1. Introduction

The change in socio-economic conditions and constraints associated with the pandemic have had a significant impact on the daily routine of individuals [

1]. Especially in the retail sector, it is necessary to understand current consumer behavior in a dynamically changing socio-economic environment where the social and economic security of the majority of the population is under threat [

2]. The present economic climate, marked by soaring inflation, diminishing or vanished employment prospects, an escalating energy crisis, and steep fuel prices, significantly affects consumers’ daily lives [

2,

3]. Therefore, it is necessary to address the key areas that determine consumers’ purchasing decision-making processes and the innovative factors influencing sustainability and retail development. Society must delve into the ‘black box’ of consumer behavior, employing empathetic understanding and thorough research to grasp the key attributes shaping consumers’ evolving lifestyles and preferences in relation to retail purchases [

4]. Connected to these shifts are transformations in the retail landscape, driven by innovative sales tactics, digital engagement incorporating artificial intelligence, and advanced e-commerce platforms. These changes are in response to the evolving patterns of shopping behavior and consumption [

5]. Understanding consumer behavior is a prerequisite for corporate success in retail, and can be examined on two levels [

6]. The first level is to explore which factors influence purchasing decision-making processes, to indicate patterns of consumer behavior and their responses to turbulent social change. The second level is to explore the retail industry’s readiness for dispositional buying behavior and to identify practical tools and practices that work in the modern retail industry, based on business process innovation, particularly in marketing communications. The COVID-19 pandemic has not only raised the problem of how to address the necessary physical isolation (by moving activities to the online environment) but, on a much larger scale, has emphasized sustainability and the preservation of the standard of living of society for the next generation [

7]. Consumers have changed; they have discovered the benefits of many activities in the online environment; they can do the shopping more conveniently from the comfort of their homes and save the time needed for shopping [

8]. They are more interested in spending time with families and friends; they are interested in their mental, physical, or artistic development; and they are interested in ethical shopping. The virtual world, in the form of various digital platforms, provides them with more shopping convenience, which makes consumers’ ethical approach to shopping even more important [

9]. All the issues identified represent challenges for the retail industry, which must respond to these changes with innovative practices that define the basis for sales success. The shift in socio-economic conditions, coupled with the challenges posed by the pandemic, has profoundly influenced consumers’ everyday lives [

9].

1.1. The Impact of the COVID 19 Pandemic on Purchasing Behaviour

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on the lives of people all over the world, and has significantly influenced their purchasing behavior. A new coronavirus disease spread rapidly worldwide, resulting in a global pandemic. The starting point can be traced back to 11 March 2020, the date when the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared COVID-19 a global pandemic [

10]. Lockdowns and world-wide restrictions have severely damaged the global economy. In the second quarter of 2020, GDP in the European Union (EU) fell by 11.9% [

11], and in the United States by 32.9% [

12], compared to the previous quarter. The anxiety and uncertainty accompanying the pandemic inevitably impacted life and consumer behavior. Preventive measures enacted by numerous countries restricted people’s movement, fostered uncertainty, and disrupted habitual consumer patterns and decision-making processes [

13]. During the first phase of the coronavirus lockdown, people experienced unexpected situations that led to a significant shift in consumer preferences. Goods were classified as essential and expendable, with only necessities available to shoppers during this period. There was no demand for lifestyle products, even without these restrictions. Like the swine flu epidemic, increased purchases of food, face masks, and disinfectants were noted during this period [

14]. A considerable proportion of consumers increased their food consumption, due to higher levels of anxiety [

15,

16,

17]. A study [

18] revealed that in ten European countries there was an increase in food consumption, attributed to the rise in remote-work arrangements. Research on this topic points to changes in consumer behavior due to stressful causes, where these behavioral changes aim to cope, at least partially, with intense pressure, and to alleviate existential difficulties [

19,

20,

21]. It is a person’s reaction to a stressful situation or condition of a more permanent nature that may affect his or her decision-making and behavior [

22]. Some studies have pointed out that fear may be the cause of irrational and non-standard purchasing behavior [

20,

23,

24]. Research into the immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on consumer consumption and purchasing behavior has confirmed several significant changes in purchasing patterns. During the pandemic, impulse buying in the form of pan-shopping [

25] was observed to a significant extent, leading to stockpiling of goods, including food [

26], cleaning and hygiene products, and medicines [

27]. Across all countries in the world, panic buying [

28], stockpiling, and consequently empty shelves in stores were quite common, even in developed countries [

29]. Therefore, panic buying as a social phenomenon has had an impact, especially in the retail sector [

30]. Panic arises because of stressful and upsetting events, where the goal is to regain a sense of balance and regulate the effects of stressful situations [

31]. Panic-buying behavior has gained attention as a social phenomenon, and is typically manifested during any pandemic when people feel a sudden need to stockpile for fear of future shortages or price increases [

32].

Psychology plays a major role in impulse panic-buying behavior. Some research considers psychological and situational factors to be critical [

33]. Psychological conditions significantly affect human cognition, decision-making, and behavior [

34]. Another research study [

35] found that the psychology of shopping in a crisis is driven primarily by recognizing material value and regulating negative emotions, through purchasing material goods. One of the most common psychological explanations is that hoarding storable items provides individuals with a sense of control over a high-risk situation resulting from a disaster [

36]. The onset and persistence of the COVID-19 pandemic left the public fearful and uncertain. Therefore, many consumers have turned to panic buying as a means to manage their feelings of insecurity and regain control of the situation [

29,

36,

37]. The perceived scarcity effect is also largely linked to this, and hoarding is intensified when there is a shortage of primary staples [

38,

39]. It also leads to individuals experiencing insecurity, which gradually triggers further efforts to frantically stockpile products. Survival psychology recognizes that individuals may undergo specific behavioral changes. Understanding consumers’ decision-making processes is essential when analyzing instances of individuals changing their behavior in response to health crises [

40,

41,

42].

To reduce the risk of infection, some people have purchased large volumes of goods with low-frequency of purchase [

43]. However, it is usually panic buying that causes situations to worsen when backstock is scarce, often leading to increased prices of food products [

36]. According to [

44], 64% of consumers have experienced product shortages in stores, and 50% of consumers have stocked up on products to avoid future shortages. In a survey conducted to study the stockpiling behavior of Danish and British shoppers in the early phase of a pandemic, it was found that only four of ten shoppers made no extra purchases [

45]. It was even found that consumers who panic shop for food because of COVID-19 could gradually acquire a long-term addiction in the form of compulsive buying behavior [

45]. In addition, prominent levels of improvisation, procrastination regarding leftover purchases, and an increased use of digital technology and home delivery, blurring the distinction between work and private life, and virtual meetings with friends and family, have been reported [

46,

47,

48,

49]. Unlimited or contactless shopping has gained new importance, due to strictly set standards of social distance. Changes have also been observed in the choice of shopping location, the type of goods purchased, and the acceptance of digital payments. People reacted both psychologically and behaviorally to the ubiquitous news about the severity of the disease throughout the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the information presented in the form of multiple messages through mainstream media and social networks [

27,

28]. News of lockdowns, border closures, and problems with retail supply and stock-outs of certain products led to significant uncertainty, and induced fear in people [

50,

51,

52]. Everybody perceived future uncertainty [

36], particularly concerning food security [

53,

54]. The phenomenon of COVID-19 caused anxiety among consumers, largely because of the many uncertainties associated with the disease and its consequences [

55]. This situation also affected those consumers who had no schooling for coping with panic anxiety and disorders.

Thus, government information management and transparent communication will be crucial during any future pandemic or crisis. At the same time, it is the responsibility of retailers to quickly inform consumers of product availability, and this will also play a leading role in protecting them from the risk of panic buying [

13].

1.2. Sustainable Consumption and Changes Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

In recent years, sustainability has become an increasingly major decision factor regarding most consumer goods. The impact of sustainable consumption is reflected in the economy, society, and the environment [

56,

57]. Responsible (sustainable) consumption is defined as consumers’ efforts to reduce environmental impacts. It assumes that consumers tend to have a deeper perception and interest in moderation in consumption [

58]. In this context, sustainability includes caring for the environment, for quality of life, and for future generations [

59]. In addition, consumers’ shift towards more sustainable behaviors can significantly reduce their carbon impact, contributing to sustainable development [

60]. A study on global sustainability found that 73% of consumers declare their willingness to change their purchasing decisions and consumption habits, to reduce their environmental impact [

61]. Therefore, it is important for local authorities, including retailers, to address whether and how they could potentially intervene in consumption patterns in order to influence consumer behavior and their quality of life, and to improve the quality of life and the impact of their consumption behavior not only on themselves, but also on other consumers, the community, society, and the environment [

62]. More communication and a greater media presence are factors that can positively influence the acceptance of any new and important idea [

63].

