Abstract

This study aimed to determine the impact of teacher verbal encouragement on physical fitness performance, technical skill, and physiological responses during small-sided soccer games (SSGs) of adolescent female students’ during a physical education session. Fifty-two adolescent female students were divided into a verbal encouragement group (VEG, 15.57 ± 0.50 years) and a contrast group (CG, 15.50 ± 0.51 years). Anthropometric measurements, soccer-specific cardiorespiratory endurance (Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 1; YYIRT1), muscle power (countermovement jump (CMJ); 5-jump-test (5JT), agility (t-test), sprint speed (30 m)), technical skill, and heart rate (HR) responses during SSG were measured. Additionally, heart rate (HR) was recorded throughout the SSG, and video analysis was used to quantify technical actions. The independent samples Student’s t-test was used to compare the difference between the verbal encouragement group and the CG. There was no difference between the verbal encouragement group and the CG in anthropometric characteristics and 30 m speed (p > 0.05). The total distance measured with YO-YOIRT level 1, t-test performance, CMJ, and 5JT performance results of the verbal encouragement group were considerably higher than the CG (p = 0.001, ES = 1.8, large; p = 0.001, ES = 1.09, large; and p = 0.001, ES = 1.15, large, respectively). Furthermore, the ball contacts, successful balls, and average heart rate were higher in the verbal encouragement group compared with the CG (p = 0.001, ES = 3.69, large; p = 0.001, ES = 5.25, large; and p = 0.001, ES = 5.14, large, respectively). These results could inform teachers of the usefulness of verbal encouragement in the teaching-learning process in the school setting during small-sided soccer games.

1. Introduction

To obtain objective information about the capacities of students during physical education sessions, teachers are called upon to test their students on all technical, tactical, and physical levels. It can be difficult to motivate students to reach their maximum effort during the drill, which is why the test results could be impacted by many variables. The most important role in this process is played by motivation—the incentive for people’s actions, desires, and needs [1]. Moreover, positive feedback could be effectively used in physical activity as a stimulus for intrinsic motivation [2,3]. The student-teacher interaction might also impact the physical education training process and its outcome. In fact, the teacher’s behavior is determined by their communicative, integrative, and methodological strategies [4,5]. Some studies mentioned that students are motivated by a desire to compete and a need for challenge, and teachers must take into consideration the types of communication and methods that motivate the students and to which they respond positively [6]. Learning happens when a response is conditioned to a stimulus [4]. Positive feedback could be effectively used in physical activity as a stimulus for intrinsic motivation [7]. Verbal encouragement is another motivational stimulus that can be used during physical education lessons. Verbal encouragement is quite often used to motivate athletes to keep or increase effort during exercising or testing. It is recommended in several drill testing rules as a positive stimulus for their performance [8,9]. In regards to communication strategies, verbal behavior, such as general technical rules and positive verbal encouragement (VE), can affect physical skills and mood in pupils and athletes. Studies have shown that performance can be affected by technical, tactical, and physical factors [10,11]. Other studies have pointed out that coach encouragement (CE) represents a crucial factor for training and exercise motivation, especially among young players [12,13]. Rampinini et al. [14] proved that physiological responses such as heart rate (HR), blood lactate concentration, and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) were all much higher during exercises with a coach’s encouragement. In the same way, Selmi et al. [13] found significant positive effects of coach encouragement on the young soccer players’ HR, RPE, and levels of enjoyment responses in game-based training. So, using verbal encouragement was proven to ameliorate motivation and physical performance in various circumstances and activities during integrated training situations. Verbal encouragement given by a coach or a teacher is thought to be a form of external motivation that positively influences positive behavior, physical engagement, and the desire to train [13,15,16,17]. In the same way, Rube and Secher [18] mentioned that verbal encouragement can be used to improve aerobic and anaerobic fitness. While various studies have investigated the effects of coach encouragement in professional clubs, they have shown that winning championships, particularly in soccer, remains their top priority [12,19]. Recently, Sahli et al. [20] have analyzed the effects of verbal encouragement and improvements in the performance during the repeated change-of-direction (RCOD) sprint test. They had examined the effects of general technical guidelines and combined positive verbal encouragement on the pupils’ technical and psychophysiological parameters during a small-sided handball passing game. Schoolboys made up the populations of both studies. Our information indicates that a very small number of studies have examined the impact of verbal encouragement on physiological and technical characteristics assessed during soccer-specific training, as well as on physical development during physical education sessions in young students [13,15,17]. Thus, such analysis can help to better understand the impact of verbal encouragement on the intensity of the student on a physical and technical level, thus constituting an interesting approach to improving the teaching and learning process. In the same way, encouragement can be determined as an additional task condition to adjust the conditions of practice, especially since our study population is young adolescent girls who practice football at school. Therefore, this study aimed to observe the effects of verbal encouragement on physical fitness tests, technical skill, and physiological responses during small-sided soccer games among adolescent female students. We hypothesized that the presence of verbal encouragement from the teacher would result in improvements in physical fitness tests, technical skill, and physiological responses during small-sided soccer games for adolescent female students.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Fifty-two adolescent girls enrolled in one secondary school were involved in this investigation. Participants were divided into two groups: 26 girls were allocated to verbal encouragement group (VEG, 16.5 ± 0.4 years) and 26 girls were assigned to the contrast group (CG, 16.3 ± 0.3 years). Randomization was conducted based on a single sequence of random assignments that was used to allocate subjects into verbal encouragement group (VEG) and contrast group (CG) [21]. No significant intergroup difference in age and anthropometric data was found (Table 1). Participants regularly participated in physical education classes (i.e., two sessions per week), including different cycles in team sports (i.e., handball, basketball, soccer, and volleyball) and individual sports (i.e., athletics and gymnastics).

