Abstract

The cutting-edge development known as FinTech is now fast replacing traditional financial services all over the world. Despite that, UAE consumers are still not embracing FinTech services at the expected rate. This study hence suggests expanded research based on the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) to deeply examine the obstacles preventing consumers from using FinTech services. This research utilised an exploratory sequential mixed-method approach. Preliminary semi-structured interviews involving ten banking experts were undertaken to explore the barriers preventing consumers from using FinTech services. To get additional empirical support for the research concept, the study sequentially examined numerous components using a quantitative cross-sectional online survey involving 332 bank customers. The qualitative investigation highlighted six new barriers that consumers face when using FinTech. Through quantitative data analysis, the preliminary qualitative findings were largely verified. As far as the authors are concerned, this inquiry is the first to put forth a thorough model that takes into account organisational, technological, individual, and environmental aspects for addressing the problem of low FinTech usage. By incorporating several new factors, this study also expands the UTAUT. Additionally, it is one of the first studies to examine FinTech adoption employing a mixed-approach methodology.

1. Introduction

Banks and other classic financial institutions, which centralised market power in the financial system, have controlled financial services for decades. Nonetheless, the financial sector is now undergoing a disruptive structural transformation in the fourth industrial revolution (IR 4.0) era as a result of numerous technological advancements, together with the COVID-19 pandemic that has accelerated the process to stimulate big tech corporations [1,2] such as Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Alibaba to proactively participate in the financial system. This led to the conception of Financial Technology (FinTech), a financial innovation made possible by technology that affects financial markets, institutions, and the provision of financial services via the introduction of new business models, applications, procedures, or products [3].

FinTech is a cutting-edge innovation displacing traditional financial services and is rising to prominence globally. There have been over 12,500 start-ups in FinTech, with a global investment of USD 111.2 billion in H2′2022 [4]. The global FinTech market is anticipated to grow steadily and generate USD 324 billion in market value by 2026, with an increasing compound annual rate of 25.18% over the 2022–2027 forecasted period, due to the currently vast numbers of smart device users who prefer online transactions along with the evidence that FinTech implementation significantly boosts customer experience [5].

The significant advancements in information technology (IT) and their integration, including the internet of things, artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, and blockchain have allowed financial services firms to automate their business processes and fundamentally rationalise the financial services value chain with entirely new and inclusive products, services, processes, and business models that can effectively fulfil the needs and demands of users [6,7]. Academic studies back up the idea that FinTech services give consumers access to a dynamic ecosystem because they offer personalisation, flexibility, and simplicity of delivery at a reduced cost, which ultimately boosts productivity, profitability, and financial inclusion [4,7]. Besides its qualities that promote the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [8,9], FinTech can make financial businesses more sustainable by promoting green finance [10]. Additionally, FinTech potentially gives access to financial services to 1.6 billion people in emerging economies. By minimising expenditures and tax revenue leakage, it may boost the amount of loans made to people and businesses by USD 2.1 trillion while also enabling governments to save USD 110 billion annually. It is equally advantageous for financial service providers, who could sustainably increase their balance sheets by up to USD 4.2 trillion while saving USD 400 billion yearly in direct costs [11]. Substantial FinTech usage can enhance emerging economies’ GDP by USD 3.7 trillion by 2025, or 6% more than the status quo [11].

The government of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) continues to place a high premium on digital transformation. The UAE’s central bank established a FinTech unit in December 2020, emphasising its dedication towards establishing proper regulations, privacy and data protection, low carbon and green FinTech, and inclusive financial services, as well as towards developing a mature FinTech ecosystem [12]. The UAE is leading the MENA’s FinTech market, recording a high of USD 2.5 billion with investment growth of 64% reaching USD 819 million in 2022 [13]. The number of FinTech companies in the UAE is steadily rising. In 2022, there were 189 new licensed FinTech companies taking the total to 303, offering various financial services, including e-payments/transactions, e-wallet, blockchain/cryptocurrency, digital banking/neobanks, InsurTech, WealthTech, RegTech, crowdfunding, peer-to-peer insurance and lending platforms, remittance, and others [13]. Investors are now encouraged to help regional projects financially thanks to FinTech platforms, hence promoting UAE’s 2030 vision to become a regional and global hub for FinTech and contributing to the country’s overall economic growth [12].

Across the globe, FinTech services adoption has seen a remarkable increase among consumers from 16% in 2015 to 33% in 2017 and 64% in 2019, with the high adoption rate mainly in nations such as India and China [14]. However, the UAE has experienced a relatively poor consumer adoption rate, as low as 29% [15]. Despite the abundance of FinTech options that are accessible, adoption is highly selective, and only a small number of these have been a success. An example is e-payment services used by 84.3% of users, fuelling the growth in the usage of FinTech services [16]; others have shown lower adoption, including P2P money transfer [31%], robot advisor [27%], InsurTech [19%], crowdfunding [17%], and P2P insurance [10%], according to the national survey by Statista (2020) [15]. This duality presents the possible issues or obstacles in the use of FinTech. This study is thus inspired to look into the issues preventing clients in the UAE from utilising the existing FinTech services. The diffusion of FinTech is essential in preventing the most disadvantaged segments from significant financial losses, falling behind, attracting potential users, and retaining existing consumers.

For the purpose of marketing technology services in emerging areas, comprehension of the diffusion process is essential. Rogers [17] asserted that potential users’ readiness to embrace technological innovation is key to ensuring technology’s success and widespread adoption. Yet, limited comprehensive research findings have identified the factors influencing the use of FinTech [3]. Several studies examining the obstacles to the adoption and application of FinTech were found in the recent systematic literature analysis [18], most of which focused on the payment sector. Studies have been conducted to evaluate the FinTech phenomenon [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. They mainly concentrated on particular characteristics that are personal attributes of clients. However, they failed to take into account the individual, technological, organisational, and environmental characteristics that, when taken together, would provide a solid theoretical foundation for fully comprehending consumers’ perceptions [26,27]. The technology acceptance model (TAM) has been heavily cited in the literature by numerous researchers looking into how FinTech services are being adopted. The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT), which is regarded as a solid motivational basis characterising consumer behaviour towards technology, has received little empirical support [25]. Thus, a theoretical need was identified in the literature to broadly explore the challenges affecting consumers’ FinTech usage based on the UTAUT model. Contextually, the existing studies have been mainly experimented within East Asia. Their findings might not be practical in diverse Middle Eastern contexts such as the UAE due to the prevalence of distinctive consumer behaviour, cultural settings, social infrastructure, and economic indicators. As a result, it was determined that studies on the adoption of FinTech should be performed for each country. The majority of authors took a positivist approach to research designs by merely employing cross-sectional surveys to validate an altered research model. Their determinants were created by synthesising prior research and accepted hypotheses. As they ignored the mixed-method approach that merges the strengths of quantitative and qualitative approaches in a single study to determine the methodological contributions, most models were therefore primarily classified as restricted and tactical.

The study aimed to address the following research questions (RQs) in order to close the aforementioned research gaps:

RQ1: What challenges affect consumers’ usage of FinTech services in the UAE?

RQ2: What effects do individual, technological, organisational, and environmental factors have on consumers’ intention to use FinTech services?

RQ3: Is the UTAUT model relevant for explaining consumers’ use of FinTech services in the UAE?

