1. Introduction

Social trust is important for modern state systems and social stability in both developed and developing countries, and trust can be effective in increasing investment rates and promoting economic development (According to scholars, social trust is mainly defined as follows: sometimes trust in someone comes from one’s own intuition, which is often referred to as trust based on personality traits [

1], sometimes it comes from emotion or identification, such as with relatives, friends, classmates, etc. [

2,

3,

4], and also sometimes based on adequate information and decisions made by rational economists, such as insurance brokers, real estate brokers, etc. [

4,

5,

6], and more often will be based on institutional trust, such as trust in the government, military, hospitals, etc. [

7,

8,

9]. In this paper, we chose the second one, i.e., social trust being derived from emotions or identity, such as trust arising from people such as relatives, friends, and classmates) [

10]. Since the beginning of the modern era, trust issues have become more pronounced worldwide. The public’s social trust is declining year by year. Researchers want to determine the root causes of the decline in trust to improve the current situation [

11]. Social trust refers to the development of generalized trust in others, forming emotional attachment, and making some behavioral decisions for the sake of certain specific groups of people as a form of social capital [

12] Social trust can be influenced by various factors such as individual factors, cultural factors, institutional factors, and association factors [

13]. However, some studies have shown that the modern media’s negative government coverage significantly reduces public confidence in government [

14,

15], and the electronic media’s promotion of the “mean world” can undermine social trust [

16,

17].

While emphasizing economic development, China has neglected some social conflicts and consequently experienced a social trust crisis much like other countries [

18,

19,

20]. This has further decreased trust in local government as a factor affecting political stability, although public trust levels in the central government are high [

21,

22].

In China, the Internet is a critical medium to evaluate. By December 2021, China had 1.032 billion Internet users, up by 42.96 million from December 2020, with an Internet penetration rate of 73.0% and 28.5 h of Internet access per capita per week, according to the Statistical Report on Internet Development in China. The public, including rural residents, increasingly search and access information online for decision-making [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Currently, the Internet affects all corners of social life and more profoundly impacts public social trust [

30].

Scholars have studied social trust and changes in social values, social trust crisis causes, and the differences in the degree of social trust among populations [

18,

31,

32,

33], but few have analyzed the perspective of technological progress in modern society. With the advent of the Internet era, rural residents have been exposed to more and more social networking tools that can rapidly disseminate news and even do so in real time [

34,

35,

36]. Due to information asymmetry and the lack of mutual trust between local government and rural residents, conflicts break out between them in various scenarios such as land acquisition compensation and wage claims, which then become vicious mass incidents [

37]. Such incidents are highly susceptible to mass Internet dissemination, triggering further conflicts [

38]. Furthermore, the Internet affects people’s social trust level [

39]. Modern societal life has been largely affected by the influx of large amounts of information across different mediums, and the social trust issue poses a major challenge for governance [

18,

30,

40,

41].

Evidence suggests that good rural governance practices influence rural residents’ attitudes and behaviors toward the government, and empowering rural governance through digitization and intelligence can help capture public opinion [

42,

43]. However, the role of contextual determinants, such as the coexistence of old and new media and population differences, remains under-explored in the existing research on information access and social trust. Therefore, in the context of digital rural governance, it became necessary for this study to explore rural residents’ social trust using information access.

2. Current Status of Digitalization and Internet Use in Rural China

According to the 49th Statistical Report on Internet Development in China released by the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), as of December 2021 the number of rural Internet users in China was 284 million, accounting for 27.6% of all Internet users. The Internet penetration rate in rural areas was 57.6%, 1.7 percentage points higher than that in December 2020. The difference in the Internet penetration rate between urban and rural areas narrowed by 0.2 percentage points compared with that in December 2020. The difference between urban and rural areas narrowed by 0.2 percentage points compared with December 2020.

The report points out that the new Internet industry and new modes continue to enhance the connectivity function in rural areas, and good progress has been made in the construction of the digital countryside. First, digitalization promotes the integrated development of urban and rural areas. In terms of new digital infrastructure, China’s existing administrative villages have fully realized the idea of “village broadband”, and the problems of communication difficulties in poor areas have been resolved. In terms of industrial digitalization, the integration of the digital economy and real industry is accelerating, the level of intelligent manufacturing is steadily improving, and the digital transformation of rural areas is continuously being promoted, giving rise to a large number of new business models. In terms of digital industrialization, new breakthroughs have been made in key core technologies, data has become a key element in promoting economic development, and the contribution of digital industries such as 5G, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and e-commerce to urban and rural development is increasing. Second, the construction of an intelligent green countryside is steadily advancing. The application area of agricultural and rural big-data systems is increasing, and since the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs government information resource sharing platform has been online and running, through data integration and sharing, the annual access to the platform has exceeded by 50 million times. Digital technology such as the Internet has a prominent role to play in the smart green countryside. Through information technology, a series of platforms including habitat environments, soil erosion dynamics, and rural river and lake management have been gradually built, and the intelligent green information system involving the construction of a rural ecological environment has been further improved. Third, rural science and technology innovation has reached a new level. Relying on the national key R&D program projects, various regions have accelerated the research and development of basic frontiers, key technologies and their application and demonstration, and promoted the deep integration of agricultural and rural construction and digital development. They have attracted, coalesced, and cultivated a large number of outstanding agricultural science and technology talents, effectively constructed talent echelons and innovation teams to support the development of industries and disciplines, and improved China’s agricultural science and technology innovation capacity.

