Abstract

Positive psychology and sustainable human development seek to improve the well-being of the individual. To achieve this well-being at the education level, positive education seeks to develop character strengths, and education for development facilitates the development of competencies. Moreover, the literature has demonstrated that the arts in positive education develop individual character strengths, socioemotional competencies and students’ relationship with their environment. Accordingly, in this systematic review, we aim to connect positive psychology and sustainable human development by evaluating the arts in education, based on the concepts of well-being. The results indicate that there are points of confluence between subjective and sustainable well-being, and illuminate the links and their connections between competencies and character strengths, with critical thinking functioning as an important connector between the two. Since character strengths are measurable and educable, we advocate their use as a tool to measure the human development index (HDI) in the education of a specific community. Thus, we are able to evaluate whether the competencies for development are achieved, as well as their role as determinants of the overall well-being of the individual. On the other hand, our work highlights the need to increase the number of investigations in this field to enable an empirical evaluation of how these connections are established and if they are efficient and durable.

1. Introduction

1.1. Positive Psychology and Sustainable Human Development as a Frame of Reference

Positive psychology, promoted by Seligman [1], presents a model of well-being. In positive psychology, research is carried out through the personal strengths that determine our patterns of behavior, emotions and thoughts, and our reactions to environmental situations. The strengths of character are summarized in six universal positive traits called “virtues”. As these virtues are very general and abstract, to measure them, they are defined by 24 strengths. For our study, this model of strengths is the most appropriate due to its global nature, excellent theoretical and empirical support and sufficient development in the educational world through positive education [2].

We present the virtues and strengths of character, according to Seligman and Peterson [2], in Table 1.

Table 1.

Virtues and strengths of character, according to Seligman and Peterson [2].

According to positive psychology, well-being and personal development are united processes. Seligman [3,4] states that, to achieve happiness or well-being, these personal strengths and abilities must be developed, thereby achieving balance and satisfaction in life.

Human development, on the other hand, entails growth that can also meet the needs of people, improving their capabilities as a means to achieve well-being. However, this human development must not only affect the person, but also what surrounds the person, i.e., his or her environment; that is, it places the person in a scenario where goods cease to be the center of attention, to be replaced by people [5].

1.2. Subjective Well-Being and Sustainable Well-Being: Confluences from Positive Education and Development

Seligman [3] (pp. 346–347) distinguishes three aspects of the concept of “happiness”: pleasure, commitment and meaning. People who believe they have a happier and fuller life are those who orient their lives towards these three aspects, especially the last two. Therefore, happiness is found in the balance between these three aspects [6,7,8,9].

Well-being is considered in positive psychology the equivalent to happiness, or “subjective well-being”, a state defined by each individual with two components: the emotional component (both positive and negative emotions) and the cognitive component, or thinking (if we do well in life, we feel happy) [10].

Psychological well-being provides benefits not only at the individual level but also at the social and community levels [11]. Therefore, happiness is an inner attitude not only of pleasure, meaning and personal commitment but also of relationships with others, conferring socioemotional properties as part of the strengths. This is the social objective of happiness. Thus, positive education that is born from positive psychology [12] is a model for the development of socioemotional competencies, feelings and strengths to achieve and improve well-being [13]. With positive education, the psychological plane is integrated with that of human development [12,14]. This shift towards human development is linked to the flourishing and growth of both individuals and their contexts and their achievement of happiness, highlighting the “care of oneself” (personal development) as a prerequisite to the care for others [15]. From this positive education, we deduce that human development is linked to eudaimonic happiness and personal and moral virtues [3,13].

According to education for development, well-being is defined as “personal fulfilment and development in all its dimensions (physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social) to a degree that enables a valuable and pleasant life”. Therefore, human development is a multidimensional process (economic, social, cultural, political and environmental), with an integrative, systemic and sustainable nature [16] (p. 33). On the other hand, in this pursuit of well-being, education for development is defined as “an educational process (formal, nonformal and informal) constantly directed, through knowledge, attitudes and values, to promote a global citizenship that generates a culture of solidarity, committed to the fight against poverty and exclusion, as well as the promotion of human and sustainable development” [17,18] (p. 13).

Such a broad definition requires more specificity than the broad concept of satisfaction of needs. Although the meaning of well-being is not exactly the same, we start from the basis that both positive psychology and sustainability share the same objective: seeking well-being [19,20]. Therefore, we believe that both disciplines can benefit from each other to produce a better definition of well-being [21].

The person and his or her environment are the two areas in which the individual carries out his or her human development. In their environment, defined as not only a personal environment but also a social environment, people thrive when they reach the highest levels of well-being [6,22]. Environmental sustainability offers various contributions to the definition of well-being by adopting a more systemic approach and incorporating points of view about society, time and the environment [19,21]. Thus, sustainable well-being occurs when individual and subjective well-being coincide with those of other individuals in an environment. This definition is compatible with that of positive psychology’s well-being [23]. The importance of the social environment and the inclusion of diversity emphasizes the positive value of the differences that Lopez-Cobo, Gómez-Hurtado, and Ainscow [24] have suggested promote human development. According to this systemic concept of human development, and by combining it with that of positive psychology, we arrive at a definition of sustainable and positive well-being where individual, social and environmental needs are interrelated.

1.3. Competencies and Strengths of Character as Tools for Positive Education and Sustainable Development

We find antecedents in the search for confluence between positive education and education for development in the objectives of the Muscat Agreement, the 2015 World Forum on Education and the working group for the post-2015 development agenda, continuing the objectives of the Millennium Development Goals (2000–2015), where all education was linked to sustainable development [25].

Positive education cultivates the fundamental strengths of character for each area of well-being in PERMA [2,4,26,27]. Every individual has main strengths that reflect who we are. The objective of positive education is, therefore, to promote well-being by helping students identify and apply their different strengths.