Unlike the extant studies, this study essentially is a fresh attempt to bridge the identified theoretical, methodological, and contextual gaps by exploring the obstacles preventing consumers from using FinTech services using a mixed-method approach and extending the UTAUT framework in the UAE. The FinTech literature can benefit from the advancements made by this study. First, it facilitates identifying the numerous issues affecting the uptake of FinTech services among UAE consumers. Second, it employs and experimentally extends the UTAUT model in forecasting the uptake of FinTech services, particularly to the applicability and generalizability of the UTAUT in new contexts. Third, the study uses both qualitative and quantitative approaches in a mixed-method approach, thus paving the way for a clearer understanding of the intricate interrelationships between the new elements influencing the uptake of FinTech services. Lastly, the results of this study provide insightful perspectives for researchers and help managers and policymakers to create successful plans for influencing consumers’ digital usage behaviour.

2. Literature Review

2.1. FinTech: A Portmanteau of Finance and Technology

A new wave of technological innovations, known as FinTech, is regarded as a differentiating taxonomy that primarily defines the financial technology sectors in various activities, essentially concerning the enhancement of service quality via a heavy reliance on IT solutions [28]. Many definitions of FinTech have been given in the literature, although they do not differ considerably. It alludes to companies that operate beyond conventional financial services via the utilisation of technology, with business models that alter the provision of financial services [4]. As per the working definition of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), FinTech is a broad range of financial services that rely on digital channels for their delivery and access [29]. FinTech refers to cutting-edge financial solutions made possible by technological innovation. It is frequently used to refer to start-up businesses that provide these solutions. Still, it also includes established financial service providers such as banks and insurers to boost their competitiveness and improve financial functions and consumer behaviour [4,7]. As an umbrella term, FinTech is the application of digital technology to financial services [30], covering immense scopes of techniques, including data security and financial service delivery. In the current study, FinTech describes technology-related innovations used in designing and delivering financial services and products.

2.2. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

Using well-established theoretical frameworks drawn from various socio-cultural contexts, usage intentions and user behaviour have been studied. While the current ones have been and continue to be utilised, validated, modified, or criticised, new frameworks are being developed to address the shortcomings/insufficiencies present in the current ones [31]. The TAM and its derivatives (TAM2 and TAM3), the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), the Diffusion of Innovations Theory (DOI), and the UTAUT are prominent among the theories/models used for gaining insights into people’s and organisations’ likelihood to embrace, adopt, and employ technology. TAM-based and UTAUT models have been determined to be the most effective among these frameworks [32]. Owing to its highly explanatory and predictive components, the UTAUT was shown to be the most effective model for explaining technology adoption with 70% variance [33].

According to the systematic review [33], the UTAUT model is reliable for examining people’s adoption of IT in various fields. However, when attempting to describe how users embrace IT, particularly in consumer scenarios, the UTAUT model’s explanatory capacity may be constrained [34]. According to Venkatesh [35], the addition of new determinants could aid in broadening the UTAUT’s applicability in a consumer environment. In light of this, the primary contribution of the current study is not only to replicate it in a new setting but also to extend the UTAUT model by adding new individual, technological, organisational, and environmental determinants. This creates a solid foundation to thoroughly explain consumers’ intention to use FinTech in the context of emerging economies such as the UAE.

3. Research Methodology

The study technique was developed using the mixed-methods approach. A mixed-methods strategy minimises the weaknesses of both qualitative and quantitative methods while combining their advantages in a single study [35]. The various research procedures enable the researcher to accept, cross-validate, and verify findings within a single study [35,36]. Therefore, this study adopted an exploratory sequential mixed-methods approach to investigate the barriers preventing UAE’s consumers from using FinTech. In order to get a comprehensive understanding of the subject, the study first reviewed pertinent literatures. Using the information gathered during the preliminary stage of the semi-structured interviews, the authors identified the empirical codes that most likely serve as the foundation of the study. This made establishing a core set of variables and put the research in a broader context. A hypothesis was then developed for each empirical code to create the study’s final model. In order to gather further empirical evidence to support the theoretical framework, the study investigated the developed hypotheses via a quantitative cross-sectional survey using a larger sample.

3.1. Phase One: Qualitative Study

A preliminary qualitative study which examined the key elements influencing how consumers perceive FinTech was carried out through semi-structured open-ended interviews with UAE bank managers. Based on the study’s objectives, the researchers created a protocol for the interviews. In this case, study, the factors found in the interview transcripts were categorised using the inductive method. A hierarchical framework was used to develop the conceptualised interpretations, with the top-level notions serving as the primary factors of the study objective. Lastly, a theoretical narrative describes the framework underlying the explanation of these factors.

Focus group interviews served as the primary data-gathering method for this study. The main goal of qualitative research is to amass comprehensive knowledge about a subject. As advised by many qualitative scholars, a purposive sample strategy was utilised here to choose the suitable informants, namely the specialists, and to comprehend the studied phenomenon [35,36,37,38]. Most contemporary qualitative academics have noted that the researcher’s subjective assessment defines the sample size and that the researcher is aware of when the saturation point has been achieved [35,36,37,38]. When the material has reached the point of saturation, and no new themes are coming to light, the process can be terminated [36,38]. As such, the semi-structured interviews with ten individuals from varied positions and sites were sufficient in this study to accomplish saturation. The semi-structured interviews were conducted between November 2021 and February 2022, and each interview took about 45 to 60 min.

The transcriptions were analysed using Thematic Content Analysis (TCA), a qualitative method, to locate the codes related to the theoretical foundation, which served as the basis for the research. The steps outlined by Braun and Clarke [39] were used for the qualitative data analysis. These include conducting the interviews and recording them, listening to the taped interviews and transcribing them, getting participants to confirm the transcripts, coding the verified transcripts, naming and organising the codes, putting quotes and memos into the proper codes, analysing the results and producing outputs, and finally, putting the report into writing.

3.2. Phase Two: Quantitative Study

Based on the semi-structured interviews, several probable elements that might have influenced consumers’ adoption of FinTech were found. The proposed final model from the study was created using a set of hypotheses. After that, to evaluate the developed hypotheses, a quantitative cross-sectional survey was conducted among a larger sample of UAE consumers gathered via an online survey between April 2022 and August 2022. Two phases of the PLS-SEM in Smart PLS 3 were carried out to validate the results, i.e., the measurement model assessment to confirm the instrument’s accuracy and validity and the structural model assessment to test the study hypotheses. PLS-SEM was employed in this study due to its suitability in the exploratory phase of the theory building, prediction or expansion [40].

Meanwhile, power analysis determined the minimum sample size due to the lack of a sample frame. Based on Cohen’s (1988) [41] formula for identifying the most appropriate sample size, G*Power was utilised to determine the standardised significance criterion α, effect size (ES), statistical power (1-β), and quantity of indicators. By utilising G*Power for two tails, medium ES of 0.05, α of 0.05, power of 0.95, and ten predictors, it was found that at least 242 respondents were needed. However, for the purpose of generating more reliable outcomes, the researchers raised the sample size to 332.