As the new generation of information revolution, mainly the Internet and mobile Internet, has surged forward, it has not only affected the life of urban residents but also the life of rural residents. As the economic and social structure of rural areas has changed very much, the needs of rural residents are also changing day by day, which to a certain extent requires rural governance to be upgraded to a modern level. Empowering rural governance through intelligence and digitalization can provide scientific support for rural governance decision-making on the one hand and open up new thinking for rural governance modernization on the other. Empowering rural governance through digitalization and intelligence can not only effectively promote the development of local economy but also enhance the happiness of rural residents and make rural life more harmonious and orderly. Rural residents can use the Internet to pay bills, patrol for safety, social security, and medical insurance, and purchase goods without leaving home, and they can also sell local specialties and promote tourism through live streaming and e-commerce, which really facilitates the lives of many elderly people and children left behind. Digital and intelligent empowerment of rural governance has been carried out nationwide, promoting good governance at the grassroots level in the countryside and providing a scientific guarantee for rural revitalization.

3. Analytical Framework and Research Hypotheses

Many scholars have explored the issue of trust from different perspectives, but in recent years, researchers have mostly focused on trust in the context of social capital theory [

44]. Trust is seen as an important aspect of social capital, and social trust as a category emerges from this, in the narrow sense that social trust is actually trust as a central dimension of social capital [

12]. Coleman explained the issue of trust based on rational choice theory in Foundations of Social Theory, where he argued that trust is a rational behavior under risk conditions and that trust is also a kind of social capital [

45]. With the expansion of the influence of modern media, the media has gradually acted as an intermediary in trust relationships in society, and the processing and interpretation of information by modern media can greatly influence people’s judgment and affect public trust [

45]. Some argue that modern media such as newspapers, television, and the Internet has facilitated the transmission of information and influenced people’s social trust as an important socialization mechanism [

16,

17,

46,

47,

48,

49].

Rural residents tend to search for information through various channels to eliminate information asymmetry and achieve optimal decision-making [

50]. The more transparent the Internet environment, the more open space it provides for public opinion, which can eliminate information asymmetry and achieve a democratic distribution of speech [

51]. Due to social learning, both original news content and Internet users’ comments on the news can significantly impact users’ decisions [

52]. Due to the limited screening ability and screening cost of rural residents, a lot of true and false news may be accessed and absorbed by rural residents, which impacts their social trust [

53]. Possible reasons include differences in news dissemination on the Internet versus television and the fact that more fake news may be disseminated on the Internet, which affects behavior and social trust among rural residents, known as irrational behavior, as described in behavioral economics [

54].

One scholar pointed out that many scholars have debated whether the communication effect of new online media is positive or negative but failed to reach a consensus [

3]. According to behavioral economics and the “propaganda to persuade” theory, some believe that the mainstream values of media propaganda are still accepted by people, and the media can mobilize the audience to agree with the political and economic policies of national reform, which positively impact social and political stability. Similar to Wang, this study considered the view that the current media advocacy and education reinforce the “media propaganda and mobilization effect.” Furthermore, it accepted the view that the current media propaganda and education are ineffective/counterproductive due to the “boomerang effect of media propaganda” (The boomerang effect of propaganda was first presented by Merton et al. in their discussion of early radio and film propaganda and was used to refer to the ineffectiveness or negative effectiveness of radio and film propaganda [

3,

30,

55]. Therefore, on the one hand, online public opinion can expand horizons, increase the frequency of social interactions, and enhance trust; on the other hand, online public opinion increases suspicion and indifference among strangers brought by negatively oriented news and intensifies the negative impact on people’s social trust [

56]. This study proposed the following research question based on the mechanism of the influence of information access on rural residents’ social trust: rural residents’ social trust is affected by the way they access information due to the “media propaganda and mobilization effect” and the “boomerang effect of media propaganda.”

Studies on the impact of different media types on social trust show that modern media as a source of information and the level of public social trust are closely related, such as Robinson’s study on television, Brehm and Rehn’s study on newspapers, and Best and Krueger’s study on new media on the Internet. To avoid the bias brought by studying a single mode of information access, this study examined the impact of rural residents’ use of both information access methods on social trust [

15,

57,

58].

Hypothesis 1. The frequency of Internet use has a significant positive effect on rural residents’ social trust.

Hypothesis 2. The frequency of TV use has a significant positive effect on rural residents’ social trust.

In the information era, the Internet has gradually begun to spread, penetrate, and expand to rural areas, but due to differences in usage inertia and economic conditions, there will remain a situation in the majority of rural areas where old and new media coexist for quite some time. Whenever a new media form emerges, the topic of competition between the “new” and “old” media is debated. The competition between the Internet and traditional media focuses on grabbing audience resources. The Internet has squeezed people’s time to use traditional media, and there may be a substitution effect between different information access modes such as traditional media and the Internet [

59]. The substitution effect describes the pattern of competition between media forms. Scholars have studied whether there is a substitution effect between media forms but have not reached a unanimous conclusion. Some found that Internet use motivates people to read newspapers and listen to the radio more often [

60,

61,

62,

63]. Therefore, the substitution effect between media forms may not only be an “increase–decrease” relationship, but also an “increase–increase” relationship.

Meanwhile, according to the Statistical Report on the Development Status of China’s Internet, although the Internet penetration rate in China reached 71.6% as of June 2021, it was less than 60% in rural areas, and the rate varied widely in different rural areas. Based on this, much research has been conducted on the fairness of information supply, but the arguments of various scholars have not reached a consensus. Due to historical institutional barriers and rapid social changes, there are still obvious traces of economic structures in the different regions of rural China, and the resulting regional development disparities will inevitably lead to differences in the social environment in which rural residents with different characteristics live. This also implies that there are inevitable differences in the Internet public resources available to people of different genders, educational levels, ages, and regions, and that there is a phenomenon of differentiation [

64]. Zhang similarly points out that there are inequities in government public information services between urban and rural areas regions and social groups, and there is the existence of some information-disadvantaged groups who cannot access information through the Internet or television [

65]. Due to the lack of public information and information asymmetry, it is difficult for information-disadvantaged rural residents to be competitive in accessing public services. Access and usage disparities are the main influencing factors of the “digital divide” [

66], and usage disparities are another prominent factor in the exacerbation of the digital divide due to the different levels of Internet development in different regions [

67,

68]. Because of the “digital divide” phenomenon, rural residents may increase their use of one media based on substitution effects due to inadequate or limited access to information in another media. To investigate the true relationship between different information access modes and their impact on rural residents’ social trust, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 3. When the use of the Internet and TV is insufficient or limited, there is a substitution effect of the two information access modes on the social trust of rural residents.

