Development and Effectiveness of Agricultural Cooperatives: Case of Maize Producer Cooperatives (MPCs) in the Republic of Benin

Abstract

1. Introduction

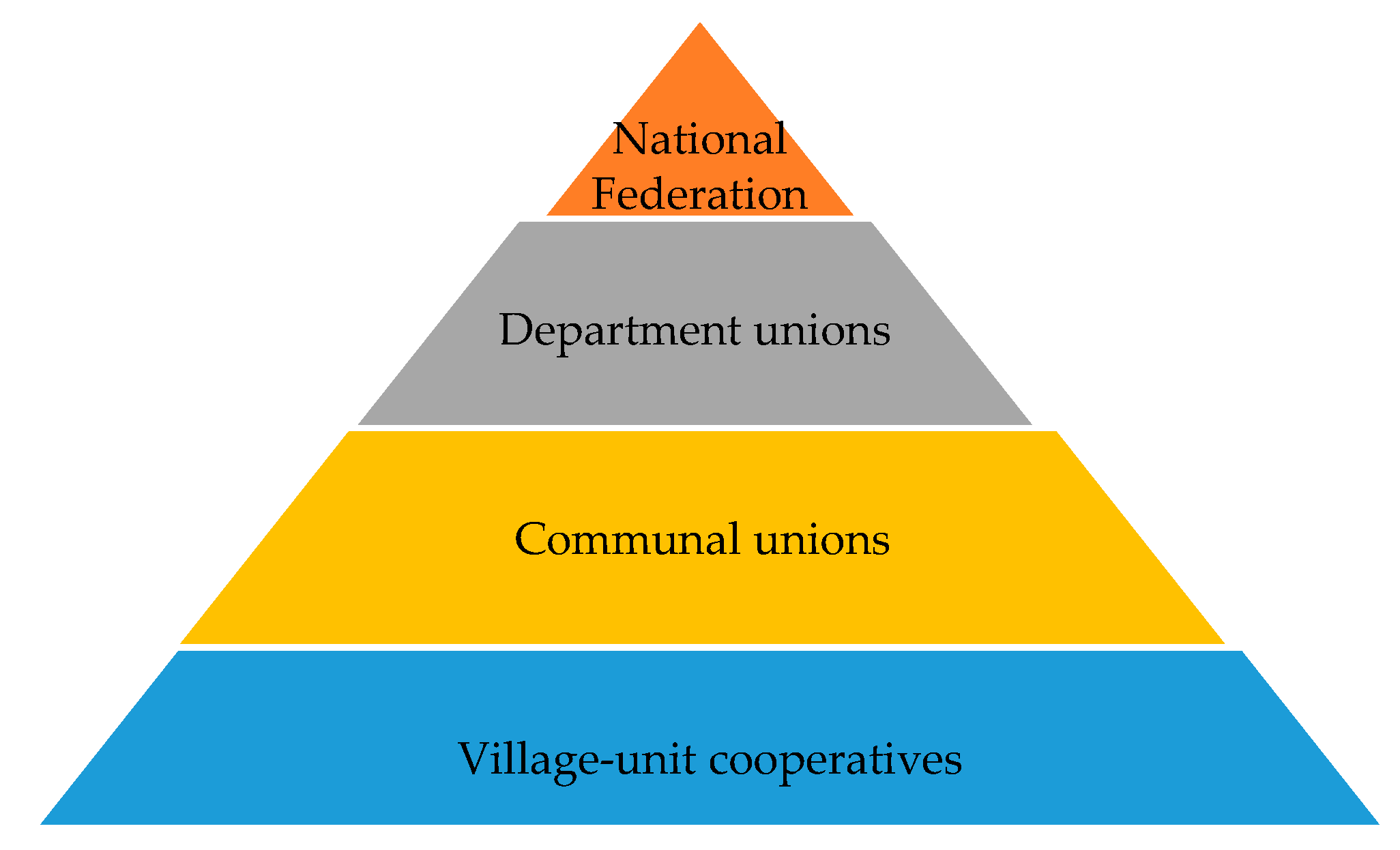

2. Background

2.1. Brief Overview of ACs

2.2. Assessment of ACs’ Effectiveness

3. Materials and Methods

