Innovation as a Tool for Sustainable Development in Small and Medium Size Enterprises in Slovakia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Subject and Problem

3. Materials and Methods

- M—Mandatory requirements or basic (threshold) features—these requirements must be met. They are very important from the point of view of user´s attitudes.

- O—One-dimensional requirements or performance features—are linearly dependent on fulfillment and user satisfaction.

- A—Attractive requirements or excitement features- user´s r satisfaction grows exponentially with the fulfillment of requirements.

- I—Indifferent requests do not affect user satisfaction.

- R—The exact opposite requirements present conflicting user´s attitudes.

- Q—Represents ambiguous requirements, where the user´s cannot express himself clearly.

- i.

- innovations

- ii.

- ecological innovations

- iii.

- the importance of innovations for the company’s strategy

- iv.

- implementation of innovations

- v.

- product innovation

- vi.

- process innovations

- vii.

- increasing labor productivity through innovation

- viii.

- increase in turnover through innovation

- ix.

- reducing environmental impacts through innovation

- x.

- growth of competitiveness through innovation

- xi.

- increasing the company’s market share through innovation

- xii.

- increasing profits through innovation

- xiii.

- cost reduction through innovation

- xiv.

- compliance with standards (laws) through innovations

- xv.

- high costs for the implementation of innovations

- xvi.

- profitability of investments in innovations and the innovation process

- xvii.

- innovation risk

- xviii.

- experience and know-how with the implementation of innovations and the innovation process

- xix.

- workforce in the implementation of innovations

- xx.

- cooperation in the implementation of innovations

- xxi.

- information for the implementation of innovations and their support

- xxii.

- financial means for innovation and the innovation process

- xxiii.

- bureaucracy

- n—sample respondents

- N—the number of small and medium enterprises in Slovakia—634,309

- e—permissible margin of error—10%

- p—dispersion—50%

- -

- tested, which we formulated as null—H0

- -

- and the alternative, which we label H1, see Table 4.

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Study Limitations and Recommendations for Future Work

7. Conclusions

- -

- companies have a positive attitude toward innovation as an important factor in sustainable development,

- -

- companies focus on frugal innovations characterized by cost reduction, focusing on basic functions, standards, laws, and performance optimization,

