Abstract

Addressing today’s most pressing challenges requires collaboration between professionals of different disciplines and the capacity to work effectively across sectors. Cross-sector partnerships (CSPs) are an increasingly common vehicle for doing so, but too often they fall short of achieving the desired social impact. Three years of research alongside a unique multi-sector partnership to prevent human trafficking identifies lack of shared understanding as the main problem, caused by conflict avoidance during early stages of partnership development. Counterintuitively, controversy is necessary to develop shared norms, power structure, and communication practices—all elements of participatory design—through a process of stakeholder dialogue. Effective dialogue requires people to explore, confront, and contest diverse perspectives; however, research finds that groups are more likely to avoid conflict and engage in consensus-confirming discussions, thereby undermining their effectiveness. Using the singular case study of a cross-sector partnership that formed to enact new anti-trafficking legislation, this study examines how conflict avoidance constrained the performance and sustainability of a cross-sector, multi-actor collaboration. The study finds that conflict avoidance stifles shared understanding of governance, norms, and administrative practices, negatively impacting multiple processes that are important to sustainable collaborations. The conclusion drawn is that conflict management should receive greater attention in the study and practice of cross-sector partnerships.

1. Introduction

Confronting human trafficking represents one of the most pressing challenges of the 21st century. The United Nations estimates that 21 million people, including some 5.5 million children, are victims of human trafficking worldwide [1], making it the second largest criminal economy in the world after drug trafficking. Human trafficking is fundamentally rooted in social and economic vulnerabilities caused by the wealth gap between rich and poor, the high value placed on material ownership and consumption as sources of self-worth and social status, and gendered low-wage work in both poor and industrial countries [2]. These structural elements are exacerbated by more dynamic variables—climate change and armed conflict, both of which have contributed to the worst migration crisis since World War II [3]. These factors (among others) combine to create marginalized groups of people who are highly vulnerable to other groups seeking to profit from their exploitation. The global reach of trafficking markets is a reminder of the shared vulnerability of people no matter here they live, and the need for countries to pursue cross-sector, multi-stakeholder collaboration for planning, testing, and coordinating trafficking prevention responses.

One trend holding the greatest potential for building the resilience of trafficking prevention efforts involves complex partnership projects [4] that buffer regional communities from vulnerabilities to trafficking. Collaborative efforts are necessary for a wide range of contemporary social projects in part because of the inability of governments to handle complex problems alone, and in part because more societal problems have become “wicked problems” that require the attention, commitment, and coordination of many interdependent players to find solutions [5]. Wicked problems are complex socio-cultural dilemmas, each one a symptom of another problem, which involve many different stakeholder groups with strongly held and conflicting beliefs about what ‘the problem’ is, and each of whom controls resources that are critical to positive progress. Collaboration between organizations and/or stakeholders has therefore grown in practice over the past three decades [6,7].

Collaboration for sustainability is recognized “as a key element to solve complex sustainability problems and as one of the principles of a sustainable organisation” [8] (p. 1). Accompanied by intense research interest from several fields, the focus has shifted from organizational sustainability to inter-organizational sustainability through collaborative arrangements (partnerships, coalitions, collectives, temporary organizations). Such arrangements can be effective in achieving trafficking prevention outcomes [4,7]. Yet many such partnerships struggle to meet their goals. Although they reside in different literatures, the barriers to healthy collaborations show a great deal of commonality: divergent partner priorities [6], staff or leadership turnover and funding constraints [7], lack of trust [6], lack of data sharing [8], lack of shared leadership [9], lack of guidelines and procedures for coordinated actions [9], differences in organizational culture, funding constraints, and member diversity [10,11].

These challenges are also characteristic of wicked problems, of which human trafficking is one [12]. Wicked problems produce a work environment characterized by uncertainty and complexity into which each partner comes from a different professional and cultural background, with conflicting or incompatible values [13], divergent knowledge perspectives, and differences in power [14]. The universe of actors is extremely diverse, their approaches differing widely depending on their profession, organizational mission, and identity. In the language of institutional theorists, different professional communities operate according to logics that contain conflicting or incompatible “expectations for social relations and human and organizational behavior” [15] (p. 104). They have unique vocabularies and perspectives about human trafficking—in addition to preconceived perceptions of each other. As a result, anti-trafficking initiatives are usually organized by discrete, highly specialized professional communities such as law enforcement, victim advocates, and policymakers ‘all operating in their own siloes’ [16].

Designing multi-faceted programs and interventions to human trafficking and other complex problems requires bridging these siloes to create “integrated, holistic and coherent policy-making where decision-making, implementation and monitoring involves actors from the public and private sector as well as civil society” [17]. Initiatives that bridge siloes effectively are not owned or led by any one person or entity; instead, they have a collaborative governance arrangement of equity among partners, and participatory decision making [18]. However, collaborative governance is most effective in cases when sectoral logics are transformed into a shared understanding of the causes, solutions, and goals of the issue at hand [19].

Conflict is a little-discussed requirement for achieving shared understanding. Group members must engage in constructive conflict to identify and discuss incompatible differences until convergence and consensus are reached. Yet there is a strong tendency towards conflict avoidance in workplaces [20]. Conflict avoidance is a strategy of conflict resolution. People tend to choose avoidance over confrontation in situations of low trust and power asymmetry, both of which are present in newly formed partnerships. Paradoxically, overt controversy is required in order to develop the shared understanding by which collaboration flourishes. Therefore, conflict avoidance undermines the efficacy of cross-sector partnerships to create and sustain the impact they seek.

This article focuses on a specific set of interdependent challenges that affect inter-organizational sustainability: achieving shared understanding between diverse parties, the role of conflict in doing so, and a strong tendency towards conflict avoidance in cross-sector partnerships (CSPs). (The term CSP will be used interchangeably in this article with “partnership” and “complex partnership”.) The key research goal is to explore the instances, motivations, and dynamics of conflict avoidance in a complex CSP, and trace the impact of conflict and conflict avoidance on its functioning and performance. Among the fields that study it, conflict is understood as ubiquitous and therefore necessary to manage head on. In this article, it is argued that understanding how to engage in conflict is a critical capability for collaboration.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Complex Networked Partnerships–Dynamics and Challenges

Complex partnership projects that combine public, private, and voluntary sectors have risen in number and influence over the last three decades [21] in response to a class of (wicked) social problems that governments are not able or willing to regulate [22] or that no single entity is singularly “responsible” for handling. Human trafficking is one of those problems. Confronting human trafficking is a complex project for which classic forms of hierarchical, centralized, or top-down governance are not effective. Each sector has something vitally important to contribute, but no one can force their cooperation. They each have relatively equal power vis-à-vis one another, and no one organization or sector has ultimate responsibility for coordinating anti-trafficking efforts. Because they are non-hierarchical, coordinated action takes place under the protocols of collaborative governance, a “collective decision-making process that is formal, consensus-oriented, and deliberative” wherein “participants engage directly in decision making” [23].

