Should Brands Talk about Environmental Sustainability Aspects That “Really Hurt”? Exploring the Consequences of Disclosing Highly Relevant Negative CSR Information

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Practical Relevance

1.2. State of Research, Research Gaps and Main Research Questions

2. Conceptual Background

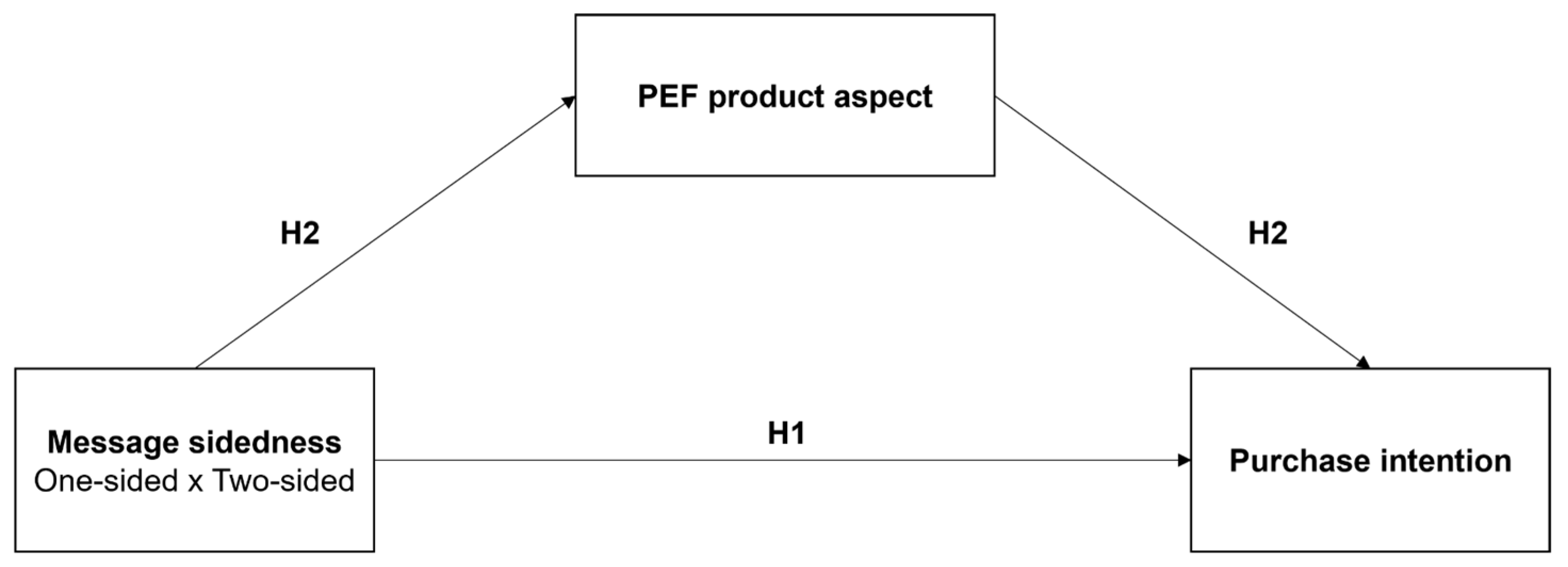

3. Hypotheses