During the pandemic, consumers have become aware of the importance of hygienic products, environmentally friendly products, and regional (local) products [

49]. Consumers have started buying more organic food and food directly from their producers—farmers [

64]. Some studies show the positive impact of the pandemic on more-sustainable purchasing behavior. Globally, Nielsen conducted research [

65] on consumer attitudes and behaviors during pandemics, and found that, in March 2021, there was a 33% increase in sales of certified organic food, compared to the same period a year before. Similarly, there was a 71% and 41% increase in sales of lactose-free milk and ROS gluten-free beverage products, respectively, which may indicate a growing concern for one’s health. The pandemic has highlighted the need to switch to more-sustainable food production methods and ways of consuming food. Therefore, analyses that address changes in consumer purchasing behavior in the context of COVID-19 in relation to sustainability are particularly important [

27]. Many studies address consumers’ attitudes, purchasing patterns, and consumption behavior when purchasing products with sustainable characteristics (e.g., organic food, animal-welfare food, fair-trade food, environmentally friendly food, local food, etc.), prior to the COVID-19 pandemic [

66,

67,

68]. Until now, few studies have examined how COVID-19 has affected Czech consumers and their attitudes towards purchasing sustainable products. This research encompasses more complex post-truth determinants of Czech consumers’ rates of making sustainable purchases in general, as well as their consumption. In this context, the main objective of this study is to analyze trends in consumer preferences for sustainable behavior before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.3. Innovation in Retail and Consumer Behavior

Progress in retail is based on two main pillars: innovation and sustainability. There is empirical evidence that both innovation and sustainability contribute to customer satisfaction. The path to achieving satisfaction in retail requires the promotion of both innovative (product, marketing, and relationship innovation) and sustainable (environmental, social and economic) practices [

69]. With the development of behavioral economics, the theory of social preferences is often used. These social preferences are distinct from economic motivation, and influence the behavior of all actors along the supply chain [

70].

Before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the annual growth in retail turnover was steady, at an average of 2–3%. As a result of the pandemic, the world economy contracted by 1.5–4.0% in 2020, marking the worst economic recession since the 1930s [

71]. The pandemic has changed not only global economic outcomes. but also the entire retail competitive landscape [

72]. Small retail stores are among the first to suffer significant financial losses in an economic downturn, something that happens usually every time [

73]. Therefore, innovation in the context of sustainability can play a significant role in supporting retail businesses. Another typical feature of consumer behavior in the presence of any health risk caused by the spread of a disease affecting health is the reduction in physical store visits and a shift in interest towards electronic forms of shopping. Consumers reduced their spending on food in stores and away from home, while increasing their spending on food purchased online, suggesting that changes in shopping location influenced changes in consumer food consumption and post-food expenditures [

74]. A study [

18] showed that 45% of consumers in 10 European countries shopped for food online more during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consumers tended to shop online more than in supermarkets, to reduce the potential risk of infection. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced another problem that has hit consumer behavior hard. In addition to the physical isolation that has caused a change in consumer behavior and the need to shop online, it has also highlighted the importance of the topic of health and its value, to a much greater extent. The notions of sustainability and conservation have become more prominent. It was a big challenge for the retail industry not to lose consumers and to remain viable during a pandemic crisis. Retail focused on the following aspects, which formed the backbone of the change in consumer behavior:

These aspects are part of a partial ethical and sustainable approach to shopping. The heightened interest in producing and processing raw materials, along with advancements in production technologies, has played a pivotal role in supporting consumer health. Sustainability of values can be characterized by consumer concern for the quality of the goods purchased and the stability of retail sales. Consumer lifestyles have become more intertwined with responsibility in purchasing decisions, and the online world of retail has created a new parallel of shopping that has offered consumers a contactless form of commerce. User-generated content is increasingly important in all fields and sectors [

75]. All these aspects contributed to considerable shopping convenience. The retail response had to take the initiative and accommodate these aspects. In a pandemic crisis, retailers who did not understand the situation did not stand up to the competition. Retail activity gradually developed into innovation, which positively influenced consumer purchasing decisions. In the case of food, the retail industry transformed itself into an importing service, as it found that consumers became more trusting of food imports, which contributed to their convenience shopping. It was convenience shopping that saw significant weight attached to the introduction of innovations that pushed the retailer’s opportunities for attracting consumers toward innovative forms of communication.

1.4. Ethical and Innovative Approach to Food Waste

Consumer attitudes towards food waste played a significant role in relation to the ethical approach to food purchasing. During the pandemic period, consumers’ interest in minimizing food waste was clear. Reducing food waste is a significant issue affecting the environment, the economy, and society. Food waste occurs throughout vertical food-processing and marketing, and consumers play a significant role. The modern food retail industry strives to significantly reduce food waste, which generates toxic gases and poses a severe risk to human health and the environment [

76]. In addition, food waste leads to the loss of scarce land, water, and energy resources [

77] In their study, Principato et al. [

78] formulated various aspects of the food waste phenomenon at the consumer level, which includes high consumer-consumption behavior. One of the principal factors in the innovation of this process to mitigate food waste is the prevention and implementation of the 3R (reduce, reuse, recycle) principle [

79]. The 3R principle is one of the ways to reduce resource consumption, food consumption, and food residue management across the entire production, processing, and marketing vertical. Food reduction affects the entire food supply chain, from agriculture to food service [

80]. The pandemic crisis prompted a notable shift in attitudes towards food shopping. This change was manifested not only in a move towards online shopping, but also in a more thoughtful approach by consumers regarding their purchases, with them aiming to minimize post-consumption food waste. Food waste can be significantly reduced through simple steps such as meal planning, creating shopping lists, using leftovers, and storing food properly [

81] According to professional estimates, one third of the food produced globally for human consumption is wasted [

82,

83]. Thus, organizations and governments can strengthen individual consumer responsibility by increasing awareness of waste prevention behavior, leading to increased accountability for food waste. Programs can be developed to reduce food waste and its environmental impacts. Through these activities, people can learn about the impacts of food waste and be inspired to prevent it. Therefore, consumers’ concern for the environment can increase, consequently influencing their attitudes toward food waste. Techniques supporting the subjective norm and attitude that food waste is unacceptable should be developed. Attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and waste prevention are the principal factors that can directly influence food-waste reduction. These factors should be the focus of interventions and policies aimed at reducing food waste. For example, campaigns and education programs aimed at changing individuals’ attitudes towards food waste could effectively promote behaviors that reduce waste. In addition, programs aimed at increasing perceived control of individual behavior, such as providing information on food waste, could also be effective. From the retail side of sustainability and business viability comes one form of innovative solutions leading to a more efficient use of resources to reduce food waste. This is a form of business called bricolage (EB). Entrepreneurial bricolage (EB) has become part of modern management in retail as well, contributing to the creation of sustainable competitive advantage in retail and consumer firms, influencing the benefits of differentiation and risk management, and co-creating service innovation in resource-constrained environments [

18] Entrepreneurial bricolage works with change processes that are welcomed by consumers in retail. At the same time, post-food waste can be controlled and prevented.

1.5. Innovation and Consumer Behavior

In the days before the pandemic, consumers’ main goal was to maximize comfort, which meant the desire to use any service or to purchase any product at any time. Consumers’ priority was the speed of delivery of products and services, including their availability. The pandemic introduced many obstacles that severely limited consumer convenience. Purchasing behavior was no longer as spontaneous as before; every visit to the mall had to be carefully planned. Therefore, during the COVID-19 constraints, many retail companies moved their business activities online, and started using innovative sales elements in their offer. Innovative technologies that use shared communication between consumers and retailers have emerged as one of the effective innovative elements. These are intelligent cloud-based applications, such as ERP and CRM. Currently, these platforms work with artificial intelligence that can develop a prominent level of accuracy with predictive analytics. The retail communication process will typically see the consumer interacting with an increasing number of deployed robots, virtual assistants, and virtual reality. The consumer will be more involved, and will actively participate in the process. Other innovative elements will be digital communication in the form of unique and individual offers tailored to the consumer’s personality. The prerequisite for this innovation is knowledge of the consumer’s characteristics, which will be communicated to the retailer via a virtual/digital platform. Innovation is usually based on an idea that breaks away from conventional/standard phenomena. In digital marketing communication, the retailer’s communication with the consumer becomes a dialogue, where the priority is the consensus of both areas of opinion, based on information sharing. As a result, the market offerings have become more personalized, fully catering to consumer satisfaction. Take sub-selling as an example, where innovation hinges on four key pillars of successful sales strategies:

- (1)

The ability to attract attention.

- (2)

The ability to convey an essential message.

- (3)

The ability to persuade.

- (4)

The ability to initiate a purchasing decision.

The core objective of these sales promotions and communication strategies is to engage consumers actively in the sales process. Nowadays, consumers can tailor their purchases precisely to their needs, using modern media and applications. From a retail standpoint, this mode of communication stands as one of the most rapidly expanding platforms. Innovations in this area are anticipated to be key drivers of meeting social needs sustainably and enhancing the competitiveness of retail businesses, ultimately determining their success. Currently, these tools are predominantly utilized in the online environment, encompassing various formats, such as podcasts, video conferences (Zoom, Google Meet, Hangouts, Skype, Webex, Whereby, Jitsi), group communication platforms (Slack, Discord, Google Chat, Microsoft Teams, Google Groups), shared information resources (Google Docs, Sheets, Keep), and communication applications (WhatsApp, Viber, Facebook Messenger).

As a result, there is a need to understand new consumer behavior regarding new theories, marketing strategies in the post-COVID-19 situation, and factors influencing consumers when purchasing goods or services after the market is closed. It turned out that there needs to be more empirical data on sustainability and changes in purchasing behavior, comparing the situation before and after the pandemic in the Czech Republic [

83]. Therefore, the research focused on the differences in consumer purchases of sustainable products by consumers, comparing the situation before the COVID-19 pandemic and after the pandemic subsided. The aim of this research was to investigate the degree of willingness to purchase sustainable products after an exceptional experience in life, in conditions of significant restrictions in many areas of everyday life during the pandemic, and at the same time, to point to consumers as the driving force behind innovation in retail. Our research builds on the previous research conducted in this area, and tries to solve the identified gap in the existing knowledge.

