The Price of Organic Foods as a Limiting Factor of the European Green Deal: The Case of Tomatoes in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Consumer Preferences for Organic Food

3.2. Consumers’ Environmental Values and Lifestyles

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Comission. The European Green Deal; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; WHO. Codex Alimentarius Commission. In Twenty-Third Session; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1999; p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Klintman, M.; Boström, M. Political consumerism and the transition towards a more sustainable food regime: Looking behind and beyond the organic shelf. In Food Practices in Transition: Changing Food Consumption, Retail and Production in the Age of Reflexive Modernity; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterveer, P.; Spaargaren, G. Green consumption practices and emerging sustainable food regimes: The role of consumers. In Food Practices in Transition; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Vittersø, G.; Tangeland, T. The role of consumers in transitions towards sustainable food consumption. The case of organic food in Norway. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 92, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacko, M.; Reisch, L.; Scholl, G. Sustainable food consumption: When evidence-based policy making meets policy-minded research–Introduction to the special issue. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Consumers’ purchasing decisions regarding environmentally friendly products: An empirical analysis of German consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, G.; Choudhary, S.; Kumar, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Khan, S.A.R.; Panda, T.K. Do altruistic and egoistic values influence consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions towards eco-friendly packaged products? An empirical investigation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, C.; Gattinger, A.; Krauss, M.; Krause, H.-M.; Mayer, J.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Mäder, P. The impact of long-term organic farming on soil-derived greenhouse gas emissions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisander, J. Motivational complexity of green consumerism. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Chang, Z.; Tran, M.C.; Cohen, D.A. Consumer Attitudes toward the Purchase of Organic Products in China. Int. J. Bus. Econ. 2016, 15, 117–144. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Verma, P. Factors influencing Indian consumers’ actual buying behaviour towards organic food products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Zamora, M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J.; Murgado-Armenteros, E.M.; Parras-Rosa, M. Organic as a Heuristic Cue: What Spanish Consumers Mean by Organic Foods. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żakowska-Biemans, S. Polish consumer food choices and beliefs about organic food. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.; Wong, F.; Jones, C.; Russell, J. Food Purchasing Decisions and Environmental Ideology: An Exploratory Survey of UK Shoppers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.M.; Phan, T.H.; Nguyen, H.L.; Dang, T.K.T.; Nguyen, N.D. Antecedents of Purchase Intention toward Organic Food in an Asian Emerging Market: A Study of Urban Vietnamese Consumers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Zamora, M.; Parras-Rosa, M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J. You Are What You Eat: The Relationship between Values and Organic Food Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.J.; Norton, L.R.; Feber, R.E.; Johnson, P.J.; Chamberlain, D.E.; Joys, A.C.; Mathews, F.; Stuart, R.C.; Townsend, M.C.; Manley, W.J.; et al. Benefits of organic farming to biodiversity vary among taxa. Biol. Lett. 2005, 1, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeder, P.; Fliessbach, A.; Dubois, D.; Gunst, L.; Fried, P.; Niggli, U. Soil Fertility and Biodiversity in Organic Farming. Science 2002, 296, 1694–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Zamora, M.; Parras-Rosa, M.; Murgado-Armenteros, E.M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J. A powerful word: The influence of the term’organic’on perceptions and beliefs concerning food. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lockie, S.; Lyons, K.; Lawrence, G.; Mummery, K. Eating ‘Green’: Motivations behind organic food consumption in Australia. Sociol. Rural. 2002, 42, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifferstein, H.N.J.; Oude Ophuis, P.A.M. Health-related determinants of organic food consumption in The Netherlands. Food Qual. Prefer. 1998, 9, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, L.; Juric, B.; Bettina Cornwell, T. Level of market development and intensity of organic food consumption: Cross-cultural study of Danish and New Zealand consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torjusen, H.; Lieblein, G.; Wandel, M.; Francis, C.A. Food system orientation and quality perception among consumers and producers of organic food in Hedmark County, Norway. Food Qual. Prefer. 2001, 12, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoli, R.; Naspetti, S. Consumer motivations in the purchase of organic food. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, M.K.; Arvola, A.; Hursti, U.-K.K.; Åberg, L.; Sjödén, P.-O. Choice of organic foods is related to perceived consequences for human health and to environmentally friendly behaviour. Appetite 2003, 40, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chryssohoidis, G.M.; Krystallis, A. Organic consumers’ personal values research: Testing and validating the list of values (LOV) scale and implementing a value-based segmentation task. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padel, S.; Foster, C. Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiridoe, E.K.; Bonti-Ankomah, S.; Martin, R.C. Comparison of consumer perceptions and preference toward organic versus conventionally produced foods: A review and update of the literature. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2005, 20, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Vecchio, R. Organic Farming and Sustainability in Food Choices: An Analysis of Consumer Preference in Southern Italy. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitner-Schobesberger, B.; Darnhofer, I.; Somsook, S.; Vogl, C.R. Consumer perceptions of organic foods in Bangkok, Thailand. Food Policy 2008, 33, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoli, R. How country-specific are consumer attitudes towards organic food. In Proceedings of the Annual IBL Meeting:“Looking for a Market! Which Knowledge Is Needed for Further Development of the Market on Organic Farming?”, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 15 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dangi, N.; Gupta, S.K.; Narula, S.A. Consumer buying behaviour and purchase intention of organic food: A conceptual framework. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2020, 31, 1515–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, P.; Furková, A.; Reiff, M.; Konštiak, P.; Sitášová, J. Impact of Consumer Preferences on Food Chain Choice: An empirical study of consumers in Bratislava. Acta Univ. Agric. Et Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2017, 65, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosona, T.; Gebresenbet, G. Swedish Consumers’ Perception of Food Quality and Sustainability in Relation to Organic Food Production. Foods 2018, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J.C.; Duke, J.M.; Albrecht, S.E. Do labels that convey minimal, redundant, or no information affect consumer perceptions and willingness to pay? Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska, D.; Radzymińska, M. Health and environmental attitudes and values in food choices: A comparative study for Poland and Czech Republic. Oeconomia Copernic. 2019, 10, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profeta, A.; Hamm, U. Do consumers prefer local animal products produced with local feed? Results from a Discrete-Choice experiment. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderjahn, I. Personality variables and environmental attitudes as predictors of ecologically responsible consumption patterns. J. Bus. Res. 1988, 17, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.; Murphy, L. Who’s buying organic food and why? Political consumerism, demographic characteristics and motivations of consumers in North Queensland. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2013, 9, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Katzeff, C.; Milestad, R.; Zapico, J.L.; Bohné, U. Encouraging organic food consumption through visualization of personal shopping data. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddock, J. Invoking Simplicity: ‘Alternative’ Food and the Reinvention of Distinction. Sociol. Rural. 2015, 55, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sánchez, V.-M.; Pérez-Flores, A.-M. The Connections between Ecological Values and Organic Food: Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review at the Start of the 21st Century. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Demografía y Población; INE: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Green, P.E.; Rao, V.R. Conjoint measurement from quantifying judgemental data. J. Mark. Res. 1971, 8, 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A.; Huppes, G.; Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Koning, A.; Oers, L.; Suh, S.; Geerken, T.; Van Holderbeke, M.; Jansen, B.; et al. Environmental Impact of Products (EIPRO) Analysis of the life cycle environmental impacts related to the final consumption of the EU-25. In Technical Report Series; Publications Office of the European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 1–136, EUR 22284 EN. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0; Guide user; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, R.E. Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Steekamp, J.B. Conjoint measurement in ham quality evaluation. J. Agric. Econ. 1987, 38, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Análisis Multivariante; Prentice-Hall: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Halbrendt, C.K.; Wirth, F.F.; Vaughn, G.F. Conjoint Analysis of the Mid-Atlantic Food-Fish Market for Farm-Raised Hybrid Striped Bass. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 1991, 23, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Luzar, E.J. A Conjoint Analysis of Waterfowl Hunting in Louisiana. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 1993, 25, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretton-Clark. Conjoint Designer and Conjoint Analyzer, Version 2.0; Bretton-Clark: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Dispoto, R.G. Interrelationships Among Measures of Environmental Activity, Emotionality, and Knowledge. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 37, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, S.C.; Røhme, N. Consumer’s environmental concern: Are we really tapping true concern that relates to environmentally ethic behavior? In Proceedings of ESOMAR Conference on Marketing and Research under a New World Order, Tokyo, Japan, 6–8 July 1992.

