Perspectives on the Impact of E-Learning Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic—The Case of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Effect of Electronic Learning on Electronic Commerce

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Design and Participants

3.2. Survey Classification Factors

3.3. Data Analysis Techniques and Statistical Methods

4. Results and Analyses

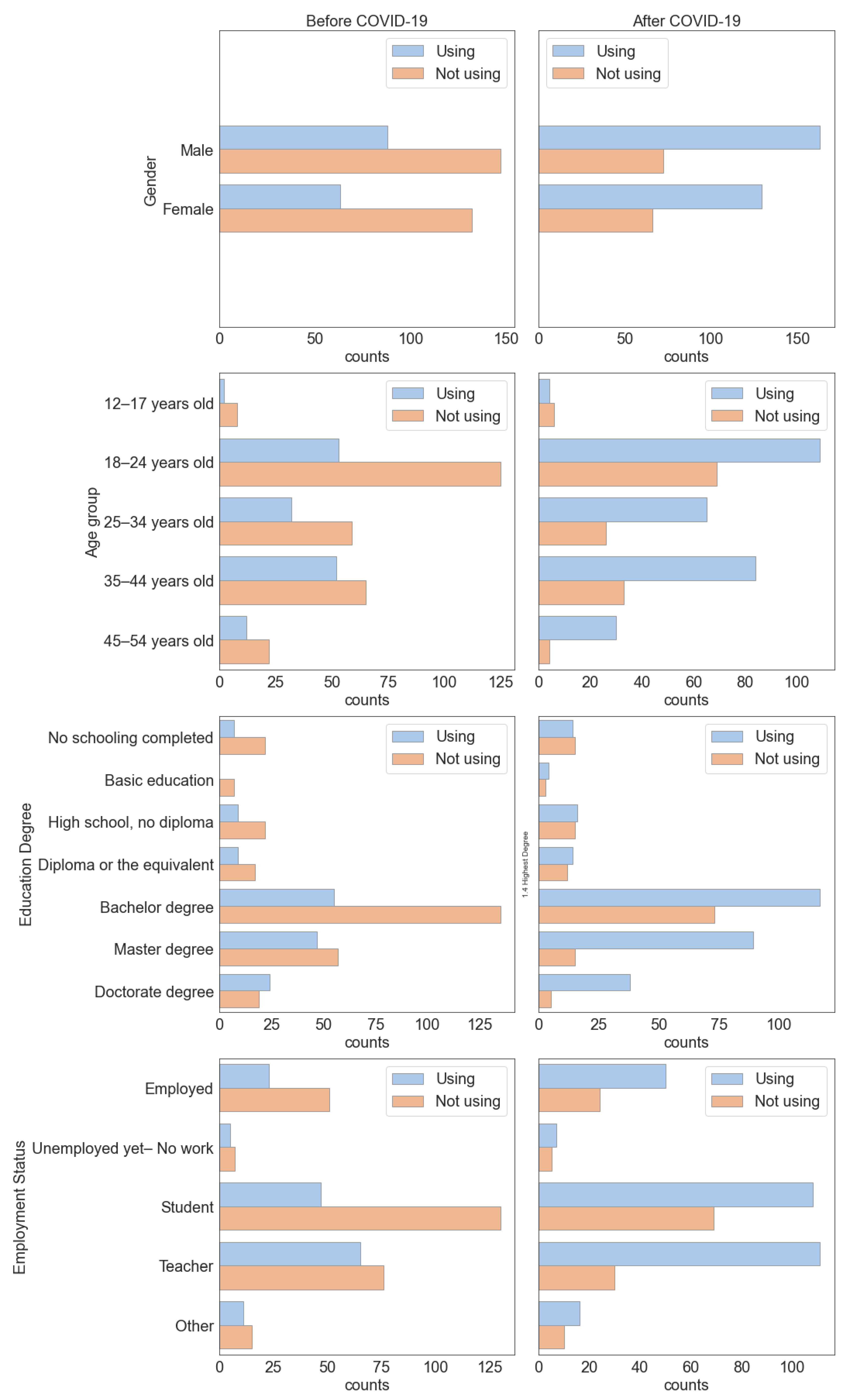

4.1. Results of Socio-Demographic Variables

4.2. Effect of COVID-19 on Electronic Learning

4.3. Analysis of the Statistical Relationship between Personal Employment Status and Basic E-Learning Features after the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.4. The Impact of Electronic Learning on Adaptive Skills