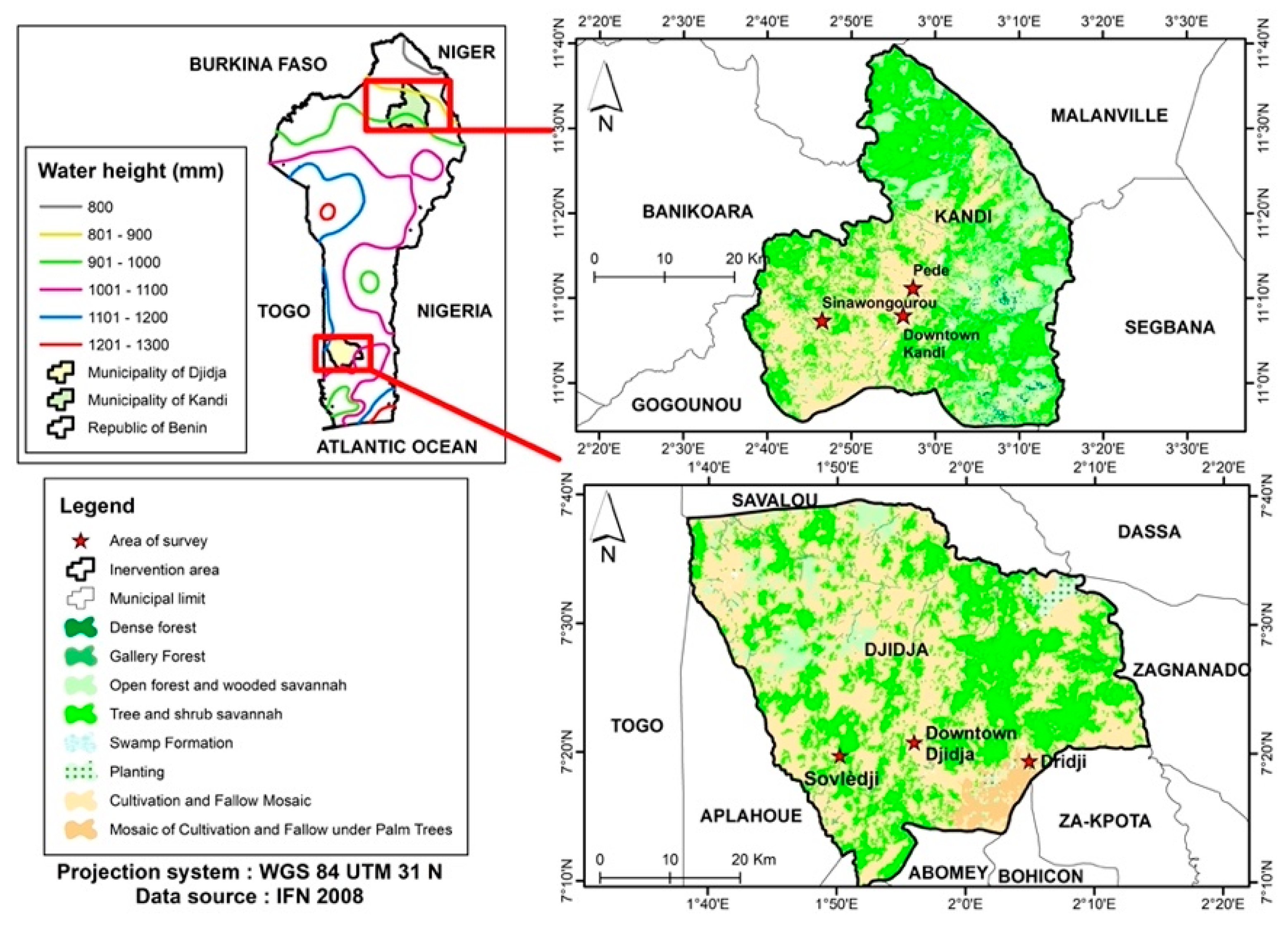

3.1. Study Areas

3.2. Research Methodology

4. Findings

4.1. Cases Description

- MPCs in Kandi

“First, the promise of increasing government support, mainly in acquiring inputs; second, the existence of partners willing to support them; and lastly, a guarantee of a market for maize products.”