Table 1.

Anthropometric characteristics of verbal encouragement group and control group determined at the end of the school year.

All participants provided written, informed consent before participating. All participants had no reported injuries or illnesses one month before the study and during the study. During the testing period, all participants were instructed to maintain their usual physical activity routine. The participants were asked to follow their normal diet during the time of the study. No dropouts were reported during the experimental period. Prior to the study, written informed consent for participation was obtained from each subject and their parents or guardians, and the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of High Institute of Sport and Physical Education of Kef, Tunisia. Furthermore, the present study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and its latest amendments.

2.2. Experimental Procedures

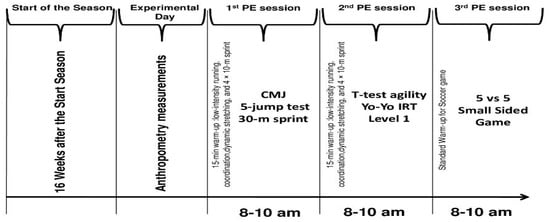

This study had a cross-sectional design. The investigation took place during the 2021–2022 school mid-season (16 weeks after the beginning of the season). Before beginning the experimental testing, anthropometric measurements were taken. In the experimental days, testing was performed during 3 consecutive physical education sessions (during regular physical education sessions). Across the three testing sessions, all participants performed a standardized 15 min warm-up that consisted of low-intensity running, coordination movements and dynamic stretching (i.e., high knee lifts, butt kicks, straight-line skipping, etc.) and 4 × 10 m sprint. On the first session, participants performed a CMJ, a 5-jump test (5JT), and a 30 m sprint. During the second session, participants performed the t-test for agility and a Yo-Yo IRT Level 1. On the third session, in addition to the standardized warm-up, the girls do simple technical tasks with the soccer ball, and they performed a 5 vs. 5 SSG with four supporting players and without goalkeeper (Figure 1). In order to determine the impact of teacher verbal encouragement on the performance of girls during the physical, technical and physiological tests in this study, we chose these test measures [YYIRT1, CMJ; 5JT, t-test, sprint speed (30 m); technical skill; and HR responses during SSG)] and not others. These tests are easy to perform in practice and do not require a lot of materials. Moreover, the participants were familiarized and accustomed to these tests. In each testing protocol, the verbal encouragement group performed the SSG with teacher’s verbal encouragement, and the contrast group performed the SSG without verbal encouragement. Among the verbal encouragement group, the physical education teacher encourages the students using specific instruction (i.e., “Go, go, go,” “Well done,” “Again, again,” “Go, great courage,” “Go ahead, try again,” “Come on, you will get there,” “Trust yourself, and you can”) [22]. All assessments were conducted on the same synthetic pitch grass to limit the effects of circadian variations on the measured variables. The tests were performed on the same synthetic pitch and at the same hours (8:00–10:00) to avoid any potential diurnal variation of performance. All test procedures were supervised by the same assessors, and all students’ girls were familiarized with all test procedures. In the school, the sports field is very wide, and the two groups work separately. When the teacher encourages the experimental group, the contrast group does not listen to the teacher’s intervention.

Figure 1.

Representative diagram of the experimental protocol.