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Studies

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, Y.-P.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Ooi, K.-B.; Lim, W.-L. Can COVID-19 Pandemic Influence Experience Response in Mobile Learning? Telemat. Inform. 2021, 64, 101676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoud, A.R.; Harasis, A.A. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Student’s e-Learning Experience in Jordan. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1404–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, R.S.; Kabir, G. Satisfaction of E-Learners with Electronic Learning Service Quality Using the SERVQUAL Model. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radu, M.-C.; Schnakovszky, C.; Herghelegiu, E.; Ciubotariu, V.-A.; Cristea, I. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Quality of Educational Process: A Student Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R. A Literature Review on Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Teaching and Learning. High. Educ. Future 2021, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, A.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, F. How Would the COVID-19 Pandemic Reshape Retail Real Estate and High Streets through Acceleration of E-Commerce and Digitalization? J. Urban Manag. 2021, 10, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Hermida, A.P. College Students’ Use and Acceptance of Emergency Online Learning Due to COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2020, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, D.; Zhu, L.; Benwell, B.; Yan, Z. Digital Technology Use during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Review. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Muff, A.; Meschiany, G.; Lev-Ari, S. Adequacy of Web-Based Activities as a Substitute for in-Person Activities for Older Persons during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.Y.; Ali, B.J.; Top, C. Understanding the Impact of Trust, Perceived Risk, and Perceived Technology on the Online Shopping Intentions: Case Study in Kurdistan Region of Iraq. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2021, 27, 2136–2153. [Google Scholar]