On the other hand, education for development, following the declaration of Aichi-Nagoya (2014), recognizes that education facilitates the acquisition of the “knowledge, skills, attitudes, competencies and values necessary to face related challenges to global citizenship and local, current and future contextual challenges” [28] (p. 2). This is how UNESCO itself defends itself, stating that one of the imperatives of education of the post-2015 agenda is “to improve the possibilities of acquiring knowledge and skills for sustainable development, global citizenship and the world of work” [29] (p. 4). It places training to foster the exercise of individual capacities at the top of its educational priorities [30]. Therefore, in the report “Teaching and learning. Towards a cognitive society” [31], the foundations of what will become lifelong learning and competencies are established [32].

The World Programme on Education for Sustainable Development, approved by the General Conference of UNESCO in 2014, indicates the fundamental competencies to be acquired by students of all ages: critical analysis, systemic reflection, collaborative decision-making and sense of responsibility for present and future generations [29] (p. 12).

Competency-based education facilitates a holistic approach that makes it possible to educate comprehensively [33], allowing the individual to take responsibility for his or her own learning, from being a consumer of knowledge to a creator of it [34]. For this approach, it is essential to train the skills that should be the objective of education [30]. Numerous studies have been carried out to identify and define the necessary competencies for sustainable development, among which those of [35,36,37,38,39,40,41] stand out.

The four competencies for sustainability prioritized by UNESCO and developed in [42] have specific components that Murga-Menoyo [30] has identified. Table 2 presents each of the components that this author has assigned to the different competencies.

Table 2.

Competencies for sustainability and its components, according to Murga-Menoyo [30].

1.4. Confluences of the Arts in Positive Education and Education for Development

The arts in education are linked to positive psychology and have been used to show that the study of the arts, such as music, empowers the fundamental strengths for the achievement of eudaimonic happiness and well-being [44,45]. Other studies that we use as a reference are [46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

This confluence of the emotional education in the arts with positive education contributes to the happiness of individuals and their personal and social well-being, developing the integral personality of students to face daily challenges and emotional intelligence when working with values [52], according to Álvarez Fernández [53] and Renom Plana [54].

The objectives of UNESCO concerning artistic education are collected in two documents, the “Roadmap” of the first World Conference of UNESCO for art education in 2006, and the Seoul Agenda, where an action plan was created [43,55]. The challenge is now to implement art education in a coherent way in the long term [56].

2. Methodology

According to what is expressed in the Theoretical Framework, which reflects the academic works published to date in this field, it is necessary to look for a relationship between the different constructs that will allow establishing the basis for future research and interventions in the educational and social field.

We intend, based on the literature, to connect positive psychology and sustainable human development. This connection will be carried out through the arts in positive education, using the concepts of well-being and development of both paradigms. Both positive psychology and sustainable human development formulate their own respective educational theories, which we connect through the strengths of character in positive education and competencies for sustainability.

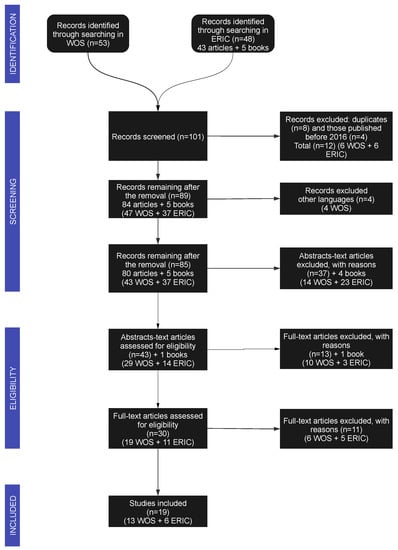

Hence, we carried out a systematic review of the literature using the umbrella of the PRISMA model [57] and the checklists of the CASP model [58] in the Web of Science (WOS) and Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) databases. We assigned each article an ID that begins with “W” or “E”, depending on whether it was found in the WOS (W) or ERIC (E) database.

2.1. Identification: Search Terms

To identify the search terms, we used the PICo criteria [59] for their reliability through keyword searches, based on the following PICo elements: participants, interventions and comparators.

- Participants: Children, youth and adult students engaged in primary, secondary or university education in formal, nonformal or informal education fields and in settings with low, medium or high social involvement.

- Intervention:

- Arts in education studies linked to character strengths.

- -

- Positive education studies related to the arts in education.

- -

- Studies of the relationship between the competence for sustainability and an operational breakdown of the character strengths of positive education in the context of the arts.

- Comparators: In terms of the search, we considered alternative interventions that contextualized the search within positive education and sustainable development in the arts.

To organize our search, we classified the terms into five constructs: Positive Psychology, Education, Arts, Skills, and Sustainable Human Development.

For each construct, we considered the following search terms: positive psychology (character strengths, values in action, positive psychology, eudaimonic happiness, happiness, well-being, eudaimonic well-being, and wellness), education (education, and positive education), arts (arts, arts-based education, education through arts, arts education, artistic education, arts in education, and arts-based programs), competences (skills, key competences, educational competences, emotional competences, social competences, cognitive competences, and basic skills), and sustainable human development (sustainable human development, and UNESCO).

By combining the nine terms related to positive psychology, the two terms related to education, the seven terms related to the construct of arts in the educational context, the seven search terms related to the key competencies and the two keywords related to sustainable human development, we performed a total of 1764 searches in each database (WOS and ERIC) using the Boolean operator AND.

These searches provided 53 articles in the WOS database and 48 references in ERIC, of which 43 were articles and 5 were books.

2.2. Screening

Before applying the exclusion and inclusion criteria, those articles that were duplicates (n = 8) or written before 2016 (n = 4) were eliminated using Microsoft Excel software. We decided to start the search for articles from 2016 because, on 1 January 2016, the world officially started implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Of the 101 initial references, 89 remained.

2.3. Eligibility

2.3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria

- Pragmatic criteria:

- ○

- Languages: English and Spanish.

- ○

- Studies of student population among children, youth and adults.

