Migration and Return to Mapuche Lands in Southern Chile, 1970–2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

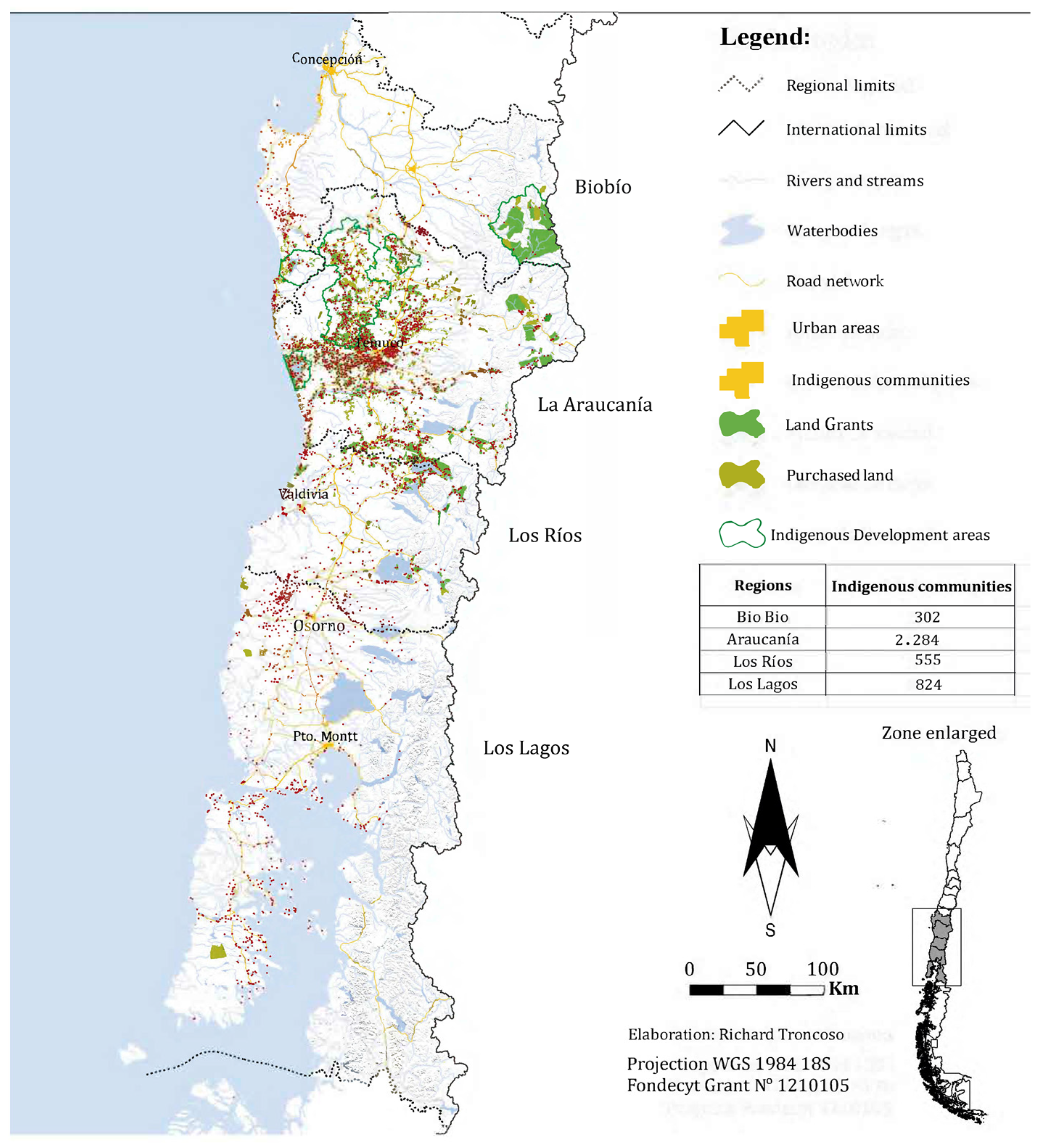

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Migration to the City, until the 1970s

