Abstract

This study aims to comprehensively evaluate the sustainable impact of FDI on the development of host African countries. Previous empirical studies seem to have overestimated the impact of FDI by limiting its effects to one aspect or sub-aspect of sustainable development. This study focuses on the sustainable/net effect of FDI on development in Africa. To achieve this, a multidimensional model that combines two opposing views (mainstream theory of economic development and dependent theory) was tested. Panel data of 35 African countries with the PMG/ARDL approach were used to probe the sustainable effect of FDI from 1990 to 2020. The key findings of this study reveal that the overall estimated sustainable effect of FDI on real GDP per capita is statistically minuscule for the entire sample. Thus, the effect of FDI on the development of host African countries is not inherently more important. The most striking result that emerged from the data is that environmental degradation is the dominant variable that adversely influences overall development in Africa. Another striking finding that emerged from the data is that income inequality, in general, has a significant negative impact on real GDP per capita in the long run. More importantly, the results of this study confirm that CO2, GINI, and GOV play important roles in the relationship between FDI and African development. Estimates of the error correction term for each specific country are negative and statistically significant. The fastest speed of adjustment was observed in Morocco, while the lowest was recorded in South Africa. Furthermore, this study presents different policy implications based on the long-term results.

1. Introduction

The effect of foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries has become the most dominant subject of interest in international economics, business studies, and the political community. This is due to the belief that FDI is an important source of external finance for sustainable development in all host economies, especially in developing economies [1,2]. This self-evident fact came just after the debt crisis of the 1980s when other sources of external financing in developing economies became scarce or unstable [3,4]. The recourse to external borrowing has been limited for most developing countries because of their levels of indebtedness. Additionally, developmental aids such as the one promised at the International Conference on Financing for Development held in Monterrey, Mexico, in 2002, were slow to be materialized and remained insufficient and volatile [5].

With the transition to open economies, developing countries are recognizing the potential of FDI for their economies and sustainable development [3]. Currently, FDI is the largest non-debt source of external financing for these countries [6], larger than official development assistance and transfer of funds or investment flows into the portfolio [7,8]. Lewis [9] articulated that there is no country, including England, Japan, Russia, or the USA, where foreign investments did not have a considerable developmental influence in their embryonic stage of development. Again, following the success of newly emerging states, such as Malaysia and Singapore, there has been an impetus for developing countries to engage intensively in activities that aim at luring more incoming FDI flows. Thus, the desire for FDI by developing countries is conditioned by its anticipated sustainable impact on development [10]. The concept of sustainable development (SD) refers to achieving optimization of economic growth, environmental protection, income redistribution, and responsible institutions.

FDI is expected to impact sustainable development in host countries by transferring technologies and upgrading skills desperately needed in developing countries, including African countries. Its impact on sustainable development stems from the deployment by multinational corporations of a “bundle of assets” that are scarce in developing countries, including technology, management skills, R&D capacities, and brand names [11]. According to Zarsky (2005), FDI led by transnational corporations (TNCs) transfers greater technology and management skills, stimulates domestic investment and growth, generates efficiency spill-overs, and integrates developing countries’ companies into global markets [12]. Thus, FDI is a powerful international mechanism for mobilizing tangible and intangible assets (capital, technology, skills, access to markets, etc.) that are essential for sustainable development in host developing countries [13]. Therefore, developing countries are benefiting from increased foreign investment by boosting their overall production capacity. FDI can also boost sustainable development by promoting competition and innovation and improving a country’s export performance (WWF-UK 2000). All of this underpins the efforts of developing countries to achieve sustainable development and ensure the rights of future generations to the available natural resources.

As a result, African economies, like many other developing economies around the world, have initiated domestic reforms towards the rest of the world. Many of these economies have even gone out of their way to offer tax incentives and subsidies, lifting controls on capital and on the repatriations of dividends in the past to attract more incoming FDI flows. The economic rationale for providing incentives often stems from the fact that some developing countries take the sustainable development impact of FDI for granted [14,15,16,17]. Therefore, attractiveness is more important when considering Africa’s long-term development deficit and the need to meet sustainable development goals (SDGs) [18]. These views are based primarily on the liberal school, specifically on the endogenous model, and were developed in the literature review section of this study.

Although the above reforms and stimulus measures fell short of reformers’ expectations (as Africa is the least benefited from global FDI flows), FDI trends in African countries are encouraging [19]. According to Chen, Geiger, and Fu (2015), FDI in Africa is relatively high compared to the past and more diverse than ever [19]. However, these trends have recently been severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, making it difficult to attract and sustain FDI in developing countries [20,21]. For example, at the end of March 2020, it was observed that USD 83 billion was withdrawn from developing economies by foreign investors as the COVID-19 crisis began; this is the largest capital outflow ever recorded [22]. As a result, policymakers in developing nations will have to work hard to design and implement further reforms to effectively attract and retain productive foreign investments.

The literature on the presence of FDI In host developing economies concludes that FDI results not only in economic progress (welfare increasing) but also in welfare decreasing by worsening environmental crisis [23,24,25,26,27,28,29], perpetuating income inequality [30,31,32,33], and eroding national sovereignty [9,34,35,36], which, in turn, undermine both the economic progress and development prospects of these economies [1]. Thus, the success of FDI as an engine for welfare increasing (economic development) is materialized at the expense of environmental and social costs [37]. Surprisingly, some scholars have shown that foreign-owned firms influence environmental policy, but the scale of this influence hinges on the level of the corruptibility of the local government in host developing countries [38]. These problems arise because FDI is poorly regulated, and countries resort to self-harm to attract such investments [3].

As this brief description shows, FDI has economic, social, environmental, and political impacts that are fundamental aspects of sustainable development. In fact, a developing countries’ appetite for FDI is conditioned by their expected impact on sustainable development (that is, relief from economic, social, environmental, and political downturns). Therefore, environmental, social, and political aspects need to be taken into account when assessing the sustainable impact of FDI on the development of host developing countries. As a matter of fact, scholars have emphasized that both welfare-increasing and decreasing (adverse) effects of FDI should be given equal attention in the analyses of its effect in host developing countries [10].

Therefore, this study aims to comprehensively evaluate the effect of FDI as a sustainable development potential on host African countries’ development. According to OECD (2002), the sustained impact of FDI on the development of host developing countries entails shedding light on the second question, specifically the overall/net impact of FDI on the development of these countries [39]. To achieve this, a multidimensional model that fully/perfectly captures the double-edged nature of FDI in developing countries has been proposed and tested. Previous empirical studies appear to overestimate the impact of FDI by limiting it to one aspect or sub-aspect of sustainable development. In particular, these studies focus more on the economic and environmental aspects of sustainable development. These studies are important but provide partial impact. This is because sustainable development is not framed by economic, social, environmental, or political dimensions disjointedly [40] but, rather, by a system that includes all four aspects of sustainable development. Therefore, the literature on the sustainable/actual impact of FDI on African host countries is incomplete. Tvaronavičienė and Lankauskienė [10] emphasized that the scope of sustainable development entails both processes and policies by which countries expand the economic, social, environmental, and political (institutional) wellbeing of their people and is valid for both the Global North and the Global South.

