Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on Impulse Buying Intention: Exploring the Moderating Influence of Social Media Advertising

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Supporting Theory

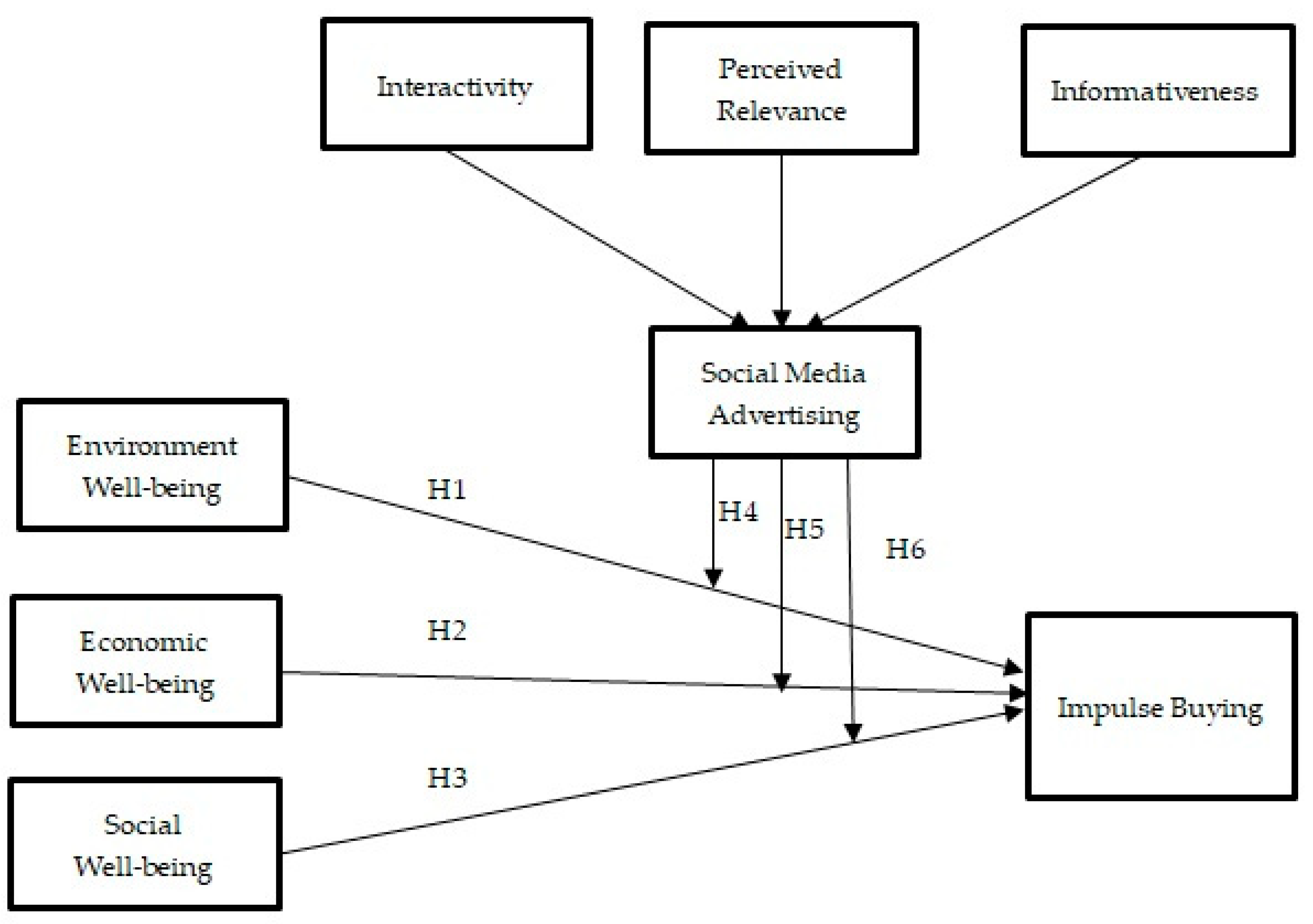

2.2. Sustainable CSR Practices and Impulsive Buying Intention

2.3. Moderating Role of Social Media Advertising between CSR and Impulsive Buying

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

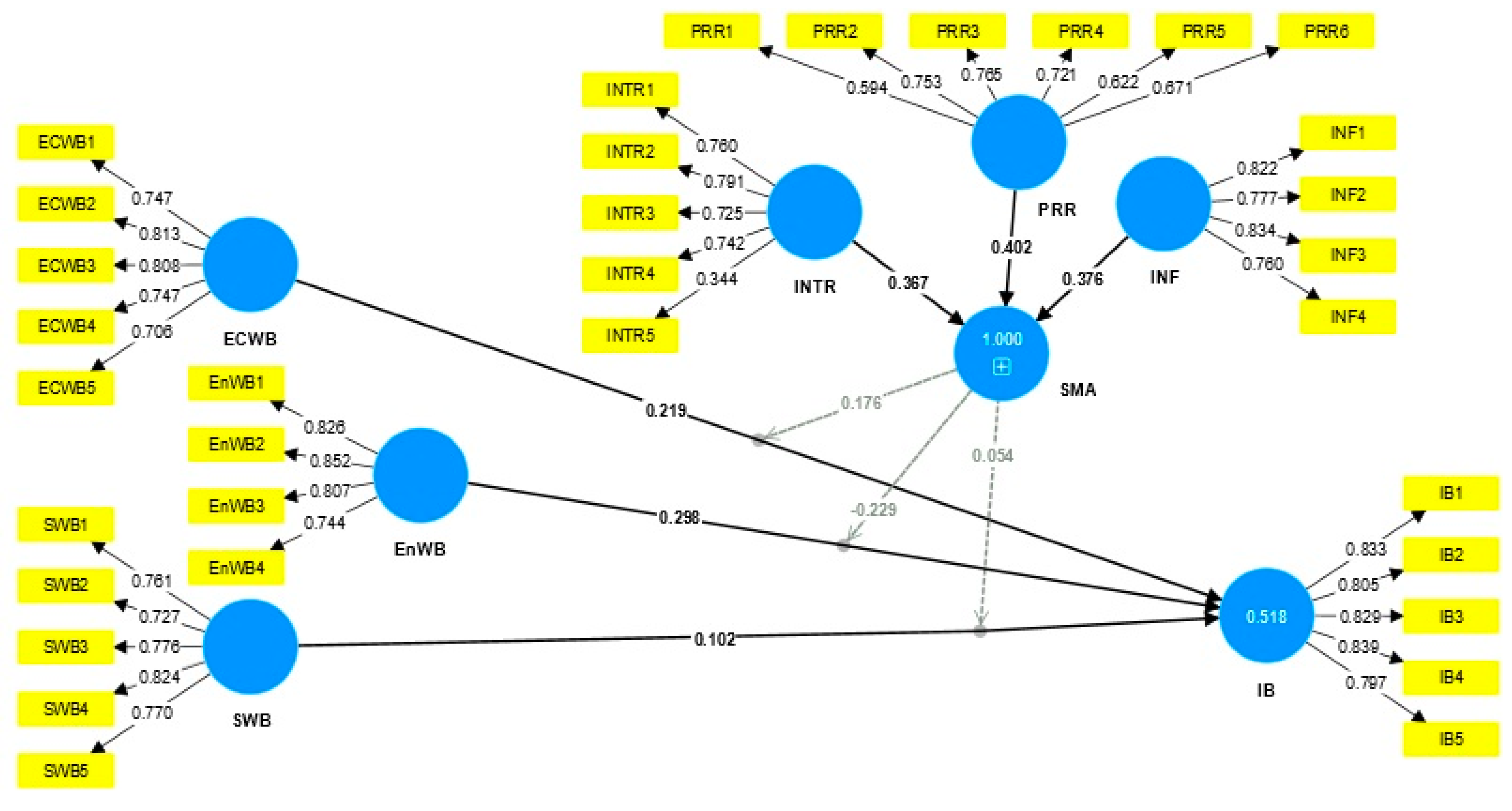

4.1. Measurement Model Analysis

4.2. Discriminant Validity

4.3. Assessment of Second-Order Construct

