Abstract

This study examines the role of equitable management in preventing sexual harassment in the workplace and a loss of productivity during periods of crisis due to natural or social disasters. A structured survey of 445 women from 76 companies in five regions of northern Peru and a structural equation analysis show that companies that implement equitable management can mitigate the adverse effects of social conflicts and natural disasters. These findings indicate that equitable management is inversely related to counterproductive behaviors (β = −0.259, p < 0.001), sexual harassment at work (β = −0.349, p < 0.001), and turnover intention (β = −0.527, p < 0.001) and is positively associated with organizational citizenship behaviors (β = 0.204, p < 0.001) and psychological empowerment (β = 0.240, p < 0.001). Social conflicts and natural disasters, on the other hand, increase workplace sexual harassment (β = 0.244, p = 0.027) and intention to quit (β = 0.252, p < 0.001) and have a considerable impact on the loss of work productivity (β = 0.662, p < 0.001). However, in companies with fairer and more equitable management, this impact is much smaller and mitigated by these good practices. This suggests that equitable management protects against and prevents sexual harassment at work. In addition, it acts as a mechanism that enhances organizational citizenship behaviors and attitudes in the workplace which remain even in adverse external environments. This is an effective tool and strategy for maintaining productivity and organizational resilience in difficult times.

1. Introduction

In the workplace, critical events such as health epidemics, social conflicts, and natural disasters present challenges that can be devastating to the survival of companies [1]. These challenges can manifest in forms such as significant productivity losses, increased turnover intention, and the emergence of disruptive behaviors, including workplace sexual harassment and other counterproductive behaviors. In response to these crises, many organizations may be tempted to scale back preventive measures against gender-based violence, focusing on the immediate survival of the business. While this strategy may seem pragmatic in the short term, evidence does not support its long-term effectiveness.

In November 2022, Peru began to experience a series of social conflicts that developed into a social crisis. Initially, a self-coup d’état was ordered by former President Pedro Castillo. Then, the population demanded changes in the political constitution, requested the resignation of President Dina Boluarte, and requested the release of Pedro Castillo from imprisonment [2]. Additionally, the arrival of Cyclone Yaku in March 2023 and the beginning of the “El Niño” phenomenon in June 2023 triggered extreme rains on the country’s coast [3,4].

In this complex and challenging context, the present research starts from the premise that maintaining and strengthening equitable and fair management during crises could be essential to ensuring a healthy and productive work environment. The central hypothesis proposes that labor management focused on fairness and respect could foster workplace citizenship and protect against sexual harassment and other emerging problems. Despite its bold nature, this hypothesis was tested, with the support of the Lima Chamber of Commerce (CCL), the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation (AECID), and the European Union, by examining the experiences of workers in northern Peru, a region that has faced intense natural disasters and recent social conflicts.

This pioneering research study raises fundamental questions. Could equitable and fair management, in times of adversity, not only prevent sexual harassment but also foster productive behaviors such as workplace civility and psychological empowerment? Could these practices mitigate adverse impacts on labor productivity during periods of social or natural crisis? This research study explores these questions to understand how equitable management could be an effective and sustainable prevention tool, particularly in crisis contexts. The emphasis on equity and fairness emerges not as a reactive response to adversity but as a strategic and ethical principle that can strengthen the resilience and integrity of an organization, as well as the safety and well-being of its workers, even in turbulent times.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Workplace Sexual Harassment

Workplace sexual harassment (WSH) is a severe problem affecting millions of women’s wholeness and well-being worldwide [5]. WSH refers to unwanted sexual advances, unwelcome requests for sexual favors, verbal or physical conduct or gestures of a sexual nature, or any other sexual behavior that may be offensive, humiliating, or intimidating in the work environment [6]. WSH can thus encompass a wide variety of behaviors and practices of a sexual nature, including unwanted sexual comments or propositions, jokes with sexual content, the display of images or posters that objectify women, physical contact, or sexual assault [7]. Evidence shows that women are significantly more likely to be victims, and perpetrators primarily tend to be colleagues, followed by supervisors/bosses and clients [8].

WSH has gained substantial visibility in the last two decades, driven by global movements such as #MeToo and Time’s Up and powerful regional initiatives like #NiUnaMenos in Latin America. While #MeToo and Time’s Up have predominantly resonated in high-income countries, #NiUnaMenos emerged as a compelling voice against gender-based violence in Latin America, shedding light on deeply entrenched societal issues. This emphasis on confronting gender violence is particularly relevant given the high prevalence of workplace sexual harassment worldwide, with a notably significant incidence in countries in the Americas [5]. The situation is particularly alarming in Peru, with about one in three female private-sector workers reporting sexual harassment in the past year [8,9]. The strength and resonance of movements like #NiUnaMenos highlight the urgency and relevance of addressing these challenges head on.

The consequences of sexual harassment at work are multiple and severe. Studies show that those who experience sexual harassment report less job satisfaction, psychological distress (including anxiety, anger, and depression), and physical stress [10]. In addition, economic hardship may result from a loss of employment when victims decide to leave their positions or are fired in retaliation for reporting. Organizations in which harassment is prevalent often face absenteeism, increased staff turnover, decreased work performance and productivity [8], increased legal expenses, and the deterioration of their public image [11], among other effects.

2.2. The Impact of Conflict and Disasters on WSH

No specific studies have examined the relationship between the prevention of sexual harassment in the workplace and the loss of productivity during periods of crisis. However, numerous studies have separately explored the relationship between sexual harassment in the workplace and productivity loss, as well as the influence of economic, social, and natural crises on labor productivity and gender-based violence more broadly. For example, it is known that sexual harassment in the workplace can have detrimental effects on employee morale, mental and physical health, and, ultimately, on labor productivity [8,10]. In addition, crises can generate an environment of uncertainty and stress, which can negatively affect work productivity [12]. In adverse situations, such as war conflicts, droughts, and health crises, levels of gender-based violence against women often increase significantly [13].

Indeed, natural disasters and social crises can exacerbate existing violence trends, including workplace sexual harassment [14,15]. Although the focus has been on gender-based violence and not specifically WSH, we can argue that there are similarities in power imbalances that can drive both which are often rooted in patriarchal social norms and unequal gender systems [16]. In times of disaster, social destabilization creates environments conducive to individuals feeling more inclined to exert power and control over others, and sexual harassment can be a means of doing so. In addition, studies have evidenced that critical health events, natural disasters, and social crises may increase the vulnerability of certain groups to gender-based violence [13,17,18,19]. This vulnerability could also extend to sexual harassment. For example, women and gender minorities, often discriminated against and marginalized in the workplace, maybe even more vulnerable to WSH during these crises [14]. This may be especially true if commonly available support systems, such as human resources departments or peer networks, are less accessible or affected by the crisis [20]. Finally, studies suggest that crises may decrease the visibility and reporting of gender-based violence [15]. This could also be the case for WSH. In a crisis, individuals may feel less able or willing to report due to factors that inhibit reporting, such as a fear of retaliation or a lack of resources for addressing reporting during a crisis.

2.3. Equitable Management to Prevent WSH

Organizational justice and equitable management are crucial concepts in the effective operation of any organization or workplace. Equitable management refers to corporate practices and policies that ensure equal treatment of all employees, regardless of gender, race, religion, age, or other protected categories. These practices focus on removing barriers to equal opportunity and ensuring a work environment in which all members feel valued and respected [21]. Organizational justice refers to employees’ perception of the fairness of an organization’s treatment decisions, practices, and procedures [22]. This is subdivided into three main components: distributive justice (the perception of fairness in outcomes, such as salary and promotions), procedural justice (the perception of fairness in the processes leading to these outcomes), and interactional justice (the degree of treatment with dignity and respect involved in interactions with superiors, peers, and subordinates).

