The Influence of Mall Management Dimensions on Perceived Experience and Patronage Intentions in an Emerging Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Literature Review

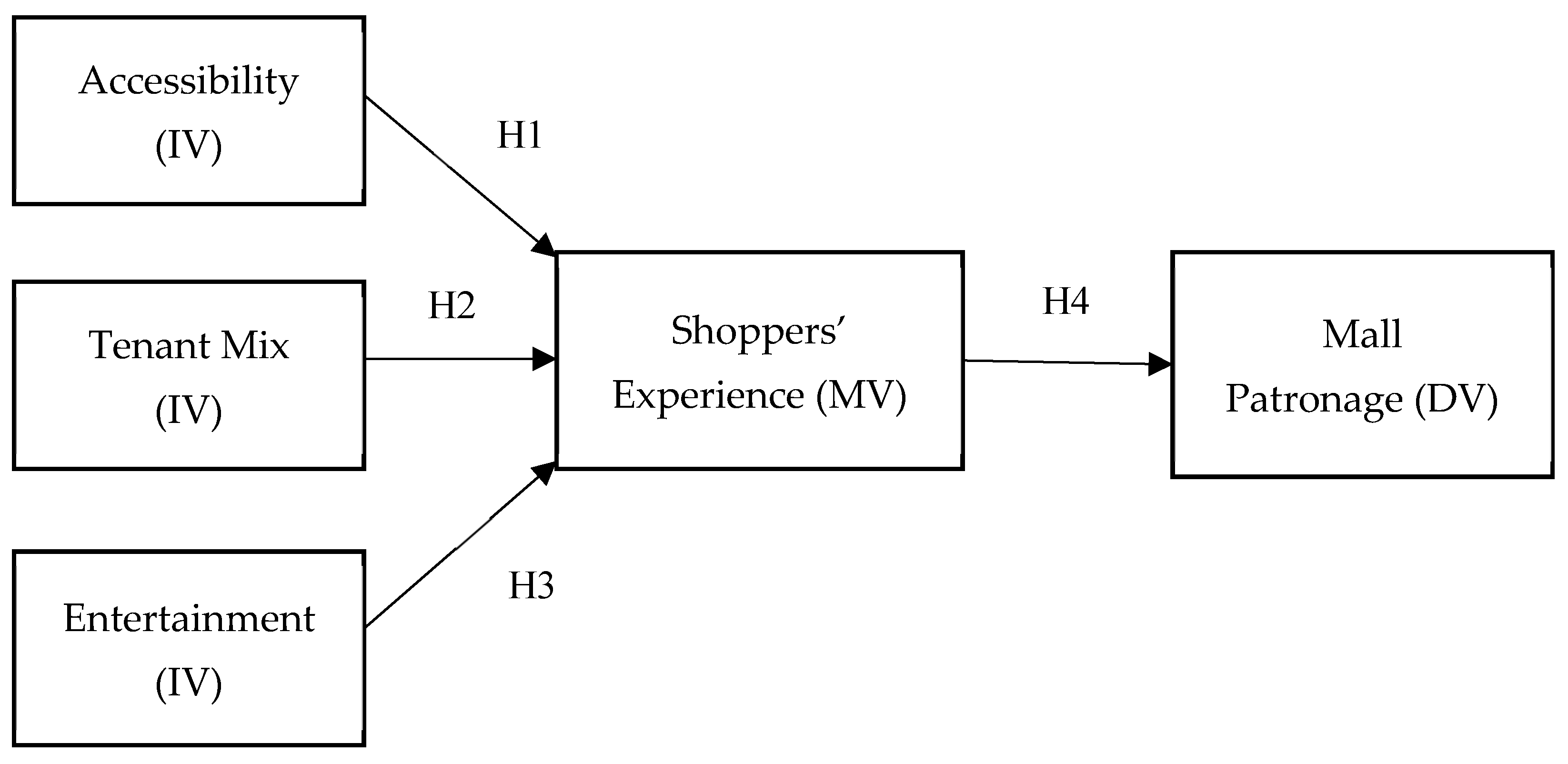

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Accessibility

2.2.2. Tenant Mix

2.2.3. Entertainment

2.2.4. Shoppers’ Experience

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Development of Research Instruments

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. Research Application Used

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Demographic Variables

4.2. Reliability and Discriminant Validity

4.2.1. Reliability

4.2.2. Discriminant Validity

4.3. Normality Testing

4.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.5. Structural Equation Modelling

5. Discussion and Implications for Managers

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Scope for Future Research

7.1. Limitations

7.2. Future Research Scope

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank National Accounts Data, and OECD National Accounts Data Files. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=BD (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Bangladesh Startup Ecosystem 2021–2022. Available online: https://www.lightcastlebd.com/insights/2022/07/bangladesh-startup-ecosystem-report-2021-22/ (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- South Asia Economic Focus, Fall 2019: Making (De)centralization Work. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/32515 (accessed on 29 April 2020).