Consumer Behavior Patterns in Food Purchasing

Understanding consumer behavior in food purchasing necessitates an exploration of the distinct approaches adopted by men and women. According to [

84], male consumers can be categorized into four distinct groups:

Busy customers—they are men in managerial positions with high incomes. Their grocery shopping is fast; they are not influenced by price and discount events. They do not want to waste time shopping. They are aged between 28 and 36 years old.

Fair customers—they are men with low income, but higher education level. They often live alone, buy food with pleasure, and consider shopping as a social process. They are between 25 and 30 years old. They plan their purchases; they are not influenced much by flyer offers.

Apathetic customers—highly educated men with the highest incomes, showing reluctance to buy food and ignoring marketing promotions for food sales.

Economy customers—men with low incomes and lower education level. They are very sensitive to price changes and price relationships. They welcome price benefits and regularly follow marketing events.

According to [

84], women are divided into three groups:

Fair customers—women who consider grocery shopping necessary; these women are young, with a higher level of education.

Apathetic customers—women with high incomes aged between 28 and 32. Food shopping is neutral; they do not enjoy it. They shop slowly, and think about what food to buy for a long time.

Economic customers—women affected by the household budget. They buy food at lower prices and consider food alternatives. They like shopping. They are women of and older age and lower education level.

Generally, men share more responsibility for buying food; they want to support their partners and thus control household expenses, becoming more sustainable. On the other hand, women primarily enjoy shopping for food more than men; sustainability is more important here than expected.

According to the purchased food and the sustainability, customers can be divided into five groups [

85]:

- (1)

Customers preferring fresh food.

- (2)

Customers preferring a healthy lifestyle.

- (3)

Customers who enjoy grocery shopping.

- (4)

Customers in a hurry.

- (5)

Customers focusing on sweets.

Knowing the types of consumers buying food is essential for investigating their sustainability, i.e., their approach to ethical shopping.

2. Materials and Methods

The data were obtained in 2021 from research conducted by the Department of Business and Finance of the Faculty of Economics and Management of the Czech University of Life Sciences in Prague. One thousand one hundred and ten respondents voluntarily answered the questionnaire, with the following characteristics: (aged 15–93; 60.00% women; 38.3% with a university education; 37.4% families with children; N = 1110). Respondents were assured that the results would be presented in anonymized statistical form, and that the data would not be passed on to a third party. The snowball method was used to select the sample. The snowball technique in data collection assumes that respondents who have already filled out the questionnaire will suggest other respondents who could also fill out the questionnaire. The research results from 2021 were compared with the research in the same topic conducted within the Department of Business and Finance in 2018. One thousand and six respondents (aged 17–91; 54.2% women; 30.8% with a university education; 42.5% of families with children; N = 1006) participated in this research. We have identified the changes in customers’ purchasing behavior concerning purchasing ethical products, in a comparison between the period before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The data used in the research were collected using an online questionnaire through Google Forms. According to [

86], Internet surveys give researchers access to a unique population, and offer the possibility of collecting data in a shorter period. The questionnaire consisted of three sections: the first section contained questions regarding the demographic profile of the respondent (the demographic profiles of the respondents are shown in

Table 1); the second section related to the intensity and reasons for making purchases of products that can be described as ethical before and after the COVID-19 situation; the third section contained questions regarding the approach to waste management and ways to minimize it. This part of the questionnaire was not the subject of this article. The questionnaire contained a combination of closed questions, with the option of choosing a multi-item measurement of four constructs on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Respecting Ajzen’s recommendations [

87], all items that measured intentions and perceived behavioral control were formulated in relation to the specific context in which the behavior was manifested.

The odds ratio (OR) was used to analyze the frequency of occurrence of a specific behavior of the respondents. Specifically, the level of resistance to selected types of behavior or, conversely, the tendency towards them (e.g., a certain degree of buying “responsible” products, reading, or, on the contrary, ignoring product labels, and boycotting unethical products) was among between different groups of respondents (between men and women, between groups of respondents with a different economic status or a different education level, and between childless respondents and those who had children).

The odds ratio [

88] assesses a chance to resist. It is calculated as follows:

If OR = 1, there is no dependency between the observed variables. OR > 1 means that affiliation with the second group is a risk factor (members of the second group more often behave in the observed manner), and vice versa; OR < 1 means that the affiliation with the second group is a protective factor (members of the second group behave in the observed manner less often).

Strictly speaking, our goal was to use the OR application to focus on cases where there were different types of behavior between individual groups of respondents, and on whether and how these differences have changed during the pandemic, using a comparison of survey results from 2018 and 2021.

The survey results were presented by relative frequencies of responses to selected questions, and visualized using graphs of interactions between frequencies. Pearson’s

χ2-test (chi-squared) test was used to verify Czech consumers’ willingness to purchase sustainable products, and their opinions and attitudes.

The following hypotheses were tested:

H1. The frequency of purchasing ethical products depends on the presence of children in a family.

H2. The change in perception of ethical products during COVID-19 depends on the presence of children in a family.

H3. The frequency of purchasing ethical products depends on the income per family member.

H4. The change in perception of ethical products during COVID-19 depends on the income per family member.

Assuming that the data are ordinal and the number of observations is large, we can run a t-test. For the test of statistical hypotheses and the following analysis, the significance level α = 0.05 was used. We employed a one-factor ANOVA test to examine the relationship between income groups and shifts in attitude and to compare the mean frequencies of ethical-product purchases. Additionally, LSD post hoc tests were utilized to analyze the differences between pairs of these groups. These analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software, version 24.

3. Results

The following analysis aims to determine whether, and to what extent, the attributes of ethical shopping differ among different groups of respondents (e.g., between gender, economic status, education, and the presence of children in the family). Based on the respondents’ answers, the intensity of the preference for ethical aspects when purchasing was evaluated by the intention to read additional information on product packaging and the degree of boycott of products that did not meet ethical principles. For all these phenomena, the attributive risk and the odds ratio were calculated within individual pairs of respondent groups:

Male and female respondents.

Respondents who described their economic situation as very bad and rather bad.

Respondents who described their economic situation as rather bad and rather good.

Respondents who described their economic situation as rather good and very good.

Respondents with completed primary and secondary education.

Respondents with secondary school and university education.

Respondents with children and those living without children.