2.2. Community Division by the Dictatorship, from 1979 to the Present

3. Results

3.1. The Crisis of Traditional Agriculture and the New Rural Spaces in Southern Chile, 1980–2022

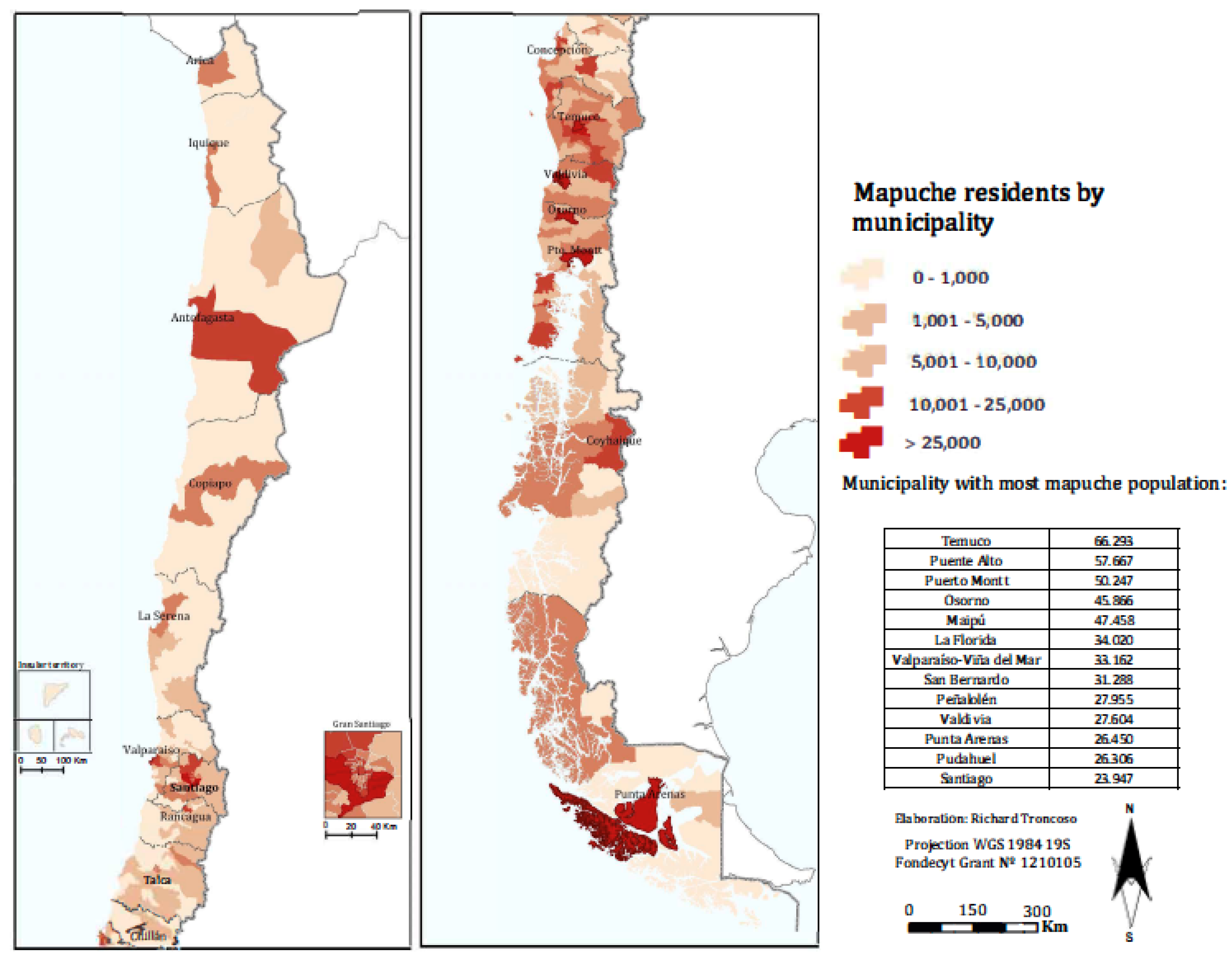

3.2. The Mapuche Diaspora in Recent Decades

3.3. Migration from the Cities to Mapuche Communities. The Return to the Land

“Alas for those timesthat we would continue tobe siblings,we would open our eyesto greet the morning.Mari Mari kom pu che, we would say,and we would still be earth and skybefore the gaze of nature” [60].