- Park, C.W.; Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Feick, L. Consumer Knowledge Assessment. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K. Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schahn, J.; Holzer, E. Studies of Individual Environmental Concern:The Role of Knowledge, Gender, and Background Variables. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, H. The Evolving Organic Marketplace; Hartman New Hope: Bellevue, WA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzaoui-Essoussi, L.; Zahaf, M. Canadian Organic Food Consumers’ Profile and Their Willingness to Pay Premium Prices. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2012, 24, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grymshi, D.; Crespo-Cebada, E.; Elghannam, A.; Mesías, F.J.; Díaz-Caro, C. Understanding consumer attitudes towards ecolabeled food products: A latent class analysis regarding their purchasing motivations. Agribusiness 2022, 38, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustad, T.P.; Pessemier, E.A. The Development and Application of Psychographic Life Style and Associated Activity and Attitude Measures; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1974; pp. 31–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mowen, J.C. Consumer Behavior; Macmillan Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 413–423. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzell, R.D. Can You Standardize Multinational Marketing? Reprint Service, Harvard Business Review: Brighton, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.C. Standardization of International Marketing Strategy: Some Research Hypotheses. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, M.; Sharp, J. Profiling alternative food system supporters: The personal and social basis of local and organic food support. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2011, 26, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.M.; Gracia, A.; Sánchez, M. Market segmentation and willingness to pay for organic products in Spain. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2000, 3, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, T.B.; Andersen, L.M.; O’Doherty Jensen, K. The Emergence of Diverse Organic Consumers: Does a Mature Market Undermine the Search for Alternative Products? Sociol. Rural. 2013, 53, 454–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ureña, F.; Bernabéu, R.; Olmeda, M. Women, men and organic food: Differences in their attitudes and willingness to pay. A Spanish case study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerding, S.G.H.; Trajer, N.; Lehberger, M. What is local food? The case of consumer preferences for local food labeling of tomatoes in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbola, Y.P.; Ahoyo Adjovi, N.R.; Adekambi, S.A.; Zossou, R.; Sonehekpon, E.S.; Assogba Komlan, F.; Djossa, E. Consumer Preferences for Fresh Tomatoes in Benin using a Conjoint Analysis. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürkenbeck, K.; Spiller, A.; Meyerding, S.G.H. Tomato attributes and consumer preferences—A consumer segmentation approach. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Caselles, C.; Brugarolas, M.; Martínez-Carrasco, L. Traditional Varieties for Local Markets: A Sustainable Proposal for Agricultural SMEs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadinu, C.M.; Rodriguez, M.; Madau, F.; Attene, G. The value of agrobiodiversity: An analysis of consumers preference for tomatoes. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2022, 37, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourmouzi, V.; Genius, M.; Midmore, P. The Demand for Organic and Conventional Produce in London, UK: A System Approach. J. Agric. Econ. 2012, 63, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Huang, C.L.; Lin, B.-H.; Epperson, J.E.; Houston, J.E. National Demand for Fresh Organic and Conventional Vegetables: Scanner Data Evidence. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2011, 17, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, E.; Lopez, R.A. Demand for differentiated milk products: Implications for price competition. Agribusiness 2009, 25, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Otter, T.; Allenby, G.M. Measurement of own- and cross-price effects. In Handbook of Pricing Research in Marketing; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Röös, E.; Tjärnemo, H. Challenges of carbon labelling of food products: A consumer research perspective. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 982–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. Sustainability in the food sector: A consumer behaviour perspective. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2011, 2, 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wallnoefer, L.M.; Riefler, P.; Meixner, O. What Drives the Choice of Local Seasonal Food? Analysis of the Importance of Different Key Motives. Foods 2021, 10, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugarolas, M.; Martinez-Carrasco, L.; Bernabeu, R.; Martinez-Poveda, A. A contingent valuation analysis to determine profitability of establishing local organic wine markets in Spain. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2010, 25, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Rovira, A. Comportamiento del Consumidor: Comprendiendo al Consumidor; Prentice-Hall: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fraj, E.; Martínez, E. Comportamiento del Consumidor Ecológico; ESIC: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- De Magistris, T.; Gracia, A. The decision to buy organic food products in Southern Italy. Br. Food J. 2008, 110, 929–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.; Bernabéu, R. Consumer attitudes to organic foods. A Spanish case study. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2012, 30, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, S. Responsibility and agency within alternative food networks: Assembling the “citizen consumer”. Agric. Hum. Values 2009, 26, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, M.; Prieto, A.; Bernabeú, R. Estructura de preferencias de los consumidores de carne de cordero en Castilla-La Mancha. ITEA 2013, 109, 476–491. [Google Scholar]