To guarantee the validity of all the 53-question instruments, the measurement scales used in earlier studies were modified where needed to meet the setting of the current study. Multiple items with scales ranging from 1 for “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree” were used to measure each construct. Appendix A lists the survey questions and their sources. Despite the fact that the majority of people in the UAE are fluent in English, the original instruments were translated into Arabic by a certified multilingual translator. A second certified multilingual translator retranslated the Arabic version into English. Next, the semantic equivalence between the back-translated and original versions was examined. There were minor differences between the source text and the back-translated version. In addition, during the pre-test, the questionnaire was validated by two senior academic experts and one professional banker to detect any issues with phrasing, content, or ambiguity. As requested by the academic specialists, a pilot survey involving 50 bank customers was conducted. As the reliability of each construct was more than 0.70, the pilot test findings were deemed satisfactory [42,43,44].

4. Phase One: Qualitative Data Analysis and Findings

For the semi-structured interviews, the researcher contacted a number of banking professionals. Ten bankers from different sites in the UAE ultimately consented to take part in the study, which was enough to reach the point of saturation. In order to protect their privacy, the participants were designated as R1, R2, through to R10. The selection of the informants was based on their positions, professional backgrounds, and knowledge of the banking business and this study topic (Table 1).

Table 1.

Informants’ Professional Profiles.

Six new subthemes in line with the four predetermined themes were produced from the qualitative analysis: the individual attribute was denoted by consumers awareness and personal innovation, the organisational attribute was denoted by firm reputation, the technological attributes were represented by security and privacy and system quality, whilst the environmental attribute was denoted by governmental support (see Table 2). By asking the selected subject-matter experts to evaluate the data patterns with respect to the related themes, the researchers were able to validate the study. This demonstrated the degree to which the findings met the initial phase’s objective.

Table 2.

Summary of the Qualitative Phase Output.

5. Research Framework and Hypotheses Development

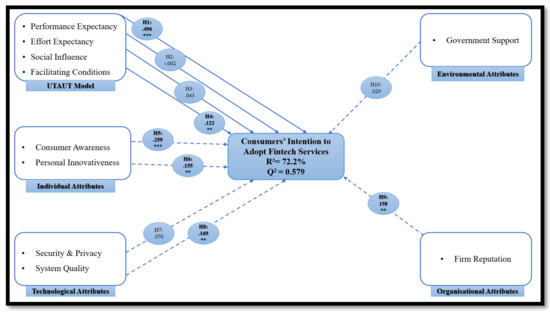

The final research framework shown in Figure 1 was developed based on the UTAUT model’s four core constructs as well as six additional factors identified during the qualitative data analysis, including consumer awareness, personal innovation, firm reputation, security and privacy, system quality, and governmental support. These factors were categorised under the four basic attributes of individual, technological, organisational, and environmental. This served as the foundation for investigating to fully explain consumers’ intention to use FinTech services. The next subsection discusses each of the variables proposed in this study and their most plausible connections.

Figure 1.

The Structural Model Results.

5.1. Original UTAUT Model

5.1.1. Performance Expectancy

A component of the UTAUT model, performance expectancy to predict consumers’ belief in the improvement of task implementation via the usage of technology [45]. It was also identified as the most effective predictor of user behavioural intention in a later revision (UTAUT2) [46]. Many researchers have paid close attention to performance expectancy [47,48,49,50,51]. According to these studies, it is a crucial concept in the analysis of improved information system usage. The degree to which FinTech meets customer expectations is essential to fully understand its usefulness [23,52,53]. Therefore, consumers may be more likely to use these services if they believe FinTech would significantly improve their financial performance. This study hypothesised that performance expectancy would affect consumers’ intention to use FinTech services in line with the assertion of the existing literature and the UTAUT model, which claimed that IT-oriented products or services boost job performance and enable efficient, useful, effortless, and timely transactions. This debate resulted in the hypothesis below:

H1:

There is a significant relationship between performance expectancy and consumers’ intention to use FinTech services.

5.1.2. Effort Expectancy

Effort expectancy determines users’ level of convenience when utilising certain information systems [45]. Regarding the influence of effort expectation on technological behaviour, prior literatures have reported a variety of contradictory findings. Numerous studies have found that consumers’ intentions are significantly influenced by effort expectancy [23,54,55]. Contrarily, it was asserted in other empirical research that it is not a substantial factor, such as in the adoption of e-learning [56], e-voting [57], mobile commerce [2], and green technology [58,59]. Particularly, contradictory findings have been reported in the context of FinTech. Rahim et al. [52] found an insignificant influence on consumer perception, which conflicts with the conclusion of Yeh et al. [53] who confirmed the relationship. These wildly divergent findings demonstrated the need to investigate how effort expectancies affect users’ intentions to use FinTech services. According to the UTAUT model, consumers might not hesitate to use valuable and convenient IT-based services when making financial transactions. This provided support for the second hypothesis, which proposed that consumers’ expectation of effort would influence their decision to use FinTech services:

H2:

There is a significant relationship between effort expectancy and consumers’ intention to use FinTech services.

5.1.3. Social Influence

Theories of social psychology stress the significance of social influence in shaping behaviour. According to Bandura and Walters’ [60] social learning theory, people can learn from one another by communicating with reliable contacts. In addition, the conflict elaboration theory of social impact proposed that an individual’s relationships with other group members should be considered while deciding whether to embrace or reject a certain technology [61]. Many theories and models of the adoption and use of technology, including the TRA, TBP, TAM, and UTAUT, contend that social influence is a key factor in determining a person’s behavioural intention. Social influence is the degree to which an individual’s use of technology is influenced by the opinions of others [45]. Despite not supporting technology usage, the theory underlying social influence holds that such people will nonetheless utilise technology if they perceive that it will boost their reputation among their peers [62]. Numerous empirical researchers have found that social influence has a significant impact on user behaviour [26,63,64,65,66]. However, subsequent studies debunked this notion as they found no conclusive evidence to the claim [67,68,69,70]. Likewise, contradictory findings about the function of social influence have been reported in FinTech research. Some studies supported the beneficial effects of social influence [23,52,53,59,71]. Others, however, claimed that it was not a significant factor in determining how consumers felt [58,59,72]. These contradictory results suggest that social influence is highly context-dependent, which motivates the review of the study’s setting. According to the UTAUT model, it can be concluded that some technology services are in style, lending support to the notion that consumers’ intentions to use FinTech services are influenced by the social influence construct:

H3:

There is a significant relationship between social influence and consumers’ intention to use FinTech services.

5.1.4. Facilitating Conditions

The provision of technical resources needed to facilitate the deployment of a certain technology is referred to as a facilitating condition [45]. According to the UTAUT, facilitating condition is a construct that reflects an individual’s sense of control over their behaviour [73]. Although the extended UTAUT2 corroborated this direct effect, the original UTAUT did not indicate a direct relationship between facilitating conditions and behavioural intention [46]. The research emphasised the significance of favourable circumstances as a critical indicator of intention to employ various technologies [50,74,75,76]. There is still a lack of data from the context of the UAE, a Middle Eastern country which is socially and economically distinct. Practically, facilitating conditions refer to when consumers have adequate supporting resources such as the expertise to embrace FinTech services, easy Internet access, the necessary smart equipment, and expert advice, allowing them to gain insightful ideas. Consequently, the following hypothesis was put forth:

H4:

There is a significant relationship between facilitating conditions and consumers’ intention to use FinTech services.

5.2. Individual Attributes

5.2.1. Consumer Awareness

The acceptance of innovations requires awareness [77]. The more knowledge is offered on technology properties, innovation is expected to rise [17]. People will eventually become more aware of and driven to support a particular service if they are well-informed about it [78]. A technology’s acceptability is hampered by people’s ignorance of its advantages, limitations, and benefits [79,80]. Numerous academics have emphasised how awareness might affect consumers’ behavioural intention [71,81,82,83,84]. This suggests that offering additional details about the precise characteristics of FinTech services may have a favourable impact on the adopters’ choices. It is expected that consumers with high levels of awareness would be more likely to accept innovative FinTech by taking into account the perception of the informants in the qualitative study as well as the discussion presented above. Consequently, it is hypothesised that:

H5:

There is a significant relationship between consumer awareness and their intention to use FinTech services.

5.2.2. Personal Innovativeness

According to diffusion theory, adopters have positive expectations about new technologies [85]. Positive attitudes toward technology adoption influence user satisfaction favourably [86], thus encouraging innovation and improving technology usage behaviour [87]. In the sphere of technology, Agarwal and Prasad [88] established the idea of personal innovativeness, i.e., an individual’s disposition to use a certain new technology. Although it was initially proposed as a moderating element [88], personal innovativeness has been shown to be a crucial antecedent in adopting innovations [89]. Numerous empirical investigations have found that a person’s capacity for innovation influences their behaviour [70,90]. This suggests that highly inventive people are better disposed to using a variety of FinTech services. The following hypothesis was developed based on the informants’ expectations in the qualitative inquiry and the prior literatures:

H6:

There is a significant relationship between personal innovativeness and consumers’ intention to use FinTech services.

5.3. Technological Attributes

5.3.1. Security and Privacy

Security and privacy have become more crucial due to new technologies’ expanding capacity for information processing and integration into consumers’ everyday lives. Due to their growing sense of insecurity on how their personal data are being collected and handled [91], consumers find it difficult to accept their lack of control over their behaviour [92]. Yoon et al. [93] emphasised that security and privacy are conditions for technology adoption, and further highlighted the quantitative significance of this issue. Positive perceptions of security and privacy are associated with a better likelihood to adopt a new financial system [94] and services [26], higher e-satisfaction [95], user trust [2,24], and better service selection [96]. Meanwhile, Chatterjee [97] and Bouteraa et al. [58] asserted the possibility that consumers are not concerned about security and privacy when using new technology in some settings. The following hypothesis was developed in light of the requirements for high-security measures in FinTech and the expectations set forth in the qualitative phase of the study:

H7:

There is a significant relationship between security and privacy and consumers’ intention to use FinTech services.

5.3.2. System Quality

In both the original DeLone and McLean Information Systems Success Model (D&M model) [98] and its amended version [99], system quality is put forth as one of the most strategic elements. It is essential for obtaining the production output associated with an information processing system. The technological level of a system’s information production success determines its quality [98]. This pertains to the software and data elements and measures the system’s technical soundness [100]. Customer impressions of information retrieval and service delivery are key indicators of system quality [101]. Users may require certain features of system quality, such as usability, availability, dependability, adaptability, accessibility, and response time [99]. The body of research highlights the significance of system quality as a key indicator of the desire to utilise a variety of technologies [102,103,104,105,106]. This implies that higher system quality encourages more consumers to use the services. According to the expectations of the informants described in the qualitative study and the aforementioned literature, FinTech necessitates a thorough system structural design, a quick response time, and reliability to perform various operations in a flexible process without interruptions. As such, the hypothesis below was developed:

H8:

There is a significant relationship between system quality and consumers’ intention to use FinTech services.

5.3.3. Organisational Attributes

Firm Reputation

One of a company’s most important intangible assets is “reputation” which is built through time through the establishment of its credibility and believability [107] and of which primarily influences the behaviour of its clients [108]. Based on previous behaviour and anticipated future outcomes, an organisation’s corporate reputation determines whether it will be preferred by stakeholders over its main competitors [109]. Consumer decision-making has long placed a premium on corporate reputation [107]. When creating their overall perceptions, consumers give a lot of weight to a company’s reputation [110,111,112,113,114]. Many studies have shown the importance of reputation in predicting technological adoption [115,116,117]. This means that customer behaviour regarding a company’s services is formed based on the company’s honesty, goodwill, and capacity to provide efficient, advantageous, and trustworthy services. Nevertheless, little attention has been paid to how a company’s reputation may affect FinTech usage. In line with the expectations stated in the qualitative investigation and the existing literature, this study hence hypothesised that:

H9:

There is a significant relationship between a firm reputation and consumers’ intention to use FinTech services.

5.4. Environmental Attributes

Government Support

The government has the ability to improve service credibility and reliability by promoting the application of technology in financial innovations and making infrastructural investments. Governmental provision drives consumers’ sense of security when utilising financial services [118]. A strong correlation between government funding and consumers’ adoption of innovation has been discovered via empirical studies [118,119,120,121]. However, several studies also claim the non-significance of governmental support as a factor in this context [122,123,124]. This suggests that the level of governmental support varies by country and environment. There is, however, a scarcity of research on the connection between governmental support and consumers’ intention to use FinTech services in the UAE. Based on all the above, this study hence hypothesised that:

H10:

There is a significant relationship between governmental support and consumers’ intention to use FinTech services.

6. Phase Two: Quantitative Data Analysis and Results

6.1. Sample of Study

In order to identify any missing values, descriptive statistics analysis was used with IBM-SPSS; the findings revealed none. However, out of the 338 cases, six were identified to be multivariate outliers and therefore removed [125]. This process was performed using the conventional method for detecting multivariate outliers, which involves computing the squared Mahalanobis distance at p < 0.001 for each case in the dataset [126]. Ultimately, for the actual data analysis, 332 cases were used. Table 3 summarises the demographic statistics. Harman’s single-factor test was used to detect common method bias typically occurring in survey data. A value of 37% was attained, and as it was lower than the threshold value of 50%, it was concluded that common method bias did not occur in the data [127].

Table 3.

Sample’s Demographic Description N = 332 [100%].

6.2. Assessment of Measurement Model

The measurement model assessment entails the evaluation of reliability (composite reliability (CR)), convergent validity (factor loadings and average variance extracted or AVE), and discriminant validity (Hetrotrait-Monotrait (HTMT)) [42]. Table 4 presents the results for the factor loadings, AVE, and CR, namely 0.70, 0.5, and 0.7, correspondingly [42,43,44,128].

Table 4.

Summary Results of Convergent Validity and Reliability.

HTMT ratios were used to assess discriminant validity. Table 5 presents the results, i.e., HTMT values of 0.85 and below for all the constructs [129]. This means that there are no discriminant validity issues in the dataset, thus confirming the validity of the measurement model.

Table 5.

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT).

6.3. Assessment of Structural Model

Although discriminant validity had been identified in the evaluation of the outer model, lateral collinearity problems could result in statistical instability and/or unreliable conclusions [130]. This issue was hence examined. VIF ≥ 5 suggests possible collinearity problems [43,44,128,131]. As shown in Table 6, the results support the assertion that multi-collinearity had no impact on the outcomes because all values VIF < 5.

Table 6.

Structural Model Results.

Next, the structural model assessment was conducted for hypothesis testing. Bootstrapping was conducted using 5000 iterations following the suggestion of Hair et al. [128]. The results are presented in Table 6 and Figure 1. An R² value of 72.2% was generated, explaining the substantial variance in behavioural intention, fulfilling the previously set [43,44,128,131]. Additionally, determined was the effect size [ƒ²], whereby a majority of the variables were found to have a small to medium effect based on Cohen’s criteria [132]. The result of the predictive relevance (Q2) for the endogenous construct is larger than the null (Intention: Q2 = 0.579) [128].

This research also examined the PLS predict as a validation of the model’s predictive relevance. PLS predict was employed to calculate the case-level predictions of PLS predict whereby k = 10, following the suggestions of Hair et al. [42] and Shmueli [43]. The Q² predict values were shown to be above zero (Q² predict > 0), suggesting that all the indicators had outperformed the Linear Model (LM) benchmark. This allowed for the RMSE values and naïve LM benchmark to be compared. The PLS-SEM and LM results’ comparison showed that indicators generated smaller prediction errors in comparison to the LM (PLS-SEM < LM) (see Table 7), suggesting the model’s medium predictive power [43]. This means that the model can predict responses accurately utilising out-of-sample data and generating testable predictions.

Table 7.

Results of PLS Predict.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

7.1. Meta-Inference

Meta-inference was used in conjunction with the bridge technique to reconcile the qualitative and quantitative data in order to evaluate the study’s conclusions [133,134]. According to the qualitative data study, consumer awareness and individual inventiveness are important personal elements that might accelerate the acceptance of FinTech services. The qualitative findings also suggested that the technical aspects of FinTech might operate as impediments, whereas system quality, security, and privacy may have the greatest bearing. The informants also emphasised that the organisational, motivational forces or barriers for consumers were constrained by their value judgements of the features of firms (i.e., reputation). Additionally, it was determined that important environmental constraints impacting consumers’ propensity to use FinTech services included government-related policies, regulations, and incentives. The quantitative data analysis mostly supported the preliminary qualitative findings, which revealed that consumer awareness, innovation, system quality, and reputation of FinTech providers have a substantial influence on consumers’ inclination to use FinTech services.

Meanwhile, the effects of governmental support, as well as security and privacy, were negligible. Accordingly, the majority of the qualitative findings could be generalised using quantitative research according to the study’s findings, which suggests that the mixed-method approach successfully bridges the qualitative and quantitative research gaps and synchronises the advantages of both research methodologies. Cross-referencing the empirical results in both research methodologies is beneficial to deepen comprehension of the specific research issue.

7.2. Discussion

This study shows that the usefulness of FinTech services in managing finances, ensuring efficiency, and saving time (i.e., performance expectancy), together with the accessibility of the necessary technical resources for users (i.e., facilitating conditions), could significantly increase consumers’ intention to use FinTech services. The underlying cause behind such a result is the novelty of such service in the culture of the UAE, where most errands are preferred to be served in a traditional manner from physical locations. These findings are consistent with the UTAUT paradigm and earlier research [23,52,58,59]. Effort expectancy was insignificant, in contrast to the UTAUT model’s assertion. This means that clients do not typically evaluate the significance of FinTech services based on their practicality, simplicity of use, interactivity, or competence. This behaviour may be attributed to reluctance and a lack of creativity when trying new services. These results may also be linked to different societal characteristics and principles influencing people’s perceptions [135]. Likewise, this study found the negligible impact of social influence. This might be explained by the users’ perception of financial concerns as a solitary and private activity, which justifies their sparse information sharing with peers and lessens the effect of peer pressure. Another reason for this finding is that the majority of the sampled respondents were young adults (18 to 39 years old), i.e., members of Gen Y who were born and raised in the technological era. This generation differs from Gen X in that it is more “self-directed” [70]. These conclusions suggest that the UTAUT model is relevant for explaining consumers’ use of FinTech services in the UAE.

This study’s two investigation phases demonstrated that consumer knowledge strongly influences consumers’ intention to use FinTech services. This indicates that empowered individuals may find them practical for managing their financial tasks. The use intention of a consumer would be positively influenced by prior information and educated curiosity regarding the existence, objectives, and numerous benefits of FinTech. This outcome is in line with past studies [81,82,83,136]. This result signifies that people are likely to be aware and find it meaningful to use FinTech services as it would benefit them in managing their financial tasks efficiently.

The qualitative and quantitative findings suggest that clients with higher degrees of inventiveness should have more favourable attitudes about FinTech services with a significant predictive relevance and substantial effect size. Hence, personal innovativeness is a significant barrier for consumers to use FinTech services, leading to poor uptake. These findings suggest that less innovative users may not prefer the new services as they are a relatively creative and advanced approach that is technologically different from other traditional banking methods. The reason for such behaviour might be the lack of understanding about the services, lack of an innovation mindset, uncertainty about the technology itself, fear of failing, and the time and effort that has to be spent to understand and master those innovative services. This conclusion backs the findings of previous research [70,90].

Security and privacy, according to bank specialists, are crucial for increasing consumers’ intentions to use FinTech services. The consumers did not, however, seem to share this impression throughout the quantitative phase, indicating that security and privacy issues did not rank highly with UAE consumers. The consumers’ upbeat opinions might be linked to the strict secrecy regulations and the reliable framework of the UAE’s financial sector, which is one of the most renowned and well-established in the world. Additionally, the idea of desensitisation, whereby society is used to living and working in a vulnerable environment, may be connected to decreased customer anxiety about impending security dangers and privacy violations. The consumers, on the other hand, were apprehensive about system quality. It became clear that they are drawn to a system’s capabilities and dependability. This is in line with the assertion of existing literature, which showed that when a technology system’s quality is improved, customer perception is significantly affected [102,103,104,105]. In both study phases, it was also shown that a company’s reputation has a substantial influence on consumers’ intentions to use FinTech. This suggests that having a high reputation indicates that a company offers dependable services due to its integrity and goodwill. Consumers today greatly rely on an organisation’s reputation in the market because there are more possible negative implications of choosing the wrong service providers. Customer intent is, therefore, driven mainly by a company’s prestige in the marketplace. This backs up the argument made in the literature that corporate reputation is an intangible organisational driver of technology adoption [116,117,137].

Furthermore, the bank professionals revealed throughout the qualitative phase that governmental support is an environmental factor which improves clients’ inclination to use FinTech services. The consumers, however, did not believe that the UAE government’s involvement had changed their intentions. This could be due to the fact that the governmental measures have not been successful or that the users believe that the measures have no effect on their decision to utilise such services.

7.3. Theoretical Implication

The empirical results of this study significantly advance academic knowledge on how consumers use FinTech services. Firstly, the study looked at six new elements that could explain the difficulties faced by clients in the UAE when using FinTech services. Secondly, the study increased the UTAUT model’s relevance and reliability in justifying the uptake of FinTech services in the UAE. Third, the study provided an overview of the important UTAUT factors influencing Emirati consumers’ acceptance of FinTech services. The model’s ability to explain a large amount of variance demonstrates the UTAUT framework’s applicability and effectiveness to this study. It is noteworthy that the main contributions not only replicate the UTAUT model in a new environment but also considerably advance the theory by integrating six new critical components. The PLS predict analysis demonstrated that the study’s model had medium predictive power as a broader theoretical contribution. This suggests that the model may produce testable predictions and reliably forecast reactions from beyond the sample.

Through the use of two complimentary analytical techniques, TCA and PLS-SEM, this research adds to the body of existing FinTech literature. By putting out six fresh combinations of obstacles preventing the use of FinTech services, TCA made a significant contribution to the findings. Additionally, the PLS-SEM results demonstrated the overall impacts of the newly added factors and UTAUT variables on the uptake of FinTech services. The subsequent findings supported the hypothesis that some variables, which were unimportant in the PLS-SEM analysis, could encourage the use of FinTech when combined with other variables.

7.4. Practical Implications

The study’s findings can assist scholars and policymakers in better understanding the effects of FinTech. The study can serve as a useful resource in creating effective policies that aim to maximise the advantages for mass consumers, service providers, and the national economy. The study explored and discussed how various individual, technological, organisational, and environmental attributes affect the intention of consumers to use FinTech services. The study offers a model for practitioners by better describing the actual difficulties that their clients face when utilising FinTech services. In order to ensure a smooth transition to digital consumer behaviour, it offers a robust framework for policy design and the planning and coordination of development strategies.

According to the study results, FinTech service providers in the UAE should focus less on social influence and more on the unique characteristics of their consumers, such as awareness and encourage their innovativeness to boost their perceptions via direct marketing. In order to maintain consistency in quality, FinTech providers should focus on providing helpful, accessible, quick, convenient, functional, and flexible services instead of focusing on security and privacy precautions, which are the areas that consumers in the UAE care about the least. Additionally, a company should maintain a strong reputation in the marketplace instead of seeking governmental backing because this intangible asset is essential for luring consumers to use FinTech services.

As practical incentives to stimulate the use of FinTech services, potential users would be offered practical financial services delivery channels in the shape of pleasant and quick service quality combined with strong security and reliability at more affordable costs. FinTech embracing will also enable FinTech companies to lower high operational expenses and avoid the waste associated with traditional processes. Economic improvements, digitalisation, social advantages, and sustainability goals are other incentives for using FinTech.

7.5. Limitations and Future Directions

To give the necessary insight for particular scenarios, this study primarily investigated the idea of FinTech services from a demand viewpoint (consumers). However, because one study cannot address all of these difficulties at once, it did not test the idea from the supply side. Hence, this study suggests that future research looks into the obstacles to FinTech adoption from the standpoint of FinTech providers. A deeper understanding of consumer behaviour could also be attained by including the moderating role of demographic parameters such as gender and age. Re-investigating the study’s research model in diverse industrial segments such as hospitality, healthcare, or education, and in other contexts such as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) or the Developing-8 (D-8) nations which have similar development indicators to the UAE’s, could help to further validate the conclusions of this study. The study is limited to a geographically specific sample, i.e., the UAE. A noteworthy suggestion for future directions is to conduct a comparative study that compares the results obtained in this study with similar studies conducted, for example, in the EU, the USA, or other parts of the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.B.; methodology, M.B.; validation, M.B., B.C., N.L. and A.A; formal analysis, M.B. and N.L.; resources, M.B. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B, B.C., N.L. and A.A.; administration, B.C.; funding acquisition, B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Universiti Malaysia Sabah.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data and estimation commands that support the findings of this paper are available upon request from the first and corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Intention: Source [45,65,76] | |

| IN 1 | I intend to use fintech services in the future |

| IN 2 | I predict I would use fintech services in the future |

| IN 3 | I plan to use fintech services in the future |

| IN 4 | I believe it is worthwhile for me to use fintech services |

| IN 5 | I am very likely to use fintech services in the future |

| IN 6 | I am interested to use fintech services |

| Performance Expectancy: Source [45] | |

| PE 1 | Using fintech services can make my financial transactions more efficient |

| PE 2 | Using fintech services can save my time in conducting financial transaction |

| PE 3 | Using fintech services can make my financial transactions more convenient |

| PE 4 | Using fintech services can be useful in managing my finances |

| Effort Expectancy: Source [45] | |

| EE 1 | Learning to use fintech services is easy for me |

| EE 2 | Becoming skilful at using fintech services is easy for me |

| EE 3 | Interaction with fintech services is easy for me |

| EE 4 | Overall, I think fintech services are easy to use |

| Social Influence: Source [45] | |

| SI 1 | People who are important to me think that I should use fintech services |

| SI 2 | People who are familiar with me think that I should use fintech services |

| SI 3 | People who influence my behaviour think that I should use fintech services |

| SI 4 | It is trendy to use fintech services |

| Facilitating Conditions: Source [45,72] | |

| FC 1 | I have the knowledge necessary to use fintech services |

| FC 2 | I have the resources necessary to use fintech services |

| FC 3 | Using fintech services suits my living environment |

| FC 4 | Using fintech services is compatible with my transactions |

| FC 5 | Company assistance is available when using fintech services |

| Consumer Awareness: Developed by the authors | |

| AW 1 | I am aware of the existence of fintech services |

| AW 2 | I am aware of the concept of fintech services |

| AW 3 | I know the purpose of fintech services |

| AW 4 | I know the benefits of using fintech services |

| AW 5 | In general, I have enough information about fintech services |

| Personal Innovativeness: Source [88] | |

| PI 1 | If I hear about new technology, I look for ways to experiment with it |

| PI 2 | I am usually the first to try new information technologies Among my peers |