4. Data, Variables, and Model

4.1. Data Sources

The China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) is a large-scale micro household survey conducted by the China Social Science Survey Center (ISSS) of Peking University with the participation of several top universities and academic institutions in China. It is a nationwide, comprehensive social tracking survey project aiming to reflect the social, economic, demographic, educational, and health changes in China by tracking and collecting data at three levels, namely the individual, household, and community levels, with a target sample size of 16,000 households in 25 provinces/cities/autonomous regions. It provides a data base for academic and policy research. Among the existing social research databases, the survey work of this database has a high national representation and authority. Data source:

http://www.isss.pku.edu.cn/cfps/download/i-ndex#/fileTreeList (accessed on 27 December 2022).

The data used in this study were obtained from the CFPS 2018 adult questionnaire database with a total sample size of 37,354. After excluding samples with missing values, data from 12,042 rural residents (living in rural areas) and 12,498 urban residents (living in cities and towns) were included. Meanwhile, to examine the robustness of the effects of Internet and television use on rural residents’ social trust and to exclude the possible reverse causality between them, we combined and collated the data of rural residents in 2014 and 2018 and selected 8602 common samples for the robustness test (Approximately 50% of the samples in CPFS 2016 had missing data for using the Internet to access news. To avoid research bias, data from CFPS 2014 were selected for the study).

In order to study the heterogeneity of the population with different characteristics, 12,042 samples of rural residents were classified, including 5962 samples of females and 6080 samples of males, to study the differences between samples of different genders. The samples were classified by age, including 4582 samples of young people aged less than 45 years old and 7460 samples of older people aged more than 45 years old, to study the differences between samples of different age. Out of the total samples, 3707 were illiterate/semi-literate and 8335 were educated at elementary school and above, and these data were used to study the differences among different education levels; 4087 were from eastern China and 7955 samples were from central and western China, and these data were used to study the differences among different regions.

4.2. Variable Selection

We classified the variables involved into the following three categories, and their definitions are shown in

Table 1.

4.2.1. Explained Variable

The explained variable used in this study was social trust evaluation. The traditional quantitative indicators such as GDP, basic investment, and education investment are relatively one-sided when evaluating economic and social development. Two types of social trust research data were selected from the CFPS 2018 as social trust evaluation indicators for rural residents. One was social trust in others, and the question “, do you think most people can be trusted, or should you be more careful with people?” was chosen. Respondents chose 1 if their answer was “Most people can be trusted” and 0 if their answer was “Be as careful as possible” [

51]. The other was trust in different groups of people. The trust questions in the CFPS for the five groups of people were “How much do you trust your parents/neighbors/cadres/doctors/strangers?” The Likert scale was used to classify the social trust evaluation results into 11 levels, with 0 meaning

very distrustful and 10 meaning

very trustful, and the respondents’ responses were used as actual values (“Cadre” means a local county/county city/district government official.).

4.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

The core explanatory variable in this study was how information is accessed. Two core explanatory variables, Internet use and television use, were chosen to represent the impact of old and new media. The CFPS question on Internet use to access news was “How many days in the past week did you learn about politics through online news?” Respondents’ answers were selected as the actual values taken. Additionally, traditional media impact residents’ behavioral decisions. Therefore, “How many days in the past week did you learn about political information through television news” was selected as the explanatory variable for traditional media.

4.2.3. Control Variables

Social trust is susceptible to factors such as social individual characteristics, political orientation, social capital, and objective circumstances [

13,

32,

33,

51,

53,

56,

69,

70]. Therefore, this study established control variables in the following four aspects: (1) Due to the objective existence of individual differences, the individual characteristics of respondents can significantly impact social trust evaluations according to the above discussion. Variables such as gender, age, marital status, ethnicity, education level, health status, work status, and living status were selected as measures of respondents’ characteristics, among which “how happy I feel” was selected for living status, with 0 representing the lowest and 10 representing the highest, and the actual score was chosen as the variable value. (2) Participation in political groups was selected as a measure of an individual’s propensity for political participation. This was measured by the CFPS question “Which of the following organizations are you currently a member of, including the Communist Party of China (CPC), democratic parties, people’s congresses (deputies) at or above the county/district and county/district levels, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) (members) at or above the county/district and county/district levels, labor unions, the Communist Youth League, the Women’s Federation, the Federation of Industry and Commerce, informal associations (community, network, salon, etc.), religious/faith groups, private business owners’ associations, and individual workers’ associations?” This was a multiple-choice question, and the total number of political groups in which the respondents were involved was chosen as the value [

71]. (3) Individual social capital also affects social trust. The question “How well connected” was selected, with 0 representing the lowest and 10 representing the highest. (4) Considering that respondents were susceptible to the economic and social development of their regions, two variables, such as urban and rural areas and regions, were chosen to measure this difference. The economic and social differences between urban and rural areas are relatively large. Whether the respondent lived in an urban or rural area was used as an indicator to measure the living environment. Due to the correlation between online information accessed by residents and economic development in the east, central, and western regions of China, “region” was mainly used as a dummy variable to exclude regional variability in respondents’ social trust [

33,

72].