- World Economic League Table 2020. Available online: https://cebr.com/reports/world-economic-league-table-2020/ (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Mujeri, M. Bangladesh’s Rising Middle Class: Myths and Realities. Available online: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/bangladeshs-rising-middle-class-myths-and-realities-1614610680 (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Singh, H.; Sahay, V. Determinants of shopping experience: Exploring the mall shoppers of national capital region (NCR) of India. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Prashar, S. Anatomy of shopping experience for malls in Mumbai: A confirmatory factor analysis approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Hernández, E.M.; Orozco-Gomez, M. A segmentation study of Mexican consumers based on shopping centre attractiveness. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 759–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbanee, F.K.; Ramaseshan, B.; Wu, C.; Vinden, A. Effects of store loyalty on shopping mall loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2012, 19, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullis, K.; Kim, M. Factors determining in shopping in rural US communities: Consumers’ and retailers’ perceptions. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2011, 39, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Stoel, L. Factors contributing to rural consumers’ in shopping behavior: Effects of institutional environment and social capital. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2010, 28, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seock, Y.K.; Lin, C. Cultural influence on loyalty tendency and evaluation of retail store attributes: An analysis of Taiwanese and American consumers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2011, 39, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, I.; Banga, S. The economic and social role of small stores: A review of UK evidence. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2010, 20, 187–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satish, K.; Venkatesh, A.; Manivannan, A.S.R. Covid-19 is driving fear and greed in consumer behaviour and purchase pattern. S. Asian J. Mark. 2021, 2, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Baker, J. Excitement at the mall: Determinants and effects on shopping response. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmsson, J. Sources of customer satisfaction with shopping malls: A comparative study of different customer segments. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2006, 16, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.P. Shopping mall management and entertainment experience: A cross-regional investigation. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.U.; Ghingold, M.; Dahari, Z. Malaysian shopping mall behavior: An exploratory study. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2007, 19, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underhill, P. Why We Buy: The Science of Shopping—Updated and Revised for the Internet, the Global Consumer, and Beyond; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ooi, J.T.; Sim, L.L. The magnetism of suburban shopping centers: Do size and Cineplex matter. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2007, 25, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Mohan, M.; Gupta, S.K. The effect of mall ambiance, layout, and utility on consumers’ escapism and repurchase intention. Innov. Mark. 2022, 18, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carù, A.; Cova, B. Revisiting consumption experience: A more humble but complete view of the concept. Mark. Theory 2003, 3, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Customer Experience Management; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Babin, B.J.; Attaway, J.S. Atmospheric affect as a tool for creating value and gaining share of customer. J. Bus. Res. 2000, 49, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coye, R.W. Managing customer expectations in the service encounter. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2004, 15, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Lemon, K.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Roggeveen, A.; Tsiros, M.; Schlesinger, L.A. Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckström, K. Understanding recreational shopping: A new approach. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2006, 16, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseki, M.I. Customer expectations in mall restaurants: A case study. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2013, 14, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Nsairi, Z.B. Managing browsing experience in retail stores through perceived value: Implications for retailers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 676–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, N. A study on the attractiveness dimensions of shopping malls- an Indian perspective. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, A.; Gupta, A.; Tripathi, V. Managing shopping experience through mall attractiveness dimensions: An experience of Indian metro cities. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2016, 28, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarijarvi, H.; Rintamaki, T.; Kuusela, H. Facilitating customers’ post-purchase retail experience. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 635–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavas, U. A multi-attribute approach to understanding shopper segments. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2003, 31, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodkin, C.D.; Lord, J.D. Attraction of power shopping centres. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 1997, 7, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F.J.M. Image of suburban shopping malls and two-stage versus uni-equational modelling of the retail trade attraction. Eur. J. Mark. 1999, 33, 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.A.F.; Li, F.; Kranendonk, C.J.; Roslow, S. The seven year itch? Mall shoppers across time. J. Consum. Mark. 2002, 19, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, A.; Louviere, J.J. Shopping center image, consideration, and choice: Anchor store contribution. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 35, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.F.; Ng, C.W. Determinants of entertaining shopping experiences and their link to consumer behaviour: Case studies of shopping centres in Singapore. J. Retail. Leis. Prop. 2002, 2, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa, S.; Vilnai-Yavetz, I. Shop until you drop? An exploratory analysis of mall experience. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.; Weitz, B.A.; Grewal, D. Retailing Management; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Frasquet, M.; Gil, I.; Molla, A. Shopping-centre selection modelling: A segmentation approach. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2001, 11, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, C.F. A new look at one-stop shopping: A TIMES model approach to matching store hours and shopper schedules. J. Consum. Mark. 1996, 13, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, M.M.K.; Qiu, R.C.Q. An empirical study of factors influencing consumers’ purchasing behaviours in shopping malls. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2021, 13, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arentze, T.A.; Oppewal, H.; Timmermans, H.J. A multipurpose shopping trip model to assess retail agglomeration effects. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowrey, C.H.; Beagle, J.K.; Gune, S.; Hirpara, S.; Parikh, P.J. Retail store layout: Shopper preference vs. shopper access. In Proceedings of the IISE Annual Conference and Expo 2021, Online, 22–25 May 2021; pp. 1034–1039. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85121014037&partnerID=40&md5=54fba6d1cce275484f7eba4695d21d38 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Kirkup, M.; Rafiq, M. Managing tenant mix in new shopping centres. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 1994, 22, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, P.Q. Shopping centre image dynamics of a new entrant. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2009, 37, 580–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Retail Marketing: A Branding and Innovation Approach; Tilde University Press: Prahran, VIC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yiu, C.Y.; Xu, S.Y. A tenant-mix model for shopping malls. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, G.; Marr, N.; Jarratt, B. An exploratory study of tenant-manager relationships in New Zealand’s managed shopping centres. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 1996, 24, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A.G.; Ballantine, P.W.; Roberts, J.; Merrilees, B.; Herington, C.; Miller, D. Building retail tenant trust: Neighbourhood versus regional shopping centres. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2010, 38, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terblanché, N.S. The perceived benefits derived from visits to a super-regional shopping centre: An exploratory study. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 1999, 30, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, P.H.; Ridgway, N.M.; Dawson, S.A. The shopping mall as consumer habitat. J. Retail. 1994, 70, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmashhara, M.G.; Soares, A.M. Entertain me, I’ll stay longer! The influence of types of entertainment on mall shoppers’ emotions and behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csaba, F.F.; Askegaard, S. Malls and the orchestration of the shopping experience in a historical perspective. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1999, 26, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Hirschman, E.C. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerin, R.A.; Jain, A.; Howard, D.J. Store shopping experience and consumer price-quality-value perceptions. J. Retail. 1992, 68, 376. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R.; Bagdare, S. Music and consumption experience: A review. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2011, 39, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Pine, J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, A. Customer experience management: A critical review of an emerging idea. J. Serv. Mark. 2010, 24, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.R.; Srivastava, R.K. Creating the futuristic retail experience through experiential marketing: Is it possible? An exploratory study. J. Retail. Leis. Prop. 2010, 9, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullman, M.E.; Gross, M.A. Ability of experience design elements to elicit emotions and loyalty behaviors. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 551–578. [Google Scholar]