4. Discussion

4.1. Reasons for Return Migration

4.2. Effects of the Increased Number of Residents in the Communities

5. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Del Valle Ramos, C. Los nuevos moradores del mundo rural: Neorrurales en tiempos de despoblación en Andalucía. Perspect. Rural Dev. 2019, 3, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar de Corral, G. Nuevos Campesinos. La Producción Ecológica Alternativa. Estudio Antropológico Social de Experiencias Utópicas de Producción. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/696626 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Méndez, M. Una tipología de los nuevos habitantes del campo: Aportes para el estudio del fenómeno neorrural a partir del caso de Manizales, Colombia. RESR 2013, 51, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pileva, D.; Ivaylo, M. Counter-urbanization and “return” to rurality? Implications of COVID-19 pandemic in Bulgaria. Glas. Etnogr. Inst. SANU 2021, 69, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarz, N.; Rosenbaum-Feldbrügge, M.; Sander, N.; Sulak, H.; Knobloch, V. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on internal migration in Germany: A descriptive analysis. Popul. Space Place 2022, 28, e2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Leonardo, M.; Rowe, F.; Fresolone-Caparrós, A. Rural revival? The rise in internal migration to rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Who moved and Where? J. Rural Stud. 2022, 96, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ní Laoire, C. The “green green grass of home” Return migration to rural Ireland. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriola Vega, L.A. Return migration form the United States to Rural Areas of Campeche and Tabasco. Migr. Int. 2014, 7, 101–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Kuschminder, K. (Eds.) Handbook of Return Migration; Edward Elgard Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller Scarnato, J. Returning to their roots: Examining the reintegration experiences of returned Indigenous migrant youth in Guatemala. Int. Soc. Work 2020, 65, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, A. David Aniñir: Poesía y memoria mapuche. A Contra Corriente. Una Rev. Hist. Soc. Lit. América Lat. 2014, 11, 68–89. [Google Scholar]

- Aniñir Guilitraro, D. Mapurbe. Venganza a Raíz; Pehuén Editores: Santiago, Chile, 2009; ISBN 978-956-16-0802-3. [Google Scholar]

- CONADI (Archive of Indigenous Affairs, Temuco, Chile). Unpublished sources. Commune of Padre Las Casas, Grant Titles Nº 194, 197, 286, 376, 425-434, 457-459, 532, 536, 5976, 602, 615, 634, 641, 646, 667, 669, 672, 673, 675, 677-678, 680, 767, 770, 811, 812, 822, 876, 882-885, 913, 923, 960, 968, 979, 1011, 1012, 1018, 1022, 1026, 1037, 1053, 1054, 1059, 1062, 1064, 1071, 1102, 1104, 1105, 1107-1110, 1123, 1134, 1146, and 1165. Commune of Nueva Imperial, Grant titles Nº 120, 122-124, 127-129, 131, 133, 134, 138, 139, 141-144, 147, 148, 151-154, 157, 159-161, 164, 170-172, 174-176, 180-185, 191-193, 211, 219, 222, 224, 225, 227-231, 233, 242, 244, 246, 256, 257, 262, 309, 310, 442, 443, 683-684, 687, 689, 703, 709, 711-714, 717, 718, 720-731, 733, 734, 736, 761, 788, 793, 794, 801, 803-806, 825-829, 832, 837-839, 841, 842, 848, 850, 855, 857, 859, 861, 863, 864, 869, 870, 874, 877-878, 881, 887, 889, 893, 903, 904, 916, 955, 958, 962, 964, 969, 976, 982, 996, 1020, 1034, 1039-1041, 1044, 1055, 1072, 1101, 1111, 1115, 1130, 1131, 1133, 1143, 1155, 1172, 1181, 1187, 1247, 1248, 1308, 1337, 1342, 1416, 1417, 1419, 1422, 1447, 1461, 1528, 1534, 1539, 1540, 1545, 1548, 1557, 1600, 1645, 1654, 1666, 1667, 1678, 1683, 1746, 1766, 1922, 2160, 2163, 2390, 2446, 2486, 2504-2505, 2551, 2585, 2605, 2838, 2839, 2876, 2894, 2895, and 2931. Commune of Lautaro, Grant titles Nº 81, 83, 90, 98, 102, 115, 121, 234, 305, 306, 308, 398, 420, 423, 424, 449, 531, 664, 665, 668, 671, 676, 749, 764, 765, 769, 772-775, 777-781, 783-785, 819, 823, 836, 844-845, 849, 912, 918, 926-928, 943, 949, 950, 954, 963, 971-973, 983, 985, 990-992, 995, 1013, 1024, 1043, 1048 1052, 1057-1061, 1065-1067, 1069, 1073, 1076, 1081, 1087, 1090-1094, 1103, 1122, 1135, 1138, 1140, 1141, 1145, 1147, 1148, 1152, 1154, 1157-1160, 1167, 1169, 1177, 1178, 1180, 1182, 1184, 1186, 1208, 1210, 1220, 1224, 1231, 1241, 1251, 1252, 1272, 1289, 1291, 1294, 1307, 1309, 1360, 1412, 1423, 1457, 1583, 1586, 1595-1599, 1618, 1619, 1643, 1663, 1885, 2346, 2677, 2763, and 2803.