3.1. Comparison of the Impact of Ethical Shopping Attributes on Different Groups of Respondents in 2018 and in 2021

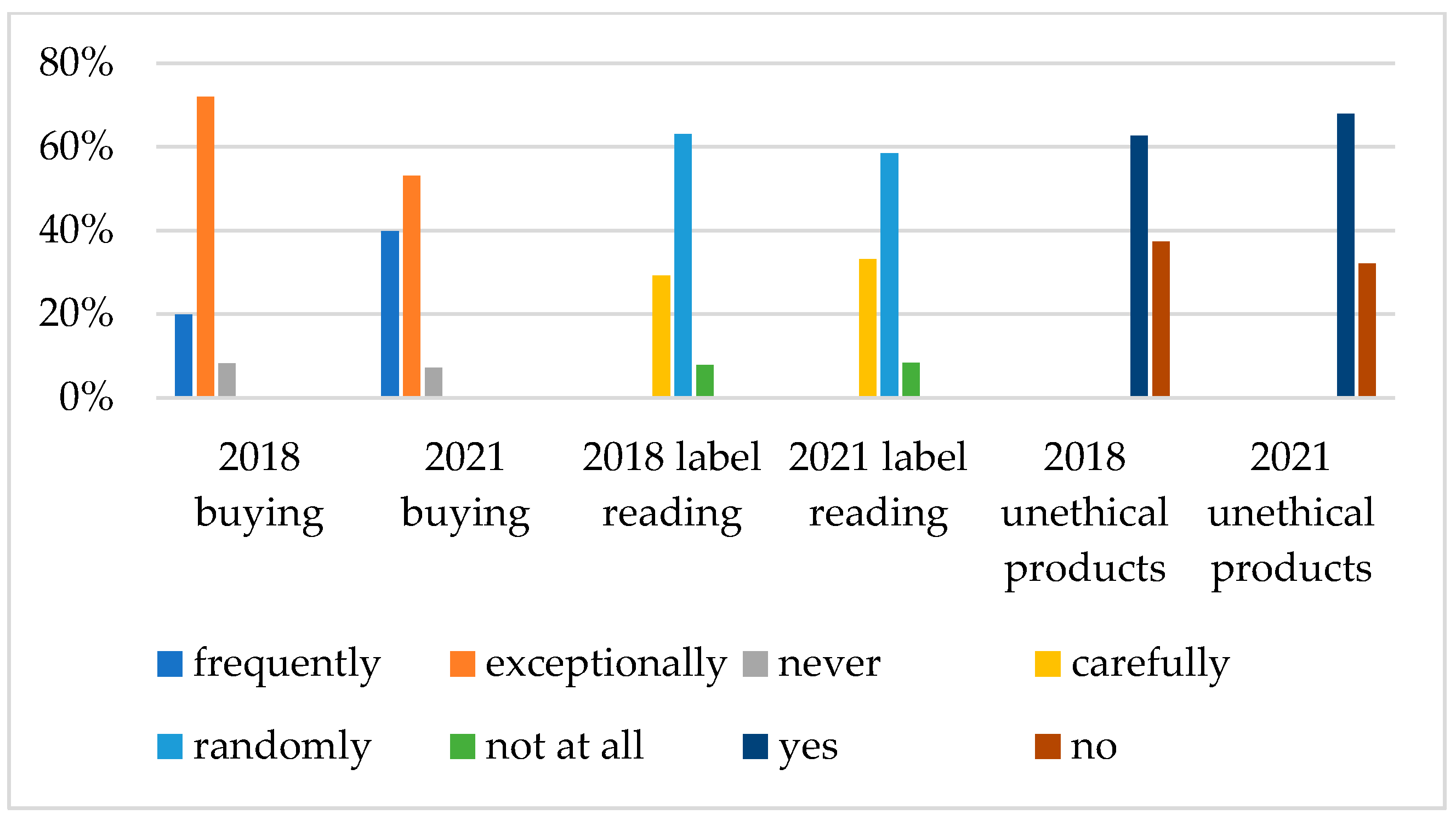

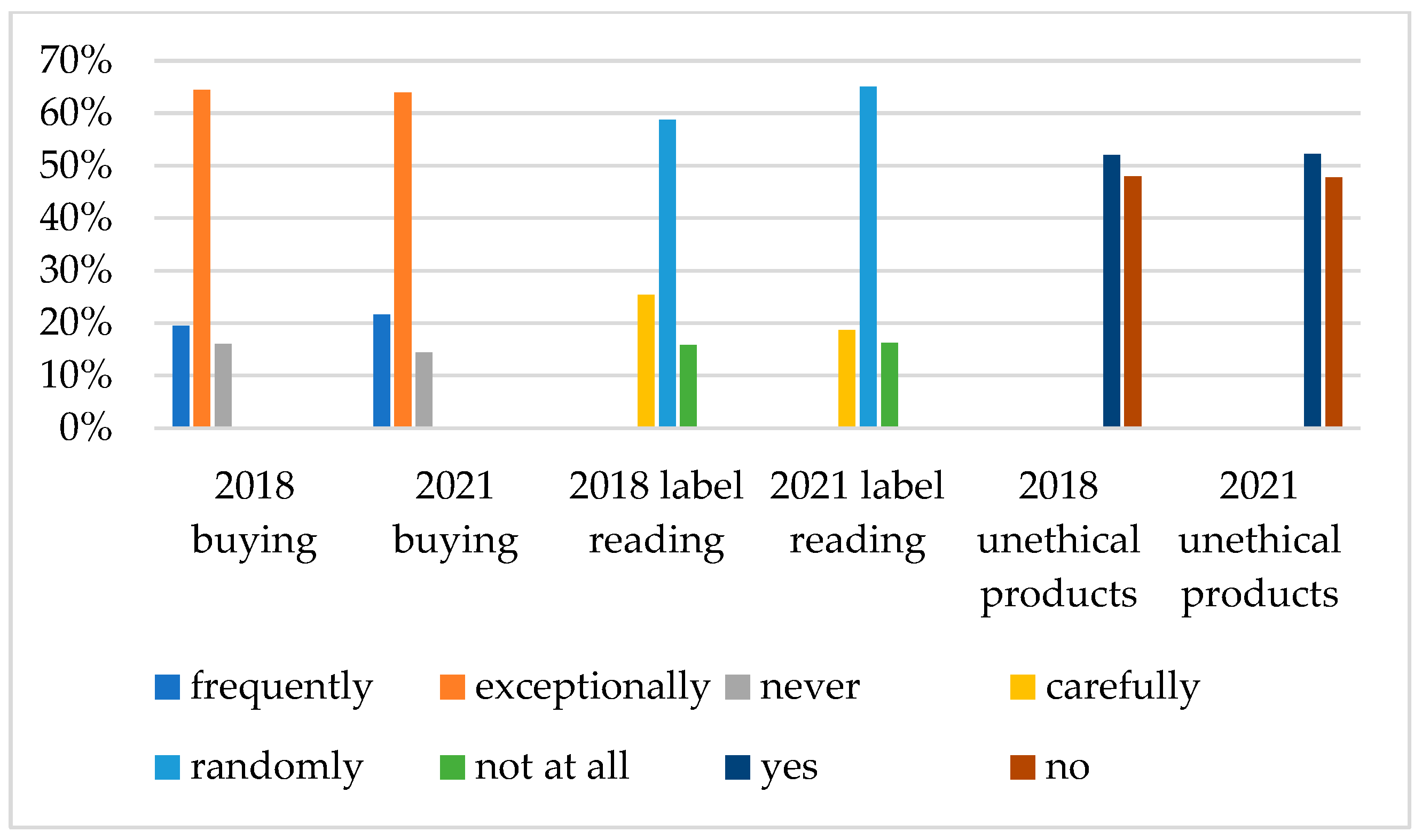

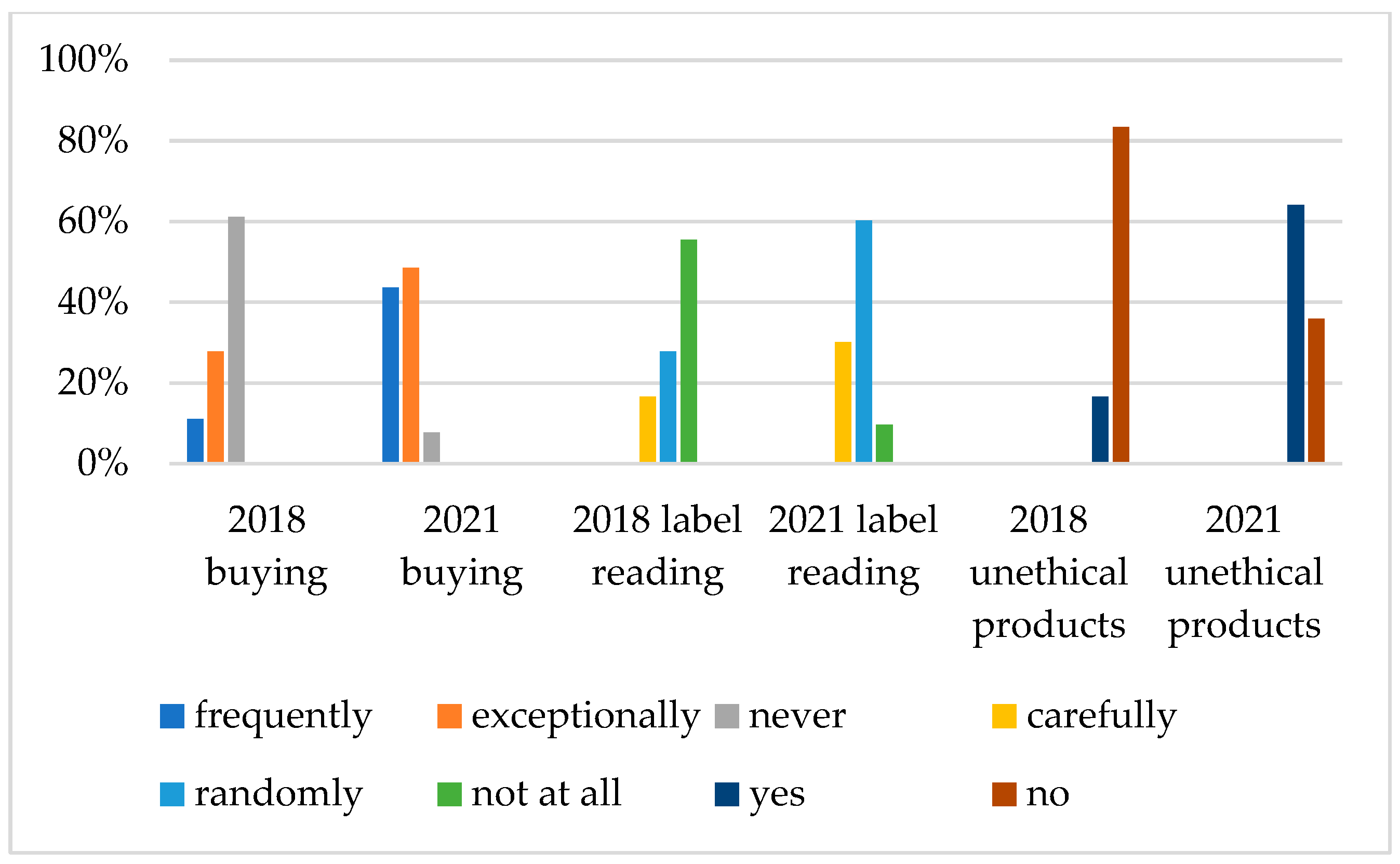

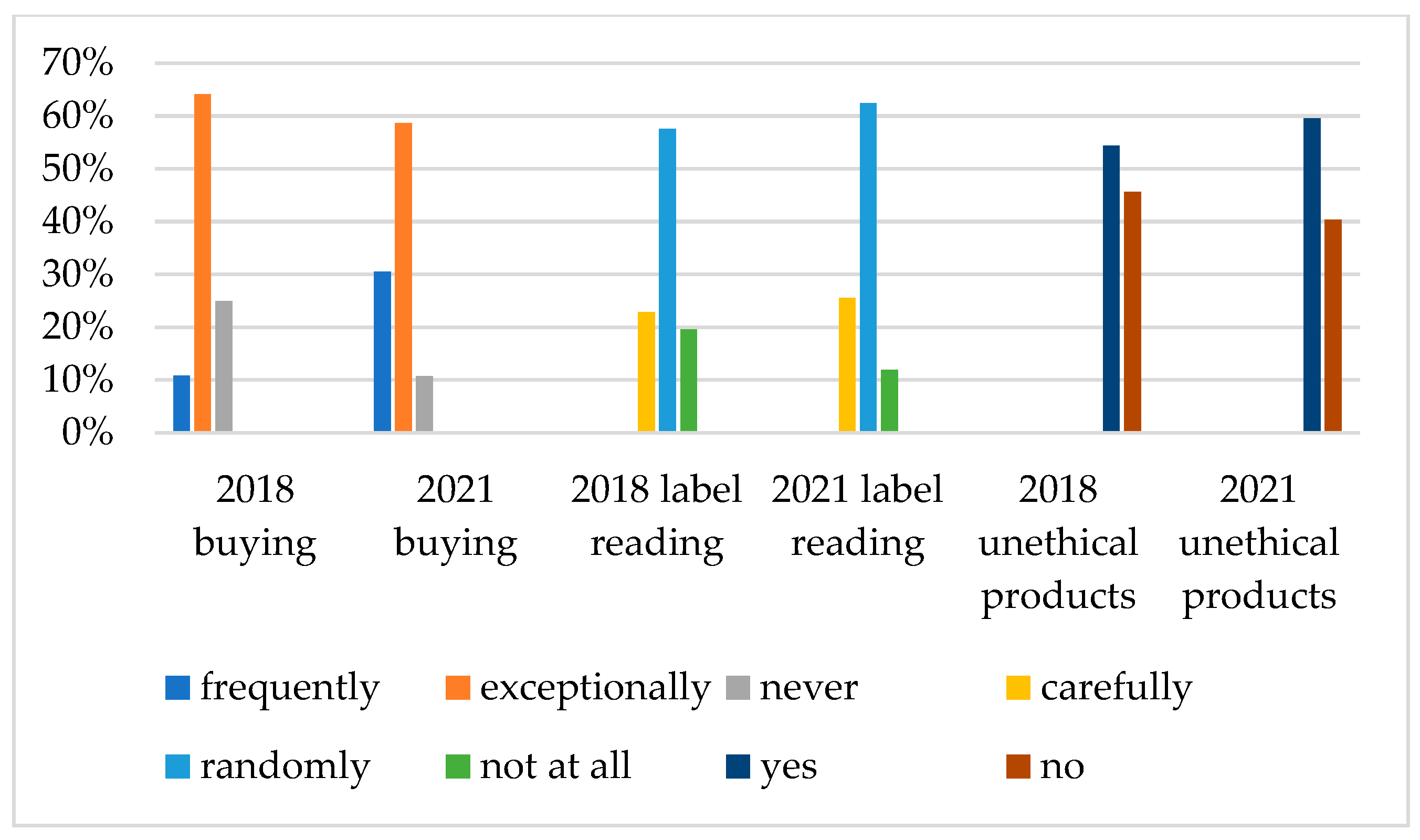

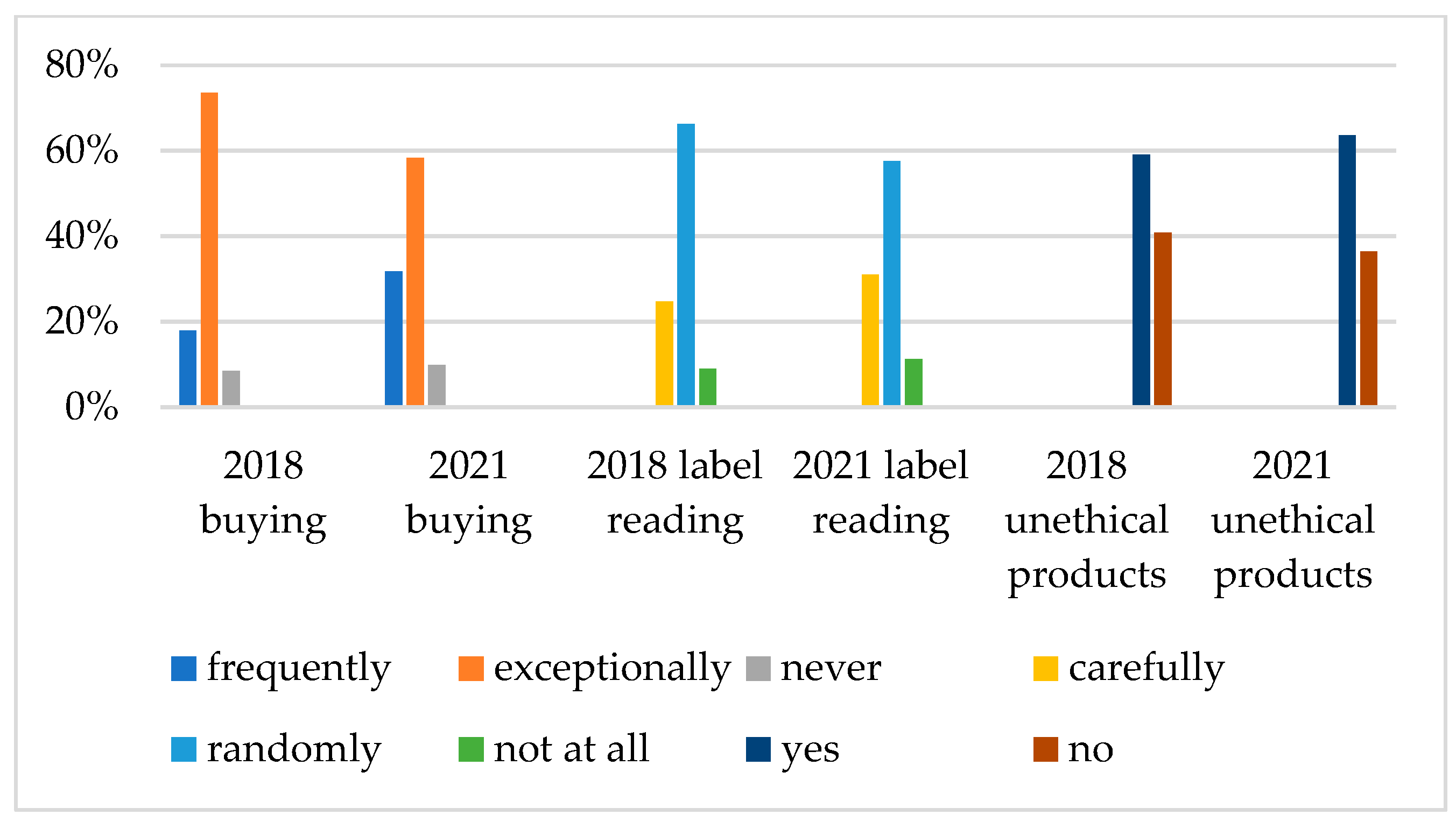

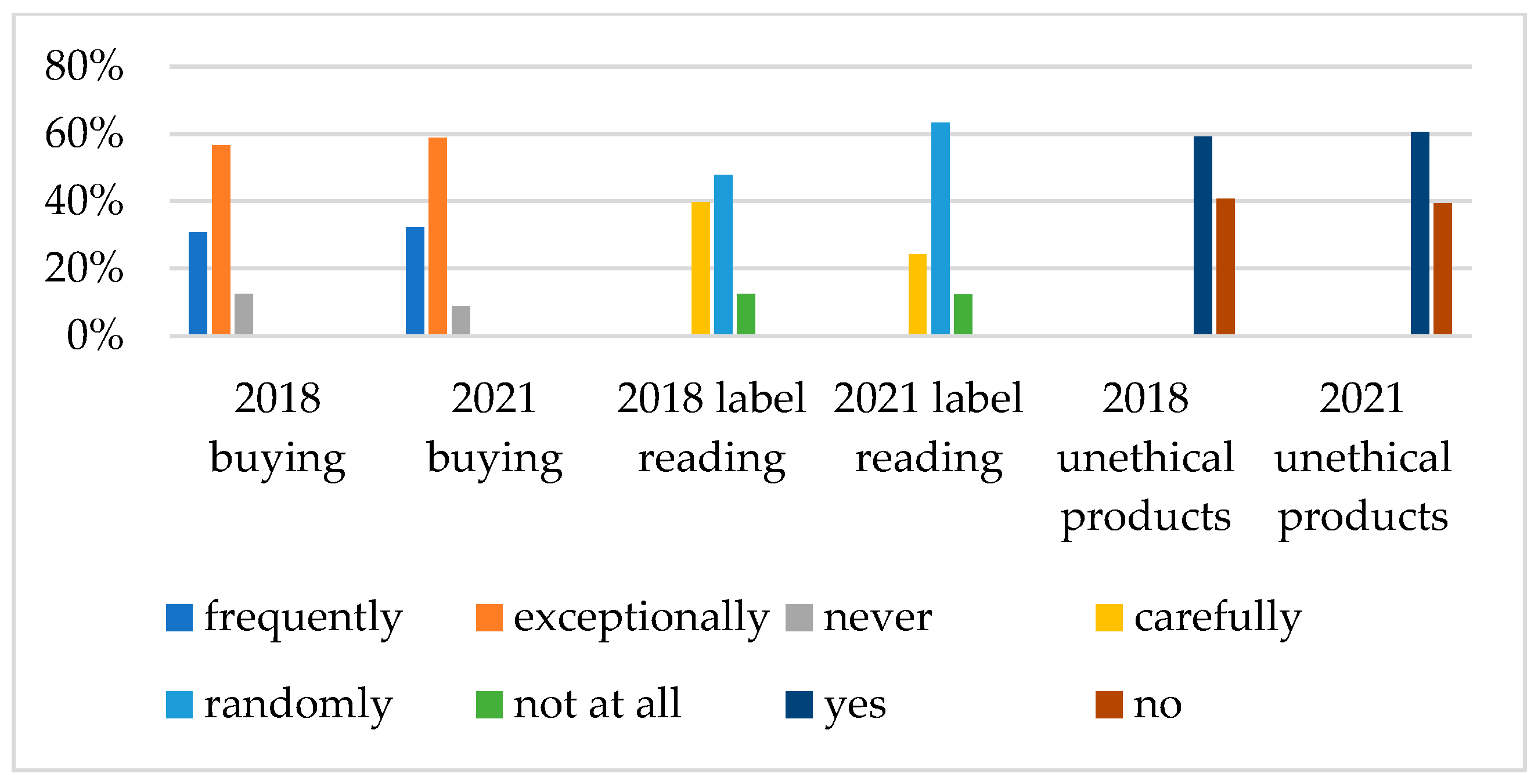

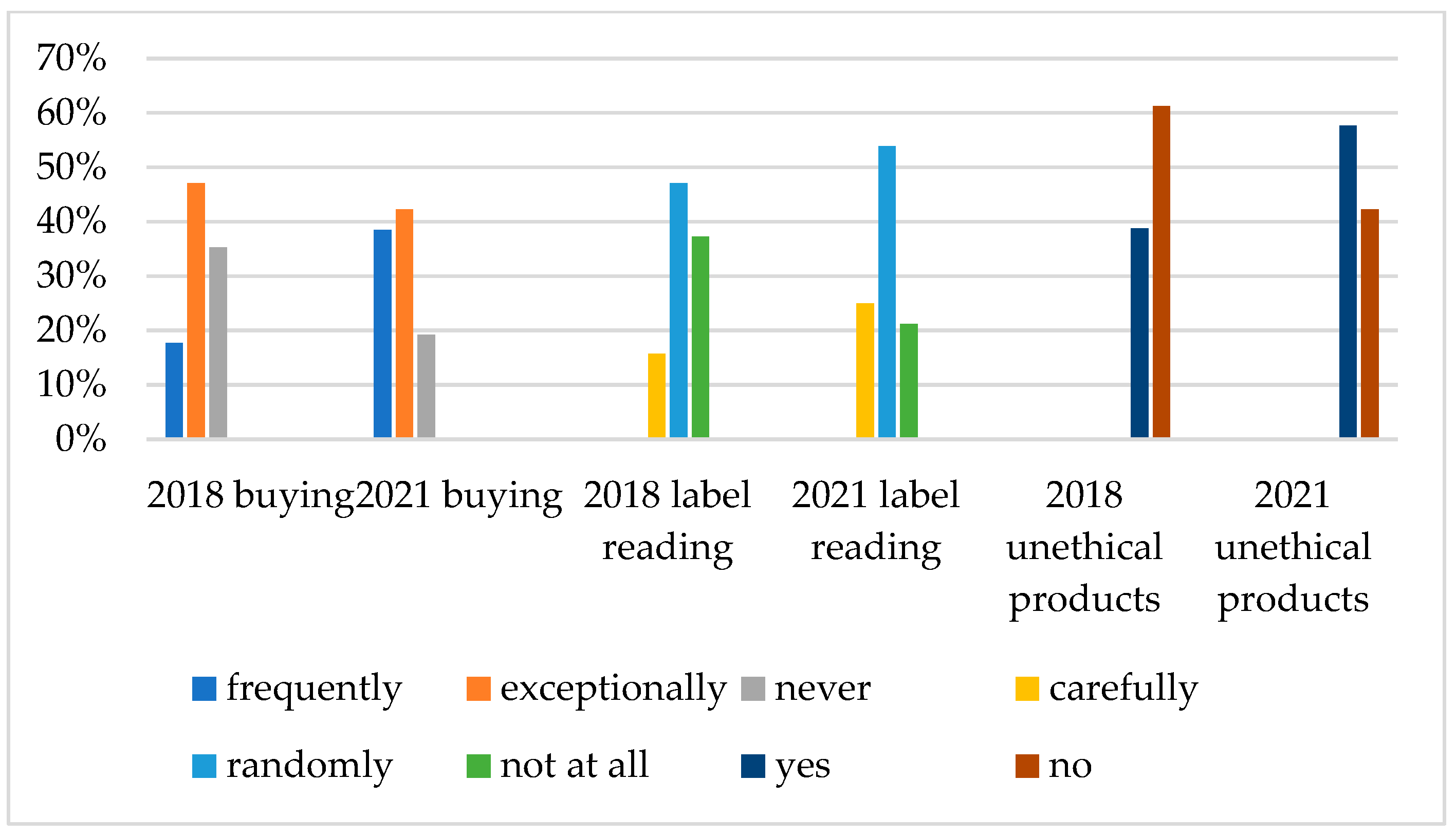

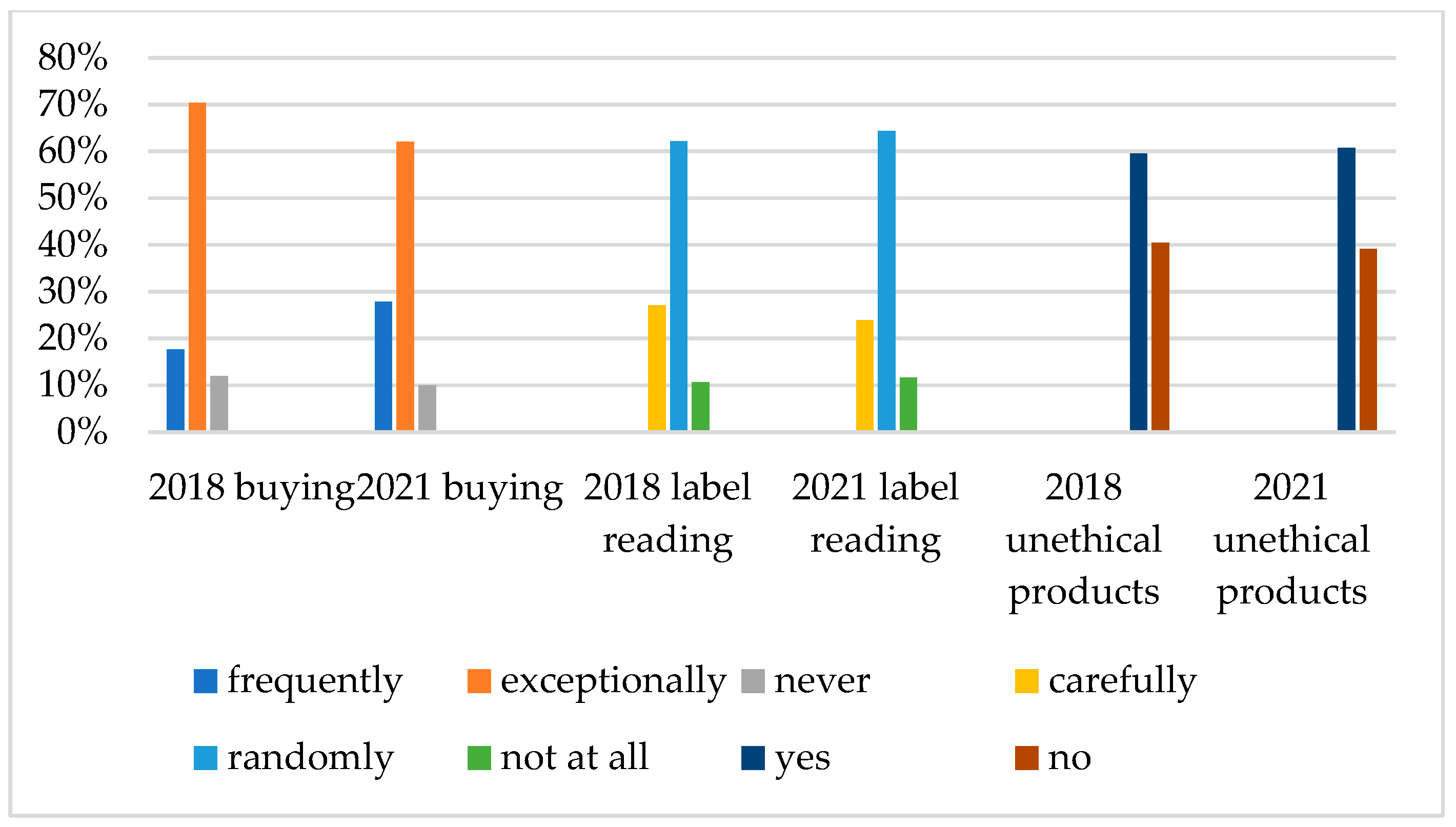

In the following summary of results, we will report and demonstrate only such cases of group comparisons where an OR greater than 2 occurred in tables and graphs. Among the differences before and after the pandemic (between the survey from 2018 and that from 2021), the increase in the number of women who shop regularly is the most interesting. While in 2018 the share of regular shoppers was the same for men and women, in 2021 it was 2.4 times higher for women than for men, taking into account occasional shoppers. The number of those who did not shop at all was the same in both surveys. Differences in behavior between men and women before and after the pandemic were also reflected in how often, and how carefully, they read labels. Men did not read labels more often than women, something which did not change between 2018 and 2021 (men read labels 2.22 times less often in 2018 and 2.11 times less often than women in 2021). When assessing respondents reading both attentively and superficially before the pandemic in 2018, their share was approximately the same for men and women. In 2021, however, the proportion of women who read carefully increased, so women read labels carefully 2.16 times more often than men. The situation is shown in

Table 2 and

Table 3 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

The evaluation according to economic status can be distorted, due to the different wording of the questions in both questionnaire surveys. Overall, frequent purchases increased, especially among respondents with a worse economic status. In the 2021 survey, respondents with an average income per household member of less than CZK 10,000 buy “responsible” products 1.77 times more often than those with an average income per household member of CZK 10,000 to 20,000.