- -

- companies perceive a number of barriers when implementing innovations supporting sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ivanička, K. Trvalá Udržateľnosť Inovácií v Rozvoji Slovenska; Wolters Kluwer: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Loučanová, E.; Olšiaková, M.; Dzian, M. Suitability of innovative marketing communication forms in the furniture industry. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen Res. Publica Slovaca 2018, 60, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Lovciová, K. Zelené Inovácie ako nástroj podpory environmentálneho podnikateľského prostredia Slovenskej republiky. Econ. Inform. 2021, 19, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rusko, M. Inovácie a technológie v kontexte trvalo udržateľného rozvoja. In Proceedings of the Nástroje Environmentálnej Politiky—Recenzovaný Zborník z IX. Medzinárodnej Vedeckej Konferencie, Bratislava, Slovakia, 30 January 2019; pp. 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Calza, F.; Parmentola, A.; Tutore, I. Types of Green Innovations: Ways of Implementation in a Non-Green Industry. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loučanová, E.; Olšiaková, M.; Štofková, J. Open business model of eco-innovation for sustainability development: Implications for the open-innovation dynamics of Slovakia. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbarma, J.; Choi, Y.; Yang, F.; Lee, H. Exports as a new paradigm to connect business and information technology for sustainable development. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, V.; Crespi, F. Environmental regulation and the export dynamics of energy technologies. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 66, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvaj, I.; Drbúl, M.; Bůžek, M. Sustainability in Small and Medium Enterprises, Sustainable Development in the Slovak Republic, and Sustainability and Quality Management in Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiľa, M.; Kučera, J. Súčasný stav inovačnej výkonnosti Slovenska a slovenských MSP. Produkt. A Inovácie 2015, XVI, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jeck, T. Ekologické Inovácie na Slovensku: Stav, vývoj a politiky. Životné Prostr. 2018, 52, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Benešová, D.; Kubičková, V.; Michálková, A.; Krošláková, M. Innovation activities of gazelles in business services as a factor of sustainable growth in the Slovak Republic. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2018, 5, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P. The sustainability circle: A new tool for product development and design. J. Sustain. Prod. Des. 1997, 2, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission. Competitiveness and Innovation Framework Programme. 2014. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/cip (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Tian, P.; Lin, B. Promoting green productivity growth for China’s industrial exports: Evidence from a hybrid input-output model. Energy Policy 2017, 111, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loučanová, E.; Šupín, M.; Čorejová, T.; Repková-Štofková, K.; Šupínová, M.; Štofková, Z.; Olšiaková, M. Sustainability and branding: An integrated perspective of eco-innovation and brand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degato, D.D. Innovation and paths to social-ecological sustainability. Risus-J. Innov. Sustain. 2017, 8, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loučanová, E.; Nosáľová, M. Eco-innovation performance in Slovakia: Assessment based on ABC analysis of eco-innovation indicators. BioResources 2020, 15, 5355–5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimon, S.A.; Dumiter, F.C.; Baltes, N. Financial Sustainability of Public Pension System. In Financial Sustainability of Pension Systems: Empirical Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Dumiter, F.C.; Nicoară, Ș.A.; Boiță, M.; Loučanová, E.; Stofkova, K.R. Financial, Economic, and Social Sustainability Aspects of Pension Systems. Econom. Approaches Cent. East. Eur. 2023. pre-print. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. The Decade of Action for the Sustainable Development Goals: Sustainable Development Report 2021. Published Online at sdgindex.org, Cambridge, UK. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/ (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- To, C.K.; Martinez, J.M.G.; Orero-Blat, M.; Chau, K.P. Predicting motivational outcomes in social entrepreneurship: Roles of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and situational fit. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 121, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, C.K.M.; Chau, K.P. Characterizing sustainability materiality: ESG materiality determination in technology venturing. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2022, 1, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbone, D.; Maroun, W. Materiality in an integrated reporting setting: Insights using an institutional logics framework. Br. Account. Rev. 2020, 52, 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, B.E.; Eilifsen, A.; Glover, S.M.; Messier, W.F., Jr. The effect of audit materiality disclosures on investors’ decision making. Account. Organ. Soc. 2020, 87, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, D.; Acosta, M.; Fernández, A. Attitudes to innovation in peripheral economic regions. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunrinde, A. The Effectiveness of Soft Skills in Generating Dynamic Capabilities in ICT companies. ESIC Market 2022, 53, e286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Tróchez, D.X.; Cerón Ríos, G.M.; Rivera Martínez, W.F. Intrapreneurship in Small Organizations: Case Studies in Small Businesses. ESIC Market. Econ. Bus. J. 2021, 52, 135–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J. Research on the effect of enterprise financial flexibility on sustainable innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyagadza, B. Sustainable digital transformation for ambidextrous digital firms: Systematic literature review, meta-analysis and agenda for future research directions. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2022, 1, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euractiv Slovensko. Životné Prostredie. Available online: https://www.europskaunia.sk/zivotne-prostredie (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- OECD. Prehlady Environmentálnej Výkonnosti OECD: Slovenská Republika. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/env/country-reviews/49196350.