“A large majority of members are disheartened by the discontinuation of support programs and the new registration process required by extension officers… This new registration process required them to pay another subscription fee and contribute to forming a new capital, which they deemed unfair and demotivating.”

“The secretary, due to his level of education, holds a crucial role in the cooperative’s affairs, particularly in support and aid coordination. However, this has caused resentment from the president, who feels that the secretary and his allies are disproportionately benefiting from the cooperative, thereby causing division and hindering the union’s progress.”

“The group was considering selling maize grain at 12000XOF per 100 kg but switched to a higher offer of 14000XOF per 100 kg. However, the higher offer fell through, and the maize was sold at a lower price of 8000XOF, leading to a loss. This negative outcome made some members question the cooperative’s joint selling efforts.”

- MPCs in Djidja

“Extension officers emphasized the importance of a legal framework for recognition, opportunities for securing markets through contracts, and working with more partners to increase maize production and marketing in Djidja.”

“Their primary role is making decisions related to maize production and marketing, representing cooperatives, keeping books, and help in looking for partners and donors…”

“The low ability in contract enforcement, inability to satisfy members’ demand for higher prices, and absence of market.”

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Cases

- Institutional Environment

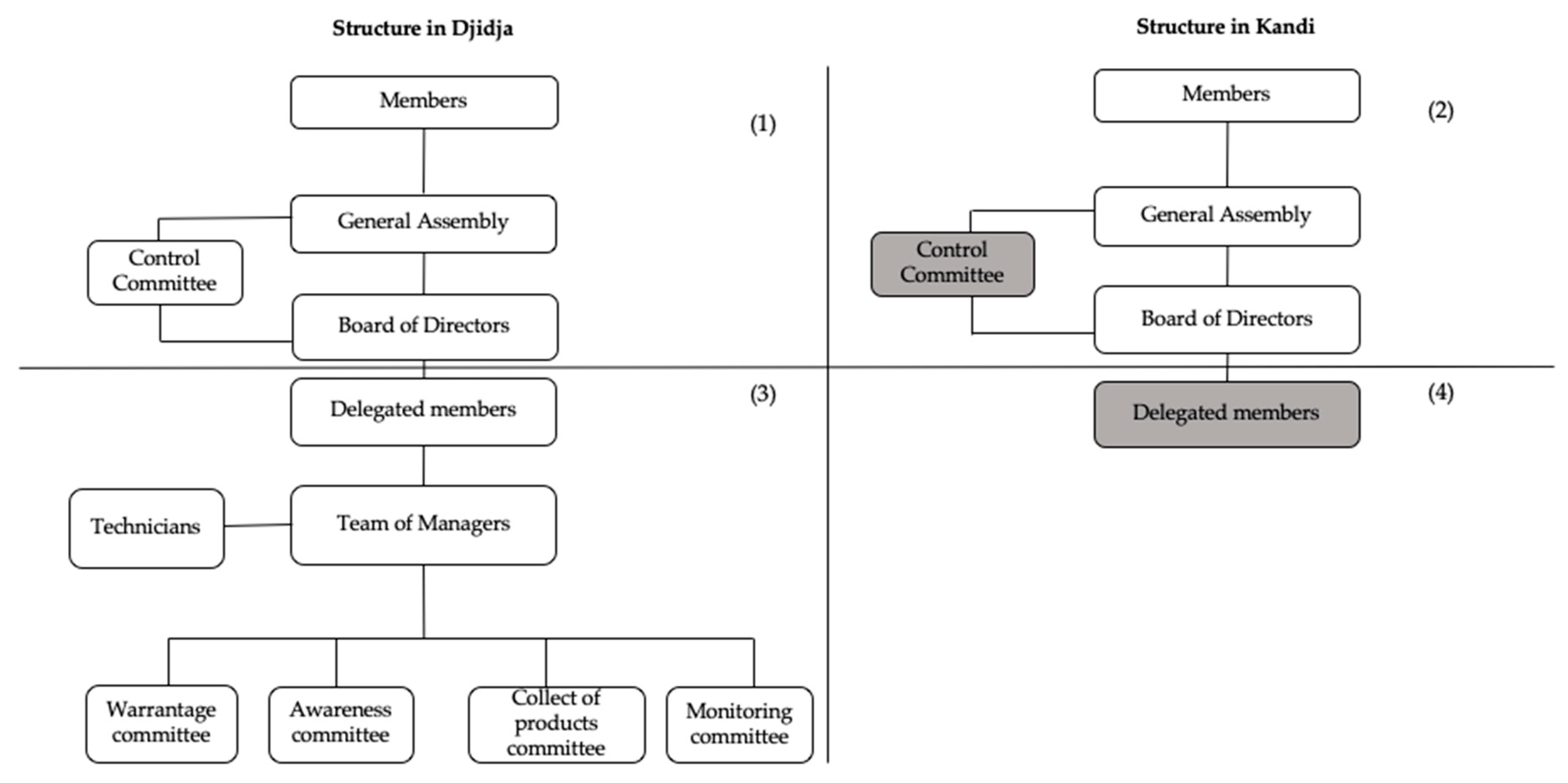

- Internal Governance

4.3. Discussions

5. Conclusions

- Members should be the starting point that motivates an AC establishment. MPCs should be established based on producers’ will and shared values instead of being reduced to a simple get-together of producers.

- The government must redefine its roles in establishing and developing cooperative societies. Training on agricultural cooperatives is of the utmost importance, and emphasis should be placed on the organizational design of their cooperation. It is essential that the state also regulates support systems, particularly cooperatives’ relations with partners, to avoid the possibility of leading them astray or in the wrong direction.