In an organization, equitable management is not just about being “fair” in abstract terms. It is a tangible and effective strategy that directly addresses the roots and dynamics of workplace sexual harassment, creating a safer and more respectful work environment for all. In fact, fair and just management can play a vital role in preventing sexual harassment. Organizations that promote fairness and equity tend to have cultures that do not tolerate sexual harassment. This type of culture manifests through clear policies, an open line of communication for complaints, effective sanctions for harassers, and empathetic responses to victims. In addition, the perception of a fair and safe work environment can deter potential harassers, reducing the prevalence of harassment. Indeed, a recent study conducted among female workers in private companies in Lima, Peru, found that fair relational management (specifically from management personnel) is a strong predictor of low levels of sexual harassment in the workplace [8]. In the companies whose management was more equitable and fairer, the prevalence and costs associated with WSH were significantly lower than in companies with less fair management. Indeed, lost labor productivity, turnover intention, and counterproductive behaviors were significantly lower.

There is evidence of the deterrent action that a perception of justice has on WSH [23] and how the presence of sexual harassment decreases the perception of justice in an organization [24]. For many reasons, equitable management in the work environment can be an essential factor in preventing WSH. 1. It sets a clear precedent: Management based on principles of fairness and equity communicates behavioral expectations to all employees. This ensures that inappropriate behavior, including sexual harassment, is not tolerated. 2. It promotes mutual respect: Equity and fairness in management foster an environment in which everyone is valued and respected for their skills and contributions and not for gender, race, or other non-work-related factors. This culture of respect reduces the likelihood of inappropriate behavior. 3. It reduces power inequalities: One of the factors that facilitates sexual harassment is an imbalance of power. Equitable and fair management minimizes such imbalances by ensuring that all employees, regardless of their position, are treated fairly and without favoritism. 4. It increases awareness and education: Organizations that value fairness and equity often invest in training and awareness programs that educate employees about appropriate behaviors and the consequences of harassment. 5. It provides mechanisms for reporting and addressing inappropriate behavior: Fair management ensures that transparent and fair channels exist for reporting inappropriate behavior. This ensures that victims feel supported and perpetrators are held accountable. 6. It develops an inclusive culture: By promoting fairness, organizations foster an inclusive culture in which everyone feels valued and accepted. In such environments, behaviors that seek to marginalize or harm others, such as sexual harassment, are less likely to occur. 7. It reinforces responsibility and accountability: Equity and fairness in management mean no exceptions based on position, status, or favoritism. Everyone, from top management to entry-level employees, is equally responsible for maintaining a safe work environment.

2.4. The Proposed Conceptual Model

The work environment is a dynamic space that internal and external factors can influence. During social conflicts or natural disasters, latent or emerging challenges can be exacerbated in crisis contexts, affecting team cohesion and productivity. These crises can lead to counterproductive behaviors, such as sexual harassment in the workplace and turnover intention.

Several previous studies highlighted the importance of equitable leadership and management in promoting a healthy and productive work environment [22,25,26]. However, our study highlights the ability of equitable and fair management to act as a sort of “shield” against the adverse effects of external shocks. The inverse relationship between equitable management and behaviors such as sexual harassment and turnover intention underscores this point. Our study suggests that equitable and fair management acts directly and enhances proactive behaviors and attitudes, such as psychological empowerment [27] and workplace civic or organizational citizenship behaviors [28,29,30,31]. This could be because equity and fairness promote mutual respect among employees, generating a work environment in which everyone’s well-being is valued and protected [32].

During a social or natural disaster crisis, equitable management can buffer the effects that such crises would have on labor productivity and the prevalence of sexual harassment. Employees may feel anxious and insecure about their position and future during a crisis. If they think they are being treated fairly, they are more likely to maintain their level of productivity [33,34,35]. Fairness can also improve morale and commitment [36], leading to more significant discretionary effort (i.e., willingness to go beyond basic work expectations). In contrast, perceived unfair treatment can lead to low engagement, low performance, and increased counterproductive behaviors at work (e.g., intentionally damaging or waste company property or intentionally performing the duties of your position more slowly or incorrectly).

A key characteristic of successful companies is their ability to adapt and thrive in adverse situations. This resilience is not only related to financial or strategic capacity but also to the well-being and productivity of their workforce [37]. Equitable management emerges as a powerful tool for maintaining and enhancing productivity and organizational resilience in challenging times. It is posited that these proactive behaviors fostered by equitable management are highly resilient in times of crisis, which is conducive to productivity. Thus, it is clear that equitable practices are not simply “nice to have” but are essential to the health and resilience of a company, particularly in times of crisis. Adopting and maintaining these practices not only protects employees from harmful behaviors but also strengthens the structure and resilience of the entire organization.

A critical aspect of our conceptual model is the inclusion of supplementary variables, such as turnover intention, psychological empowerment, organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs), and counterproductive behaviors. While the primary focus of our research revolves around workplace sexual harassment, equitable management, labor productivity loss (LPL), and the impact of social conflicts and natural disasters, these additional variables play a crucial role in providing a more comprehensive understanding of the complex dynamics within the workplace during times of crisis. These supplementary variables were carefully considered due to their significant relevance to the study’s context. For instance, prior research established a strong connection between workplace sexual harassment and turnover intention [8], highlighting the need to explore these variables in conjunction. Moreover, equitable management has demonstrated relationships with psychological empowerment, organizational citizenship behaviors, and counterproductive behaviors [27,28,29,30,31]. By integrating these variables into our conceptual model, we aim to capture a holistic view of how equitable management and crisis impact various dimensions of productivity, well-being, and organizational behavior. This approach enriches our research and enables us to offer more comprehensive insights to both academic and practical audiences.

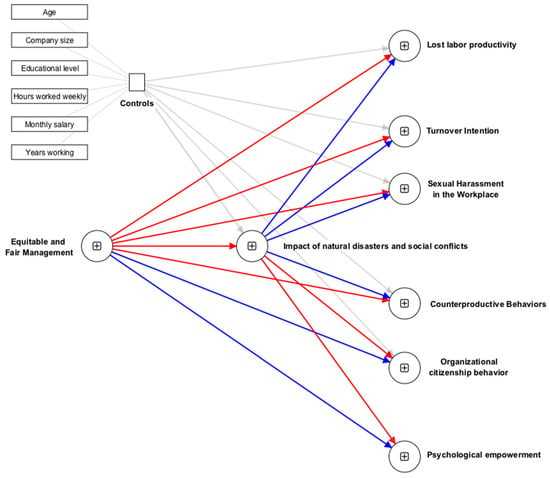

Figure 1 shows the proposed conceptual model from which the four primary research hypotheses are derived.

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual model. Note: Red lines (negative or inverse relationships), blue lines (positive or direct relationships), and grey lines control for the effects of possible confounding variables (ceteris paribus).

H1.

Companies implementing equitable management have lower incidences of sexual harassment, counterproductive behaviors, and intentions of labor desertion.

H2.

The implementation of equitable management in companies is directly related to positive attitudes and behaviors, such as labor civic behavior and the psychological empowerment of female workers.

H3.

Social conflicts and natural disasters increase sexual harassment at work and turnover intention and harm labor productivity.

H4.