Thus, this study was motivated by the apparent lack of empirical literature on the sustainable effect of FDI on African economies. Bissoon [41] agreed with the view that insights on FDI as a catalyst of sustainable development are seriously lacking in Africa. It is these gaps that make this article so timely and relevant. Africa, which is different from other continents, being the world’s poorest, has relied on the sustainable development potential of FDI over the past 30 years to overcome these challenges and achieve sustainable development. We believe it is very important to evaluate whether FDI is really important in making these lofty dreams a reality. The findings of this study may prompt policymakers in African countries to rethink and restructure specific strategies to condition entry or enhance the potential sustainable impact of FDI. The following is the research question arising from the above discussion: is the sustainable effect of FDI on the development of host African countries inherently more important?

This study contributes to the FDI and development literature in the following ways: First, this paper enriches the research method of the existing literature. Heterogeneous dynamic panel data modeling, also known as the panel, auto-regressive distributed lag (ARDL) modeling approach selected for the model, resolves the endogeneity problem while breaking through the constraints of the same order of integration among the variables under consideration. Second, while previous empirical studies seem to overestimate the impact of FDI, limiting it to one aspect or sub-aspect of sustainable development, this study provides comprehensive evidence on the sustainable development potential of FDI in African host countries. In this way, this study extends the analysis from fractional to sustainable/net impact of FDI on the host African countries’ development. Third, a multidimensional model that fully/perfectly captures the double-edged nature of FDI in developing countries is proposed and tested in this study. Finally, unlike previous empirical studies that considered both developed and developing countries, this study focused only on African countries, as justified previously.

An empirical analysis of the present study, using a method that has substantial advantages over other co-integration methods and panel data from 35 African countries, provides several results that suggest that, in a sustainable manner, FDI contributes too little to African countries’ development. This implies that FDI is not inherently an important determinant of development in Africa. The results also indicate that CO2 exerts a dominant and detrimental effect on the development of this continent.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Literature

Different schools of thought have put forward different theories about the effects of FDI on the host country’s welfare. In this article, we will try to identify the causes of development or underdevelopment by looking at the three most commonly used schools of thought in the literature on this issue. These include neoclassical and endogenous models of growth and dependency theories. While neoclassical and endogenous growth models (mainstream economic growth theory) mainly serve as the basis for empirical literature on welfare increasing effect of FDI on host countries, dependency theories advance its critiques (welfare-decreasing effects) on modernization theory. A review of the theoretical literature makes it clear that FDI is a double-edged sword. This is because FDI can simultaneously increase and decrease the welfare of the host developing country. Many scholars have confirmed this claim, as shown in the empirical literature review section of this paper. Though the welfare-increasing effects of FDI are mostly analyzed within the framework of the mainstream economic growth theory, the welfare-decreasing effects are analyzed within the framework of dependency theories [42], as will be demonstrated in the following paragraphs. First of all, the neoclassical theory developed by Solow [43] and Swan [44] suggests that FDI can simply replenish the host country’s physical capital stock. Therefore, an increase in the physical capital stock through foreign direct investment accelerates economic growth, resulting in an increase in output per capita, but only in the short term. This is because declining returns on physical capital ultimately force growth in the host economy onto a new, equilibrium growth path where per capita output growth depends only on exogenous variables such as technological progress. Therefore, according to this theory, FDI is expected to only exert a level effect in host countries.

The failure of neoclassical models to answer the central question of this paper calls for further exploration of theories that account for diverse externalities to overcome the limitations of neoclassical models of exogenous technological progress. The endogenous growth model does this by loosening assumptions about one type of capital (physical capital). Endogenous growth theorists such as Lucas [45,46] and Romer [47,48] argue that technological change through research and development (R&D) investment and knowledge-intensive change through schooling or learning-by-doing are key long-term developments.

According to this theory, incoming FDI flows can respond appropriately to the host country’s long-term economic development prospects by providing all kinds of development ingredients to the host developing country. Ozawa [46] hypothesized that FDI serves to create and provide technology, knowledge, and connections with the host economy. These theories assume that FDI is more efficient than domestic investment because it integrates new technologies into production functions. As a result, attracting FDI is becoming a key element in almost all developing countries’ development plans. However, the endogenous growth model does not provide a sufficient answer to the central question of this article. This is because the effect of FDI extends to all aspects of sustainable development, whereas endogenous growth models are limited to the economic aspect or direct (capital expansion) and indirect economic effects (capital deepening).

As the brief description above suggests, mainstream economic development theory overlooks the adverse effects of FDI on environmental crises and income inequality, as well as political subordination, which poses serious development challenges in developing countries. These limitations give way to multidimensional models that consider the adverse effects of FDI on other aspects of sustainable development, thus providing a comprehensive theoretical framework for assessing the sustainable impact of FDI in host developing countries. For this reason, in addition to the mainstream theory of economic development, this study drew from dependency theory. Sustainable development recommends a balanced approach to growth, taking into account social, economic, environmental, and institutional dimensions.

Dependency theorists opine that all the ills of developing countries are a product of historical and continuing incoming capital flows coupled with the political intervention of developed countries. The process under which this occurs is through imperialistic tactics whereby developing countries have to produce low-end products, including food and raw materials, which are made available to developed countries for further industrialization [48]. In the end, high-value consumer goods must flow back to developing countries. This justifies the eagerness of developed countries to prevent developing countries from achieving genuine and autonomous development and their determination to foster endless dependence on developing countries. The literature indicates that MNEs and Washington consensus organizations with elites in developing countries are generally key agents to the flourishing of this dependency system for their own benefits [49]. Thus, relying on FDI would lead to disastrous outcomes; otherwise, how can income inequality between countries be elucidated today? Indeed, it is odd that income inequality between the Global South and the Global North is deep, while the relationship between the two has been there for many years. A more recent study by Chukwu and Ituma [50] posits that “African states must have been trapped into idealistic development strategies”. A miracle cure suggested by dependency theorists is to encourage “local class relationships and not the other way round”.

Economic literature concludes that FDI carries both costs and benefits to host developing countries. However, existing models that capture the effect of FDI on host developing countries, namely, mainstream economic theory or dependence models, do not simultaneously cover both benefits and costs. They either cover costs (case of dependency theories) or benefits (liberal theories). Thus, to our knowledge, there is no single comprehensive model in the empirical literature that integrates the whole range of consequences of FDI on host developing countries. Therefore, all available evidence is partial, skewed, and unreconciled. This is the gap in the theoretical literature that this article has attempted to bridge. To do so, a multidimensional model that integrates the double-edged nature of FDI in developing countries was proposed and tested. Recent studies such as that of Tvaronavičienė and Lankauskienė [10] weighed on this view that both the costs and benefits of FDI should be combined in a single framework to provide a more comprehensive picture of the welfare effect of FDI on the development of host developing countries.