- Alvensleben, R.V.; Altmann, M. Determinants of The Demand for Organic Food in Germany (F.R.). Acta Hortic. 1987, 203, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, J.; Soler, F.; Díez, I.; Sánchez, M.; Sanjuán, A.; Ben Kaakia, M.; Gracia, A. Potencial de mercado de los productos ecológicos en Aragón; Diputación General de Aragó: Zaragoza, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Clarke-Hill, C.; Shears, P.; Hillier, D. Retailing organic foods. Br. Food J. 2001, 103, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, M.S.; Aldamiz-Echevarría, C.; Charterina, J.; Vicente, A. El consumidor ecológico. Un modelo de comportamiento a partir de la recopilación y análisis de la evidencia empírica. Distrib. Y Consumo 2003, 67, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, S. Why organic food in Germany is a merit good. Food Policy 2003, 28, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, A.; Messina, F. Attitudes towards organic foods and risk/benefit perception associated with pesticides. Food Qual. Prefer. 2003, 14, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozan, A.; Stenger, A.; Willinger, M. Willingness-to-pay for food safety: An experimental investigation of quality certification on bidding behaviour. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2004, 31, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). World Agriculture: Towards 2015/2030; An FAO perspective; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lockie, S.; Halpin, D. The ‘Conventionalisation’ Thesis Reconsidered: Structural and Ideological Transformation of Australian Organic Agriculture. Sociol. Rural. 2005, 45, 284–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banterle, A.; Ricci, E.C. Does the Sustainability of Food Products Influence Consumer Choices? The Case of Italy. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2013, 4, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, A.; Ricci, E.C.; Solesin, M.; Banterle, A. Can Health and Environmental Concerns Meet in Food Choices? Sustainability 2014, 6, 9494–9509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Europea (CE). Reglamento (CE) No 834/2007 del Consejo de 28 de junio de 2007 sobre producción y etiquetado de los productos ecológicos. In Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea de 20 Julio de 2007; Unión Europea: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve, M.; Roca, J. Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud: Un nuevo parámetro a tener en cuenta. Med. Clín. 1997, 108, 458–459. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission. Key Policy Objectives of the Future CAP; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowska, D.; Radzymińska, M. Attitudes and behaviour of Warmia and Mazury residents towards issues related to environmental protection. In Zeszyty Naukowe Akademii Morskiej w Gdyni; Gdynia Maritime University: Gdynia, Poland, 2015; Volume 88. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarini, G.A.; Zimmermann, J.; Visschers, V.H.M.; Siegrist, M. Does environmental friendliness equal healthiness? Swiss consumers’ perception of protein products. Appetite 2016, 105, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockie, S.; Lyons, K.; Lawrence, G.; Grice, J. Choosing organics: A path analysis of factors underlying the selection of organic food among Australian consumers. Appetite 2004, 43, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.A.; Murray, D.L. Ethical Consumption, Values Convergence/Divergence and Community Development. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2013, 26, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.; Lang, T. Sustainable diets: How ecological nutrition can transform consumption and the food system; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Sánchez, V.M.; Pérez Flores, A.M. Acercamiento a las implicaciones existentes entre alimentación, calidad de vida y hábitos de vida saludables en la actualidad. Rev. De Humanid. 2015, 25, 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Onozaka, Y.; Nurse, G.; Thilmany, D.D. Local food consumers: How motivations and perceptions translate to buying behavior. Choices 2010, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Reisch, L.; Eberle, U.; Lorek, S. Sustainable food consumption: An overview of contemporary issues and policies. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Card Number | Price (€/kg) a | Type | Origin | System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | Ribbed | Imported | Organic |