2.3. Anthropometry Characteristics

Each participant came to the school infirmary for a medical examination and anthropometric measurements performed by school pediatrician. Body height and weight of each subject were measured using standard techniques to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively. The adiposity was assessed by measuring skinfold thickness at four sites on the left side of the body (i.e., triceps, biceps, subscapular and suprailiac) using a Harpenden skinfold calliper (British Indicators Ltd., Luton, UK) to calculate the percentage of body fat (% body fat), based on the equations by During and Webster [23]. All assessments were made at 8 ha·m. before beginning the investigation.

2.4. Puberty Stage Assessment

The indicator of biological maturity status was the puberty stage. It was noted by a pediatrician experienced in the assessment of secondary sex characteristics according to Tanner’s method [24]. Children at pubertal development stages 1–5 were evaluated. According to their pubescent status, the female students belonged to Tanner stage (4–5).

2.5. Physical Fitness Characteristics

2.5.1. The Jumps

Each participant performed counter movement jump (CMJ), starting from a standing position allowing for counter movement and intending to reach knee-bending angles of around 90° just before propulsion. The ground reaction forces generated during these vertical jumps were estimated with an ergo jump (Opto Jump Microgate, Bolzano, Italy). Additionally, the participants performed a five-jump test (5JT). The 5JT consists of 5 consecutive strides with joined feet position at the start and end of the jumps. From the joined feet starting position, the participant was not allowed to perform any back step with any foot; rather, he had to directly jump to the front with a leg of his choice. After the first 4 strides, i.e., alternating left and right feet for 2 times each, he had to perform the last stride and end the test again with joined feet. A 5JT performance was measured with a tape from the front edge of the player’s feet in the starting position to the rear edges of the feet in the final position. Each player performed 2 CMJ and 2 5JT, with a one-minute break in between, with the best (highest) jump of each type being used for analysis [25].

2.5.2. Running Speed Test

The time needed to cover 30 m was measured with a photocell timing system (Brower Timing System, Salt Lake City, UT, USA). The participants ran as fast as they could, performing three trials in total. There was a 3 min recovery period between each trial. The best (fastest) 30 m sprint time was selected for analysis. The results show that these tests were highly repeatable: intra-class correlation (ICC) 30 m sprint, ICC = 97; CMJ, ICC = 0.92; 5JT, ICC = 0.90.

2.5.3. Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 1

The Yo-Yo IRT Level 1 test was performed according to the procedures described by Krustrupet et al. [26]. Briefly, the YoYoIRTL1 consists of repeated 20 m runs back and forth between a starting, turning, and finishing line, at a progressively increased speed, controlled by an audio metronome. Participants had a 10 s active rest period (decelerating and walking back to the starting line) between each running bout. Participants stopped of their own volition or were mandatorily withdrawn from the test if they failed to reach the finish line in time on two occasions. The total distance covered was recorded for analysis.

2.5.4. Agility (t-Test)

The t-test is a measure of multidirectional agility and body control that evaluates an individual’s ability to change directions rapidly while maintaining balance and speed [27]. Performance in the t-test was measured with infrared photoelectric cells (Cell Kit Speed Brower, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.6. Small-Sided Games

A 5 vs. 5 + 4 format (no goalkeepers) was carried out on a 35 × 25 m synthetic pitch (~88 m2 per player) was carried out. The four supporting players play with the team in possession of the ball but outside the playing surface. Each match lasted 10 min. All matches were timed by a digital stopwatch (Casio HS-3, Casio Electronics Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China). The PE teacher kept moving the perimeter of the court, at the same time encouraging the female students using soccer-specific terminology and vocabulary (i.e., “Again, Again”, “Attack the ball”, “Go, Go, Go”, “Intercept the ball”, “Keep the ball”, “Move”, “Seek the ball” [17], and providing new balls when necessary to keep the subjects playing continuously during the drill [14,28,29]. The provided encouragement was impromptu, based on the game situation, the position of the players and their movement in the court, space occupation, and ball circulation. The subjects were asked to play with maximum effort over the course of the exercise and to maintain possession of the ball for the longest possible time. The number of ball touches authorized per individual possession was set at three to ensure that all subjects engaged in the SSG. For supporting players, only one touch of the ball is needed to speed up the game. During the CG game, the physical education teacher stood near the court, providing new balls when necessary but not providing any verbal encouragement.