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Design

4.2. Measures

4.3. Participants

5. Results

5.1. Pretest Results

5.2. Realism and Manipulation Checks

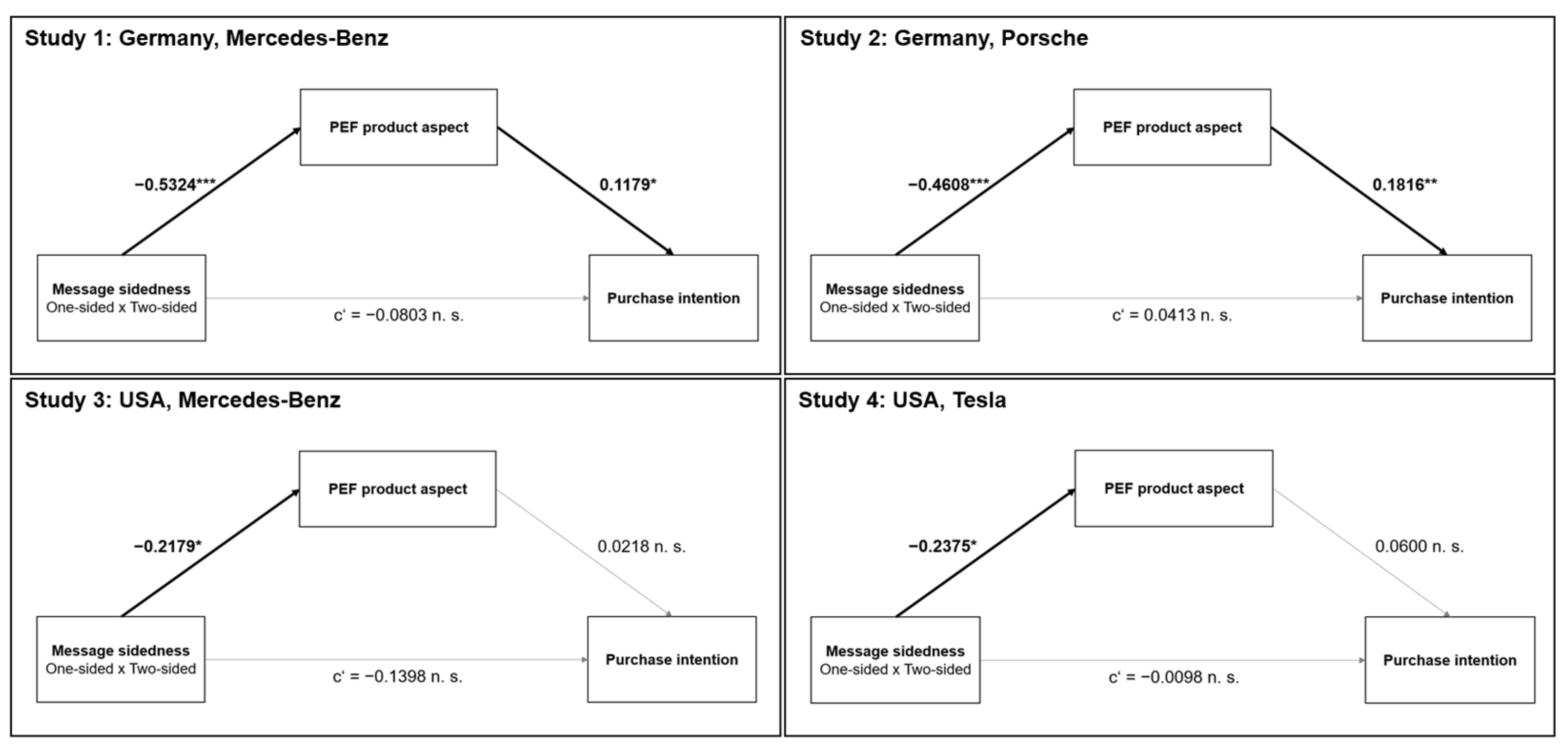

5.3. Hypotheses Tests

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Discussion and Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.2.1. Managerial Implications