For these reasons, CSPs are unlike other workplaces. They have a flat organizational structure in which there are few or no levels of middle management. Well-intentioned collaborators encounter each other in a highly challenging work environment characterized by knowledge uncertainty and dynamic complexity [24], in which work is carried out by individuals from diverse professional and cultural backgrounds. As a result, partners “might be using the same words for different concepts or different words for the same concepts without noticing (or) might be unaware of unshared individual knowledge which could be crucial for completing the task successfully” [25]. Work is also “distributed” which refers to nature of “teams whose members use some form of digital communication technology as part of their work across locational, temporal, and relational boundaries to accomplish an interdependent task” [26] (p. 782). In distributed workplaces, tasks are carried out by autonomous and highly specialized teams and subgroups who are spatially and temporally distant from each other, many of whom have not worked together before and have differing levels of technological expertise [27].

This kind of diversity is understood as a necessary and desirable characteristic of complex collaborative projects. Systems theorists have long held that diversity is a characteristic of complex adaptive systems. For example, species diversity makes ecosystems more resilient, and diverse sources of distributed energy (solar, wind) makes an electrical grid more resilient. Theoretically, mind (cognitive) diversity is just as central to collaboration [28,29]. According to Ashby’s (1960) law of requisite variety, “collaboration functions to marshal and deploy a group’s diversity of available socio-ecological resources to meet the complexity of the problem environment they encounter” [30] (p. 121). Diverse teams are also more creative [31], make better decisions [32], and outperform homogenous groups [33]. However, diversity also makes it more difficult to achieve shared understanding [34] which constitutes a key condition under which inter-organizational cooperation emerges [35].

2.2. Shared Understanding

CSPs cannot operate without shared understanding. Prior research has established that shared norms contribute to the sustainability of a partnership [36], along with common goals [37], shared technical knowledge [38], shared understanding of time [39], a shared understanding of the objectives, achievable project goals, and detailed strategic plan [40]. A recently developed framework for considering these variables together was introduced in 2022 by Weber and colleagues [19]. The authors reviewed the literature on cross-sector partnerships and identified five conditions of congruence that lead to sustainable cross-sector collaboration: congruence of goals, governance structures, administrative processes, accountability processes, and exchange modalities. Summarizing extant literature, the authors write that congruence about mission and goals is a pre-condition to sustainable CSPs, and posit that congruence is especially important in reference to governance structures, administrative processes, and accountability. These structures and processes must be created in new cross-sector collaborations. Initially, each partner brings their own understanding and preferences to the table; however, divergent personal views can and do converge as people “integrate concepts gleaned from one another and/or develop new, shared concepts” [41] (p. 577).

The process by which “personal views on a problem converge into a shared understanding of a problem” [41] (p. 577) is called social learning. Social learning can shape individual viewpoints to align with the views of a collective [42], change the range of considerations influencing a person’s values [43], and form new values and preferences where previously absent [44]. Social learning develops through participatory methods and social interaction involving deliberative dialogue during which people explore, confront, and contest diverse perspectives [45]. As use of the word “contest” suggests, overt controversy is inherent in social learning. Group members not only need to hear each other’s different perspectives, but to focus on and evaluate each viewpoint inconsistent with one’s own perspective. Only through the process of constructive conflict can social learning succeed in generating shared understanding.

2.3. Conflict and Social Learning

Despite research which underscores “the difficulty of leveraging the diverse knowledge and skills of members from different industry sectors” [46] (p. 196) comparatively few studies directly address the role of conflict in doing so [47,48]. Extant research has framed conflict as a condition standing in the way of partnership and studied its causal conditions including power asymmetry [49], communication breakdowns [50], governance capability [51], and methods of conflict resolution such as mediation or negotiation [52]. Many studies of CSPs depart from a theoretical framework that focuses on “dynamics in the institutional field that shapes the context in which partnerships unfold” [49] (p. 1) rather than focusing on interpersonal dynamics that can shape and transform institutional fields themselves. In 2021, Vogel and colleagues argued that microlevel interactions “where the involved partners enact different sectoral scripts and resolve emergent tensions and conflicts, still awaits further exploration” [53]. As described above, one such microlevel interaction is overt conflict to move from individual perspectives to one shared understanding. Observed by Ostrom in research on governance of the commons, “getting the institutions right is a difficult, time-consuming, conflict-ridden process” [54].

The word “conflict” tends to be associated with stress, anxiety, worry, and fear. It conjures images of arguments, fights, even armed conflict. Its academic definition is more helpful. Conflict is defined as perceived incompatible goals and actions between interdependent parties [55,56]. Incompatibility of goals relates to the conflict of interests that causes disagreement between the parties. Underneath goals are varying interests, perceptions, and belief systems. A core tenant among scholars of conflict resolution is that goals can align if differences at these deeper cognitive levels are surfaced, discussed, examined, and ultimately reconciled through deliberative dialogue. Thus, the importance of conflict for social learning is its effect on conceptual change; that is, changes to an existing belief, idea, or worldview.

All individuals develop worldviews—theories of how the world works—which underlie their perceptions of reality and are highly resistant to change. Worldviews are mental models, internal conceptions, and representations of the outside world (historical, existing, or projected) [57]. In the face of new or conflicting knowledge, individuals are more likely to enrich and modify their existing worldviews than change them [58]. Psychologists call this the “confirmation bias", which is the tendency to interpret new information in line with (as confirmation of) our pre-existing belief system. Yet mental models must change for convergence to occur. Research suggests that conflict interrupts the confirmation bias through debate and argumentation. Exchanging arguments catalyzes conceptual change “in part owing to the cognitive elaboration demands that argumentation requires” [59].

This may explain why studies have found that argumentation—“direct, repeated exchanges” about diverse participants’ worldviews held greater potential for individual-level convergence over “more harmonious” dialogue [60]. Constructive conflict effects deep or ‘radical’ conceptual change “in which grounded conceptual models collapse and are replaced by new ones” [61]. In sum, research suggests that argumentation—a repeated process of negotiation, discussion, and debate over issues in contention—is required to reach shared understanding through the social learning process [62]. Hard conversations, constructive self-assertion, asking and answering challenging questions, and expressing honest disagreements are part and parcel of effective communication across boundaries [63], at least in the Western context.

The necessity for overt controversy in the partnership lifecycle is not a new idea. One of the earliest models of collaboration, and the necessity of conflict within it, was developed by education researcher Bruce Tuckman in 1965. Tuckman’s model of group development [64] identifies a four-stage development process that teams go through in order to work effectively: forming, storming, norming, and performing. Forming is the earliest stage of team building. Groups meet to discuss and agree on goals, and then get busy on tasks. This stage transitions into the next one, storming, in which competing ideas are introduced and members confront each other’s ideas and perspectives. Storming is a phase of overt conflict. Social learning in this stage generates shared understandings among participants, and this enables them to move into a norming stage in which the goal is reconstructed and agreed upon, then developed into a mutual plan and metrics for performing.

Tuckman’s insight that conflict is required for effective groups is critical; however, he did not elaborate on the difficulty of working successfully through this stage. Other scholars have addressed how collaborators move through the process of developing collaborative governance together, and agree that it is a staged process of deliberative dialogue. A recent model by Elron and Vigoda (2017) proposes that shared understanding develops through three stages of social learning [65]. The first stage of Construction refers to a group conversation in which each member describes “the problem” and how to deal with it, while the other partners are actively listening in order to understand the member’s perspective. The second phase, Co-Construction, is a sensemaking process [66] in which group members clarify, elaborate, and build on each other’s views and perspectives. Both stages build the social capital (trust) and relationships needed to navigate constructive conflict, the stage in which controversies emerge and are embraced. Constructive Conflict involves identifying and discussing conflicting differences until group members mutually agree on one shared understanding.