- Anuradha, D.; Manohar, H.L. Customer shopping experience in malls with entertainment centres in Chennai. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 12319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail El-Adly, M. Shopping malls attractiveness: A segmentation approach. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 936–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf Ahmad, A. Attractiveness Factors Influencing Shoppers’ Satisfaction, Loyalty, and Word of Mouth: An Empirical Investigation of Saudi Arabia Shopping Malls. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2012, 3, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Jhamb, D. Determinants of shopping mall attractiveness: The Indian context. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, M.; Tandon, K. Mall Management: An analysis of customer footfall patterns in Shopping Malls in India. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2015, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.; Islam, M.; Sobhani, F.A. Patients’ Intention to Adopt Fintech Services: A Study on Bangladesh Healthcare Sector. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The partial least squares (PLS) approach to casual modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoe, S.L. Issues and procedures in adopting structural equation modeling technique. J. Appl. Quant. Methods 2008, 3, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ab Hamid, M.R.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M.M. Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R.P.; Ho, M.H.R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education International: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banytė, J.; Rūtelionė, A.; Jarusevičiūtė, A. Modelling of male shoppers behavior in shopping orientation context. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Atmospherics as a marketing tool. J. Retail. 1973, 49, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, J.; Talpade, S. Does entertainment draw shoppers? The effects of entertainment centers on shopping behavior in malls. J. Shopp. Cent. Res. 1996, 3, 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J.N. An integrative theory of patronage preference and behavior. In Patronage Behavior and Retail Management; Darden, W.R., Lusch, R.F., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 174 | 61.27 |