- Petronzi, R.; Petronzi, D. The Online and Campus (OaC) Model as a Sustainable Blended Approach to Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: A Response to COVID-19. J. Pedagog. Res. 2020, 4, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holotescu, C.; Grosseck, G.; Andone, D.; Gunesch, L.; Constandache, L.; Nedelcu, V.D.; Ivanova, M.S.; Dumbrăveanu, R. Romanian Educational System Response during the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the eLearning and Software for Education Conference, Bucharest, Romania, 23–24 April 2020; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Córdoba, P.-J.; Benito, B.; García-Sánchez, I.-M. Efficiency in the Governance of the Covid-19 Pandemic: Political and Territorial Factors. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanec, T.P. The Lack of Academic Social Interactions and Students’ Learning Difficulties during COVID-19 Faculty Lockdowns in Croatia: The Mediating Role of the Perceived Sense of Life Disruption Caused by the Pandemic and the Adjustment to Online Studying. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.L.; Zhang, S. From Fighting COVID-19 Pandemic to Tackling Sustainable Development Goals: An Opportunity for Responsible Information Systems Research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouratidis, K.; Papagiannakis, A. COVID-19, Internet, and Mobility: The Rise of Telework, Telehealth, e-Learning, and e-Shopping. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xhelili, P.; Ibrahimi, E.; Rruci, E.; Sheme, K. Adaptation and Perception of Online Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic by Albanian University Students. Int. J. Stud. Educ. 2021, 3, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Peters, S. COVID-19 Impact on Teleactivities: Role of Built Environment and Implications for Mobility. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2022, 158, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabduljabbar, A.; Aksoy, M. The Effect of COVID-19 on E-Commerce and E-Learning. Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR) 2021, 10, 751–755. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, S.; Ślusarczyk, B.; Hajizada, S.; Kovalyova, I.; Sakhbieva, A. Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Online Consumer Purchasing Behavior. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2263–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, H.; Fang Yie, L.; Mohiddin, F.; Rahman Setiawan, A.A.; Haghi, P.K.; Setiana, D. Revealing Social Media Phenomenon in Time of COVID-19 Pandemic for Boosting Start-up Businesses through Digital Ecosystem. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2021, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, C.; Fosso-Wamba, S.; Arnaud, J.B. Online Consumer Resilience during a Pandemic: An Exploratory Study of e-Commerce Behavior before, during and after a COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, T.N. Examining the Influence of Covid 19 Pandemic in Changing Customers’ Orientation towards e-Shopping. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2020, 14, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson-Szlezak, P.; Reeves, M.; Swartz, P. What Coronavirus Could Mean for the Global Economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Redwood, R.; Kitchin, R.; Apostolopoulou, E.; Rickards, L.; Blackman, T.; Crampton, J.; Rossi, U.; Buckley, M. Geographies of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akour, I.; Alshurideh, M.; al Kurdi, B.; al Ali, A.; Salloum, S. Using Machine Learning Algorithms to Predict People’s Intention to Use Mobile Learning Platforms during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Machine Learning Approach. JMIR Med. Educ. 2021, 7, e24032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, D.L.; Coombs, C.; Constantiou, I.; Duan, Y.; Edwards, J.S.; Gupta, B.; Lal, B.; Misra, S.; Prashant, P. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Information Management Research and Practice: Transforming Education, Work and Life. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, K.V.; Sankar, J.P.; Kalaichelvi, R.; John, J.A.; Menon, N.; Alqahtani, M.S.M.; Abumelha, M.A. Factors Affecting the Quality of E-Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic from the Perspective of Higher Education Students. COVID-19 Educ. Learn. Teach. A Pandemic-Constrained Environ. 2020, 19, 731–753. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, C.; Baber, H.; Kumar, P. Examining the Moderating Effect of Perceived Benefits of Maintaining Social Distance on E-Learning Quality during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2021, 49, 532–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherheș, V.; Stoian, C.E.; Fărcașiu, M.A.; Stanici, M. E-Learning vs. Face-to-Face Learning: Analyzing Students’ Preferences and Behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexa, L.; Avasilcai, S.; Pislaru, M.; Bujor, A.; Avram, E.; Lucescu, L. Exploring Romanian Engineering Students’ Perceptions of Covid-19 Emergency e-Learning Situation. A Mixed-Method Case Study. Electron. J. E-Learn. 2022, 20, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Antuñano, M.A.; Rodríguez-Reséndiz, J.; Rodriguez Segura, L.; Cruz Perez, M.A.; Altamirano Corro, J.A.; Paredes-Garcia, W.J.; Rodríguez-Reséndiz, H. Analysis of Emergency Remote Education in COVID-19 Crisis Focused on the Perception of the Teachers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Learning from E-Commerce for E-Learning. In Proceedings of the 2007 First IEEE International Symposium on Information Technologies and Applications in Education, Kunming, China, 23–25 November 2007; Curran Associates: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Balida, A.R.; Encarnacion, R. Challenges and Relationships of E-Learning Tools to Teaching and Learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on E-Learning, Berlin, Germany, 28–30 October 2020; Academic Conferences International: Berlin, Germany, 2020; p. 48-XIX. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Persistence and Attrition among Participants in a Multi-Page Online Survey Recruited via Reddit’s Social Media Network. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahintürk, L.; Özcan, B. The Comparison of Hypothesis Tests Determining Normality and Similarity of Samples. J. Nav. Sci. Eng. 2017, 13, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Soong, T.R.; Milner, D.A., Jr. Comparative Statistics. In Statistics for Pathologists; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 39. [Google Scholar]

