Communicating Moral Responsibility: Stakeholder Capitalism, Types, and Perceptions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Moral Responsibility (CMR)

2.2. Perceived Corporate Hypocrisy

2.3. Stakeholder Types and PCH

2.4. Stakeholder Capitalism Issues, CMR, and PCH

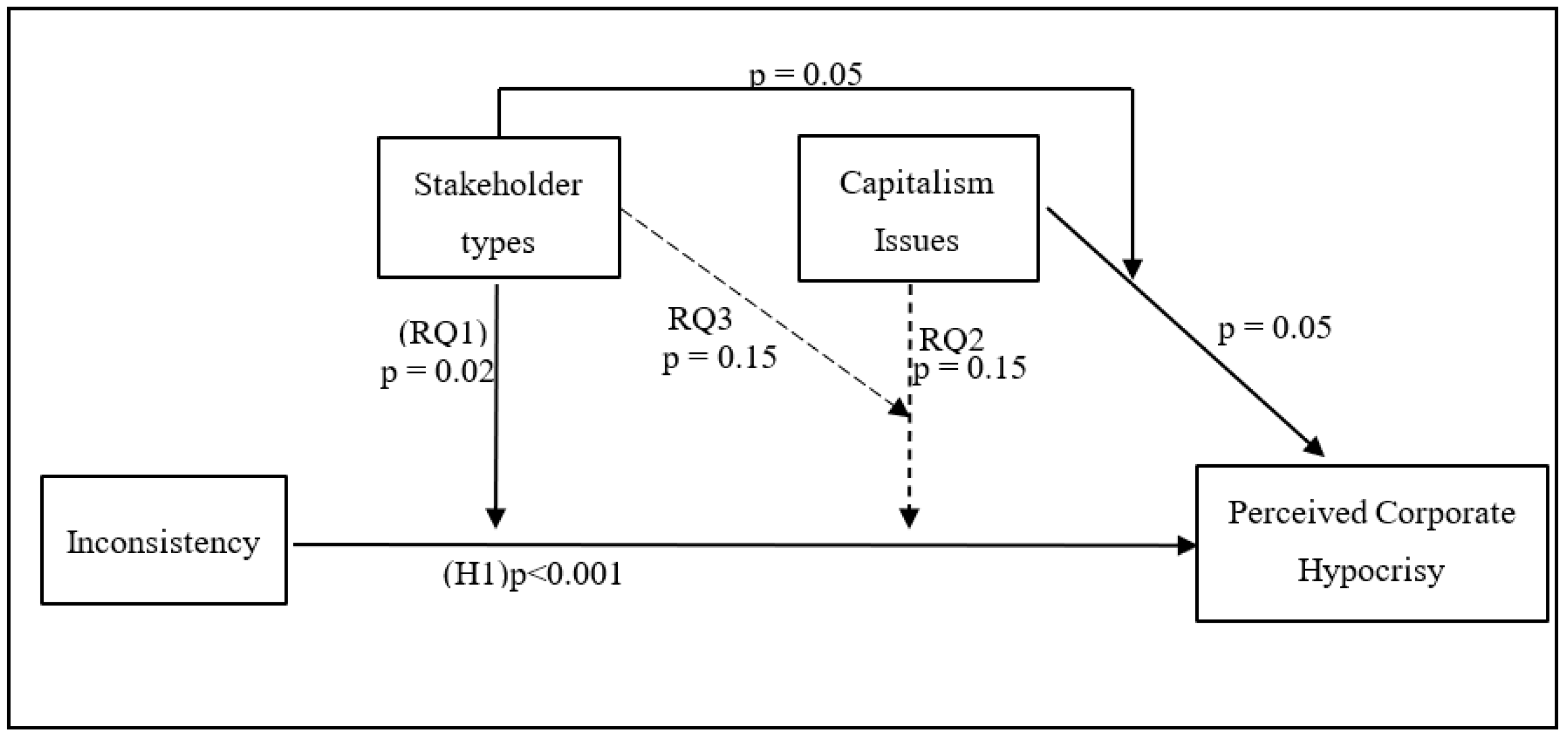

2.5. Stakeholder-Types Moderate Types of Stakeholder Capitalism Issues

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Stimuli

3.2.1. Developing Stimuli

3.2.2. Message Replication

3.2.3. Manipulation Check

3.3. Measures

3.4. Sample Selection, Procedure, and Data Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Respondent Profile

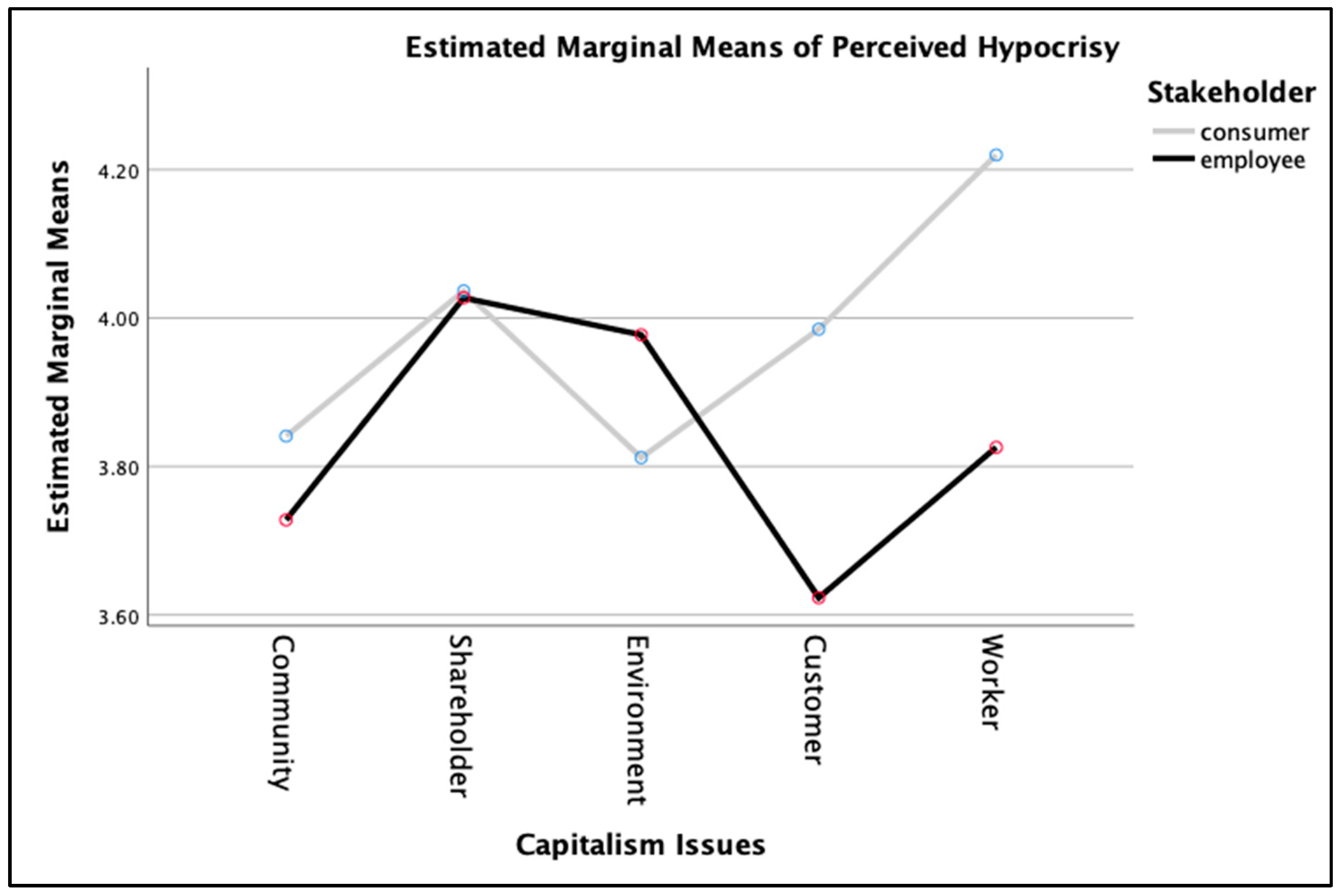

4.2. Hypotheses Tests

5. Discussion

5.1. Effect of Inconsistency on Internal and External Stakeholders’ PCH

5.2. Influence of Stakeholder Capitalism Issues

5.3. Types of Stakeholders Influencing Stakeholder Capitalism Issues’ Impact

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2020/01/05/why-stakeholder-capitalism-will-fail/#1e3c37a785a8 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Hess, K.M. “If You Tickle Us….”: How corporations can be moral agents without being persons. J. Value Inq. 2013, 47, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormio, S. Can corporations have (moral) responsibility regarding climate change mitigation? Ethics Policy Environ. 2017, 20, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/from-principle-to-practice-making-stakeholder-capitalism-work (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2019/08/19/why-maximizing-shareholder-value-is-finally-dying/?sh=1f9129ec6746 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Rhodes, C. Democratic business ethics: Volkswagen’s emissions scandal and the disruption of corporate sovereignty. Organ. Stud. 2016, 37, 1501–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/heatherfarmbrough/2018/04/14/hm-is-pushing-sustainability-hard-but-not-everyone-is-convinced/?sh=6ba667157ebd (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Coast Law Group. Available online: https://truthinadvertising.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Walker-v-Nestle-complaint.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- The Washington Post 2019. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/business/hershey-nestle-mars-chocolate-child-labor-west-africa/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Bhaduri, G.; Jung, S.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Effects of CSR messages on apparel consumers’ Word-of-Mouth: Perceived Corporate Hypocrisy as a Mediator. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2021, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.A.; Tao, W.; Ferguson, M.A. The joint effect of corporate social irresponsibility and social responsibility on consumer outcomes. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.W.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Consumer versus corporate moral responsibilities for creating a circular fashion: Virtue or accountability? Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2022, 40, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Korschun, D.; Troebs, C.C. Deconstructing corporate hypocrisy: A delineation of its behavioral, moral, and attributional facets. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Ha-Brookshire, J. Perfect or imperfect duties? Developing a moral responsibility framework for corporate sustainability from the consumer perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, N.; de Roeck, K.; Raineri, N. Hypocritical organizations: Implications for employee social responsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Ha-Brookshire, J.; Bonifay, W. Measuring perceived corporate hypocrisy: Scale development in the context of US retail employees. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Park, K.; Zhu, W. Linking CSR communication to corporate reputation: Understanding hypocrisy, employees’ social media engagement and CSR-related work engagement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderman, C.J.; van Hal, L.; Lambrechts, W.; Schijns, J. The impact of buying power on corporate sustainability-The mediating role of suppliers’ traceability data. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2021, 3, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JUST Capital. A Roadmap for Stakeholder Capitalism. 2019. Available online: https://justcapital.com/reports/roadmap-for-stakeholder-capitalism/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Schmeltz, L. Getting CSR communication fit: A study of strategically fitting cause, consumers and company in corporate CSR communication. Public Relat. Inq. 2017, 6, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Brookshire, J. Toward moral responsibility theories of corporate sustainability and sustainable supply chain. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werhane, P.H. Corporate social responsibility/corporate moral responsibility. In The Debate over Corporate Social Responsibility; May, S.K., Cheney, G., Roper, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 459–474. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/susanmcpherson/2019/01/14/corporate-responsibility-what-to-expect-in-2019/?sh=3f504cc3690f (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Fast Company 2019. Available online: https://www.fastcompany.com/90448178/does-capitalism-need-a-radical-redesign-to-become-more-inclusive?partner=rss&utm_source=rss&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=rss+fastcompany&utm_content=rss?cid=search (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Bhaduri, G.; Ha-Brookshire, J. The role of brand schemas, information transparency, and source of message on apparel brands’ social responsibility communication. J. Mark. Commun. 2017, 23, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Nielsen Company. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/04/Global20Sustainability20Report_October202015.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Markman, G.; Krause, D. Special topic forum on theory building surrounding sustainable supply chain management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanski, M.E.; Yammarino, F.J. Impact of behavioral integrity on follower job performance: A three-study examination. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 765–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, X.; Shi, L. Perception of corporate hypocrisy in China: The roles of corporate social responsibility implementation and communication. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hur, W.M.; Yeo, J. Corporate brand trust as a mediator in the relationship between consumer perception of CSR, corporate hypocrisy, and corporate reputation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3683–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.P.; Hu, H.H.; Lin, C.M. Consistency or hypocrisy? The impact of internal corporate social responsibility on employee behavior: A moderated mediation model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Zhou, J. Corporate hypocrisy and counterproductive work behavior: A moderated mediation model of organizational identification and perceived importance of CSR. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidler, S.; Edinger-Schons, L.M.; Spanjol, J.; Wieseke, J. Scrooge posing as Mother Teresa: How hypocritical social responsibility strategies hurt employees and firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Exploring US retail employees’ experiences of corporate hypocrisy. Organ. Manag. J. 2016, 13, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L. Effects of companies’ responses to consumer criticism in social media. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2013, 17, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Martin, K.; Parmar, B. Stakeholder capitalism. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Roundtable. Available online: https://opportunity.businessroundtable.org/ourcommitment/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- World Economic Forum 2019. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/12/why-we-need-the-davos-manifesto-for-better-kind-of-capitalism/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- World Economic Forum 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/mariana-mazzucato-covid19-stakeholder-capitalism/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- JUST Capital. Available online: https://justcapital.com/issues/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinstoller/2021/05/20/employees-are-more-vital-to-a-companys-success-than-shareholders-new-survey-finds/?sh=7260da3a24d0 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/maggiemcgrath/2019/11/12/bottom-of-the-barrel-92-of-americas-worst-corporate-citizens-in-2019/?sh=59f35f7f6fa1 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Small Business Chronicle. Available online: https://smallbusiness.chron.com/3p-triple-bottom-line-company-4141.html (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Mahmud, A.; Ding, D.; Hasan, M.M. Corporate social responsibility: Business responses to coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 2158244020988710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Business of Society. Available online: http://www.bos-cbscsr.dk/2019/09/25/business-purpose-big-trouble-but-wait-here-is-one-surprising-point-of-agreement (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Bebchuk, L.A.; Tallarita, R. The Illusory Promise of Stakeholder Governance. Soc. Sci. Res. Net. Elect. J. 2020, 106, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/annaschaverien/2018/12/12/consumers-do-care-about-retailers-ethics-and-brand-purpose-accenture-research-finds/#c2f694816f21 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Accenture. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/gb-en/insights/strategy/brand-purpose?c=strat_competitiveagilnovalue_10437228&n=mrl_1118 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Press, M.; Arnould, E.J. How does organizational identification form? A consumer behavior perspective. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 650–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Rapert, M.I.; Newman, C.L. Does perceived consumer fit matter in corporate social responsibility issues? J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoMonaco-Benzing, R.; Ha-Brookshire, J. Sustainability as social contract: Textile and apparel professionals’ value conflicts within the corporate moral responsibility spectrum. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/gregpetro/2022/03/11/consumers-demand-sustainable-products-and-shopping-formats/?sh=74b044776a06 (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Thorson, E.; Wicks, R.; Leshner, G. Experimental methodology in journalism and mass communication research. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 2012, 89, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Monthly Retail Trade and Food Services NAICS Codes, Titles, and Descriptions. Available online: https://www.census.gov (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Bhaduri, G.; Ha-Brookshire, J.E. Do Transparent Business Practices Pay? Exploration of Transparency and Consumer Purchase Intention. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2011, 29, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, M.; Kübler, D.; Steckel, J.C.; van Veldhuizen, R. Clean up your own mess: An experimental study of moral responsibility and efficiency. J. Public Econ. 2017, 155, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvino, J. Reframing “morality pays”: Toward a better answer to “why be moral?” in business. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patagonia. Available online: https://www.patagonia.ca/activism/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Times. Available online: https://time.com/collection/time100-companies/ (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Kaput, M.B. How Does Workplace Ethics Contribute to Your Success. Small Business Chronicles 2021. Available online: https://smallbusiness.chron.com/workplace-ethics-contribute-success-13871.html (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Bhaduri, G.; Ha-Brookshire, J. Gender Differences in Brand Information Processing and Transparency. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, M.D.; Brown, W.J.; Bocarnea, M.C. Differences in univariate values versus multivariate relationships: Findings from a study of Diana, Princess of Wales. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description of the Variable | Categories | Description of the Categories | Incorporated in the Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistency | Refers to whether corporate messages promising CMR, and their actions as portrayed by news reports are inconsistent or not. | Present | Corporate message endorsing CMR commitment but news report indicated that corporation failed to keep its CMR promises | Manipulated in stimuli |