- ○

- Research of the articles carried out in a formal school environment (primary or secondary or equivalent in other countries), university, adult training or nonformal or informal environments.

- ○

- Publication date: Articles published after 1 January 2016 and until 2022.

- ○

- Publication type: Quantitative and qualitative articles and literature reviews. Papers, journal articles, indexed articles and book chapters, whether indexed or not in Scholarly Publishers Indicators (SPI).

- Quality criteria:

- ○

- CASP checklist: the ten questions of the CASP tool were answered, focusing on different methodological aspects, such as, whether the research methods were appropriate or whether the findings found by the authors were well presented and relevant.

- ○

- Reference databases: WOS, ERIC.

- ○

- Journals from quartiles 1 to 4 and nonindexed journals of authors of relevant prestige. Book articles and congress communications.

- ○

- The objectives of the studies of the selected articles are in line with the objectives of our research.

Exclusion criteria:

- Articles that do not reach the quality threshold.

- Duplicate articles.

- Population whose educational context is too informal and whose population is teaching staff.

- Research of the articles carried out with young children or a very young population.

- Articles published before 2016.

- Articles that are only indexed in reference databases, other than WOS and ERIC.

- Bachelor’s, Master’s and doctoral theses.

- The objectives of the studies of the selected articles are not in line with the objectives of our research.

2.3.2. Phases of the Review: Traceability

We applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria in four phases:

- Identification of articles in WOS and ERIC databases.

- Screening of articles. Studies in languages other than English or Spanish were excluded (n = 4). Of the 89 references, 85 were left: 43 in WOS and 37 in ERIC, of which 32 were articles and 5 books. We proceeded to read the abstracts. In this process, we screened the studies that were directly related to the constructs under study. Thus, 37 articles and 4 books were eliminated. The remaining references were subject to the next screening (29 from WOS and 14 from ERIC, of which 13 were articles and 1 was a book).

- Eligibility of articles. We proceeded to read the complete texts. To guarantee their eligibility, we applied the CASP checklist to not only each selected article but also the different stages of our review.

- In this last phase, 19 references provided conclusions that correspond to our research question: 13 from WOS and 6 from ERIC. We present a summary of the selected articles in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary table of selected articles.

Table 3. Summary table of selected articles.

Below, we present the scheme of the different stages of our literature review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature review.

3. Results

The results are presented in two sections below: the first section reflects the connections found between the main constructs of the study (subjective and sustainable well-being, positive and developmental education, positive psychology and sustainable human development), and the second section shows critical thinking as a connector of competences for sustainability and character strengths, and how these are connected in arts and education.

3.1. Linking the Main Constructs

3.1.1. Confluences of Subjective Well-Being and Sustainable Well-Being from Positive Education and Development

We have found results that corroborate the confluences of subjective and sustainable well-being through positive education and education for development, identifying an umbrella definition that fosters the production of well-being through the development of skills, competencies, strengths and capabilities of the individual in a social environment and is maintained over time.

For example, the 2012 Report on Human Development in Chile [79] (p. 128) defines capacities that affect both individual subjective well-being and subjective societal well-being [70]. According to this author, subjective well-being is the state of people who feel satisfied with their own lives and the conditions that society provides them to achieve their objectives. Therefore, it is society that offers, or does not offer, these capabilities and the possibility of developing them for individuals to achieve subjective well-being. Moreover, studies have been carried out that have determined the connection of well-being to positive psychology and sustainable development [80].

As Ronen and Kerret [72] have expressed, these studies have developed connections to well-being at different levels, such as psychological [81,82,83,84,85] and educational [86,87]. On this educational plane, the well-being sought by both positive education and development education is achieved in a reciprocal way. While society benefits from the subjective well-being that a person achieves due to positive education, this individual also benefits from the well-being that reaches his or her environment via the education for development [72]. This holistic and bidirectional sense of well-being has driven attempts to integrate the two approaches to education [20,87,88,89,90,91]. This concept of positive sustainability is the result of favoring sustainable well-being within a holistic view of well-being [72].

Notably, the holistic view of Nussbaum [92], which is cited by Frimberger [76] as appealing to the vision of Bildung, i.e., the educational development of students encompasses holistic objectives and competencies, entails the objectives of not only becoming an erudite and “competent” person but also becoming more human (moral and respectful) in the process.

3.1.2. Linking Competencies and Character Strengths in Positive Education and Sustainable Development

Our literature review has effectively reinforced the relationship between competences and strengths in human development, linking the environment to individual development. We can deduce this statement from studies such as that of Meriläinen and Piispanen [75], for whom competences are tools, and the mission of basic education is to equip learners with the necessary tools to cope openly with the various changes in the environment and the needs caused by them. The joint aim of these competences is to support growth as a human being and to function as a member of society while ensuring sustainable development, as well as to help learners to identify their own strengths and potential for development and to value themselves. For Farrington et al. [73], artistic and social-emotional competences are mutually reinforcing, and their development represent opportunities for change and evolution of these competences and foster well-being in young people. These interpersonal competencies help develop an integrated identity that will enable young people to interact productively with their environment, while being able to build and express a healthy sense of self and community.

3.1.3. The Arts in the Development of Character Strengths in Positive Education and Competencies in Development Education

Affirming the importance of the use of competencies and strengths for human development and well-being in education, our review highlights the importance of art in the improvement of both competencies and strengths.

In relation to the connection with the environment, with the arts in education, we can lay the foundations for the lifelong learning of students [70]. Additionally, Eveci [78] states that there is a complementarity between lifelong learning and art, e.g., writing. This lifelong learning generates the ability to react to environmental changes. For Johnston and Lane [60], the cognitive and creative skills associated with an artistic education reflect deep learning and an agile capacity for adaptation through synergy and symbiosis with personal or environmental change.