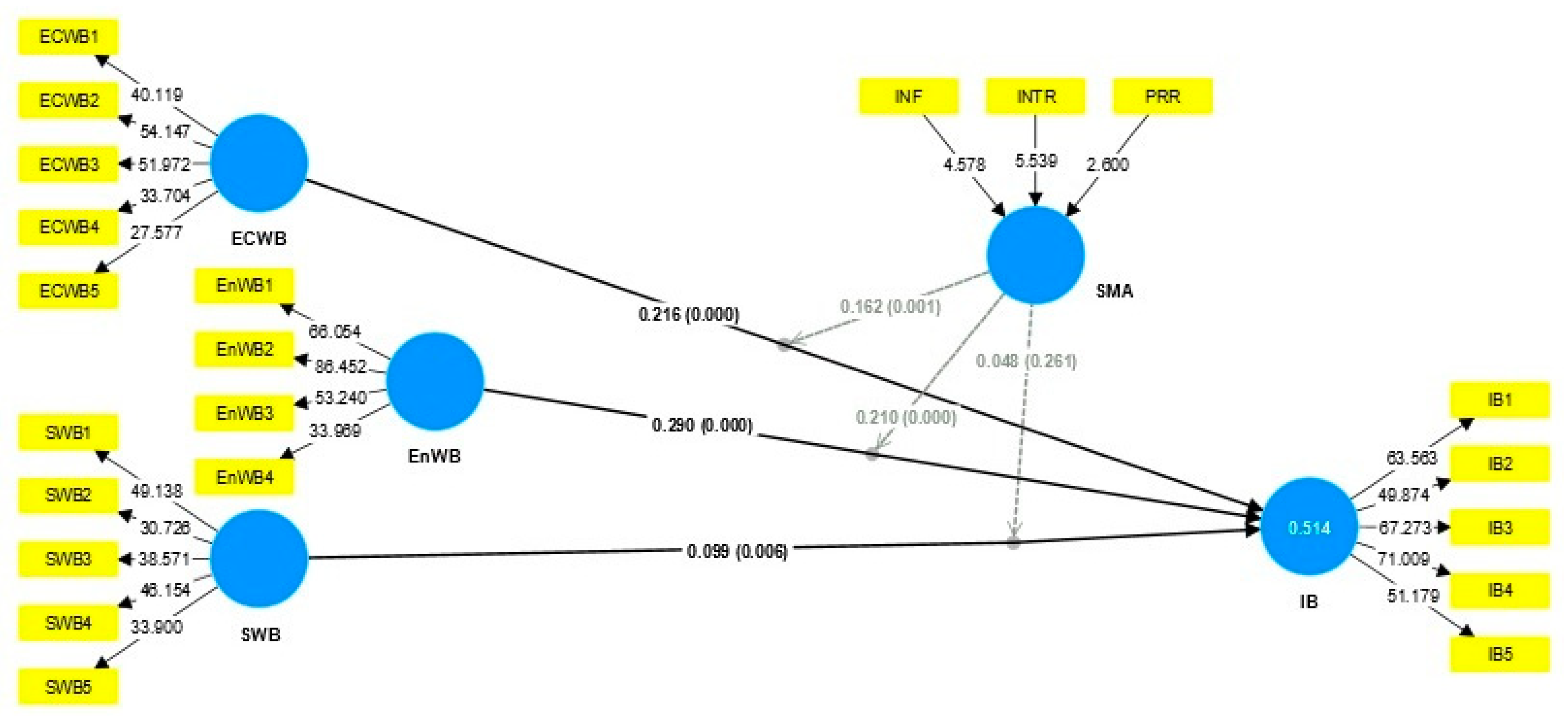

4.4. Structural Equation Model Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Theoretical Implications

8. Managerial Implications

9. Limitations and Future Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Environment Well-being

- EnWB1: I purchase the product of that firm, which is environment-friendly.

- EnWB2: I buy the product of that firm, which involves the green environment.

- EnWB3: I like to buy the product of that company, which tries to recycle its waste properly.

- EnWB4: If I have some choices in the shopping mall to buy a product than I prefer to buy from that company, which involves keeping the environment clean.

- Social Well-being

- SWB1: I purchase the product of that company, which donates to charity for society.

- SWB2: I do not buy the products of those companies that use child labor.

- SWB3: I do not buy the products of those companies that are socially irresponsible.

- SWB4: A firm, which promotes education, is my first choice to buying its product.

- Economic Well-being

- EcWB1: I buy the products of those companies, which are involved in the betterment of the living standard of their stakeholders.

