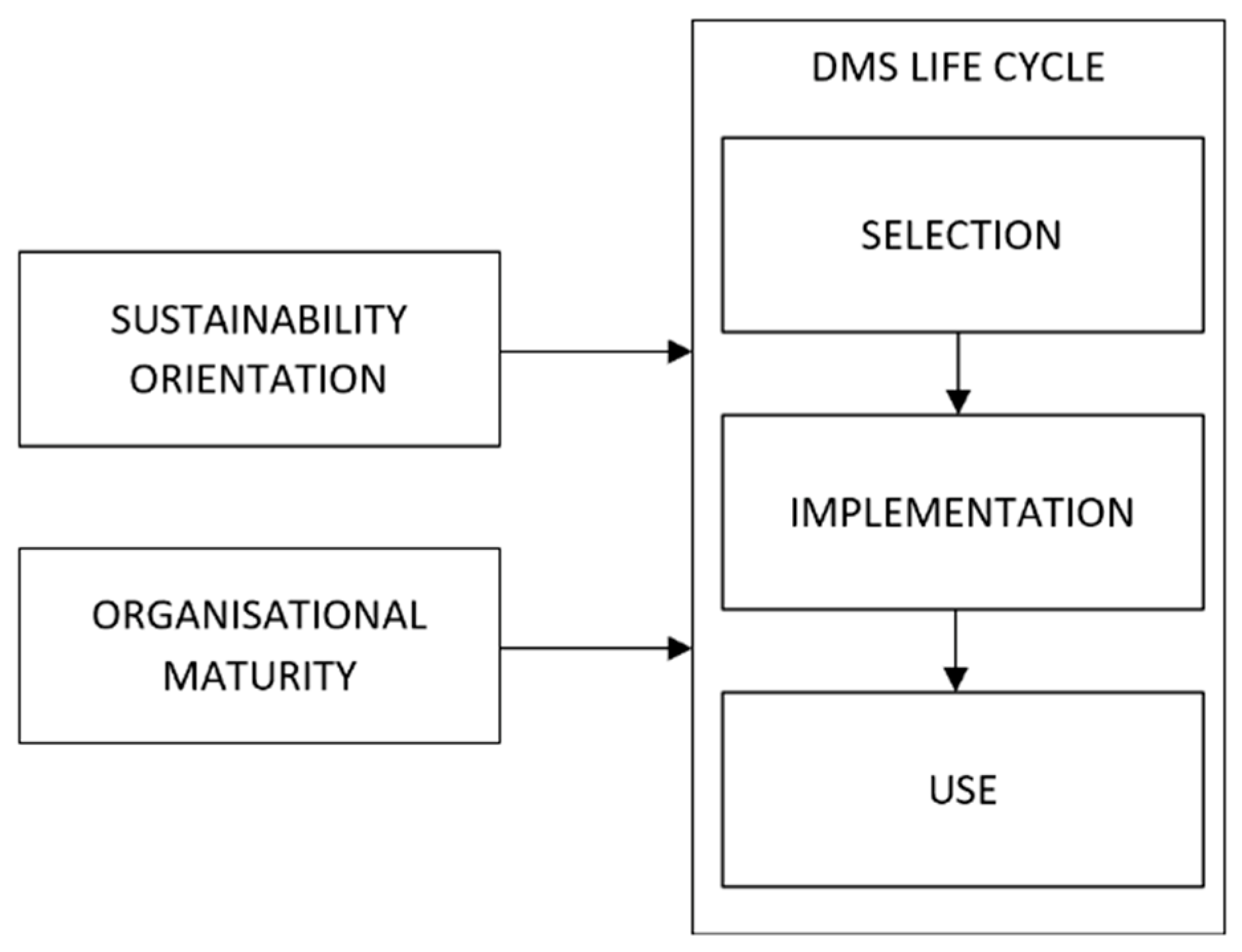

Organizational Maturity and Sustainability Orientation Influence on DMS Life Cycle—Case Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Document Management Systems

- Faster document search. On average, users save 2 to 5 h per week by switching to electronic business.

- Lower costs. Mainly arising from using paper, copying, and storing. In the case of electronic business, all of this is almost eliminated. Storage costs are reduced, as large archive space is not required.