- Despite a build-up and experiment phase, knowledgeable or trained leaders are essential to rule cooperative bodies and stimulate members’ participation.

- Services to members, especially joint selling, is a business that deserves capacity building in cooperative management to guarantee that cooperatives fulfill the primary mission for which they were set up.

- Given some MPCs’ small size and the limited resources on which they operate, strengthening collective action through cooperation with other cooperative societies operating at the same level would constitute an opportunity to reach a meaningful scale.

- Conflicts between leaders or members, affecting the MPC’s performance sometimes to the point of turning them inoperative, deserve careful investigation to understand the causes and, above all, to strengthen the mechanisms for managing these conflicts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. Agricultural Competitiveness and Export Diversification Project; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Direction de la Statistique Agricole (DSA-Bénin). Recensement National de l’Agriculture 2019, Volume 3, Principaux Tableaux; Ministère de l’Agriculture de l’Elevage et de la Pêche: Cotonou, Benin, 2021.

- Wanyama, F.O.; Develtere, P.; Pollet, I. Reinventing the Wheel? African Cooperatives in a Liberalized Economic Environment. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2009, 80, 361–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchall, J.; Ketilson, L.H. Resilience of the Cooperative Business Model in Times of Crisis; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; ISBN 978-92-2-122409-9. [Google Scholar]

- Tefera, D.A.; Bijman, J.; Slingerland, M.A. Agricultural Co-Operatives in Ethiopia: Evolution, Functions and Impact: Agricultural Co-Operatives in Ethiopia. J. Int. Dev. 2017, 29, 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, A. (Ed.) Promoting Rural Cooperatives in Developing Countries: The Case of Sub-Saharan Africa; World Bank Discussion Papers; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-8213-1786-0. [Google Scholar]