- EcWB2: I prefer the firm that cares about its stakeholders for profit.

- EcWB3: I prefer the product of a firm that financially supports its employees.

- EcWB4: I believe companies that undertake CSR strategies offer better-quality products and services.

- EcWB5: It makes sense to always choose the products of that firm, which involves economic well-being actions, even if other products are better than them.

- Impulse buying

- IB1: When I go shopping, I buy things that I had not intended to buy.

- IB2: I often buy things spontaneously.

- IB3: I often buy things without thinking properly.

- IB4: Sometimes, I like buying things on the spur of the moment (sudden moment).

- IB5: When suddenly I see the product of a firm, which is involved in environmental initiatives, I purchase it at that time without thinking deeply.

- Perceived Relevance

- PRR1: Social media advertising is relevant to me.

- PRR2: Social media advertising is important to me.

- PRR3: Social media advertising means a lot to me.

- PRR: I think social media advertising fits my interests.

- PRR5: I think social media advertising fits with my preferences.

- PRR6: Overall, I think social media advertising fits me.

- Interactivity

- INTER1: Social media advertising is effective in gathering customers’ feedback.

- INTER2: Social media advertising makes me feel like it wants to listen to its customers.

- INTER3: Social media advertising encourages customers to offer feedback.

- INTER4: Social media advertising gives customers the opportunity to talk back.

- INTER5: Social media advertising facilitates two-way communication between the customers and the firms.

- Informativeness

- INF1: Social media advertising is a good source of product information and supplies relevant product information.

- INF2: Social media advertising provides timely information.

- INF3: Social media advertising is a good source of up-to-date product information.

- INF4: Social media advertising is a convenient source of product information.

- INF5: Social media advertising supplies complete product information.