- The profitability of the investment, which is based on a study, amounts from 50% to 84% annually if the implementation is successful.

- Efficiency. Faster and easier access to documentation, time-stealing processes such as document travel around the organization are abandoned; users can access documents remotely, so they do not need to be in one place; the ability to do several things at the same time; and the possibility of group work (documents are stored in shared files that several people can access).

- Security. There is less chance of losing documents, as they are stored electronically; an audit trail is enabled, allowing management to review accesses; and compliance with the standards of archiving, storage, and other business processes must be ensured.

- Costs, such as travel time to photocopy, are reduced. Studies have shown that users waste a lot of time daily by photocopying. It also often happens that going to the photocopier doubles the wasted time, as often users not only stop at the photocopier but also by the colleagues they meet in the corridors or the offices. The number of copies of the same document is also reduced. Organizations and their users often make copies of the same documents, which they use for security if the originals are lost.

- Initial investment. The high initial investment costs are mainly based on purchasing equipment, like computers, printers, scanners, servers, etc.

- Training costs for users and technical staff. Training and education of users and technical staff must be done before DMS use because otherwise, it will not be possible to start the entire process successfully.

- Disrupted system operation. In the event of a system failure, the work stops completely. At that time, the support of technical staff is required.

- Work may be poorly distributed among users. Very often, the work is poorly distributed between users, so there can be a deadlock in the process, putting an additional burden on the work process.