- Ostertagova, E.; Ostertag, O.; Kováč, J. Methodology and Application of the Kruskal-Wallis Test. In Applied Mechanics and Materials; Trans Tech Publications: Wollerau, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 611, pp. 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.S.; Santos, N.C.; Cunha, P.; Cotter, J.; Sousa, N. The Use of Multiple Correspondence Analysis to Explore Associations between Categories of Qualitative Variables in Healthy Ageing. J. Aging Res. 2013, 2013, 302163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.; Korotayev, A. Statistical Analysis of Cross-Tabs. Anthrosciences.org, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dura, C.; Drigă, I. Application of Chi Square Test in Marketing Research. Ann. Univ. Petroşani. Econ. 2017, 17, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Ismagilova, E.; Hughes, D.L.; Carlson, J.; Filieri, R.; Jacobson, J.; Jain, V.; Karjaluoto, H.; Kefi, H.; Krishen, A.S. Setting the Future of Digital and Social Media Marketing Research: Perspectives and Research Propositions. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maroof, R.S.; Alhumaid, K.; Akour, I.; Salloum, S. Factors That Affect E-Learning Platforms after the Spread of COVID-19: Post Acceptance Study. Data 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofijur, M.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Alam, M.A.; Islam, A.B.M.S.; Ong, H.C.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Najafi, G.; Ahmed, S.F.; Uddin, M.A.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Impact of COVID-19 on the Social, Economic, Environmental and Energy Domains: Lessons Learnt from a Global Pandemic. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Li, J.-P.; Chu, C.-C.; Dinca, G. Impact of COVID-19 on Transportation and Logistics: A Case of China. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2021, 35, 2386–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coman, C.; Țîru, L.G.; Meseșan-Schmitz, L.; Stanciu, C.; Bularca, M.C. Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education during the Coronavirus Pandemic: Students’ Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maatuk, A.M.; Elberkawi, E.K.; Aljawarneh, S.; Rashaideh, H.; Alharbi, H. The COVID-19 Pandemic and E-Learning: Challenges and Opportunities from the Perspective of Students and Instructors. J. Comput. High Educ. 2022, 34, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Wu, H. Synchronous Online Learning During COVID-19: Chinese University EFL Students’ Perspectives. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221094820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenz, M.A.; Schmidt, A.; Wöstmann, B.; Krämer, N.; Schulz-Weidner, N. Students’ and Lecturers’ Perspective on the Implementation of Online Learning in Dental Education Due to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilleri, M.A.; Camilleri, A.C. Remote Learning via Video Conferencing Technologies: Implications for Research and Practice. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahyoob, M. Challenges of E-Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic Experienced by EFL Learners. Arab. World Engl. J. (AWEJ) 2020, 11, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Kusumaningrum, B.; Yulia, Y.; Widodo, S.A. Challenges during the Pandemic: Use of e-Learning in Mathematics Learning in Higher Education. Infin. J. 2020, 9, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grynyuk, S.; Kovtun, O.; Sultanova, L.; Zheludenko, M.; Zasluzhena, A.; Zaytseva, I. Distance Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Experience of Ukraine’s Higher Education System. Electron. J. e-Learn. 2022, 20, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornkitvikai, Y.; Tham, S.Y.; Harvie, C.; Buachoom, W.W. Barriers and Factors Affecting the E-Commerce Sustainability of Thai Micro-, Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises (MSMEs). Sustainability 2022, 14, 8476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.H.; Saffu, K.; Mazurek, M. An Empirical Study of Factors Influencing E-Commerce Adoption/Non-Adoption in Slovakian SMEs. J. Internet Commer. 2016, 15, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.J. Impact of COVID-19 on Consumer Buying Behavior toward Online Shopping in Iraq. Econ. Stud. J. 2020, 18, 267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sibahee, E.; Halim, R.; Ramadani, H.; Jamal, M. Online Shopping: A Glimpse into the Iraqi Customer Shopping Behavior. Available online: https://bit.ly/3KXsV3g (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Gupta, V.; Jain, N. Harnessing Information and Communication Technologies for Effective Knowledge Creation: Shaping the Future of Education. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2017, 30, 831–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costado Dios, M.T.; Piñero Charlo, J.C. Face-to-Face vs. e-Learning Models in the COVID-19 Era: Survey Research in a Spanish University. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colreavy-Donelly, S.; Ryan, A.; O’Connor, S.; Caraffini, F.; Kuhn, S.; Hasshu, S. A Proposed VR Platform for Supporting Blended Learning Post COVID-19. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhang, L.; Liang, Y. Online Blended Learning in Small Private Online Course. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fodeh, R.S.; Alwahadni, A.M.S.; Abu Alhaija, E.S.; Bani-Hani, T.; Ali, K.; Daher, S.O.; Daher, H.O. Quality, Effectiveness and Outcome of Blended Learning in Dental Education during the Covid Pandemic: Prospects of a Post-Pandemic Implementation. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitthiworachart, J.; Joy, M.; Mason, J. Blended Learning Activities in an E-Business Course. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, A. Impact of Digital Social Media on Indian Higher Education: Alternative Approaches of Online Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2020, 10, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amin, M.; al Zubayer, A.; Deb, B.; Hasan, M. Status of Tertiary Level Online Class in Bangladesh: Students’ Response on Preparedness, Participation and Classroom Activities. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.T.; Hagsten, E. When International Academic Conferences Go Virtual. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Li, W.; Qin, M.; Cheng, M. Understanding Students’ Acceptance and Usage Behaviors of Online Learning in Mandatory Contexts: A Three-Wave Longitudinal Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatani, T.H. Student Satisfaction with Videoconferencing Teaching Quality during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cendra, A.N.; Sulindra, E. Navigating Teaching during Pandemic: The Use of Discussion Forum in Business English Writing Class. ELTR J. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, H.; Altinpulluk, H. Discussion Forums as a Learning Material in Higher Education Institutions. Int. J. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2021, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-Y.; Ying, L.U. Decision Tree Methods: Applications for Classification and Prediction. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, A. Long Short-Term Memory. In Supervised Sequence Labelling with Recurrent Neural Networks; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Gandomi, A.H. The Colony Predation Algorithm. J. Bionic Eng. 2021, 18, 674–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, C.M.; Rashid, T.A. A New Evolutionary Algorithm: Learner Performance Based Behavior Algorithm. Egypt. Inform. J. 2021, 22, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, J.M.; Ahmed, T. Fitness Dependent Optimizer: Inspired by the Bee Swarming Reproductive Process. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 43473–43486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, D.O.; Aladdin, A.M.; Talabani, H.S.; Rashid, T.A.; Mirjalili, S. The Fifteen Puzzle—A New Approach through Hybridizing Three Heuristics Methods. Computers 2023, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrancea, L.-M.; Batrancea, I.; Moscviciov, A. The Roots of the World Financial Crisis. Ann. Univ. Oradea Econ. Sci. 2009, 3, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Moscviciov, A.; Batrancea, I.; Batrancea, M.; Batrancea, L. Financial Ratio Analysis Used in the IT Enterprises. Ann. Univ. Oradea Econ. Sci. 2010, 1, 600–603. [Google Scholar]