Such reaction to changes in the environment that promote lifelong learning is achieved via the development of the connection with others that facilitate the arts in education. Other authors, such as Garber et al. [67], in their theory of “making”, citing Gauntlett [93], state that artistic creation generates a connection with others. Similar to Gómez-Zapata et al. [69], citing Hille and Schupp [94] and Rentfrow and Gosling [95], we find that the arts help develop strengths, such as empathy. Rauduvaite and Yao [62] state that students who have worked in theatre develop competencies, such as environmental values, and strengths, such as empathy towards environmental problems. The feeling of inclusion was enhanced, as well as teamwork and cooperation, in the study of Andrikopoulou and Koutrouba [61]. Similarly, studies of Acai et al. [71] and Archbell et al. [74] cite different authors, e.g., Stueck et al. [96] and Ritblatt et al. [97], to suggest that participation in arts programs can increase social skills, which, citing Lobo and Winsler [98], could promote the development of social competence. Thus, Pledger [77] states that social interaction is one of the positive aspects of art.

The arts also help students to develop fundamental positive values and practices in their relation with their environment and their search for well-being. The article by Gómez-Zapata et al. [69] concludes that being involved in the arts helps develop various aspects of personality and allows participants to better judge both their own achievements and those of others. In the article by Rauduvaite and Yao [62], based on the research of Vasiliauskas [99], emotions are an important component in the structure of values. Likewise, Labor [65] indicates that exposure to arts programs has led to the formation of upright attitudes and positive practices [100,101,102]. In the article by Rauduvaite and Yao [62], students who have worked in theatre develop positive attitudes and a willingness to act and be part of an environmental change. Studies by Labor [65] have also revealed that participants in an arts program acquire knowledge, develop positive attitudes and communication skills and practice peacebuilding behaviors. In short, the objective of art-based methods is, like that of competency focused education, to strengthen self-knowledge and a positive self-concept and to analyze life, its phenomena, and the relationship of oneself with these [75].

3.2. Critical Thinking as a Connector of Competences for Sustainability and Character Strengths and How These Are Connected in Arts and Education

3.2.1. Critical Thinking as a Connection between Competencies for Sustainability and Strengths of Character

Another connection between competence for sustainability and strengths of character that is evident when analyzing the selected literature is found in critical thinking. Garber et al. [67] in their theory of “making”, develop the argument, citing Thwaits [103], that the arts in education provide us with the ability to analyze and find meaning in the environment. Labor [65] presents the conclusions reached by different authors, such as Duh [104], suggesting that art allows young students to acquire a better perception of the social world, influencing their knowledge of their daily life and their attitudes and beliefs about their participation in society [105]. Goldstein [64] states that it is very important to cultivate the emotional expressions of students and nurture their personal observations of the world, helping them critically evaluate the outside world. For Lan [68], artistic education helps children observe the nobility, goodness, sincerity and beauty of their surrounding world, including nature, art and interpersonal relationships, and to establish and create their own concept of beauty.

3.2.2. Connections in the Arts and Education between Strengths of Character and Competencies for Sustainability

This acquisition of competencies and strengths leads to making meaning and finding satisfaction in life. Garber et al. [67], citing Gauntlett [93], state that “making” generates joy and happiness and arises from the inner desire to give meaning or find satisfaction in life [106]. Positive relationships are an integral part of life satisfaction and the key factor in the well-being of happy people. Dance could be defined as a multidimensional and unique experience that contributes decisively to the integral development of the individual according to Sanderson [107], cited by Theocharidou et al. [66]. We could thus agree with the article by Clarke and Basilio [63], who propose a model in which the well-being of life satisfaction (hedonic) in school is affected by the commitment and joy of the performing arts through interpersonal well-being and competence (eudaimonic). Artistic experiences in school facilitate interpersonal connections, social integration (affinity) and empowerment (autonomy) [108]. Below is a table summarizing the different connections we have deduced from the literature in our Systematic Review (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of the connections found from the literature of our systematic review, and in which articles they occur.

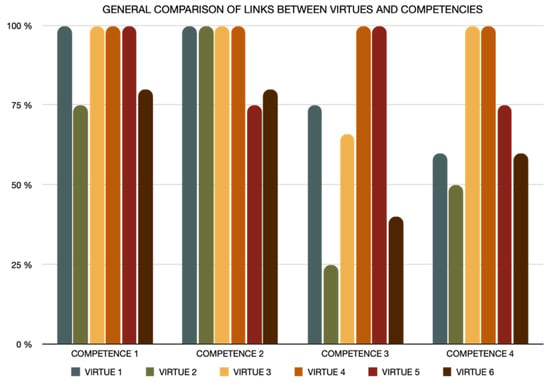

With the selected articles in our review, we have been able to trace relationships between the components of the competencies for sustainability and the strengths of character in a very implicit way (Table 5). This implicit link facilitates a holistic approach to well-being and a measurable and educable evaluation of education for development from positive psychology.

Table 5.

Strengths of character in relation to the components of competencies for sustainability.

Clearly, there is a set of character strengths that are related to most of the competencies for sustainability. However, the absence of a connection between strength 9 (vitality, enthusiasm, energy, passion) and 75% of competencies, such as 1 (critical analysis), 3 (collaborative decision-making) and 4 (sense of responsibility for present and future generations) is more remarkable. To a lesser extent, only 50% coincided with strength 20 (enjoyment of beauty and excellence), 21 (spirituality, purpose and faith) and 23 (humor and mischief), a proportion that does not seem to be linked to competencies 2 (reflection), systemic) and 3 (collaborative decision-making), in the case of strength 20, and for competencies 3 and 4, in the case of strengths 21 and 23. The character strengths that are linked to 100% of the competencies for sustainability are strengths 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 22.

In Figure 2, we visualize this comparison of the links of the competencies for sustainability with the virtues and, therefore, with the strengths of character.

Figure 2.

General comparison of the links between strengths of character and competencies for sustainability.

On this graph, we observe that virtue 4 (justice) is the only one that is 100% linked to all competencies and that virtues 2 (courage) and 6 (transcendence) are the least linked to the competencies for sustainability. Given that these links are confirmed, we suggest that strengths can be very useful for measuring the level of achievement of competencies and, therefore, well-being in sustainable development.