4.3. Descriptive Analysis

4.3.1. Descriptive Statistics for the Sample’s Internet and Television Use

Rural residents did not have equal access to information, as shown in

Table 2. A total of 6256 samples, or 51.96%, accessed news through television. Specifically, 2656 samples, or 22.06%, accessed news this way 7 days a week, indicating that traditional media remained the main source of information for rural residents. A total of 3679 samples, or 40.37%, accessed news through the Internet. Specifically, 1662 samples, or 13.8%, used the Internet 7 days a week, showing that its new media was an important information source. There were 2577 more people who never used the Internet for news compared to those who did not watch television for news, and there were 994 more people who watched television every day than those who used the Internet every day, that is, more people received news from television.

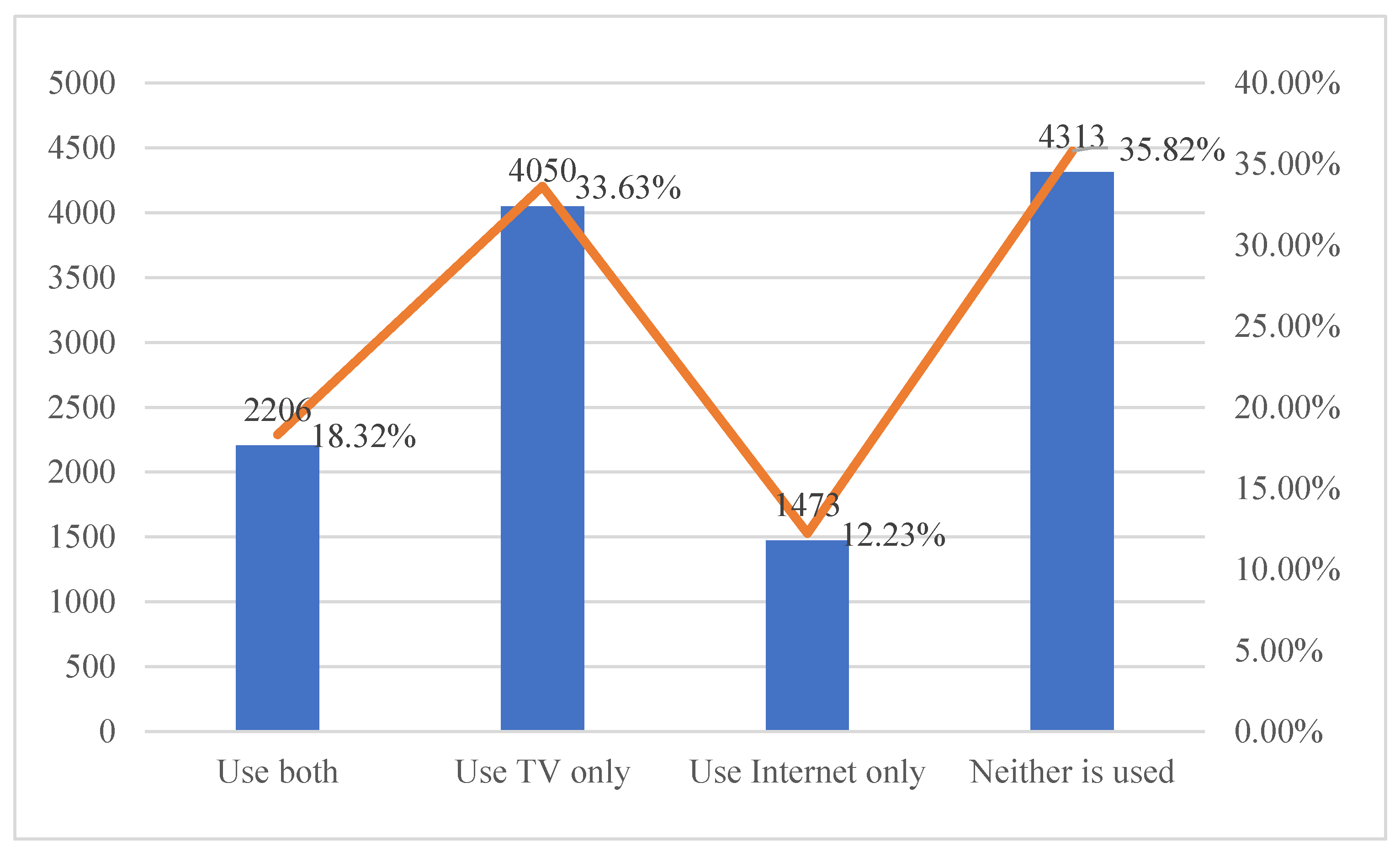

A further television and Internet use analysis is shown in

Figure 1. A total of 2206 samples, or 18.32%, used both television and the Internet to receive news; the number of samples using only television or the Internet was 4050 and 1473, respectively; 4313 samples, or 35.82%, used neither television nor the Internet.

4.3.2. Descriptive Statistics of Social Trust

As seen in

Figure 2, the results showed that 6477 residents (53.79%) trusted others, and 5565 (46.21%) felt that others could not be trusted. Further, 7296 (58.56%) urban residents trusted others, which was higher than rural residents (53.79%); statistically speaking, urban residents trusted others more than rural residents [

73]. The percentage of trust in others among rural residents was 5.74% higher in men than women, significantly higher in young people than that of middle-aged and elderly people, higher in people with elementary school education or above than that of illiterate/semi-literate people, and similar among people in eastern, central, and western regions. The percentage of trust and distrust in others among women and illiterate/semi-literate people were basically equal.