- Batrancea, L.; Batrancea, I.; Moscviciov, A. The Analysis of the Entity’s Liquidity—A Means of Evaluating Cash Flow. J. Int. Financ. Econ. 2009, 9, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Batrancea, L.M. An Econometric Approach on Performance, Assets, and Liabilities in a Sample of Banks from Europe, Israel, United States of America, and Canada. Mathematics 2021, 9, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichita, R.-A.; Bătrâncea, L.-M. The Implications of Tax Morale on Tax Compliance Behavior. Ann. Univ. Oradea Econ. Sci. 2012, 21, 739–744. [Google Scholar]

- Batrancea, L.; Nichita, R.; Batrancea, I. Tax Non-Compliance Behavior in the Light of Tax Law Complexity and the Relationship between Authorities and Taxpayers. Sci. Ann. “Al. I. Cuza” Univ.-Econ. 2012, 59, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagurney, A. I Have to Go Online Next Week?! Practical Suggestions Based on Ke (2016). Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Features | Total Sample | EL before COVID-19 | EL after COVID-19 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using | Not Using | Statistics | Using | Not Using | Statistics | ||

| n = 430 | 151 (35.1%) | 279 (64.9%) | 292 (67.9%) | 138 (32.1%) | |||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 235 (54.7%) | 88 (37.4%) | 147 (62.6%) | χ2 (1) = 1.02, p = 0.313 | 163 (69.4%) | 72 (30.6%) | χ2 (1) = 0.367, p = 0.545 |

| Female | 195 (45.3%) | 63 (32.3%) | 132 (67.7%) | 129 (66.2%) | 66 (33.8%) | ||

| Age Group | |||||||

| 12–17 years old | 10 (2.3%) | 2 (20.0%) | 8 (80.0%) | χ2 (4) = 7.7, p = 0.103 | 4 (40.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | χ2 (4) = 14.985, p = 0.005 |

| 18–24 years old | 178 (41.4%) | 53 (29.8%) | 125 (70.2%) | 109 (61.2%) | 69 (38.8%) | ||

| 25–34 years old | 91 (21.2%) | 32 (35.2%) | 59 (64.8%) | 65 (71.4%) | 26 (28.6%) | ||

| 35–44 years old | 117 (27.2%) | 52 (44.4%) | 65 (55.6%) | 84 (71.8%) | 33 (28.2%) | ||

| 45–54 years old | 34 (7.9%) | 12 (35.3%) | 22 (64.7%) | 30 (88.2%) | 4 (11.8%) | ||

| Degree of Education | |||||||

| No schooling completed | 29 (6.7%) | 7 (24.1%) | 22 (75.9%) | χ2 (6) = 21.72, p = 0.00136 | 14 (48.3%) | 15 (51.7%) | χ2 (6) = 38.29, p = 0.000001 |

| Primary (basic education) | 7 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (100.0%) | 4 (57.1%) | 3 (42.9%) | ||

| High school, no diploma | 31 (7.2%) | 9 (29.0%) | 22 (71.0%) | 16 (51.6%) | 15 (48.4%) | ||

| High school, diploma or the equivalent | 26 (6.0%) | 9 (34.6%) | 17 (65.4%) | 14 (53.8%) | 12 (46.2%) | ||

| Bachelor degree | 190 (44.2%) | 55 (28.9%) | 135 (71.1%) | 117 (61.6%) | 73 (38.4%) | ||

| Master degree | 104 (24.2%) | 47 (45.2%) | 57 (54.8%) | 89 (85.6%) | 15 (14.4%) | ||

| Doctorate degree | 43 (10.0%) | 24 (55.8%) | 19 (44.2%) | 38 (88.4%) | 5 (11.6%) | ||

| Employment status | |||||||

| Employed | 74 (17.2%) | 23 (31.1%) | 51 (68.9%) | χ2 (4) = 14.51, p = 0.006 | 50 (67.6%) | 24 (32.4%) | χ2 (4) = 12.417, p = 0.015 |

| Unemployed (no work) | 12 (2.8%) | 5 (41.7%) | 7 (58.3%) | 7 (58.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | ||

| Student | 177 (41.2%) | 47 (26.6%) | 130 (73.4%) | 108 (61.0%) | 69 (39.0%) | ||

| Teacher | 141 (32.8%) | 65 (46.1%) | 76 (53.9%) | 111 (78.7%) | 30 (21.3%) | ||

| Other | 26 (6.0%) | 11 (42.3%) | 15 (57.7%) | 16 (61.5%) | 10 (38.5%) | ||

| Classification Features | Before COVID-19 | Classification Features | After COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 151 | n = 292 | |||

| The most popular EL method used | Synchronous online learning | 49 (32.5%) | Synchronous online learning | 105 (36.0%) |

| Asynchronous online learning | 27 (17.9%) | Asynchronous online learning | 50 (17.1%) | |

| Linear e-learning | 27 (17.9%) | Linear e-learning | 33 (11.3%) | |

| Interactive online learning | 29 (19.2%) | Interactive online learning | 89 (30.5%) | |

| Others | 19 (12.6%) | Others | 15 (5.1%) | |

| The most preferred device used for the EL method | Smartphone | 57 (37.7%) | Smartphone | 115 (39.4%) |

| Tablet | 2 (1.3%) | Tablet | 7 (2.4%) | |

| Laptop | 81 (53.6%) | Laptop | 155 (53.1%) | |

| Desktop | 11 (7.3%) | Desktop | 14 (4.8%) | |

| Others | 0 (0) | Others | 1 (0.3%) | |

| The scope or level of the EL method used | General education | 74 (49.0%) | General education | 124 (42.5%) |

| Training session | 23 (15.2%) | Training session | 40 (13.7%) | |

| Companies or organizations | 6 (4.0%) | Companies or organizations | 11 (3.8%) | |

| Conferences, seminars, workshops, or symposiums | 30 (19.9%) | Conferences, seminars, workshops, or symposiums | 73 (25.0%) | |

| Others | 18 (11.9%) | Others | 44 (15.1%) | |

| The period of using EL as an instructional platform | Approximately one year | 71 (47.0%) | Approximately six months | 82 (28.1%) |