Specifically, effective teams need to engage in a type of conflict called task conflict, “a perception of disagreements among group members about the content of their decisions and involves differences in viewpoints, ideas, and opinions” [67] (p. 102). Task conflict is healthy for groups, and beneficial in two ways. “Groups that experience task conflict tend to make better decisions because task conflict encourages greater cognitive understanding of the issue being discussed” [68] (p. 742). This effect holds at both the individual level [69] and the group level [70]. A second beneficial effect of task conflict is greater satisfaction with group decisions and a desire to stay in the group [71]. Strong commitment to a partnership is one of the most important indicators of sustainable participation.

While there is a dearth of literature directly addressing conflict in complex partnerships, some evidence exists that many cross-sector partnerships avoid conflict. One study of 30 partnerships applied Tuckman’s analytical model and found that the majority had skipped storming and norming phases, going directly from forming to performing [72]. The partnerships that did not skip storming were found to perform better and sooner than their counterparts. Since storming is a stage during which controversies and differences are surfaced, this skipping pattern appears to be the result of conflict avoidance. Conflict avoidance is a strategy of conflict resolution, motivated by self-protection, relationship protection, and conflict circumvention [73]. An early assumption in the study of conflict behavior was that avoidance represented a passive strategy, resulting from low concern for oneself and other. This understanding of avoidance was not accurate, and research has provided a more complete picture about what motivates avoidance, and different types of avoidance strategies [74,75,76].

One form of avoidance, topic avoidance, has been well-researched. Topic avoidance refers to the withdrawal of information as when people suppress arguments or avoid discussing certain issues. Prior research has found that people withhold information to prevent harm to the relationship or to guard against the distress of a relational partner [77,78]. Trust and power also influence the motivation to practice avoidance. High-trust situations negatively influence conflict avoidance; conversely, a low level of trust heightens the likelihood that avoidance will be used as a coping strategy [79]. Since trust tends to be low at the outset of complex partnerships, the use of conflict avoidance is a common initial strategy for processing the complexity created when a multiplicity of logics meets [80,81]. A person’s relative power in a relationship also influences willingness to disagree with one another. Typically, people prefer not to dispute with a person in authority [82,83,84,85]. However, when parties of perceived equal power trust each other, they are more likely to choose more cooperative negotiation strategies to resolve their differences and less likely to use avoidance as a strategy [86]. It is for these reasons that collaborative governance is essential to high-performing collaboratives, with its emphasis on equity among partners particularly important. Shared leadership is a core requisite of collaborative governance.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the context and emergence of a complex, inter-organizational and cross-sector partnership that was formed to enact new anti-trafficking legislation in a region of the United States. Section 3 describes the methods used to gather, assess, and interpret data. Section 4 contains findings highlighting the impact of conflict avoidance on shared understanding, and subsequent effects on project implementation. Section 5 reflects on the findings within the broader context of collaborative social projects, and discusses limitations of the study.

3. Partnering to Prevent Human Trafficking

Human trafficking education is a preventive intervention strategy that is almost revolutionary in the United States, where human trafficking is understood as a crime and approached primarily through a criminal justice lens. Prevention stresses addressing root causes, preventing harm before it occurs (known as primary prevention), and addressing both supply and demand dynamics using coordinated, integrated approaches. Education is widely seen as a sustainable, long-term investment in human trafficking prevention [87,88,89,90] because students are one of the most at-risk populations for victimization, and K–12 school campuses have become active recruiting grounds for traffickers [91].

California was the first state in United States to require human trafficking prevention through education. California Assembly Bill (AB) 1257, the Human Trafficking Prevention Education and Training Act (HT-PETA) was the first piece of legislation passed in the U.S. to mandate anti-trafficking education as a primary vehicle for reducing the vulnerability of children to human trafficking. The mandated education and training included information for teachers and other school staff to recognize the signs of human trafficking [92] and information for students on “the prevalence, nature, and strategies to reduce the risk of human trafficking, techniques to set healthy boundaries and how to safely seek assistance; and how social media and mobile device applications are used for human trafficking” [93].

While the legislation was laudable, California legislators passed HT-PETA without appropriating any state funds for school districts (e.g., to pay for teacher training) and without a compliance measurement system stipulated in the statute. Thus, the responsibility fell wholly to school districts to pass their own human trafficking education policies, adopt their own implementation efforts and compliance metrics—all while working from within their own existing budgets [94]. The average income of residents varies widely between districts, affecting the size of tax revenue streams. Since some districts have large budgets while others have while others do not, the risk of uneven implementation was high. Specifically, schools in low-income districts have fewer resources to pay for teacher training even though children living in low-income communities are at a higher risk for being trafficked. Since implementation of AB 1257 depended on a district’s revenue stream, children and teachers who need anti-trafficking education the most were less likely to receive it. This was the context within which the Collective for Trafficking Education and Awareness (hereafter CSEA or “the Collective”) formed.

3.1. The Collective to Stop Exploitation through Awareness (CSEA)

Many CSPs form in response to an issue or problem requiring social change. The Collective for Trafficking Education and Awareness aimed to develop a comprehensive human trafficking curriculum for teachers and students. CSEA came together between 2016 and 2017, evolving in 2018 into a high-diversity CSP between the voluntary sector (three nonprofits of different sizes and organizational scale), the public sector (the County district attorney), the private sector (a finance and wealth management firm), the so-called “fourth sector” of for-benefit enterprises and philanthropists (individual donors) and, perhaps most remarkably, an international development donor, the Akra Foundation. (Names of participating organizations have been changed to protect privacy.)

3.2. Composition and Structure

Initially, the Collective consisted of four individuals, each representing a different organization (see Table 1 below): the district attorney herself, the President of Educate to Prevent Trafficking (EPT), a Senior Program Director at Coalition to End Exploitation (CEE), and the Director of Justice & Advocacy Institute (JAI). Each NGO had anti-trafficking curriculums and had previously been competing for grant money from the county to implement them. The goal of the collaboration was to end the competition between them and develop a multistage educational program that incorporated all three. EPT had the curriculum with the greatest level of scaling capacity: it was an online interactive training for teachers who, after completing the training, then received lesson plans with teaching content, and individualized support for integrating the training into their courses. JAI had an innovative training that involved participatory theatre, and which was designed to engage an entire student body at one time. CEE’s curriculum was an after-school mentoring program for at-risk youth. When integrated, the Collective’s program provided a skills-based, multifaceted curriculum with the goal of helping teachers and schools increase youth safety, prevent the recruitment of children by individual traffickers, and address the root causes of vulnerability linked to victimization.

Table 1.

Partners within CSEA.

This small group worked through the details of the new combined curriculum together for a year. The passage of AB 1257 in 2017 further catalyzed the momentum of the project, and its goal of providing comprehensive anti-trafficking education.

Also in 2017, the director of a major finance management firm (WMF) became involved. Introduced to the nascent Collective by a client, WMF’s director offered to help with funding. They facilitated a private sector network of two dozen local philanthropists to invest in the plan, and negotiated an agreement with the firm’s philanthropic foundation (Akra Foundation) to co-invest a percentage of each client’s contribution. The donor network raised the several million needed to fund the project over a multi-year period. The Akra Foundation provided a structure for developing a project contract, including detailed measurement and evaluation of impact metrics. To the author’s knowledge, Akra’s investment was first time an international development donor based outside the United States has funded a large development project within the United States.