Equitable and fair management demonstrates persistent and significant effects on the dependent variables through the mediation of social conflicts and natural disasters. When evaluating the indirect effects through mediation, these effects maintain their significance, providing evidence that equitable management acts as a protective factor in times of crisis.

To facilitate a comprehensive and rigorous analysis of these relationships, the four main research hypotheses are further disaggregated into nineteen specific statistical hypotheses. Additionally, to ensure greater control over potential confounding variables, this study includes control variables such as age, company size, educational level, hours worked per week, monthly salary, and employment tenure.

In short, our conceptual model assumes that social conflicts and natural disasters are expected to have a negative impact on labor productivity, psychological empowerment, and organizational citizenship behaviors while increasing workplace sexual harassment, turnover intention, and counterproductive behaviors [38]. These effects run contrary to what is anticipated with fair and equitable management, which tends to enhance labor productivity, psychological empowerment, and organizational citizenship behaviors while reducing workplace sexual harassment, turnover intention, and counterproductive behaviors. In our model, we posit that equitable and fair management is the independent variable, and its effects persist on the dependent variables through the mediation of social conflicts and natural disasters. It is highly likely that companies that have been investing in fair and equitable management during “normal” times will also be affected by crises, but their effects will be less pronounced. When assessing the indirect effects through mediation, these effects are expected to remain significant, suggesting that equitable and fair management continues to serve as a protective factor even in times of crisis.

3. Materials and Methods

The research was conducted in companies in the northern region of Peru during the first half of 2023, measuring events which occurred during the last 12 months. The selection was made because the north of the coastal region of Peru experiences frequent disturbances from natural disasters, particularly during extreme weather events such as the El Niño phenomenon [39] and the recent cyclone Yaku in March 2023. These phenomena provide ideal conditions for intense flooding and the proliferation of infectious and vector-borne diseases, such as dengue [40,41].

The extreme rainfall inherent to these climatic events often results in rivers and streams overflowing, causing significant damage to public and private infrastructure [42] and, in more severe circumstances, the loss of human lives. At the same time, post-flood stagnant waters provide breeding habitats for mosquito vectors of diseases such as dengue fever, yellow fever, and malaria. Natural disasters have a considerable effect on the business environment. Floods damage infrastructure, which can induce a temporary or total paralysis of business activities and, in turn, require substantial investments for reconstruction [43]. These catastrophes disrupt normal business operations due to the inaccessibility of employees and supplies and increase work absences due to illness, affecting productivity and raising health care costs. Specifically, the agricultural sector faces damage to crops and livestock, negatively influencing the food supply chain and raising prices.

On the other hand, from the second half of 2022 to mid-2023, the northern Peruvian region was also subjected to social and political conflicts which manifested in large-scale protests, road blockades, and high crime rates. This instability weakened investor confidence, inhibited business expansion, and disrupted day-to-day business. In the long term, it could hamper the region’s economic growth. Economic sectors are differentially affected by social conflicts. For example, in the tourism and hospitality sector, negative perceptions stemming from conflict and crime can deter potential tourists, reducing revenues and affecting hotel occupancy. The need for heightened security measures can also increase operating costs. In the transportation sector, road blockades interrupt the efficient flow of goods and services. Insecurity also increases operating costs and labor risks. In the services sector, suppliers that require direct customer access may need help with blockades. Establishments, such as restaurants, may face a reduction in customer traffic due to insecurity.

3.1. Participants

The field research was conducted from March to July 2023, focusing on experiences which occurred during the last 12 months. Through surveys, data were obtained from 445 women belonging to 76 companies in five regions of the Peruvian coast and highlands (Lambayeque, La Libertad, Tumbes, Piura, and Cajamarca) in a context of intense natural disasters resulting from the El Niño phenomenon and Cyclone Yaku, in addition to the presence of social and political conflicts, with significant economic consequences.

The mean age of the participants was 31.9 years (SD = 7.58). Of the respondents, 60.2% were single, while 32.8% were married or cohabiting, 5.8% were divorced, and 1.3% were widows. Of the women, 56.4% had children. Regarding income, 34.8% received a monthly income of less than USD 315, 44.2% received between USD 316 and USD 525, and 21.1% received more than USD 526. Regarding education, 12.4% had a secondary education, 30.4% had obtained a higher technical education, 15.8% had an incomplete university education, 36.9% had completed a university education, and 4.5% had completed postgraduate studies.

Regarding the type of employment contract, 36.1% of women had an indefinite-term contract, while the remainder had a temporary contract. Regarding work hours, 67.9% of the participants worked between 40 and 48 h, 15.5% worked more than 49 h, 11.5% worked between 20 and 29 h, and only 5.5% worked less than 20 h. In total, 80.8% had been employed in their current position for over a year. Regarding work activity, 3.3% worked in product manufacturing, storage, distribution, or other positions, 32.9% worked in administrative jobs, 8.1% identified themselves as management personnel, and 55.7% in worked sales, customer service or maintenance.

Regarding company size, 6.5% worked in small companies, 48.3% worked in medium-sized companies, and 45.2% worked in large companies. The participants worked in different sectors: accommodation and food service (15.5%), transportation and storage (25.8%), other services (42.0%), manufacturing (7.9%), construction (3.1%), information and communication (2.9%), commerce and vehicle repair (2.0%), and other (0.6%).

3.2. Instruments

Data collection was carried out through an anonymous and confidential structured questionnaire. The design of this questionnaire was conceived to facilitate the honesty and sincerity of the participants while guaranteeing the protection of their identity and the confidentiality of their responses. This methodology, therefore, promoted a safe environment for active and genuine participation in the research.

The study design and questionnaire were reviewed rigorously by the International Ethics Committee of the Universidad de San Martín de Porres (HHS IRB-00003251; FWA-00015320). This entity, which oversees the conduct of ethical research, validated the methodology and the data collection instrument to ensure that the fundamental ethical principles of the research, such as respect for human dignity, integrity, transparency, and protection of the study participants, were respected.

The data collection procedure involved distributing and collecting the questionnaires in a controlled and respectful environment. This ensured the participants’ confidentiality and the anonymity of their responses, as well as the right to not participate if they wished. Emphasis was placed on the importance of answering the questions honestly, and the option was provided to omit any questions that the participants considered too uncomfortable or invasive. At the end of the process, the questionnaires were collected and securely stored to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of the participants’ responses.

The questionnaire, in addition to demographic and occupational data, contained the variables described below.

3.2.1. Equitable and Fair Management

Equitable and fair management in the organizational environment is defined as an administrative approach that emphasizes the importance of treating all members of an organization with dignity and respect and without favoritism. This management style is based on principles of equity and fairness, recognizing and valuing each employee’s contribution and ensuring an appropriate distribution of rewards and responsibilities. In addition, it seeks to foster an environment of trust in which employees believe the organization will support them in adverse situations and will not take advantage of their vulnerabilities. Additionally, under this approach, leaders demonstrate a commitment to fairness, avoiding abusive or authoritarian behavior and showing genuine concern for the well-being and development of their team. This style of management promotes a work environment in which trust, respect, and fairness prevail, boosting employee commitment and productivity. Equitable and fair management was evaluated using two different but complementary scales. The first, a 10-item reflective scale, measures the frequency with which management behaviors based on fairness, respect, and inclusion are manifested. Designed by Vara-Horna and colleagues [44,45], this scale has demonstrated adequate levels of reliability and validity. The female participants in the study responded to the items by evaluating their immediate supervisor or senior management personnel. The response options for each item varied from one to six, ranging from “never” to “always”, and the overall scale score was calculated as the average of the ten items. The second scale, which focuses on organizational justice, examines workers’ perceptions of the fair and respectful treatment they receive from their organization. Composed of six items, each with six response options ranging from “never” to “always”, the overall score of this scale is determined as the measure of the items.