| Approximately two years | 35 (23.2%) | Approximately one year | 60 (20.5%) | |

| Approximately three years | 11 (7.3%) | Approximately two years | 55 (18.8%) | |

| Approximately four years | 10 (6.6%) | Until now | 95 (32.5%) | |

| More than four years | 24 (15.9%) |

| Classification Features | Before COVID-19 | After COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| Learning management systems (LMSs) (Moodle; Google Classroom; Edmodo; Adobe Captivate Prime) | 69 (34.7%) | 143 (35.6%) |

| Mobile tools as an e-learning platform (Viber; WhatsApp; Telegram; Messenger; WeChat) | 61 (30.7%) | 87 (21.6%) |

| Virtual classroom software (Newrow Smart; Blackboard Collaborate) | 17 (8.5%) | 37 (9.2%) |

| Web conferencing and webinar tools (Zoom Meetings; Google Meet) | 52 (26.1%) | 135 (33.6%) |

| Features | Classification Features | After COVID-19 | Statistical Models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student | Teacher | Employed | Unemployed | Other | |||

| The most popular EL method used | Synchronous online learning | 41 (38.0%) | 36 (32.4%) | 21 (42.0%) | 3 (42.9%) | 4 (25.0%) | χ2 (16) = 26.159, p = 0.052 |

| Asynchronous online learning | 13 (12.0%) | 26 (23.4%) | 3 (6.0%) | 4 (57.1%) | 4 (25.0%) | ||

| Linear e-learning | 14 (13.0%) | 13 (11.7%) | 4 (8.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | ||

| Interactive online learning | 37 (34.3%) | 29 (26.1%) | 19 (38.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (25.0%) | ||

| Others | 3 (2.8%) | 7 (6.3%) | 3 (6.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | ||

| The most preferred device used for the EL method | Smartphone | 51 (47.2%) | 28 (25.2%) | 22 (44.0%) | 4 (57.1%) | 10 (62.5%) | χ2 (16) = 26.833, p = 0.043 |

| Tablet | 2 (1.9%) | 4 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (6.2%) | ||

| Laptop | 47 (43.5%) | 76 (68.5%) | 25 (50.0%) | 3 (42.9%) | 4 (25.0%) | ||

| Desktop | 7 (6.5%) | 3 (2.7%) | 3 (6.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (6.2%) | ||

| Others | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| The scope or level of the EL method utilized | General education | 51 (47.2%) | 48 (43.2%) | 17 (34.0%) | 2 (28.6%) | 6 (37.5%) | χ2 (16) =58.37, p = 0.000001 |

| Training session | 13 (12.0%) | 11 (9.9%) | 8 (16.0%) | 3 (42.9%) | 5 (31.2%) | ||

| Companies or organizations | 6 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (6.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (12.5%) | ||

| Conferences, seminars, workshops, or symposiums | 14 (13.0%) | 47 (42.3%) | 11 (22.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Others | 24 (22.2%) | 5 (4.5%) | 11 (22.0%) | 1 (14.3%) | 3 (18.8%) | ||

| The period of using EL as an instructional platform | Approximately six months | 37 (34.3%) | 19 (17.1%) | 17 (34.0%) | 3 (42.9%) | 6 (37.5%) | χ2 (12) = 24.509, p = 0.017 |

| Approximately one year | 28 (25.9%) | 23 (20.7%) | 5 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (25.0%) | ||

| Approximately two years | 11 (10.2%) | 30 (27.0%) | 11 (22.0%) | 2 (28.6%) | 1 (6.2%) | ||

| Until now | 32 (29.6%) | 39 (35.1%) | 17 (34.0%) | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (31.2%) | ||

| Classification Features | Total Sample | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| n = 430 | (%) | |

| Poor | 11 | (2.6%) |

| Insufficient | 24 | (5.6%) |

| Moderate | 113 | (26.3%) |

| Sufficient | 164 | (38.1%) |

| Exceptional | 118 | (27.4%) |

| To What Extent Do You Agree to Substitute Traditional Classes with EL Classes? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Slightly Efficient | Slightly Efficient | Somewhat Efficient | Very Efficient | Extremely Efficient | Statistical Models | |