2.7. Physiological and Technical Evaluations

HR was recorded following the warmup using the Polar H9, which is an ideal all-round HR monitor that connects to a wide range of devices. HR was continuously monitored throughout the SSG and recorded. After each session, all HR data were downloaded to a PC via computer interface using dedicated software and stored. The mean HR for each participant were calculated for each game and used for analysis to provide an indication of the overall intensity of the SSG. Moreover, all players were filmed for the entire 10 min duration of the match using a video camera (Sony, HDR-CX240E, Chengdu, China) to determine their work rate profiles during each SSG. The video camera was positioned on an elevated platform on the half-way line of each pitch and set back 10 m from the sideline [30]. Players were filmed in each game, and none of the participants had any knowledge that they were being recorded at that specific moment. The video tapes were then replayed, and the number of technical actions completed by each player was also recorded. These were cumulated for the entire 10 min game period and reported as the total number of balls played as well as the number of successful balls.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The data is put forward as mean (M) ± standard deviation (SD). Before using parametric tests, the normality hypothesis was verified using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The independent group Student’s t-test was used to compare the verbal encouragement group and the CG. The magnitude of change expressed by Cohen’s d coefficient has been used to give a careful judgment on the differences between verbal encouragement group and CG [31]. The magnitude scales were considered trivial, small, medium, and large, respectively, for values of 0 to 0.20, >0.20 to 0.50, >0.50 to 0.80, and >0.80 [32]. Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (v26.0, SPSS, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the encouragement verbal group (VEG) and the contrast group (CG) in terms of anthropometric variables (height, weight, and % body fat).

The total distance covered in YYTR1 by the verbal encouragement group is significantly higher than that of the CG, with a large marginal of change (p < 0.001; ES = 1.85). In addition, there is a significant difference in t-test times between the VEG and the CG (p < 0.001), with ES equal to 1.40. However, there is no significant difference in 30 m speed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sprinting, agility, and aerobic measurements for verbal encouragement group and contrast group.

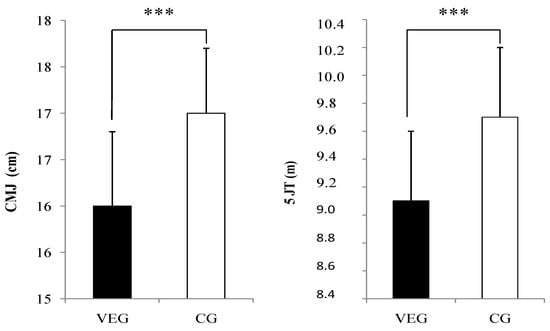

The CMJ and 5JT performance indices were displayed in Figure 2. The results show that those of the VEG were significantly higher than those of the CG (p < 0.001) with large marginal of change (CMJ: ES = 1.09; 5JT: ES = 1.15).

Figure 2.

Comparison of jumping measurements between verbal encouragement group and contrast group. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviations. VEG: verbal encouragement group; CG: contrast group; CMJ: countermovement jump; 5JT: five-jump-test, *** p < 0.001.

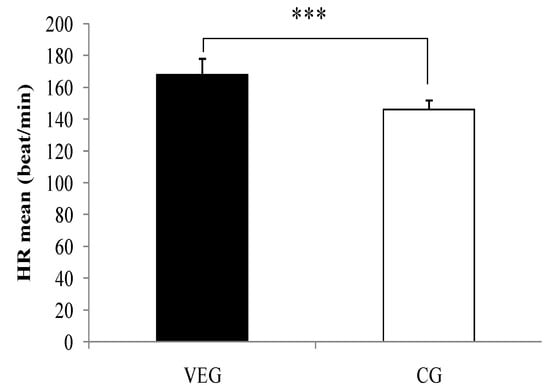

The result of the present study showed that mean HR was higher in the verbal encouragement group compared with the CG (p 0.001, ES = 5.41) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean heart rate between verbal encouragement group and contrast group. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviations. VEG: verbal encouragement group; CG: control group; mean HR: mean heart rate, *** p < 0.001.