2.2. Empirical Literature

The effect of FDI on sub-aspects of sustainable development of host developing countries has been debated extensively. The main purpose of these debates was to formulate a hypothesis about the sustained effect of FDI on the development of the host country. Most of this literature lends support to the hypothesis that FDI led to the development of developing countries. This section concentrates on the sustained effect of FDI on the development of host developing countries. Selected studies are organized as follows:

Ridzuan, A. R., Ismail, N. A., and Hamat, A. F. C. (2018), using both annual data from 1970 to 2013 and an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) estimation technique, explored whether FDI and trade lead to sustainable development in Malaysia [51]. The results show that FDI inflows have successfully boosted growth rates, improved income distribution, and reduced pollution levels as the central pillar of sustainable development. The authors argue that Malaysia achieved this by introducing various relevant policies aimed at achieving the sustainable development pillars and formulating a comprehensive plan.

Fang, Y. (2021), based on mixed data in 2018 and 2019 and the ordered probit model, explored the influence of China’s FDI on the trend of achieving SDG scores in Africa [52]. He found that China’s FDI helps African countries achieve some SDGs in the economic and environmental dimensions, but China’s FDI in Africa does not have any significant effect on the progress of achieving social dimension SDGs.

Şentürk and Kuyun (2021) used time-series data from 1990 to 2018 and co-integration and VECM-based causal analysis to assess the relationship between FDI and sustainable development [53]. That is, they examined whether a relationship between the two variables existed, and they found that both variables interacted over time. Furthermore, they found a one-way relationship between FDI and per capita gross domestic product, as well as per capita energy consumption, and a two-way relationship between per capita gross domestic product and per capita energy consumption. Their results support the idea that, in terms of sustainable development, an increase in FDI has significant direct economic effects, including increased income to the host country, higher employment, and a higher growth rate. The study suggests that the development of Turkish legislation to attract more FDI and measures to ensure macroeconomic stability will have a positive impact on Turkey’s sustainable development.

A study by Awolusi and Adeyeye [54] found that South Africa’s output growth was more favorably affected by FDI than that of Nigeria, Egypt, Kenya, and the Central African Republic. Alege and Ogundipe [55] employed the system-GMM technique to examine the link between FDI and economic growth from 1970 to 2010 in ECOWAS member countries. Their findings do not support earlier research as the shares of FDI in output growth were found either insignificant or negative, irrespective of the control variables. Based on these findings, the authors suggest that ECOWAS policymakers should be cautious in embracing earlier studies’ recommendations in ECOWAS, most of which recommend excessive openness. These findings highly corroborate the arguments of dependency theorists.

Similarly, Fauzel, Seetanah, and Sannassee [56] investigated the complex linkage between FDI and poverty reduction in Mauritius from 1980 to 2013 within a VECM framework. The regression results show that FDI has contributed towards boosting social welfare in this country or towards reducing poverty. In a similar vein, Aust, Morais, and Pinto [57] used both multivariate analysis and an ordered probit model to study whether FDI plays a meaningful role in achieving the end goals of SDGs in 44 African countries and found that it does. However, beyond its positive impact on basic needs such as infrastructure and clean water, unfavorable environmental risks are unavoidable in host developing countries, thereby supporting one of the main tenets of dependency theory. Likewise, Bokpin [58] investigated the effect of incoming FDI on the ecosystem in Africa, and his findings revealed that an increase in incoming FDI flows significantly perpetuates the environmental crisis in this continent. This also corroborates the core tenets of the dependency theory.

Ojewumi and Akinlo [25] used both panel vector autoregressive (PVAR) and panel vector error correction (PVEC) techniques to study how incoming FDI, economic growth, and environmental quality interact in Sub-Sahara African (SSA) countries. The outcomes of this study support the hypothesis of an interaction between these series at a rate that ranges between 12.1 and 32.8 per cent, thereby confirming one of the tenets of dependency theory. The study suggests that investment-friendly policies should be balanced with environmental policies so that non-pollutants FDI, in other words, those that can improve the quality of the environment, are the only ones that should be welcomed in this region.

Similarly, Dhrifi, Jaziri, and Alnahdi [59] used a simultaneous model to analyze the direction of causality between FDI, carbon dioxide emission (CO2), and poverty for a panel of 98 underdeveloped economies from Asia, Africa, and Latin America (1995–2017). The overall findings suggest that FDI, poverty, and CO2 Granger are inter-related. Findings also reveal a significant negative link between FDI and poverty reduction for all group panels except the one for Africa. Furthermore, findings show the deleterious effect of FDI on CO2 for Africa, an inverted U-shape relationship for Asian countries, and finally, a positive impact of FDI on environmental quality in Latin America. These findings confirm the main key tenets of the dependency theory, especially for Africa, which states that developed countries can never lift developing countries out of poverty.

Another study on interactions by Coulibaly, Gakpa, and Soumaré [60] showed that the quality of property rights is a precursor to spill-over effects from incoming capital flows to output growth in resource-poor economies compared to resource-rich economies. Incoming capital flows were found to have had a more significantly steady-state spill-over effect on growth in emerging African nations than in their developing peers. Balsvik and Haller [61] employed the Norwegian manufacturing census and studied whether or not it is the modes of entry of FDI that matter in the productivity of host countries. They found that Greenfield, in general, exerts a detrimental effect on the productivity of local firms, while M&As exhibit a positive effect on the productivity of local firms in the same industry. Finally, Kalai and Zghidi [62] used ARDL and VECM techniques to undertake a similar study in 15 Middle Eastern and North African countries (1999–2012). Their findings favored long-term unidirectional relationships running from FDI to growth in the study area. The findings also revealed that FDI is likely to generate positive externalities for the studied countries.

Evidence from the empirical literature improves our understanding of the partial effect of FDI on the development of host developing countries. While the demand for FDI by developing countries targets their development, past empirical literature on this is grey. That is, it is unclear from the theoretical and empirical review above whether FDI contributes sustainably to the development of host developing countries. This article addresses this gap by attempting to extend understanding from the partial effect to the sustained effect of FDI in the host African countries. In order to fill the empirical and theoretical gaps identified in the literature, we propose a multidimensional model for evaluating the sustainable effect of FDI on the development of host developing countries. That is, both frameworks of endogenous growth models and dependency theory encompass the overall character of FDI as a double-edged sword in developing countries and Africa, which will be combined in the same framework. In other words, endogenous models, or the independency theory, each on its own, will hardly hold water regarding the long-term contributory effects of FDI in developing countries. Based on the true character of FDI as a double-edged sword, the hypothesis of this study is formulated as follows: The overall sustainable effect of FDI on the development of host African countries is not inherently more important. If the results reject this hypothesis, it means that the sustained effect of FDI on the development of host African countries is inherently more important, and thus, these countries should put FDI at the heart of their development plans.

2.3. Towards a Conceptual Framework

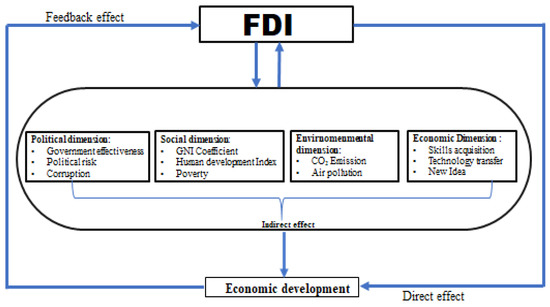

Figure 1 below shows how incoming FDI flows influence multifaceted dimensions of development in developing economies in the long-term. The nature of this influence ramifies into three main types of influences, namely: (1) direct (economic) influence (capital widening); (2) indirect economic influence; (3) indirect non-economic influence. Firstly, the direct economic influence of FDI, as shown by a downward arrow flowing from FDI to real GDP per capita, indicates that FDI directly affects investment in tangible assets of the host country, which is basically the key ingredient to GDP per capita.