CEE was an international development organization itself, and the largest of the three NGOs, so Akra Foundation funded the project contract to them, while EPT and JAI were situated as subcontractors. Together with the district attorney’s office, they formed the Team for Operational Progress Support or TOPS. TOPS was the operational and implementing arm of the Collective, responsible for project implementation. TOPS’ implementation model involved several steps. First, they contacted school district leaders for permission to introduce EPT’s teacher training and JAI’s student training. Once permission was received, TOP engaged in outreach to teachers, counselors, and nurses in order to train them. Once these staff were trained, JAI’s student training could commence. Situating EPT’s training as a prerequisite to JAI’s training was a necessary step because trafficking victims often self-disclosed at JAI’s training, and the teachers on hand needed to know how to handle these situations when they arose. CEE’s afterschool training came after EPT’s teacher training for the same reason.

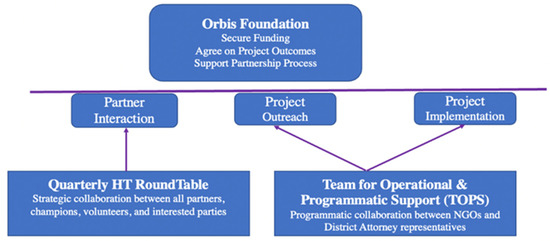

WMF did not participate in TOPS (for reasons discussed further on), instead hosting a different meeting called the Quarterly Human Trafficking Roundtable (hereafter the Roundtable). The Roundtable was a bridging space between the Collective participants, donors to the project who wanted to be more involved, and the peripheral community of “champions”, volunteers, and other parties. As is common in complex partnerships, a plethora of interested organizations offered to volunteer themselves for various tasks (e.g., graphic design, developing social media content) in a broad show of support and interest, and participated in the Roundtable to stay connected. The membership of this quarterly meeting changed over time, but usually included the District Attorney, Akra’s Director, and the heads of all the NGOs, along with the staffing members of TOPS. The Roundtable was the only space within which private sector participants (WMF and individual donors) were able to participate. Akra participated in both spaces, once monthly in TOPS and quarterly at the Roundtable. The structure of the Collective is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Basic Structure of CSEA.

4. Methods

4.1. Case Study Approach

The research presented here was gathered over three years, through a learning partnership and action research process developed in collaboration with CSEA partners. The singular study of CSEA is called a case study. Perhaps the most prominent advocate of case study research, Robert Yin defines it as “an empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident” [95] (p. 14). Yin’s definition articulates two principles important to this investigation. First, case studies are intended to document people’s perceptions of key events, situational dynamics, and lived experiences using ethnography as a guiding method. Especially because CSEA is a somewhat unique inter-organizational form, the approach was guided by the general principle that the Collective’s creators and members had the greatest insights into the research topics and their perspectives should be taken seriously.

Second, Yin’s definition is forgiving regarding more traditional notions of spatial and temporal ‘boundedness’ that should define the unit of analysis. For example, Gerring describes “an intensive study of a single unit…a spatially bounded phenomenon—e.g. a nation-state, revolution, political party, election, or person—observed at a single point in time or over some delimited period of time” [96] (p. 342). CSEA is a distributed network with fuzzy boundaries, consistent with how other complex collaboratives are structured. Its complexity makes it well suited to the case study approach.

Within the case study approach, this study is also a form of multilevel research because it studies behavior at the individual, group and organizational level. Multi-level research is a methodological approach for studying phenomenon, such as social networks, that involve multiple levels of social interaction (i.e., individual perceptions, group-level behavior, organizational learning, and social change). Multi-level research on networks is surprisingly scarce [97] despite strong advocacy from within the evaluation literature which stresses the particular importance of multi-level research when studying inter-organizational networks [98]. My rationale was that the complex nature of the Collective required a research design able to inquire—and integrate findings about—individual-level perceptions (beliefs, competencies, and actions), small group dynamics (group learning, intergroup communication, and conflict), and the role of intergroup and inter-organizational relations on overall CSP sustainability. The approach in doing so is called participatory action research (PAR).

4.2. Participatory Action Research

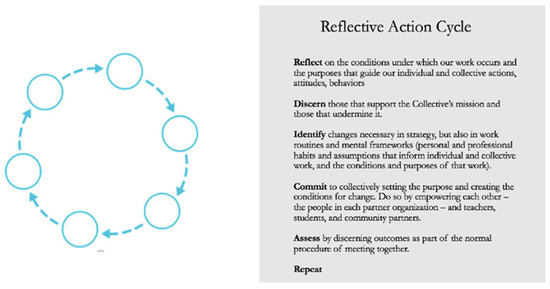

Participatory action research (PAR) is a method within a structured and systematic process for continually improving decisions, modes of governance, management policy and practices by studying and learning from the outcomes of decisions previously taken. It is an iterative process in which practitioners test hypotheses and adjust behavior, decisions, and actions based on what they learn. Action research facilitates social learning by involving participants as co-researchers who can steer inquiry, test ideas, gain new knowledge, ask questions, and engage in collective decision making. Figure 2 models the basic process used in this study, the Reflective Action Cycle. Together, lead researcher and co-researchers gather and analyze information in a continuous or ‘spiral’ process of learning and reflection. The role of the lead researcher is to be a good learning partner, engaging members in a facilitated, participatory process of inquiry to gain a deeper understanding of their needs and talents, co-design areas for growth that build on this knowledge, communicate findings back to the Collective as discoveries are made, and (importantly) engage co-researchers in the process of interpreting the findings.

Figure 2.

Reflective Action Cycle.

4.3. Data Collection

Triangulating data source and type is a requisite for rigorous case study research. Data was collected in four main ways: observation, participant observation, interviews, and survey research. Quiet observation of group meetings, and initial open-ended interviews with CSEA members were designed for Reflecting on the condition and purposes of the Collective at that time. After two months, I transitioned from observation to participant observation in team meetings. My participation increased joint understanding of CSEA’s condition and purposes at that time and Discerning areas for positive change. Identifying happened in small group meetings and one-on-one conversations in which I employed a technique called in-depth interviewing (IDI) to collect personal histories, perspectives, and experiences in the Collective to date. In-depth interviewing is used to achieve a holistic understanding of the interviewee’s point of view or situation enabling “a mutual exploration of the meanings the interviewee applies to their social world” [99] (p. 99). Committing involved taking an action or decision based on new data generated in previous stages. Assessing involved creating room/time in regular internal meetings to follow up on these actions, reflect on their success or need for revision, and plan experimentation.

The fourth source of data collection was an online survey designed to reveal perceptions about indicators of collaborative capacity and multi-level learning [100,101]. This survey was a small-n tool, with a participating group between 10 and 12 people. It was not designed to look for statistically significant effects, but to (a) gather perceptions and insights of people designing a truly novel social change partnership, and (b) create a rough baseline for CSEA on indicators with something to say about inter-organizational network effectiveness. The surveys also provided some clues as to the measures that are likely to be most effective building collaborative capacity (see Table 2). Finally, they provided a mechanism for partners to assert agency over the research agenda. Following these trends over time allowed us to assess the effectiveness of actions and decisions. The survey was designed to explore goals, governance, administration, and accountability factors mentioned earlier, via the associated process variables under study.