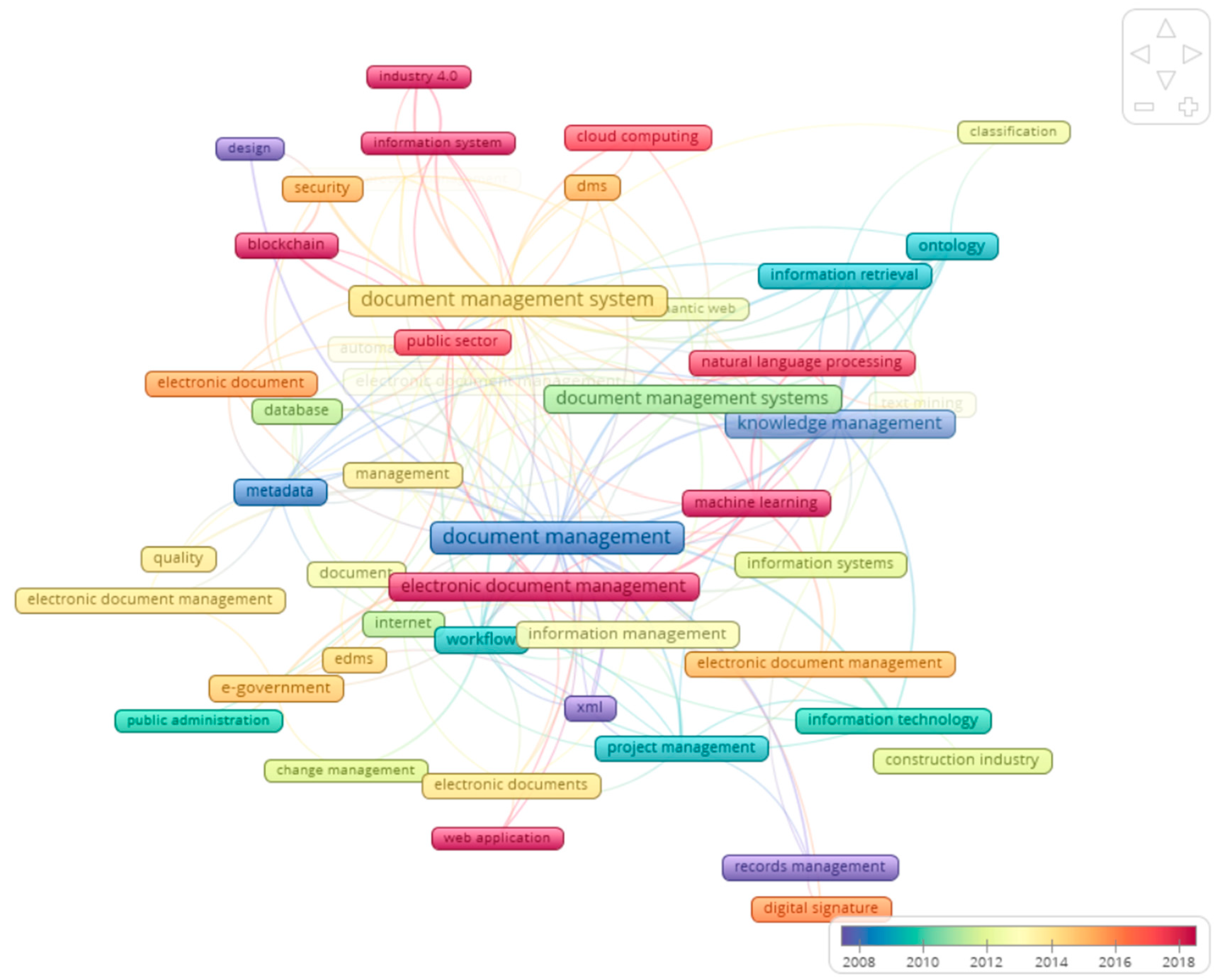

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis

2.3. Business Information Solutions Life Cycle

- Incomplete implementation enables users to use the system only partially.

- Users do not want to use the system in full or do not know how to use it. Therefore, it is necessary to include the users in the implementation at a very early stage.

- Incorrect classification of documents—therefore, it is crucial to harmonize the organizational system and the DMS system.

- Integration problems because the solutions are incompatible with the existing system or among each other.

- Modular solutions, as organizations often implement the solutions in stages.

- People working on the integration are not sufficiently qualified to work with the new technology.

- The process has not been fully reviewed during the preparation phase for the DMS implementation.

2.4. Impact of Organizational Maturity on DMS

- Leadership: style, behavior, disposition, and awareness.

- Culture: attitude to change, duty, customer focus, and teamwork.

- Knowledge: people and methodology.

- Management: process model, integration, and responsibility.

- 5.

- Design: documentation, content, and purpose.

- 6.

- Performers: behavior, skills, and knowledge.

- 7.

- Owner: body, activities, and identity.

- 8.

- Infrastructure: systems for human resources and information systems.

- 9.

- Metrics: use and definition.

- Governance: maturity models can help organizations to establish clear policies and procedures for managing documents, including how to create, store, and destroy them.

- Security: maturity models can help organizations ensure their DMS is secure, including protection against unauthorized access and data breaches.

- Compliance: maturity models can help organizations ensure their DMS complies with relevant regulations and standards, such as ISO 27001, SOC 2, and HIPAA.

- Retention: maturity models can help organizations to manage their documents over their entire document life cycle, including how long to keep them and how to dispose of them.

- Collaboration: maturity models can help organizations to improve collaboration and knowledge sharing among employees by providing a centralized repository for documents.

2.5. Sustainability and DMS

- paper reduction by digitizing documents, reducing the need for printing, and simplifying document sharing and electronic access;

- waste reduction by reducing the amount of paper used and associated waste such as toners, cartridges, etc.;

- compliance with regulations related to sustainability, such as those related to waste reduction, recycling, and carbon emissions, regulation related to the risk of fines and legal penalties, and regulations related to data protection, can help to protect the privacy and security of employees and customers;

- carbon footprint by enabling remote working, which reduces the need for commuting, and by hosting the system on data centers powered by renewable energy sources.

- paperless procurement by implementing sustainable procurement processes, such as sourcing paper from sustainable or FSC-certified suppliers;

- increased efficiency by helping organizations to improve efficiency by automating document-related processes, reducing the need for manual data entry, and increasing the speed of document retrieval;

- cost savings by reducing the need for paper and associated printing and mailing costs and the need for physical storage space;

- increased productivity by making it easier for employees to access and share information, which can help to speed up decision-making and improve collaboration and customer services;

- easier decision-making by providing access to accurate and up-to-date information, which can help to reduce errors and improve the quality of decision-making;

- increased revenue by improving customer service, providing quick access to customer information, and improving collaboration among employees;

- improved employee engagement by making it easier for employees to access and share information, which can help to improve collaboration and knowledge sharing;

- etc.