| Absent | Corporate message endorsing CMR commitment and news report indicated that corporation kept its CMR promises | Manipulated in stimuli | ||

| Stakeholders | Two types of stakeholders for retail corporations: external and internal | External (retail consumers) | Retail consumers in the US | Controlled through quota sampling |

| Internal (retail employees) | Retail employees with at least one continuous year of employment at a US retail corporation | Controlled through quota sampling | ||

| Stakeholder Capitalism Issues | Issues corporations consider as the area of emphasis for their CMR. | Workers | Corporate and news message emphasized worker related CMR issues | Manipulated in stimuli |

| Environment | Corporate and news message emphasized environment related CMR issues | Manipulated in stimuli | ||

| Shareholders | Corporate and news message emphasized shareholder related CMR issues | Manipulated in stimuli | ||

| Customers | Corporate and news message emphasized customer related CMR issues | Manipulated in stimuli | ||

| Community | Corporate and news message emphasized community related CMR issues | Manipulated in stimuli |

| Variable | Levels | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–20 | 106 | 8.2 |

| 21–30 | 310 | 23.9 | |

| 31–40 | 301 | 23.2 | |

| 41–50 | 194 | 15.0 | |

| 51–60 | 162 | 15.5 | |

| 61 and over | 223 | 17.2 | |

| Gender | Male | 650 | 50.2 |

| Female | 646 | 49.8 | |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 725 | 55.9 |

| Hispanic | 238 | 18.4 | |

| African–American | 224 | 17.3 | |

| Asian | 66 | 5.1 | |

| Other | 43 | 3.3 | |

| Annual Household Income | Less than $20,000 | 220 | 17.0 |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 240 | 18.8 | |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 214 | 16.5 | |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 248 | 19.1 | |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 143 | 11.0 | |

| $100,000 or above | 228 | 17.6 | |

| Education | Some high school | 42 | 3.5 |

| High school degree | 281 | 21.7 | |

| Some college | 325 | 25.1 | |

| College degree | 358 | 27.6 | |

| Some graduate education | 48 | 3.7 | |

| Graduate degree | 233 | 18.0 | |

| Other | 6 | 0.5 | |

| Employment Status | Part–time employed (1–39 h per week) | 219 | 16.9 |

| Full–time employed (40 or more hours per week) | 602 | 46.5 | |

| Not employed | 263 | 20.3 | |

| Retired | 212 | 16.4 |

| Stakeholder Capitalism Issues | Stakeholder | Hypocrisy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ||

| Communities | Consumer | 3.84 | 1.65 |

| Employee | 3.79 | 1.59 | |

| Shareholders | Consumer | 4.06 | 1.33 |

| Employee | 4.06 | 1.41 | |

| Environment | Consumer | 3.81 | 1.51 |

| Employee | 3.98 | 1.39 | |

| Customers | Consumer | 3.99 | 1.64 |

| Employee | 3.62 | 1.52 | |

| Workers | Consumer | 4.20 | 1.67 |

| Employee | 3.83 | 1.57 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goswami, S.; Bhaduri, G. Communicating Moral Responsibility: Stakeholder Capitalism, Types, and Perceptions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054386

Goswami S, Bhaduri G. Communicating Moral Responsibility: Stakeholder Capitalism, Types, and Perceptions. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054386

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoswami, Saheli, and Gargi Bhaduri. 2023. "Communicating Moral Responsibility: Stakeholder Capitalism, Types, and Perceptions" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054386

APA StyleGoswami, S., & Bhaduri, G. (2023). Communicating Moral Responsibility: Stakeholder Capitalism, Types, and Perceptions. Sustainability, 15(5), 4386. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054386