3.2.2. The Impact of Natural Disasters and Social Conflicts

The impact of natural disasters and social conflicts in the workplace can be defined as the direct and indirect consequences of these events on workers’ performance, punctuality, and interpersonal relations. These consequences can manifest themselves in various ways. 1. Punctuality: Both natural disasters and social and political conflicts can cause delays in reaching work. For example, an employee may arrive late due to roadblocks resulting from protests or because of infrastructure damaged by a natural disaster. 2. Attendance: The severity of these events may cause employees to miss work, either because conditions do not allow them to travel or because they must attend to emergencies related to the event. 3. Concentration and work performance: Natural disasters and social conflicts can generate stress, anxiety, and worry, affecting workers’ ability to concentrate. 4. Interpersonal relationships: Disasters and conflicts can exacerbate or create tensions in the workplace. Crises can provoke disputes with customers, colleagues, bosses, and supervisors because of disagreements about handling the situation or the cumulative stress of dealing with these adverse circumstances. The scale is a set of eight items. Six inquire about the effects of both categories, disasters and conflicts, on tardiness, absence, or presenteeism at work. It has seven response options ranging from never to more than 20 days during the last 12 months in the workplace. The other two items evaluate the effects that crises can have on disputes with clients, colleagues, bosses, and supervisors due to disagreements over the handling of the situation or the accumulated stress of dealing with these adverse circumstances.

3.2.3. Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

The concept of sexual harassment, according to Fitzgerald, is not limited to behaviors of an explicitly sexual nature but encompasses a broader range of unwanted behaviors that reflect unbalanced power dynamics and create a hostile or intimidating work environment. In Fitzgerald’s framework, sexual harassment is defined as unwanted sexual behaviors in unequal power relationships [7]. These behaviors can range from unwanted sexual advances and requests for sexual favors to more subtle forms of harassment, such as offensive comments, inappropriate jokes, and other behaviors contributing to a hostile work environment. For the present research, we used a brief 10-item version based on Fitzgerald and colleagues’ [7] Sexual Experiences Questionnaire—Workplace (SEQ-W), which measures the level of gender-based harassment, unwanted sexual contact, and sexual coercion of women perpetrated by colleagues, customers, or superiors within an organization. The questions consider the last 12 months, with seven response options (never, 1 time, 2 times, 3 to 5 times, 6 to 10 times, 11 to 19 times, and more than 20 times). This brief scale was validated in Bolivian [44] and Peruvian [8] companies, showing good reliability and construct validity indicators.

3.2.4. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors

Organizational citizenship behaviors refer to the voluntary actions of employees that are not directly recognized via a formal reward system but contribute significantly to the effective functioning of an organization [46]. These behaviors transcend formal job responsibilities and originate from the voluntariness and cooperation of an individual which play crucial roles in the development and success of organizations [47]. The study of work-related civic behavior has evolved and expanded, giving rise to related concepts such as prosocial behavior [48], civic citizenship [49,50], organizational spontaneity [51], and extra-role behavior [52,53]. However, all these concepts share the same definition. A basic element present in various organizational citizenship behavior models is altruism, either toward colleagues or toward the organization (usually called civility). A six-item scale was used to evaluate the presence of these behaviors, using the following six-point response options that address frequency ranging between never and always: 1. Have you voluntarily stayed longer in the company to help your colleagues? 2. Have you voluntarily stayed longer in the company to teach, guide, or train a colleague? 3. Have you voluntarily shared materials or tools from your work so that other colleagues can benefit from their use? 4. Have you used extra time to attend informative activities, training or meetings organized by the company? 5. Have you used extra time to participate in important activities about the company’s image? (For example: charitable activities, congresses, conferences, tributes, etc.) 6. Have you taken care to keep your workplace in good condition (cleaning, taking care of furniture or machinery, etc.)?

3.2.5. Counterproductive Behavior

Often also referred to as workplace deviance, counterproductive behavior is defined as willful behavior that violates significant organizational norms and, in doing so, threatens the well-being of an organization, its members, or both [54]. Typical examples include being late to work on purpose, disobeying instructions, damaging company property, stealing from an employer, or insulting co-workers. Counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior describe extra-role behaviors, i.e., actions that go beyond the formal responsibilities assigned to an employee [55]. Through a meta-analysis, Dalal in 2005 [56] demonstrated that CWB and OCB are correlated but distinct constructs (ρ = −0.32). This variable was measured using a six-item formative scale based on two dimensions from Spector and colleagues’ [57] counterproductive behaviors scale. The scale measures sabotage (3 items). 1. Did he intentionally waste the company’s materials/supplies? 2. Did he intentionally damage a piece of equipment or company property? 3. Did he intentionally litter or throw trash in his workplace? Production deviation is also addressed (3 items). 1. On purpose, did he do his job poorly? 2. On purpose, did he work slowly? 3. On purpose, did he not follow the given instructions at work? Response options ranged from never to 1 time, 2 times, 3 to 4 times, 5 to 6 times, and 7 to 10 times, or more than 10 times.

3.2.6. Turnover Intention

Turnover intention refers to an employee’s cognitive predisposition to voluntarily leave his or her current position in an organization [58]. This intention may manifest in recurrent thoughts about quitting, an active search for new employment opportunities, or an expressed desire to leave should the opportunity arise. It is an important indicator that may precede actual employee turnover. This variable was measured using a three-item reflective scale based on the proposal of Mobley and colleagues [59], which has shown good reliability and validity in companies in Lima [8]. The items, with six-point frequency response options ranging between never and always, were as follows: Have you thought about resigning from your job? Have you been actively searching for a new job? If you could, would you leave your current employment?

3.2.7. Lost Labor Productivity

Lost labor productivity refers to the decreased efficiency and effectiveness with which employees perform their tasks, adversely affecting the organization’s overall performance. This loss can manifest itself in several ways.

- Absenteeism: This refers to when an employee does not attend work. This dimension was measured using five items: because she was sick or had some health ailment or discomfort; to attend to her physical or mental health by visiting the clinic, hospital, health center, etc.; to attend to legal matters (going to court, police stations, documenting procedures, etc.); to avoid running into someone from work; and because she no longer feels well at work (there is a hostile environment, she feels uncomfortable at work, etc.). Response options ranged from never to 1 day, 2 days, 3 to 5 days, 6 to 10 days, 11 to 20 days, or more than 20 days.

- Tardiness: The number of times an employee arrives late for work or after the start of their regular schedule. This dimension was measured using three items: did not miss work but arrived late or was delayed by less than 1 h; did not miss work but arrived late or was delayed by 1 to 2 h; and did not miss work but arrived late or was delayed by more than 2 h. Response options ranged from never to 1 day, 2 days, 3 to 5 days, 6 to 10 days, 11 to 20 days, or more than 20 days.

- Presenteeism: despite being physically present at work, these employees may work at a slower pace than usual, be distracted, have trouble concentrating, feel exhausted or lack energy, or be preoccupied with personal issues that interfere with their ability to perform efficiently. Four items assessed this dimension: Have you had concerns that have affected your work? Have you worked slower than usual? Have you felt tired or exhausted at work? Have you lacked the energy to work? Response options ranged from never to 1 day, 2 days, 3 to 5 days, 6 to 10 days, 11 to 20 days, or more than 20 days.