- Manne, A.S.A.; Jimmy, P.; Edja, H.; Nouhoun, A.R.; Nasser Baco, M.; Moumouni, I. Analysis of the Evolution of the Regulatory and Operational Framework for the Management of Cooperatives in Benin. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2021, 10, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gning, T.; Larue, F. Le Nouveau Modèle Coopératif Dans l’espace OHADA: Un Outil Pour La Professionnalisation Des Organisations Paysannes? Etudes–Fondation pour l’Agriculture et la Ruralité dans le Monde: Monrouge, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ohada, Droit des Sociétés Cooperatives–Acte Uniform OHADA. 2010, p. 72. Available online: https://www.sgg.cg/txts-droit-reg/OHADA-Acte-uniforme-2010-societes-cooperatives.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Ibikoule, G.E.; Lee, J. Characteristics of Trends and Historical Path of Agricultural Cooperatives in the Republic of Benin. Bull. Fac. Agric. Kagoshima Univ. 2021, 71, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ibikoule, G.E.; Lee, J. Impact of Cooperatives on Farm Performances in The Republic of Benin: A Maize Producer Households Study in Alibori. Jpn. J. Food Agric. Resour. Econ. 2022, 73, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tewodros, B.A. Assessment of Factors Affecting Performance of Agricultural Cooperatives in Wheat Market: The Case of Gedeb Hasasa District, Ethiopia. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 11, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzuyanda, C. Assessing the Impact of Primary Agricultural Co-Operative Membership on Smallholder Farm Performance (Crops) in Mnquma Local Municipality of the Eastern Cape Province. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Fort Hare South Africa, Alice, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thaba, K.; Anim, F.D.K.; Tshikororo, M. Analysis of Factors Affecting Proper Functioning of Smallholder Agricultural Cooperatives in the Limpopo Province of South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 54, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, E.; Getachew, D. Factors Affecting Success of Agricultural Marketing Cooperatives in Becho Woreda, Oromia Regional State of Ethiopia. Int. J. Coop. Stud. 2015, 4, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shiferaw, T. Factors Affecting Coffee Marketing Cooperatives Performance in Ethiopia, Horn of Africa. 2022. Available online: ijmer.s3.amazonaws.com/pdf/volume11/volume11-issue1(5)/15.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Penrose-Buckley, C. Producer Organisations: A Guide to Developing Collective Rural Enterprises; Oxfam: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tossou, R.C. Le Groupement Villageois: Un Cadre de Participation Communautaire Au Développement Ou Un Instrument de Réalisation d’intérêts Individuels et Conflictuels. Bull. L’APAD, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Donaldson, J.A. Conference Paper No. 47 Why Farmers’ Cooperatives Failed in China? Re-Evaluating the Viability of Peasant Cooperatives in Agrarian. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference of the BRICS Initiative for Critical Agarian Studies, Moscow, Russia, 13–16 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berthomé, J.; Pesche, D. Version Provisoire; Ministère des Affaires Etrangères DGCID/DCT-EPS: Cotonou, Benin, 2003; pp. 1–36.

- Ménard, C. The Economics of Hybrid Organizations. J. Inst. Theor. Econ. 2004, 160, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J. Organisational Principles for Co-Operative Firms. Scand. J. Manag. 2001, 17, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollni, M.; Fischer, E. Member Deliveries in Collective Marketing Relationships: Evidence from Coffee Cooperatives in Costa Rica. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2015, 42, 287–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benos, T.; Kalogeras, N.; Verhees, F.J.H.M.; Sergaki, P.; Pennings, J.M.E. Cooperatives’ Organizational Restructuring, Strategic Attributes, and Performance: The Case of Agribusiness Cooperatives in Greece. Agribusiness 2016, 32, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounds, G.M.; Dobbins, G.H.; Fowler, O.S. Management: A Total Quality Perspective; South-Western Publishing Company: Nashville, TN, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Leković, B.; Marić, S. Measures of Small Business Success/Performance: Importance, Reliability and Usability. Industrija 2015, 43, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeras, N.; Pennings, J.M.E.; Benos, T.; Doumpos, M. Which Cooperative Ownership Model Performs Better? A Financial-Decision Aid Approach. Agribusiness 2013, 29, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noumen, R. Les Coopératives: Des Utopies Occidentales Du XIX e Aux Pratiques Africaines Du XX e. Rev. Française Gest. 2008, 34, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putterman, L. Extrinsic versus Intrinsic Problems of Agricultural Cooperation: Anti-incentivism in Tanzania and China. J. Dev. Stud. 1985, 21, 175–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérotin, V. Entry, Exit, and the Business Cycle: Are Cooperatives Different? J. Comp. Econ. 2006, 34, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSAE. Effectifs de la Population des Villages et Quartiers de Ville du Benin (RGPH-4, 2013); National Institute of Statistics and Economic Analysis: Cotonou, Benin, 2016; pp. 1–85. [Google Scholar]