- Data in CONADI, Integrated Information System. Available online: https://siic.conadi.cl/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- INE. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2017; INE: Santiago, Chile, 2017; Available online: https://www.ine.cl/estadisticas/sociales/censos-de-poblacion-y-vivienda/informacion-historica-censo-de-poblacion-y-vivienda (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- INE. VIII Censo Agropecuario y Forestal, año Agrícola 2020–2021; INE: Santiago, Chile, 2021; Available online: https://www.ine.gob.cl/estadisticas/economia/agricultura-agroindustria-y-pesca/censos-agropecuarios (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Almonacid, F. La división de las comunidades indígenas del sur de Chile, 1925–1958: Un proyecto inconcluso. Rev. Indias 2008, LXVIII, 115–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoa, J. Historia del Pueblo Mapuche (Siglo XIX y XX); Ediciones Sur: Santiago, Chile, 1996; Available online: http://www.sitiosur.cl/detalle-de-la-publicacion/?PID=2653 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Bengoa, J. La Memoria Olvidada. Historia de Los Pueblos Indígenas de Chile; Cuadernos Bicentenario, Presidencia de la República: Santiago, Chile, 2004; ISBN 9567892040. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, M. La Historia del Despojo. El Origen de la Propiedad Particular en el Territorio Mapuche; Pehuén: Santiago, Chile, 2021; ISBN 978-956-16-0835-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pávez, J.; Payàs, G. El protectorado de indígenas en Chile. In Estudio Introductorio y Fuentes (1898–1923); Fuentes para la Historia de la República; Centro de Investigaciones Diego Barros Arana: Santiago, Chile, 2021; Volume LIII, ISBN 978-956-244-534. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, J. La Formación del Estado y la Nación, y el Pueblo Mapuche: De la Inclusión a la Exclusión; Centro de Investigaciones Diego Barros Arana: Santiago, Chile, 2003; ISBN 956-244-156-3. Available online: http://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/archivos2/pdfs/MC0027516.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Bello, A. Nampülkafe. El Viaje de los Mapuche Desde la Araucanía a las Pampas Argentinas; Territorio, Política y Cultura en Los Siglos XIX y XX; Ediciones UCT: Temuco, Chile, 2011; ISBN 978-956-7019-68-4. Available online: https://repositoriodigital.uct.cl/items/2f7816ca-0989-4598-8bf1-e262e0c5c251 (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Bello, A. Cordillera, naturaleza y territorialidades simbólicas entre los mapuche del siglo XIX. Scr. Philos. Nat. 2014, 6, 21–33. Available online: https://scriptaphilosophiaenaturalis.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/c3a1lvaro-bello-cordillera-naturaleza-y-territorialidades-simbc3b3licas-entre-los-mapuche-del-siglo-xix1.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Almonacid, F. Comercio e Integración entre Chile y Argentina en la Zona Sur: Estado y Sociedad Regional (1930–1960). In Araucanía, Siglos XIX y XX. Economía, Migraciones y Marginalidad; Pinto, J., Ed.; Universidad de Los Lagos: Osorno, Chile, 2011; pp. 199–230. ISBN 978-956-8709-45-7. [Google Scholar]