Figure 1.

A proposed theoretical framework of how FDI influences the multifaceted dimensions of the development of host developing countries in the long run.

However, such investment is subjected to diminishing returns to capital and, thus, is incapable of explaining the growth of output in the long run. Neoclassical theory, commonly known as the Solow and Swan model, lays the foundation for the narrative summarized above.

The indirect economic influence of FDI encompasses the main channels through which FDI can generate long-term beneficial effects in host developing economies, and they are grouped into three major channels, namely: (1) technological transfer; (2) skills acquisition; (3) new ideas. These, in turn, ignite structural change in the economy. Endogenous growth models underpin this narrative, which assumes a constant return to capital as opposed to the Solow and Swan model. The analysis of the effect of FDI based on either the neoclassical economic model or endogenous models generates only a partial welfare effect of FDI in host developing countries since FDI is not without welfare-decreasing effects (costs) such as the exacerbation of income inequality and environmental degradation in host developing countries.

The welfare-decreasing effect of FDI on the other dimensions of development of host countries is analyzed within the framework of the dependency theory and is captured, for this case, by the arrow moving from social, environmental, and political dimensions, all of which pertain to the development of the country in question with regard to real GDP per capita as shown in Figure 1. Thus, the sustainable effect of FDI on development in host developing countries cannot be captured in a single theory. As alluded to previously, each theory highlighted here on its own hardly holds water with regard to the sustainable effect of FDI on host developing countries as it hinges on the balance between welfare-increasing and decreasing effects on host developing countries. In the current analysis, both welfare-increasing and decreasing effects of FDI are equally important. It may be true that FDI generates positive effects, but one needs to be wary of the overstatement of this effect at the expense of negative ones. Thus, we hypothesize that the long-term contributory effect of FDI on the development of host African countries would be minuscule. This is because while the welfare-increasing effect of FDI, as hypothesized by the neoclassical and endogenous growth models, excludes its costs, the overall welfare effect depends on the balance between increasing and decreasing effects.

3. Materials and Methods

The theoretical framework that links FDI to the host country’s long-term development can suitably be investigated using endogenous technology [63], as shown below. Endogenous models attempt to relax the assumptions of the neoclassical growth model to allow growth to continue even in the long run. Under this theory, the economy generates the overall output according to the following production technology:

where is the level of income, stands for time, denotes broad measures of capital, which include, for our case, inward FDI, private gross domestic fixed capital formation public gross fixed capital formation (PGFCF), and human capital (H), can be defined as an enhancement in technology that upsurges the efficiency of the labor force, while and are the elasticities. The Equation can be rewritten as follows:

To avoid omitted variable bias, this study controls for social, environmental, and political variables which directly or indirectly pertain to income . By incorporating these control variables into the model the following analytical framework is obtained:

where represents the vector of group-specific control variables grouped in three dimensions, namely, social variables , political variables and environmental variables, as highlighted earlier. However, analysis is limited to income inequality as a proxy for social variables, fossil carbon dioxide (CO2) as a proxy for environmental variables, and government effectiveness as a proxy for political variables. The selection of these variables was not only guided by the fact that they were the most employed in the past empirical literature but also, they were consistently and statistically significant. By rewriting Equation (2) into a dynamic panel model framework and introducing other independent variables identified in the literature, Equation (2) became:

where countries under analysis, years, represents real GDP per capita, stands for foreign direct investment as a percentage of GFCF, denotes total government expenditure on education, stands for private gross domestic fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP, stands for government investment minus investment on education as a share of GDP, stands for fossil carbon dioxide, stands for trade openness, stands for GDP deflator, stands for government effectiveness, stands for income inequality, denotes normal error term, and stands for country-specific intercept.

The dataset employed in this study refers to the annual panel data of thirty-five (35) selected African countries (Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Benin, Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Togo, Burundi, Cameroon, Central Africa, Congo Rep, Gabon, Comoros, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, and Zambia) and covers the period from 1990 to 2020. To avoid sample selection bias, all African countries were included except Djibouti, Eritrea, Liberia, Sao Tome and Principe, Somalia, Angola, Libya, South Sudan, and Sudan. This is because most of their data are unavailable. In addition, countries with insufficient and/or missing large data observations, such as Gambia, Mauritania, Chad, Ethiopia, Algeria, Gambia, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Seychelles, and Equatorial Guinea, were excluded from the current study. Table 1 below, provides the descriptions, expected signs and sources of variables. ( were acquired from the UNCTAD database (2020). Private gross domestic fixed capital formation () and public gross fixed capital formation were obtained from the IMF database, real GDP per capita , trade openness and income inequality ( were sourced from the World Development Indicators (WDI) 2020 online database published by the World Bank, Government expenditure on education were obtained from the UNESCO database, fossil carbon dioxide were sourced from the European Union Report (EUR) 2020 published by European Union, available at http://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 16 April 2021), and government effectiveness was sourced from World Governance Indicators (WGI).

Table 1.

Definition of variables and expected signs.

All these variables (Table 1) are expressed in percentages. Their choice was guided by theory, some previous empirical studies, and the availability of data for the sampled period.

This study focuses on panel data because it was only interested in the group and not in the individual unit in the group.

The coefficients of model () were estimated using the dynamic panel autoregressive distributed lag (P-ARDL) approach elaborated by Pesaran, Shin, and Smith [64]. This approach is based on two alternative estimators, namely, the mean group (MG) and the pooled mean group (PMG) estimators. In the first place, the PMG estimator assumes (i) long-run homogeneity of the coefficients across countries, or at least a subset of them, (ii) speed adjustment, short-run coefficients, error variances, and intercepts are heterogeneous country by country, (iii) residuals are assumed to be independently distributed across i and t, with zero mean and variances, and independently of the repressors, and finally, (iv) existence of the long run between series of interest.

On the other hand, the MG estimator mainly assumes that parameters are freely independent across the group. Both estimators equally assume that the series under consideration must be either I(0), I(1), or mutually co-integrated. More significantly, the size of T should be relatively large. This approach was employed at the expense of other co-integration test techniques, such as fixed and random effects estimators and generalized method of moments (GMM) estimators, as it allows for heterogeneity in the speed adjustment of the variable of interest towards the steady state equilibrium. As in the study by Pesaran, Shin, and Smith [64], a maximum lag value of one (1) was selected using the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). By considering one as the maximum lag length value, the dynamic panel ARDL (1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1) specification from Equation (3) was first formulated as follows:

where: , .

Secondly, following Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (1997), the error correction model corresponding to equation iv can be written as follows:

where: , , , and .