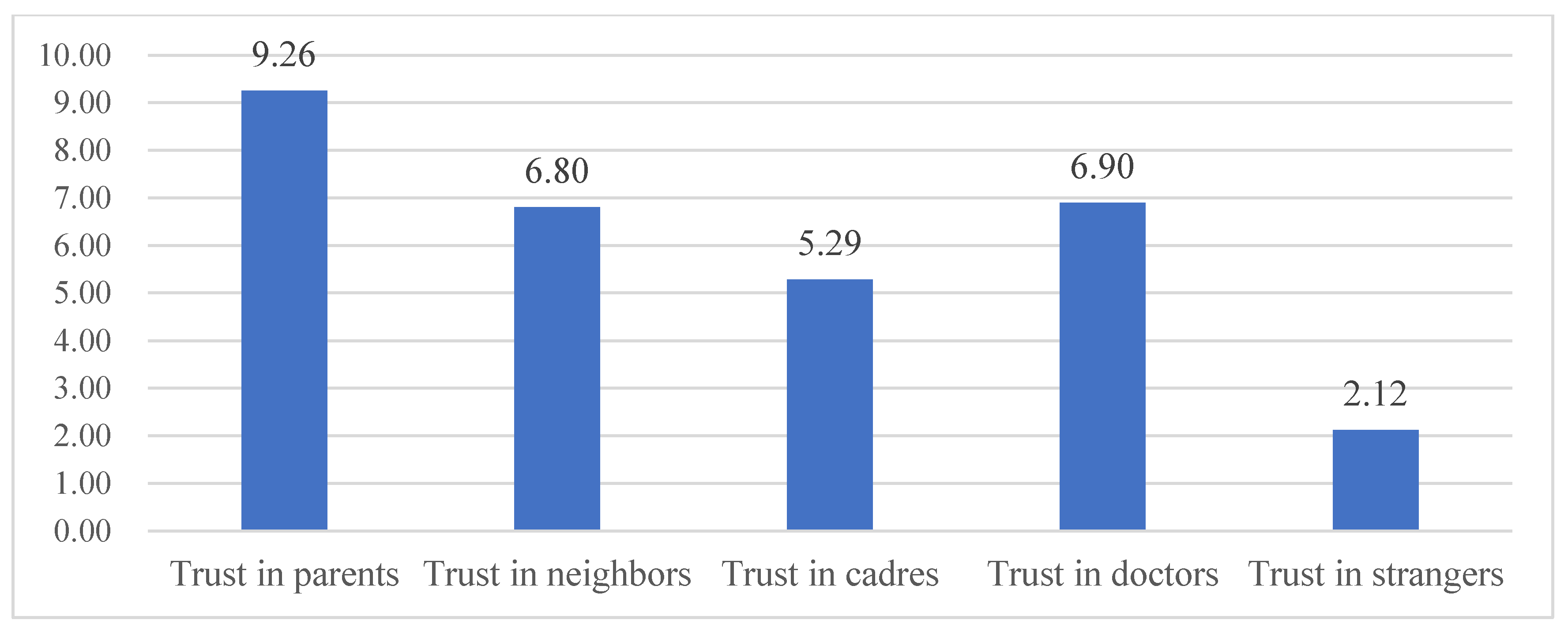

As Chinese people’s trust is based on a community of blood relations, rural residents showed an ordered pattern of affinity in social trust [

13]. In order to study the social trust characteristics of rural residents, a descriptive analysis of rural residents’ trust in different groups of people was conducted. As can be seen from

Figure 3, the most trusted group of rural residents was parents, followed by doctors, neighbors, and cadres, and the least trusted was strangers.

4.4. Model Construction

4.4.1. Probit Model

The probability of whether rural residents trust others in the process of generating social trust is a binary choice [

24]. The decision relies on the way rural residents obtain information and the individual characteristics of rural residents. Therefore, the Probit model was used to investigate the effects of these factors on rural residents’ social trust. Assuming a standard normal probability distribution of social trust among rural residents, Equation (1) was obtained:

where

represents rural residents’ social trust and is a binary discrete variable, with a value of 1 indicating trust in others and a value of 0 indicating distrust in others.

includes core influences such as the use of the Internet for news and the use of television for news that affect rural residents’ social trust.

4.4.2. Propensity Score Matching (PSM) Method

This study adopted the PSM method proposed by Rosenbaum and Rubin, which is an approximate natural experiment method that can effectively overcome the error and endogeneity problems caused by sample selection bias [

74]. After observation of the samples, rural residents were divided into treated and control groups according to whether they used the Internet or television to obtain news. Then, the two sample groups were matched one by one according to the matching principle so that the characteristics of the two groups could be as similar as possible. This allowed the control group to simulate the counterfactual state (no Internet or television use) of the treated group and thus compare the differences in rural residents’ social trust in these two contrasting situations of Internet or television use and no Internet or television use.

First, the Probit model was used to screen the variables that affected rural residents’ social trust other than Internet or television use, and then the main variables that affected rural residents’ social trust were selected, and the conditional probability—propensity score (

PS value)—was calculated using the model:

where

denotes Internet or television use,

denotes no Internet or television use, and

denotes the observable characteristics of rural residents in the treated (matched variables).

where

denotes the cumulative distribution function of the logistic distribution,

is a vector of a set of farm household characteristics that may affect the identification of a farm household as poor, and

is the corresponding parameter vector. After obtaining the parameter estimate from Equation (4), the probability

that each farm household would be identified as poor, which was the PS value of each farm household, could be calculated. For the

th farm household, the propensity score was

, and the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) was:

where

and

indicate trust in others in the case of the

th rural resident using the Internet or television or not using the Internet or television, respectively.