2.6. Methods and Research Process

3. Results

3.1. DMS Implementation in Company X

- documents can be viewed directly from Hibis screens,

- documents can be captured from the source,

- documents are accessible to the business network promptly,

- the possibility of automated capturing of documents from Hibis to DOMIS,

- quick basic parameterization and initial charging,

- simple and fast adjustments, as there is no coordination between multiple providers,

- user rights are managed faster and applied in HIBIS and DOMIS, and

- the implemented solution would enable Company X to perform their work with almost no paper and become a more socially responsible and sustainable developed company.

- Capturing documents in paper form: digitization of documents (scanning), conversion to a suitable format for long-term storage (PDF/A), and determination of metadata and notes, with the help of which documents can be efficiently searched later in the e-archive system.

- Importing electronic documents into the e-archive system, conversion to a suitable format, and capturing electronic signatures.

- Storage and search of documents through a single interface (in/out interface).

- Digital signing and, if necessary, timestamping of documents.

- Management of electronic documentation in a way that complies with the law, regulations, and recommendations.

- Storage of documents in accordance with their classification and grouping into logical groups (e.g., credit folder).

- The subsequent modification of metadata (e.g., the archiving period for credit documentation).

- Elimination of documents (transfer to the state archive or destruction).

- Required maintenance work in electronic archiving (re-timestamping and signing).

- Access rights management for e-archive documents (based on rights in Hibis) and controlled transmission of the document (separate rights for printing and e-mail).

- Audit trail on the system (accesses to the system) and document level (history of coverage, insights, and controlled intervention).

- 10.

- Give us a short professional background and how do you see cooperation in the project? (Q1)

- 11.

- Were the expectations met (about the cooperation when implementing the solution) (Q2)?

- 12.

- Were the timeline and financial plan agreed upon at the beginning (Q3)?

- 13.

- Would you say that the sustainability orientation of the company influenced the successful implementation(Q4)?

- 14.

- Was the education of the users performed and how (Q5)?

- 15.

- Explain what stage of the maturity model (PEMM) the company was in when the DMS was implemented. Do you think the stage of maturity of the company affected the path of the DMS implementation (Q6)?

- 16.

- Which factors, would you say, were critical for the successful implementation of the solution? Please divide them into the phase of selection, implementation, and use (Q7).

3.2. Structured Interview of the Project Leader on the Side of the Company X

3.3. Structured Interview of the Side of the Solution Provider

4. Discussion

- Cost savings: Managing large amounts of documents brings high financial costs for any organization. With DMS, an organization can automatically, easily, and quickly facilitate the management of processes, which helps significantly reduce costs of printing, human resources, etc., which can be used more efficiently for profitable business processes.

- Time-saving: DMS enables quick and easy access to information without going to the office, which offers users more time for other activities. A simple DMS makes finding data, information, files, and processes easy.

- Improvement of work processes: A good DMS makes it possible to reduce the number of steps required to carry out a procedure or procedures, which directly contributes to an increase in agility and efficiency of work processes as employees will be able to find the information or documents they need for their work faster.