| 2 | 6 | Cherry | Regional | Conventional |

| 3 | 4 | Smooth | Imported | Conventional |

| 4 | 4 | Cherry | National | Organic |

| 5 | 4 | Ribbed | Regional | Organic |

| 6 | 2 | Cherry | Imported | Organic |

| 7 | 2 | Smooth | Regional | Organic |

| 8 | 6 | Smooth | National | Organic |

| 9 | 2 | Ribbed | National | Conventional |

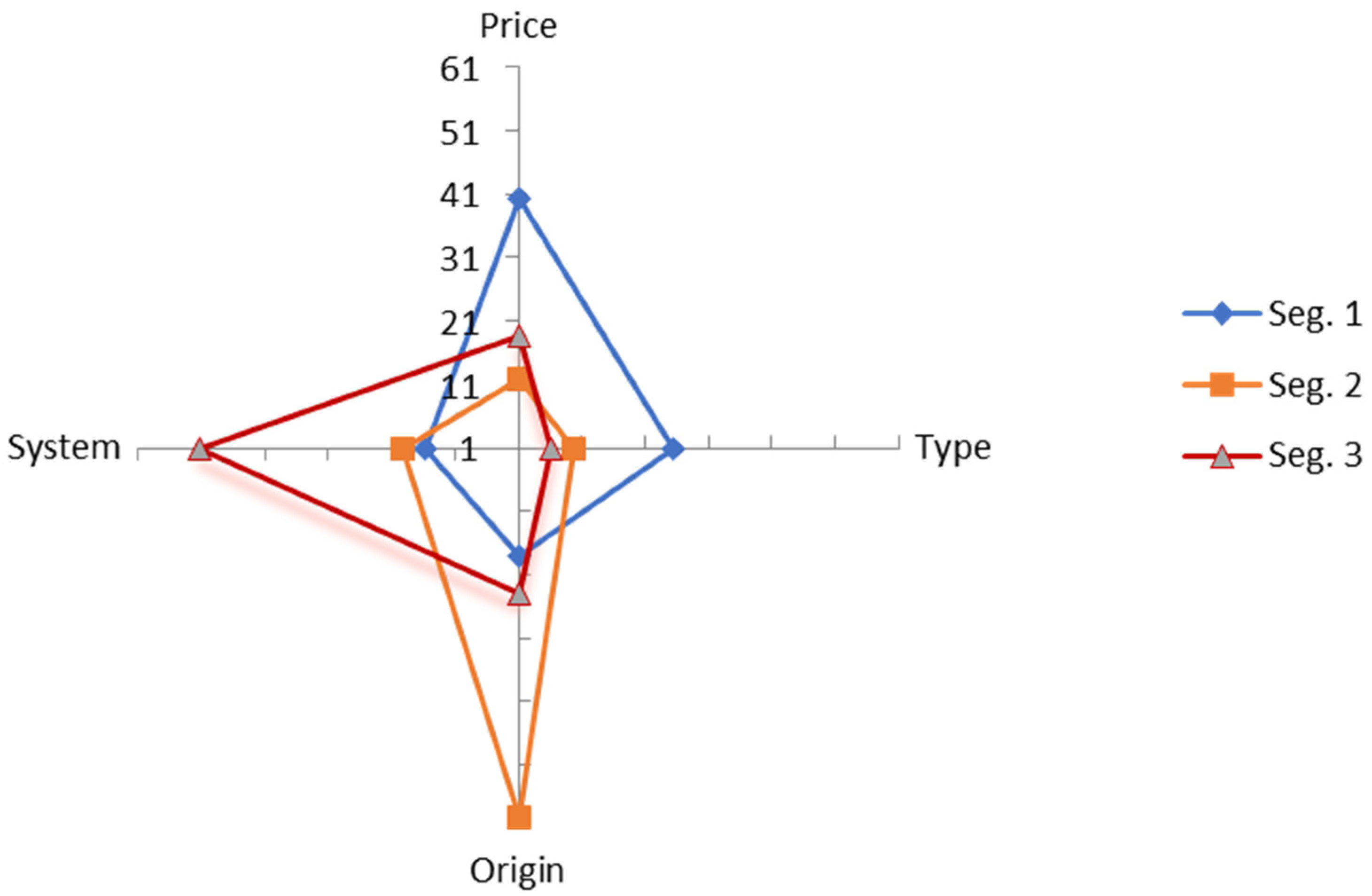

| Attributes and Levels | Segment 1 Price (49.6%) 1 | Segment 2 Origin (25.2%) 1 | Segment 3 System (25.2%) 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI (%) | Utilities | RI (%) | Utilities | RI (%) | Utilities | |

| Price (€/kg) *** | 40.6 | 11.8 | 18.7 | |||

| 2 *** | 0.636 | 0.317 | 0.422 | |||

| 4 *** | 0.032 | −0.052 | −0.109 | |||

| 6 *** | −0.668 | −0.265 | −0.303 | |||

| Type *** | 25.5 | 9.6 | 6.3 | |||

| Smooth *** | −0.063 | 0.139 | −0.018 | |||

| Ribbed *** | 0.441 | 0.168 | 0.134 | |||

| Cherry *** | −0.378 | −0.307 | −0.116 | |||

| Origin *** | 18.1 | 59.3 | 23.9 | |||

| Regional *** | 0.140 | 1.113 | 0.545 | |||

| National *** | 0.221 | 0.696 | −0.148 | |||

| Imported *** | −0.361 | −1.809 | −0.397 | |||

| System *** | 15.8 | 19.3 | 51.1 | |||

| Organic *** | 0.253 | 0.476 | 1.004 | |||

| Conventional *** | −0.253 | −0.476 | −1.004 | |||

| Constant | 4.803 | 4.838 | 5.150 | |||

| Price slope | −0.652 | −0.291 | −0.367 | |||

| MWTP 2 (€/kg) *** | 0.39 | 1.64 | 2.74 | |||

| Landscape/Product | Segment 1 Price MS (%) | Segment 2 Origin MS (%) | Segment 3 System MS (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System | Origin | Type | Price | ||||