Similarly, for Balls C and S Balls, a significant difference was observed for the verbal encouragement group compared with the CG with the large (ES = 3.69, 5.25, and 5.41, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of contacts and successful ball and mean heart rate responses for 4 vs. 4 small-sided games for verbal encouragement group and contrast group.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of teacher verbal encouragement on physical fitness performance, technical skill, and physiological responses during small-sided soccer games (SSGs) of adolescent female students during a physical education session. The results confirm the hypothesis that the presence of verbal encouragement from the teacher would result in an improvement on physical fitness tests, technical skill, and physiological responses during small-sided soccer games for adolescent Tunisian female students. The results of the present study were as follows: (1) The total distance covered in YO-YO IRT level 1, t-test performance, CMJ, and 5JT performance results of the verbal encouragement group were significantly higher than the CG. (2) The number of ball contacts and successful balls were greater in the verbal encouragement group. (3) The average HR was higher in the verbal encouragement group compared with the contrast group. In the modern school, the educational strategy is changing; new educational standards are being created; and new programs are being developed that require the creation of innovative methods of teaching that are oriented toward the development of communicative and speech activities and the personalities of the students. So, we can say that our education system follows new trends in relation to the teaching-learning process in the school environment in relation to the physical education program. Our result is in line with Andreacci et al. [33], who demonstrate that verbal encouragement can be used to improve the aerobic performance during maximal exercise testing. In the same way, Wang et al. [34] mentioned that the students’ education engagement was found to be positively related to teacher care and encouragements [34]. Other studies have gotten similar results and observed the beneficial effects of verbal encouragement on the performance of athletes on a muscular endurance task compared with subjects without VE [35]. Moreover, the present results align with some previous studies that have shown the beneficial effects of VE on physical performance. Edwards et al. [36] observed that the verbal encouragement motivated subjects by improving their physical performance during aerobic exercises. The verbal encouragement’s positive effect was noted during aerobic tests on athletes [15,37].

For muscle power, the performance of the countermovement jump (CMJ) and 5-jump-test (5JT) were significantly higher in the verbal encouragement group compared with the CG, confirming a recent study by Vasconcelos et al. [38], who showed that the verbal encouragement leads to improvement in squat jump and countermovement jump performance for futsal soccer players. Miller et al. [39] indicated that the training with VE produced high improvements in strength performance in male students. Eventually, Lee et al. [40] and Belkhiria et al. [41] mentioned that significant changes in verbal encouragement were found in the force production. In terms of a 30 m sprint, the performance was not changed between the verbal encouragement group and the CG, and this result does not correspond to the study of Edwards et al. [36], who indicated a significant improvement in cycling sprints with verbal encouragement, suggesting that verbal encouragement has an important role in longer duration sprint exercises than short distance sprints. In terms of agility, the present study showed a significant difference between groups in favor of the verbal encouragement group compared with the CG. Our results have been confirmed by Hammami et al. [42], who reported the positive influence of the verbal encouragement in the sprint with change of direction performance in adolescent student players.

The use of SSGs in physical education sessions is of major importance for student learning. A lot of studies showed the beneficial effects of SSG on mental, physical, tactical, and technical parameters during training and in a learning situation [13,17,43,44]. Moreover, the SSGs provide students with more learning experiences, improving their decision-making opportunities, and leading to educational success [45]. Sahli et al. [17] examined the effect of verbal encouragement given by physical education teachers during SSG on the players’ physical enjoyment and psychophysiological responses. They showed that SSG induced a higher rate of perceived exertion (RPE), higher physiological responses, and a more positive mood with better enjoyment in junior players in a verbal encouragement context. In the same way, small game-based drills with fewer rules became the most effective in improving the sports initiation of both professional players and PE pupils [13,46,47].

Our results showed a significant difference for the verbal encouragement group compared with the CG for ball contacts, successful balls, and mean HR. Many studies on SSGs have mentioned the significant role that the coach’s verbal encouragement has on the game intensity, expressed as physiological responses and internal intensity [13,15,48]. In the same way, verbal encouragement has been shown to improve physical performance and motivation in various contexts and activities, including SSG. This conclusion supports the data from Rampinini et al. [14], who examined the influence of verbal encouragement on various physiological aspects in several SSG formats on small, medium, and large pitches. They showed that HR, [La], and RPE values were significantly greater in SSGs when the physical education teacher gave verbal encouragement. Additionally, Selmi et al. [13] compared the effects of verbal encouragement from the coach on youth soccer players’ physiological responses during 4 vs. 4 SSGs. Researchers have also indicated that RPE and %HR max were higher in SSGs with encouragement compared with SSGs without encouragement.

For technical skill, Jones and Drust [49] mentioned that the total number of ball contacts assessed was among the indices for determining the technical requirement. Reducing the number of players in the game significantly increased the number of individual ball contacts per game. Sahli et al. [20] showed that verbal encouragement helped students increase their number of passes in a small-sided handball passing game drill. In the same way, several studies indicated that exercises based on small games with fewer rules in physical education sessions at school are currently used the most to improve the sports initiation of students, especially in team sports (i.e., soccer, handball, basketball, volleyball) [13,44,47]. Other research indicated that the number of passes and the dribble improved during a SSG with the use of technical instruction [50]. These results showed that verbal encouragement motivates players to engage physically at a high level and keep possession of the ball for the longest possible time. It should also be noted that the current results contradict the conclusions of Brandes and Elvers [12], who signaled a decline in the levels of physical load using technical instructions during SSG.