Table 2.

Action Research Inquiries and Indicators of Collaborative Sustainability.

5. Findings

The action research approach proved effective in supporting change management, especially by TOPS whose members began basing new decisions on evidence and best practices associated with learning organizations. For example, the group was evolving towards a collaborative governance regime, but it had taken over a year to do so on their own (discussed below). When the action research process revealed the concept of collaborative governance, and the amount of time typically involved in building mutual trust and a sense of shared leadership, TOPS members came to understand that their first year of ‘rolling out the curriculum’ was actually a pilot year. Proposed as an action research question, the idea of a pilot or ‘start-up’ year gained traction and caught on as CSEA members continued learning about—and grappling with—the size and complexity of their endeavor. Ultimately, they changed their contract with Akra to restructure the first year of “Implementation” into a first “Pilot Year” of experimentation and learning, and added a fourth year to the project.

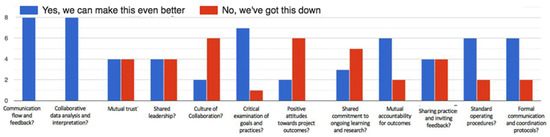

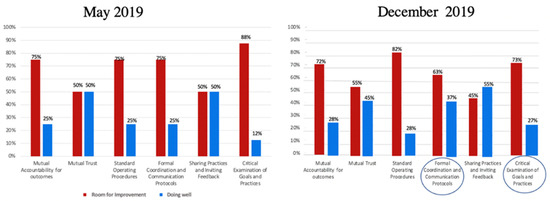

Action learning also assisted in TOPS’ development of an internal governance structure—which was not in place when the research began—and the appointment of a monitoring and evaluation lead to monitor CSEA’s progress and take over the action research. Specifically, TOPS members implemented important structural changes based on the results of the first action learning survey (ALS #1). TOPS convened a two-day summit that was structured around the results of ALS #1. A summit is a facilitated workshop that engages participants in order to make project decisions, create the project management team, and create project deliverables. As a result of basing the summit’s agenda on its own perceptions of problem areas, TOPS implemented the following important structural changes: they established and formalized their internal governance structure, devised a new system for coordinating outreach to school districts, and began formalizing communication protocols. ALS #2 documented a slight increase in confidence around formal communication and coordination protocols as these standard operating procedures began going into place (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Indicators of Collaborative Capacity.

ALS #2 also documented a slight increase in positive perceptions about critical examination of goals and practices (see Figure 4), perhaps because action research is designed to do precisely that, but it was a small change. In addition, although the following sections describe other instances of action learning leading to programmatic or structural changes, there was overall very little change over time on the majority of collaborative capacity indicators. In both surveys, members of CSEA consistently ranked themselves low on indicators of governance, shared goals, and administration, previously described (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Comparative Changes between Surveys.

ALS#2 also found that that most of CSEA’s members were conflict-averse. This was a large increase from ALS#1, on which most people opted to report that they were “Neutral” on the statement “Open conflict and disagreement is stressful”. ALS#2 removed the neutral option, which accounted for the increase in affirmative responses. In feedback to the Collective about ALS#2, the action researcher highlighted this finding and shared information about the necessity for constructive conflict in complex partnerships. This may have increased members’ anxiety about conflict and reinforced the use of topic avoidance to cope, because there was no political will to address this finding. In fact, there was a visible decline in the willingness to engage in Assessment about any of the findings from ALS#2. At the same time, tensions caused by suppressed conflicts grew larger until several members experienced an escalation of interpersonal conflict during a TOPS meeting.

The unintended escalation of relational conflict was unfortunate, and resulted in unconstructive conflict behavior between TOPS participants. However, its aftermath involved focused and facilitated problem solving in a demonstration of the positive effect of conflict on organizational change. TOPS members used the episode to address outstanding issues (as discussed below) that were impeding their work. Ultimately, the aftermath of this episode catalyzed two additional summits based on ALS#2. The first one focused on governance and the second one focused on monitoring and evaluation—both areas that CSEA had struggled to implement successfully.

The following subsections examine how unresolved conflict affected CSEA’s process of agreeing on goals, governance structures, and putting administrative structures into place—including accountability mechanisms. Instances of unaddressed conflict were connected to specific problems in each area including contested leadership, unaddressed controversy over project scope, differences in time urgency between partners, and a perceived power imbalance that undermined the collaborative governance structures that CSEA was trying to construct.

5.1. Goals

Agreement on a project’s goals is one of the earliest and most important outcomes of early partnership planning. Of these, agreement on scope is vital—including choosing shared metrics against which to measure progress. The earliest and most consequential instance of conflict avoidance involved changing the scope of the project, which reduced “the degree of similarity in performance goals among team members” [114] (p. 221). Prior to WMF becoming involved, the three NGOs and the DA had envisaged a project that would pilot their integrated curriculum in one school district, involving three to five schools. However, WMF and Akra Foundation suggested that the educational program should be designed to scale across all 43 school districts in the county. The expansion in scope extended the project’s reach to over 350,000 students and 700 schools, including charter schools, juvenile detention facilities, and alternative schools. This whole-of-system approach was proposed as a condition of donors’ involvement.

Clearly this was a tremendously large scope change, albeit a rational one from the private sector’s point of view. It was a proposal grounded in the institutional logic of the business sector. Since the 1960s, businesses and their managers have taken a systems approach to management that translates into a holistic approach to doing things and of seeing the world. For social impact investors moreover, the value of scaling up is inherent in their desire to create large-scale social change. Protecting children from sexual predation and labor exploitation is a project with urgency built into its very nature; each year that passes is a year that a child in school either receives protective education or does not.

WMF, the donors, and Akra partners felt optimistic and energized about ‘scaling up’. The nonprofit partners on the other hand harbored serious concerns that the county-wide approach was too big for the proposed three-year timeframe and their current level of staffing. Yet despite their level of worry, none of the three NGOs expressed their concerns. Even given the seniority of NGO leadership, “no one felt comfortable raising the issue with the private sector partners”. Interviews with the nonprofit partners indicated a reticence to raise the issue directly with WMF and the Akra Foundation “because they were the ones with the money. I think we all felt a little bit like we had to go along with it.”

This was the earliest instance of topic avoidance, seemingly motivated by a perceived power imbalance between the donor organizations and the implementing organizations. Because WMF’s donor network and Akra Foundation controlled the monetary resources, the nonprofits perceived that that the private sector partners had a greater level of power and influence in the Collective. The perceived power asymmetry weighed heavily in the NGOs’ decision to suppress discussion over scope concerns. EPT, CEE, and JAI felt that the new scope was not realistic, but avoided disagreeing with the proposed change out of a perception that they were lower-power actors. WMF’s director was unaware of the perceived power differential vis-à-vis the other project participants, and no one felt comfortable discussing it in what could have been a strategic conversation about shared leadership. The perceived power difference is antithetical to collaborative governance which, as discussed earlier, is based on equity among partners and decision making through deliberation and dialogue. Instead, as a direct result of conflict avoidance, WMF had a level of undue influence over project design.