- Data of IDE Chile. Available online: https://www.ide.cl/index.php (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Bengoa, J. El Campesinado Chileno Después de la Reforma Agraria; Ediciones Sur: Santiago, Chile, 1983; Available online: https://www.sitiosur.cl/detalle-de-la-publicacion/?el-campesinado-chileno-despues-de-la-reforma-agraria (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Bengoa, J.; Valenzuela, E. Economía Mapuche. Pobreza y Subsistencia en la Sociedad Mapuche Contemporánea; Editorial PAS: Santiago, Chile, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- García Mingo, E. Zomo Newen. Relatos de Vida de Mujeres Mapuche en su Lucha por los Derechos Indígenas; Lom Ediciones: Santiago, Chile, 2018; ISBN 978-956-0009-73-9. [Google Scholar]

- Manquel, R.; (Woman, Chief of Staff, Municipality of Padre Las Casas, Padre Las Casas, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Melinao, S.; (Man, President of the Chureo Sandoval community, Truf Truf, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Gundermann, H.; González, H.; De Ruyt, L. Migración y movilidad mapuche a la Patagonia Argentina. Magallania 2009, 37, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almonacid, F.; Stahl, D. Memorias de la Violencia y Justicia en el sur de Chile. Entrevistas Biográficas con Dirigentes de Derechos Humanos; Inolas Publishers: Postdam, Germany, 2021; pp. 295–333. ISBN 978-3-946139-71-3. [Google Scholar]

- Foerster, R.; Montecino, S. Organizaciones, Líderes y Contiendas Mapuches (1900–1970); CEM: Santiago, Chile, 1988. Available online: https://www.memoriachilena.gob.cl/602/w3-article-9602.html (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Paillalef, J. Los Mapuche y el Proceso que los Convirtió en Indios. Psicología de la Discriminación; Catalonia: Santiago, Chile, 2018; ISBN 978-956-324-692-6. [Google Scholar]

- Haughney, D. Neoliberal Economics, Democratic Transition, and Mapuche Demands for Rights in Chile; Univesity Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 25–35. ISBN 0-8130-2938-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mallon, F. La Sangre del Copihue. La Comunidad Mapuche de Nicolás Ailío y el Estado Chileno, 1906–2001; Lom Ediciones: Santiago, Chile, 2004; pp. 61–88. ISBN 956-282-686-4. [Google Scholar]

- Samaniego, A.; Ruiz Rodríguez, C. Mentalidades y Políticas Wingka: Pueblo Mapuche, Entre Golpe u Golpe (De Ibañez a Pinochet); CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2007; ISBN 978-840-0085-69-8.

- Crow, J. The Mapuche in Modern Chile. A Cultural History; University Press of Florida: Geinsville, FL, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-8130-4428-6. [Google Scholar]