These discrepancies may be a result of the instructors’ encouragement and behavior, and some studies have shown that certain abilities and attitudes have a transferable effect on instructors’ verbal reactions during youth soccer games. These efficacy dimensions have the potential to influence instructors’ confidence in their capacity to affect athletes’ psychological well-being and positive attitudes. There are opinions that refer to the fact that the use of encouragement interventions can be associated with increases in the satisfaction of those involved in the activities [51,52,53].

Added to the impact of the psychological experiences of the students on their emotions and learning strategies, the influence and significance of teachers’ teaching styles are also indicated [54,55]. One should consider several limitations when interpreting the current results. One of the main ones is related to the small sample size, which makes any generalization difficult. Furthermore, we used only one average student age.

5. Study Perspectives

It would be interesting to link technological with physical aspects (i.e., running at high intensity, distance covered, number of sprints, etc.) in future original investigations employing the Global Positioning System (GPS) instead of polars. Additionally, by emphasizing the impact of verbal support on students’ tactical abilities during small-sided soccer games, these types of studies should be generalized for the various age groups.

Another interesting point would be relating these responses with psychological aspects, such as mood state and physical enjoyment, since these aspects are important variables of physical engagement. These factors should be checked for future studies.

6. Conclusions

The results of this research confirm that teacher verbal encouragement enhances adolescent female student’s performance on physical fitness tests as well as their physiological reactions and technical competence during school-level small-sided soccer matches. The results show that verbal encouragement is a constructive method to improve female adolescent performance during SSG and could be a practical method to improve the quality of the training process by allowing better physiological adaptations. These results could inform physical education teachers of the usefulness of verbal encouragement in the teaching-learning process in the school setting. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to better support this exploratory recommendation in an evidence-based and data-driven manner.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.H., M.G., O.S. and D.I.A.; methodology, M.A.H., O.S., M.G., H.G. and F.S.; validation, M.A.H., O.G. and M.G.; formal analysis, M.A.H., M.G., O.S., F.S., H.G. and O.A.S.; investigation, M.A.H. and O.S.; data curation, M.A.H., O.A.S. and H.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.H., M.G., O.S., F.S. and H.G.; writing—review and editing, M.A.H., M.G., O.S., F.S., H.G. and D.I.A.; visualization, M.A.H., O.G. and O.S.; supervision, O.S. and D.I.A.; funding acquisition, M.A.M. and D.I.A.; project administration, M.A.H., M.G., O.S., F.S. and H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