| Female | 110 | 38.73 |

| Total | 284 | 100.00 |

| Age | ||

| 16–20 | 35 | 12.32 |

| 21–30 | 183 | 64.44 |

| 31–40 | 45 | 15.85 |

| 41–50 | 16 | 5.63 |

| Above 50 | 5 | 1.76 |

| Total | 284 | 100.00 |

| Academic Qualification | ||

| Secondary School Certificate (SSC) | 2 | 0.70 |

| Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) | 71 | 25.00 |

| Graduate | 124 | 43.66 |

| Post Graduate | 80 | 28.17 |

| Others | 7 | 2.47 |

| Total | 284 | 100.00 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 159 | 55.99 |

| Homemaker | 16 | 5.63 |

| Businessperson/Self-employed | 9 | 3.17 |

| Private Service | 89 | 31.34 |

| Govt. Service | 5 | 1.76 |

| Others | 6 | 2.11 |

| Total | 284 | 100.00 |

| Monthly Family Income (BDT) | ||

| Less than 25,000 | 37 | 13.03 |

| 25,001–50,000 | 90 | 31.69 |

| 50,001–75,000 | 70 | 24.65 |

| 75,001–100,000 | 44 | 15.49 |

| Above 100,000 | 43 | 15.14 |

| Total | 284 | 100.00 |

| Frequency of Shopping Mall Visit | ||

| Once a month | 149 | 52.47 |

| Once every two weeks | 43 | 15.14 |

| Once a week | 92 | 32.39 |

| Total | 284 | 100.00 |

| Time Spent on Each Visit (in hours) | ||

| Less than 1 | 33 | 11.62 |

| 1–2 | 154 | 54.23 |

| More than 2 | 97 | 34.15 |

| Total | 284 | 100.00 |

| Primary Reason for Visiting | ||

| Entertainment | 22 | 7.75 |

| Shopping | 182 | 64.08 |

| Have a good time out with friends/families | 55 | 19.37 |

| Explore new product | 25 | 8.80 |

| Total | 284 | 100.00 |

| Constructs | Accessibility | Tenant Mix | Entertainment | Shoppers’ Experience | Patronage | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.776 | 0.798 | 0.825 | 0.835 | 0.794 | 0.912 |

| No. of Items | 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 24 |

| Goodness-of-Fit Statistics | Normed Chi-Square | RMSEA | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility (ACC) | 1.528 | 0.043 | 0.956 |

| Tenant mix (TEN) | 1.253 | 0.030 | 0.992 |

| Entertainment (ENT) | 1.104 | 0.019 | 0.999 |

| Shoppers’ experience (EXP) | 2.277 | 0.067 | 0.977 |

| Patronage (PAT) | 1.479 | 0.041 | 0.997 |

| Threshold values for the fit indices | <5.0 | <0.08 | >0.90 |

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC → EXP | 0.605 | 0.105 | 5.758 | 0.001 | Supported |

| TEN → EXP | 0.069 | 0.064 | 1.090 | 0.276 | Not Supported |

| ENT → EXP | 0.416 | 0.053 | 7.870 | 0.001 | Supported |

| EXP → PAT | 0.773 | 0.083 | 9.359 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Hypothesis Statement | Result |

|---|---|

| H1. Accessibility exerts a positive impact on shoppers’ experience. | Accepted |

| H2. Tenant mix is positively related to shoppers’ experience. | Rejected |

| H3. Entertainment has a positive impact on shoppers’ experience. | Accepted |

| H4. Shoppers’ experience has a positive impact on mall patronage. | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahmud, I.; Ahmed, S.; Sobhani, F.A.; Islam, M.A.; Sahel, S. The Influence of Mall Management Dimensions on Perceived Experience and Patronage Intentions in an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043258

Mahmud I, Ahmed S, Sobhani FA, Islam MA, Sahel S. The Influence of Mall Management Dimensions on Perceived Experience and Patronage Intentions in an Emerging Economy. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043258

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahmud, Imroz, Shamsad Ahmed, Farid Ahammad Sobhani, Md Aminul Islam, and Samira Sahel. 2023. "The Influence of Mall Management Dimensions on Perceived Experience and Patronage Intentions in an Emerging Economy" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043258

APA StyleMahmud, I., Ahmed, S., Sobhani, F. A., Islam, M. A., & Sahel, S. (2023). The Influence of Mall Management Dimensions on Perceived Experience and Patronage Intentions in an Emerging Economy. Sustainability, 15(4), 3258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043258