- Regulatory compliance and audit trail: Ensuring compliance with legal norms and regulations and ensuring updates are essential for all businesses. Fulfilling these obligations can be complicated, especially in organizations subject to legal provisions. A suitable DMS will support the implementation of the regulatory and legal framework, protecting data and information. One of the consequences of the last financial crisis was the increase in internal and external audits that many organizations had to undergo to confirm that they had implemented all necessary regulations. DMS enables the recording of all necessary steps to carry out a specific activity.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sambetbayeva, M.; Kuspanova, I.; Yerimbetova, A.; Serikbayeva, S.; Bauyrzhanova, S. Development of Intelligent Electronic Document Management System Model Based on Machine Learning Methods. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2022, 1, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG; EASY SOFTWARE. When Data Drives Experience: Will the Attitude “Digitalization to Improve from Good to Better” Be Good Enough in the Future? 2019. Available online: https://microsite.easy-software.com/en/study-when-data-drives-experience (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Bitkom. Digital Office in Mittelstand 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.bitkom.org/sites/default/files/201910/191021_studie_digital-office-im-mittelstand.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Abbasova, V.S. Main Concepts of the Document Management System Required for Its Implementation in Enterprises. ScienceRise 2020, 1, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriansyah, R.; Elmi, F. Analysis of the Effect of Electronic Document Management System, Organizational Commitment and Work Satisfaction on Employee Performance PT. Graha Fortuna Purnama. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, K.H.; Hanseth, O. Managing path dependency in digital transformation processes: A longitudinal case study of an enterprise document management platform. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 181, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternad Zabukovšek, S.; Tominc, P.; Štrukelj, T.; Bobek, S. Digital Transformation and Business Information Solutions (Digitalna Transformacija in Poslovne Informacijske Rešitve); Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, T.; Kekre, S.; Kalathur, S. Business Value of Information Technology: A Study of Electronic Data Interchange. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limanowski, J.J. On-Line Documentation Systems: History and Issues. Proc. Hum. Factors Soc. Annu. Meet. 1983, 27, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karna, V. Digitalization of Processes; Capgemini: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Khare, S. Gartner BPM Summit 2014: Digitalization of Business Processes; Micropact: Herndon, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ensiger, A.; Fischer, P.; Früh, F.; Halstenbach, V.; Husing, C. Digitale Prozesse. Available online: https://www.bitkom.org/sites/default/files/file/import/160803-Whitepaper-Digitale-Prozesse.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Ernst & Young. Banking & Capital Markets. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/banking-capital-markets (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Haider, A.; Aryati, B.; Mahadi, B. Opportunities and Challenges in Implementing Electronic Document Management Systems. Asian J. Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Abacı, K.; Medeni, I.T. Efficiency of electronic document management systems: A case study. Sci. Educ. Innov. Context Mod. Probl. 2022, 5, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprehe, T.J. A Framework for EDMS/ERMS Integration. Inf. Manag. J. 2004, 38, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Adeneye, Y.B.; Ahmed, M. Corporate social responsibility and company performance. J. Bus. Stud. Q. 2015, 1, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Muminova, S.; Yuldasheva, N.; Safoev, N. Aspects of information security in the electronic document management system (EDMS) for bank system. Res. Educ. 2022, 1, 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R.N.; Abdullayev, V.H.; Abbasova, V.S. Analysis of main requirements for electronic document management systems. ScienceRise 2020, 1, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Paulk, M.C.; Curtis, B.; Chrissis, M.B.; Weber, C.V. Capability maturity model, version 1.1. IEEE Softw. 1993, 10, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, D.M.; Clouse, A.; Turner, R. CMMI Distilled: A Practical Introduction to Integrated Process Improvement, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mettler, T. Maturity assessment models: A design science research approach. Int. J. Soc. Syst. Sci. 2011, 3, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, D.; Borbinha, J. Maturity Models for Information Systems–- A State of the Art. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 100, 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biels. Biels Document Management. Available online: http://biels.com/a-history-of-document-management/ (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Demirtel, H.; Bayram, Ö.G. Efficiency of electronic records management systems: Turkey and example of Ministry of Development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 147, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresko, M. MoReq2: The new model for developing, procuring electronic records management systems. Inf. Manag. 2008, 42, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork, B.C. Electronic document management in construction research issues and results. iTcon 2003, 8, 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, M.J.D. Document Management for the Enterprise: Principles, Techniques and Applications; Wiley Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zantout, H.; Marir, F. Document management systems from current capabilities towards intelligent information retrieval: An overview. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 1999, 19, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babkin, A.V.; Kuzmina, S.N.; Oplesnina, A.V.; Kozlov, A.V. Selection of Tools of Automation of Business Processes of a Manufacturing Enterprise. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference Quality Management, Transport and Information Security, Information Technologies, Sochi, Russia, 23–27 September 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 226–229. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Naser, S.S.; Al Shobaki, M.J. The Impact of Senior Management Support in the Success of the e-DMS. Available online: http://dstore.alazhar.edu.ps/xmlui/handle/123456789/366 (accessed on 3 December 2022).