- Critical work incidents: This dimension addresses difficulties that employees may face with respect to the quality of their work or their performance of their tasks. It also refers to situations in which there are conflicts with colleagues or supervisors due to performance issues or behaviors that do not meet expectations. This dimension was assessed using four items: Have you had difficulties in fulfilling your job duties? Have you encountered problems with the quality of your work? Has your boss reprimanded you for your performance? Have your colleagues reprimanded you for your performance? Response options range from never to 1 time, 2 times, 3 to 5 times, 6 to 10 times, 11 to 20 times, or more than 20 times.

The loss of work productivity was assessed through a second-order reflective scale composed of measures of presenteeism, absenteeism, unpunctuality, and work incidents. Presenteeism, measured using a six-item scale, addressed distractibility and burnout, showing strong reliability and validity indicators. The formative scale of absenteeism and tardiness, although it had lower internal consistency, recorded the number of absences and events of work tardiness. Work incidents were assessed using a reflective scale that recorded problems related to work quality. Based on models developed by Vara-Horna and colleagues [8] and validated in various contexts, these scales demonstrated consistency and applicability in assessing work productivity loss, with satisfactory reliability and validity values.

3.2.8. Psychological Empowerment

Psychological empowerment in the work context can be defined as a multidimensional process and outcome that encompasses strengthening individual beliefs in one’s capabilities and competencies to carry out work tasks and challenges successfully. This dimension focuses particularly on strengthening an individual’s self-efficacy in the workplace. Self-efficacy is a central component of psychological empowerment, understood as confidence in an individual’s ability to execute tasks and overcome obstacles [60]. In the workplace, an individual who is psychologically empowered feels confident in his or her abilities to perform their job well, is confident in his or her ability to handle various work situations, regardless of their complexity, and firmly believes that he or she can address and solve most of the problems encountered in their work environment [61]. Items from Spreitzer’s Psychological Empowerment Instrument (1995) were chosen and modified to measure psychological empowerment. Four items were used with six-point frequency options from never to always. 1. Do you feel confident about your abilities to do a good job? 2. No matter what comes your way at work, do you feel able to handle it? 3. Are you confident that you can handle difficult situations at work? 4. Do you think you could solve most of the problems you encounter at work?

Table 1 presents the reliability and validity of the measurements of the various constructs mentioned above, including second-order scales (denoted with “m”), which are the product of the combination of other scales, reflecting a more complex structure and incorporating multiple dimensions. Internal consistency, assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and Composite Reliability values, reveals good consistency in most scales, with values above 0.707 except in the cases of counterproductive behavior and production deviation. In the cases of composite scales such as sabotage and absenteeism, lower levels of Cronbach’s alpha are observed, which is to be expected since these scales measure non-interchangeable items. The average variance extracted (AVE) also meets the greater than 50% criterion, indicating adequate convergent validity. These findings provide solid and reliable evidence of the measure selection, reflecting robustness in instrumentation and an adequate representation of the constructs under study in both the first-order and second-order scales.

Table 1.

Reliability and validity of measurement scales.

Table 2 presents the Heterotrait/Monotrait Ratio (HTMT), which helps assess discriminant validity between constructs. HTMT values represent the average correlations between different constructs divided by the average correlations within the same construct. Generally, values below 0.85 are indicative that the constructs are different from each other. In addition, bias close to zero and 90% confidence intervals that do not include the value 1 strengthen the discriminant validity evidence. Most of the HTMT ratios in the table meet these criteria, indicating good discriminant validity. However, there are exceptions, such as the ratio between lost labor productivity and the impact of social conflicts and natural disasters (0.860), although this value is consistent with the methodology applied in measuring both variables. The impact of social conflicts and natural disasters focuses on the specific impact on absenteeism, tardiness, presenteeism, and labor relations as a direct result of such events. In contrast, the lost labor productivity construct evaluates productivity affected for any reason. Although this value is close to the 0.85 threshold, the discriminant validity between these constructs holds as the 90% confidence interval does not include unity and the observed bias is close to zero. Therefore, this high correlation does not undermine the discriminant validity but rather reflects the intrinsic nature of how these constructs were defined and measured.

Table 2.

Monotrait/Heterotrait Ratio (HTMT) for discriminant validity assessment.

3.3. Analysis Procedure

The Partial Least Squares Structural Equation (PLS-SEM) method was adopted to validate the proposed model’s hypotheses. This methodology is particularly relevant for investigations in which the primary objective is to explain the variance of the dependent variables. Following the purpose of this study, which focuses on elucidating the impact of fair and equitable management on labor productivity, turnover intention, and sexual harassment in the work environment, considering the effect of social conflicts and natural disasters, the use of the PLS-SEM method is particularly appropriate.

The choice of the PLS-SEM method was also based on its robustness and ability to handle non-normal data. This feature is particularly beneficial in research studies such as the present one, which relies on multivariate survey data with diverse distributions. Additionally, the PLS-SEM method can handle models with multiple dependent and independent variables, which suits the complexity of the model proposed in this study. Finally, the PLS-SEM method allows for the evaluation of the validity and reliability of the scales used to measure the variables in the study. Given that the present research relies on several scales to measure constructs such as work productivity, turnover intention, sexual harassment at work, fair and equitable management, and workplace citizenship, it is essential to assess the validity and reliability of these measures. The PLS-SEM method provides an effective means for such an assessment.

Two key metrics were used to enhance the model’s predictive capability: R² (the coefficient of determination) and the CVPAT (Cross-Validated Predictive Ability Test). The CVPAT provides an out-of-sample prediction approach to determining the model’s predictive error compared to benchmark models [63]. A negative average difference in loss value (ALV) indicates better predictive performance of the PLS-SEM model over benchmarks. The significance of this difference gives insight into the superiority of the PLS-SEM model’s predictive capacity.

It is important to note that the PLS-SEM approach in this study was strengthened by controlling for potentially confounding variables, such as age, monthly salary, educational level, length of service, daily working hours, and firm size. These factors, which may influence the relationships of interest, were considered to provide a more accurate and reliable assessment of the proposed effects.

4. Results

4.1. The Prevalence of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace

Table 3 provides a detailed account of the prevalence of various aspects of sexual harassment at work (WSH) suffered by women in private companies in northern Peru. It reveals that almost a third (32.8%) have faced some manifestation of WSH, which points to a serious and deep-rooted problem. The category of gender harassment, which covers 23.9%, includes stories or jokes with offensive content (21.6%), receiving differential treatment because they are women (7.2%), and sexist comments (13.7%). These data reflect a work culture that seems to tolerate or encourage gender stereotypes, evidencing a generalized disregard for women in the workplace. Regarding unwanted contact, 20.5% of the female respondents reported incidents such as uncomfortable comments about their physical appearance (16.4%), insistence on requests for appointments (11%), and attempts at inappropriate physical contact (4.8%). This underscores a work environment in which basic norms of respect and personal decency seem to be ignored, creating a hostile work atmosphere. Finally, although in a smaller proportion (6.1%), sexually coercive behaviors were reported, including hints of rewards (3.1%), threats of retaliation (4.1%), and attempts at physical coercion (2.4%). Although less prevalent, these figures are especially alarming given that they reflect a direct abuse of power and authority in the work environment.

Table 3.

The prevalence of sexual harassment at work (WSH) during the last 12 months (percentage).