References

- Moes, A.; Fransen, M.; Verhagen, T.; Fennis, B. A good reason to buy: Justification drives the effect of advertising frames on impulsive socially responsible buying. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 2260–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, N.; Jafari-Sadeghi, V. Corporate social responsibility and green behaviour: Towards sustainable food-business development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassani, A.A.; Yousaf, Z.; Radulescu, M.; Haffar, M. Environmental performance through environmental resources conservation efforts: Does corporate social responsibility authenticity act as mediator. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, K.; Jianjun, Z.; Ali, S.; Ageli, M.M. Eco-advertising and ban-on-plastic: The influence of CSR green practices on green impulse behavior. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The process model of corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication: CSR communication and its relationship with consumers’ CSR knowledge, trust, and corporate reputation perception. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 1143–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Jiang, X.; Qureshi, M.A.; Akbar, M. Does corporate environmental investment impede financial performance of Chinese enterprises? The moderating role of financial constraints. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 58007–58017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, K.; Jianjun, Z.; Zameer, H.; Iqbal, S. Understanding the influence of corporate social responsibility practices on impulse buying. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.A.; Tehseen, S. Role of decision intelligence in strategic business planning. In Decision Intelligence Analytics and the Implementation of Strategic Business Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Vázquez-Burguete, J.L.; García-Miguélez, M.P.; Lanero-Carrizo, A. Internal corporate social responsibility for sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlutova, I.; Fomins, A.; Spilbergs, A.; Atstaja, D.; Brizga, J. Opportunities to increase financial well-being by investing in environmental, social and governance with respect to improving financial literacy under COVID-19: The case of Latvia. Sustainability 2021, 14, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Rosati, F.; Chai, H.; Feng, T. Market orientation practices enhancing corporate environmental performance via knowledge creation: Does environmental management system implementation matter? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 1899–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Farrukh, M.; Iqbal, M.K.; Farhan, M.; Wu, Y. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior: The role of organizational pride and employee engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazman, V.D. A new criterion for the ESG model. Green Low-Carbon Econ. 2023, 1, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.A.; Khan, Z. Corporate social responsibility: A pathway to sustainable competitive advantage. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E. A review of corporate social responsibility in developed and developing nations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Abraham, R.; Yadav, J.; Agrawal, A.K.; Kolar, P. Linking CSR and organizational performance: The intervening role of sustainability risk management and organizational reputation. Soc. Responsib. J. 2023, 19, 1830–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, N.T.; Nga, P.T.; Thuan TT, H. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the impacts on impulse buying behavior: A literature review. Ho Chi Minh City Open Univ. J. Sci.-Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. Consumer perceived corporate social responsibility and electronic word of mouth in social media: Mediating role of consumer–company identification and moderating role of user-generated content. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, B.P.; Shiva, A.; Tyagi, V. How Investors’ Financial Well-being Influences Enterprises and Individual’s Psychological Fitness? Moderating Role of Experience under Uncertainty. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Chishti, M.F.; Durrani, M.K.; Bashir, R.; Safdar, S.; Hussain, R.T. The Corporate Social Responsibility and Its Impact on Financial Performance: A Case of Developing Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, K.; Jianjun, Z.; Ullah, S. Relationship of Corporate Social Responsibility and Impulse Buying: Role of Corporate Reputation and Consumer Company Identification. Int. J. Manag. Res. Emerg. Sci. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, A.; Mardikaningsih, R. The Potential of social media as a Means of Online Business Promotion. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. (JOS3) 2022, 2, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, K.; Dunnan, L.; Gul, R.F.; Shehzad, M.U.; Gillani, S.H.M.; Awan, F.H. Role of social media marketing activities in influencing customer intentions: A perspective of a new emerging era. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qader, K.S.; Hamza, P.A.; Othman, R.N.; Anwer, S.A.; Hamad, H.A.; Gardi, B.; Ibrahim, H.K. Analyzing different types of advertising and its influence on customer choice. Int. J. Humanit. Educ. Dev. (IJHED) 2022, 4, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker Qureshi, P.A.; Murtaza, F.; Kazi, A.G. The impact of social media on impulse buying behaviour in Hyderabad Sindh Pakistan. Int. J. Entrep. Res. 2019, 2, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Khan, S.; Rehman, S.; Naz, S.; Haider, S.A.; Kayani, U.N. Ameliorating sustainable business performance through green constructs: A case of manufacturing industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvaj, I.; Drbúl, M.; Bůžek, M. Sustainability in Small and Medium Enterprises, Sustainable Development in the Slovak Republic, and Sustainability and Quality Management in Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, P.R.; Pitt, L.F.; Plangger, K.; Shapiro, D. Marketing meets Web 2.0, social media, and creative consumers: Implications for international marketing strategy. Bus. Horiz. 2012, 55, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.; Kabir, G. Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) of Package Deliveries: Sustainable Decision-Making for the Academic Institutions. Green Low-Carbon Econ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Lin, C.P. Understanding the effect of social media marketing activities: The mediation of social identification, perceived value, and satisfaction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 140, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, S.; Bharathi, K. Role of social media influence on customer’s impulsive buying behavior towards apparel. Int. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2018, 7, 903–908. [Google Scholar]

- Shaker, K.; Mufti, M.N.; Zahid, M.Z. Impulse buying behavior and the role of social media: A case study of Faisalabad. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Res. 2017, 6, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, B.; Ling, P.; Yazdanifard, R. What internal and external factors influence impulsive what internal and external factors influence. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2015, 15, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nayal, P.; Pandey, N.; Paul, J. COVID-19 pandemic and consumer-employee-organization wellbeing: A dynamic capability theory approach. J. Consum. Aff. 2022, 56, 359–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, Z.N. Marketing strategy: The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Awareness. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2022, 6, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on attitude-behavior relationships: A natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Zehou, S.; Raza, S.A.; Qureshi, M.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. Impact of CSR and environmental triggers on employee green behavior: The mediating effect of employee well-being. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2225–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Bento, P.; Akbar, A. Does CSR influence firm performance indicators? Evidence from Chinese pharmaceutical enterprises. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Foord, D.; Frecè, J.; Hillebrand, K.; Kissling-Näf, I.; Meili, R.; Stucki, T. Corporate Sustainability. In Sustainable Business: Managing the Challenges of the 21st Century; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sachitra, V.; Konara, S. Role of Interior and Exterior Stores Visual Merchandising on Consumers’ Impulsive Buying Behaviour: Reference to Apparel Retail Stores in Sri Lanka. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2023, 40, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chtioui, R.; Berraies, S.; Dhaou, A. Perceived corporate social responsibility and knowledge sharing: Mediating roles of employees’ eudaimonic and hedonic well-being. Soc. Responsib. J. 2023, 19, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. Environmental Regulation and Public Environmental Concerns in China: A New Insight from the Difference in Difference Approach. Green Low-Carbon Econ. 2023, 1, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawary SI, S.; Al-Fassed, K.J. The impact of social media marketing on building brand loyalty through customer engagement in Jordan. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2022, 28, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, I.; Kılıç, H.Y.; Aralık, E. Impulsive Buying as a Response to COVID-19-Related Negative Psychological States. In Perspectives on Stress and Wellness Management in Times of Crisis; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 104–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rustamzade, G.; Aghayeva, K. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in Azerbaijan. TURAN Strat. Arastirmalar Merk. 2023, 15, 623–635. [Google Scholar]