- Connertz, T. Long-term archiving of digital documents: What efforts are being made in Germany? Learn. Publ. 2003, 16, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague, R.H. Electronic Document Management: Challenges and Opportunities for Information Systems Managers. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canteli, A. Role of Document Management Software in Digital Banking. Available online: https://www.openkm.com/blog/role-of-document-management-software-in-digital-banking.html (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Adam, A. Implementing Electronic Document and Record Management Systems; Auerbach Publications: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wisestep. Top 20 Advantages and Disadvantages of Paperless Office. Available online: https://content.wisestep.com/top-advantages-disadvantages-paperless-office/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Schwartz, R.; Fortune, J.; Horwich, J. AMANDA: A computerized document management system. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1980, 4, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Sanford, C. Influence processes for information technology acceptance: An elaboration likelihood model. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2006, 30, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A.; Perols, J.; Sanford, C. Information technology continuance: A theoretic extension and empirical test. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2008, 49, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J. Methodological Advances in Bibliometric Mapping of Science. 2011. Available online: http://repub.eur.nl/pub/26509/EPS2011247LIS9789058922915.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Moral-Munoz, J.A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Espejo, A.S.; Cobo, M.J. Software tools for conducting bibliometric analysis in science: An up-to-date review. El Prof. De La Inf. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual for VOSviewer Version 1.6.19; Univeristeit Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Measuring Scholarly Impact: Methods and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 285–320. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer v. 1.16.19; Centre for Science and Technology Studies, Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2023; Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Haider, A.; Mahadi, B.; Aryati, B.; Waidah, I. A research framework of electronic document management systems (EDMS) implementation process in government. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2015, 81, 420–431. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, J. 8 Reasons Why ECM Implementations Experience High Failure Rates, and What to Do About It. Available online: https://aiim.typepad.com/aiim_blog/2010/05/8-reasons-ecm-fail.html (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Adam, F.; Sammon, D. The Enterprise Resource Planning Decade: Lesson Learned and Issue for the Future; Idea Group Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C. Causes influencing the effectiveness of the post-implementation ERP system. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2005, 105, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Yasuda, K. Reinventing ERP Life Cycle Model: From Go-Live to Withdrawal. J. Enterp. Resour. Plan. Stud. 2016, 2016, 331270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, T. ERP: A-Z Implemente’s Guide for Success; Resource Publishing: Eau Claire, WI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.Y.; Chiu, A.A.; Chao, P.C.; Arniati, A. Critical Success Factors in Implementing Enterprise Resource Planning Systems for Sustainable Corporations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, P.; MSG. ERP Life Cycle. Available online: https://www.managementstudyguide.com/erp-life-cycle.htm (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Panorama. ERP Implementation Success: How to Break on through to the Other Side (Video). Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCl7ryStY60 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Willaert, P.; Van den Bergh, J.; Willems, J.; Deschoolmeester, D. The Process-Oriented Organisation: A Holistic View Developing a Framework for Business Process Orientation Maturity. In Business Process Management. BPM 2007; Alonso, G., Dadam, P., Rosemann, M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondiau, A.; Mettler, T.; Winter, R. Designing and implementing maturity models in hospitals: An experience report from 5 years of research. Health Inform. J. 2016, 22, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.F.; Nolan, R.L. Managing the Four Stages of EDP Growth. Available online: https://hbr.org/1974/01/managing-the-four-stages-of-edp-growth (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Crosby, P. Quality IS Free; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, C.F.; Kelly, M.A.; Verani, A.R.; Louis, M.E.; Riley, P.L. Development of a Framework to Measure Heath Profession Regulation Strengthening. Eval. Program. Plann. 2014, 46, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockamy III, A.; McCormack, K. The Development of a Supply Chain Management Process Maturity Model Using the Concepts of Business Process Orientation. Supply Chain. Manag. 2004, 9, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashall, S. Improving the Quality of E-Learning: Lessons from the eMM. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2012, 28, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fath-Allah, A.; Cheikhi, L.; Al-Qutaish, R.E.; Idri, A. E-government maturity models: A comparative study. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Appl. 2014, 5, 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Safari, H.; Moslehi, A.; Mohammadian, A.; Farazmand, E.; Haki, K.; Khoshsima, G. E-government maturity model (EGMM). In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, St. Raphael Resort, Limassol, Cyprus, 8–9 October 2018; pp. 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.H.; Ibbs, C.W. Project Management Process Maturity (PM)(2) Model. J. Manag. Eng. 2002, 18, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, A.; Turetken, O.; Reijers, H.A. Business Process Maturity Models: A Systematic Literature Review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2016, 75, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, A.; Erol, S.; Sihn, W. A Maturity Model for Assessing Industry 4.0 Readiness and Maturity of Manufacturing Enterprises. Procedia CIRP 2016, 52, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesson, Y.Y.; Höst, M.; Weyns, K. A review of methods for evaluation of maturity models for process improvement. J. Softw. Evol. Process 2012, 24, 436–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albliwi, S.A.; Antony, J.; Arshed, N. Critical Literature Review on Maturity Models for Business Process Excellence. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Industry Engineering and Engineering Management, Selangor, Malaysia, 9–12 December 2014; pp. 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Koshgoftar, M.; Osman, O. Comparison between maturity models. In Proceedings of the 2nd IEEE International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology, Beijing, China, 8–11 August 2009; Volume 5, pp. 297–301. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, C.J.; Rankin, J.H. The construction industry macro maturity model (CIM3): Theoretical underpinnings. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2012, 61, 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, B. Michael Hammer’s Process and Enterprise Maturity Model. Available online: http://www.bptrends.com/bpt/wp-content/publicationfiles/07-07-ART-HammersPEMM-Power-final.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Crowston, K.; Qin, J. A capability maturity model for scientific data management: Evidence from the literature. Proc. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, G.; O’Regan, G. Capability maturity model integration. In Introduction to Software Process Improvement; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Van Looy, A. Business Process Maturity: A Comparative Study on a Sample of Business Process Maturity Models; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Roglinger, M.; Poppelbuss, J.; Becker, J. Maturity models in business process management. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2012, 18, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronemyr, P.; Danielsson, M. Process Management 1-2-3–maturity model and diagnostics tool. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2013, 24, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M. The process audit. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, W.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A. Sustainable consumption and the quality of life: A micromarketing challenge to the dominant social paradigm. J. Micromark. 1997, 17, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.L.; Bennett, A. Case studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research, Design and Method; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, P.; Steven, A.; Howe, A.; Sheikh, A.; Ashcroft, D.; Smith, P. The Patient Safety Education Study Group. Learning about patient safety: Organisational context and culture in the education of healthcare professionals. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2010, 15, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Baškarada, S. Qualitative Case Study Guidelines. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, J.A.; Gubrium, J.F. Context: Working it up, down and across. Qual. Res. Pract. 2004, 297, 311. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, M.A.; Pursell, E.D.; Brown, B.K. Structured interviewing: Raising the psychometric properties of the employment interview. Pers. Psychol. 1988, 41, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, N.; Durivage, A. The Structured Interview: Enhancing Staff Selection; PUQ: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zillmann, M. Banken–Den Digitalen Wandel Gestalten. Wie Retailbanken die Optionen der, Digitalen Welt “Nutzen. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/de/Documents/financial-services/Branchendossier_Finance_2015_Deloitte.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- HRC. Celostna Rešitev za Bančno Poslovanje (The Entire Banking System in One Place). Available online: https://www.hrc.si/eng/platform (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Raynes, M. Document management: Is the time now right? Work. Study 2002, 51, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlin, P.; Moilanen, M.; Østbye, S.E.; Pesämaa, O. Absorptive capacity, co-creation, and innovation performance: A cross-country analysis of gazelle and nongazelle companies. Balt. J. Manag. 2020, 15, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenamor, J.; Parida, V.; Oghazi, P.; Pesämaa, O.; Wincent, J. Addressing dual embeddedness: The roles of absorptive capacity and appropriability mechanisms in subsidiary performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 78, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, M.; Tanis, C. The Enterprise System Experience—From Adoption to Success. Available online: http://pro.unibz.it/staff/ascime/documents/ERP%20paper.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Esteves-Sousa, J.; Pastor-Collado, J. Towards the Unification of Critical Success Factors for ERP Implementations. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228841545_Towards_the_Unification_of_Critical_Success_Factors_for_ERP_Implementations (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Beheshti, M.; Blaylock, B.K.; Henderson, D.A.; Lollar, J.G. Selection and critical success factors in successful ERP implementation. Compet. Rev. 2014, 24, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Allen, J.C.; Ali, M. An integrated decision support system for ERP implementation in small and medium sized enterprises. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2014, 27, 358–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte & Touche. Your Guide to a Successful ERP Journey–-Top 10 Change Management Challenges for Enterprise Resource Planning Implementations. 2020. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/mx/Documents/human-capital/01_ERP_Top10_Challenges.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Downing, L. Implementing EDMS: Putting People First. Inf. Manag. J. 2006, 40, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alshibly, H.; Chiong, R.; Bao, Y. Investigating the Critical Success Factors for Implementing Electronic Document Management Systems in Governments: Evidence from Jordan. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2016, 33, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, J.; Michels, N.; Robson, J. Triangulation in industrial qualitative case study research: Widening the scope. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 87, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, D.I. A Qualitative Case Study on Achieving Operational Sustainability within a Small Business in the Architectural and Engineering Industry. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/96f454fc3bf1b7996bb107953922d84d/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Sharma, M.; Choubey, A. Green banking initiatives: A qualitative study on Indian banking sector. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaz, A.; Yanartaş, M. An analysis on the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology theory (UTAUT): Acceptance of electronic document management system (EDMS). Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2020, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmez-Turan, A. Does unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) reduce resistance and anxiety of individuals towards a new system? Kybernetes 2020, 49, 1381–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnin, C.H.; Loveridge, D.; Butler, J.B. Business Sustainability Maturity Model. 2005. Available online: https://www.crrconference.org/Previous_conferences/downloads/cagnin.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Vasquez, J.; Aguirre, S.; Puertas, E.; Bruno, G.; Priarone, P.C.; Settineri, L. A sustainability maturity model for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) based on a data analytics evaluation approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Project Leader on the Side of the Company X | Solution Provider | |