4.2. Social Conflicts and Natural Disasters

Table 4 reveals that social conflicts and natural disasters have considerably impacted the work environment, including concentration, punctuality, attendance, and interpersonal relationships. Notably, natural disasters seem to have a more pronounced impact in most areas, possibly due to their immediate and unpredictable nature. Also, during those times, social conflicts were more intense in the country’s south.

Table 4.

The prevalence of labor impacts due to social conflicts and natural disasters in private companies in northern Peru during the last 12 months.

4.3. Equitable and Fair Management

The data presented in Table 5 reflect two main dimensions: organizational justice and equitable management by management personnel. These dimensions, taken together, provide an overall perspective of the organizational culture and leadership ethic in the companies studied. In general, the data reflect an overall positive picture of organizational justice culture and equitable management in the companies studied, with strengths in areas such as respect, communication, and the promotion of creativity. However, critical areas for improvement are also identified, particularly around the perception of fair rewards and sanctions and the admission of mistakes by leadership.

Table 5.

Prevalence of equitable and fair management indicators over the last 12 months.

Regarding Organizational Justice, most respondents (82.2%) feel that their company has treated them with dignity and respect, and 80.3% feel respected by their company. Similarly, 66.1% of the participants feel that their company makes them valuable and important. While this figure is positive, it indicates a possible area for improvement compared to the rates of respectful treatment. Finally, the numbers show a more notable discrepancy regarding fair rewards and sanctions. Only 49% believe that their company has rewarded its staff fairly, and 53.8% believe that sanctioning, when necessary, has been fair. Also, 53.8% believe that there is no favoritism.

Regarding the equitable management of management personnel, 75.5% of the respondents feel that management personnel promote creativity, reflecting a positive attitude toward innovation. Regarding communication and respect, 87.5% of the respondents reported assertive communication, 87.8% reported equal treatment, and 86.2% reported conflict management without retaliation. On the other hand, 80.5% reported generosity and recognition of merit, while 65.4% felt that the reward was fair. This could point to a positive perception of leadership ethics but also highlights a possible gap in the perception of reward fairness. In terms of admitting mistakes and attention to problems, these aspects have lower figures, with 51.6% admitting mistakes and 63.6% in attention to problems.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

Table 6 presents the correlation matrix between the variables. Descriptive statistics such as the mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis are also included. The positive and significant correlation between lost labor productivity and the impact of social conflicts and natural disasters (r = 0.609, p < 0.01) reflects a direct relationship between these phenomena. Likewise, a positive correlation is observed between sexual harassment at work and turnover intention (r = 0.361 and r = 0.330, p < 0.01, respectively), indicating a possible connection with negative aspects of the work environment. Conversely, equitable management and organizational justice show negative and significant correlations with these problematic variables, suggesting a protective role. Psychological empowerment is positively related to organizational citizenship behaviors (r = 0.294, p < 0.01), highlighting its possible contribution to well-being at work. The high skewness and kurtosis values of some variables warn about the non-normality of the distribution, which should be considered in further analyses.

Table 6.

Correlation matrix between variables.

Structural equation modeling was used to evaluate the direct, indirect, and total effects of equitable management and the impact of social conflicts and natural disasters (ICSDN) on the dependent variables (see Table 7). Overall, the results suggest that equitable management in the workplace can have beneficial effects in terms of reducing negative behaviors and fostering positive behaviors and attitudes. In addition, the impact of social conflicts and natural disasters may act as a mediator in some of these relationships, underscoring the importance of considering the broader context in which organizations operate.

Table 7.

The direct, indirect, and total effects of equitable management on WSH and various productivity indicators, depending on the impact of social conflicts and natural disasters.

Direct effects: Equitable management presented significant effects on most of the dependent variables. Counterproductive behaviors (β = −0.250, p < 0.001), sexual harassment at work (β = −0.292, p = 0.002), and turnover intention (β = −0.469, p < 0.001) showed negative relationships with equitable management, suggesting that greater equitable management is associated with decreases in these undesirable behaviors. On the other hand, positive relationships were observed between equitable management and organizational citizenship behaviors (β = 0.196, p < 0.001) and psychological empowerment (β = 0.241, p < 0.001), indicating that equitable management may foster positive behaviors and empowerment in the workplace.

Indirect effects: Indirect effects through the impact of social conflict and natural disasters (ICSDN) varied. The significant negative relationship between equitable management and occupational sexual harassment through ICSDN (β = −0.056, p = 0.028) suggests that equitable management may buffer the negative impact that social conflicts and natural disasters have on occupational sexual harassment. That is, equitable management could act as a protective shield against the effects of conflicts and disasters in this context, decreasing the incidence of harassment. Similarly, the significant negative relationship with turnover intention (β = −0.058, p = 0.002) indicates that equitable management may reduce employees’ turnover intention in the presence of social conflicts and natural disasters. This underscores the importance of fairness and equity in management as a retention mechanism, especially in challenging contexts. On the other hand, the strong negative effect on lost labor productivity (β = −0.153, p < 0.001) highlights that equitable management can mitigate the effects of social conflicts and natural disasters on the work environment and economic performance. Equitable management appears to be crucial in preserving productivity in adverse situations.

Hypothesis Contrast:

Hypothesis 1.

It was postulated that companies implementing equitable management would have lower incidences of sexual harassment, counterproductive behaviors, and intentions of labor turnover. Consistent with this hypothesis, the results show that equitable management was negatively related to counterproductive behaviors, β = −0.250 and p < 0.001; sexual harassment at work, β = −0.292 and p = 0.002; and turnover intentions, β = −0.469 and p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 2.

It was anticipated that the implementation of equitable management in companies would be directly related to positive workplace attitudes and behaviors. In support of this hypothesis, a positive relationship was found between equitable management and organizational citizenship behaviors, β = 0.196 and p < 0.001, and psychological empowerment, β = 0.241 and p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 3.

It was postulated that social conflicts and natural disasters (ICSDN) would increase sexual harassment in the workplace, turnover intention, and would harm labor productivity. Consistent with this hypothesis, the results indicate that ICSDN was positively related to sexual harassment in the workplace, β = 0.244 and p = 0.027; to turnover intention, β = 0.252 and p < 0.001; and to a significant loss in labor productivity, β = 0.662 and p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 4.

It was expected that in companies with equitable management, the adverse impact of social conflicts and natural disasters on sexual harassment at work and productivity would be attenuated. The indirect results support this hypothesis, showing that equitable management can act as a protective shield against the effects of conflicts and disasters, β = −0.056 and p = 0.028 for sexual harassment, and β = −0.153 and p < 0.001 for lost labor productivity.

5. Discussion

This study provides robust empirical evidence, addressing a gap in the scientific literature by highlighting the importance of equitable and fair management for organizations, taking into account the impact of crisis. Its uniqueness lies in two key aspects. 1. It introduces a novel perspective by examining the role of equitable and fair management in the relationships among social conflict, natural disasters, workplace sexual harassment, and lost labor productivity. Unlike previous research that analyzed these components in isolation, this study presents an integrative theoretical framework which underscores the interactions between crisis scenarios (social conflict and natural disasters) with workplace sexual harassment and the subsequent impact on lost labor productivity, allowing for a more holistic understanding of these dynamics. 2. This study highlights the importance of organizational interventions for mitigating workplace sexual harassment, suggesting that fair and equitable work management can be practical tools for preventing gender-based violence, even in crisis contexts.