If we compare the situation regarding label reading in 2018 according to the respondents’ economic status, then those with a very poor status who did not read labels at all were seen 5.14 times more often than those with a rather poor status, and those with a rather poor status who did not read labels at all were seen 2.44 times more often than those with a rather good status. On the other hand, respondents with a very bad status randomly read labels 3.53 times less often than those with a rather bad status. However, respondents with a rather good status read labels randomly 2.14 times more often than respondents with a very good status. However, if we compare these two groups for the careful reading of labels, we encounter this more than twice more often in respondents with a very good status. In other cases, the difference was not so significant; the OR was always less than 1.5. In 2021, the frequency of label reading between individual groups according to economic status equalized; the OR was smaller than 1.5 everywhere. Furthermore, the analysis focused on monitoring the boycott of unethical products by customers—the respondents. In 2018, the most significant difference was between respondents with very bad and rather bad economic status; the former boycotted unethical products almost six times less often than the latter. In 2021, the differences equalized; the OR was even, at most around 1.2. All these results are presented in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 and

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

When comparing the frequency of purchases according to respondents’ education, those with primary education most often do not buy “responsible” products at all; before the pandemic in 2018, this happened more than four times more often than those with secondary education, while after the pandemic, in 2021, their share decreased, so that it was only 2.13 times more frequent. This difference is compensated for by respondents who buy “responsible” products on an exceptional basis: those with secondary education made such purchases 2.67 times more often in 2018, and 2.24 times more often in 2021, than respondents with primary education. For regular shoppers, there are no such significant differences depending on education. Overall, however, their share in 2021 increased by 20% for respondents with primary education, 10% for secondary school students, and 15% for university students, compared to 2018.

Respondents with primary education did not read labels at all in 2018, almost five times more often than in those with secondary education, but they read them carefully twice less often. In 2021, the differences evened out, with the only OR which was just greater than 2 remaining for respondents with a secondary education, compared to those with primary education, who did not read labels at all; i.e., respondents with primary education did not read labels at all twice more often than those with secondary education.

Furthermore, respondents with primary education boycotted unethical products 2.32 times less often than those with secondary education. In 2021, the differences in this case also evened out.

There were no significant differences between respondents with secondary education and university degrees (OR approx. up to 1.7).

Childless respondents were also compared with those who had children, but in no case did we find a significant difference; the OR was always less than 1.35.

3.2. Hypothesis Verification

In order to enhance the findings of the research, four hypotheses were tested (

Table 9,

Table 10 and

Table 11). The presence of children in the family can significantly influence ethical shopping in general [

77] and, in this context, its intensity (H1). This influence may also be manifested in the change in attitudes (perceptions) towards ethical purchasing in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (H2).

The p-values are above 0.05; thus, we cannot reject H0, since there is no difference between the means. The H1 and H2 were not supported by the evidence. Pearson’s chi-squared test provided similar results, with levels of significance equal to a chi-squared test of 0.621 in the case of H1 and 0.250 in the case of H2.

The p-value is equal to 0.358, which is above 0.05; thus, we did not find evidence that the purchasing of ethical products is associated with income.

The results suggest that the attitude to purchasing ethical products depends on the income group. Specifically, there is a notable disparity in this regard between the people earning less than CZK 10,000 per month per person (group 1) on one side, and people earning CZK 10,000–20,000 per person (group 2) and 20,000–30,000 per person (group 3), on the other. Surprisingly, the attitudes of the less-affluent respondents (group 1), on average, changed more than those of groups 2 and 3. Group 4 did not show any significant differences from the other three groups.

4. Discussion

Many studies show a trend in consumer purchasing behavior towards more sustainable food attributes, even before the COVID-19 pandemic. These include consumers seeking more local, animal-welfare, fair-trade, organic, seasonal, and carbon-footprint foods [

89]. There is no doubt that the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has changed consumer behavior to buying even more of these foods with sustainable attributes [

90]. References [

91,

92] find that the COVID-19 pandemic has driven consumers to purchase sustainable products and that consumers now pay more attention to the environment and society, while [

93,

94] also report an increase in environmental concern because of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, individuals focused more on sustainable products, because maintaining health was their top priority [

95]. Previous studies have shown that maintaining and improving health are the main reasons for consuming sustainable products [

96]. Thus, prevailing attitudes towards health determine consumer behavior in purchasing more responsible and healthier products [

97]. As [

52] points out, the pandemic had a global and profound impact, and is likely to have a lasting effect on consumer behavior.

Many studies prove that there is a discrepancy between people’s attitudes towards sustainable products and their actual purchasing behavior [

98,

99,

100]. The research found that between 2018 and 2021, there was a significant shift in the intensity of the purchase of ethical products by women; namely, 20% of women and 2% of men bought more ethical products in 2021 than in the previous period. It can be said that, under the influence of changes and shopping restrictions, consumers’ unplanned and spontaneous shopping behavior changed to a search for more sustainable options [

101]. This represents a notable rise, particularly among women, which could partly be attributed to heightened interest in health and sustainability spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many other studies also suggest that women buy sustainable food more often [

102,

103]. The study [

90] result shows that during the lockdown, women were 1.517 times more likely to buy food with sustainable characteristics than men, compared to the situation before the lockdown. This finding is in line with previous research that suggested that women are more active in purchasing and consuming organic food than men, due to their lifestyle [

104,

105]. The reason may be that women pay more attention to their health, and consider sustainable food (e.g., organic food) to be healthier than conventional food [

106]. On the other hand, women are often responsible for purchasing food in the household, and, therefore, have a greater awareness of sustainable food [

103]. Indirectly related to this finding may be the fact that women are more concerned about climate change than men [

107]. One of the factors that can significantly support the rate of purchasing sustainable food is a credible certification of sustainable origin [

108]. Thus, a study [

90] analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on consumers’ purchase and consumption behavior from the viewpoint of sustainability showed that gender and age are relevant factors influencing sustainable behavior. On the other hand, research [

109] into the impact of COVID-19 on shopping behavior did not show any statistically significant differences between the genders. It also showed that consumers aged 40–59 were more likely to buy food with sustainable attributes during COVID-19 than those aged 18–39 [

90].

Income and age are common indicators of food spending behavior. An interesting finding from the conducted research is the increase in regular purchases of products belonging to the group of ethical products among respondents evaluating their economic situation as very bad. Here, the increase in this value reached 33% more in 2021 than in 2018. For the group of respondents in a bad economic situation, the increase was also significant: it was 20%. On the other hand, respondents with the best economic position recorded the smallest increase out of all the categories, only 1%, in comparison to the monitored years. At the same time, in some previous empirical studies conducted in Europe, income was identified as a principal factor influencing the purchase of organic food. Consumers with higher incomes are more likely to purchase larger amounts of organic food [

68,

110]. Compared to other products, sustainable products are usually more expensive. Attitudes towards risk in terms of financial impact have had a negative and significant impact on sustainable purchasing behavior. Compared to the situation before the COVID-19 pandemic, consumers who are more sensitive in this respect behaved less sustainably as a result of the lockdown [

90]. On the contrary, a study conducted in the United States of America did not find a connection between income, food consumption, and organic food purchasing behavior [

111]. In addition, another study indicated that income has no effect on the regularity of organic food consumption, but that it influences individual expenditure on organic food [

112].

One of the monitored parameters that influenced the level of purchase of ethical products was the household structure, specifically the presence of children in the family. Families with children regularly buy sustainable products in 21% of cases, and families without children in 19% of cases. Between 2018 and 2021, the intensity of repeated regular purchases increased by 12 or 13%. Previous research also corroborates this finding, demonstrating that consumers with children are more inclined to purchase sustainable products [

113]. Research [

82] also indicated that the presence of children in the household is positively associated with the likelihood of higher organic-food consumption. Research [

18] showed that households with five members were 2.551 times more likely to purchase more food with sustainable elements than those with one member, compared to the situation before the COVID-19 pandemic. Income, household size and family composition (with children) positively affect food expenditure [

114]. The study also found that household size significantly affects sustainable consumption, suggesting that households with four members consume healthier food and waste less food than people living alone, compared to the situation before the COVID-19 [

90].

In summary, during the COVID-19 pandemic, consumers were more likely to buy, and pay higher prices for, sustainable products, to pay more attention to environmental issues, and to behave more sustainably [

115]. The magnitude of change was strongly influenced by socio-demographic variables such as gender, age, income, and presence of children in the family.

As a prerequisite for introducing innovations in retail, it is also necessary to focus on the effects of online shopping in the digital environment. The development of the digitization of retail sales was supported precisely by the pandemic situation, which meant a complete lockdown, i.e., the restriction on visiting brick-and-mortar stores for consumers. Online shopping has significantly impacted the consumers’ purchasing decision-making process in four ways: substitution, complementarity, modification, and neutrality [

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124]. Each approach has profoundly shaped consumer buying behavior, demonstrating rapid adaptation to emerging retail concepts in the online landscape.

For example, Weltevreden and Rietbergen (2007) hypothesize that favorable perceptions of downtown grocery shopping weaken consumers’ desire to shop online [

118]. In contrast, an empirical study in the city of Nanjing reveals that in-store shopping positively affects online shopping [

125]. While these empirical studies yield varying outcomes, a consensus has yet to be established. Thus, it is evident that consumers have altered their approach to grocery shopping in brick-and-mortar stores, and have begun to embrace online grocery shopping via new digital platforms.