The three matching methods used to obtain the ATT were nearest-neighbor matching, radius matching, and kernel matching.

After the matching was completed, the

ATT could be further calculated. For the

th observation value in the treated group, that is,

, assuming it had

matches, the weight was set to

if

, and otherwise it was set to

. Assuming a total of

observed objects in the treated group, the

ATT was estimated as:

where M denotes the matching method (nearest-neighbor matching or radius matching), with the weight of

.

For kernel matching, the

ATT was estimated as:

where

is the kernel function, and

is the bandwidth parameter. As it is not possible to derive a specific expression for the standard error of

in the above equation, the bootstrap method is commonly used in the literature to obtain the standard error of

, and this method was used in this study as well.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Baseline Results

The impact of information access modes on rural residents’ social trust was analyzed using Stata 16.0, and the final regression results are shown in

Table 3. Columns (1) and (2) show that both the Internet and television had a significant positive effect on social trust. Column (3) shows that after two explanatory variables were added, the coefficients of both variables were significantly positive, indicating that either the Internet or television had a significant positive effect on rural residents’ social trust. Finally, control variables were added. Although the coefficients of the Internet and television became smaller, they were still positive and significant, as shown in column (4).

The primary concern of this study pertained to the effect of information access on social trust. According to the regression results of Equation (4), the influence coefficient of the Internet was positive at 0.0206 and significant at the 1% significance level, indicating that rural residents who used the Internet to receive news had increased social trust in the news, and each additional day of Internet use increased trust in others by 2.06%, validating Hypothesis 1. The influence coefficient of television was positive at 0.0140 and significant at the 1% significance level, indicating that rural residents who used television for news had increased social trust compared to those who did not use television for news, that is, trust in others increased by 1.40%, validating Hypothesis 2, which was consistent with Wang’s study [

13].

Table 3 shows that the influence coefficient of gender was 0.0546 and that men had higher social trust in others compared to women. The influence coefficient of the age variable was positive, indicating that older people were more trusting of others than younger people. Married individuals had lower trust in others than those without spouses. The effect of the ethnicity variable was not significant. More educated rural residents had higher social trust in others. Unhealthy people in rural areas had lower trust in others than healthy people. The influence coefficient of work status was negative, and rural residents who had a job had lower social trust in others than those who did not. The influence coefficient of living conditions was significant and positive, indicating that rural residents’ social trust in others varied by living standards, and those who had good living conditions had higher trust in others. The influence coefficient of participation in organizations was not significant, indicating that participation in organizations had no significant effect on rural residents’ trust in others even though participation in organizations expands networks. The influence coefficient of social capital was significant and positive, indicating that rural residents who were popular with others and liked to make friends had higher social trust in others. The influence coefficient of the central and western regions was not significant, indicating that the difference in social trust was not significant between rural residents in the central and western regions and those in the eastern region.

5.2. Robustness Test

Based on Lian, the following forms were selected in this subsection to perform robustness tests. The first was the proxy variable regression method. In the baseline regression, although we found a significant effect of information access on rural residents’ social trust, we did not rule out the possibility of reverse causality between them [

75]. Referring to Huang et al. and Qian, a history of Internet use and television use among rural residents was used to ensure information access preceded social trust evaluation [

76,

77]. Thus, this subsection combined and collated data of rural residents from 2014 and 2018 and selected a common sample totaling 8602. The regression was run through a Probit model with the core explanatory variable being rural residents’ use of the Internet and television for news in 2014 and the explanatory variable being rural residents’ social trust in 2018, and the regression results are presented in model (1) in

Table 4. The second was the varying sample size method. A summary of the sample data revealed less Internet use among those aged 70 years and older, potentially leading to a biased study. In this subsection, referring to Chen and Ju, those over 70 years were excluded, the regression analysis of how information access affected social trust was re-analyzed by the Probit model, and the regression results are shown in model (2) [

78,

79]. The third was the model replacement method. Referring to the studies by Mood, Wooldridge, Karlson et al., Hong, a linear probability model (LPM) was used to perform the robustness test, and the regression results are shown in model (3) (Referring to the studies of scholars such as Mood and Hong, the linear probability model (LPM) can be used as a complementary test to the Logit and Probit models, but is less often used directly in empirical studies because of the shortcomings of the LPM’s own model setup [

80,

81,

82,

83]. The fourth method was used to replace the explained variable. The value of rural residents’ trust in their parents, neighbors, cadres, doctors, and strangers was added as the new explained variable. See model (4) for the regression results. As can be seen in

Table 4, although there were differences in the values of the influence coefficients, the effects of Internet and television use to access news on social trust were both significant and positive, indicating the robustness of the regression results (The results of many control variables are not shown in

Table 4 to save space. Please ask the author for a copy, if desired. Similarly, the other tables in this paper are handled similarly and will not be repeated).

5.3. Endogenous Solution

To overcome the problems of endogeneity and the self-selection of variables that may arise from regression estimation methods, this study used PSM to verify the effect of centralized Internet or television use for news on rural residents’ social trust. Referring to Rosenbaum and Rubin, this study adopted the PSM method, which is an approximate natural experiment method that can effectively overcome the error and endogeneity problems caused by sample selection bias [

74]. This study divided the population into two groups: rural residents who used the Internet or television and rural residents who did not use either. The intervention conditions were defined according to the dichotomous variables; the treated group included rural residents who used the Internet or television and the control group included rural residents who did not use either. Multiple covariates had to be controlled for in order to match the rural residents who used the Internet or television with the most similarly characterized rural residents who did not use the Internet or television, and the selected covariates included all the control variables after regression according to the Probit model in the previous section.