6.2.2. Political Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Chapter 11: Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/chapter/chapter-11/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Simon-Kucher & Partners. 2022 Global Sustainability Study: The Growth Potential of Environmental Change. Available online: https://www.simon-kucher.com/en/insights/2022-global-sustainability-study-growth-potential-environmental-change (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Afzali, H.; Kim, S.S. Consumers’ Responses to Corporate Social Responsibility: The Mediating Role of CSR Authenticity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities. GREEN PAPER: Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2001:0366:FIN:en:PDF (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Hackston, D.; Milne, M.J. Some determinants of social and environmental disclosures in New Zealand companies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1996, 9, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder-Webb, L.; Cohen, J.R.; Nath, L.; Wood, D. The Supply of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures among U.S. Firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalet, S.; Kelly, T.F. CSR Rating Agencies: What is Their Global Impact? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 94, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perks, K.J.; Farache, F.; Shukla, P.; Berry, A. Communicating responsibility-practicing irresponsibility in CSR advertisements. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1881–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and Green Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Green Skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate Hypocrisy: Overcoming the Threat of Inconsistent Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörner, A. Ärger um Clean-Diesel-Werbung. Available online: https://www.handelsblatt.com/unternehmen/industrie/volkswagen-in-den-usa-aerger-um-clean-diesel-werbung/13378548.html (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- ADAC. Abgasskandal: Diese Rechte Haben Diesel-Besitzer. Available online: https://www.adac.de/rund-ums-fahrzeug/auto-kaufen-verkaufen/abgasskandal-rechte/rechte-verbraucher/ (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Kim, S.-B.; Kim, D.-Y. Antecedents of Corporate Reputation in the Hotel Industry: The Moderating Role of Transparency. Sustainability 2017, 9, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbański, M.; ul Haque, A. Are You Environmentally Conscious Enough to Differentiate between Greenwashed and Sustainable Items? A Global Consumers Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jung, J.-S. The Effect of CSR Attributes on CSR Authenticity: Focusing on Mediating Effects of Digital Transformation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcilar, M.Y.; Demirgünes, B.K. Developing Perceived Greenwash Index and Its Effect on Green Brand Equity: A Research on Gas Station Companies in Turkey. Int. Bus. Res. 2017, 10, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futerra. Consumer Research. Available online: https://www.wearefuterra.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Futerra-Honest-Product-V5-1.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Hahn, R.; Lülfs, R. Legitimizing Negative Aspects in GRI-Oriented Sustainability Reporting: A Qualitative Analysis of Corporate Disclosure Strategies. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, T.; Fisher, J. A psychological model of transparent communication effectiveness. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2020, 26, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, B. Give the Emperor a Mirror: Toward Developing a Stakeholder Measurement of Organizational Transparency. J. Public Relat. Res. 2009, 21, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lobo, A.; Leckie, C. The role of benefits and transparency in shaping consumers’ green perceived value, self-brand connection and brand loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, N.; Lee, E.; Lee, S.H.; Yang, S.-U. We’re All in This Together: Legitimacy and Coronavirus-Oriented CSR Messaging. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, A.E.; Hoyer, W.D. An Integrative Framework for Understanding Two-sided Persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, J.; Brühl, R. Can bad news be good? On the positive and negative effects of including moderately negative information in CSR disclosures. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 97, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudie Jeans. Lofty Lo Vintage Black. Available online: https://www.nudiejeans.com/de/product/lofty-lo-vintage-black (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Ellen, P.S.; Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A. Building Corporate Associations: Consumer Attributions for Corporate Socially Responsible Programs. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M. Two-sided advertising: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2006, 23, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settle, R.B.; Golden, L.L. Attribution Theory and Advertiser Credibility. J. Mark. Res. 1974, 11, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, L.L.; Alpert, M.I. Comparative Analysis of the Relative Effectiveness of One- and Two- Sided Communication for Contrasting Products. J. Advert. 1987, 16, 18–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M. Explaining the joint effect of source credibility and negativity of information in two-sided messages. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 1032–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Martino Publishing: Mansfield, CT, USA, 1958; ISBN 978-1614277958. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.E.; Davis, K.E. From Acts to Dispositions: The Attribution Process in Person Perception. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2nd ed.; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 219–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, H.H. The processes of causal attribution. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.T.; Malone, P.S. The correspondence bias. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkes, V.S. Recent Attribution Research in Consumer Behavior: A Review and New Directions. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 14, 548–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.R.; Stöckl, A.; Veale, R.; Brouard, J.; Cavicchi, A.; Faraoni, M.; Larreina, M.; Lecat, B.; Olsen, J.; Rodriguez-Santos, C.; et al. Using attribution theory to explain tourists’ attachments to place-based brands. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samu, S.; Wymer, W. Cause marketing communications: Consumer inference on attitudes towards brand and cause. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 1333–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Gong, Q.; Huang, Y. How do destination social responsibility strategies affect tourists’ intention to visit? An attribution theory perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, G.; Premazzi, K.; Cugini, A. “I will pay you more, as long as you are transparent!”: An investigation of the pick-your-price participative pricing mechanism. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Dawar, N. Corporate social responsibility and consumers’ attributions and brand evaluations in a product–harm crisis. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Nazir, M.S.; Ali, I.; Khalid, A.; Shaukat, M.Z.; Anwar, F. “Do Good, Have Good”: A Serial Mediation Analysis of CSR with Customers’ Outcomes. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Kwak, D.H.; Bagozzi, R.P. Cultural cognition and endorser scandal: Impact of consumer information processing mode on moral judgment in the endorsement context. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Talwar, S.; Madanaguli, A.; Srivastava, S.; Dhir, A. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and hospitality sector: Charting new frontiers for restaurant businesses. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 1234–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. Psychologie der Interpersonalen Beziehungen, 1st ed.; Klett: Stuttgart, Germany, 1977; ISBN 9783129234105. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.E.; Hunt, S.D. Attributional Processes and Effects in Promotional Situations. J. Consum. Res. 1978, 5, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M. Understanding two-sided persuasion: An empirical assessment of theoretical approaches. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 615–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginder, W.; Kwon, W.-S.; Byun, S.-E. Effects of Internal–External Congruence-Based CSR Positioning: An Attribution Theory Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A. Feeling Good by Doing Good: Employee CSR-Induced Attributions, Job Satisfaction, and the Role of Charismatic Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.-J.; Wirtz, B.W.; Weyerer, J.C. Determinants of online review credibility and its impact on con-sumers’ purchase intention. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Goldsmith, R.E. Corporate Credibility’s Role in Consumers’ Attitudes and Purchase Intentions When a High versus a Low Credibility Endorser Is Used in the Ad. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanoor, S.; Grewal, D.; Blodgett, J. Ads promoting OTC medications: The effect of ad format and credibility on beliefs, attitudes, and purchase intentions. J. Bus. Res. 1997, 40, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Z. The Effect of Brand Credibility on Consumers’ Brand Purchase Intention in Emerging Economies: The Moderating Role of Brand Awareness and Brand Image. J. Glob. Mark. 2010, 23, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschate-Fischer, N.; Schandelmeier, S. A guideline for designing experimental studies in marketing research and a critical discussion of selected problem areas. J. Bus. Econ. 2014, 84, 793–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Monroe, K.B.; Krishnan, R. The Effects of Price-Comparison Advertising on Buyers’ Perceptions of Acquisition Value, Transaction Value, and Behavioral Intentions. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Lin, C.-Y.; Weng, C.-S. The Influence of Environmental Friendliness on Green Trust: The Mediation Effects of Green Satisfaction and Green Perceived Quality. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10135–10152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Veirman, M.; Hudders, L. Disclosing sponsored Instagram posts: The role of material connection with the brand and message-sidedness when disclosing covert advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 94–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karande, K.; Magnini, V.P.; Tam, L. Recovery Voice and Satisfaction After Service Failure. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 10, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, B.L.; Ruth, J.A. Is a Company Known by the Company It Keeps? Assessing the Spillover Effects of Brand Alliances on Consumer Brand Attitudes. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Muhmin, A.G. Explaining consumers’ willingness to be environmentally friendly. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlen, G.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Diamantopoulos, A. Measuring ecological concern: A multi-construct perspective. J. Mark. Manag. 1993, 9, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Battocchio, A.F. Effects of transparent brand communication on perceived brand authenticity and consumer responses. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2021, 30, 1176–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A.; Olson, J.C. Are Product Attribute Beliefs the Only Mediator of Advertising Effects on Brand Attitude? J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781462549030. [Google Scholar]