| I | Organic | Regional | Smooth | 2.00 € | 11.9 | 25.2 | 30.8 |

| Conventional | Regional | Smooth | 2.00 € | 4.6 | 1.9 | 1.9 | |

| Organic | Regional | Ribbed | 2.00 € | 22.4 | 23.9 | 31.8 | |

| Conventional | Regional | Ribbed | 2.00 € | 7.8 | 10.2 | 7.3 | |

| Organic | National | Smooth | 2.00 € | 18.5 | 15 | 12.9 | |

| Conventional | National | Smooth | 2.00 € | 9 | 4.4 | 1.9 | |

| Organic | National | Ribbed | 2.00 € | 16.9 | 10.7 | 8.1 | |

| Conventional | National | Ribbed | 2.00 € | 8.9 | 8.7 | 5.3 | |

| II | Organic | Regional | Smooth | 4.00 € | 6.3 | 18.2 | 28.9 |

| Conventional | Regional | Smooth | 2.00 € | 10.3 | 9 | 3.9 | |

| Organic | Regional | Ribbed | 4.00 € | 15.9 | 23.8 | 31.6 | |

| Conventional | Regional | Ribbed | 2.00 € | 14.2 | 10.1 | 7.5 | |

| Organic | National | Smooth | 4.00 € | 12 | 9.7 | 11.8 | |

| Conventional | National | Smooth | 2.00 € | 15.5 | 9.7 | 2.9 | |

| Organic | National | Ribbed | 4.00 € | 10.8 | 8.3 | 6.8 | |

| Conventional | National | Ribbed | 2.00 € | 15 | 11.2 | 6.6 | |

| Indicators | Segment 1 Price (49.6%) | Segment 2 Origin (25.2%) | Segment 3 System (25.2%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | SD | Average | SD | Average | SD | |

| Current civilization is destroying nature *** | 4.21 a | ±1.09 | 4.29 a | ±1.07 | 4.56 b | ±0.75 |

| Unless measures are taken, environmental deterioration will become irreversible ** | 4.09 a | ±1.12 | 4.43 b | ±0.93 | 4.48 b | ±1.00 |