|---|---|---|

| Professional background (Q1) | Senior project leader. | Senior project leader. |

| Were the expectations met (Q2)? | Expectations met; prompter responsiveness from provider expected. | Expectations met; not enough human resources dedicated to the project on the company’s side. |

| Timeline and financial plan (Q3) | Timeline plan was not met due to a lack of human resources on the company’s side and slow responsiveness on the provider’s side. Financial plan was not met due to adjustments to the existing system. | Timeline plan was not met due to a lack of human resources on the company’s side. Financial plan was not met due to adjustments to the existing system. |

| Influence of sustainability orientation (Q4) | Indirect influence. | Important factor. |

| Education (Q5) | Education is performed by the project group and provider. | Education is performed by the project group and provider in the form of guidelines, live education, and practical work. |

| Stage of the maturity model (PEMM) (Q6) | Maturity phase 3; maturity stage has a huge influence on the course of DMS implementation. | Maturity phase 3 in some parts, even phase 4: maturity stage is important for the course of DMS implementation. |

| Critical factors (Q7) | Selection phase: management support. Implementation phase: communication, the dedication of employees, and the project team. Use phase: communication. | Selection phase: communication and dedication. Implementation phase: project team and. Use phase: employees and organizational culture. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jordan, S.; Sternad Zabukovšek, S. Organizational Maturity and Sustainability Orientation Influence on DMS Life Cycle—Case Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054308

Jordan S, Sternad Zabukovšek S. Organizational Maturity and Sustainability Orientation Influence on DMS Life Cycle—Case Analysis. Sustainability. 2023; 15(5):4308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054308

Chicago/Turabian StyleJordan, Sandra, and Simona Sternad Zabukovšek. 2023. "Organizational Maturity and Sustainability Orientation Influence on DMS Life Cycle—Case Analysis" Sustainability 15, no. 5: 4308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054308

APA StyleJordan, S., & Sternad Zabukovšek, S. (2023). Organizational Maturity and Sustainability Orientation Influence on DMS Life Cycle—Case Analysis. Sustainability, 15(5), 4308. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15054308