APC (article processing charge) was funded by the University of Oradea through an internal project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the research ethics committee of the High Institute of Sports and Physical Education of Kef, Tunisia (approval no. 022/2022 and date of approval 20 April 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our warmest gratitude to all those who contributed to this study. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the University of Oradea, which supported the APC. We would especially like to thank the director of the school who gave us permission to carry out this experiment, and last but not least, thank you to the students and their teachers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ellliot, A.J.; Covington, M. Approach and Avoidance Motivation. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 13, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schunk, D.H. Self-efficacy, motivation, and performance. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 1995, 7, 112–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicaise, V.; Cogérino, G.; Bois, J.; Amorose, A. Students’ perceptions of teacher feedback and physical competence in physical education classes: Gender effects. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2006, 25, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, C.M.; Ruiz-Eugenio, L.; Redondo-Sama, G.; Villarejo-Carballido, B. A new application of social impact in social media for overcoming fake news in health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, J.A.; Hutchinson, N.T.; Powers, S.K.; Roberts, W.O.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Radak, Z.; Berkes, I.; Boros, A.; Boldogh, I.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and physical activity. Sports Med. Health. Sci. 2020, 2, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekinari, A. Verbal Aggressiveness and Leadership Style of Sports Instructors and Their Relationship with Athletes’ Intrisic Motivation. J. Creat. Educ. 2014, 5, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halperin, I.; Pyne, D.B.; Martin, D.T. Threats to internal validity in exercise science: A review of overlooked confounding variables. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015, 10, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription 9th Ed. 2014. J. Can. Chiropr. Assoc. 2014, 58, 328. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Fernandez, J.; Sanz-Rivas, D.; Mendez-Villanueva, A. A review of the activity profile and physiological demands of tennis match play. Strength Cond. J. 2009, 31, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilit, B.; Senel, Ö.; Arslan, E.; Can, S. Physiological responses and match characteristics in professional tennis players during a one-hour simulated tennis match. J. Hum. Kinet. 2016, 51, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, M.; Elvers, S. Elite youth soccer players’ physiological responses, time-motion characteristics, and game performance in 4 vs. 4 small-sided games. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 2652–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selmi, O.; Khalifa, W.B.; Ouerghi, N.; Amara, F.; Zouaoui, M.; Bouassida, A. Effect of verbal coach encouragement on small sided games intensity and perceived enjoyment in youth soccer players. J. Athl. Enhanc. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampinini, E.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Castagna, C.; Abt, G.; Chamari, K.; Sassi, A.; Marcora, S.M. Factors influencing physiological responses to small-sided soccer games. J. Sports Sci. 2007, 25, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, F.A.; Faude, O.; Kölling, S.; Kellmann, M.; Donath, L. Verbal encouragement and between-day reliability during high-intensity functional strength and endurance performance testing. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilit, B.; Arslan, E.; Akca, F.; Aras, D.; Soylu, Y.; Clemente, F.M.; Knechtle, B. Effect of Coach Encouragement on the Psychophysiological and Performance Responses of Young Tennis Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahli, H.; Selmi, O.; Zghibi, M.; Hill, L.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B.; Clemente, F.M. Effect of the verbal encouragement on psychophysiological and affective responses during small-sided games. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rube, N.; Secher, N.H. Paradoxical influence of encouragement on muscle fatigue. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1981, 46, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, J.; Garcia, G.; Macas, V.; Ibanez, S.; Abrantes, C.; Caixinha, P. Heart rate and perceptual responses to 2 × 2 and 3 × 3 small-sided youth soccer games. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2007, 6, 121–122. [Google Scholar]

- Feten, S.; Hammami, R.; Sahli, H.; Jebabli, N.; Selmi, W.; Zghibi, M.; van den Tillaar, R. The Effects of Combined Verbal Encouragement and Technical Instruction on Technical Skills and Psychophysiological Responses during Small-Sided Handball Games Exercise in Physical Education. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 902088. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. How to randomize. BMJ 1999, 319, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallerand, R.J. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in sport. In Encyclopedia of Applied Psychology; Spielberger, C., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durnin, J.V.; Webster, C.I. A New Method of Assessing Fatness and Desirable Weight for Use in the Armed Service Army Department; Technical Report; Ministry of Defense: Arlington, VA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, J.M. Growth endocrinology of the adolescent. In Endocrine Genetic Diseases of Childhood and Adolescence; Gardner, L., Ed.; W. B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Chamari, K.; Chaouachi, A.; Hambli, M.; Kaouech, F.; Wisløff, U.; Castagna, C. The five-jump test for distance as a field test to assess lower limb explosive power in soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krustrup, P.; Mohr, M.; Amstrup, T.; Rysgaard, T.; Johansen, J.; Steensberg, A.; Pedersen, P.K.; Bangsbo, J. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test:Physiological response, reliability, and validity. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2003, 35, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauole, K.; Madole, K.; Garhammer, J.; Lacourse, M.; Rozenek, R. Reliability and Validity of the T-Test as a Measure of Agility, Leg Power, and Leg Speed in College-Aged Men and Women. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2000, 14, 443–450. [Google Scholar]