After the above operation, this study formally applied nearest-neighbor matching (non-substitution), radius matching (r = 0.05), and kernel matching for estimation. As shown in

Table 5, Internet and television use for news had a significant effect on rural residents’ social trust. The average treatment effect on the ATT values for the treated groups after propensity score matching reached about 5% and 3%, respectively, indicating that rural residents would be 5% or 3% more likely to trust others if they used the Internet for news. In contrast, the regression results of the Probit model showed some overestimation.

5.4. Substitution Effect of Information Access Modes

Rural residents usually have multiple information sources, and they use them in decision-making. If needed, they look for information via alternative modes to make decisions [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. This subsection validated the substitution effect of information access modes using the Stata 16.0 software based on 12,042 rural residents from the CPFS 2018 survey data. From columns (1) and (2) in

Table 6, it can be seen that, after the cross terms were added, the influence coefficients of the Internet and television were still significant and positive at the 1% level, and the influence coefficient of the cross terms was negative and significant at the 1% significance level, indicating that there may be a substitution effect between the two information access modes. In column (3), the influence coefficients of Internet and television, as well as the cross terms, remained significant after the control variables were added, indicating that a substitution effect existed, validating Hypothesis 3. This suggests that when the frequency of using television for news decreased or was limited, the frequency of using the Internet increased, and vice versa.

5.5. Analysis of Heterogeneous Effects

5.5.1. Heterogeneity Analysis of Residents with Different Characteristics

Since China’s reform and opening up, with the gradual deepening of the division of labor and industry and market economy reform, the internal differentiation of farmers’ groups is more detailed, and the needs and preferences of different groups may have different behavioral responses to social trust. According to previous research, on the one hand, due to the unbalanced economic development of each region in China, there are inevitable differences in information accessibility and network infrastructure construction between rural residents and urban residents and between people with different characteristics of rural residents. On the other hand, due to the different social environment and living habits, the factors influencing social trust of rural residents compared with urban residents may also have certain special characteristics [

30,

84,

85,

86]. When studying the influence of information access methods on social trust, if only a single sample of rural residents is analyzed, the sample differences between groups are inevitably ignored and it is difficult to obtain a reasonable understanding of the actual situation of social trust among rural residents [

31,

87]. For this reason, this subsection aimed to identify the characteristics of social trust among rural residents by conducting a comparative analysis of information access patterns and influencing social trust among rural residents and urban residents and among people with different characteristics of rural residents.