Impact of Power Asymmetry on Stakeholder Engagement

An early outcome of WMF’s influence over project design concerned the question of who else the partnership should include. The best practices for choosing partners involve feasibility studies, stakeholder mapping, stakeholder interviews, and public forums [115]. These processes are necessary in order to identify relevant stakeholders, defined here as “individuals, groups, organisations and/or networks that have the power to influence a partnership and/or an interest in it” [116]. However, the time involved in these processes is off-putting to actors who are time-urgent. In this case study, time urgency was observed to be higher among the private sector partners and among individual donors (many of them current or former private sector leaders). Private sector actors have been found to experience a greater sense of time urgency than other sectors [117,118]. In this case, the expectations of the faster-paced private sector stakeholders influenced and accelerated the early planning phases of the project. The three NGOs described feeling rushed to complete the proposal for Akra. Perceiving that they lacked sufficient time, the three NGOs relied on the relationships that they already had with the education sector instead of cultivating new ones. This was a mistake because their existing relationships involved stakeholders at the wrong level—counties, instead of school districts.

Those individuals, groups, organisations and/or networks that have the power to influence

Counties are critical sites for regional coordination of educational entities and initiatives in California; so much so that California state law requires that each of California’s 58 counties has its own County Office of Education (COE). The original group of four had been working with the local COE since early days, and the COE was a big supporter of their project. However, school districts in California have more authority when it comes to curricular changes, such as the addition of the new proposed curriculum. Had CSEA used stakeholder mapping and/or landscape analysis, it is likely that they would have recognized this and chosen different representatives from the education sector as implementing partners. Instead, CSEA formed without talking to the local districts, or including their leadership in the project design.

This caused major implementation problems. CSEA members had assumed that schools would welcome the free, comprehensive anti-trafficking curriculum to help them comply with the new law, AB 1257. This turned out to be inaccurate for several reasons. First, creating demand for any product (e.g., the Collective curriculum) requires the target audience to perceive a need. However, awareness of “the problem” (the threat posed by traffickers) varied widely by district, and was low overall. Thus, political will to comply with the new law was low. Second, buy-in to any social change project is generally difficult to attain unless those who are most directly affected have been included in the design and development process [119]. CSEA had developed a solution for educators to adopt and had not expected they would need to convince educators, parents, and district leaders that their program was the best solution. Using the language of the private sector, many schools did not see the “value proposition” of the comprehensive curriculum as was expected. Ultimately, the implementation process was significantly slowed by the time it took to engage in personal outreach to each individual district seeking their permission to implement CSEA’s curriculum.

5.2. Governance

Governance structures evolve over time in CSPs; they take time to instantiate and cannot be imposed. However, the development of governance structures in CSEA was delayed by an unaddressed leadership conflict. Conflict over leadership was linked to a competitive dynamic that had emerged between JAI and EPT in the original group of four. As noted above, EPT had the most scalable program and the most comprehensive curriculum out of the three NGOs. However, since EPT was based outside the county of work, JAI had once suggested that they didn’t belong at a ‘local collaboration table’. JAI had viewed EPT as a potential threat to the success and notoriety of their own training. Sensing the competitive dynamic, EPT became concerned with equity among partners and exhibited a degree of defensiveness about shared leadership within the Collective. Their posture reflected the desire to be seen as deserving and worthy to participate, and was linked to the fear that giving up control would result in being marginalized.

However, the defensiveness was off-putting to other members and sometimes perceived as a desire to take control, a dynamic which threatened the formation of collaborative (shared) governance within the group. This tension was not addressed head on. Although the three partners understood that they were striving for a shared leadership model, they did not assign formal roles and responsibilities as they worked together in the first year because establishing the formal ‘Project Lead’ was one of those roles. The ‘Project Lead’ plays a critical coordination role. Although CSPs are flat networks governed by shared power arrangements [120,121] and joint decision making [122], their “decentralized administrative structures still require a central position for coordinating communication, organizing and disseminating information, and keeping partners alert to the jointly determined rules that govern their relationships” [123] (p. 25).

Avoiding conversations about which individual would serve as the project lead caused TOPS to actively ignore the need for this coordinating role for too long. The earlier tension between JAI and EPT was the backdrop for efforts to mend fences and build trust between the partners by engaging in non-controversial activities and discussions. IDIs revealed a preference from all three NGO leaders “not to step on each other’s toes” and “to focus on trust-building and relationship building” instead of defining internal roles and responsibilities. While research bears out the wisdom of early relationship building [78], avoiding leadership conversations led to a one-and-a-half-year delay in the formation of an internal governance structure. This delay was excessive for a three-year project. It required CSEA to engage in implementation activities without a shared understanding of roles, goals, norms, and power structure, and without the level of trust that is built through the full social learning process. The project lead role was finally settled in June 2019 at the first summit, but the delay was avoidable and could have resolved role confusion and set up accountability structures sooner.

Evolving Governance Structures

Governance structures evolved over time and were aided by the action research process. The action learning surveys consistently identified Strategic Direction and Critical Examination of Goals and Practices as areas where the Collective could improve. When this finding was surfaced for reflection at a Roundtable meeting, CSEA members identified a need for a strategic planning group that would mirror TOPS in the regularity of meetings, and mirror the Roundtable in membership by higher-level members (the NGO presidents, the directors from WMF and Akra), the TOPS’ project lead, and the deputy DA who proxied the district attorney. The project lead and the deputy DA would serve as critical links between the project implementation team and the executive management team, who needed a collaboration table of their own.

The proposal to create this space emerged in 2019 but was not implemented by the project lead until the end of the research period (June 2020). Observation of the dialogue within TOPS about this proposal revealed a reticence to act based on fears that TOPS’ autonomy would be undercut by creating a “leadership group” as it came to be called, and that decision-making power would be taken away from TOPS and replaced by leaders who were “not on the ground, and don’t know the challenges”. Instead of discussing these concerns about roles and inter-spatial communication, TOPS simply did not instantiate this group. The strategic planning group was eventually established at the third summit on governance—a year from the end of the project, and late in the project cycle for project leaders to engage in the full social learning process. Because its charge was to plan for financial and institutional longevity, the delay in creating the strategic planning group negatively impacted CSEA’s sustainability potential.

5.3. Administrative Practices

CSPs are self-governing, but they are not self-administrating. Both the management literature and collaboration scholarship identify coordination, clarifying roles and responsibilities, and monitoring mechanisms as key functions of administration [124]. This research found that information distribution or internal progress reporting constituted a highly important administrative practice, serving as an important feedback loop between TOPS members and Roundtable members.

A progress report is a document or visual that shows the progress that a team is making towards completing a project. It transparently identifies instances and areas where partners are doing well, and areas where they are not meeting objectives; as such, it is one of the few formal accountability mechanisms in a complex partnership. However, producing progress reports was delayed by an unaddressed conflict over how to measure progress. The most basic question for assessing CSEA’s progression was “how many children have received the training so far?” This question had two different answers, depending on which one of two metrics was used. Metric A involved counting how many teachers had been trained and applying the formula that 1 teacher trained = 45 students trained. The logic of this approach derives from the state’s Department of Education reports that a teacher in California on average is responsible for 45 students per semester. Metric B involved directly counting students who had received the training.

Metric B became the CEE’s preferred method because it was more accurate. WMF preferred Metric A because EPT was already keeping track of how many teachers they had trained, and the calculation seemed easy and self-obvious. However, CEE felt that the number of students trained could not be inferred directly from the number of teachers trained, because (a) training teachers did not ensure that teachers would, in fact, use the curriculum with their students and (b) CSEA’s on-the-ground engagement with teachers gave them more accurate estimates of how many students teachers were actually engaging per classroom (approximately 30, not 45). This conflict complicated internal progress reporting, which led to tension between TOPS and WMF. Having cultivated the donor network supporting the Collective’s work—many from among their own clientele—WMF felt it was important to provide regular status updates to the largest donors.