In model (5) is the group-specific speed of adjustment coefficient, represents the long coefficient, and ρ is the short-run coefficient. Model (5) can be estimated using PMG and MG estimators. However, the Hausman test was required to decide between the two estimators. The key requirements of this technique for efficiency, consistency, and reliability are, firstly, the existence of long-term relationships between study variables; the relative size of T is also of paramount importance, i.e., a large value of T allows the researcher to avoid bias in the mean estimate and study dynamic panel methods that help overcome heterogeneity [64,65].

The estimation of model (5) comprised the following seven steps: (i) testing for multicollinearity, (ii) testing for cross-sectional dependency, (iii) performing the first and second-generation panel unit-roots of the variables of interest, (iv) performing panel co-integration using the Kao panel co-integration test, (v) selecting the appropriate lag length for the individual variable by the use of the Akaike Information Criterion, (vi) performing the Hausman test to decide between the PMG and MG model, and (vii) estimating the parameters of the selected model (5), which finally leads to the interpretation and discussions of the results.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary statistics

Descriptive statistics provide the basic features of data under consideration. Table 2 below presents the summary statistics of the series employed in this study. The results from this table show that most of the variables (, , , , and ) exhibit a normal distribution as their skewness coefficients are lower than 3. Non-normally distributed series, such as PI and PGDFCF, were expressed as a percentage. As a result, the coefficients are interpreted as elasticity.

Table 2.

Summary statistics.

The results from Table 3 below conclude that the null hypothesis of no correlation among most pairs of the series is strongly rejected. Furthermore, reasonable correlation coefficients are in evidence as they are below the threshold values (0.5) of multicollinearity. Surprisingly, government effectiveness is highly and significantly correlated with environment degradation at 50 per cent. This implies that government policies are, by all means, growth-oriented, which raises some concerns for sustainable development. Therefore, there is a need for governments to consider tightening lax environmental regulations, which seem to have encouraged many environmental degradation-related activities.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix.

Cross-sectional dependence tests were performed on each panel and the residual of the model using the test elaborated by Pesaran [66]. Evidence from Table 4 below suggests that the series under consideration were cross-sectionally dependent. As a result, second-generation panel unit root tests were required.

Table 4.

Cross-sectional dependence test results.

4.2. Unit Root Analysis

To estimate the sustainable effect of FDI on real GDP per capita, careful checks were conducted on the individual properties of each panel of interest to ascertain that none of them is integrated with an order that is greater than 1 (I(1)). Having an unbalanced panel dataset, Im, Pesaran, and Shin [2] and PP-Fisher panel unit roots tests were carried out, and the outcomes are reported in Table 5 below. The evidence from this table rejects the hypothesis of a unit root for seven series, namely and , exclusively at their levels with constant and trend. The analysis did not show any evidence against unit roots for the remaining variables (, , and ). However, after the first difference, the latter became stationary (Table 5, under variables at first difference). Thus, all variables were found to be either I(0) or I(1).

Table 5.

Unit root test results.

Given that this study employed an unbalanced dataset, the current study took advantage of IM, Pesaran, and Shin [2] and PP-Fisher panel unit roots tests.

Furthermore, given the fact that the individual processes were found to be cross-sectionally dependent, a second generation of panel unit root tests based on Pesaran’s CADF was carried out to take care of cross-sectional dependency. The evidence from Table 6 below indicates that all series follow the I(1) order. The mixed outcomes of the dynamic panel unit roots (Table 5 above) suggest that the use of the P-ARDL approach in this study becomes a viable option.

Table 6.

Pesaran’s cross-sectional augmented Dicky–Fuller (CADF) test results.

As previously highlighted, we performed the Hausman test to decide between the MG and PMG models. The findings from Table 7 below indicate that PMG is more efficient as (Prob > chi2 = 0.9935) > 0.5. Thus, PMG was used to estimate the models of interest.

Table 7.

Hausman test results.

4.3. Co-Integration Analysis

Given the fact that study variables were found to be integrated with an order that is less than 2, we used the panel data co-integration test, elaborated by Kao [67], to examine the long-run relationship among the series under consideration. This test was employed at the expense of the Pedroni co-integration test because the number of series in the regression model exceeded eight, which made it inappropriate. The results reveal that co-integration exists among the series of interest as the p-value (0.000) < 0.01 (Table A1, in Appendix A).

4.4. Empirical Evidence on the Sustainable Effect

Table 8 below shows the overall estimation coefficients of Equation (4) and reveals the sustainable effects of the repressors on real GDP per capita for the sampled countries. The estimated coefficients are consistent with theoretical literature predictions. More importantly, all our control variables exerted considerable influence on the dependent variable.

Table 8.

Estimated coefficients of the long-run effects on real GDP per capita.

Firstly, the overall long-term estimated effect of FDI on real GDP per capita (= 0.06) is positive and strongly significant at the 10 percent level. This implies that, in the long run, FDI exerts an influence on real GDP per capita in the studied geographical area. This finding is consistent with endogenous growth models, which maintain that foreign capital flaws contribute favorably to the sustainable development of host countries through its various forms of externalities. The externalities account for non-diminishing returns to capital. The share of FDI on real GDP per capita (0.06) is, however, economically minuscule. This finding is in line with that of Aitken and Harrison [68] and Tvaronavičienė and Lankauskienė [10], who posit that the share of FDI on development tends to be relatively minuscule in countries with low income. Furthermore, this finding also supports the argument that FDI is less beneficial to developing countries because of their inability to absorb it. According to Adegboye et al. (2021), Africa saw an increase in FDI without significant welfare improvements [69]. The high elasticity of FDI estimated in previous studies may be due to the overestimation of the FDI effect, limiting its impact to one aspect or sub-aspects of sustainable development [70].

As hypothesized, government expenditure at all levels of education (GOVEDUC) contributes positively and significantly, at a 5 percent level, to real GDP per capita, for the entire sample by more than 16 percent (Table 8). Overall, this suggests that expenditure on education has a substantial effect on the long-term development of African countries. Accordingly, African countries should consider more expenditure on knowledge-intensive development to compete in the global market economy, which is knowledge driven. This conclusion lends support to previous empirical findings by Yusuf and Nabeshima [71], who argued that knowledge acquisition is essential for today’s modern economy as it knows no boundaries. Interestingly, the estimated result shows that it is not only government expenditure on education that contributes favorably to real GDP per capita but also other expenditures on other investments by the governments.

The overall trade openness coefficient is positively related to real GDP per capita, as hypothesized, but not statistically significant (Table 8). This implies that, on the whole, trade liberalization has no effect on real GDP per capita in the study area. Thus, the claim that opening up to trade makes every party involved better off is problematic in African economies. This is in line with the view that internal reforms towards the outside world by immature and small economies, including African countries, benefit their large economies’ trading partners through what is commonly known as a “dominance relationship or unequal exchange”. Thus, this calls for a more balanced relationship. Similarly, private gross domestic fixed capital formation has exerted no lasting contributory effect on real GDP per capita in the study area. This finding corroborates that of Rafindadi and Yosuf [72], who argue that the private sector in Africa contributes insignificantly to economic progress. A possible explanation advanced by the authors is that the private sector in Africa is still immature.