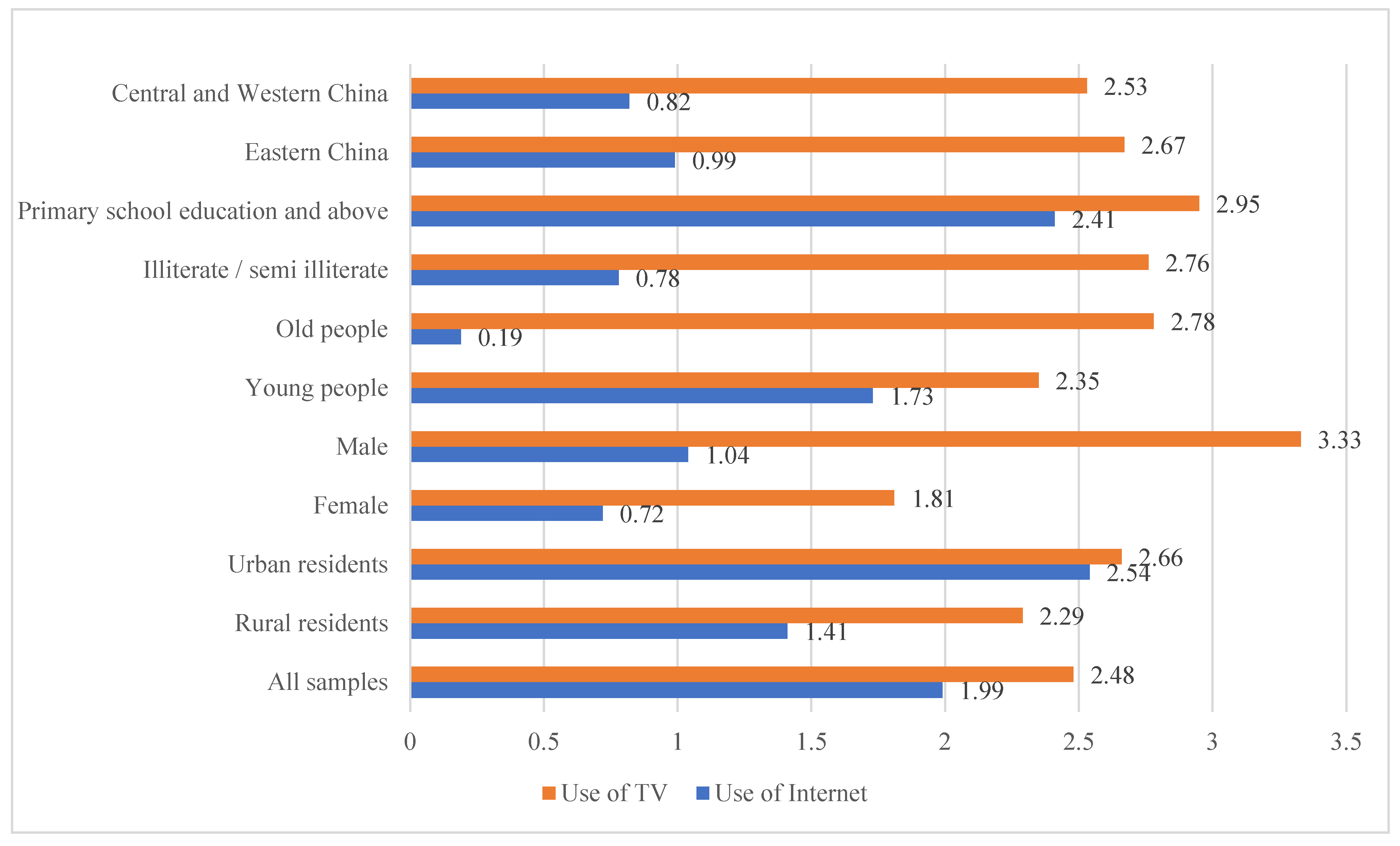

As seen in

Figure 4, urban residents used the Internet and television an average of 1.13 and 0.37 days more per week than rural residents, intuitively indicating that urban residents used television and the Internet more frequently than rural residents to obtain news and information. The 19.27% difference between the sample of urban and rural residents who did not use the Internet as extremely likely due to the poor communication and network facilities in rural areas, which are more difficult for rural residents to access; the value of 17.61% of the sample of rural residents who used the Internet frequently (more than 4 days per week) was lower than the value of 33.09% of the sample of urban residents. The label of information-disadvantaged can be clearly seen in the comparison of populations among rural residents, mainly women, illiterate/semi-literate, and elderly, who used the Internet and TV to access information significantly less frequently than men, highly educated, and young people. There was little difference in the frequency of Internet and TV use between rural residents in the eastern region and those in the central and western regions.

5.5.2. Differences in the Effects of Using the Internet and TV on the Social Trust for Different Groups of People

As seen in

Table 7, the regression results in column (1) show that there was a significant effect of using the Internet and television to access news on the social trust of urban residents, with coefficients of 0.014 and 0.015, respectively, which were significant at the 1% level, indicating that for each additional day of use by urban residents who used the Internet and television to access news and information, the trust of urban residents in others increased by a 1.4% and 1.5% probability. The higher coefficient of the Internet’s effect on rural residents suggested that the social trust of rural residents was more susceptible to the new media of the Internet relative to urban residents. Although there were differences in the time of Internet and TV usage between urban and rural areas, as well as the different economic and social situations in which they live, the mode of information access had the same significant positive effect on the social trust of rural and urban residents, which was consistent with Xu’s and Wang’s studies [

30,

88].

From columns (2) to (9) in

Table 7, the regression results are presented for the subsamples of females, males, young people, old people, illiterate/semi-literate, individuals with primary school education and above, eastern China, central China, and western China, respectively. It can be seen that Internet and TV were not significant factors for illiterate/semi-literate people in rural areas due to the “digital divide” phenomenon. This suggests that the difference in educational attainment may lead to a lack of access to the dividends of information technology among the rural population with low educational attainment. In addition, the coefficient of trust in others was higher for both male and female rural residents who used the Internet to access news and information one day a week, and the coefficient was higher for women than for men, but the coefficient of the effect of television use was not significant for women. A possible reason is that women in rural areas usually have to do housework, so they do not often use TV to obtain news information, so they will obtain the information through the Internet instead. The coefficients of Internet and TV use were higher for older than younger people, indicating that older people were more likely to be influenced by information and have increased trust in others relative to younger people. The coefficients of Internet and TV use were higher for rural residents in eastern China than for those in central and western China, indicating that rural residents in eastern China were more likely to be influenced by information and to increase their trust in others, which was consistent with Wang’s study [

13].

6. Discussion

In recent years, the Internet has gradually replaced traditional media in China as the main source of information for rural residents. This has shaped the social trust of rural residents to some extent, and it has been effectively verified in this study. Specifically, based on the Probit model, the PSM model and the large sample data from China, we found a positive correlation, heterogeneous effects of the Internet, TV, and rural residents, as well as a substitution relationship between the Internet and TV when they exerted effects on rural residents’ social trust.

Given this, to better guide the spread of public opinions on the Internet and improve rural residents’ social trust, the following policy recommendations are proposed based on the research conclusions of this study:

The positive influence of modern media such as the Internet and television on social trust should be highly valued to effectively enhance rural residents’ social trust. It is necessary to fully guide to the positive role of modern media in promoting rural governance capacity, as well as to pay greater attention to the amplification and negative impact of modern media. Governments should strengthen the standardized management of modern media, establish a sound mechanism to respond to and deal with public opinion events related to agriculture, increase the disposal of false, misinforming, and negative propaganda, and improve the public communication environment in rural areas so that more positive information can be shared in order to enhance rural residents’ social trust [

89]. Governments should improve the Internet and digital literacy of disadvantaged groups of rural residents and combat and eliminate the “digital divide.” Furthermore, governments should accelerate the construction of information technology in rural areas, especially the construction of network infrastructure, so that disadvantaged groups in rural areas can access the necessary information resources [

90,

91].

7. Conclusions

This study empirically investigated the influence of information access modes on rural residents’ social trust using various econometric models to understand the mechanism of the effect of modern media such as Internet and television use on rural residents’ social trust and to provide a reference for promoting digital rural governance and improving social trust in rural areas. This study’s findings are as follows:

From the regression, the two information access modes—Internet and television—did have a significant positive effect on rural residents’ social trust, and the influence coefficient of the Internet was higher than that of television. Specially, rural residents’ trust in others increased if they increased their weekly Internet and television use for news, owing to the “media propaganda and mobilization effect.”

According to the significant and negative coefficient of the cross terms in the regression results, there was a substitution effect between the information access modes, that is, when rural residents used the Internet and television for news, if they did not receive enough information via one mode or restricted mode, they sought additional information via the other mode.

The descriptive statistics showed that rural Chinese residents had the highest level of trust in parents, followed by trust in doctors, neighbors, and cadres, and the lowest trust in strangers. The information-disadvantaged groups among rural residents were mainly women, old people, and people with low education.