- PDC Kandi. Plan de Développement Communal 2017–2021 Version Finale; Mairie de Kandi: Kandi, Benin, 2017; p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- ONASA. Département Du Zou/Colline. Rapport d’Evaluation de La Production Vivrière En 2008 et Des Perspectives Alimentaires Pour 2009 Au Bénin: Situation Par Département; CERPA/ZOU: Bohicon, Benin, 2008; Volume II, p. 187. [Google Scholar]

- Fossey, E.; Harvey, C.; Mcdermott, F.; Davidson, L. Understanding and Evaluating Qualitative Research. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2002, 36, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; (Applied Social Research Methods, Volume 5); SAGE Publication Ltd.: London, UK, 2003; pp. 359–386. [Google Scholar]

- Chaddad, F.R. Networking for Competitive Advantage: The Case of US Agricultural Cooperatives. In Proceedings of the The Annual World Symposium of the International Food and Agribusiness Management Association, Parma, Italia, 2 October 2006; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Morishima, T.; Kiyono, S. The Paths of Organizational Reform in European Agricultural Cooperatives: A Case Study of Agricultural Cooperatives in F&V Sector in Almeria, Spain. J. Rural Econ. 2019, 91, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Saarelainen, E.; Sievers, M. Combining Value Chain Development and Local Economic Development; ILO Value Chain Development; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Guédjé, L. Les politiques publiques de promotion des coopératives. In ÉPURE—Éditions et Presses Universitaires de Reims, Juin 202, Le Droit des Coopératives en Afrique: Réflexions Sur l’ Acte Uniforme de l’OHADA; Bibliothèque Robert de Sorbon: Ardennes, France, 2021; pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Houessou, D.M.; Sonneveld, B.G.J.S.; Aoudji, A.K.N.; Thoto, F.S.; Dossou, S.A.R.; Snelder, D.J.R.M.; Adegbidi, A.A.; De Cock Buning, T. How to Transition from Cooperations to Cooperatives: A Case Study of the Factors Impacting the Organization of Urban Gardeners in Benin. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAEP. Plan Stratégique de Développement du Secteur Agricole (PSDSA): Orientation Stratégiques; Ministère de l’Agriculture de l’Elevage et de la Pêche: Cotonou, Benin, 2017; p. 132.

- Manne, A.S.A.; Moumouni, I.; Nouatin, G.; Edja, H.; Vodouhe, S. Determinants of the Governance Performance of Producer Organizations: Case Study of Village Cotton Producers Cooperatives in Benin. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 38, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markelova, H.; Meinzen-Dick, R.; Hellin, J.; Dohrn, S. Collective Action for Smallholder Market Access. Food Policy 2009, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhoma, A.T. Factors Affecting Sustainability of Agricultural Cooperatives: Lessons from Malawi. Master’s Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Garnevska, E.; Liu, G.; Shadbolt, N.M. Factors for Successful Development of Farmer Cooperatives in Northwest China. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mubirigi, A.; Shukla, J.; Mbeche, R. Assessment of The Factors Influencing The Performance of Agricultural Cooperatives in Gatsibo District, Rwanda. Nternational J. Inf. Res. Rev. 2016, 3, 2755–2763. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Lu, H.; Wang, X. Social Capital, Member Participation, and Cooperative Performance: Evidence from China’s Zhejiang. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 49–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yanbykh, R.; Lerman, Z. Cooperative Tradition in Russia: A Revival of Agricultural Service Cooperatives? Post-Communist Econ. 2019, 31, 751–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovina, S.; Nilsson, J. The Russian Top-down Organised Co-Operatives—Reasons behind the Failure. Post-Communist Econ. 2011, 23, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Non-active.

Non-active.

Non-active.