As can be observed in Table 8, the most substantial variable influencing the overall real GDP per capita in African countries is environmental degradation. Its coefficient is as high as negative (−) 0.51 and is strongly significant at the 10 percent level. This may imply the exploitation of natural resources [10], which has a seriously detrimental effect not only on real GDP per capita in the long run but also on the health of the poor [73]. According to these authors, health issues create difficulties for poor people to work and earn income, thus widening income inequality between the rich and the poor. As a result, sustainable development cannot be materialized if mechanisms are not put in place to safeguard the environment against excessive degradation in the study area. However, environmental degradation in resource-scarce economies seems to be peripheral compared to the pressing issues of poverty reduction and economic growth. It is fair to conclude that any attempt to bring about poverty reduction and economic growth may be offset by the consequences of environmental degradation. Thus, encouraging development and adaptive capacity in equal measure is the best way to go. Otherwise, promoting one at the expense of the other is a road that leads to nowhere, or it is like fighting a lost battle.

The above suggests that emphasis must be placed on environment protection as a prerequisite to wellbeing in Africa. To that end, policy makers in the considered countries should ensure that the adverse effect of economic activities is entirely contained within a sound regulatory framework. Another noticeable result emerging from the data is that income inequality, overall, exerts a negative and significant influence on real GDP per capita by more than 2 percent in the long run (Table 8). Our results show that government efforts to reduce income inequality will increase real GDP per capita in the study area.

Similarly, in the long run, inflation exerts a meaningful adverse effect on real GDP per capita in the study area (Table 8). The long-term effect of inflation may be dangerous to any economy as it would discourage current and aspiring investors from expanding their economic activities. Therefore, there is a need to fight inflation and income inequality to improve the wellbeing of Africans. Lastly, the government’s effectiveness has marginally influenced real GDP per capita in the geographical areas studied. Table 8 also shows that the overall speed of adjustment () is negative, (−) 0.84, and is statistically highly significant at 10 percent. The value of 0.84, in its absolute term, suggests that approximately 84 percent of the chill wind of the deviances from the steady state equilibrium in the previous year is corrected at the moment. As a result, the pace of adjustment is rapid. Consequently, the overall long-term association is steady.

The estimates for each studied country were regressed and reported in Table 9 below. Both error correction term coefficients () and short-term parameter estimates for each country are reported in this table. The estimated coefficient () for each country is negative and statistically significant. This implies that there is statistically significant evidence of steady-state equilibrium for countries under investigation. This finding corroborates that of Coulibaly, Gakpa, and Soumaré [60], who found a significantly negative speed of adjustment in their study carried out in Africa. Results of the coefficients of range from negative 0.005 to 1.559 (Table 9).

Table 9.

Country-specific estimations of FDI effect on real GDP per capita.

The fastest speed adjustment was observed in Morocco where = 1.559, Malawi where = −1.391, Mali where = −1.384, and Mauritius where = −1.357, while the lowest ones were recorded in South Africa with = 0.005 and Cape Verde where = −0.316. Obviously, the hypothesis of no long-term relationship among the study variables would be rejected across countries. Additionally, the findings show that FDI positively and significantly affects the aggregate demand of countries such as Cape Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Burundi, Kenya, Madagascar, Rwanda, Uganda, Mozambique, and Zambia in the short term. Similarly, the findings show that FDI affects, positively but not significantly, countries such as the Central Africa Republic and Comoros in the short run. FDI negatively and significantly affects countries such as Morocco, Egypt, Benin, and Ghana in the short run (Table 9, column 3). These findings corroborate those of ref. [74], who found that FDI helps stimulate economic growth in the long run, although it had an adverse effect in the short run for the countries under investigation [74]. This study was also concerned with whether it is the quantity of FDI that matters primarily in host country studies.

To achieve this, the analysis of data was first undertaken at the country level for the first five most beneficiaries and last five least beneficiaries of FDI where Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Congo. Rep, Zambia, and Namibia ranked higher as the most beneficiaries of FDI, while Burundi, Comoros, Algeria, Gabon, Burkina Faso, and Cameroon were the least beneficiaries of FDI in net incoming annual average FDI as a percentage of GDP in the sample. The study then proceeded to indicate whether a high share of FDI in income matters economically or not, regarding the magnitude of the effect on real GDP per capita. The evidence from country-specific estimations is inconclusive because none of the countries with a high share of FDI in income had the highest speed of adjustment. Additionally, their short-run effects of FDI on real GDP per capita were no better than those with a small share of FDI in income and vice versa.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

The main objective of this paper was to empirically examine the ability of FDI to sustainably affect the development of host African countries. To this end, a panel of data from 35 African countries for the period from 1990 to 2020 was used. This study leveraged the PMG/ARDL panel approach recently developed by Pesaran et al. [64] to estimate the sustainable impact of FDI on the development of African countries.

The empirical analysis of this study yielded several results. The overall estimated sustainable impact of FDI on real GDP per capita = 0.06) is statistically positive and significant at the 10 percent level for the entire sample, but its size is very small economically. Based on this result, our hypothesis that “the overall sustainable effect of FDI on the host African countries’ development, if any, is economically too small” was verified and confirmed. This indicates that unless new measures are taken to strengthen the FDI scale effect, investment promotion agencies (IPAs) that serve both the interests and concerns of foreign investors in Africa will not deliver much-needed development on the continent. Interestingly, public expenditure on education at all levels (GOVEDUC) is a positive and significant contributor to real GDP per capita. In other words, a 1% increase in public spending on all levels of education increases GDP per capita by approximately 16%, leaving the rest constant. This suggests that FDI is not at all inherently more important than alternative investment forms, especially domestic investment. African countries are therefore encouraged to pay more attention to national development in their efforts to combat underdevelopment. In line with this, it is necessary for African countries to develop their domestic financial sector and then use it to finance development projects and to be less dependent on external financing [75]

The most striking result emerging from the data is that environmental degradation (CO2) is the dominant variable that negatively affects () the real GDP per capita over the long term in African countries. This act is an obstacle to sustainable development in Africa. Another salient result emerging from the data is that overall, income inequality (GINI) has a significant and negative effect, while the government’s effectiveness (GOV) has a beneficial but insignificant impact on real GDP per capita in the long run. Thus, CO2, GINI, and GOV play an important role in the relationship between FDI and sustainable development. Particularly, the results clearly show that social and environmental issues are key challenges hindering Africa’s overall progress towards sustainable development. To ensure sustainable development in Africa, environmental degradation and income inequality must decrease or at least remain constant over time. Deterioration in these key aspects of sustainable development moves countries away from sustainable development with serious consequences such as poverty, weather extremes, etc. [76], while gradual improvement brings them closer together. Addressing these pressing issues by promoting the principles and practices of “sustainable investing” could be a potential solution to setting the development trajectory of the countries under study.

The overall estimated coefficient of the speed of adjustment ( = −0.84) is negative and statistically significant. This implies a long-run equilibrium relationship between a series of interests. The estimate of the error correction term for each specific country is negative and statistically significant, implying there is statistically significant evidence of steady-state equilibrium for each of the sampled countries. The fastest speed of adjustment was recorded in Morocco, where = 1.559, while the lowest speed was recorded in South Africa, where = 0.005.