- Shoham, A.; Gavish, Y.; Segev, S. A cross-cultural analysis of impulsive and compulsive buying behaviors among Israeli and US consumers: The influence of personal traits and cultural values. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2015, 27, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pütz, L.; Schell, S.; Werner, A. Openness to knowledge: Does corporate social responsibility mediate the relationship between familiness and absorptive capacity. Small Bus. Econ. 2023, 60, 1449–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.A.; Rehman, A.; Tehseen, S. Impact of Online and Social Media Platforms in Organizing the Events: A Case Study on Coke Fest and Pakistan Super League. In Digital Transformation and Innovation in Tourism Events; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, M.; Basha, A.M. The Influence of Social Media Platform on Purchase Intention and Consumer Decision-Making: Post COVID-19. Recent Adv. Commer. Manag. 2022, 1, 222–232. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, H. A Way Forward through Customer, Situational and Demographics Determinants Affecting Impulsive Buying Behavior: An Empirical Research. 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10579/22214 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I. Corporate social responsibility and brand advocacy among consumers: The mediating role of brand trust. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, W.; Poulova, P.; Haider, S.A.; Sham, R.B. Impact of internet usage on consumer impulsive buying behavior of agriculture products: Moderating role of personality traits and emotional intelligence. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 951103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghese, S.; Agrawal, M. Impact of social media on Consumer Buying Behavior. Saudi J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2021, 6, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhi, K.; Chen, Y. How active and passive social media use affects impulse buying in Chinese college students? The roles of emotional responses, gender, materialism and self-control. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1011337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Hung-Baesecke, C.J.F.; Chen, Y.R.R. Social media influencer effects on CSR communication: The role of influencer leadership in opinion and taste. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2021, 23294884211035112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Strategic attributions of corporate social responsibility and environmental management: The business case for doing well by doing good! Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, K.G.; Harun, A.; Abdulmaged, B.; Melhem, I.; Mechman, A.; Mohammed, A. The influence of corporate social responsibility communication (CSR) on customer satisfaction towards hypermarkets in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia. Resmilitaris 2023, 13, 3892–3907. [Google Scholar]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, S. “I buy green products for my benefits or yours”: Understanding consumers’ intention to purchase green products. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 1721–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Kim, H.G. Can social media marketing improve customer relationship capabilities and firm performance? Dynamic capability perspective. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 39, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantulga, U.; Dashrentsen, D. Factors Influence Impulsive Buying Behavior. Humanit. Univ. Res. Pap. Manag. 2023, 24, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Iqbal, S.; Asghar, W.; Haider, S.A. Corporate social responsibility for competitive advantage in project management: Evidence from multinational fast-food companies in Pakistan. J. Bus. Soc. Rev. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 6, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. The Influence of User Sharing Behavior on Consumer Purchasing Behavior in social media. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2023, 13, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodoo, N.A.; Wu, L. Exploring the anteceding impact of personalised social media advertising on online impulse buying tendency. Internet Mark. Advert. 2019, 13, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, K.; Basak, S. Role of Social Media in CSR Communication: A Study from Bangladesh Perspective. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 9, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apuke, O.D. Quantitative research methods: A synopsis approach. Kuwait Chapter Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 33, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangleburg, T.F.; Doney, P.M.; Bristol, T. Shopping with friends and teens’ susceptibility to peer influence. J. Retail. 2004, 80, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Borges, A.P. Corporate social responsibility and its impact in consumer decision-making. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Kim, E.Y.; Funches, V.M.; Foxx, W. Apparel product attributes, web browsing, and e-impulse buying on shopping websites. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Chan, J.; Tan, B.C.; Chua, W.S. Effects of interactivity on website involvement and purchase intention. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2010, 11, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Huang, L.; Dou, W. Social factors in user perceptions and responses to advertising in online social networking communities. J. Interact. Advert. 2009, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, K.; Bright, L.F.; Gangadharbatla, H. Facebook versus television: Advertising value perceptions among females. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2012, 6, 164–179. [Google Scholar]