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- de Miguel, P.M.; Martínez, A.G.; Montes-Botella, J.L. Review of the measurement of Dynamic Capabilities: A proposal of indicators for the automotive industry. ESIC Mark. 2022, 53, e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knošková, Ľ.; Kollár, V. Faktory úspešnosti inovačných aktivít firiem pôsobiacich na Slovensku. Ekon. Časopis 2011, 59, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Cort, T.; Esty, D. ESG standards: Looming challenges and pathways forward. Organ. Environ. 2020, 33, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeck, T. Ekologické inovácie: Teoretické a hospodársko-politické súvislosti [Eco-innovation: Theoretical and economic-political context]. Inst. Econ. Res. 2012, 42, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lesáková, Ľ. Evaluating Innovation Activities in Small and Medium Enterprises in Slovakia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2009, 110, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madáč, J.; Mateides, A.; Pohančaník, P. Spokojnosť Zákazníka; EF UMB: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, N.; Singh, A.R. Sustainable supplier selection criteria classification for Indian iron and steel industry: A fuzzy modified Kano model approach. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2020, 13, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Jiao, R.J.; Yang, X.; Helander, M.; Khalid, H.M.; Opperud, A. An analytical Kano model for customer need analysis. Des. Stud. 2009, 30, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodpasture, J. Quantitative Methods in Project Management; J. Ross Publishing: Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2003; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, A.; Pourhamidi, M.; Antony, J.; Hyun Park, S. Typology of Kano models: A critical review of literature and proposition of a revised model. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2019, 30, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, C.; Blauth, R.; Boger, D.; Bolster, C.; Burchill, G.; Dumouchel, W.; Pouliot, F.; Richter, R.; Rubinoff, A.; Shen, D.; et al. Kano’s methods for understanding customer-defined quality. Cent. Qual. Manag. J. 1993, 2, 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Slovak Business Agency. Malé a Stredné Podnikanie v Číslach v Roku 2021, Slovakia: Bratislava, SBA, 2020. Available online: https://monitoringmsp.sk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MSP_v_cislach_2021_final.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Sample Size Calculation. Available online: https://fmk.sk/vzorka/ (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Soukup, P. Nesprávná užívání statistické významnosti a jejich možná řešení. Data A Výzkum–SDA Info. 2010, 4, 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstein, R.L.; Lazar, N.A. The ASA statement on p-values: Context, process, and purpose. Am. Stat. 2016, 70, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollár, T. Aplikácia zhlukovej analýzy vo výskume potreby kognitívnej štruktúry. In Metódy Empirickej Psychológie; FSVaZ UKF: Nitra, Slovakia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kožiak, R.; Suchý, M.; Kaščáková, A.; Nedelová, G. Využitie zhlukovej analýzy pri skúmaní medziregionálnych rozdielov. In Proceedings of the 17th International Colloquium on Regional Sciences, Hustopece, Czechy, 8–20 June 2014; pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kliuchnikava, Y. The impact of the pandemic on attitude towards innovation among smes in the Czech republic and Poland. Int. J. Entrep. Knowl. 2022, 10, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, T. Marketing and organisational innovations in entrepreneurial innovation processes and their relation to market structure and firm characteristics. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2010, 36, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyrauch, T.; Herstatt, C. What is frugal innovation? Three defining criteria. J. Frugal Innov. 2017, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyrauch, T.; Herstatt, C. Frugal innovation–What is it? Criteria for frugal innovation. In Proceedings of the R&D Management Conference, Cambridge, UK, 3–6 July 2016; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, R.R.; Banerjee, P.M.; Sweeny, E.G. Frugal innovation. J. Manag. Glob. Sustain. 2013, 1, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, M. Sustainable frugal innovation-The connection between frugal innovation and sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Yang, Y.; Dooley, K.; Chae, S. Trading-off innovation novelty and information protection in supplier selection for a new product development project: Supplier ties as signals. J. Oper. Manag. 2020, 66, 933–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenihan, H.; McGuirk, H.; Murphy, K.R. Driving innovation: Public policy and human capital. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovak Business Agency. Inovačný Potenciál MSP na Slovensku, Bratislava, SBA, 2020. Available online: https://monitoringmsp.sk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Inova%C4%8Dn%C3%BD-potenci%C3%A1l-MSP-na-Slovensku-1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Direction, S. Delivering sustainable innovation: A Positive Attitude. Strateg. Dir. 2009, 25, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Harini, C.; Priyanto, S.H.; Ihalauw, J.J.; Andadari, R.K. The role of ecological innovation and ecological marketing towards green marketing performance improvement. Manag. Entrep. Trends Dev. 2020, 1, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabynskyi, I.; Horin, N.; Ukrayinets, L. Barriers and drivers to eco-innovation: Comparative analysis of Germany, Poland and Ukraine. Ekon.-Manazerske Spektrum 2017, 1, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Lim, K. Using Kano model to understand an effect of specialization and perceived risk on demand for services in marine tourism. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madzík, P.; Budaj, P.; Mikuláš, D.; Zimon, D. Application of the Kano model for a better understanding of customer requirements in higher education—A pilot study. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Research Issue: Perception of Innovation as a Tool for the Developing of Sustainability by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Slovakia. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Research objective 1 | To find out whether small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia consider innovation as a tool for developing sustainability | Hypothesis 1: Innovations are a tool for developing the sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia. |