Another illustration of the shift in consumer food-shopping behavior can be seen in the findings from Guangzhou. Following the pandemic outbreak, there was a modest rise in online shopping frequency among residents, accompanied by an increase in individual spending during COVID-19. Notably, the expenditure index for the online shopping population climbed to 687.88, marking a 12.85% increase from the typical level of 609.53.

Compared to normal times, the COVID-19 pandemic has widened the gap in online-shopping frequency between central-urban and suburban areas, while slightly narrowing the gap in online-shopping spending between the two areas. In general, the frequency of online shopping and spending in central urban areas was higher than in suburban areas during normal times. Residents’ spending on online shopping has increased significantly. This result can be partially attributed to MICT’s well-equipped infrastructure and logistics distribution systems in central urban areas. However, the difference in the online-shopping frequency index of individuals in the city during the pandemic reached 0.28, which is about three times more than in normal times (0.09). Suburban areas with poorly equipped MICT infrastructure and logistics distribution system forced residents to purchase more items for each online purchase, resulting in a much lower online-shopping frequency than in central urban areas. However, the difference in the online-shopping expenditure index for residents in the central-urban compared with the suburban areas reached 22.82, which is 18.88% less than in the normal time (28.13). COVID-19 and the subsequent self-quarantine and lockdown policies have forced individuals to purchase items online at a higher rate, narrowing the gap in online-shopping spending between inner-city and suburban areas. This result highlights the fact that the Internet played the role of a geographic balancer, which contradicted the path-dependence theories, from the Internet industry perspective [

126].

The 2019 pandemic so significantly affected consumer behavior, that the consumers had to find parallel ways to satisfy their needs through purchases. Retailers also had to respond swiftly to this scenario, to avoid jeopardizing their business stability. As part of the solution to this turbulent phenomenon, innovative procedures were implemented, which the retail industry used in response to the pandemic purchasing restrictions. The retail industry adopted innovative procedures to respond to this turbulent phenomenon. One of the first innovative approaches was introducing a hybrid-store concept. This concept involved establishing an online store on a digital platform for ordering and importing goods, representing a blend of traditional- and digital-retail strategies. The restrictions and hygiene regulations of the global coronavirus crisis set new rules for interpersonal relationships. They changed the way of shopping, via e-shops, with the support of functional logistics for delivering ordered food. The innovation lay in introducing the ‘cargo on-site’ product, which entailed the retailer’s cooperation with the distribution collection system. In the Czech Republic, retail platforms like košík.cz, rohlík.cz, and damejídlo.cz have established their reliability.

New trends described by McKinsey determine innovative businesses in retail. According to a McKinsey study, seven new trends are emerging in grocery retail:

New innovative providers of online-grocery solutions are constantly entering the market. The business model needs to be segmented and streamlined to make a profit; for example, through home deliveries, click-and-collect, or collection points. Thinking that online food sales will remain a niche market forever is a mistake.

Some brick-and-mortar retailers are becoming creative, and offering more online-shopping options. As a result, the line between online and offline sales is blurring. The customer wants to have fun in the future. For example, customers can order online and pick up the item in the store. Virtual stores are integrated physically into the supermarket. In addition, more and more “micro-stores” are emerging as outlets for a given business, allowing customers to physically try out products before purchasing them online.

The importance of digital marketing, social media, and local services is also growing. This approach allows better customer communication, and can incorporate customer ideas into the whole process.

For the customer approach, adaption to customer requirements and customer-relationship management is constantly improving. The reasons are extensive big data analysis and applications, sophisticated customer-loyalty programs, “social shopping,” and local services.

Advances in supermarket self-service checkouts and the “digital wallet.” Communication at the point of sale enables the use of smartphones for payment (the Scan & Go application).

The use of tablets for employee knowledge and training, product information, and product customization is increasing.

Through dynamic price management, brick-and-mortar grocery retailers are forced to adjust their prices to match online prices and to remain competitive.

Today, online and offline customers are often served from two different logistics systems. How to achieve synergy here has yet to be satisfactorily resolved and requires innovation in the logistics organization. The challenge of efficient “last minute” processing also arises at the technological level. Innovative concepts for “last-minute” delivery of goods are still emerging, but they could help to streamline the last leg of the delivery of goods to the customer, in the opinion of the study’s authors. “Click and collect” concepts already work as an alternative to cost-intensive distribution in the last delivery stage to the customer. With click-and-collect, the customer orders online and selects a pick-up location and time. In general, this industry approach is the most cost-effective solution, especially for traditional retailers entering food retail, for example, in rural areas.

The so-called “dark stores” are used to process purely e-commerce transactions. They resemble a supermarket, but serve as an online picking center or enable “click-and-collect” concepts. According to the study, logistics service providers will play a significant role in food delivery, mainly to alleviate pressure on urban areas at the “last-minute” food returns, and in the pooling of regional food deliveries. Deliveries using drones and containers have been a reality, at least in America, since 2016. In San Francisco, the grocery chain 7-Eleven is already delivering their purchases to selected customers by drone. In San Diego, Uber wants to deliver McDonald’s Burgers by drone in the future. However, the drones must land in a secure zone, and then the deliveries will be delivered to the customer by a courier.

The above-mentioned innovative formats of retail sales can be considered as effective challenges for retail; within the framework of their sustainability, competitiveness, and efficiency, they will be forced to adopt innovative solutions for their sales formats, with the aim of creating a comfortable and interactive environment for consumers, which will simplify and improve the purchase even more. The reality of the current digitization of retail is inexorable, with the younger generation being significantly influenced by social media. They adapt rapidly to digital communication, and it is evident that innovations will predominantly occur within hybrid-business platforms. These platforms merge modern brick-and-mortar retail with digital consumer engagement, underpinned by highly efficient logistics that ensure the delivery of goods to the designated place.

In terms of innovation and sustainability from a retail perspective, digital communication platforms with consumers are beginning to dominate. Among the current modern trends in the field of communication innovations in the field of retail sales is the use of cloud systems with a relevant product offer. Relevance can be understood as helping consumers with everyday problems. Well-communicated differentiation is the cornerstone of innovative strategy and business success. For the purchase of sustainable products, another innovative trend is Connected CPG and personalization. Research has shown that female consumers and households with children tend to buy sustainable products more than households without children. This situation can be changed by an innovative element in the form of a proposal for a mix of dietary supplements based on the completion of a diagnostic online questionnaire. This approach creates a tailor-made product delivered to consumers, with perfectly functioning logistics; this sales approach can lead many consumers to sustainable products. In order to strengthen the retail business, it is important to merge the digital and physical worlds by creating an innovative environment that can connect both worlds; e.g., technology working in augmented reality [

114].

5. Conclusions

The research reflects the behavior of consumers around purchasing sustainable products in 2018, and these findings are compared to 2021; i.e., differences and changes in consumption behavior before and after the COVID-19 pandemic in the conditions of the Czech Republic. The study showed that the purchasing behavior of consumers has changed; consumers have discovered the benefits of many online activities, and they approach purchasing more responsibly. The online environment provides them with greater shopping comfort, and the ethical approach of consumers to shopping, including access to food waste, grows even more. Retail reacts to this with innovative procedures, going beyond traditionalism, and focusing fully on the digital-marketing communication area. The essence of this communication is the active involvement of the consumer in the sales process.

Consumers have also changed their preferential approach to purchases. Women buy sustainable food more often; they are more interested in labels. The study showed that, among respondents who rate their economic situation poorly, they regularly buy products belonging to the group of ethical products. Also, families with children are more interested in buying sustainable products, and consumers with higher incomes buy more organic food. These research findings contradict a study in the United States that found no association between income, consumption, and organic-food purchasing behavior.

The obtained results can contribute to the expansion of the literature on the issue of sustainable consumer behavior. A better understanding of consumer behavior is especially important for changing the approach of retail companies, marketing specialists, and, for example, policymakers, in raising awareness of products that have a lower negative impact on the environment. Thus, it is crucial for retailers, both large and small, to comprehend how their consumers will respond and act, to identify the factors significantly influencing their purchasing decisions, and to adapt to these trends through an innovative approach to consumers.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite the contribution of this study, this study has some limitations. Firstly, the data rely on self-reported information instead of observed behavior. Self-reported items may be a limitation with respect to data quality, e.g., social desirability bias and lack of memory. One of the limitations of this research may be that the population sample was made up mainly of students and, therefore, needs to cover other demographic groups more broadly. For this reason, caution should be exercised when generalizing the results, given that a higher level of education is usually associated with higher consumption of sustainable products. Although the study offers valuable insights, its generalizability may be limited, due to its geographical focus on the Czech Republic only. Transferability to a global context may be limited, for this reason. A limitation is that the comparative research between 2018 and 2021 did not take place among an identical group of people, and other unknown factors may also influence the results found. In the realm of social distancing, prompted not only by the COVID-19 pandemic, but also by potential future pandemics, considerable scope remains for researching the short- and long-term changes in individual-purchasing and consumption behaviors. Therefore, further research could investigate whether this change in consumption and purchasing behavior is long-term in this global crisis, and explore other factors influencing consumption and purchasing behavior. Qualitative research could also complement and continue the investigation of this issue, showing the deeper context of the influence of ethical aspects on consumer purchasing decisions. The retail industry is presently at a juncture where it must ready itself for the advancements in artificial intelligence, which will undoubtedly soon influence consumer purchasing decisions. Consequently, there is additional potential for research into how the sustainability of retail sales, particularly within ethical food shopping, will be impacted by the innovative use of artificial intelligence. This research should also explore the effects of such technology on the interpersonal interactions between consumers and retailers during food purchases.