A Systematic Literature Review of Architecture Fostering Green Mindfulness

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Green Mindfulness and Architecture

2.1. Green Mindfulness: A Relevant Concept for Architecture

2.1.1. Definition of Green Mindfulness

2.1.2. Relationship between Mindfulness and Architecture

2.2. Architecture: For Fostering Green Mindfulness as a State of Mindfulness

2.2.1. Architecture in the Studies of Green Mindfulness

2.2.2. Architecture That Tends to Foster Green Mindfulness

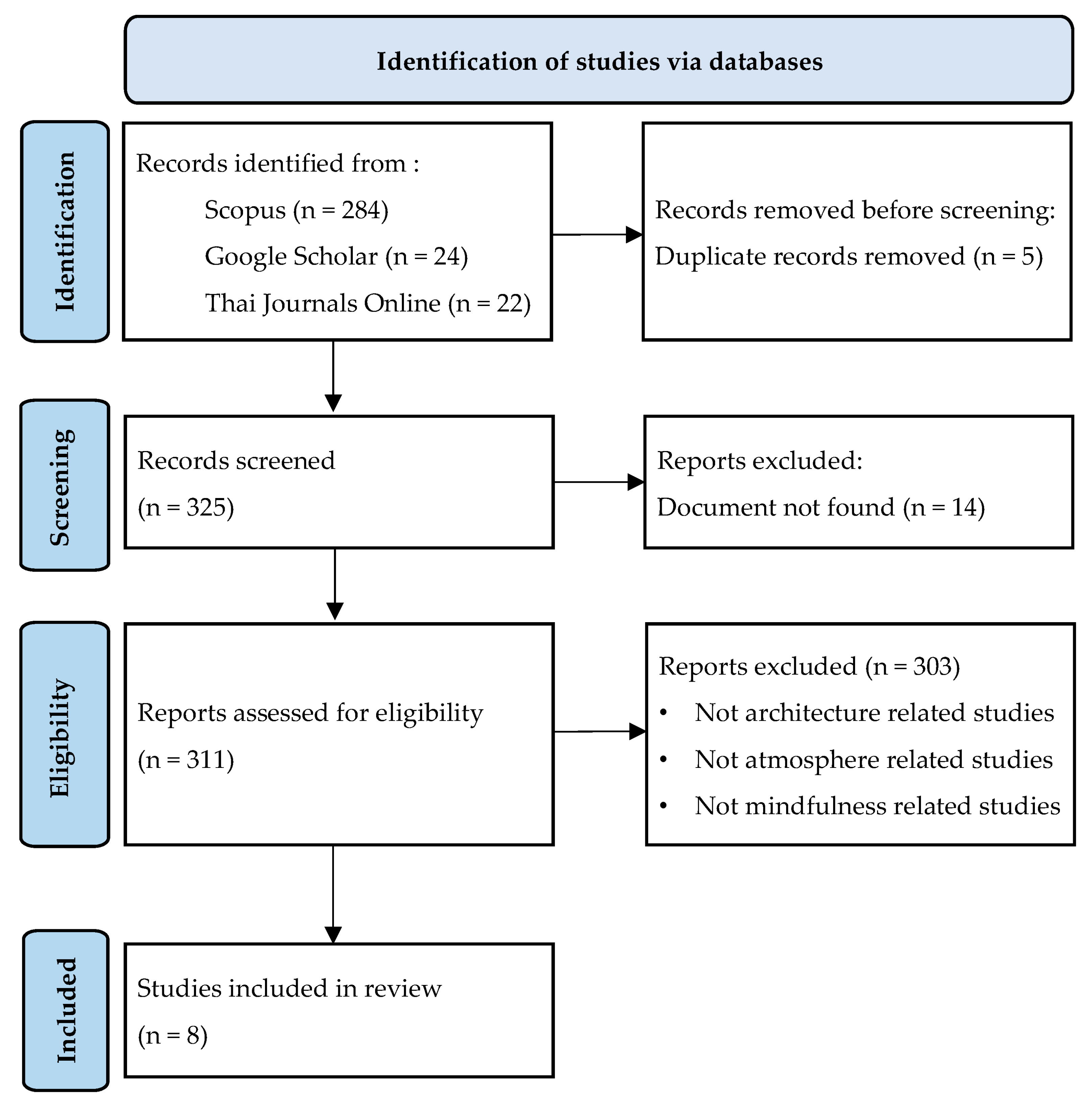

3. Methodology

3.1. Database

3.2. Data Collection

- (1)

- Identification phase

- (2)

- Screening phase

- (3)

- Eligibility phase

- (4)

- Including phase

3.3. Data Analysis

- (1)

- Descriptive analysis

- (2)

- Thematic analysis

4. Results

4.1. Mindfulness and Architecture Publications by Descriptive Analysis

- (1)

- Year of publication

- (2)

- Publishing source

- (3)

- Number of citations

4.2. The Architectures That Tend to Foster Green Mindfulness by Thematic Analysis

4.2.1. Architecture in the Theme of Architectural Atmosphere

- (1)

- Mass and Volume

- (2)

- Material and Object

- (3)

- Color

- (4)

- Light

- (5)

- Sound

- (6)

- Landscape and View

4.2.2. Mindfulness: Fundamental of Green Mindfulness

5. Conclusions

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chansomsak, S.; Vale, B. Can architecture really educate people for sustainability. In Proceedings of the World Sustainable Building Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 21–25 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Satola, D.; Kristiansen, A.B.; Houlihan-Wiberg, A.; Gustavsen, A.; Ma, T.; Wang, R.Z. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Various Energy Efficiency Designs of a Container-Based Housing Unit in China: A Case Study. Build. Environ. 2020, 186, 107358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Poon, C.S. Global Warming Potential and Energy Consumption of Temporary Works in Building Construction: A Case Study in Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 2018, 142, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavinejad, M.; Zia, A.; Larki, A.N.; Ghanavati, S.; Elmi, N. Dilemma of Green and Pseudo Green Architecture Based on LEED Norms in Case of Developing Countries. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2014, 3, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Green Building Council. Building Momentum: National Trends and Prospects for High-Performance Green Buildings; U.S. Green Building Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ragheb, A.; El-Shimy, H.; Ragheb, G. Green Architecture: A Concept of Sustainability. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, L.B. Green Building Literacy: A Framework for Advancing Green Building Education. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2019, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofield, J.H.; Brodnitz, S.; Cornell, J.; Liang, T.; Scofield, T. Energy and Greenhouse Gas Savings for LEED-Certified, U.S. Office Buildings. Energies 2021, 14, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNaughton, P.; Cao, X.; Buonocore, J.; Cedeno, M.; Spengler, J.; Bernstein, A.; Allen, J.G. Energy Savings, Emission Reductions, and Health Co-Benefits of the Green Building Movement. ISEE Conf. Abstr. 2018, 2018, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Energy-Efficiency Standards and Green Building Certification Systems Used by the Department of Defense for Military Construction and Major Renovations; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Lu, Y.; Gou, Z. Green Building Pro-Environment Behaviors: Are Green Users Also Green Buyers? Sustainability 2017, 9, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofield, J.H. Efficacy of LEED-Certification in Reducing Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emission for Large New York City Office Buildings. Energy Build. 2013, 67, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsham, G.R.; Mancini, S.; Birt, B.J. Do LEED-Certified Buildings Save Energy? “Yes, But…”. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuthia, G.T.; Dewi, O.C.; Panjaitan, T.H. Green User and Green Buyer as Supporters for the Achievement of Green Buildings: A Review. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Dwelling Form (IDWELL 2020), Online, 27–28 October 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Zhao, Z.-Y. Green Building Research–Current Status and Future Agenda: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, K.B. Buildings Don’t Use Energy: People Do. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2011, 54, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockton, D.; Harrison, D.; Stanton, N.A. Design for behavior change. Appl. Sci. Psychol. Res. 2010, 67, 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kamilaris, A.; Neovino, J.; Kondepudi, S.; Kalluri, B. A Case Study on the Individual Energy Use of Personal Computers in an Office Setting and Assessment of Various Feedback Types toward Energy Savings. Energy Build. 2015, 104, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, E.M. Green Building, Green Behavior? An Analysis of Building Characteristics That Support Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2020, 53, 409–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty Years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A New Meta-Analysis of Psycho-Social Determinants of pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, M.B.; Jacob, J.C. Mindfulness and Quasi-Religious Meaning Systems: An Empirical Exploration within the Context of Ecological Sustainability and Deep Ecology. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1999, 38, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.C.; Brinkerhoff, M.B. Values, Performance and Subjective Well-Being in the Sustainability Movement: An Elaboration of Multiple Discrepancies Theory. Soc. Indic. Res. 1997, 42, 171–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, N.; Pickett, S.M. Mindfully Green: Examining the Effect of Connectedness to Nature on the Relationship between Mindfulness and Engagement in pro-Environmental Behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.A.; Deale, C. Tapping Mindfulness to Shape Hotel Guests’ Sustainable Behavior. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 55, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, S.; Milne, G.R.; Ross, S.M.; Mick, D.G.; Grier, S.A.; Chugani, S.K.; Chan, S.S.; Gould, S.; Cho, Y.-N.; Dorsey, J.D.; et al. Mindfulness: Its Transformative Potential for Consumer, Societal, and Environmental Well-Being. J. Public Policy Mark. 2016, 35, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Grossman, P.; Schrader, U. Mindfulness and Sustainability: Correlation or Causation? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 28, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yigit, M.K. Investigating the Relationship between Consumer Mindfulness and Sustainable Consumption Behavior. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.M.J. Fashion and the Buddha: What Buddhist Economics and Mindfulness Have to Offer Sustainable Consumption. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2020, 39, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiermann, U.B.; Sheate, W.R. The Way Forward in Mindfulness and Sustainability: A Critical Review and Research Agenda. J. Cogn. Enhanc. 2020, 5, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sethia, N.K.; Srinivas, S. Mindful Consumption: A Customer-Centric Approach to Sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiku, S.O. Institutionalizing Social Responsibility through Workplace Green Behavior. In Contemporary Multicultural Orientations and Practices for Global Leadership; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen-Cico, D.; Hirshfield, L.; Costa, M.R. Measuring the Neural Correlates of Mindfulness with Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy. In Empirical Studies of Contemplative Practices; Nova Science: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 117–145. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E.; Astin, J.A.; Freedman, B. Mechanisms of Mindfulness. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Kang, J.; Jin, H. Architectural Factors Influenced on Physical Environment in Atrium. Renew. Energy Serv. Mank. 2015, 1, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C. Applied Research on Environmental Psychology in Architecture Environment Design. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pécs, Pecs, Hungary, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Architecture (First-Level Discipline). Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%BB%BA%E7%AD%91%E5%AD%A6/228287 (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Environmental Design in Architecture. Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%BB%BA%E7%AD%91%E7%8E%AF%E5%A2%83%E8%AE%BE%E (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Ricci, N. The Psychological Impact of Architectural Design. Bachelor’s Thesis, Claremont McKenna College, Claremont, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles, D.H. Beauty, Neuroscience, and Architecture: Timeless Patterns and Their Impact on Our Well-Being; Fibonacci: Denver, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. The Architectural Spaces and Their Psychological Impacts. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Cognitive Research on Human Perception of Built Envinronment for Health and Wellbeing, Vishakhapatnam, India, 9–10 February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, N.; Bramham, J.; Thomas, M. Mindfulness and Design: Creating Spaces for Well Being. In Proceedings of the 5th International Health Humanities Conference, Sevilla, Spain, 15–17 September 2017; pp. 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Tezel, E.; Giritli, H. Understanding Sustainability Through Mindfulness: A Systematic Review. Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2018, 2, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.S. A Brief Definition of Mindfulness. Behav. Neurosci. 2009, 7, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Barbiero, G. Affective Ecology as Development of Biophilia Hypothesis. Vis. Sustain. 2021, 16, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.; Weisbaum, E. History of Mindfulness and Psychology. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jon Kabat-Zinn Professional Background—Mindfulness Meditation. Available online: https://www.mindfulnesscds.com/pages/about-the-author (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock, G.; Foad, C.M.G.; Thorne, S. How Do People Conceptualize Mindfulness? R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdogan, E. The Effect of Consumer Mindfulness on Green Technology Acceptance. Ph.D Thesis, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Siegling, A.B.; Petrides, K.V. Measures of Trait Mindfulness: Convergent Validity, Shared Dimensionality, and Linkages to the Five-Factor Model. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, H.K.; Williams, P.G. Dispositional Mindfulness: A Critical Review of Construct Validation Research. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 93, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamber, M.D.; Schneider, J.K. Mindfulness-Based Meditation to Decrease Stress and Anxiety in College Students: A Narrative Synthesis of the Research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 18, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiken, L.G.; Garland, E.L.; Bluth, K.; Palsson, O.S.; Gaylord, S.A. From a State to a Trait: Trajectories of State Mindfulness in Meditation during Intervention Predict Changes in Trait Mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 81, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, E.J. Mindfulness; Addison Wesley Longman: Boston, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, S.R.; Lau, M.; Shapiro, S.; Carlson, L.; Anderson, N.D.; Carmody, J.; Segal, Z.V.; Abbey, S.; Speca, M.; Velting, D.; et al. Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2004, 11, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlenberg, R.J. Mindfulness and FAP. In FAP Conference; Functional Analytic Psychotherapy: Seattle, WA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam, N.T.; van Vugt, M.K.; Vago, D.R.; Schmalzl, L.; Saron, C.D.; Olendzki, A.; Meissner, T.; Lazar, S.W.; Kerr, C.E.; Gorchov, J.; et al. Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, F.; Philips, D. Being Mindful about Mindfulness. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 288–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baminiwatta, A.; Solangaarachchi, I. Trends and Developments in Mindfulness Research over 55 Years: A Bibliometric Analysis of Publications Indexed in Web of Science. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 2099–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.S. Mindfulness-Based Interventions: An Antidote to Suffering in the Context of Substance Use, Misuse, and Addiction. Subst. Use Misuse 2014, 49, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gernot, B. Atmosphere as Mindful Physical Presence in Space. Atmos. Mindful Phys. Presence Space 2013, 91, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Inthuyos, P.; Karnsomkrait, L. Enhancing Ambience Product Derived from Clam State of Mind. J. Fine Appl. Arts Khon Kaen Univ. 2018, 10, 226–247. [Google Scholar]

- Atmospheric Architectures; Engels-Schwarzpaul, T., Ed.; Bloomsbury Visual Arts: Bloomsbury, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, G. Atmosphere (Sensu Gernot Böhme); Online Encyclopedia Phylosophy of Nature: Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanizaki, J. Praise of Shadows; Leete’s Island Books: Sedgwick, KS, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Baudrillard, J. The System of Objects; Verso: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Estarli, M.; Barrera, E.S.A.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Diet. 2016, 20, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Siddaway, A.P.; Wood, A.M.; Hedges, L.V. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 70, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radarweg, E.B.V. Dear Floralba del Rocío Aguilar Gordón, Congratulations! On Behalf of the Scopus Content Selection & Advisory Board, We Are Pleased to Inform you that Sophia (1390-3861/1390-8626) Has Conformed to the Quality Criteria and Has Therefore been Accepted for Indexation in Scopus. Edu.ec. Available online: https://sophia.ups.edu.ec/pdf/sophia/Acceptance%20in%20Scopus%20letter-1.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Kamei, F.; Wiese, I.; Lima, C.; Polato, I.; Nepomuceno, V.; Ferreira, W.; Ribeiro, M.; Pena, C.; Cartaxo, B.; Pinto, G.; et al. Grey Literature in Software Engineering: A Critical Review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2021, 138, 106609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ThaiJo2.1: Thai Journal Online. Available online: https://www.tci-thaijo.org (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Kuppako, D. Buddhism in Thai Life: Thai Model for ASEAN. JMA 2018, 3, 138–158. [Google Scholar]

- Teerapanyo, S.; Kumpeerayan, S.; Kaewkoo, J.; Sangsai, P. An Analytical on Jetiya in Thailand. JHUSO 2017, 8, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai, Y. Designing Mindfulness: Spatial Concepts in Traditional Japanese Architecture; Japan Society: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pagunadhammo, P.; Vichai, V.; Chanreang, T. The Analytical Study of The Buddhist Co¬Ncept Appeared in The Pagodas in Chiang Sean City. JMND 2019, 6, 2444–2458. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Simon, M.; Fix, S.; Vivino, A.A.; Bernat, E. Exploring a Sustainable Building’s Impact on Occupant Mental Health and Cognitive Function in a Virtual Environment. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, F. Architecture of Mindfulness: How Architecture Engages the Five Senses. Master’s Thesis, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Porter, N.; Tang, Y. How Does Buddhist Contemplative Space Facilitate the Practice of Mindfulness? Religions 2022, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Dimensions, Elements, and Attributes of Biophilic Design. In Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; Heerwagen, J., Mador, M., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MS, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R. Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-Nature Connection; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M. Trends in Mindfulness Research over the Past 55 Years. Available online: https://www.mindful.org/trends-in-mindfulness-research-over-the-past-55-years/ (accessed on 2 February 2023).

| Article Title | Author | Year | Source | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere as Mindful Physical Presence in Space [63] | Böhme G | 2013 | OASE Journal for Architecture | [41] |

| An Analytical on Jetiya in Thailand [75] | Teerapanyo S, Kumpeerayan S, Kaewkoo J, Sangsai P | 2017 | Humanities and Social Sciences Journal Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University | – |

| Designing Mindfulness: Spatial Concepts in Traditional Japanese Architecture [76] | Kawai Y | 2018 | Interview in Japan Society Talk | [4] |

| The Analytical Study of the Buddhist Concept Appeared in the Pagodas in Chiang Sean City [77] | Pagunadhammo P, Vichai V, Chanreang T | 2019 | Journal of MCU Nakhondhat | – |

| Affective Ecology as Development of Biophilia Hypothesis [44] | Barbiero G | 2021 | Visions for Sustainability | [6] |

| Exploring a Sustainable Building’s Impact on Occupant Mental Health and Cognitive Function in a Virtual Environment [78] | Hu M, Simon M, Fix S, Vivino A, Bernat E | 2021 | Scientific reports | [10] |

| Architecture of Mindfulness: How Architecture Engages the Five Senses [79] | Sadeghi F | 2021 | University of Memphis Digital Commons | – |

| How Does Buddhist Contemplative Space Facilitate the Practice of Mindfulness? [80] | Chen A, Porter N, Tang Y | 2022 | Religions | – |

| Author (Year) | Mass and Volume | Material and Object | Color | Light | Sound | Landscape and View | Mindfulness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Böhme G (2013) [63] | Atmosphere

| - | Synesthetic | Synesthetic | Synesthetic | - | One enters or finds oneself by mind and body (mindful body) |

| Teerapanyo S, Kumpeerayan S, Kaewkoo J, Sangsai P (2017) [75] | - | The Trick Lotus Jetiya in Thailand | - | - | - | - | The teaching of the four foundations of mindfulness |

| Kawai Y (2018) [76] | Traditional Japanese architecture:

| Michiyuki (Travelling)

| Utsuroi (transience):

| Yugen (unknown):

| - | Hashi (edge):

| Mind and body are connected with space |

| Pagunadhammo P, Vichai V, Chanreang T (2019) [77] | - | The Basement of Chedi in Chiang Sean | - | - | - | - | The signification of mindfulness or insight meditation |

| Barbiero G (2021) [44] |

| Natural material | - | Natural light | - |

|

|

| Hu M, Simon M, Fix S, Vivino A, Bernat E (2021) [78] | Exposure to nature |

| - |

| - |

|

|

| Sadeghi F (2021) [79] | Connection to nature |

|

|

| Amplified sound |

|

|

| Chen A, Porter N, Tang Y (2022) [80] |

|

| Due to environment and climate:

| Natural light |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thampanichwat, C.; Moorapun, C.; Bunyarittikit, S.; Suphavarophas, P.; Phaibulputhipong, P. A Systematic Literature Review of Architecture Fostering Green Mindfulness. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043823

Thampanichwat C, Moorapun C, Bunyarittikit S, Suphavarophas P, Phaibulputhipong P. A Systematic Literature Review of Architecture Fostering Green Mindfulness. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043823

Chicago/Turabian StyleThampanichwat, Chaniporn, Chumporn Moorapun, Suphat Bunyarittikit, Phattranis Suphavarophas, and Prima Phaibulputhipong. 2023. "A Systematic Literature Review of Architecture Fostering Green Mindfulness" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043823

APA StyleThampanichwat, C., Moorapun, C., Bunyarittikit, S., Suphavarophas, P., & Phaibulputhipong, P. (2023). A Systematic Literature Review of Architecture Fostering Green Mindfulness. Sustainability, 15(4), 3823. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043823