| Research objective 2 | To find out whether small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia implement innovations for compliance with standards (law) related to sustainable development. | Hypothesis 2: Small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia will implement innovations for compliance with standards (law) related to sustainable development. |

| Research objective 3 | To find out whether small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia encounter various barriers when introducing innovations as a tool for sustainable development. | Hypothesis 3: Small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia encounter various barriers when introducing innovations as a tool for sustainable development. |

| Factors n = 217 | Specification | Multiplicity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute | Relative | ||

| Type business | Self-employed | 125 | 57.60 |

| Limited liability companies | 76 | 35.02 | |

| Stock company | 14 | 6.45 | |

| Cooperative | 2 | 0.93 | |

| Number of employees | 0–9 | 161 | 74.19 |

| 10–49 | 44 | 20.28 | |

| 50–249 | 12 | 5.53 | |

| 250 and more | 0 | 0.00 | |

| NACE | Section A—Agriculture, forestry, and fishing (A 01–03) * | 28 | 12.90 |

| Section C—Manufacturing (C.10–11; C.14–15; C.29; C.30; C.33) * | 25 | 11.52 | |

| Section F—Construction (F.41-F.43) * | 38 | 17.51 | |

| Section G—Wholesale and retail trade (G.45–46) * | 39 | 17.97 | |

| Section H–J—Transport, information, and communication (H.49–53; J.58–63) * | 18 | 8.29 | |

| Section I—Accommodation and catering sector (I.55–56) * | 4 | 1.86 | |

| Section K–N—Business services (K.64–66; L.68) * | 52 | 23.96 | |

| Section P–S—other services (S.94–96) * | 13 | 5.99 | |

| The Dysfunctional Question | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolutely Positive | Positive | Neutral | Negative | Absolutely Negative | ||

| The Functional Question | Absolutely positive | Q | A | A | A | O |

| Positive | R | I | I | I | M | |

| Neutral | R | I | I | I | M | |

| Negative | R | I | I | I | M | |

| Absolutely negative | R | R | R | R | Q | |

| Research Questions/Hypotheses | Null and Alternative Statistical Hypotheses | Investigated Research Parameters Corresponding to the Hypothesis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Innovations are a tool for developing the sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia | H0 | Innovations are not a tool for developing the sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia | i. | innovations |

| H1 | Innovations are a tool for developing the sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia | ||||

| H2 | Small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia will implement innovations for compliance with standards (law) related to sustainable development | H0 | Small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia will not implement innovations for compliance with standards (law) related to sustainable development | xiv. | compliance with standards (laws) through innovations |

| H1 | Small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia will implement innovations for compliance with standards (law) related to sustainable development | ||||

| H3 | Small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia encounter various barriers when introducing innovations as a tool for sustainable development | H0 | Small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia do not encounter various barriers when introducing innovations as a tool for sustainable development | parameters identified by the Kano model as opposite requirements | |

| H1 | Small and medium-sized enterprises in Slovakia encounter various barriers when introducing innovations as a tool for sustainable development | ||||

| Properties n = 217 | A | I | M | O | Q | R | Category Requirement | Total Strength | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplicity | Multiplicity | Multiplicity | Multiplicity | Multiplicity | Multiplicity | |||||||||||

| Absolute | Relative | Absolute | Relative | Absolute | Relative | Absolute | Relative | Absolute | Relative | Absolute | Relative | |||||

| Perception of innovation as tools sustainable | innovations | 86 | 39.63 | 64 | 29.49 | 10 | 4.61 | 28 | 12.90 | 14 | 6.45 | 15 | 6.91 | A | 57.14 | 0.00384 |

| ecological innovations | 7 | 3.23 | 99 | 45.62 | 6 | 2.76 | 0 | 0.00 | 16 | 7.37 | 89 | 41.01 | I | 5.99 | 0.00552 | |

| the importance of innovations for the company’s strategy | 10 | 4.61 | 129 | 59.45 | 14 | 6.45 | 24 | 11.06 | 2 | 0.92 | 38 | 17.51 | I | 22.12 | 0.00576 | |

| implementation of innovations | 18 | 8.29 | 61 | 28.11 | 127 | 58.53 | 8 | 3.69 | 3 | 1.38 | 0 | 0.00 | M | 70.51 | 0.00608 | |

| product innovation | 72 | 33.18 | 59 | 27.19 | 13 | 5.99 | 3 | 1.38 | 0 | 0.00 | 70 | 32.26 | A | 40.55 | 0.00419 | |

| process innovations | 34 | 15.67 | 76 | 35.02 | 10 | 4.61 | 4 | 1.84 | 4 | 1.84 | 89 | 41.01 | R | 22.12 | 0.00461 | |

| increasing labor productivity through innovation | 14 | 6.45 | 111 | 51.15 | 2 | 0.92 | 0 | 0.00 | 14 | 6.45 | 76 | 35.02 | I | 7.37 | 0.00564 | |

| increase in turnover through innovation | 6 | 2.76 | 175 | 80.65 | 8 | 3.69 | 6 | 2.76 | 0 | 0.00 | 22 | 10.14 | I | 9.22 | 0.00836 | |