- Tehseen, S.; Ramayah, T.; Sajilan, S. Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. J. Manag. Sci. 2017, 4, 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.J.; Van Witteloostuijn, A.; Eden, L. Common method variance in international business research. In Research Methods in International Business; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 385–398. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Sinkovics, N.; Sinkovics, R.R. A perspective on using partial least squares structural equation modelling in data articles. Data Brief 2023, 48, 109074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S.; Ray, S. Evaluation of formative measurement models. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Falcó, J.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Zaragoza-Sáez, P.; Sánchez-García, E. The effect of knowledge management on sustainable performance: Evidence from the Spanish wine industry. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Pick, M.; Liengaard, B.D.; Radomir, L.; Ringle, C.M. Progress in partial least squares structural equation modelling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Hamid, M.R.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M.M. Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar]

- Yusoff, A.S.M.; Peng, F.S.; Abd Razak, F.Z.; Mustafa, W.A. Discriminant validity assessment of religious teacher acceptance: The use of HTMT criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1529, 042045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Yan, R.-N.; Eckman, M. Moderating effects of situational characteristics on impulse buying. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, A.; Abe, M.; Shannon, R. The dark side of social media: Content effects on the relationship between materialism and consumption behaviors. Front. Psychol 2022, 13, 870614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahath, A.; Omar, N.A.; Ali, M.H.; Tseng, M.L.; Yazid, Z. Exploring food waste during the COVD-19 pandemic among malaysian consumers: The effect of social media, neuroticism, and impulse buying on food waste. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.U.; Qiu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Shahzad, M. The impact of social media celebrities’ posts and contextual interactions on impulse buying in social commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 115, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyani, V.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Hidayanto, A.N.; Sandhyaduhita, P.I.; Hsiao, B. Exploring the psychological mechanisms from personalized advertisements to urge to buy impulsively on social media. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zheng, Y. An Analysis of How Video Advertising Factors Influence Consumers’ Impulse Purchase Intentions. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Aragoncillo, L.; Orus, C. Impulse buying behaviour: An online-offline comparative and the impact of social media. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2018, 22, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, R.M.; Rashid, S. Impact of Digital Marketing on Impulsive Buying Behavior. J. Mark. Strateg. 2023, 5, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Topor, D.I.; Maican, S.Ș.; Paștiu, C.A.; Pugna, I.B.; Solovăstru, M.Ș. Using CSR communication through social media for developing long-term customer relationships. The case of Romanian consumers. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. Res. 2022, 56, 255–272. [Google Scholar]

- Nuseir, M.T. The extent of the influences of social media in creating ‘impulse buying’ tendencies. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2020, 21, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Categories | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 388 | 56.6 |

| Male | 298 | 43.4 | |

| Age | 20–30 | 328 | 47.8 |

| 31–40 | 194 | 28.3 | |

| 41–50 | 156 | 22.7 | |

| >50 | 8 | 1.2 | |

| Education | Bachelor’s | 247 | 36.0 |

| Master’s | 201 | 29.3 | |

| MS/MPhil | 188 | 27.4 | |

| PhD | 15 | 2.2 | |

| Any other | 35 | 5.1 | |

| Work Experience | <3 | 69 | 10.1 |

| 3–6 | 165 | 24.1 | |

| 7–10 | 266 | 38.8 | |

| >10 | 186 | 27.1 |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading | α | CR (rho_a) | CR (rho_c) | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Well-being | 0.825 | 0.838 | 0.876 | 0.586 | ||