- Henríquez Jaramillo, L. Cinco décadas de transformaciones en la Araucanía rural. Polis 2014, 34, 982. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/polis/8802 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Saavedra, A. Transformaciones de la Población Mapuche en el Siglo XX; Lom Ediciones: Santiago, Chile, 2006; ISBN 978-956-3104-51-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pincheira, E.; (Woman, Intercultural Educator, Maquehue, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Bengoa, J. Sociedad Mapuche Rural: 40 años. Le Monde Diplomatique. Edición Chilena, 16 de Agosto de 2020. Available online: https://www.lemondediplomatique.cl/sociedad-mapuche-rural-40-anos-por-jose-bengoa.html (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Almonacid, F. Neoliberalismo y Globalización en la Agricultura del sur de Chile, 1973–2019; Ediciones Universitarias de Valparaíso: Valparaíso, Chile, 2020; ISBN 978-956-17-0858-7. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, M.; Mella, E. Las Razones del Illkún/Enojo. Memoria, Despojo y Criminalización en el Territorio Mapuche de Malleco; Lom Ediciones: Santiago, Chile, 2010; ISBN 978-956-0001-51-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, S.; Echenique, J. La Agricultura Chilena: Las dos Caras de la Modernización; FLACSO: Santiago, Chile, 1988; ISBN 956-205-028. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, R.; (Man, Resident in Juan Coñoenao community, Maquehue, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Huilipán, P.; (Man, President of the Ignacio Huina community, Maquehue, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Manqueñir, E.; (Woman, President of the Miguel Huichañir Community, Maquehue, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Pairicán, F. Malón. La Rebelión del Movimiento Mapuche, 1990–2013; Pehuén: Santiago, Chile, 2014; ISBN 978-956-16-0610-4. [Google Scholar]

- Marchant, C.; Felipe Aros, F. Nuevas movilidades en los espacios rurales de la Araucanía andina. Rev. Líder 2018, 20, 9–40. Available online: https://revistaliderchile.com/index.php/liderchile/article/view/24/33 (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Zunino, H.; Hidalgo, R. En busca de la utopía verde: Migrantes de amenidad en la comuna de Pucón, IX región de La Araucanía, Chile. Scr. Nova 2010, XIV, 331. Available online: https://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-331/sn-331-75.htm (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Instituto de Estudios Indígenas/UFRO; INE; CONADI; CEPAL; CELADE. XVI Censo Nacional de Población 1992. Población Mapuche. Tabulaciones Especiales. Total País, Región Metropolitana y Región de La Araucanía; Universidad de La Frontera: Temuco, Chile, 1998; Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/7439?show=full (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- CONADI, Integrated Information System, Studies Unit, from CASEN 2015. Available online: https://siic.conadi.cl/ (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Millaqueo, R.; (Woman, President of the Manuel Coilla community, Maquehue, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Painenao, M.; (Woman, Resident in Juan Coñoenao community, Maquehue, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Huenupán, E.; (Man, Former president of APICOOP cooperative, Lago Ranco, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Ancán Jara, J.; Calfío Montalva, M. “El retorno al país mapuche. Reflexiones preliminares para una utopía por construir”. In Proceedings of the III Congreso Chileno de Antropología, Temuco, Chile, 9–13 November 1998; Available online: https://www.aacademica.org/iii.congreso.chileno.de.antropologia/113 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Vergara, J.; Gundermann, H.; Foerster, R. Estado, Conflicto étnico y Cultura. Estudios Sobre Pueblos Indígenas en Chile; Ocho libros Editores: Santiago, Chile, 2013; pp. 118–146. ISBN 978-956-287-348-2. [Google Scholar]

- Catrileo, M. El Abrazo del Viento; Editorial Quimantú: Santiago, Chile, 2014; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- González, A.; (Woman, Social assistant, Social Department, Municipality of San Juan de la Costa, Puaucho, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Lazcano, M.; (Man, Agronomist, Indigenous Territorial Development Program (PDTI), Municipality of Cunco, Cunco, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Painicura, S.; (Man, PDTI Coordinator, Municipality of Nueva Imperial, Nueva Imperial, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Sotomayor, S.; (Woman, PDTI Coordinator, Municipality of Lautaro, Lautaro, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Ladino, J.; (Man, President of the Juan Coñoenao community, Maquehue, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Almonacid, F. El desarrollo desigual y contradictorio manifestado espacialmente en el sur de Chile. In Historia y Prospectiva; Cavieres, E., Pérez Herrero, P., Eds.; Editorial Marcial Pons: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 235–259. ISBN 978-84-9123-863-8. [Google Scholar]

- Arias Maldonado, M. Desde las Ruinas del Futuro. Teoría Política de la Pandemia; Editorial Taurus: Madrid, Spain, 2020; ISBN 978-84-3062-380-8. [Google Scholar]