- Bujalance-Moreno, P.; Latorre-Román, P.Á.; García-Pinillos, F. A systematic review on small-sided games in football players: Acute and chronic adaptations. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 921–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selmi, O.; Ouergui, I.; Levitt, D.E.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Knechtle, B.; Bouassida, A. Small-Sided Games are More Enjoyable Than High-Intensity Interval Training of Similar Exercise Intensity in Soccer. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2020, 11, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, O.; Gonçalves, B.; Ouergui, I.; Levitt, D.E.; Sampaio, J.; Bouassida, A. Influence of well-being indices and recovery state on the technical and physiological aspects of play during small-sided games. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 2802–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.; Batterham, A.; Hanin, J. Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2009, 41, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreacci, J.L.; Lemura, L.M.; Cohen, S.L.; Urbansky, E.A.; Chelland, S.A.; Duvillard, S.P.V. The effects of frequency of encouragement on performance during maximal exercise testing. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Derakhshan, A.; Zhang, L. Researching and Practicing Positive Psychology in Second/Foreign Language Learning and Teaching: The Past, Current Status and Future Directions. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 731721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickers, M.J. Does verbal encouragement work? The effect of verbal encouragement on a muscular endurance task. Clin. Rehabil. 1993, 7, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.M.; Dutton-Challis, L.; Cottrell, D.; Guy, J.H.; Hettinga, F.J. Impact of active and passive social facilitation on self-paced endurance and sprint exercise: Encouragement augments performance and motivation to exercise. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Pugsley, S.O.; Sullivan, M.J.; Thompson, P.J.; Berman, L.; Jones, N.L.; Fallen, E.L.; Taylor, D.W. Effect of encouragement on walking test performance. Thorax 1984, 39, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, A.B.; Farinon, R.L.; Perasol, D.M.; dos Santos, J.M.; de Freitas, V.H. Influência de estímulosmotivacionais no desempenhoem testes de salto vertical de atletas de futsal sub-17. Rev. Educ. Esporte 2020, 34, 727–733. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.; Jeon, S.; Kang, M.; Song, J.S.; Ye, X. Does Performance-Related Information Augment the Maximal Isometric Force in the Elbow Flexors? Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2021, 46, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Shin, J.; Kim, D.; Park, J. Effect of verbal encouragement on quadriceps and knee joint function during three sets of knee extension exercise. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2021, 29, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkhiria, C.; de Marco, G.; Driss, T. Effects of verbal encouragement on force and electromyographic activations during exercise. J. Sport. Med. Phys. Fit. 2018, 58, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, R.; Nebigh, A.; Selmi, M.A.; Rebai, H.; Versic, S.; Drid, P.; Jezdimirovic, T.; Sekulic, D. Acute Effects of Verbal Encouragement and Listening to Preferred Music on Maximal Repeated Change-of-Direction Performance in Adolescent Elite Basketball Players—Preliminary Report. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, J.E.; Lago, C.; Gonçalves, B.; Maçãs, V.M.; Leite, N. Effects of pacing, status and unbalance in time motion variables, heart rate and tactical behaviour when playing 5-a-side football small-sided games. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2014, 17, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli, H.; Haddad, M.; Jebabli, N.; Sahli, F.; Ouergui, I.; Ouerghi, N.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Zghibi, M. The effects of verbal encouragement and compliments on physical performance and psychophysiological responses during the repeated change of direction sprint test. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 698673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacono, A.D.; Ardigò, L.P.; Meckel, Y.; Padulo, J. Effect of small-sided games and repeated shuffle sprint training on physical performance in elite handball players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellal, A.; Owen, A.; Wong, D.; Krustrup, P.; Van Exsel, M.; Mallo, J. Technical and physical demands of small vs. large sided games in relation to playing position in elite soccer. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2012, 31, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halouani, J.; Chtourou, H.; Gabbett, T.; Chaouachi, A.; Chamari, K. Small-sided games in team sports training: A brief review. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 3594–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente, F.M.; Afonso, J.; Castillo, D.; Los Arcos, A.; Silva, A.F.; Sarmento, H. The effects of small-sided soccer games on tactical behavior and collective dynamics: A systematic review. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 134, 109710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Drust, B. Physiological and technical demands of 4 v 4 and 8 v 8 in elite youth soccer players. Kinesiology 2007, 39, 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Práxedes, A.; Moreno, A.; Sevil, J.; García-González, L.; Del Villar, F. A preliminary study of the effects of a comprehensive teaching program, based on questioning, to improve tactical actions in young footballers. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2016, 122, 742–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulds, S.J.; Hoffmann, S.M.; Hinck, K.; Carson, F. The coach–athlete relationship in strength and conditioning: High performance athletes’ perceptions. Sports 2019, 7, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teques, P.; Duarte, D.; Viana, J. Coaches’ emotional intelligence and reactive behaviors in soccer matches: Mediating effects of coach efficacy beliefs. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-García, J.; Pulido, J.J.; Ponce-Bordón, J.C.; Cano-Prado, C.; LópezGajardo, M.Á.; García-Calvo, T. Coach encouragement during soccer practices can influence players’ mental and physical loads. J. Hum. Kinet. 2021, 79, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigueros, R.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; López-Liria, R.; Rocamora, P. The dark side of the self-determination theory and its influence on the emotional and cognitive processes of students in physical education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Calvo, T.; Leo, F.M.; Gonzalez-Ponce, I.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Mouratidis, A.; Ntoumanis, N. Perceived coach-created and peer created motivational climates and their associations with team cohesion and athlete satisfaction: Evidence from a longitudinal study. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1738–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).