4. Discussion

Following the analysis of the articles that we included in our bibliographic review, we must emphasize that our main objective was to connect, through the literature, positive psychology and sustainable human development in positive education and the concepts of well-being and development from the arts; both paradigms rely on the existing link between competencies and character strengths.

Park and Peterson [109] specify the characteristics of the fortresses as follows:

- A set of individual positive traits that allow differentiating the strengths that people possess in different situations.

- These traits are manifested through actions, feelings and thoughts.

- They are modifiable throughout life.

- They can be measured.

- They are subject to contextual influences.

The United Nations Development Programme (PNUD) [110] has used various indicators, based on three of the essential components of well-being (long and healthy life, education and standard of living), to create the human development index (HDI) with which it evaluates human development, that is, the well-being of citizens [16]. As a result, various international initiatives, such as the “sustainable development goals” (SDGs), have been created.

At the educational level, extensive research has recently been carried out that supports the connection between the use of character strengths and various aspects of well-being [111,112,113,114,115], especially within the school environment [115,116,117,118]. Hence, given that the character strengths of positive psychology are measurable and educable and have been related to the competencies for sustainability, we believe that the sustainability framework can benefit from the use of strengths as a measurement tool in the evaluation of well-being. Similarly, positive psychology could benefit from the systemic thinking of sustainable development [20,21,23].

As the use of the strengths that each individual develops and are measurable have been associated with well-being [112,113,119,120,121], we can measure the combination of strengths that each individual possesses and that develops permanently and associate this with the achievement of competencies for sustainability. Therefore, we conclude that the use of character strengths in sustainable human development can be considered an optimal means for measuring the HDI.

Limitations and Recommendations

To the best of our knowledge, there is no other systematic review or study that relates the competencies for sustainability with the strengths of character at the level of the arts in positive education and for sustainable development. Therefore, we cannot compare our results to those of similar studies, nor can we know if our results are similar to those of other reviews. Hence, we believe that our research can provide an interesting field of study to codify or determine, in an explicit and concrete way, the strengths of character that are part of a given competency.

Furthermore, this analysis of the components of the competencies for sustainable development from the perspective of strengths of character can foster an important field of research in positive education concerning education for development and, via the field of sustainable human development, regarding the role of the strengths of character in positive psychology.

This initial connection between competencies for development and strengths of character in the field of arts in positive education that we have identified is a first step on the path to discerning more explicit links between the two. Future studies should therefore focus on educational projects in the arts that specify a model of education based on the overall student well-being.

Although limited to the context of positive education, our evidence shows that character strengths can be developed through education [115]. Accordingly, we need additional studies that bring together the five constructs (positive psychology, education, arts, competencies, and sustainable human development) to demonstrate our hypothesis in a more solid way.

Finally, it is also necessary for new studies to link the competencies of education for development with the strengths of positive education to create an adequate design that allows us to empirically evaluate this connection and affirm the strengths of character as an HDI to promote the global well-being of students.

5. Conclusions

As the results of our review show, we have been able to trace relationships between the components of the competencies for sustainability and the strengths of character in a very implicit way (Table 2 and Figure 2).

From these relationships, it is clear that the components of competencies for the sustainability of development education 1.1 (critical thinking), 2.1 (systemic thinking), 2.4 (feeling of belonging to the community) and 3.2 (participatory skills) coincide with at least half the character strengths of positive psychology. The development of these strengths is related to these competencies in the educational field. Therefore, we believe that the arts are the ideal vehicle to perfect these strengths and develop the competencies for sustainability to promote optimal human well-being and development.