Our results underscore the critical importance of equitable and fair management within the workplace, reinforcing and extending previous findings in the literature [22,64]. Consistent with our hypotheses, we find that equitable and fair management is associated with improved organizational citizenship behaviors, lower workplace sexual harassment, lower impact of social conflict and natural disasters, lower turnover intention, and less loss of work productivity. These findings support Organizational Justice Theory, suggesting that when employees perceive that they are treated fairly and justly, they respond with more positive behaviors and more significant commitment to the organization, which may have protective effects in the face of crises.

On the other hand, our results also indicate that social conflicts and natural disasters can significantly impact workplace sexual harassment, turnover intention, and the loss of work productivity. This finding is consistent with the literature, suggesting that disruptive behaviors may increase during periods of stress and crisis and productivity may be negatively affected [65,66,67]. These results underscore the threat to organizational well-being posed by uncontrollable external factors, such as social conflicts and natural disasters. Interestingly, however, we did not find a significant relationship between these events and work-related citizenship behavior, suggesting that these positive behaviors may be more resilient to external influences or that they may be more strongly influenced by factors internal to the organization.

The findings indicate that fair and equitable management not only directly affects variables such as intention to quit, sexual harassment, and counterproductive behaviors but also mitigates the negative impacts of social conflicts and natural disasters. In other words, fair and equitable practices are essential in times of crisis to reduce adverse effects on labor productivity and employee well-being. This evidence shows the strategic value of violence prevention in organizations and can be used to overcome some implicit managerial resistance against prevention [8].

As for organizational citizenship behaviors, these appear to be resilient to times of crisis, much like the results of Bogler and colleagues [68], who found that teachers increased these behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Organizational citizenship behaviors are extra-role actions that companies desire. Demonstrating these behaviors is commonly known as “putting your shirt on” and, as evidenced by the results, they can be promoted through equitable management and, even better, they are very resistant to times of crisis, preventing productivity from declining during those periods.

A variable closely associated with this process is psychological empowerment, which is promoted by equitable management and maintaining resilience in crises. Indeed, empowering female employees can lead to positive outcomes for individuals and an organization. Empowerment can take the form of greater autonomy, control over work, and access to resources and opportunities. Equitable and fair management could empower female employees, thereby protecting them from WSH and increasing their productivity.

Additional extra-role behaviors—their opposites—are counterproductive behaviors, which are voluntary actions that consciously undermine a company’s productivity. Just like civic behavior, but acting in the opposite direction, these behaviors can be reduced with fair and equitable management, and they are also resistant to times of crisis.

Concerning sexual harassment in the workplace, our results suggest that fair management can act as a protective shield, especially in contexts in which social conflicts and natural disasters intensify the risk of such behaviors. It has been verified that social conflicts and natural disasters increase sexual harassment at work, but this increase is mitigated by fair and equitable management. The exact route occurs with the loss of labor productivity and the turnover intention. In the first case, equitable management has a modest direct effect, but its influence is magnified through its indirect effects by mitigating its impacts in social conflicts or natural disasters. Unlike extra-role behaviors, these losses are involuntary and are the most affected by social or natural crises.

Gender-based violence and sexual harassment at work have previously been found to have a direct negative impact on the productivity and performance of female workers [8,69]. Not only is working time lost due to the harassment itself and the responses it generates but there are also negative effects in terms of stress, low self-esteem, and a lack of concentration among those affected [8,10,70]. In times of crisis, reinforcing prevention and ensuring a safe work environment can help minimize these losses in productivity and performance.

Strengthening actions to prevent gender-based violence during crises is not only a matter of human rights. It can also have tangible benefits for the company regarding productivity, staff engagement, reputation, and legal compliance. Companies that implement equitable and fair management tend to have more committed and loyal female employees. By demonstrating a solid commitment to preventing gender-based violence, even in times of crisis, the company sends a clear message that it values its staff and cares about their well-being. This commitment can translate into greater dedication and effort from female employees, resulting in long-term benefits for the company.

Additionally, the active and continuous prevention of gender-based violence can positively impact the company’s reputation. This can be especially important in times of crisis when the company needs to maintain the trust and goodwill of its stakeholders. Conversely, inaction or perceived indifference to gender-based violence can seriously damage a company’s reputation and have long-lasting effects even after the crisis has passed. Moreover, companies have a responsibility to contribute to the sustainable development of society, including the promotion of gender equality and the prevention of gender-based violence. In times of crisis, this responsibility does not disappear but can become even more critical. Preventing gender-based violence can be crucial to a company’s response to the crisis, demonstrating its commitment to social responsibility and sustainable development. Finally, many countries have laws and regulations that require companies to take measures to prevent and respond to sexual harassment in the workplace. Failure to comply with these obligations can result in significant fines and lawsuits from affected workers. In this regard, maintaining and reinforcing prevention measures during crises can be an effective strategy to avoid these legal risks.

The term prevention, as used throughout this manuscript, signifies proactive measures to mitigate the onset or escalation of gender-based violence and harassment within workplace settings. Prevention goes beyond mere reactionary measures to address reported incidents. Instead, it seeks to create an environment in which such incidents are less likely to arise in the first place. This involves cultivating an organizational culture anchored in respect, awareness, and zero tolerance for harassment or violence. Equitable management plays a pivotal role in prevention by ensuring fairness, inclusivity, and a commitment to addressing systemic issues that can foster gender violence and harassment. When management upholds principles of equity, it sends a clear message about organizational values, thereby shaping individual behaviors and collective norms. An equitable management approach encompasses transparent communication, the involvement of diverse voices in decision-making processes, and the consistent enforcement of anti-harassment policies. Such an environment not only diminishes the opportunities for sexual harassment but also instills confidence among employees about the organization’s commitment to their safety and well-being. By promoting a sense of collective ownership and shared values, equitable management can effectively catalyze behavioral change, making harassment less likely to occur and more likely to be reported and addressed if it does.

5.1. Limitations

Although this study attempted to be as rigorous as possible, given the context, there are some necessary limitations to consider. 1. The results were obtained specifically from private companies in northern Peru. Therefore, their generalizability to other settings (non-profit organizations and state-owned enterprises) or different geographic and cultural regions is still being determined. It is worth mentioning that in southern Peru, contemporary social conflicts were more intense, so research in that context could enrich the understanding of the phenomenon. 2. A cross-sectional design: Due to its cross-sectional design, this study has limitations in establishing causal inferences. While we identified an association between equitable and fair management and specific labor outcomes, direct causality cannot be affirmed. Future longitudinal research may shed light on these causal relationships. 3. Self-reporting: Because it relied on self-reported surveys, this study is susceptible to biases, such as social desirability bias. The responses may reflect what the respondents considered socially desirable rather than their actual experiences. Future research should consider integrating other data sources, such as supervisor evaluations or organizational records, to address this limitation. 4. The variables not considered: Although several variables were considered in this study, some that could be relevant were likely omitted. Although control variables such as age, education level, salary, length of service, and company size were included, unmeasured variables could alter the interpretation of the results. Future research is encouraged to consider incorporating and analyzing these potential variables.

5.2. Implications

The research has several implications to consider, which are described below.

5.2.1. Practical Implications

This study highlights the importance of companies maintaining and reinforcing equitable and fair management, even during periods of crisis caused by social conflict or natural disasters. Leaders and managers must consider equity and fairness fundamental aspects of their management in decision making and daily interactions with employees. Specifically, efforts to minimize workplace sexual harassment should not be neglected during periods of crisis. On the contrary, these periods may require an even greater focus on preventing workplace sexual harassment given its potentially more severe impact on the productivity and well-being of female employees during these times. Strategies to maintain workplace citizenship and reduce turnover intention should also be a priority as these factors can help companies maintain their operability and social cohesion during periods of crisis.