| 141 (32.8%) | 97 (22.6%) | 145 (33.7%) | 39 (9.1%) | 8 (1.9%) | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 74 (31.5%) | 50 (21.3%) | 85 (36.2%) | 22 (9.4%) | 4 (1.7%) | p = 0.000 a |

| Female | 67 (34.4%) | 47 (24.1%) | 60 (30.8%) | 17 (8.7%) | 4 (2.1%) | |

| Age Group | ||||||

| 12–17 years old | 6 (60.0%) | 3 (30.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | p = 0.048 b |

| 18–24 years old | 74 (41.6%) | 32 (18.0%) | 45 (25.3%) | 21 (11.8%) | 6 (3.4%) | |

| 25–34 years old | 24 (26.4%) | 26 (28.6%) | 31 (34.1%) | 9 (9.9%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| 35–44 years old | 28 (23.9%) | 28 (23.9%) | 51 (43.6%) | 9 (7.7%) | 1 (0.9%) | |

| 45–54 years old | 9 (26.5%) | 8 (23.5%) | 17 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Degree of education | ||||||

| No schooling completed | 12 (41.4%) | 9 (31.0%) | 5 (17.2%) | 3 (10.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | p = 0.044 b |

| Primary (basic education) | 4 (57.1%) | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| High school, no diploma | 15 (48.4%) | 5 (16.1%) | 6 (19.4%) | 2 (6.5%) | 3 (9.7%) | |

| High school, diploma or the equivalent | 11 (42.3%) | 4 (15.4%) | 7 (26.9%) | 4 (15.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 69 (36.3%) | 42 (22.1%) | 56 (29.5%) | 19 (10.0%) | 4 (2.1%) | |

| Master’s degree | 19 (18.3%) | 26 (25.0%) | 49 (47.1%) | 9 (8.7%) | 1 (1.0%) | |

| Doctorate degree | 11 (25.6%) | 10 (23.3%) | 20 (46.5%) | 2 (4.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Unemployed | 3 (25.0%) | 2 (16.7%) | 4 (33.3%) | 3 (25.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | p = 0.038 b |

| Employed | 15 (20.3%) | 17 (23.0%) | 36 (48.6%) | 5 (6.8%) | 1 (1.4%) | |

| Student | 79 (44.6%) | 33 (18.6%) | 38 (21.5%) | 21 (11.9%) | 6 (3.4%) | |

| Teacher | 36 (25.5%) | 39 (27.7%) | 58 (41.1%) | 7 (5.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Other | 8 (30.8%) | 6 (23.1%) | 9 (34.6%) | 3 (11.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Classification Features | Total Sample | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Chat | 84 | (12.1%) |

| Discussion forums | 111 | (15.9%) |

| Feedback gathering | 55 | (7.9%) |

| Gamification (game principles) | 18 | (2.6%) |

| Grading system/assessment | 56 | (8.0%) |

| Others | 99 | (14.2%) |

| Training tracking | 34 | (4.9%) |

| Video conferencing | 132 | (18.9%) |

| reporting | 108 | (15.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasan, D.O.; Aladdin, A.M.; Amin, A.A.H.; Rashid, T.A.; Ali, Y.H.; Al-Bahri, M.; Majidpour, J.; Batrancea, I.; Masca, E.S. Perspectives on the Impact of E-Learning Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic—The Case of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054400

Hasan DO, Aladdin AM, Amin AAH, Rashid TA, Ali YH, Al-Bahri M, Majidpour J, Batrancea I, Masca ES. Perspectives on the Impact of E-Learning Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic—The Case of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054400

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasan, Dler O., Aso M. Aladdin, Azad Arif Hama Amin, Tarik A. Rashid, Yossra H. Ali, Mahmood Al-Bahri, Jafar Majidpour, Ioan Batrancea, and Ema Speranta Masca. 2023. "Perspectives on the Impact of E-Learning Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic—The Case of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054400

APA StyleHasan, D. O., Aladdin, A. M., Amin, A. A. H., Rashid, T. A., Ali, Y. H., Al-Bahri, M., Majidpour, J., Batrancea, I., & Masca, E. S. (2023). Perspectives on the Impact of E-Learning Pre- and Post-COVID-19 Pandemic—The Case of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Sustainability, 15(5), 4400. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054400