering service) The Vietnamese restaurant chain has launched a new online ordering platform All restaurants within the precinct are still cooking up your favourite dishes, and now you will be able to use the app to browse their menus, pre-order, pay and pick them up all on one simple and easy-to-use platform |

| Management innovation (e.g., solutions in HRM, accounting, finance, etc.) | we commenced temperature checks of all employees on their arrival to work We have regular Zoom meetings with all teams, and in addition to email communication and video messaging, we have set up a closed user Facebook group for all employees (The restaurant has since transitioned to elegant take-home dinners for two and holds popular bake sales on the weekend) The new model has been enough to keep all its kitchen and front-of-house staff employed. | the small brigade of chefs and front-of-house staff have turned into bakers and assistant gardeners—it’s a means to keep staff employed A lot of restaurants like mine will start employing our own drivers for delivery Restaurant Labart has delegated front-of-house staff as delivery drivers our staff are like family—they’re all locals with cars. Instead of working on the floor, they’ll be delivering to the door |

| Process innovation—novel solutions in production, technology and management | implementing a 72-h cancellation policy to cover the full cost of the $120 set menu for those who don’t honour their reservations introducing an $80 cancellation fee for no-shows or cancellations less than 24 h before the booking time decided to open from Thursday to Saturday only, starting this Thursday introduced a contactless pick-up system to reduce person-to-person contact between customers and staff. | |

| Social innovation—novel solutions that aim to improve the well-being of society while increasing the effectiveness of use of resources | A restaurant in Melbourne’s Southbank is screening the temperatures of all their customers before they enter opening six days a week for takeaway and take-home meals, staffed by just the two of them. The decision to stay open was driven by community needs. ‘There are people [in this suburb] who live on their own, and we’re the only people they see that day survival menu’: ‘It’s about providing food that ensures I can pay my wages, and people who have lost their jobs can still afford to feed themselves. It’s not just survival for ourselves. It’s for everyone else AVC has instead decided to put its team and resource to work through a number of initiatives, including dishing up free meals for staff and $3 meals to other hospitality workers as well as supporting its visa workers not entitled to Government assistance. launching a unique cleanliness and prevention label: ALLSAFE his two venues … will give free feeds to those people hardest hit by the coronavirus … We just want to look after our local community because you look after us. She’s made up packs of lasagne for customers with immuno-compromised conditions who would arrive at the restaurant fully kitted out in gloves and masks; she’s cooked takeaway for a couple who live around the corner in an apartment with no stove, no microwave It took just two days for social-enterprise restaurant Colombo Social in Newtown to repurpose its cooking facilities into a production kitchen that provides free meals for those in need. A no-handshakes, no-hugs and no-high fives policy between customers and staff will also be enacted … We’re a public place, and with a lot of foot traffic, and we have a responsibility to do something Coburg kitchen is also selling bags of flour to customers who are experiencing difficulty sourcing it due to panic-buying in supermarkets. | hotels acting as ‘medi-hotels’, where operators work in conjunction with the health department and the government to provide rooms where people can recover Opening hotel’s doors to victims of ‘domestic violence dedicating a floor of the hotel to offer relief and a safe space to those in need. People can support their local by visiting loveofyourlocal.com.au and nominating their favourite venue, then buying a pint of CUB beer using their credit card or PayPal account, with the cash going to the venue directly. Quest Apartment Hotels has teamed up with Housing All Australians and the Salvation Army to provide temporary accommodation for Australians that are at risk of homelessness. Due to this crisis, we know thousands of people have lost their jobs and are struggling to pay rent, we know domestic violence is on the rise, and we know these situations can lead to homelessness, he said. holding 20 rooms every night free of charge for healthcare workers at nearby hospitals who may need extra support or a safe place to sleep close by. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yildiz, M.; Pless, N.; Ceyhan, S.; Hallak, R. Responsible Leadership and Innovation during COVID-19: Evidence from the Australian Tourism and Hospitality Sector. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064922

Yildiz M, Pless N, Ceyhan S, Hallak R. Responsible Leadership and Innovation during COVID-19: Evidence from the Australian Tourism and Hospitality Sector. Sustainability. 2023; 15(6):4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064922

Chicago/Turabian StyleYildiz, Mehmet, Nicola Pless, Semih Ceyhan, and Rob Hallak. 2023. "Responsible Leadership and Innovation during COVID-19: Evidence from the Australian Tourism and Hospitality Sector" Sustainability 15, no. 6: 4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064922

APA StyleYildiz, M., Pless, N., Ceyhan, S., & Hallak, R. (2023). Responsible Leadership and Innovation during COVID-19: Evidence from the Australian Tourism and Hospitality Sector. Sustainability, 15(6), 4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15064922