- Boccardo, G. Trabajar en tiempos de pandemia: ¿Antesala de nuestro futuro laboral? Estado, pandemia y crisis social. Rev. An. 2020, 17, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Cham, G.; Herrera Lima, S.; Kemner, J. (Eds.) Pandemia y Crisis. El COVID-19 en América Latina; CALAS; Editorial Universidad de Guadalajara: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2021; ISBN 978-607-571-140-9. [Google Scholar]

- Simón, P. Corona. Política en Tiempos de Pandemia; Editorial Debate: Barcelona, Spain, 2020; ISBN 978-84-1800-689-0. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado Lincopi, C. Mapurbekistán. De Indios a Mapurbes en la Capital del Reyno. Racismo, Segregación Urbana y Agencias Mapuche en Santiago de Chile. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Spain, 2016. Available online: https://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/tesis/te.1358/te.1358.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Queupumil, H.; (Man, Agronomist, PDTI Coordinator, Municipality of Padre Las Casas, Padre Las Casas, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Penchuleo Morales, L. (National Director of CONADI, Temuco, Chile). Private Communication, Letter Nº 508, 26 January 2023.

- Llanos, R.; (Man, Neighborhood leader, commune of San Juan de la Costa, Maicolpué, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Vargas, U.; (Woman, President of RWA, Municipality of San Juan de la Costa, Puaucho, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Beltrán, P.; (Man, PDTI technician, Municipality of Lautaro, Lautaro, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Domínguez, M.; (Man, Local Development Program (PRODESAL) Coordinator, Municipality of San Juan de la Costa, Puaucho, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Pacheco, I.; (Man, PDTI technician, Municipality of Lautaro, Lautaro, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Romero, R.; (Woman, Resident in Juan Paillao community, commune of Cunco, Chile). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Castillo, C.; (Territorial Management, PDTI, Municipality of Nueva Imperial). Personal Communication, 2022.

- Rivas, S. Tierras Indígenas. El 35% de los Habitantes de La Araucanía Vive en Zonas que Están Dentro de un Título de Merced, 22 de Mayo de 2022. Diario La Tercera. Available online: https://www.latercera.com/investigacion-y-datos/noticia/tierras-indigenas-el-35-de-los-habitantes-de-la-araucania-vive-en-zonas-que-estan-dentro-de-un-titulo-de-merced/LW5NSUL7NBE7ZJNXW2ABFZEERI/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Quiñones Díaz, X.; Gálvez Díaz, J. Estimación y estructura de los ingresos de familias mapuches rurales de zonas periurbanas de Temuco, Chile. Mundo Agrar. 2015, 16, 32. Available online: https://www.mundoagrario.unlp.edu.ar/article/view/MAv16n32a07/6861 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Briceño Olivera, C.; Tereucán Angulo, J.; Hauri Opazo, S. Ingreso y empleo en la población mapuche rural y pobre en cuatro regiones del sur de Chile. TS Cuad. De Trab. Soc. 2017, 16, 76–98. Available online: http://www.tscuadernosdetrabajosocial.cl/index.php/TS/article/view/140/138 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Cuevas Valdés, P. Relaciones entre el perfil de ingresos de las unidades domésticas y los salarios en el agro de Chile y Mexico. Rev. Austral Cienc. Soc. 2020, 38, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Urban Population | Rural Population | Total Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biobío | 79,839 | 24,600 | 104,439 |

| Araucanía | 126,430 | 185,029 | 311,459 |

| Los Ríos | 40,021 | 36,239 | 76,260 |

| Los Lagos | 132,678 | 75,216 | 207,894 |

| Total | 378,968 | 321,084 | 700,052 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almonacid, F. Migration and Return to Mapuche Lands in Southern Chile, 1970–2022. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054457

Almonacid F. Migration and Return to Mapuche Lands in Southern Chile, 1970–2022. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054457

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmonacid, Fabián. 2023. "Migration and Return to Mapuche Lands in Southern Chile, 1970–2022" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054457

APA StyleAlmonacid, F. (2023). Migration and Return to Mapuche Lands in Southern Chile, 1970–2022. Sustainability, 15(5), 4457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054457