Rooted in historical contexts and socio-cultural norms, gender power inequalities remain pervasive in many workplaces, influencing interpersonal dynamics, organizational structures, and management styles. One manifestation of these deep-seated inequalities is the prevalence of sexual harassment, often perpetuated by and entwined with power imbalances. Equitable and fair management, while a commendable goal, is also a pivotal tool for minimizing these imbalances. These gender power disparities have implications that extend beyond just incidents of harassment. They impact decision-making, leadership styles, representation, and the overall ethos of an organization. Despite their competencies, women often find themselves sidelined, their voices marginalized, and their contributions undervalued. This deprives organizations of diverse perspectives and perpetuates a cycle in which power remains concentrated and unchallenged.

To truly address and rectify these power imbalances and, in turn, reduce instances of sexual harassment, organizations need to take proactive measures. This includes ensuring better representation of women in decision-making roles and leadership positions. Such representation serves a dual purpose: it breaks the traditional concentration of power, and it t establishes role models and advocates within the system, empowering other women and promoting a culture of equity.

Incorporating gender-sensitive policies and ensuring women’s representation is not just about numbers; it is about restructuring power dynamics. As emphasized previously, equitable and fair management is a cornerstone in this restructuring, ensuring that all employees, regardless of gender or position, are treated fairly, with dignity and without favoritism. It becomes imperative that recommendations and suggestions derived from studies on workplace dynamics prioritize and emphasize the need for gender equity at all organizational levels.

5.2.2. Policy Implications

Positioned against the backdrop of Convention No. 190 (C190) of the International Labour Organization (ILO), this study emerges as a crucial research contribution that reinforces the Convention’s call for the eradication of workplace violence and harassment, especially gender-based violence and harassment. By examining the role of equitable management in preventing workplace sexual harassment, especially during crises, this study not only aligns with the objectives of C190 but also adds depth and nuance to it. While providing a robust framework, the Convention necessitates empirical evidence and context-specific applications to achieve its goals. With its comprehensive survey in northern Peru, the study delivers insights that underline the Convention’s essence, demonstrating how equitable management can be a formidable buffer against the detrimental effects of social conflicts and natural disasters. Particularly salient are the study’s findings, which show significant reductions in counterproductive behaviors and sexual harassment in environments that prioritize equity. These revelations are pivotal for nations like Peru that have ratified C190, showcasing tangible mechanisms like equitable management that can be employed to adhere to the Convention’s mandates.

5.2.3. Implications for Future Research

This study provides empirical evidence of relationships between equitable and fair management and various facets of work behavior during periods of crisis. However, future research could explore how these relationships play out in different contexts and in different crises. In addition, other possible mechanisms through which equitable and fair management may influence work behavior could be examined.

5.2.4. Training in Equitable and Fair Management with a Focus on Gender Violence Prevention

As trainers of future leaders and managers, business schools have an essential responsibility to incorporate and emphasize modules or courses dedicated to equitable and fair management which are mainly focused on preventing gender-based violence. Students must acquire competencies that enable them to recognize and address inequities, apply principles of justice in decision making, manage conflicts impartially, and be specially trained to identify and act in situations of gender-based violence. Introducing case studies focused on ethical dilemmas and real management situations, including specific scenarios related to gender-based violence, will enable students to confront and resolve these problems from an equitable and fair perspective. Simulations can provide practical experiences in ethical decision-making and management of sensitive situations. Class discussions and debates should encourage students to reflect on the importance of equitable and fair management, how it influences the work environment, the reputation and long-term sustainability of organizations, and the intrinsic responsibility to prevent and combat gender-based violence. Finally, future business leaders must understand how equity, fairness, and especially the prevention of gender-based violence become even more relevant during periods of crisis. These essential aspects can be key to maintaining team cohesion, productivity, and well-being.

5.2.5. Comprehensive Workplace Implications for Prevention and Equitable Management

The findings of this research underscore the imperative for policies that advocate and uphold equitable and fair management in the workplace. Such policies should champion fairness in decision-making processes, ensure every voice is heard, and provide precise, transparent mechanisms for resolving workplace conflicts. Alongside these measures, an emphasis on preventing and addressing sexual harassment is paramount. For these policies to be effective, they must be co-created with the active consultation and participation of workers, leveraging the power of social dialogue to ensure both relevance and buy-in. Furthermore, fostering a culture of workplace citizenship, where individuals actively contribute to the betterment of their organizational community, should be a priority. This becomes especially pertinent during times of crisis, when solidarity and mutual support can play a pivotal role in resilience. Additionally, refining workplace policies to incorporate best practices in advocacy, complaints mechanisms, and prevention programs ensures a comprehensive approach. Intertwining these strategies with Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) protocols, notably risk assessments, further solidifies the commitment to preventing GBVH. By implementing these multi-faceted measures, organizations can move toward creating environments where every individual feels valued, respected, and, most importantly, safe.

6. Conclusions

Workplace environments are subject to several stresses and strains that can be exacerbated during periods of social crisis or natural disasters. During these times of adversity, organizations face increased challenges, such as productivity losses, increased turnover intention, and the prevalence of disruptive behaviors such as workplace sexual harassment. Although these labor problems seem evident and urgent, the literature on human resource management has shown that efforts to prevent these problems can be disjointed during periods of crisis, leading to a chain of detrimental effects aggravated by the crisis. However, the present research conducted in companies located in northern Peru presents a different perspective: maintaining and reinforcing equitable and fair management during these crises may be the key to mitigating these labor problems. This study helps to understand how and why equitable and fair management can have this protective effect. Thus, equitable and fair management could be an effective shield against the adverse effects of crisis periods while fostering workplace citizenship and preventing destructive workplace behaviors. This study sheds light on these processes, providing valuable insights for human resource management and contributing to the literature on preventing gender-based violence in the workplace.

Sexual harassment in the workplace is a persistent problem in various organizational contexts. However, in crises such as those examined in this study, the prevalence and severity of sexual harassment can be exacerbated. Therefore, organizations should be vigilant and take additional preventive measures. Because crises can intensify negative behaviors, organizations should reinforce their sexual harassment policies and conduct frequent training on sexual harassment, especially when anticipating or experiencing a crisis. In times of crisis, it is essential that employees feel they can communicate their concerns without fear of retaliation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.-H., Z.A.-G. and A.D.-R.; methodology, A.V.-H., Z.A.-G., L.Q.-C. and A.D.-R.; software, A.V.-H. and Z.A.-G.; validation, A.V.-H.; formal analysis, A.V.-H.; investigation, Z.A.-G., L.Q.-C., D.S.-R. and A.D.-R.; resources, L.Q.-C.; data curation, A.V.-H. and Z.A.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.-H.; writing—review and editing, Z.A.-G., L.Q.-C. and A.D.-R.; visualization, A.V.-H.; supervision, A.D.-R., D.S.-R. and L.Q.-C.; project administration, A.D.-R., D.S.-R. and L.Q.-C.; funding acquisition, A.V.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been financed by the European Union and the Spanish Cooperation, through the management of the Chamber of Commerce of Lima (CCL), within the framework of the project “Violencia de Género contra las Mujeres: fortalecer la prevención en el sector privado”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by International Ethics Committee of the Universidad de San Martín de Porres (HHS IRB-00003251; FWA-00015320) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement