Abstract

Today, customers see businesses as more than just profit seekers, they see them as organizations that are concerned about the well-being of their societies. Therefore, businesses have made sustainability a primary focus by implementing green marketing tactics to encourage consumers to buy green goods. The intention to buy green products was examined in relation to factors such as eco-labelling, green packaging and branding, and green products, premium, and pricing. This study analyses a model that incorporates green marketing techniques based on the responses of 450 people to a survey. In addition, the paper investigates the moderating effect of green brand image and customer views on the environment on the link between green marketing and green purchase intentions. This study’s framework is confirmed by using structural equation modelling (SEM). The findings of this study show that green marketing methods significantly and positively affect customers’ intentions to make environmentally friendly purchases. When looking at the path coefficient between green marketing techniques and green purchase intents, we discovered that green brand image and customer environmental attitudes considerably moderated this relationship. This study provides regional and international enterprises and governments with information on how to enhance consumers’ intentions to make green purchases. Significant findings from this study support favourable social behaviour toward green marketing. Towards the examination of the consumers’ green purchasing intents, this research underlined the importance and function of green brand image and customer attitudes regarding the environment. The packing of the items should be eco-friendly and prevent excessive paper and plastic packaging. Companies should leverage the environmental features of their products for branding purposes.

1. Introduction

Human industrial practices are creating an excess of greenhouse gas emissions (such as CO2 and methane), resulting in physical and chemical changes in soil, air space, and seawater, and leading to more unpredictable climatic variations such as famine, severe thunderstorms, and warmer temperatures [1]. Reduction and variation in rainfall events is due to climate change, which has a great impact on the agriculture sector.

Human activities are involved in estimations that global warming could reach approximately 10 °C. The estimation of increasing anthropogenic global warming per decade is 0.2 °C (likely between 0.1–0.3 °C). If global warming keeps on increasing at the same pace, then it will reach 1.5 °C between 2030 and 2052 [2]. According to reports, increased global warming has caused the temperature of land and oceans to rise, and heavy precipitation or drought in many areas. The use of resources is increasing in those countries where the population is increasing tremendously [2].

Consequently, many firms are considering environmental protection as their social responsibility because of climate change and environmental risks are now becoming challenging. The first reason is that people are not showing responsibility and are not more concerned about environmental risks. In general, people are also unable to realize how their attitudes and behaviours lead to environmental problems [3,4]. The second reason is that due to the scientific complexity of the environmental problems it is difficult for a layperson to understand them with limited knowledge of mathematics, physics, etc., [5]. Third, it is observed that the culture and concepts of people related to the environment and climate change are the results of their sociocultural beliefs and values [6,7,8,9]. Human engagement and commitment towards environmentally friendly products increases through green marketing [10].

The concept of “green marketing” is gaining an important position on a global scale. Because of its strong connection to the cause of preserving the natural world, “green” advertising is often regarded as an effective marketing tactic that can be applied to the promotion of services, goods, and business concepts [11]. Recent increases in green customers have created a new market opportunity for the global economy. Scholars have been interested in green marketing and techniques for preserving the natural environment since the 1980s. Since the early 1990s, green marketing, and associated concepts have grown in popularity [12,13].

Due to advancements in environmental, scientific, and networking technologies, such as the world wide web, as well as increased public awareness of and concern with ecological challenges [14], such as the progressively increasing population and the worldwide temperature alteration, it is more important than ever to understand green purchase intention [15].

To deal with the growing environmental concerns it is very significant for marketers to investigate the aspects that influence consumer views and purchase decisions regarding a company’s offerings [16]. Values, trust/information, requirements and inspirations, attitudes, and socioeconomic factors are some of the aspects to consider [17]. Moreover, several mediating factors, such as eco-labels and customer response, impact customers’ willingness to spend extra for environmentally friendly products [18,19].

Although most buyers incline toward an environmentally better product over a substandard one in terms of the environment [20] in any case, data suggest that consumers frequently will not pay more for an environmentally friendly product [21]. Oddly, and unfortunately, it has been noticed that consumers with a strong inclination toward environmental issues are not particularly interested in acquiring green services and products [22]. Customers may have concerns over the environmental responsibility of a company, the quality, affordability, and accessibility of green products and services, as well as the company’s determination and devotion to the environment [23]. In addition to this, maintaining some sort of credibility has emerged as one of the most critical aspects of green marketing. Customer trust level can be enhanced by reducing the perceived risk of consumers about green products and services as it ultimately assists in removing the consumer suspicion [24]. Furthermore, many green products and services are revolutionary, prompting individuals to upgrade their preferences [25].

Green marketing involves stakeholder evaluation to build a significant prolonged association with consumers while preserving, sustaining, and enriching the natural environment [26]. Organizations use green marketing for five purposes: (1) taking advantage of green opportunities; (2) strengthening brand image; (3) enhancing product value; (4) improving competitive advantage; and (5) adhering to environmental advancements [27].

A strong and favourable association was established between green purchase intention with a green price, eco-friendly packaging, and advertisement regarding environmental concerns [28].

The findings of this study will assist marketers in designing a green marketing model to enhance green buying behaviour by investigating the key elements: ”Eco-labelling, green packaging and branding, green products, premium and pricing, green brand image, and customer beliefs towards the environment”. Customers’ perceptions of risk and value concerning products have been studied in the past, but none has explored them concerning green marketing and environmental challenges. As a result, this study fills a research gap. In addition, the concepts of “green marketing” and “consumer behaviour” in relation to the environment have not been examined sufficiently. In general, the discipline of marketing research has looked at both green marketing and consumer behaviour from a number of different perspectives [25,29,30,31,32]. Over time, consumer support for environmental preservation has intensified, leading to higher demand for green products [25,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. As a consequence of this, one of our primary study objectives was to fill in some of the existing knowledge gaps in the fields of green marketing and sustainable consumer attitudes. This research, which is based on our findings, provides recommendations on how these factors might be incorporated into the economy. This research looks at the following questions:

- Does eco-labelling have a significant impact on green purchase intention?

- Does green packaging and branding has a significant impact on green purchase intention?

- Do green products’ premium and pricing have a significant impact on green purchase intention?

- Does green brand image significantly mediate the relationship between eco-labelling and green purchase intention?

- Do green packaging and branding significantly mediate the relationship between eco-labelling and green purchase intention?

- Do green products, premium, and pricing significantly mediate the relationship between eco-labelling and green purchase intention?

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, there has been an increasing amount of research that suggests that the environmental sustainability holistic approach is associated with improved corporate commercial success [40]. Concerns about environmental degradation in society have increased competitive pressure and introduced new obstacles for businesses to overcome [41,42]. The worldwide living environment has worsened in recent years as a result of population increase and to meet consumer expectations. Consumer lifestyle and behaviour are linked to environmental system destruction. By gradually raising environmental consciousness and environmental preservation, people have participated in the formation of corporations that promote the ecosystem and environmental standards to avert irreversible environmental devastation by means of restrictions placed on international trade [43]. To maintain sustainable development over the long term, it is currently advised that businesses engage in activities such as paying attention to the significance of environmentally friendly products and environmentally responsible consumption. Whether a person is acting as a customer or a company owner, the natural environment has emerged as a topic of concern that is both relevant and essential [44]. As traditional marketing overemphasizes consumer requirements while ignoring social welfare and environmental problems, this issue has permeated all aspects of companies, affecting marketing and resulting in the development of the concept of green marketing [45].

During the course of the last few decades, environmental issues have evolved into a component of a company’s responsible and sustainable approach to conducting business. Additionally, environmental concerns have become a competitive possibility for social entrepreneurship and growth [46]. This idea represents the entrepreneurial company’s voluntary commitment to contributing to a greener planet and better people. It also describes the firm’s dedication to improving people’s lives. Environmental entrepreneurship and green marketing are two terms that have recently gained popularity, reflecting the public’s growing concern for the ways in which new businesses’ resources and skills affect the environment. Consequently, corporate initiatives that benefit the environment may result in increased commercial competitive advantages [47,48]. Green marketing is a set of actions that aim to ensure that the product exchange, which is the most essential component of marketing, has the smallest potential negative effect on the environment [49]. A “holistic management strategy that recognises, predicts, and serves the requirements of customers and enterprises effectively and sustainably” is what Peattie calls “green marketing” [50]. However, other sources claim that a more comprehensive definition of green marketing is based on activities such as the early phases of planning, executing, and controlling the growth, product pricing, and advertising, as well as manufacturing and distribution of products in a way that fits the requirements of meeting consumer wants while also accomplishing the corporation’s goals, and connecting these procedures to the environment. In other words, green marketing is a marketing strategy that aims to minimise the negative impact of a company’s operations on the environment [51].

At the core of strategic green marketing initiatives is a sense of social responsibility and a willingness to align marketing efforts with the expectations of both existing stakeholders and those who may emerge in the future. Sustainable marketing decisions result in long-term, corporate-wide environmental sustainability efforts [52]. A green marketing plan entails a shift in the customer–firm relationship. Firms must create both the functional and emotional qualities of a product to suit the demands of ecological customers. The majority of environmental issues include people’s environmentally friendly demands, which differ from a traditional marketing plan. Green marketing is considered a proactive approach as well as a long-term sustainable goal of the firm [53]. The main goal of green marketing is to gain a competitive edge by strategically placing items in the minds of customers. To accomplish this, all stakeholders in the value chain must be aligned with the green marketing objectives. This involves collaboration and environmental awareness from all concerned parties. “Market segmentation, green product creation, green positioning, green price determination, green logistics, sufficient residual management, green communication, green partnership development, and having an adjusted marketing mix” are some of the most important aspects of a green marketing strategy [54,55]. A firm must complete its homework and be clear on what it should do when developing a green marketing plan to get a competitive advantage [56]. This is an important consideration since accomplishing corporate goals includes more than just profit, they also entail making a good contribution to the environment. In order to maximize the advantages of green marketing, a marketing strategy needs to address some essential areas of importance, such as demographic segmentation, developing sustainable products, green positioning, setting green prices, or using green supply chain management, treatment and disposal management, launching green advertisements, solidifying green partnerships, and having the adequate green market [57].

Eco-labelling affects consumer behaviour since it reveals environmental concerns and product attributes [58]. It provides environmental product information to corporate users and consumers. Eco-labelling helps formulate environmental regulations and encourages ecologically sustainable product and service use. In addition to this, it is compatible with the multi-stakeholder policy as well as the related framework [59]. Eco-labelling has led to customer confusion, making it difficult to forecast product environmental quality [60]. The environmental effect of a product is a key part of its life cycle and an accreditation criterium. Eco-labels let consumers choose items and services with the minimal environmental effect over time. This cycle begins with raw material gathering and ends with disposal [61].

In the present body of research, a variety of corporate strategies and objectives about eco-labelling for items that are already labelled as well as those that are not labelled have been investigated [62]. Also, the competitiveness of products with eco-labels has been looked into again. Also, the idea of eco-labelling has been brought up in the recent research on green technology investment that has been published. For the purpose of eco-labelling, for instance, academics have concentrated their attention on investment, environmental quality behaviour, and price competitiveness. Eco-labelling has been identified as a significant instrument for reducing investment in low-quality products, and it has been found that businesses producing low-quality goods face intense competition. As a result, these businesses are able to improve their productivity through the application of eco-labelling [63]. Therefore, this study deduced the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Eco-labelling has a positive and significant impact on green purchase intention.

Green packaging, also referred to as sustainable packaging or eco-friendly packaging, is fully comprised of naturally occurring substances, can be reused or recycled and is prone to degradation, and encourages environmental sustainability during its whole lifespan. In addition, green packaging is safe and good for the environment as well as the health of people and animals [64]. However, consumers are becoming more conscious of green packaging and branding as a result of rising environmental concerns. Usually, brands influence customer perceptions of green products, as a successful green position requires brand distinctiveness and a unique selling point to succeed. According to recent research, products with no green features and attributes have less commercial success [65,66]. Customers will recognise a firm as a “sustainable brand” if it effectively conveys the distinctive green value it creates via its environmentally friendly offerings [67,68]. According to studies, green positioning is also crucial to the success of green branding initiatives [69]. There is a favourable correlation between the green attributes of the product and green purchasing intentions, according to previous studies on green products and environment-related activities. Another study revealed that consumers in Europe have a favourable attitude towards eco-branded items [70,71]. As a consequence of this, the second hypothesis can be formulated in the following way:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Green packaging and branding has a positive and significant impact on green purchase intention.

Customer investment in renewable energy is facilitated by the concept of “green pricing”. Customers respond well to premium pricing tactics in several regions. The quality of items with green premium pricing has also been proven to be greater [72]. Furthermore, research have shown that the majority of consumers are prepared to pay a premium for already available ecologically friendly items [73]. According to estimates, customers are more likely to participate in green pricing systems when green energy sources have fewer negative side effects, create more jobs, and provide financial incentives such as tax credits [74]. Furthermore, a well-designed environmental regulatory pricing plan encourages green activities, giving businesses a competitive edge. Product production and price strategies have a direct influence on a company’s profitability; hence, using the right pricing strategy while keeping the environment in mind may help a company succeed [75]. The green price of items is determined by several components. Consumer involvement rates are significantly influenced by green pricing and associated initiatives [76]. Similarly, a favourable correlation exists between the desire to engage in green purchasing behaviour and the attitude towards buying green items [77]. As a result, this research indicates that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Green products, premium, and pricing has a positive and significant impact on green purchase intention.

Some other authors also define “green brand image” is “a specific group of ideas, thoughts, and apprehensions about a brand in the minds of customers that are tied to sustainability and eco-friendly concerns” [78]. The image of the green brand is a subset of the overall brand image. When a company promises to offer environmentally friendly items, current quality perceptions in the minds of consumers may help to boost a greener brand image [79]. According to the findings of another study, the results of green marketing are strongly linked to the creation of a favourable brand image for environmentally friendly products. Furthermore, the study found that customer identity, in conjunction with product excellence and corporate and social responsibility viewpoints, has a significant impact on customers’ intentions to use environmentally friendly brand products [80]. According to Mourad (2012), green brand image has a positive influence on the selection of environmentally friendly brands. This indicates that a brand image that is environmentally friendly has an effect on the reputation of the firm, and a brand image that is positive enhances the possibility that consumers would adopt environmentally friendly goods [81]. The development of a strong marketing strategy is the first step in achieving success in expanding a company’s customer base and keeping existing customers committed to its offerings. People tend to act in a manner that is widely acceptable in society and are drawn to things that are already well-known, as suggested by the social cognitive theory. To clarify, people’s attitudes and perceptions of a brand play a crucial role in their decision to buy, how they behave after they do so, and how they treat the brand overall [82]. Therefore, it is referred to as:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Green brand image significantly mediates the relationship between eco-labelling and green purchase intention.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Green brand image significantly mediates the relationship between green packaging and branding and green purchase intention.

Trust may be measured by the degree to which an individual believes the product will live up to their expectations. Trust in the brand is a major factor in determining loyal customer behaviour over time [83]. As a result, consumer trust has an impact on customer intent to buy [84]. Literature from the past suggests that consumer intents to purchase are affected by buyer trust. Consumers’ purchasing intentions are influenced by their level of confidence in the company. This has been proven in different research [85]. Consumers’ propensity to spend more for eco-friendly goods varies not just by product category but also by the perceived value added. Consumers are prepared to pay a premium for eco-friendly goods, albeit the exact amount they are ready to spend varies by product category and savings expected [86]. Another study on hybrid cars seems to support the findings that consumers are willing to pay a premium for an environmentally friendly vehicle, despite the fact that this premium is relatively low and is influenced by the likelihood of a return on investment [87]. Therefore, the sixth hypothesis is written as follows:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Green brand image significantly mediates the relationship between green products, premium, and pricing and green purchase intention.

Environmental issues and concerns affect all businesses and individuals across the world [88]. Consumers are concerned about the environment, and as a result, their purchasing habits have gradually altered to support the preservation of the environment [89]. Because people are worried about the environment, their shopping behaviours have steadily shifted to reflect their desire to contribute to the protection of the environment in some way [90]. Creating a value for the environment is one of the behaviours that is significant [91]. On the other hand, there is the viewpoint that consumers who are concerned about the environment do not always act in a way that is beneficial to the environment. According to the findings of an empirical study, only a tiny fraction of consumers have shown an interest in recycling goods, are concerned about pollution, and are willing to pay extra for environmentally friendly products [92]. Therefore, the seventh and eight hypotheses state that:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Customer beliefs towards the environment significantly mediate the relationship between eco-labelling and green purchase intention.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Customer beliefs towards the environment significantly mediate the relationship between green packaging and branding and green purchase intention.

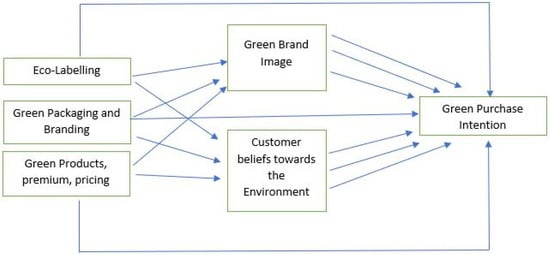

The “Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA)” explains that human conduct is impacted by a person’s ideas and attitudes. The subjective norm is the second most significant predictor of behavioural intention, but attitude is by far the most important [93]. Another study was conducted in 1980 by Ajzen and Fishbein and found that the majority of human behaviour can be predicted from the individual’s purpose. Behavioural purpose depends on attitude and perceived norms [94]. Figure 1 represents the framework of the study. Customers’ views towards hotel green activities were impacted by their behavioural beliefs in environmental conservation, according to Han, Hsu, and Sheu (2010). They demonstrated that behavioural beliefs influenced their attitudes toward environmental conservation [95]. Following is a hypothesis that has been developed on the basis of these discussions:

Figure 1.

Framework of the study.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Customer beliefs towards the environment significantly mediate the relationship between green products, premium, and pricing and green purchase intention.

3. Methods and Materials

The current study is non-contrived quantitative research. Individuals are the unit of analysis; targeted respondents are addressed individually. Each statement is solicited to elicit the individual’s perception of it. This study’s demographic covers all customers who buy green products from hypermarkets or online platforms in Pakistan. Customers who fall into this category prefer to do their shopping at large shopping malls or shopping centres because these establishments stock a greater variety of environmentally friendly goods and services. Examples of these goods and services include green electronic devices and gadgets, green packaged goods, basic commodities, and a variety of environmentally friendly products. However, the exact number of consumers is unclear because there is no method to measure how many individuals enter these malls or buy green products online [81]. It would be best to conduct the survey on the whole population, but since the population that was being studied was unknown, it was not practicable to include the full population in the survey. As a consequence of this, the convenience sample method was used in this research, and the participants were selected on the basis of the ease with which they could be contacted and their proximity to the researcher [96].

A multistage random sampling technique was used to study so that it provided more authentic and clear results. Due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, the collection of data was a major problem. Customers who purchase green products were unable to physically respond to questions and provide their answers. Self-administered questionnaires were sent to customers through the Internet. A total of 780 surveys were circulated, with 450 completely returned (57.6% response rate). These questionnaires were distributed and collected during January 2022–March 2022.

The extensive and comprehensive research questionnaire was designed to collect the primary data; the questionnaire was used to determine all the constructs of the study. Items of the “Eco-Labeling (EL), Green Packaging and Branding (GPB), Green Products, Premium, and Pricing (GPPP), and Consumer Beliefs towards the Environment (CBTE)” are adapted from Shabbir and colleagues [97]. Green Purchase Intentions (GPI) are adapted from Chen and Chang [98]. Whereas items of Green Brand Image (GBI) are adapted from Doszhanov [99]. The respondents’ responses were recorded and elicited using a Likert scale. A measuring scale (ranging from 1–5) was used to assess respondents’ degree of agreement with the individual question statements. SPSS version 23 and Smart PLS version 3.3 were used in the processing and analysis of the data, respectively. The coding of the data, the cleaning of the data, and the screening of the data were all performed via SPSS. In a related manner, SPSS was used in order to analyse the demographic characteristics as well as the descriptive analysis. The evaluation of measured and predicted associations was accomplished with the help of Smart PLS 3.0.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Demographics

Demographic percentages and frequencies, as well as histograms, are examined because the graphical depiction of facts improves clarity and significance. The Table 1 reflects the demographic details of the respondents (n = 450).

Table 1.

Demographics statistics of the respondents.

Of the respondents, 54.6% were male and 45.3% were female. Similarly, 37.5% of the respondent belonged to the 20–30 age group. The second major group was 31–40, including 24.4% of the respondents. The third dominant age group was 41–50, having 20.4% of the respondents; 9.7% and 7.7% of respondents belonged to the 20 or below and 50 or above categories, respectively. The majority of the respondents have completed their education up to the Bachelor level, i.e., 46.6%. Whereas 21.1% of the respondents have a degree of the Master’s program and 11.1% of the responders have undertaken an Mphil program. The demographic data aids in interpreting the research findings and better understanding the characteristics of the audience.

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

The first approach in evaluating a measurement model is measuring its reliability. The reliability and validity are measured using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability to measure the measurement model’s internal consistency. The level of internal consistency is higher when the value is closer to 1 and above [100]. Composite reliability is believed to be a preferable way to assess internal consistency, with values larger than 0.7 being deemed significant. Table 2 demonstrates that all reflective constructs have Cronbach alpha values of more than 0.7, and the composite reliability of all reflective constructs is also more than 0.7. This means that the construct is internally consistent. It shows that all of the indicators for each construct are consistent in their measurement of that construct. The fact that the estimated values of AVE are higher than 0.50 indicates that the construct represents greater than 50% of the variance of the indicator [101]. AVE values below 0.50 indicate that there are more errors in the indicators, values of AVE greater than 0.50 represent that there are fewer errors. AVE values in Table 2 are above the acceptance level of 0.50.

Table 2.

Construct reliability and validity.

The term, discriminant validity, refers to how distinct a construct is from any other construct in the analysis. In this study, discriminant validity is assessed with the help of the HTMT ratio [102,103]. Values of the HTMT ratio between the two constructs that are less than 0.9 are considered important for established discriminant validity. Table 3 depicts that all the values of the construct are in the optimum range and less than 0.9.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity–HTMT ratio.

4.3. Structural Model Assessment

VIF values are examined in the initial phase of structural model evaluation to review collinearity issues. VIF values in this study ranged from 1.872 to 2.427, indicating that there is no collinearity. Path coefficients are calculated in the second step to analyse the significance of the relationship. In the structural model, the path coefficient is the coefficient linking construct. It denotes the strength of the relationship or represents the significance of the relationship. It has a value between −1 and +1. A value closer to +1 means that the relationship is strong and positive, whereas a value closer to −1 means that the relationship is strong and negative [104]. The p-value and t-value for each path coefficient are used to determine their significance. We took 1.96 (significance level 5%) as the significance level for the t-value, and 0.05 (significance level 5%) as the significance level for the p-value. This means that all t-value values less than 1.96 are not recognized as significant, however values greater than 0.05 are recognized as non-significant. Table 4 represents the significance of the path coefficients of all hypothesized relationships of the study.

Table 4.

Significance of path coefficients.

The hypothesized relationship between Eco-Labelling (EL) → Green Purchase Intentions (GPI) has a path coefficient value of 0.131, whereas Green Packaging and Branding (GPB) → Green Purchase Intentions (GPI) has a path coefficient value of 0.281. Green Products, Premium, and Pricing (GPPP) → Green Purchase Intentions (GPI) have the highest value of 0.308. The t statistics for Eco-Labeling (EL) → Green purchase intentions (GPI) is 2.317 (t > 1.96), which is greater than the significance threshold, and the p-value of this relationship is likewise significant (p = 0.000). The t statistics for the relationship Green Packaging and Branding (GPB) → Green purchase intentions (GPI) is 4.654 (t > 1.96), more than the significance threshold, and the p-value of this relationship is likewise significant (p = 0.000). Similarly, t statistics and p-value for the relationship of Green Products, Premium, and Pricing (GPPP)→Green purchase intentions (GPI) are 6.144 (t > 1.96), and 0.000 respectively. Figure 2 represents the SEM model of the study.

Figure 2.

SEM model of the study.

The next step in evaluating a structural model is to analyse the coefficient of determination (R2 value). The coefficient of determination is used to calculate the amount of variance explained by the exogenous variable in the endogenous variable. R squared has a range of 0 to 1. An R2 value of 0.75, 0.50, or 0.25 can be represented as strong, moderate, or weak impact on the dependent variable. The R-squared value of the GPI is 0.678, indicating a moderate to strong influence, whereas the value of the GBI is 0.477, indicating a weak to moderate impact. CBTE is considered as a moderate impact since CBTE has an R2 value of 0.527. As the values of R squared and R squared adjusted differ less, the model is deemed parsimonious. Table 5 shows the R2 values of the study.

Table 5.

Coefficient of determination (R2 value).

Mediation Analysis

There are a total of six indirect effects in this study, reflected in Table 6. The relationship between EL → GBI → GPI has path coefficient value of 0.257 and t-value is 3.622; according to the significance level (t > 1.96). The relationship between GPB → GBI → GPI is also significant with value of 3.785; according to the significance level (t > 1.96). Similarly, relationship numbers 3, 5, and 6 are significant relationships as they have t-values that are more than the minimum threshold (t > 1.96), i.e., 4.723, 3.411, and 7.688, respectively. On the other hand, the relationship between EL → CBTE → GPI has a path coefficient value of 0.021, and a value of 0.337 which is less than the minimum acceptable criteria (t < 1.96). So, this path relationship is not considered a significant relationship. Hence, the specific indirect relationships between the five paths are considered significant.

Table 6.

Specific indirect effects.

5. Discussion

The current study’s findings depicted that all the defined constructs: eco-labelling, green packaging and branding, and green products, premium and pricing have a positive relationship with green purchase intention. The relationships between eco-labelling, green packaging and branding, and green products, premium and pricing, and green purchase intention were significant.

One of the findings of the study is that eco-labelling has an impact on green purchase intention and this result is supported by [105]. This past study investigated that eco-labelling has a relatively significant impact on consumers’ purchasing intentions when compared with other product attributes such as brand name. Eco-labelling has a significant and positive impact on consumer behaviour towards the environment [106].

The current study also showed that green packaging and branding have a significant impact on green purchase intention. This is reinforced by a massive amount of prior research on how brands may affect purchasers’ views about purchasing green goods, since an effective green stance makes a brand distinctive. It has also been suggested that non-green products have smaller sales growth [107]. Furthermore, scholars have claimed that environmentally friendly positioning is critical to the successful implementation of green branding strategies [108]. The relevance and behaviour of environmental products and their properties has the subject of numerous research. Consumers in European countries have shown supportive attitudes toward environmental products [109].

The finding of this study revealed that green products, premium and pricing have a significant impact on green purchase intention. Through market analysis, it has been estimated that in the marketplace a number of buyers are willing to pay higher prices for green services/products. Green pricing gives consumers more options for renewable energy investment. Consumers respond positively to premium pricing techniques in several countries. Additionally, it has been shown that goods that command a higher price just because they are greener are of higher quality [110]. Furthermore, a comprehensible environmental pricing approach encourages green activities, giving businesses a competitive advantage. The profit margins of a product are directly influenced by its production and pricing techniques [111].

In the present research, it has been explored whether or not a green brand image acts as a mediator between eco-labelling and the desire to make environmentally conscious purchases. In previous studies, it was found that companies’ greenwashing behaviour not only has a direct negative impact on their customers’ green purchasing intention, but it also has an indirect negative impact on it through their green brand image and customer trust. In other words, greenwashing has a double negative effect [112]. The key contribution of the current study relates to the mediating role of green brand image on the eco-labelling–green purchase intention relationship. In other words, we can say that a green brand image successfully allows firms to increase green purchases by using the tool of eco-labelling.

The finding of this study also revealed that green brand image mediates the relationship between green packaging and branding and green purchase intention. A recent study explored that green packaging design appears to be a powerful determinant of green trust, which increases green brand engagement [113]. Another study revealed that the green brand image and green brand behaviour have a favourable impact on green brand engagement [114]. The key contribution of the current study relates to the mediating role of green brand image on the green packaging and branding–green purchase intention relationship. In other words, we can say that green brand image successfully allows firms to increase green purchases by employing green packaging and branding and should avoid excessive packaging of the product as excessive packaging of the product harms green brand image and the green brand attitude of consumers [114,115].

Green brand image mediates the link between green goods, premium, and price, and green buying intention. Green pricing and related measures increase customer participation, previous research found [116]. Green goods, premiums, and price influence customer environmental attitudes. This study also showed that purchasers assume some of the amount they spend for green items goes toward environmental concerns. Also, the fact that purchasers were prepared to pay extra for green services/products, underlines the significance of green goods’ eco-image, and calls for increased green product marketing awareness [106]. The present study’s primary contribution is the mediating influence of green brand image on green goods, premium and pricing–green buying intention. In other words, we can say that green brand image successfully allows firms to increase green purchases by employing the strategy of green products, premium and pricing as consumers pay more for the environmentally friendly product compared with an environmentally inferior product.

The finding of the current study revealed that customer beliefs towards the environment significantly mediate the relationship between eco-labelling and green purchase intention. Past research investigated that eco-labelling has a positive and significant impact on green purchase intention [106]. Eco-labelling affects consumer behaviour because it transmits environmental and product quality information [117]. Customer perceptions about the environment mediate the eco-labelling–green purchasing intention connection. In other words, we can say that customers’ belief towards the environment successfully allows firms to increase green purchases by using the tool of eco-labelling.

Customers’ environmental sentiments strongly moderate the association between green packaging and branding and green purchasing intention. Past research concluded that due to the greater demand of stakeholders and high consumer pressure on the preservation of the natural environment, many companies have moved far away from just addressing the environmental regulatory challenges by introducing alternatives of inferior products. Some companies have created ecologically friendly packaging or support cause-related campaigns (Greenhouse Challenge (2005)). The major contribution of the present research is the mediation influence of consumer environmental beliefs on green packaging and branding–green purchasing intention. In other words, we can say that customers’ beliefs towards the environment successfully allow firms to increase green purchases by employing green packaging and branding as customers demand companies to preserve the natural environment by the environmentally friendly packaging of products [118].

The results of this study show that customer beliefs towards the environment significantly mediates the relationship between green products, premium, and pricing, and green purchase intention. A recent study reported that due to the increased customer concern for the environment, consumers are willing to pay more, even if they have low motivation for sustainable development and a low eco-literacy rate [119]. Green products, premium, and pricing have a positive and significant impact on customer beliefs toward the environment [106].

6. Conclusions

The present research investigated how factors such as eco-labelling, green packaging and branding, and green product, premium, and price affect consumers’ propensity to make environmentally conscious purchases. Eco-labelling, green packaging and branding, and green product, premium, and price were all shown to have a substantial and favourable effect on customers’ intentions to make green purchases. This research also looked at the role of green brand image and consumer perceptions about the environment as mediators between various marketing strategies and green purchase intentions. Several green marketing strategies, including eco-labelling, green packaging and branding, and green product, premium, and price, were emphasised and proposed in this research. This research recommended that organisations should take into account the results of this research when developing environmentally friendly strategies and the impact they have on producing value in contemporary business contexts. Policymakers in charge of developing and enforcing marketing strategies and rules benefited from the research since it provided new data and pointed them in the right direction.

7. Implications

People are becoming more aware of the importance of maintaining a cleaner and safer environment. We all want clean air and water, better waste management, and more efficient use of natural resources. However, despite some improvements, all of these are under significant stress in some regions. Commercial products play a significant role in these environmental issues and have a variety of negative effects on people’s health. Approximately 100,000 chemicals are utilized in the production process; all are unregulated and can contain hazardous, allergic, and carcinogenic substances.

The first implication of this study is that it is giving some important suggestions to businesses and policymakers. As the results of this study revealed that eco-labelling, green packaging and branding, and green product, premium and pricing have a significant influence on the consumer’s intention to purchase green products. Therefore, firms should improve their green marketing for example by using the tool of eco-labelling. A logo conveying the message of natural environmental protection should be displayed prominently on the front of the packaging or any appliances. Packaging of the products should be environmentally friendly and avoid excessive packaging using paper and plastic. For branding their products, companies should use the environmental aspects of the products. Firms should avoid non-sustainable methods while manufacturing and packaging their products. Firms should design products that have little or no negative impact on the natural environment during their entire lifespan and even after they are no longer in use. For environmental-friendly products, people tend to pay more compared with environmentally inferior products. As a result, customers are more likely to trust the business, perceive green activities by firms, and be more eager to buy the company’s environmentally friendly products.

The second implication of this study is that this paper proposed a new framework of different green marketing approaches in compliance with green brand image and customers’ beliefs towards the environment to help companies increase the green purchase intentions of consumers for their products. This research highlighted the value and role of green brand image and customers’ beliefs towards the environment in terms of studying the green purchase intentions of the consumers. Previous studies on green marketing have looked at how various green marketing strategies affect consumers’ perceptions of the environment and their intentions to buy green goods [99,106]. However, the impact of green marketing strategies on green purchase intentions has not been investigated through the lens of mediating variables like green brand image and consumer environmentalist attitudes. This study found that eco-labelling, green packaging and branding, and green product, premium, and price may help businesses boost sales of environmentally friendly offerings by appealing to consumers’ green brand image and their environmental consciousness.

8. Limitations and Future Directions

The present study, like all others, includes flaws that might be dealt with in future research studies. To begin with, the research failed to give even the barest scraps of data about any one firm, product, or sector. As green products are so diverse in nature, it is difficult to understand how these green marketing approaches will work and support the purchase intentions of consumers for certain green products. Future research can examine the impact of green marketing approaches on the green purchase intentions of consumers for specific brands or products. Second, this study examined the green purchase intention of hypermarket consumers and those who buy from online platforms. Future research should aim to study the consumer’s green purchase intentions at different marketplaces of in a specific country to see if there is any impact between the factors that have been specified in the current study. Third, to further explore the concept of green marketing and its impact on consumer green purchase intention, there are many dimensions in this field that need to be addressed in future studies, for example, how the green marketing concept can assist people to engage in the protection of the natural environment by reducing the disposal of plastic waste and preserving natural resources. Future scholars can investigate which methods and techniques companies should use for the manufacturing and designing of green products so that they can control waste disposal as not to pollute the natural environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.U.M.; Formal analysis, S.A.M.; Funding acquisition, S.A. (Szakács Attila); Methodology, S.A. (Sumaira Aslam); Writing—review & editing, E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the respondents of the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The publication of this study was supported by the EU-funded Hungarian grant EFOP-3.6.3.-VEKOP-16-2017-00007, for the project entitled “From Talent to Young Researchers”—Supporting the Career-developing Activities of Researchers in Higher Education.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- He, Q.; Silliman, B.R. Climate Change, Human Impacts, and Coastal Ecosystems in the Anthropocene. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R1021–R1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein Goldewijk, K.; Beusen, A.; Janssen, P. Long-Term Dynamic Modeling of Global Population and Built-up Area in a Spatially Explicit Way: HYDE 3.1. Holocene 2010, 20, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.A.; Kates, R.W.; Parris, T.M. Do Global Attitudes and Behaviors Support Sustainable Development? Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2005, 47, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijnders, A.L.; Midden, C.J.; Wilke, H.A. Communications About Environmental Risks and Risk-Reducing Behavior: The Impact of Fear on Information Processing 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 31, 754–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J.D.; Sweeney, L.B. Understanding Public Complacency about Climate Change: Adults’ Mental Models of Climate Change Violate Conservation of Matter. Clim. Change 2007, 80, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothmann, T.; Patt, A. Adaptive Capacity and Human Cognition: The Process of Individual Adaptation to Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Storch, H.; Krauss, W. Culture Contributes to Perceptions of Climate Change. Nieman Rep. 2005, 59, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Weingart, P.; Engels, A.; Pansegrau, P. Risks of Communication: Discourses on Climate Change in Science, Politics, and the Mass Media. Public Underst. Sci. 2000, 9, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. Behavioural Responses to Climate Change: Asymmetry of Intentions and Impacts. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groening, C.; Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q. Green Marketing Consumer-Level Theory Review: A Compendium of Applied Theories and Further Research Directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1848–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Z.; Ali, N.A. The Impact of Green Marketing Strategy on the Firm’s Performance in Malaysia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.; Lau, L.B. Antecedents of Green Purchases: A Survey in China. J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Fotiadis, T.A.; Christodoulides, P.; Spyropoulou, S.; Katsikeas, C.S. Environmentally Friendly Export Business Strategy: Its Determinants and Effects on Competitive Advantage and Performance. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. The Growing Level of Environmental Awareness. The Huffington Post, 29 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Balderjahn, I. Personality Variables and Environmental Attitudes as Predictors of Ecologically Responsible Consumption Patterns. J. Bus. Res. 1988, 17, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatis, S.P.; Pollard, M.; East, R.; Tsogas, M.H. Green Marketing and Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Cross-Market Examination. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S. Understanding Green Consumer Behaviour: A Qualitative Cognitive Approach; Consumer Research and Policy Series; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. The Determinants of an Environmentally Responsive Firm: An Empirical Approach. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1996, 30, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straughan, R.D.; Roberts, J.A. Environmental Segmentation Alternatives: A Look at Green Consumer Behavior in the New Millennium. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 6, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing Better at Doing Good: When, Why, and How Consumers Respond to Corporate Social Initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsato, R.J. Competitive Environmental Strategies: When Does It Pay to Be Green? Calif. Manag. Rev. 2006, 48, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Lee, J.W.C.; Mohamad, O. Green Product Purchase Intention: Some Insights from a Developing Country. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.R.; Smith, J.S.; Andrews, D.; Cronin, J.J., Jr. Against the Green: A Multi-Method Examination of the Barriers to Green Consumption. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Gokarn, S. Green Marketing: A Means for Sustainable Development. J. Arts Sci. Commer. 2013, 4, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Peattie, K.; Crane, A. Green Marketing: Legend, Myth, Farce or Prophesy? Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2005, 8, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pride, S.R.; Flekkøy, E.G.; Aursjø, O. Seismic Stimulation for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Geophysics 2008, 73, O23–O35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The Drivers of Green Brand Equity: Green Brand Image, Green Satisfaction, and Green Trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, N. Impact of Green Marketing on Consumer Purchase Intention. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamossy, G.J.; Solomon, M.R. Consumer Behaviour: A European Perspective; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Farzin, A.; Yousefi, S.; Amieheidari, S.; Noruzi, A. Effect of Green Marketing Instruments and Behavior Processes of Consumers on Purchase and Use of E-Books. Webology 2020, 17, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, S.; John, S. Consumer Behaviour in Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P. Green Marketing Innovations in Small Indian Firms. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 11, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Simintiras, A.C. The Impact of Green Product Lines on the Environment: Does What They Know Affect How They Feel? Mark. Intell. Plan. 1995, 13, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J. The New Rules of Green Marketing: Strategies, Tools, and Inspiration for Sustainable Branding; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ottman, J.; Books, N.B. Green Marketing: Opportunity for Innovation. J. Sustain. Prod. Des. 1998, 60, 136–667. [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky, M.J. An Introduction to Green Marketing. Electron. Green J. 1994, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, Y.; Iftikhar, B.; Nazir, M.N.; Kamran, H.W. Supply Chain Evolution and Green Supply Chain Perspective. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2016, 4, 716–724. [Google Scholar]

- Salzman, J. Informing the Green Consumer: The Debate over the Use and Abuse of Environmental Labels. J. Ind. Ecol. 1997, 1, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermerwe, S.; Oliff, M.D. Customers Drive Corporations. Long Range Plann. 1990, 23, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halme, M.; Korpela, M. Responsible Innovation Toward Sustainable Development in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Resource Perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 547–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersén, J.; Jansson, C.; Ljungkvist, T. Can Environmentally Oriented CEOs and Environmentally Friendly Suppliers Boost the Growth of Small Firms? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, A.; Adomako, S.; Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Owusu-Agyei, S.; Konadu, R. Environmental Sustainability Orientation, Competitive Strategy and Financial Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbulescu, A. Modeling the Impact of the Human Activity, Behavior and Decisions on the Environment. Marketing and Green Consumer (Special Issue). J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 204, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Ackerman, M.A.; Azzaro-Pantel, C. Extending the Scope of Eco-Labelling in the Food Industry to Drive Change beyond Sustainable Agriculture Practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 204, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abzari, M.; Safari Shad, F.; Abedi Sharbiyani, A.A.; Parvareshi Morad, A. Studying the Effect of Green Marketing Mix on Market Share Increase. Eur. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. Proc. 2013, 2, 641–653. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: Evolution of a Definitional Construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravcikova, D.; Krizanova, A.; Kliestikova, J.; Rypakova, M. Green Marketing as the Source of the Competitive Advantage of the Business. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, C. Ecopreneurship and Ecopreneurs: Limits, Trends and Characteristics. Sustainability 2017, 9, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Vocalelli, D. “Green Marketing”: An Analysis of Definitions, Strategy Steps, and Tools through a Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Ottman, J.; Polonsky, M.; Charter, M. Marketing and Sustainability. Available online: http://www.cfsd.org.uk/ (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Papadas, K.-K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M. Green Marketing Orientation: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, L.; Lisboa, A. Green Marketing and Green Brand—The Toyota Case. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 12, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, S.; Webster, J. Perceived Greenwashing: The Effects of Green Marketing on Environmental and Product Perceptions. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Guo, S.; Zhang, H. Coordinating a Green Agri-Food Supply Chain with Revenue-Sharing Contracts Considering Retailers’ Green Marketing Efforts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-K.; Wu, W.-Y.; Pham, T.-T. Examining the Moderating Effects of Green Marketing and Green Psychological Benefits on Customers’ Green Attitude, Value and Purchase Intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-H.; Lin, G.-Y.; Zheng, Y.-L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, P.-Z.; Su, Z.-C. Exploring the Effect of Starbucks’ Green Marketing on Consumers’ Purchase Decisions from Consumers’ Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Z. Joint Green Marketing Decision-Making of Green Supply Chain Considering Power Structure and Corporate Social Responsibility. Entropy 2021, 23, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okanović, A.; Ješić, J.; DJaković, V.; Vukadinović, S.; Andrejević Panić, A. Increasing University Competitiveness through Assessment of Green Content in Curriculum and Eco-Labeling in Higher Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, N.; Hussain, A.; Lohano, H.D. Eco-Labeling and Sustainability: A Case of Textile Industry in Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brécard, D. Consumer Misperception of Eco-Labels, Green Market Structure and Welfare. J. Regul. Econ. 2017, 51, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Lyon, T.P. Competing Environmental Labels. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2014, 23, 692–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukonza, C.; Hinson, R.E.; Adeola, O.; Adisa, I.; Mogaji, E.; Kirgiz, A.C. Green Marketing: An Introduction. In Green Marketing in Emerging Markets: Strategic and Operational Perspectives; Mukonza, C., Hinson, R.E., Adeola, O., Adisa, I., Mogaji, E., Kirgiz, A.C., Eds.; Palgrave Studies of Marketing in Emerging Economies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 3–14. ISBN 978-3-030-74065-8. [Google Scholar]

- Asha’ari, M.J.; Daud, S. The Effect of Green Growth Strategy on Corporate Sustainability Performance. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 8668–8674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, Z. Green Packaging Management of Logistics Enterprises. Phys. Procedia 2012, 24, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Sheng, G.; Peverelli, P.; Dai, J. Green Branding Effects on Consumer Response: Examining a Brand Stereotype-Based Mechanism. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 30, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenson, M.R.; Wells, W.D. Useful Correlates of Pro-Environmental Behavior. In Social Marketing; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-1-315-80579-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza Ibáñez, V.; Forcada Sainz, F.J. Green Branding Effects on Attitude: Functional versus Emotional Positioning Strategies. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2005, 23, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Lobo, A.; Leckie, C. Green Brand Benefits and Their Influence on Brand Loyalty. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2017, 35, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, H.; Wang, Y.; Yasmeen, H. Reinforcing Green Competitive Advantage through Green Production, Creativity and Green Brand Image: Implications for Cleaner Production in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Bilharz, M. Green Energy Market Development in Germany: Effective Public Policy and Emerging Customer Demand. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreen, N.; Purbey, S.; Sadarangani, P. Impact of Culture, Behavior and Gender on Green Purchase Intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiser, R.; Olson, S.; Bird, L.; Swezey, B. Utility Green Pricing Programs: A Statistical Analysis of Program Effectiveness. Energy Environ. 2005, 16, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülkü, M.A.; Hsuan, J. Towards Sustainable Consumption and Production: Competitive Pricing of Modular Products for Green Consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4230–4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.H.; Rishi, M. Increasing Consumer Participation Rates for Green Pricing Programs: A Choice Experiment for South Korea. Energy Econ. 2018, 74, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Sheu, J.-B. Environmental-Regulation Pricing Strategies for Green Supply Chain Management. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2009, 45, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Cao, H.; Zhu, G. Competitive Pricing and Innovation Investment Strategies of Green Products Considering Firms’ Farsightedness and Myopia. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2021, 28, 839–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Liu, Y.; Mo, Z. Moral Norm Is the Key: An Extension of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) on Chinese Consumers’ Green Purchase Intention. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 1823–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Khwaja, M.G.; Rashid, Y.; Turi, J.A.; Waheed, T. Green Brand Benefits and Brand Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Green Brand Image. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020953156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Kumar Dokania, A.; Swaroop Pathak, G. The Influence of Green Marketing Functions in Building Corporate Image: Evidences from Hospitality Industry in a Developing Nation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2178–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.; Hwang, Y.K.; Kim, E.Y. Green Marketing’ Functions in Building Corporate Image in the Retail Setting. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M.; Serag Eldin Ahmed, Y. Perception of Green Brand in an Emerging Innovative Market. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2012, 15, 514–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi Juwaheer, T.; Pudaruth, S.; Monique Emmanuelle Noyaux, M. Analysing the Impact of Green Marketing Strategies on Consumer Purchasing Patterns in Mauritius. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 8, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, D.P.; Febriani, R. Green Customer Behaviour: Impact of Green Brand Awareness to Green Trust. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1477, 72022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, D.P.; Syarifuddin, D. Store Image: Mediator of Social Responsibility and Customer Perceived Value to Customer Trust for Organic Products. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 288, 12045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Guo, R. The Effect of a Green Brand Story on Perceived Brand Authenticity and Brand Trust: The Role of Narrative Rhetoric. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yu, L. Differential Pricing Decision and Coordination of Green Electronic Products from the Perspective of Service Heterogeneity. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdenko, R.; Jensen, M.; Coelho, D. Pricing of Green Products: Premiums Paid, Consumer Characteristics and Incentives. Int. J. Bus. Mark. Decis. Sci. 2011, 4, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, I.; Karagouni, G.; Trigkas, M.; Platogianni, E. Green Marketing: The Case of Greece in Certified and Sustainably Managed Timber Products. EuroMed J. Bus. 2010, 5, 166–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuthnot, J. The Roles of Attitudinal and Personality Variables in the Prediction of Environmental Behavior and Knowledge. Environ. Behav. 1977, 9, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, M.; Bartikowski, B. Cultural and Identity Antecedents of Market Mavenism: Comparing Chinese at Home and Abroad. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, R.; Sultana, S.; Masud, M.M.; Jafrin, N.; Al-Mamun, A. Consumers’ Environmental Ethics, Willingness, and Green Consumerism between Lower and Higher Income Groups. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archodoulaki, V.-M.; Jones, M.P. Recycling Viability: A Matter of Numbers. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCaille, L. Theory of Reasoned Action. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 2231–2234. ISBN 978-3-030-39903-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Jaccard, J.; Davidson, A.R.; Ajzen, I.; Loken, B. Predicting and Understanding Family Planning Behaviors. In Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Green Hotel Choice: Testing the Effect of Environmental Friendly Activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.W. Convenience Sampling, Random Sampling, and Snowball Sampling: How Does Sampling Affect the Validity of Research? J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2015, 109, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M.S.; Bait Ali Sulaiman, M.A.; Hasan Al-Kumaim, N.; Mahmood, A.; Abbas, M. Green Marketing Approaches and Their Impact on Consumer Behavior towards the Environment—A Study from the UAE. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chang, C. Enhance Green Purchase Intentions: The Roles of Green Perceived Value, Green Perceived Risk, and Green Trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doszhanov, A.; Ahmad, Z.A. Customers’ Intention to Use Green Products: The Impact of Green Brand Dimensions and Green Perceived Value. SHS Web Conf. 2015, 18, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, E.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Brose, A.; Schmiedek, F.; Muthén, B. At the Frontiers of Modeling Intensive Longitudinal Data: Dynamic Structural Equation Models for the Affective Measurements from the COGITO Study. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2018, 53, 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4522-1744-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Cheah, J.-H. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling Using SmartPLS: A Software Review. J. Mark. Anal. 2019, 7, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.; Mena, J. An Assessment of the Use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing Research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammer, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. The Influence of Eco-Labelling on Consumer Behaviour–Results of a Discrete Choice Analysis for Washing Machines. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, M.N.; Aftab, H.; Martins, J.M.; Aslam, S.; Majeed, M.U.; Correia, A.B.; Rita, J.X. The Role of Intellectual Capital in Shaping Business Performance: Mediating Role of Innovation and Learning. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, J.M.; Aftab, H.; Mata, M.N.; Majeed, M.U.; Aslam, S.; Correia, A.B.; Mata, P.N. Assessing the Impact of Green Hiring on Sustainable Performance: Mediating Role of Green Performance Management and Compensation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meffert, H.; Kirchgeorg, M. Das Neue Leitbild Sustainable Development: Der Weg Ist Das Ziel; Manager-Magazin-Verl.-Ges.: Hamburg, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.; Li, J.; He, M.; Li, J.; Zhi, D.; Qin, F.; Zhang, C. Global Evolution of Research on Green Energy and Environmental Technologies:A Bibliometric Study. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swezey, B.G.; Bird, L. Utility Green Pricing Programs: What Defines Success? National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2001.

- Shi, D.; Zhang, W.; Zou, G.; Ping, J. Advertising and Pricing Strategies for the Manufacturer in the Presence of Brown and Green Products. Kybernetes 2021, 51, 1452–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Huang, A.-F.; Wang, T.-Y.; Chen, Y.-R. Greenwash and Green Purchase Behaviour: The Mediation of Green Brand Image and Green Brand Loyalty. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2020, 31, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-C.; Zhao, X. Exploring the Relationship of Green Packaging Design with Consumers’ Green Trust, and Green Brand Attachment. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdpitak, C.; Mekkham, W. The Mediating Roles of Green Brand Image and Attitude of Green Branding in the Relationship between Attachment of Green Branding and Excessive Product Packaging in Thai Sports Manufacturing Firms. J. Hum. Sport Exercise. 2019, 14, S2202–S2216. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Hung, S.-T.; Wang, T.-Y.; Huang, A.-F.; Liao, Y.-W. The Influence of Excessive Product Packaging on Green Brand Attachment: The Mediation Roles of Green Brand Attitude and Green Brand Image. Sustainability 2017, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Li, M.; Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J. Pricing Policies of Dual-Channel Green Supply Chain: Considering Government Subsidies and Consumers’ Dual Preferences. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, R.M.; Aftab, H.; Aslam, S.; Majeed, M.U.; Correia, A.B.; Qureshi, H.A.; Lucas, J.L. Empirical Investigation of Work-Related Social Media Usage and Social-Related Social Media Usage on Employees’ Work Performance. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhouse Challenge (2005) ‘The Challenge’—Google Search. Available online: https://www.google.com/search?q=Greenhouse+Challenge+%282005%29+%E2%80%98The+challenge%E2%80%99%2Candsxsrf=ALeKk022TmzZXX0Hv51aMyIOfFtvqeTeJg%3A1626078578985andei=cv3rYKvbO_afjLsPgoa6oA8andoq=Greenhouse+Challenge+%282005%29+%E2%80%98The+challenge%E2%80%99%2Candgs_lcp=Cgdnd3Mtd2l6EANKBAhBGABQ6ZoCWOmaAmCgpAJoAHACeACAAQCIAQCSAQCYAQOgAQGqAQdnd3Mtd2l6wAEBandsclient=gws-wizandved=0ahUKEwir3M7gjt3xAhX2D2MBHQKDDvQQ4dUDCA4anduact=5 (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Wei, S.; Ang, T.; Jancenelle, V.E. Willingness to Pay More for Green Products: The Interplay of Consumer Characteristics and Customer Participation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 45, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).