In terms of policy implications, first, governments of the countries included in the sample should continue to welcome foreign investors but with greater emphasis on sustainable investment through FDI pathways for sustainable development. Second, given the detrimental effects of environmental degradation in the area under investigation, it is important to balance the government’s growth-oriented policy with the need for environmental protection through the strengthening of soft environmental regulations that seem to have contributed greatly to environmental destruction. Third, public spending on education at all levels (GOVEDUC) has been found to be a major contributor to favorable development in African countries, so African governments should commit to increasing education spending to improve literacy, learning conditions, teacher quality, and overall quality. Fourth, income inequality negatively impacts real GDP per capita, and policymakers in these countries should consider reducing income inequality, for example, by increasing spending on public education and health to achieve sustainable development. These governments should also encourage foreign investors to invest in poor sectors such as education, agriculture, healthcare, and infrastructure in their quest to curb income inequality. Finally, as inflation has been found to have a significantly negative impact on real GDP per capita in the long run, African policymakers should make a concerted effort to reduce inflation by increasing real output through increased productivity in order to achieve sustainable development.

For future research, this study is limited to one variable as a proxy for each of the non-economic aspects of sustainable development (environmental, social, and political) to avoid multicollinearity problems. Future studies may therefore consider using the alternative variables proposed in the conceptual framework presented in this study, which may lead to different outcomes of FDI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.; Methodology, A.K.; Software, A.K.; Validation, Z.S.; Investigation, Z.S.; Writing–original draft, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not relevant to this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the World Bank, United National Conference on Trade and Development, International Monetary Fund, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, World Governance Indicators, as well as the European Union.

Acknowledgments

We benefited greatly from the comments and suggestions received from Issouf SOUMARÉ, Serge A. Kablan, Rwamihigo Sylvestre. We are very grateful to Richard M. Benda for diligently proofreading this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Kao residual co-integration test results.

Table A1.

Kao residual co-integration test results.

| Series: Y1 FDIE GOVEEDUCE PGDFCF INFR INFLE CO3 TOE GOVE GINIE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Statistic | Prob. | |||

| ADF | −5.288034 | 0.0000 | ||

| Residual variance | 38.35344 | |||

| HAC variance | 7.893430 | |||

Appendix B

Table A2.

Variance inflation factors.

Table A2.

Variance inflation factors.

| Coefficient | Uncentered | |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Variance | VIF |

| FDI | 7.79 × 10−5 | 1.825695 |

| GOVEDUC | 0.002851 | 3.985337 |

| PGDFCF | 8.25 × 10−5 | 2.144293 |

| PI | 0.000243 | 1.787120 |

| CO2 | 0.006570 | 1.842282 |

| TO | 2.03 × 10−5 | 6.786538 |

| INFL | 7.33 × 10−5 | 1.353742 |

| GOV | 4.72 × 10−5 | 4.367378 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Study countries.

Table A3.

Study countries.

| Algeria | Ghana | Mauritius |

|---|---|---|

| Egypt | Guinea | Seychelles |

| Morocco | Senegal | Tanzania |

| Tunisia | Sierra Leone | Uganda |

| Benin | Togo | Rwanda |

| Guinea-Bissau | Burundi | Botswana |

| Cape Verde | Cameroon | Eswatini |

| Guinea | Central African Republic | Lesotho |

| Mali | Congo Rep. | Malawi |

| Niger | Gabon | Mozambique |

| Nigeria | Comoros | Namibia |

| Burkina Faso | Kenya | South Africa |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Madagascar | Zambia |

References

- Polloni-Silva, E.; Roiz, G.A.; Herick, F.M. The Environmental Cost of Attracting FDI: An Empirical Investigation in Brazil. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.S.; Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J. Econom. 2003, 115, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, K. ‘Sustainable Investing’ via the FDI route for sustainable development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 37, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudnovsky, D.; López, A. Globalization and Developing Countries: Foreign Direct Investment and Growth and Sustainable Human Development; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mainguy, C. L’impact des investissements directs étrangers sur les économies en développement. Région Dév. 2004, 20, 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dornean, A.; Chiriac, I.; Rusu, V.D. Linking FDI and Sustainable Environment in EU countries. Sustainability 2021, 14, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2014: Investing in the SDGs—An Action Plan; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1–246. ISBN 978-92-1-112873-4. [Google Scholar]

- WBG. Global Investment Competitiveness Report 2017/2018: Foreign Investor Perspectives and Policy Implications; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–185. ISBN 978-1-4648-1175-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.A. The Theory of Economic Growth; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 1–453. ISBN 9781135033507. [Google Scholar]

- Tvaronavičienė, M.; Lankauskienė, T. Plausible foreign direct investment’impact on sustainable development indicators of differently developed countries. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2011, 1, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K.P.; Zarsky, L. The Enclave Economy: Foreign Investment and sustainable Development in Mexico’s Silicon Valley; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; p. 0262262967. [Google Scholar]

