How Do Overseas Economic and Trade Cooperation Zones along the Belt and Road Affect the Economic Growth of Host Countries?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Literature Review of Overseas Economic and Trade Cooperation Zones

2.1.1. Foreign Studies on Cooperative Zones

2.1.2. China’s Research on Cooperative Zones

- A study on the overall construction, layout, and development of cooperative zones

- b.

- An empirical study on the economic benefits of cooperation zones

2.2. Studying Economic Growth Using the Double Difference Method

2.3. Summary of Literature Review

3. Research Hypothesis and Methodology

3.1. Research Hypothesis

3.2. Model and Variable Descriptions

3.2.1. Explained Variables

3.2.2. Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

4. Empirical Test

4.1. Baseline Regression

4.1.1. Baseline Regression Results

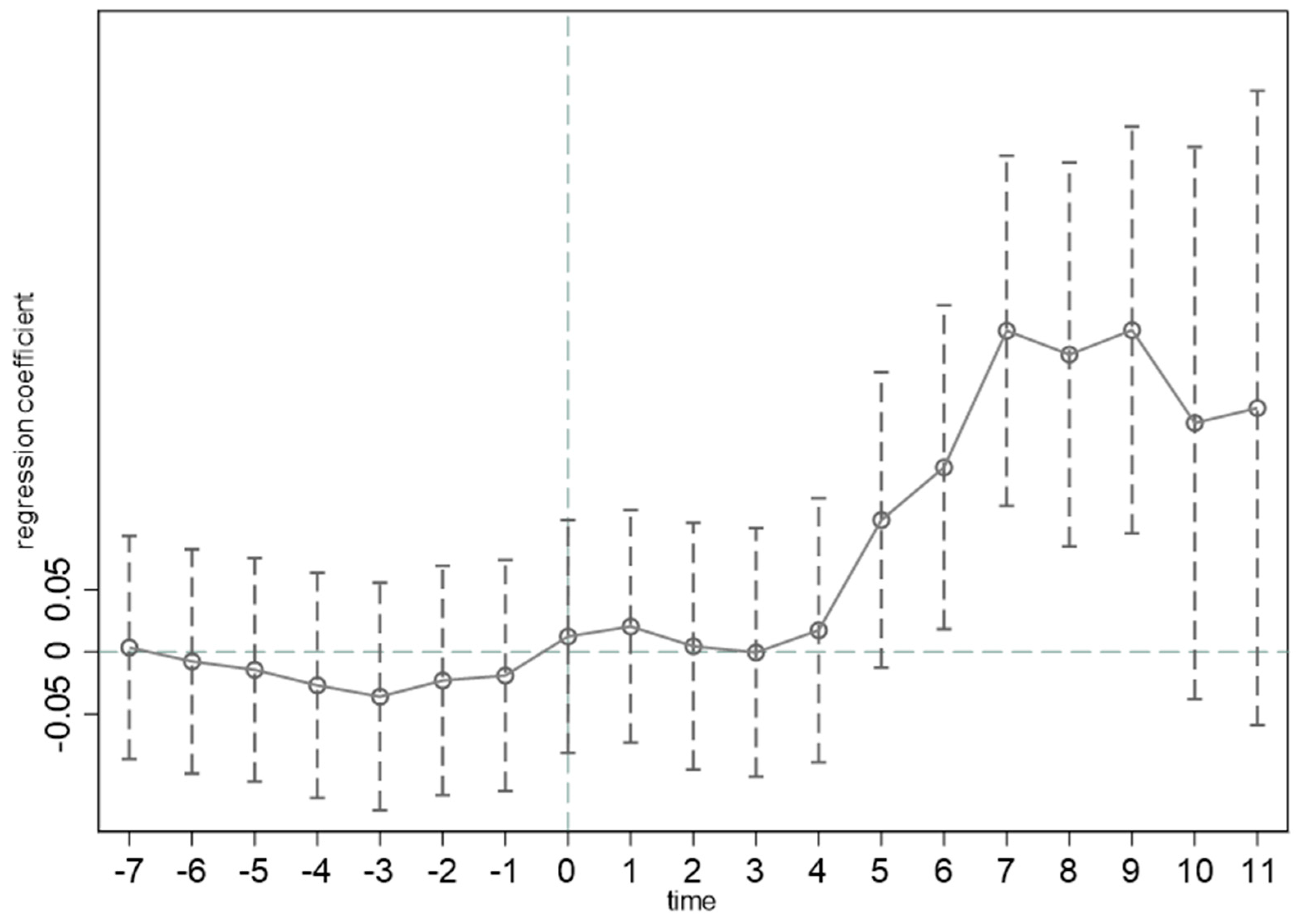

4.1.2. Parallel Trend Test

4.2. Robustness Tests

- Assuming that the cooperative zone is built before the actual year of construction

- b.

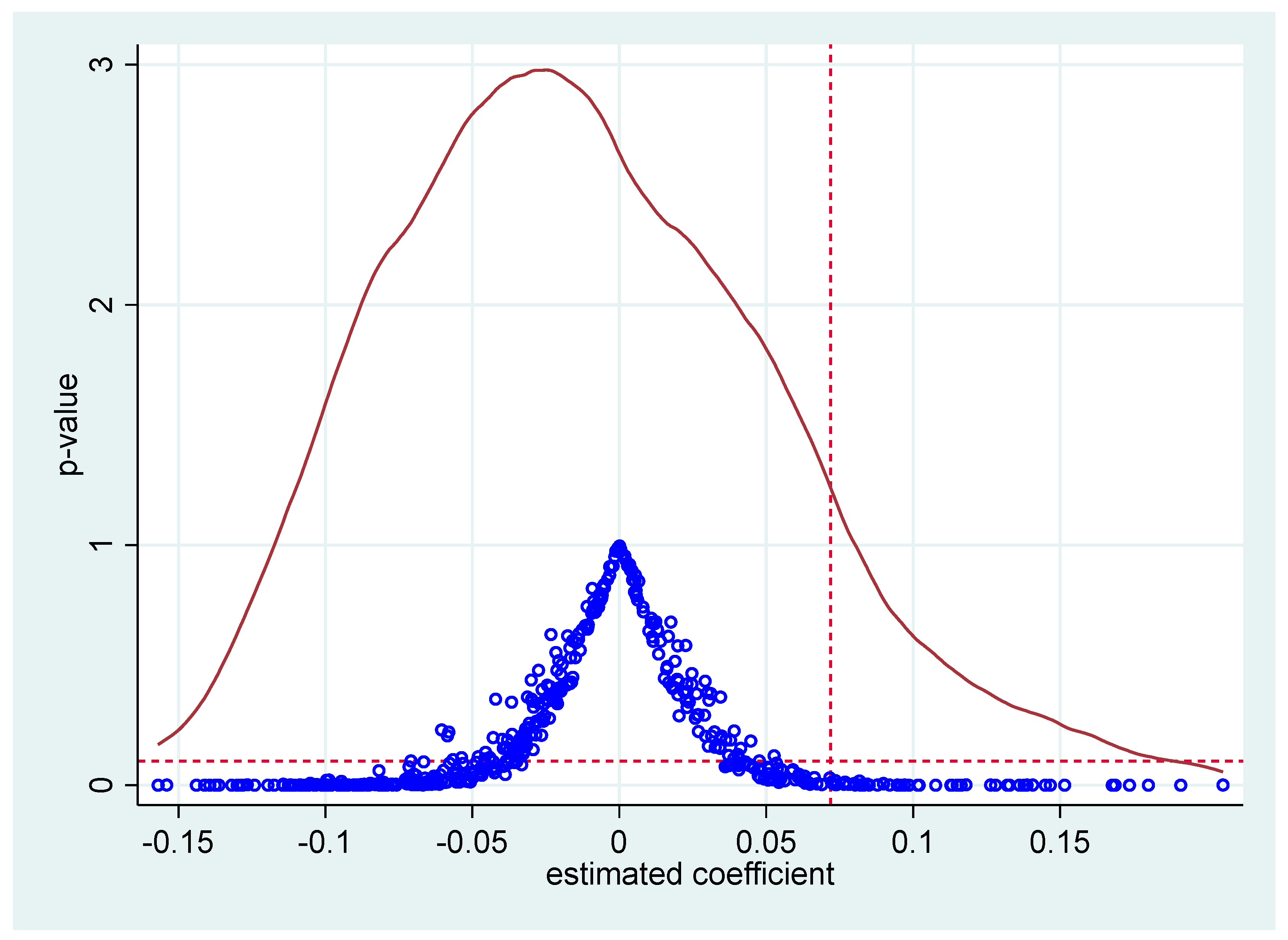

- Randomly generated pseudo-processing groups

- c.