| reducing environmental impacts through innovation | 36 | 16.59 | 153 | 70.51 | 6 | 2.76 | 6 | 2.76 | 2 | 0.92 | 14 | 6.45 | I | 22.12 | 0.00715 | |

| growth of competitiveness through innovation | 14 | 6.45 | 173 | 79.72 | 10 | 4.61 | 4 | 1.84 | 0 | 0.00 | 16 | 7.37 | I | 12.90 | 0.00822 | |

| increasing the company’s market share through innovation | 16 | 7.37 | 165 | 76.04 | 8 | 3.69 | 6 | 2.76 | 0 | 0.00 | 22 | 10.14 | I | 13.82 | 0.00777 | |

| increasing profits through innovation | 16 | 7.37 | 165 | 76.04 | 10 | 4.61 | 4 | 1.84 | 0 | 0.00 | 22 | 10.14 | I | 13.82 | 0.00777 | |

| cost reduction through innovation | 100 | 46.08 | 81 | 37.33 | 8 | 3.69 | 6 | 2.76 | 0 | 0.00 | 22 | 10.14 | A | 52.53 | 0.00527 | |

| compliance with standards (laws) through innovations | 11 | 5.07 | 74 | 34.10 | 85 | 39.17 | 1 | 0.46 | 0 | 0.00 | 46 | 21.20 | M | 44.70 | 0.00460 | |

| high costs for the implementation of innovations | 51 | 23.50 | 66 | 30.41 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 26 | 11.98 | 74 | 34.10 | R | 23.50 | 0.00396 | |

| profitability of investments in innovations and the innovation process | 35 | 16.13 | 79 | 36.41 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 14 | 6.45 | 89 | 41.01 | R | 16.13 | 0.00480 | |

| innovation risk | 32 | 14.75 | 74 | 34.10 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 18 | 8.29 | 93 | 42.86 | R | 14.75 | 0.00477 | |

| experience and know-how with the implementation of innovations and the innovation process | 19 | 8.76 | 85 | 39.17 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 1.84 | 109 | 50.23 | R | 8.76 | 0.00589 | |

| workforce in the implementation of innovations | 29 | 13.36 | 85 | 39.17 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 2.76 | 97 | 44.70 | R | 13.36 | 0.00537 | |

| cooperation in the implementation of innovations | 29 | 13.36 | 80 | 36.87 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 12 | 5.53 | 96 | 44.24 | R | 13.36 | 0.00511 | |

| information for the implementation of innovations and their support | 21 | 9.68 | 100 | 46.08 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 2.76 | 90 | 41.47 | I | 9.68 | 0.00566 | |

| financial means for innovation and the innovation process | 55 | 25.35 | 68 | 31.34 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 18 | 8.29 | 76 | 35.02 | R | 25.35 | 0.00420 | |

| bureaucracy | 45 | 20.74 | 90 | 41.47 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 12 | 5.53 | 70 | 32.26 | I | 20.74 | 0.00467 | |