Non-active.

| Characteristics | Kandi | Djidja |

|---|---|---|

| Location | North | Center |

| Total land (Km2) | 3421 | 2184 |

| Total population | 179,290 | 123,543 |

| Density | 52 | 57 |

| Agricultural households | 16,046 | 20,106 |

| Total maize production (T) | 50,639 | 31,704.75 |

| Yield of maize (T/ha) | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| Area of Survey | Kandi | Djidja | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location of coop | Kandi city | Pede | Sinawongourou | Djidja city | Sovlegnin | Dridji |

| Tier (level) | Union | Village | Village | Union | Village | Village |

| Current state | Non-active | Revived | Revived | Active | Active | Active |

| Date of creation | 2016 | 2016 | 2016 | 2017 | 2017 | 2017 |

| Number of members | N/A | 150 | 65 | 12,625 | 410 | 83 |

| Informants | Treasurer | Chairman 2 Members | Chairman 2 Members | Secretary Manager | Chairman 2 Members | Chairman 2 Members |

| Core Bodies | Number of Members | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Union | Pede | Sinawongourou | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| General Assembly | N/A | N/A | 135 | 15 | 57 | 8 |

| Board of Directors | N/A | N/A | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Supervisory board | N/A | N/A | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Core Bodies | Number of Members | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Union | Sovlegnin | Dridji | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| General Assembly | 12625 | 1768 | 410 | 69 | 83 | 15 |

| Board of Directors | 12 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Supervisory board | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Program | Duration | Type of Support | Details | Total Cost of Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACMA2 | 2018–2021 | Infrastructure | 1 warehouse of 500 T; 1 drying yard; and 1 toilet | 245,298 USD$ |

| Equipment | 100 palettes; 1 sewing machine; 1 moistener; 2 electronic scales; 1 generator; and others | |||

| Training | Access to market |

| Years | Communal Output (T) | Sold by Coop (T) | MPC’s Share (%) | Sold through Warrantage (T) | Unit (Bag) | Price/Bag (XOF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 25,053 | 1600 | 6.39 | 448 | 100 kg | 16,000 |

| 2019 | 26,177 | 2400 | 9.16 | 1200 | 100 kg | 15,500 |

| 2020 | 31,704 | 4800 | 15.14 | 1650 | 100 kg | 21,000 |

| Topics | Sub-Themes Emerging | Kandi | Djidja |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional environment | Legal framework | UA-COOP | UA-COOP |

| Initiator | Government | Government | |

| MPC’s Background | -Unstructured POs only in villages | -Structured POs at the village and district levels | |

| Rules and bylaw | -Involvement of extension officers in the design phase | -Independently designed by producers | |

| Administration | -Unstable | -Stable | |

| Registration | -Irregular | -Regular | |

| Support provided | -Initial support (equipment + infrastructure of poor quality) | -Continuous support (training + equipment + infrastructure of quality) |

| Topics | Sub-Themes Emerging | Kandi | Djidja |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal governance | Structure | -Well-defined (GA, BoD, and CC); Reliance on extension officers for technical decisions; Inactive bodies or inactive board members | -Well-defined (GA, BoD, and CC); Rely on a team of managers with professionals at district level; Active bodies and board members |

| Leaders’ profile and skills | -Largely non-educated; non trained leaders | -Largely non-educated; Trained in AC management | |

| Accountability and transparency | -No update of official records | -Update of official records | |

| Member’s participation | -Sporadic General Assemblies meetings; Weak participation of members | -Regular meetings; Participation promoted through comities; Active participation of Members | |

| Network | -Non-active union because of conflict between board members | -Active union | |

| -Limited shared resources and infrastructure | -Significant shared resources and infrastructure | ||

| Services | -Failure of joint selling | -Low ability in joint selling |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibikoule, G.E.; Lee, J.; Agalati, B.; Gillette, R. Development and Effectiveness of Agricultural Cooperatives: Case of Maize Producer Cooperatives (MPCs) in the Republic of Benin. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054480

Ibikoule GE, Lee J, Agalati B, Gillette R. Development and Effectiveness of Agricultural Cooperatives: Case of Maize Producer Cooperatives (MPCs) in the Republic of Benin. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054480

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbikoule, Godfrid Erasme, Jaehyeon Lee, Barnabé Agalati, and Raulston Gillette. 2023. "Development and Effectiveness of Agricultural Cooperatives: Case of Maize Producer Cooperatives (MPCs) in the Republic of Benin" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054480

APA StyleIbikoule, G. E., Lee, J., Agalati, B., & Gillette, R. (2023). Development and Effectiveness of Agricultural Cooperatives: Case of Maize Producer Cooperatives (MPCs) in the Republic of Benin. Sustainability, 15(5), 4480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054480