| ECWB1 | 0.747 | |||||

| ECWB2 | 0.813 | |||||

| ECWB3 | 0.808 | |||||

| ECWB4 | 0.747 | |||||

| ECWB5 | 0.706 | |||||

| Environment Well-being | 0.822 | 0.828 | 0.882 | 0.653 | ||

| EnWB1 | 0.826 | |||||

| EnWB2 | 0.852 | |||||

| EnWB3 | 0.807 | |||||

| EnWB4 | 0.744 | |||||

| Social Well-being | 0.839 | 0.885 | 0.881 | 0.597 | ||

| SWB1 | 0.761 | |||||

| SWB2 | 0.727 | |||||

| SWB3 | 0.776 | |||||

| SWB4 | 0.824 | |||||

| SWB5 | 0.770 | |||||

| Impulse Buying | 0.879 | 0.879 | 0.912 | 0.674 | ||

| IP1 | 0.833 | |||||

| IP2 | 0.805 | |||||

| IP3 | 0.829 | |||||

| IP4 | 0.839 | |||||

| IP5 | 0.797 | |||||

| Social Media Advertising | ||||||

| Interactivity | 0.716 | 0.767 | 0.813 | 0.519 | ||

| INTR1 | 0.760 | |||||

| INTR2 | 0.791 | |||||

| INTR3 | 0.725 | |||||

| INTR4 | 0.742 | |||||

| INTR5 | 0.344 | |||||

| Perceived Relevance | 0.779 | 0.782 | 0.844 | 0.527 | ||

| PRR1 | 0.594 | |||||

| PRR2 | 0.753 | |||||

| PRR3 | 0.765 | |||||

| PRR4 | 0.721 | |||||

| PRR5 | 0.622 | |||||

| PRR6 | 0.671 | |||||

| Informativeness | 0.810 | 0.812 | 0.876 | 0.638 | ||

| INF1 | 0.822 | |||||

| INF2 | 0.777 | |||||

| INF3 | 0.834 | |||||

| INF4 | 0.760 | |||||

| Constructs | Economic Well-Being | Environment Well-Being | Impulse Buying | Social Well-Being |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Well-being | ||||

| Environment Well-being | 0.694 | |||

| Impulse Buying | 0.563 | 0.765 | ||

| Social Well-being | 0.659 | 0.632 | 0.502 |

| Relationship among Constructs | β | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | T Values | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INF -> SMA | 0.370 | 0.370 | 0.011 | 33.295 | 0.000 |

| INTR -> SMA | 0.372 | 0.372 | 0.012 | 31.449 | 0.000 |

| PRR -> SMA | 0.402 | 0.402 | 0.012 | 32.864 | 0.000 |

| Constructs | R-Square | R-Square Adjusted | Q2 Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impulse Buying | 0.514 | 0.509 | 0.490 |

| Hypotheses | Relationship among Constructs | β | Sample Mean | S.D. | t Values | f Square Values | p Values | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | ||||||||

| H1 | EnWB -> IB | 0.290 | 0.290 | 0.057 | 5.067 | 0.044 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | ECWB -> IB | 0.216 | 0.215 | 0.046 | 4.659 | 0.067 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | SWB -> IB | 0.099 | 0.102 | 0.036 | 2.745 | 0.012 | 0.006 | Supported |

| Indirect Moderating Effect | ||||||||

| H4 | SMA × EnWB -> IB | 0.210 | 0.210 | 0.053 | 3.969 | 0.053 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5 | SMA × ECWB -> IB | 0.162 | 0.160 | 0.047 | 3.408 | 0.034 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6 | SMA × SWB -> IB | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.043 | 1.123 | 0.003 | 0.261 | Not supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lyu, L.; Zhai, L.; Boukhris, M.; Akbar, A. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on Impulse Buying Intention: Exploring the Moderating Influence of Social Media Advertising. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316258

Lyu L, Zhai L, Boukhris M, Akbar A. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on Impulse Buying Intention: Exploring the Moderating Influence of Social Media Advertising. Sustainability. 2023; 15(23):16258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316258

Chicago/Turabian StyleLyu, Lingbo, Li Zhai, Mohamed Boukhris, and Ahsan Akbar. 2023. "Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on Impulse Buying Intention: Exploring the Moderating Influence of Social Media Advertising" Sustainability 15, no. 23: 16258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316258

APA StyleLyu, L., Zhai, L., Boukhris, M., & Akbar, A. (2023). Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on Impulse Buying Intention: Exploring the Moderating Influence of Social Media Advertising. Sustainability, 15(23), 16258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316258