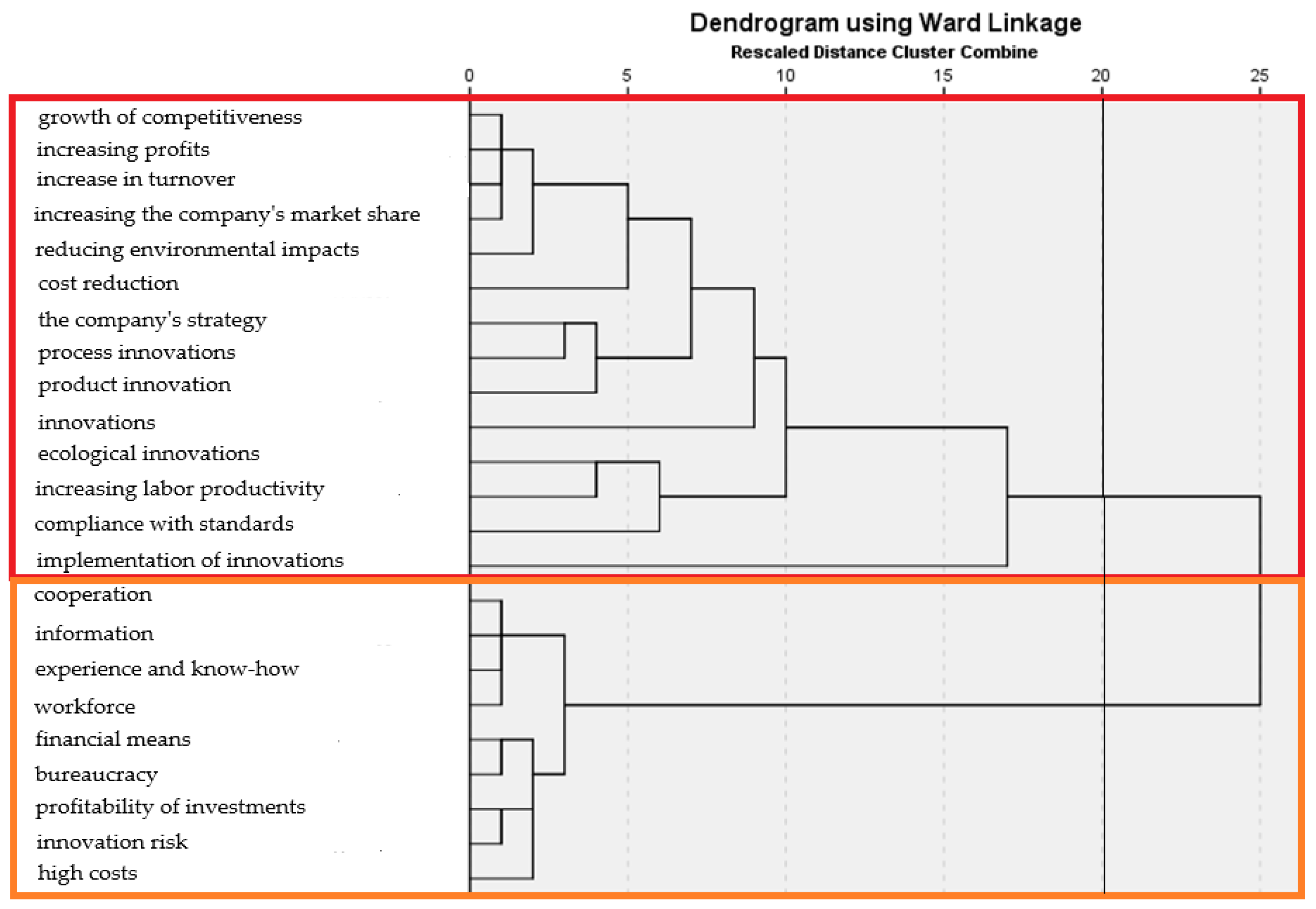

| Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 |

|---|---|

| innovations | high costs for the implementation of innovations |

| ecological innovations | profitability of investments in innovations and the innovation process |

| the importance of innovations for the company’s strategy | innovation risk |

| implementation of innovations | experience and know-how with the implementation of innovations and the innovation process |

| product innovation | workforce in the implementation of innovations |

| process innovations | cooperation in the implementation of innovations |

| increasing labor productivity through innovation | information for the implementation of innovations and their support |

| increase in turnover through innovation | financial means for innovation and the innovation process |

| reducing environmental impacts through innovation | bureaucracy |

| growth of competitiveness through innovation | |

| increasing the company’s market share through innovation | |

| increasing profits through innovation | |

| cost reduction through innovation | |

| compliance with standards (laws) through innovations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loučanová, E.; Nosáľová, M.; Olšiaková, M.; Štofková, Z.; Dumiter, F.C.; Nicoară, Ș.A.; Boiță, M. Innovation as a Tool for Sustainable Development in Small and Medium Size Enterprises in Slovakia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115393

Loučanová E, Nosáľová M, Olšiaková M, Štofková Z, Dumiter FC, Nicoară ȘA, Boiță M. Innovation as a Tool for Sustainable Development in Small and Medium Size Enterprises in Slovakia. Sustainability. 2023; 15(21):15393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115393

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoučanová, Erika, Martina Nosáľová, Miriam Olšiaková, Zuzana Štofková, Florin Cornel Dumiter, Ștefania Amalia Nicoară, and Marius Boiță. 2023. "Innovation as a Tool for Sustainable Development in Small and Medium Size Enterprises in Slovakia" Sustainability 15, no. 21: 15393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115393

APA StyleLoučanová, E., Nosáľová, M., Olšiaková, M., Štofková, Z., Dumiter, F. C., Nicoară, Ș. A., & Boiță, M. (2023). Innovation as a Tool for Sustainable Development in Small and Medium Size Enterprises in Slovakia. Sustainability, 15(21), 15393. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115393