| I think agricultural activity is a major environmental contaminant *** | 2.92 a | ±1.24 | 3.05 a | ±1.30 | 3.41 b | ±1.19 |

| Ecology is a way for businesses to make sales | 3.30 | ±1.28 | 3.54 | ±1.09 | 3.41 | ±1.16 |

| I help in environmental conservation activities *** | 2.74 a | ±1.25 | 3.18 b | ±1.41 | 3.27 b | ±1.15 |

| I am concerned about the effects of human activity on climatic change and act accordingly ** | 3.61 a | ±1.14 | 3.75 a | ±1.16 | 3.99 b | ±1.12 |

| Indicators | Segment 1 Price (49.6%) | Segment 2 Origin (25.2%) | Segment 3 System (25.2%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | SD | Average | SD | Average | SD | |

| I control salt intake *** | 3.46 b | ±1.36 | 3.66 a | ±1.38 | 3.91 a | ±1.25 |

| I eat a vegetarian diet *** | 1.67 b | ±1.01 | 2.21 a | ±1.41 | 2.09 a | ±1.40 |

| I exercise regularly | 3.42 | ±1.30 | 3.76 | ±1.23 | 3.41 | ±1.22 |

| I try not to eat industrially produced food | 3.16 | ±1.29 | 3.65 | ±1.26 | 3.38 | ±1.13 |

| I often eat fruit and vegetables | 3.97 | ±1.16 | 4.30 | ±1.02 | 4.14 | ±1.18 |

| I eat red meat in moderation | 3.52 | ±1.25 | 3.71 | ±1.12 | 3.64 | ±1.26 |

| I belong to a nature defence association | 1.70 | ±1.14 | 1.90 | ±1.37 | 1.94 | ±1.30 |

| I try to eat food without artificial additives | 2.99 | ±1.22 | 3.46 | ±1.28 | 3.19 | ±1.42 |

| I voluntarily get periodic health check-ups *** | 3.05 b | ±1.40 | 3.61 a | ±1.27 | 3.51 a | ±1.31 |

| I try to reduce stress | 3.34 | ±1.34 | 3.52 | ±1.24 | 3.35 | ±1.24 |

| I contribute to non-profit organizations ** | 2.46 b | ±1.54 | 3.29 a | ±1.62 | 2.76 b | ±1.59 |

| I try to lead a methodical, orderly life | 3.66 | ±1.12 | 3.80 | ±1.15 | 3.60 | ±1.13 |

| I try to balance work and private time | 3.80 | ±1.14 | 3.84 | ±1.16 | 3.67 | ±1.17 |

| I read product labels *** | 3.54 b | ±1.34 | 4.08 a | ±1.13 | 3.90 a | ±1.13 |

| I prefer to use recycled products ** | 3.55 b | ±1.21 | 3.53 b | ±1.30 | 3.86 a | ±1.08 |

| I separate rubbish selective containers (organic, non-organic, batteries) | 4.11 | ±1.26 | 4.24 | ±1.33 | 4.06 | ±1.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernabéu, R.; Brugarolas, M.; Martínez-Carrasco, L.; Nieto-Villegas, R.; Rabadán, A. The Price of Organic Foods as a Limiting Factor of the European Green Deal: The Case of Tomatoes in Spain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043238

Bernabéu R, Brugarolas M, Martínez-Carrasco L, Nieto-Villegas R, Rabadán A. The Price of Organic Foods as a Limiting Factor of the European Green Deal: The Case of Tomatoes in Spain. Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043238

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernabéu, Rodolfo, Margarita Brugarolas, Laura Martínez-Carrasco, Roberto Nieto-Villegas, and Adrián Rabadán. 2023. "The Price of Organic Foods as a Limiting Factor of the European Green Deal: The Case of Tomatoes in Spain" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043238

APA StyleBernabéu, R., Brugarolas, M., Martínez-Carrasco, L., Nieto-Villegas, R., & Rabadán, A. (2023). The Price of Organic Foods as a Limiting Factor of the European Green Deal: The Case of Tomatoes in Spain. Sustainability, 15(4), 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043238