Specifically, WMF had a reasonable expectation that they could ask for, and receive, the most recent project update when they needed it. This expectation was based on their own experiences with how financial and informational reports are handled in their sector. The basic norms of financial reporting are that reports are produced on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis by an accounting software system that performs the desired calculations based on timely data input and integration. However, TOPS had not achieved this level of data production, input, and integration. They did not have the infrastructure—personnel or technological—to input survey data daily, or create real time dashboards and other visuals that could demonstrate progress on KPIs. They lacked an Information System that integrated knowledge and learning from all three organizations. This situation undermined vertical accountability (the accountability of CSEA to major donors) and lateral (horizontal) accountability between partners.

5.4. Accountability

Accountability is closely related to governance. Collaborative governance involves the commitment to joint decision making, and to self-development of the rules and practices by which a CSP will function. However, the key to the success of these choices rests in participants’ willingness to monitor themselves and each other and to impose credible sanctions on noncompliant partners. When collaborative partners are unwilling to monitor their own adherence to the agreed-upon rules, the ability to build credible commitment is lost, and joint decision making is unlikely.

As discussed above, the research found that the primary mechanism for accountability in CSEA was information distribution. Putting in a system of performance monitoring and reporting was also delayed because the Collective was lacking a specialist who could lead internal data and research needs, including monitoring and evaluation. The delay in hiring a monitoring and evaluation (M&E) lead was another impact of the leadership conflict discussed earlier, caused by a conflicting preference between EPT and CEE as to where this individual would be located.

CEE felt it made sense for the person to be located full-time at their headquarters because they were leading the project’s coordination. EPT wanted the new hire to be based part-time at their headquarters. EPT had the most sophisticated data management strategy of the three NGOs and believed that the M&E lead could adapt from their systems what the Collective needed. In addition, EPT’s President still felt marginalized within CSEA and believed that having one more member ‘in their corner’ would increase their centrality or importance within the project.

The difference of opinion was not addressed outright at a TOPS meeting, or interpersonally. This topic avoidance resulted in a long delay in hiring the lead of the only workstream which could address the concerns over data consolidation and progress reporting (Collaborative Data Analysis). With unaddressed disagreement about the performance metrics, and disagreement about where to house the new M&E Lead, progress reporting remained stalled.

The inability of TOPS to generate internal progress reports contributed significantly to the lack of shared understanding between the nonprofits and the private sector partner. As TOPS’ members engaged in outreach, they gradually learned about the obstacles to implementation and scaled back their expectations for how quickly the project could move. Without access to the same information, WMF’s perception of project milestones remained the same. This created a conflict of expectations that was highly pronounced throughout the project, with WMF often expressing frustration about how long it took to perform various things, and the TOPS group expressing frustration at feeling rushed and that private sector partners did not understand the difficulty and nuances of implementation. This was true; the missing feedback loop from TOPS to WMF meant that TOPS members had a highly detailed understanding of the timeline and how long different project aspects were taking, while WMF did not.

6. Discussion

These findings contain several themes that can inform the study and practice of collaborative social projects in anti-trafficking work and other spheres of inter-organizational collaboration. One theme is the importance of iterative dialogue to the development of trust in collaborative governance. Trust is widely described as the most important component of collaboration [125], which is why early phases in a partnership often focus on relationship building. However, trust in partners and in the collaborative process is ultimately built through conflict [64,126] which CSEA avoided both at TOPS and at the Roundtable.

This undermined collaborative governance because trust is essential for establishing shared leadership, while a history of unaddressed conflict can cause a level of distrust that creates barriers for power sharing [127]. A recent study found that shared leadership is positively associated with team effectiveness, both in terms of task performance but also ‘team viability’ [128]. As this study is interested in sustainability, the importance of shared leadership to collaborative governance seems critically important. The low indicators of perceived shared leadership reported on the surveys suggest that CSEA did not perform to its full capabilities.

A second theme concerns power structures. On the one hand, CSEA had a distributed network structure which is appropriate for complex partnerships. The only built-in hierarchies were CSEA’s reporting obligations to Akra Foundation, and the designation of an individual project lead. The Roundtable was a needed bridging mechanism to the periphery of external actors. TOPS was a cross-cutting space that involved almost every partner, a best practice in complex collaboratives. On the other hand, the NGO partners perceived a large power difference between themselves and the private sector partners from WMF. This led to a competitive dynamic between the space facilitated by WMF (the Roundtable), and the space jointly facilitated by the voluntary and public sector partners (TOPS). Unaddressed, this perceived power difference stymied inter-spatial learning within the Collective, and quashed what should have been an early conversation about the size of the overall project.

Another theme concerns the necessity of ICT infrastructure. Effective communication flows between different spaces are among the most important determinants of CSP efficacy and sustainability [129,130]. One implication for other inter-organizational collaboratives is the necessity for a technology platform capable of data integration, impact analysis, shared communication, and real-time monitoring and evaluation. This ICT infrastructure is a vital asset in the formation of complex partnerships, providing three distinct benefits. First, it serves the critical function of facilitating collaboration and communication by making data easier to access and understand. Second, it coordinates work across different technological platforms because each organization comes to the partnership with its own preferred or required IT systems and software. Third, the team can use this technology for real-time monitoring and evaluation. An integrated technology platform makes it possible to track performance on a set of indicators relevant to diverse, high-performing collectives.

An additional theme concerns accountability. Within distributed teams, internal progress reporting is a critical feedback loop that enables coordination and learning. CSEA partners perceived that shared understanding was heavily dependent on them. Most organizations use a software system that helps them keep track of tasks and activities, integrate data, and automate performance monitoring. The private sector has the most experience using ICT to study and boost performance, while the voluntary sector has the least experience with technological data management [131,132,133]. In fact, NGOs have historically demonstrated a robust opposition to the introduction of interactive technology into their organizations [131,134]. During this research, an observable reticence to adopt interactive technology was noted even when the necessity for integrated data systems was clear, and yet CSEA was structured so that the three NGOs drove the bulk of programming and implementation. Future inter-organizational partnerships can draw lessons from CSEA’s experience, perhaps by choosing alternate members to set up (and train others to use) cutting edge information systems.

Finally, these findings also support the conclusion reached by other scholars about the central importance of a facilitator. This role goes by various names: “inclusion management” [135], change management, conflict resolution specialist, facilitated leadership [136], convener, mediator, network manager [137], and others. Especially when the goal is to surface conflict and then work through it constructively, it helps to have a guide—preferably someone skilled in conflict resolution methods, and who understands small group dynamics. Notably, after the spontaneous eruption of conflict behavior described earlier, the following two summits were facilitated by an outside third party.

Limitations of the Study

The main limitation of single-subject design is the difficulty of generalizing their results to other cases, due to the small number of subjects that are investigated. As this is a case study of a singular partnership, its findings require corroboration through quantitative or mixed methods research. In fact, the word ‘findings’ may be too strong; what can safely be said is that this study has generated several working hypotheses, namely that (a) shared understanding is the mediating variable between effective and less effective CSPs, (b) reaching shared understanding requires overt conflict, (c) the majority of individuals in complex partnerships are conflict averse, (d) avoiding engaging in constructive controversy weakens shared understanding, and (e) that partnerships with facilitators who guide constructive conflict are more effective than those without.