- Akinwande, M.O.; Dikko, H.G.; Samson, A. Variance Inflation Factor: As a Condition for the Inclusion of Suppressor Variable(s) in Regression Analysis. Open J. Stat. 2015, 5, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.T. Attribution and interpersonal perception. In Advanced Social Psychology; Tesser, A., Ed.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 99–147. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, D.T. Inferential Correction. In Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment; Gilovich, T., Griffin, D., Kahneman, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 167–184. ISBN 9780521792608. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, D.T.; Pelham, B.W.; Krull, D.S. On cognitive busyness: When person perceivers meet persons perceived. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Global Automotive Consumer Study: Key Findings: Global Focus Countries. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Consumer-Business/us-2022-global-automotive-consumer-study-global-focus-final.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- PwC. Mainland China and HK Luxury Market Insights: “Retrieve Customer Values for Growth and Sustainability”. Available online: https://www.pwccn.com/en/retail-and-consumer/china-hk-luxury-market-insights-feb2023.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2023).

| Study | Average Age | Percentage of Female Participants (%) | Percentage of People with an Annual Gross Household Income of More Than 40,001 Euro/USD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (Germany, Mercedes-Benz) | 41.16 | 49.9 | 88.2 |

| Study 2 (Germany, Porsche) | 41.94 | 48.0 | 85.2 |

| Study 3 (USA, Mercedes-Benz) | 45.94 | 63.7 | 89.7 |

| Study 4 (USA, Tesla) | 42.93 | 65.1 | 84.3 |

| Study 1 (Germany, Mercedes-Benz) | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Indirect effect | Message sidedness → PEF of product aspect → Purchase intention | −0.0628 | 0.0374 | −0.1459 | −0.0028 |

| Total effect | Message Sidedness → Purchase intention | 0.0803 | 0.1417 | −0.1913 | 0.3589 |

| Study 2 (Germany, Porsche) | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Indirect effect | Message sidedness → PEF of product aspect → Purchase intention | −0.0837 | 0.0350 | −0.1604 | −0.0244 |

| Total effect | Message Sidedness → Purchase intention | 0.0413 | 0.1565 | −0.2665 | 0.3492 |

| Study 3 (USA, Mercedes-Benz) | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Indirect effect | Message sidedness → PEF of product aspect → Purchase intention | −0.0048 | 0.0178 | −0.0454 | 0.0284 |

| Total effect | Message Sidedness → Purchase intention | −0.1398 | 0.1390 | −0.4131 | 0.1334 |

| Study 4 (USA, Tesla) | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Indirect effect | Message sidedness → PEF of product aspect → Purchase intention | −0.0143 | 0.0189 | −0.0564 | 0.0206 |

| Total effect | Message Sidedness → Purchase intention | −0.0098 | 0.1309 | −0.2671 | 0.2476 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Müller, J.; Schade, M.; Burmann, C. Should Brands Talk about Environmental Sustainability Aspects That “Really Hurt”? Exploring the Consequences of Disclosing Highly Relevant Negative CSR Information. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215909

Müller J, Schade M, Burmann C. Should Brands Talk about Environmental Sustainability Aspects That “Really Hurt”? Exploring the Consequences of Disclosing Highly Relevant Negative CSR Information. Sustainability. 2023; 15(22):15909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215909

Chicago/Turabian StyleMüller, Jonas, Michael Schade, and Christoph Burmann. 2023. "Should Brands Talk about Environmental Sustainability Aspects That “Really Hurt”? Exploring the Consequences of Disclosing Highly Relevant Negative CSR Information" Sustainability 15, no. 22: 15909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215909

APA StyleMüller, J., Schade, M., & Burmann, C. (2023). Should Brands Talk about Environmental Sustainability Aspects That “Really Hurt”? Exploring the Consequences of Disclosing Highly Relevant Negative CSR Information. Sustainability, 15(22), 15909. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215909