- Substitution of core explanatory variables

- d.

- Changing the combination of variables and adjusting the sample time

4.3. Analysis of Influence Mechanisms

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. Based on the Different Economic Characteristics of the Host Country

4.4.2. Based on Different Types of Cooperation Zones

4.5. Conclusions of the Analysis

5. Further Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weijiang, F.; Zhizhong, Y.; Zhaoyi, F. The practice of China-Egypt Suez Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone. Int. Econ. Rev. 2012, 2, 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Jianan, L.; Long, S.N.; Zhang, S.W. A new way of China’s economic and trade cooperation—Overseas economic and trade cooperation zone. China Econ. Issues 2016, 6, 64–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Gozati, Y.; Wei, X.; Qidi, J. On the role of overseas parks in Chinese enterprises’ outward investment: The case of Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone in Cambodia. J. Geogr. 2020, 75, 1210–1222. [Google Scholar]

- Bräutigam, D.; Tang, X. “Going global in groups”: Structural transformation and China’s special economic zones overseas. World Dev. 2014, 63, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangwen, M.; Mingming, D.; Kushi, Z.; Jiguang, W.; Yang, Y.M.; Xiangxue, M.; Yue, Z.N. Investment benefits and inspiration of Long Jiang Industrial Park in Vietnam, an overseas park of China. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 39, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Shunqi, G. Construction of China’s overseas cooperation zones and host country economic development: The practice in Africa. Int. Econ. Rev. 2019, 3, 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, M.P.; Yeoh, C. Singapore’s overseas industrial parks. Reg. Stud. 2000, 34, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yejoo, K. Chinese-Led Special Economic Zones in Africa: Problems on the Road to Success; Centre for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch University: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. The economic impact of special economic zones: Evidence from Chinese municipalities. J. Dev. Econ. 2013, 101, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.Z. Global experiences of special economic zones with focus on China and Africa: Policy insights. J. Int. Commer. Econ. Policy 2016, 7, 1650018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiero, G.; Ogasavara, M.H.; Risso, M.L. Going global in groups: A relevant market entry strategy? Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2017, 27, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhengping, S.; Xiaobin, J.; Jie, Z. Study on the modes of Chinese overseas industrial cooperation zones along the Belt and Road. China City Plan. Rev. 2020, 29, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, Y.; Li, S.; Zhuang, L.; Zhu, X. A comparison and case analysis between domestic and overseas industrial parks of China since the Belt and Road Initiative. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1266–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Dunford, M.; Liu, W. Coupling national geo-political economic strategies and the Belt and Road Initiative: The China-Belarus Great Stone Industrial Park. Political Geogr. 2021, 84, 102296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.Y.; Zhang, Y. China’s overseas economic and trade cooperation zone construction and enterprises’ “going out” strategy. Int. Econ. Trade Explor. 2011, 27, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, L.; Hui, Z.; Junjie, H. The inspiration of Singapore’s overseas industrial park construction experience to China. Int. Trade 2012, 10, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M.; Zhang, C.Y. China’s overseas economic and trade cooperation zone: A platform for production capacity cooperation on “One Belt, One Road”. New Vis. 2016, 3, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Dawei, C.; Qian, F. Challenges and countermeasures for private enterprises to invest in the construction of “One Belt, One Road” overseas economic and trade cooperation zones. Econ. J. 2021, 7, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, X.; Jing, L. Global offshore industrial park models and development strategies of China’s new generation of offshore parks. Int. Econ. Rev. 2021, 1, 134–154. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.S. The logic and ideas of “Belt and Road” overseas economic and trade cooperation zone to empower the new development pattern. Reform 2022, 2, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhibin, F.; Wei, X.; Haiyang, L. Tax risk analysis of “going out” enterprises in China’s overseas economic and trade cooperation zones. Tax. Res. 2022, 8, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, B.; Qi, F.; Cheng, M. Research on the location choice of China’s overseas economic and trade cooperation zone—Based on the perspective of institutional risk preference. Int. Bus. J. Univ. Int. Bus. Econ. 2022, 2, 68–86. [Google Scholar]

- Congjun, T.; Bingqin, D.; Zhaoquan, J.; Zhiming, F.; Pinping, H. The dynamic renewal path of business models in overseas industrial parks in the context of “One Belt, One Road”: A case study of China-Indonesia Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone. World Econ. Res. 2021, 11, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Peiyuan, X.; Qian, W. Overseas economic and trade cooperation zones from the perspective of “One Belt, One Road”: Theoretical innovation and empirical test. Economist 2019, 11, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Li, J.Y. Research on the trade effect of overseas economic and trade cooperation zones along the Belt and Road and its realization path. J. Xinjiang Univ. Philos. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2020, 48, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Yuxuan, Z.; Yuan, Z. Research on the efficiency estimation and influencing factors of direct investment in offshore economic and trade cooperation zones. Yunnan Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, B.; Di, X.X.; Zhang, Y. Assessment of the trade effects of foreign economic and trade cooperation zones—Based on the host country perspective. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 7, 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Xiangwei, Z.; Xiaoning, L. Overseas economic and trade cooperation zones and foreign direct investment under the “Belt and Road” initiative. J. Shandong Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2022, 8, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Che, L.; Guo-Ming, X.; Jian, L. Analysis of bilateral economic and trade effects of offshore economic and trade cooperation zones—A test based on double difference method. Asia Pac. Econ. 2022, 3, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Xinye, Z.; Han, W.; Yizhuo, Z. Can “directly administered counties” promote economic growth?—A double-difference approach. Manag. World 2011, 8, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.M.; Zhao, R.J. Do national high-tech zones promote regional economic development?—A validation based on double difference method. Manag. World 2015, 8, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.; Xiang, X.R. Local financial institutions and regional economic growth—A quasi-natural experiment from the establishment of city commercial banks. Economics 2018, 17, 221–246. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.J. Can smart city pilot promote economic growth?—An empirical test based on double difference model. East China Econ. Manag. 2021, 35, 80–91. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Mediated effects analysis: Methods and model development. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D.; Anderson, J.; Bailey, N.; Alon, I. Policy, institutional fragility, and Chinese outward foreign direct investment: An empirical examination of the Belt and Road Initiative. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2020, 3, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.N.; Zhang, H. A study on the institutional environment and foreign direct performance of Chinese enterprises in host countries of the “Belt and Road”. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2020, 12, 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Jinye, L.; Xiaomin, S. Study on the impact of offshore parks on Chinese outward FDI—An analysis based on panel data of countries along the “Belt and Road”. East China Econ. Manag. 2019, 33, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Category | Variable Name | Variable Symbols | Variable Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variables | Gross domestic product per capita | The logarithm of the per capita gross domestic product | |

| Core explanatory variables | Foreign Economic and Trade Cooperation Zone | ||

| Intermediate variables | Foreign Investment Inflow | ||

| Control variables Other Variables | Total population | ||

| The natural resource output ratio | |||

| Business Freedom Index | |||

| Unemployment rate Number of cooperative area construction Gross Domestic Product Total workforce Investment Level Industrial development level Resident consumption level Trade Scale |

| Variables | Obs | Mean | Sd | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnPGDP | 1100 | 8.224345 | 1.367956 | 4.928473 | 11.35131 |

| lnFDI | 1108 | 19.94525 | 4.641675 | 0 | 24.51685 |

| lnPop | 1112 | 16.21053 | 1.563225 | 12.77535 | 21.01493 |

| Natural | 1100 | 8.864232 | 13.50604 | 0.0003131 | 86.45256 |

| Businessfreedom | 1112 | 63.84326 | 13.78653 | 20 | 100 |

| Uem | 1112 | 8.030353 | 6.171586 | 0.14 | 37.25 |

| Zones | 945 | 0.1936508 | 0.640744 | 0 | 8 |

| lnGDP | 625 | 24.98311 | 1.564371 | 21.16022 | 28.68712 |

| lnLabor | 640 | 15.39023 | 1.594473 | 12.04539 | 20.01858 |

| Investment | 589 | 26.34869 | 8.317225 | 10.21701 | 69.52741 |

| Industry | 620 | 31.17721 | 13.53498 | 8.058403 | 74.81215 |

| Consume | 435 | 22.82407 | 8.419502 | 3.690861 | 59.48478 |

| lnTrade | 959 | 24.28576 | 1.578006 | 20.54168 | 27.4178 |

| (1) lnPGDP | (2) lnPGDP | |

|---|---|---|

| Park | 0.0656 ** (0.2680) | 0.0620 ** (0.0247) |

| lnPop | −0.5760 *** (0.0545) | |

| Natural | −0.0005 (0.0013) | |

| Business freedom | 0.0034 *** (0.0009) | |

| Uem | −0.0200 *** (0.0033) | |

| Constant term | 7.4144 *** (0.0320) | 16.6324 *** (0.8875) |

| Country fixed effects | yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effects | yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1100 | 1100 |

| 0.1433 | 0.3269 |

| (1) lnPGDP | (2) lnPGDP | (3) lnPGDP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| −0.0273 (0.0289) | |||

| −0.3477 (0.0259) | |||

| −0.0318 (0.0258) | |||

| Control variables | yes | yes | Yes |

| Country fixed effects | yes | yes | Yes |

| Time fixed effects | yes | yes | Yes |

| Observations | 518 | 660 | 747 |

| 0.2451 | 0.2868 | 0.3179 |

| lnPGDP | |

|---|---|

| Zones | 0.0670 *** (0.0248) |

| Control variables | yes |

| Country fixed effects | yes |

| Time fixed effects | yes |

| Observations | 1100 |

| 0.3262 |

| lnGDP | |

|---|---|

| Park | 0.0577 * (0.0308) |

| Control variables | yes |

| Country fixed effects | yes |

| Time fixed effects | yes |

| Observations | 423 |

| 0.5735 |

| (1) lnPGDP | (2) lnPGDP | |

|---|---|---|

| lnFDI | 0.0044 *** (0.0017) | |

| Park | 0.0620 ** (0.0247) | |

| Control variables | yes | yes |

| Country fixed effects | yes | yes |

| Time fixed effects | yes | yes |

| Observations | 1098 | 956 |

| 0.3318 | 0.8249 |

| (1) lnPGDP | (2) lnFDI | (3) lnPGDP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Park | 0.0620 ** (0.0247) | 1.2602 *** (0.4509) | 0.0549 ** (0.0247) |

| lnFDI | 0.0041 ** (0.0017) | ||

| Control variables | yes | yes | yes |

| Country fixed effects | yes | yes | yes |

| Time fixed effects | yes | yes | yes |

| Observations | 1100 | 1098 | 1098 |

| 0.3269 | 0.0245 | 0.3296 |

| (1) lnPGDP | (2) lnPGDP | |

|---|---|---|

| Park | 0.6023 *** (0.1503) | 0.6173 *** (0.1766) |

| Park * Icomegroup | −0.2111 *** (0.0502) | |

| Park * Businessfreedom | −0.0088 *** (0.0028) | |

| Control variables | yes | yes |

| Country fixed effects | yes | yes |

| Time fixed effects | yes | yes |

| Observations | 1080 | 1100 |

| 0.3018 | 0.3333 |

| (1) Agricultural Cooperation Zone | (2) Industrial Cooperation Zone | (3) High-Tech Cooperation Zone | (4) Logistics Cooperation Zone | (5) Integrated Industrial Cooperation Zone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park | 0.1925 *** (0.0573) | 0.1985 *** (0.0691) | 0.1713 ** (0.0694) | −0.2143 (0.1335) | 0.0214 (0.0399) |

| Control variables | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Country fixed effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Time fixed effects | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Observations | 667 | 733 | 629 | 669 | 749 |

| 0.3163 | 0.4066 | 0.3415 | 0.2771 | 0.3264 |

| (1) lnTrade | (2) lnPGDP | |

|---|---|---|

| Park | 0.1239 * (0.0653) | |

| lnTrade | 0.5125 *** (0.0758) | |

| Control variables | yes | yes |

| Country fixed effects | yes | yes |

| Time fixed effects | yes | yes |

| Observations | 956 | 956 |

| 0.4214 | 0.8249 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Song, H.; Hou, C. How Do Overseas Economic and Trade Cooperation Zones along the Belt and Road Affect the Economic Growth of Host Countries? Sustainability 2023, 15, 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042894

Zhang H, Song H, Hou C. How Do Overseas Economic and Trade Cooperation Zones along the Belt and Road Affect the Economic Growth of Host Countries? Sustainability. 2023; 15(4):2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042894

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Henglong, Houlin Song, and Conglei Hou. 2023. "How Do Overseas Economic and Trade Cooperation Zones along the Belt and Road Affect the Economic Growth of Host Countries?" Sustainability 15, no. 4: 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042894

APA StyleZhang, H., Song, H., & Hou, C. (2023). How Do Overseas Economic and Trade Cooperation Zones along the Belt and Road Affect the Economic Growth of Host Countries? Sustainability, 15(4), 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042894