| PI 3 | In general, I am not hesitant to try out new information technologies |

| PI 4 | I like to experiment with new information technologies |

| Security & Privacy: Source [92] | |

| S&P 1 | I believe that fintech services have adequate security measures |

| S&P 2 | I believe that fintech services are able to protect my privacy |

| S&P 3 | I feel safe about using fintech services |

| S&P 4 | Security is important to me in using fintech services |

| System Quality: Source [98,106] | |

| SQ 1 | Fintech services have a comprehensive design |

| SQ 2 | Fintech services have a fast transaction processing time |

| SQ 3 | Fintech services are reliable |

| SQ 4 | Fintech services can be used at anytime |

| SQ 5 | Fintech services have good functionality relevant to my transaction |

| SQ 6 | Fintech services keep error-free transactions |

| Firm Reputation: Source [107,113] | |

| FR 1 | This Fintech firm is reputed to keep promises for customers |

| FR 2 | This Fintech firm has a good reputation in the financial market |

| FR 3 | This Fintech firm has a positive reputation among customers |

| FR 4 | The Fintech firm is well-known to the public |

| FR 5 | This Fintech firm is reputed for transactions with customers |

| Government Support; Source [65,121] | |

| GS 1 | The government encourages the use of fintech services |

| GS 2 | The government promotes the use of fintech services |

| GS 3 | The government provided incentives to adopt fintech services |

| GS 4 | The government guarantees the solidity of fintech services |

| GS 5 | The government encourages new innovations in fintech services |

References

- Fulop, M.T.; Magdas, N. Opportunities and Challenges in the Accounting Profession Based on the Digitalization Process. Eur. J. Acc. Financ. Bus. 2022, 10, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, U.; Fülöp, M.T.; Tiron-Tudor, A.; Topor, D.I.; Căpușneanu, S. Impact of Digitalization on Customers’ Well-Being in the Pandemic Period: Challenges and Opportunities for the Retail Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). Financial Stability Implications from FinTech; Financial Stability Board (FSB): Basel, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG. Pulse of Fintech; KPMG: Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Market Data Forecast. Global Fintech Market Research Report; Market Data Forecast: Hyderabad, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Sahni, M.M.; Kovid, R.K. What drives FinTech adoption? A multi-method evaluation using an adapted technology acceptance model. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 1675–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschmann, T. Fintech. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2017, 59, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittini, J.S.; Rambaud, S.C.; Pascual, J.L.; Moro-Visconti, R. Business Models and Sustainability Plans in the FinTech, InsurTech, and PropTech Industry: Evidence from Spain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puschmann, T.; Hoffmann, C.H.; Khmarskyi, V. How Green FinTech Can Alleviate the Impact of Climate Change—The Case of Switzerland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP]. Fintech and Sustainable Development: Assessing the Implications; United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP]: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Manyika, J.; Lund, S.; Singer, M.; White, O.; Berry, C. Digital Finance for All: Powering Inclusive Growth in Emerging Economies; McKinsey & Company: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fintech Middle East. Fintech News Middle East: UAE Fintech Report 2021; Fintech Middle East: Abu Dhabi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UAE Ministry of Economy. Investing in Fintech in the UAE 2022 Dec. Available online: https://www.moec.gov.ae/documents/20121/0/2021+06+13+Fintech+Investment+Heatmap+_WhyUAE+-%28003%29.pdf/8c954153-89f4-27d9-016d-5d51f8ef375f?t=1644223394689 (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- EY Global FinTech Adoption Index. Global FinTech Adoption Index 2019; EY Global FinTech Adoption Index: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Share of Customers Who Adopted Financial Technology Solutions in the United Arab Emirates in 2020; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Said, R.; Najdawi, A.; Chabani, Z. Analyzing the Adoption of E-payment Services in Smart Cities using Demographic Analytics: The Case of Dubai. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2021, 6, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M. Diffusion of Innovation, 3rd ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J.; Rani, V. Journey of Financial Technology (FinTech): A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. In Exploring the Latest Trends in Management Literature; Review of Management Literature; Rana, S., Sakshi, Singh, J., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Nangin, M.A.; Barus, I.R.G.; Wahyoedi, S. The Effects of Perceived Ease of Use, Security, and Promotion on Trust and Its Implications on Fintech Adoption. J. Consum. Sci. 2020, 5, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Raza, S.A.; Khamis, B.; Puah, C.H.; Amin, H. How perceived risk, benefit and trust determine user Fintech adoption: A new dimension for Islamic finance. Foresight 2021, 23, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.T.; Nguyen, L.T.H. Consumer adoption intention toward FinTech services in a bank-based financial system in Vietnam. J. Financ. Regul. Compliance 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Sharma, P. A study of Indian Gen X and Millennials consumers’ intention to use FinTech payment services during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Model. Manag. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Nashwan, S.A. Toward diffusion of e-Zakat initiatives amid the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Foresight 2022, 24, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fülöp, M.T.; Topor, D.I.; Ionescu, C.A.; Căpușneanu, S.; Breaz, T.O.; Stanescu, S.G. Fintech accounting and industry 4.0: Future-proofing or threats to the accounting profession? J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2022, 23, 997–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhwaldi, A.F.; Alharasis, E.E.; Shehadeh, M.; Abu-AlSondos, I.A.; Oudat, M.S.; Bani Atta, A.A. Towards an Understanding of FinTech Users’ Adoption: Intention and e-Loyalty Post-COVID-19 from a Developing Country Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M.; Hisham, R.R.I.R.; Zainol, Z. Exploring Determinants of Customers’ Intention to Adopt Green Banking: Qualitative Investigation. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2021, 16, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, A.; Rottman, J.W.; Lacity, M.C. A Review of the Predictors, Linkages, and Biases in IT Innovation Adoption Research. J. Inf. Technol. 2006, 21, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, K.; Qiu, M.; Sun, X. A survey on FinTech. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2018, 103, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Leckow, R.; Haksar, V.; ManciniGriffoli, T.; Rochon, C.; Tourpe, H. Fintech and Financial Services: Initial Considerations; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Fintech and the Future of Finance—Overview; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Izuagbe, R.; Ifijeh, G.; Izuagbe-Roland, E.I.; Olawoyin, O.R.; Ogiamien, L.O. Determinants of perceived usefulness of social media in university libraries: Subjective norm, image and voluntariness as indicators. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2019, 45, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachak, A.; Kuziemsky, C.; Petersen, C. Beyond TAM and UTAUT: Future directions for HIT implementation research. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 100, 103315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, N.; Ladhari, R.; Chaouali, W. Mobile banking adoption: A systematic review. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 39, 214–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.; El-Masri, M.; Ali, M.; Serrano, A. Extending the UTAUT model to understand the customers’ acceptance and use of internet banking in Lebanon. Inf. Technol. People 2016, 29, 830–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; 371p. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R.J. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach, 8th ed.; Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; 432p. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, W.; Poth, C. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–646. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2012; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Los Anglos, CA, USA; Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Ray, S.; Velasquez Estrada, J.M.; Chatla, S.B. The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4552–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu. X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41410412 (accessed on 3 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Wiafe, I.; Koranteng, F.N.; Tettey, T.; Kastriku, F.A.; Abdulai, J.D. Factors that affect acceptance and use of information systems within the Maritime industry in developing countries. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2019, 22, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Arora, N. Investigating consumer intention to accept mobile payment systems through unified theory of acceptance model. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 9, 88–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, N.H.; Tham, J.; Azam, S.M.F.; Khatibia, A.A. Analysis of customer behavioral intentions towards mobile payment: Cambodian consumer’s perspective. Accounting 2020, 6, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M.; Raja Hisham, R.R.I.; Zainol, Z. Islamic Banks Customers’ Intention to Adopt Green Banking: Extension of UTAUT Model. Int. J. Bus. Technol. Manag. 2020, 2, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, F.; Jacobs, M.; Pather, S. Barriers for User Acceptance of Mobile Health Applications for Diabetic Patients: Applying the UTAUT Model; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, N.F.; Bakri, M.H.; Fianto, B.A.; Zainal, N.; Hussein Al Shami, S.A. Measurement and structural modelling on factors of Islamic Fintech adoption among millennials in Malaysia. J. Islam. Mark. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.C.; Yu, M.C.; Liu, C.H.; Huang, C.I. Robo-advisor based on unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjaluoto, H.; Shaikh, A.A.; Leppäniemi, M.; Luomala, R. Examining consumers’ usage intention of contactless payment systems. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 38, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdullah, J.H.; van Lunen, B.L.; Claiborne, D.M.; Daniel, S.J.; Yen, C.; Gustin, T.S. Application of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model to predict dental students’ behavioral intention to use teledentistry. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 84, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Masri, M.; Tarhini, A. Factors affecting the adoption of e-learning systems in Qatar and USA: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2). Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2017, 65, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, I.K. Impact of Performance Expectancy, Effort Expectancy, and Citizen Trust on the Adoption of Electronic Voting System in Ghana. Int. J. Electron. Gov. Res. 2020, 16, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M.; Raja Hisham, R.R.I.; Zainol, Z. Bank Customer Green Banking Technology Adoption: A Sequential Exploratory Mixed Methods Study. In Handbook of Research on Building Greener Economics and Adopting Digital Tools in the Era of Climate Change; Ordóñez de Pablos, P., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 64–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M.; Raja Rizal Iskandar, R.H.; Zairani, Z. Challenges affecting bank consumers’ intention to adopt green banking technology in the UAE: A UTAUT-based mixed-methods approach. J. Islam. Mark. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mugny, G.; Butera, F.; Sanchez Mazas, M.; Pérez, J.A. Judgements in conflict: The conflict elaboration theory of social influence. Perception evaluation interpretation. Swiss Monogr. Psychol. 1995, 3, 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavian, C.; Guinaliu, M.; Lu, Y. Mobile payments adoption—Introducing mindfulness to better understand consumer behavior. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1575–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saedi, K.; Al-Emran, M.; Ramayah, T.; Abusham, E. Developing a general extended UTAUT model for M-payment adoption. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.; Rahim Abdul Rahman, A.; Laison Sondoh, S.; Magdalene Chooi Hwa, A. Determinants of customers’ intention to use Islamic personal financing. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2011, 2, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, N.; Lada, S.; Chekima, B.; Abdul Adis, A.A. Exploring Determinants Shaping Recycling Behavior Using an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model: An Empirical Study of Households in Sabah, Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Shah, N.; Ali, M. Acceptance of mobile banking in Islamic banks: Evidence from modified UTAUT model. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 10, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handarkho, Y.D. Impact of social experience on customer purchase decision in the social commerce context. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2020, 22, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, E.; Loisa, J. The Intention and Use Behaviour of the Mobile Banking System in indonesia: UTAUT Model. Technol. Rep. Kansai Univ. 2020, 62, 2757–2767. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, G.A.; Tiew, L.Y.; Tang, J.; Goh, Y.N.; Thurasamy, R. The adoption of cryptocurrency as a disruptive force: Deep learning-based dual stage structural equation modelling and artificial neural network analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M.; Al-Aidaros, A.H. The Role of Attitude as Mediator in the Intention to Have Islamic Will. Int. J. Adv. Res. Econ. Financ. 2020, 2, 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Nisha, N.; Raza, S.A. Customers’ Perceptions of Green Banking: Examining Service Quality Dimensions in Bangladesh; Green Business; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 1071–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Brown, S.A.; Maruping, I.M.; Bala, H. Predicting Different Conceptualizations of System Use: The Competing Roles of Behavioral Intention, Facilitating Conditions, and Behavioral Expectation. MIS Q. 2008, 32, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tao, D.; Yu, N.; Qu, X. Understanding consumer acceptance of healthcare wearable devices: An integrated model of UTAUT and, T.T.F. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 139, 104156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, D.; Tabibi, Z.; van Wee, B. Factors influencing the acceptance and use of a bicycle sharing system: Applying an extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2020, 8, 1212–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Joshi, H. Consumer attitude and intention to adopt mobile wallet in India—An empirical study. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1590–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiltinand, J.P.; Donnelly, J.H. The use of product portfolio analysis in bank marketing planning. In Management Issues for Financial Institutions; Shanmugam, B., Ed.; University of New England: Biddeford, ME, USA, 1983; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Lujja, S.; Mohammed, M.O.; Hassan, R. Islamic banking: An exploratory study of public perception in Uganda. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2018, 9, 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, R.R.; Alathur, S. Determinants of individuals’ intention to use mobile health: Insights from India. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2019, 13, 306–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanya, F.C. Institutional repository: Access and use by academic staff at Egerton University, Kenya. Libr. Manag. 2017, 38, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteraa, M. Barriers Factors of Wasiyyah (Will Writing): Case of BSN Bank. IBMRD’s J. Manag. Res. 2019, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, S.S.; Verma, S.; Singh, V. Exploring the intention to use M-payment in India. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2019, 13, 276–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Sinha, N. How perceived trust mediates merchant’s intention to use a mobile wallet technology. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baabdullah, A.M. Factors Influencing Adoption of Mobile Social Network Games (M-SNGs): The Role of Awareness. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, M. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Ullah, I. Emotional intelligence of library professional in Pakistan: A descriptive analysis. PUTAJ-Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 21, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.; Masrek, M.N.; Mahmood, K. The relationship of personal innovativeness, quality of digital resources and generic usability with users’ satisfaction. Digit. Libr. Perspect. 2019, 35, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Prasad, J. A Conceptual and Operational Definition of Personal Innovativeness in the Domain of Information Technology. Inf. Syst. Res. 1998, 9, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.; Angriawan, A.; Summey, J.H. Technological opinion leadership: The role of personal innovativeness, gadget love, and technological innovativeness. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2764–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bervell, B.; Umar, I.N.; Kamilin, M.H. Towards a model for online learning satisfaction (MOLS): Re-considering non-linear relationships among personal innovativeness and modes of online interaction. Open Learn. J. Open Distance e-Learn. 2020, 35, 236–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M. Consumer trust, perceived security and privacy policy. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2006, 106, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkarainen, T.; Pikkarainen, K.; Karjaluoto, H.; Pahnila, S. Consumer acceptance of online banking: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Vonortas, N.S.; Han, S. Do-It-Yourself laboratories and attitude toward use: The effects of self-efficacy and the perception of security and privacy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 159, 120192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhi, M.; Hone, K.; Tarhini, A. A cross-cultural study of the intention to use mobile banking between Lebanese and British consumers: Extending UTAUT2 with security, privacy and trust. Technol. Soc. 2019, 59, 101151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kizgin, H. Examining the Influence of Mobile Store Features on User E-Satisfaction: Extending UTAUT2 with Personalization, Responsiveness, and Perceived Security and Privacy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, S.K.; Deb, N.; Roy, S. Investigation of Factors Influencing the Choice of Smartphone Banking in Bangladesh. Evergreen 2019, 6, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. Factors Impacting Behavioral Intention of Users to Adopt IoT in India. Int. J. Inf. Secur. Priv. 2020, 14, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information systems success: The quest for the dependent variable. Inf. Syst. Res. 1992, 3, 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success: A Ten-Year Update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorla, N. An assessment of information systems service quality using SERVQUAL+. ACM SIGMIS Database DATABASE Adv. Inf. Syst. 2011, 42, 46–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, N.N.D.; Dai Trang, T.T. Repurchase Intention: The Effect of Service Quality, System Quality, Information Quality, and Customer Satisfaction as Mediating Role: A PLS Approach of M-Commerce Ride Hailing Service in Vietnam. Mark. Brand. Res. 2018, 5, 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; He, J.; Shi, X.; Hong, Q.; Bao, J.; Xue, S. Technology Characteristics, Stakeholder Pressure, Social Influence, and Green Innovation: Empirical Evidence from Chinese Express Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensuse, D.I.; Rochman, H.N.; al Hakim, S.; Winarni, W. Knowledge management system design method with joint application design (JAD) adoption. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2021, 51, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggreni, N.M.M.; Ariyanto, D.; Suprasto, H.B.; Dwirandra, A.A.N.B. Successful adoption of the village’s financial system. Accounting 2020, 6, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albashrawi, M.A.; Turner, L.; Balasubramanian, S. Adoption of Mobile ERP in Educational Environment. Int. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2020, 16, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, T.; Ryu, S.; Han, I. The impact of Web quality and playfulness on user acceptance of online retailing. Inf. Manag. 2007, 44, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Leblanc, G. Corporate image and corporate reputation in customers’ retention decisions in services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2001, 8, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]