Our results have demonstrated this connection, although we stress that the extant research typically defines and links the strengths of character and competencies in an implicit way through different terms. It is necessary, in the future, to develop a more explicit view of these constructs when studying and defining the relationship between them, especially between the construct strength of character and the competencies for sustainability. Only with this global vision can we reveal a totally explicit link and prevent possible interpretations of inter-construct relationships at the discretion of the reader.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.V.-M. and F.C.; methodology, P.V.-M. and I.L.-C.; software, P.V.-M.; validation, P.V.-M., F.C. and I.L.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.V.-M.; writing—review and editing, P.V.-M., F.C. and I.L.-C.; supervision, F.C. and I.L.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Seligman, M. The President’s Address. APA 1998 Annual Report. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 559–562. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C.; Seligman, M. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Classification and Handbook, 1st ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. La Auténtica Felicidad, 1st ed.; Vergara: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being, 1st ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, A. Desarrollo Humano. In Diccionario de Educación para el Desarrollo, 1st ed.; Celorio, G., López de Munain, A., Eds.; Universidad del País Vasco: Bilbao, Spain, 2007; pp. 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C.L.M.; Ryff, C.D. Subjective Change and Mental Health: A Self-Concept Theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oades, L.G.; Mossman, L. The Science of Wellbeing and Positive Psychology. In Wellbeing, Recovery and Mental Health; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Park, N.; Seligman, M. Orientations to Happiness and Life Satisfaction: The Full Life versus the Empty Life. J. Happiness Stud. 2005, 6, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.; Steen, T.A.; Park, N.; Peterson, C. Positive Psychology Progress: Empirical Validation of Interventions. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana Vañó, A. Psicología Positiva y Educación. Esbozo de una Educación desde y para la Felicidad. In Aplicaciones Educativas de la Psicología Positiva, 1st ed.; Caruana Vañó, A., Ed.; Generalitat Valenciana, Conselleria d’Educació: Valencia, Spain, 2010; pp. 16–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive Psychology. An Introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.; Ernst, R.; Gillham, J.; Reivich, K.; Linkins, M. Positive Education: Positive Psychology and Classroom Interventions. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2009, 35, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linley, A.P.; Joseph, S.; Harrington, S.; Wood, A.M. Positive Psychology: Past, Present, and (Possible) Future. J. Posit. Psychol. 2006, 1, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Pérez, C.; Pereira Domínguez, C. El Enfoque Positivo de La Educación: Aportaciones al Desarrollo Humano. Teoría De La Educación. Rev. Interuniv. 2011, 23, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerda, J.A. Bienestar. In Diccionario de Educación para el Desarrollo, 1st ed.; Celorio, G., López de Munain, A., Eds.; Universidad del País Vasco: Bilbao, Spain, 2007; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Carpio, M.L. Construyendo una ciudadanía global. Borrador para el balance 1996–2006. In Proceedings of the III Congreso de Educación para el Desarrollo, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 7–9 December 2006; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Carpio, M.L. Estrategia de Educación para el Desarrollo de la Cooperación Española, 1st ed.; Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación: Madrid, España, 2007; Available online: http://www.maec.es (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Helne, T.; Hirvilammi, T. Wellbeing and Sustainability: A Relational Approach. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C. Sustainable Happiness: How Happiness Studies Can Contribute to a More Sustainable Future. Can. Psychol. 2012, 49, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjell, O.N.E. Sustainable Well-Being: A Potential Synergy between Sustainability and Well-Being Research. Rev. Gen. Psychol 2011, 15, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L. Mental Health in Adolescence: Is America’s Youth Flourishing? Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2006, 76, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.L.; Williams, P.; Spong, C.; Colla, R.; Sharma, K.; Downie, A.; Taylor, J.A.; Sharp, S.; Siokou, C.; Oades, L.G. Systems Informed Positive Psychology. J. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 15, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Cobo, I.; Gómez-Hurtado, I.; Ainscow, M. The Real Happiness in Education: The Inclusive Curriculum. In The Routledge Handbook of Positive Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONU. Resolución 66/288 Asamblea General. 2012. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N11/476/13/PDF/N1147613.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Dahlsgaard, K.; Peterson, C.; Seligman, M. Shared Virtue: The Convergence of Valued Human Strengths across Culture and History. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2005, 9, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C. A Primer in Positive Psychology, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Declaración de Aichi-Nagoya Sobre La Educación Para El Desarrollo Sostenible; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Post 2015 Process: Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015 (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Murga-Menoyo, M.A. Competencias para el Desarrollo Sostenible: Las capacidades, actitudes y valores meta de la Educación en el Marco de la Agenda Global Post-2015. De Educ. 2015, 13, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión de las Comunidades Europeas. Libro Blanco Sobre La Educación y La Formación. Enseñar y Aprender—Hacia La Sociedad Cognitiva; Publications Office of the EU: Bruselas, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sabán Vera, C. La Educación Permanente y la Enseñanza por Competencias en la UNESCO y en la Unión Europea; Grupo Editorial Universitario: Granada, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gavotto Nogales, O.I. La Evaluación de Competencias Educativas: Una Aplicación de la Teoría Holística de la Docencia Para Evaluar Competencias, 1st ed.; Palibrio: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Delors, J.; Mufti, I. La Educación Encierra un Tesoro: Informe Para la UNESCO de la Comisión Internacional Sobre la Educación Para el Siglo XXI; Ediciones UNESCO: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Menoyo, M.A. Learning for a Sustainable Economy: Teaching of Green Competencies in the University. Sustainability 2014, 6, 2974–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar Minguet, P.; Ull Solís, M.A.; Martínez Agut, M.P.; Piñero Guillamany, A. Core Competencies for Sustainability: An Analysis from the Disciplinary Dialogue. Bordón 2014, 66, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, M.; Murga-Menoyo, M.A. The Processes of Integrating Sustainability in Higher Education Curricula: A Theoretical-Practical Experience Regarding Key Competences and Their Cross-Curricular Incorporation into Degree Courses. In Transformative Approaches to Sustainable Development at Universities; Filho, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Key Competencies for a Sustainable Development of the World Society: Results of a Delphi Study in Europe and Latin America. GAIA 2011, 20, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Future-Oriented Higher Education: Which Key Competencies Should Be Fostered through University Teaching and Learning? Futures 2012, 44, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key Competencies in Sustainability: A Reference Framework for Academic Program Development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.; Banas Mills, S. Moving Forward on Competence in Sustainability Research and Problem Solving. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2011, 53, 3–12. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1118768/Moving_forward_on_competence_in_sustainability_research_and_problem_solving (accessed on 25 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Morin, E. Los Siete Saberes Necesarios Para La Educación Del Futuro; Paidós, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014; Available online: www.unesco.org/open-ac- (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Hallam, S.; Cuadrado, F. Music Education and Happiness. In The Routledge Handbook of Positive Communication, 1st ed.; Muñiz-Velázquez, J.A., Pulido, C.M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, S. The Power of Music: Its Impact on the Intellectual, Social and Personal Development of Children and Young People. Int. J. Music Educ. 2010, 28, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clift, S.; Hancox, G.; Morrison, I.; Hess, B.; Kreutz, G.; Stewart, D. Choral Singing and Psychological Wellbeing: Quantitative and Qualitative Findings from English Choirs in a Cross-National Survey. J. Appl. Arts Health 2010, 1, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmberg, L.J.; Fung, C. Benefits of Music Participation for Senior Citizens: A Review of the Literature. Music Educ. Res. 2010, 4, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, R.A.R. Music, Health, and Well-Being: A Review. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2013, 8, 20635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, D.; Gaudreau, P. Music Listening and Emotional Well-Being in Adolescence: A Person- and Variable-Oriented Study. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 61, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickard, N.S.; McFerran, K. Lifelong Engagement with Music: Benefits for Mental Health and Well-Being; Rickard, N.S., McFerran, K., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarikallio, S. Music as Emotional Self-Regulation throughout Adulthood. Psychol. Music 2010, 39, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Marin, P.; Cuadrado, F.; Lopez-Cobo, I. Linking Character Strengths and Key Competencies in Education and the Arts: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Fernández, M. Diseño y Evaluación de Programas de Educación Emocional. Colección Educación Emocional y en Valores; Álvarez Fernández, M., Ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Renom Plana, A. Educación Emocional. Programa Para Educación Primaria (6–12 Años). Colección Educación Emocional y En Valores; Renom Plana, A., Ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2010—Seoul|United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2010. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/creativity/arts-education/world-conferences/2010-seoul/ (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Snook, B.H.; Buck, R. Policy and Practice within Arts Education: Rhetoric and Reality. Res. Danc. Educ. 2014, 15, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Guidelines and Guidance Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macaro, E.; Curle, S.; Pun, J.; An, J.; Dearden, J. A Systematic Review of English Medium Instruction in Higher Education. Lang. Teach. 2018, 51, 36–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathbone, J.; Albarqouni, L.; Bakhit, M.; Beller, E.; Byambasuren, O.; Hoffmann, T.; Scott, A.M.; Glasziou, P. Expediting Citation Screening Using PICo-Based Title-Only Screening for Identifying Studies in Scoping Searches and Rapid Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E.A.; Lane, J.F. Artist Stories of Studio Art Thinking over Lifetimes of Living and Working. Int. J. Educ. Arts 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulou, E.; Koutrouba, K. Improvised Eco-Theatre as Educational Tool for the Environmental Awareness of Elementary Students. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN17 Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 3–5 July 2018; pp. 2818–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauduvaite, A.; Yao, Z. Prospective Music Teacher Training: Factors Contributing to Creation of Positive State in the Process of Vocal Education. In Rural Environment Education. Personality (REEP). In Proceedings of the 13th International Scientific Conference, Jelgava, Latvia, 8–9 May 2020; pp. 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T.; Basilio, M. Do Arts Subjects Matter for Secondary School Students’ Wellbeing? The Role of Creative Engagement and Playfulness. Think. Ski. Creat. 2018, 29, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.H. The Greatest Benefit of Art Workshop: Well-Being. In Proceedings of the ERD 2018—Education, Reflection, Development, Sixth Edition, Cluj Napoca, Romania, 6–7 July 2018; 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labor, J.S. Role of Art Education in Peace Building Efforts among Out-of-School Youth Affected by Armed Conflict in Zamboanga City, Philippines. J. Int. Dev. 2018, 30, 1186–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharidou, O.; Lykesas, G.; Giossos, I.; Chatzopoulos, D.; Koutsouba, M. The Positive Effects of a Combined Program of Creative Dance and BrainDance on Health-Related Ouality of Life as Perceived by Primary School Students. Phys. Cult. Sport. Stud. Res. 2018, 79, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, E.; Beckles, K.; Lee, S.; Madan, A.; Meuschke, G.; Orr, H. Exploring the Relationship between Making and Teaching Art. Int. J. Educ. Through Art 2020, 16, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, F. The Role of Art Education in the Improvement of Employment Competitiveness of Deaf College Students. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2018, 284, 879–883. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Zapata, J.D.; Herrero-Prieto, L.C.; Rodríguez-Prado, B. Does Music Soothe the Soul? Evaluating the Impact of a Music Education Programme in Medellin, Colombia. J. Cult. Econ. 2021, 45, 63–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Durán, P. Una Educación Artística Para Desarrollar El Bienestar Subjetivo. La Experiencia Chilena. Rev. Int. De Educ. Para La Justicia Soc. 2017, 6, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acai, A.; McQueen, S.A.; McKinnon, V.; Sonnadara, R.R. Using Art for the Development of Teamwork and Communication Skills among Health Professionals: A Literature Review. Arts Health 2017, 9, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronen, T.; Kerret, D. Promoting Sustainable Wellbeing: Integrating Positive Psychology and Environmental Sustainability in Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, C.A.; Maurer, J.; Aska McBride, M.R.; Nagaoka, J.; Puller, J.S.; Shewfelt, S.; Weiss, E.M.; Wright, L. Arts Education and Social-Emotional Learning Outcomes among K-12 Students: Developing a Theory of Action; University of Chicago Consortium on School Research: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Archbell, K.A.; Coplan, R.J.; Nocita, G.; Rose-Krasnor, L. Participation in Structured Performing Arts Activities in Early to Middle Childhood: Psychological Engagement, Stress, and Links with Socioemotional Functioning. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2019, 65, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriläinen, M.; Piispanen, M. The Art-Based Methods in Developing Transversal Competence. International Electron. J. Elem. Educ. 2019, 12, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimberger, K. Towards a Well-Being Focussed Language Pedagogy: Enabling Arts-Based, Multilingual Learning Spaces for Young People with Refugee Backgrounds. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2016, 24, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pledger, C. Ballroom Dance: An Education Like No Other. Inq. J. Va. Community Coll. 2016, 20, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Deveci, T. Writing for and Because of Lifelong Learning. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2019, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güell, P.; Márquez, R.; Godoy, S.; Orchard, M.; Castillo, J. Desarrollo Humano en Chile 2012 Bienestar Subjetivo: El Desafío de Repensar El Desarrollo; González, P., Ed.; Sistema de Naciones Unidas en Chile: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dettori, A.; Floris, M. Sustainability, Well-Being, and Happiness: A Co-Word Analysis. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2019, 10, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral Verdugo, V. The Positive Psychology of Sustainability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2012, 14, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Mireles-Acosta, J.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Fraijo-Sing, B. Happiness as Correlate of Sustainable Behavior: A Study of Pro-Ecological, Frugal, Equitable and Altruistic Actions That Promote Subjective Wellbeing. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2011, 18, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Ortiz-Valdez, A. On the Relationship Between Character Strengths and Sustainable Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 877–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, I.J.; Raymond, C.M. Positive Psychology Perspectives on Social Values and Their Application to Intentionally Delivered Sustainability Interventions. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Fraijo-Sing, B.; Durón-Ramos, M.F. Assessing Sustainable Behavior and Its Correlates: A Measure of Pro-Ecological, Frugal, Altruistic and Equitable Actions. Sustainability 2013, 5, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerret, D.; Orkibi, H.; Ronen, T. Green Perspective for a Hopeful Future: Explaining Green Schools’ Contribution to Environmental Subjective Well-Being. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2014, 18, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C. Education for Sustainable Happiness and Well-Being. Education for Sustainable Happiness and Well-Being; Taylor and Francis Inc.: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ampuero, D.A.; Miranda, C.; Goyen, S. Positive Psychology in Education for Sustainable Development at a Primary-Education Institution. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P.; O’Brien, C.; Kay, B.; O’Rourke, K. Leading Educational Change in the 21st Century: Creating Living Schools through Shared Vision and Transformative Governance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerret, D.; Orkibi, H.; Ronen, T. Testing a Model Linking Environmental Hope and Self-Control with Students’ Positive Emotions and Environmental Behavior. Environ. Educ. 2016, 47, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C. Who Is Teaching Us About Sustainable Happiness and Well-Being? Health Cult. Soc. 2013, 5, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M.C. Cultivating Humanity; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauntlett, D. Making Is Connecting: The Social Power of Creativity, from Craft and Knitting to Digital Everything; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hille, A.; Schupp, J. How Learning a Musical Instrument Affects the Development of Skills. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2015, 44, 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentfrow, P.; Gosling, S. The Do Re Mi’s of Everyday Life: The Structure and Personality Corre-Lates of Music Preferences. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 1236–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stueck, M.; Villegas, A.; Lahn, F.; Bauer, K.; Tofts, P.; Sack, U. Biodanza for Kindergarten Children (TANZPRO-Biodanza): Reporting on Changes of Cortisol Levels and Emotion Recognition. Body Mov. Danc. Psychother. 2016, 11, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritblatt, S.; Longstreth, S.; Hokoda, A.; Cannon, B.; Weston, J. Can Music Enhance School-Readiness Socioemotional Skills? J. Res. Child. Educ. 2013, 27, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, Y.B.; Winsler, A. The Effects of a Creative Dance and Movement Program on the Social Competence of Head Start Preschoolers. Soc. Dev. 2006, 15, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliauskas, R. Theoretical and Practical Aspects of Value Education. Acta Paedagog. Vilnensia 2005, 14, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C. Engaging with the Arts to Promote Coexistence. In Imagine Coexistence: Restoring Humanity after Violent Ethnic Conflict; Chayes, D., Ed.; New Publisher: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, D. The Art of Building Peace: How the Visual Arts Aid Peace-Building Initiatives in Cyprus. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection, April 2006. Available online: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/370 (accessed on 27 September 2022).

- Shank, M.; Schirch, L. Strategic Arts-Based Peacebuilding. Peace Change 2008, 33, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaits, A. The Joy of Thinkering. In Makers, Crafters, Educators: Working for Cultural Change; Garber, E., Hochtritt, L., Sharma, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Duh, M. Arts Appreciation for Developing Communication Skills among Preschool Children. Cent. Educ. Policy Stud. J. 2016, 6, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omasta, M. Artist Intention and Audience Reception in Theatre for Young Audiences. Youth Theatre J. 2011, 25, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, 1st ed.; Harper&Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, P. Age and Gender Issues in Adolescent Attitudes to Dance. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2001, 7, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J. Childhood, Culture and Creativity: A Literature Review; Creativity, Culture and Education (CCE): Great North House, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Park, N.; Peterson, C. Character Strengths: Research and Practice. J. Coll. Character 2009, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PNUD. Informe Sobre Desarrollo Humano. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Gander, F.; Proyer, R.T.; Ruch, W.; Wyss, T. Strength-Based Positive Interventions: Further Evidence for Their Potential in Enhancing Well-Being and Alleviating Depression. J. Happiness Stud. 2013, 14, 1241–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, R.M. Character Strengths Interventions: A Field Guide for Practitioners. Character Strengths Interventions: A Field Guide for Practitioners; Hogrefe Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proyer, R.T.; Gander, F.; Wellenzohn, S.; Ruch, W. Strengths-Based Positive Psychology Interventions: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Online Trial on Long-Term Effects for a Signature Strengths- vs. a Lesser Strengths-Intervention. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, L.; Gander, F.; Proyer, R.T.; Ruch, W. Character Strengths and PERMA: Investigating the Relationships of Character Strengths with a Multidimensional Framework of Well-Being. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 15, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, L.; Loton, D. SEARCH: A Meta-Framework and Review of the Field of Positive Education. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2019, 4, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L. Good Character Is What We Look for in a Friend: Character Strengths Are Positively Related to Peer Acceptance and Friendship Quality in Early Adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 2019, 39, 864–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.; Holenstein, M.; Wepf, H.; Ruch, W. Character Strengths Are Related to Students’ Achievement, Flow Experiences, and Enjoyment in Teacher-Centered Learning, Individual, and Group Work Beyond Cognitive Ability. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.; Ruch, W. Good Character at School: Positive Classroom Behavior Mediates the Link between Character Strengths and School Achievement. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, P.; Singh, K. Do All Positive Psychology Exercises Work for Everyone? Replication of Seligman et al.’s (2005) Interventions among Adolescents. Psychol. Stud. 2019, 64, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linley, P.A.; Nielsen, K.M.; Wood, A.M.; Gillett, R.; Biswas-Diener, R. Using Signature Strengths in Pursuit of Goals: Effects on Goal Progress, Need Satisfaction, and Well-Being, and Implications for Coaching Psychologists. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 5, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, W.; Green, S.; Grant, A.M. A Pilot Study Evaluating Strengths-Based Coaching for Primary School Students: Enhancing Engagement and Hope. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 6, 71–83. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/5490367/A_pilot_study_evaluating_strengths-based_coaching_for_primary_school_students_Enhancing_engagement_and_hope (accessed on 15 November 2022). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).