- Zarsky, L. International Investment for Sustainable Development: Balancing Rights and Rewards; Earthscan: London, UK, 2005; p. 1844070387. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvant, K.P. The Challenge: How Can Foreign Direct Investment Fulfil Its Development Potential? OECD: Paris, France, 2016; pp. 50–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F.; Draz, M.U.; Su-Chang, Y. What drives OFDI? Comparative evidence from ASEAN and selected Asian economies. J. Chin. Econ. Foreign Trade Stud. 2018, 11, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megbowon, E.T.; Ngarava, S.; Mushunje, A. Foreign direct investment inflow, capital formation and employment in south Africa: A time series analysis. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Stud. 2016, 8, 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Hermes, N.; Lensink, R. Foreign direct investment, financial development and economic growth. J. Dev. Stud. 2003, 40, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, S.; Narula, R. Foreign Direct Investment and its Role in Economic Development: Do We Need a New Agenda? Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2004, 16, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, S.I. FDI and economic development in Africa. A Paper Presented at the ADB/AERC International; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Tunis, Tunisia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Geiger, M.; Fu, M. Manufacturing FDI in Sub-Saharan Africa; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Afesorgbor, S.K.; van Bergeijk, P.A.G.; Demena, B.A. COVID-19 and the Threat to Globalization: An Optimistic Note. In COVID-19 and International Development; Papyrakis, E., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 29–44. ISBN 978-3-030-82339-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyanwu, J.C.; Salami, A.O. The impact of COVID-19 on African economies: An introduction. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2021, 33, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgieva, K. IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva’s Statement Following a G20 Ministerial Call on the Coronavirus Emergency; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Y.; Kolstad, C.D. Do lax environmental regulations attract foreign investment? Environ. Resour. Econ. 2002, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassaballa, H. Testing for Granger causality between energy use and foreign direct investment inflows in developing countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojewumi, S.J.; Akinlo, A.E. Foreign direct investment, economic growth and environmental quality in sub-Saharan Africa: A dynamic model analysis. Afr. J. Econ. Rev. 2017, 5, 48–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lingjia, C. The Environmental Effect of FDI: A New Research based on the Panel Data of China’s 112 Key Cities. World Econ. Study 2008, 9, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Denisia, V. Foreign direct investment theories: An overview of the main FDI theories. Eur. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2010, 2, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jahanger, A.; Usman, M.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. Linking institutional quality to environmental sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 1749–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdum, M.S.A.; Usman, M.; Kousar, R.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Radulescu, M.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. How do institutional quality, natural resources, renewable energy, and financial development reduce ecological footprint without hindering economic growth trajectory? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C. Does foreign direct investment affect domestic income inequality? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2006, 13, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzer, D.; Hühne, P.; Nunnenkamp, P. FDI and Income Inequality—Evidence from L atin A merican Economies. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2014, 18, 778–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuveny, R.; Li, Q. Economic openness, democracy, and income inequality: An empirical analysis. Comp. Political Stud. 2003, 36, 575–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschi, E.; Vivarelli, M. Trade and income inequality in developing countries. World Dev. 2009, 37, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezuidenhout, H.; Kleynhans, E. Implications of foreign direct investment for national sovereignty: The Wal-Mart/Massmart merger as an illustration. S. Afr. J. Int. Aff. 2015, 22, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J. FDI and Sustainabledevelopment: Lessons to Draw for India. Annu. Res. J. SCMS 2014, 1, 56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Carbaugh, R.J. International Economics; Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2004; pp. 1–550. ISBN 9781439038949. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert, K.; Benmamoun, M.; Zhao, H. FDI inflow and human development: Analysis of FDI’s impact on host countries’ social welfare and infrastructure. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 55, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A.; Elliott, R.J.; Fredriksson, P.G. Endogenous pollution havens: Does FDI influence environmental regulations? Scand. J. Econ. 2006, 108, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Foreign Direct Investment for Development: Maximising Benefits, Minimising Costs; OECD: Paris, France, 2002; pp. 1–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciegis, R.; Ramanauskiene, J.; Startiene, G. Theoretical reasoning of the use of indicators and indices for sustainable development assessment. Eng. Econ. 2009, 63, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bissoon, O. Is Sub-Saharan Africa on a Genuinely Sustainable Development Path? Evidence Using Panel Data. Margin J. Appl. Econ. Res. 2017, 11, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wassal, K.A. Foreign direct investment and economic growth in Arab countries (1970–2008): An inquiry into determinants of growth benefits. J. Econ. Dev. 2012, 37, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.M. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, T.W. Economic growth and capital accumulation. Econ. Rec. 1956, 32, 334–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, R.E. On the mechanics of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 1988, 22, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, T. Foreign direct investment and economic development. Transnatl. Corp. 1992, 1, 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, P.M. Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, E.; Arnold, M.; Bendul, J.C. Business models for sustainable innovation–an empirical analysis of frugal products and services. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, S133–S145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimoli, M.; Dosi, G.; Stiglitz, J.E. The Political Economy of Capabilities Accumulation: The Past and Future of Policies for Industrial Development; LEM Working Paper Series: Pisa, Italy, 1 July 2008; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwu, A.C.; Ituma, O.S. Globalization and Underdevelopment in Africa. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2017, 25, 1776–1783. [Google Scholar]

- Ridzuan, A.R.; Ismail, N.A.; Hamat, A.F.C. Foreign direct investment and trade openness: Do they lead to sustainable development in Malaysia. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2018, 4, 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y. Influence of foreign direct investment from China on achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals in African countries. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 19, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şentürk, C.; Kuyun, Ş. An Analysis of the Relationship between Foreign Direct Investment and Sustainable Development. Ekon. Polit. Ve Finans Araştırmaları Derg. 2021, 6, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awolusi, O.D.; Adeyeye, O.P. Impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth in Africa. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2016, 14, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alege, P.O.; Ogundipe, A. Foreign direct investment and economic growth in ECOWAS: A system-GMM approach. Covenant J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzel, S.; Seetanah, B.; Sannassee, R.V. A dynamic investigation of foreign direct investment and poverty reduction in Mauritius. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2016, 6, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, V.; Morais, A.I.; Pinto, I. How does foreign direct investment contribute to Sustainable Development Goals? Evidence from African countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokpin, G.A. Foreign direct investment and environmental sustainability in Africa: The role of institutions and governance. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2017, 39, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhrifi, A.; Jaziri, R.; Alnahdi, S. Does foreign direct investment and environmental degradation matter for poverty? Evidence from developing countries. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2020, 52, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, S.S.; Gakpa, L.L.; Soumaré, I. The Role of Property Rights in the Relationship between Capital Flows and Economic Growth in SSA: Do Natural Resources Endowment and Country Income Level Matter? Afr. Dev. Rev. 2018, 30, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsvik, R.; Haller, S.A. Foreign firms and host-country productivity: Does the mode of entry matter? Oxf. Econ. Papers 2011, 63, 158–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalai, M.; Zghidi, N. Foreign direct investment, trade, and economic growth in MENA countries: Empirical analysis using ARDL bounds testing approach. J. Knowl. Econ. 2019, 10, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavacek, P.; Bal-Domanska, B. Impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth in central and eastern European countries. Eng. Econ. 2016, 27, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.P. Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999, 94, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Ning, J.; Yu, Z.; Xiong, H.; Shen, H.; Jin, H. Can environmental tax policy really help to reduce pollutant emissions? An empirical study of a panel ARDL model based on OECD countries and China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. General diagnostic tests for cross-sectional dependence in panels. Empir. Econ. J. Inst. Adv. Stud. Vienna Austria 2020, 60, 13–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. J. Econom. 1999, 90, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, B.J.; Harrison, A. Do domestic firms benefit from direct foreign investment? Evidence from Venezuela. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboye, F.B.; Osabohien, R.; Olokoyo, F.O.; Matthew, O.A. Foreign direct investment, globalisation challenges and economic development: An African sub-regional analysis. Int. J. Trade Glob. Mark. 2020, 13, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndikumana, L.; Verick, S. The linkages between FDI and domestic investment: Unravelling the developmental impact of foreign investment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Dev. Policy Rev. 2008, 26, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.; Nabeshima, K. Growth through Innovation: An Industrial Strategy for Shanghai; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 1–171. ISBN 9781861368. [Google Scholar]

- Rafindadi, A.A.; Yosuf, Z. An application of panel ARDL in analysing the dynamics of financial development and economic growth in 38 sub-Saharan African continents. In Proceedings of the Proceeding-Kuala Lumpur International Business, Economics and Law Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2–3 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Handayani, B.D.; Yanto, H.; Pujiati, A.; Ridzuan, A.R.; Keshminder, J.; Shaari, M.S. The Implication of Energy Consumption, Corruption, and Foreign Investment for Sustainability of Income Distribution in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.T.-H.; Vo, D.H.; The Vo, A.; Nguyen, T.C. Foreign direct investment and economic growth in the short run and long run: Empirical evidence from developing countries. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2019, 12, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achuo, E.D.; Nchofoung, T.N.; Asongu, S.; Dinga, G.D. Unravelling the Mysteries of Underdevelopment in Africa; AGDI Working Paper: Yaoundé, Cameroon, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi, S.; Garg, N.; Paudel, R. Environmental degradation: Causes and consequences. Eur. Res. 2014, 81, 1491. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).