There are other study limitations. For instance, it is unclear whether CSEA members ever considered themselves true co-researchers in the action research. While the inquiries about better coordination and communication processes came directly from CSEA members, and they developed the solutions to those problems, the action researcher often played an advocacy role, reminding members of their decisions. There is a fuzzy line between facilitating research, and facilitating follow through. The latter can be perceived as an attempt to control outcomes, and the data suggest that this may have become the case in the latter quarter of the study when the action researcher was assisting with follow-through on problem solutions. Specifically, engagement in the assessing stage declined over the course of the study.

One possibility is that assessing declined precisely due to the collective hesitancy of CSEA members to address conflict head on. As noted, one of the findings in the second survey was the high degree of conflict aversion in the Collective, reported by 85% of members. Understanding that conflict management skills would build greater capacity within CSEA, the action researcher recommended conflict management training for everyone, which has been shown to reduce unconstructive conflict in workplaces [82]. This recommendation was received and then shelved. Ironically, drawing attention to the necessity for constructive conflict may have increased members’ anxiety about conflict itself, reinforcing the use of topic avoidance as a primary coping strategy. An alternative explanation was that work became extremely intensive during the same timeframe as ALS#2 was completed. A large school district had finally come on board, and COVID-19 arrived in March 2020, necessitating CSEA to transition its training online. As one participant observed, “it was hard to find time during the TOPS meetings for anything except project updates”. No matter the cause, the collective learning and evidence-based work planning resulting from the action research became expendable.

An additional limitation of this study is that the action research began after CSEA’s inception. Ideally, action research and other participatory processes should be built into a partnership from the start, making it more likely that the learning cycle will be integrated into regular processes. This study began after CSEA had formed and received funding, just after TOPS had formed and was meeting regularly. The goal of TOPS meetings had already emerged; it was to share various implementation updates, not to reflect on internal performance. As such, it was difficult to root regular conversations about the Collective’s efficacy in the pre-existing format of their conversations.

7. Conclusions

People and organizations increasingly seek to address human trafficking prevention in complex, community-level collaborations that extend beyond the three traditional sectors (nonprofit, public, and private) to include philanthropists, social enterprises, and cross-sectoral institutions such as healthcare, education, and community members. The goal of this paper was to shine a spotlight on conflict in such endeavors—its necessity, the impacts of its presence/absence, and the undermining impacts of conflict avoidance. Space limitations have curtailed the presentation of certain findings, but we can summarize the main effects of conflict avoidance on key process variables (see Table 2).

First, unaddressed conflict about the scope changes undermined shared leadership. Second, lack of stakeholder identification and engagement due to the accelerated timeline caused a significant implementation delay. The causal mechanism was stakeholder analysis, which was not performed. Third, unaddressed relational conflict delayed evolution of the Collective’s governance structure and thus its operability. Fourth, the same unaddressed conflict stalled progress reporting by delaying the M&E specialist’s hire. Fifth, ineffective progress reporting undermined mutual accountability of TOPS members (to each other and to the broader partnership) and undermined interspatial learning more broadly. Finally, the delay in creating the strategic planning group negatively impacted CSEA’s sustainability potential.

Avoidance of controversy can become a strong norm if allowed to take root organically. Multiple studies find that open controversy is a stage within a longer deliberative dialogue process, and that efforts to skip over the conflict stage have negative effects for the other elements of successful partnerships. A framework for harnessing constructive controversy in complex partnerships no doubt has multiple design components, but primary to everything else is a structured conflict management process. One challenge to the creation of this process concerns the nature of grant-driven development projects. Projects that depend on external funding are often designed and constituted through the process of writing a grant proposal. Depending on the time pressure, the proposal writing process can offer plentiful or limited opportunity for iterative dialogue. However, it will still strike most people as odd to invite open controversy during a stage when partners are seeking agreement on how to perform things.

A normative shift is required, from viewing conflict as a problem to viewing conflict as a method of problem solving. The most sustainable partnerships are those that achieve a level of shared understanding about norms, goals, governance, administration, and accountability. Getting to a shared understanding requires a process of problem solving because each partner comes to the table with their own preferences, norms, ideas about the proposed project, and ideas about each other. For example, this study found a large gap in perceived power between non-profit and private sector actors. Is it common for private sector partners to be perceived as more powerful? If so, the research presented in the literature review strongly suggests that conflict avoidance will entrench as a norm. Perceived power difference affects people’s willingness to engage openly with each other. How can power distance be leveled among different kind of actors? What does a robust information system for connecting distributed project teams look like, and what technologies are required? Closing with these questions emphasizes that conflict management should receive greater attention in the study and practice of cross-sector partnerships, and a robust research agenda exists for those who are interested in pursuing it.

Funding

This research was funded by UBS Optimus Foundation, grant number 20190604.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the highly participatory nature of the research methodology, and the situation of participants as co-researchers, equal in standing to the lead investigator with full agency over the methods used to collect, analyze and report data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2020; U.N. Sales No. E.10.Iv.2: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, S.; Cameron, E. Trafficking in Humans: Social, Cultural and Political Dimensions; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, W.H.; Shellman, S.M. Fear of Persecution: Forced Migration, 1952–1995. J. Confl. Resolut. 2004, 48, 723–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foot, K. Collaborating against Human Trafficking: Cross-Sector Challenges and Practices; Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group: Lanham, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dentoni, D.; Hospes, O.; Ross, B. Managing Wicked Problems in Agribusiness: The Role of Multi-Stakeholder Engagements in Value Creation. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Orozco, B.; Rosell, J.A.; Merçon, J.; Bueno, I.; Alatorre-Frenk, G.; Langle-Flores, A.; Lobato, A. Challenges and Strategies in Place-Based Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration for Sustainability: Learning from Experiences in the Global South. Sustainability 2018, 8, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.C. The Role of Conflict Resolution in a Major Urban Partnership to Fight Human Trafficking. Confl. Resolut. Q. 2019, 36, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobbe, L. Analysing Organisational Collaboration Practices for Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadushin, C.; Lindholm, M.; Ryan, D.; Brodsky, A.; Saxe, L. Why It Is So Difficult to Form Effective Community Coalitions. City Community 2005, 4, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.E. Strategic Collaboration Between Nonprofits and Business. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2000, 29, 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative Value Creation: A Review of Partnering Between Nonprofits and Businesses. Part 1. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 726–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle-Hill, R.; Smith, G.; Mazumder, A.; Landham, T.; Goulding, J. Machine learning methods for “wicked” problems: Exploring the complex drivers of modern slavery. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, I.; Cunningham, P.; Drumwright, M.E. Social Alliances: Company-Nonprofit Collaboration. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 58–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattberg, P.; Widerberg, O. Multistakeholder Partnerships: Building-Blocs for Success; International Civil Society Center: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P.H.; William, O. Institutional Logics. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kehyhan, R. Cross-Sectoral Partnerships Can Fight Human Trafficking. In Meeting of the Minds; Meeting of the Minds: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://meetingoftheminds.org/cross-sectoral-partnerships-can-fight-human-trafficking-34944 (accessed on 10 June 2021).