Abstract

Increasing concerns about the human impact on the environment are leading to new challenges for companies and their employees. Specifically, the food industry is facing the need to provide sustainable services, requiring a specialized and skilled workforce. This article presents a case study of an Italian sustainable Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) operating in the food sector in order to determine the drivers of working for this company, the key skills needed, and the Green Human Resource Management practices adopted. A total of 13 semi-structured interviews were conducted with employees and thematically analyzed. The findings showed that soft skills were perceived as more relevant than hard skills, although the food sector is characterized by high technical complexity and subjected to several national and international regulations. Moreover, the crucial role of organizational culture in determining the relevance of soft skills within the company and in fostering the implementation of the holacracy organizational management method emerged. Finally, by detecting the relevance recognized to values and soft skills during the recruitment and selection process, our findings provided some evidence of Green Human Resource Management in sustainable SMEs.

1. Introduction

In the present global scenario, the increase in environmental concerns is putting more and more pressure on societies, companies, and individuals [1,2], forcing them to change their way of thinking and acting in the short and long term.

Specifically, companies are increasingly expressing the need to move from a strategy usually focused on productivity, efficiency, and carelessness regarding the waste of resources to one able to consider the equitable distribution of resources in terms of internal and external sustainability [3,4].

The concept of sustainability refers to a type of sustainable development [4] that implies, according to the World Commission on Environment and Development, that the future needs of the new generation are not hindered or threatened by the needs of the present ones. The increasing destruction of natural ecosystems has pushed governments around the globe to establish laws and policies geared to promote sustainability and reduce negative environmental effects on natural resources [5,6].

Even though the need for urgent changes toward sustainability has been known for several years, green-oriented expedients, practices, and policies are sometimes just declared and not fully adopted. For this reason, it is essential to raise awareness of the topic in order to encourage its application within organizations and in everyone’s daily life.

Although most sustainability-related issues depend on decisions taken at a global legislative level, in order to achieve sustainable development, every society needs corporate contribution with an approach that is characterized by the realization of a compromise between the satisfaction of the needs of the organization’s stakeholders and the ability of the organization itself to satisfy their future demands [7].

In order to reach this compromise, companies should implement a strategy that can build synergies between economic wealth, social issues, and the maintenance of environmental health [8,9]. To this aim, it is relevant for organizations to adopt Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) to go “beyond pure profit-seeking that includes economic, social, and environmental concerns” [10] (p. 3) and to be able to define new competitive advantages [11,12]. Considering the different industry sectors, the food sector is particularly connected with CSR [13]. Moreover, taking into account the number of the current population, which is around 7.83 billion, as well as that of the future population, which is expected to increase, the importance of considering the food sector and its wastage, known as Food Loss and Waste (FLW), which can manifest differently concerning consequences such as high socioeconomic costs and environmental degradation, is clear [14,15,16]. This issue will be analyzed in the case study, as it is one of the main concerns of the company considered.

In order to be fully effective and perform strategically in their field, green firms can adopt the principles of Green Management (i.e., Environmental Management, EM [17]), namely a new management model that not only considers the needs of stakeholders but also takes into account social and environmental demands from a strategic point of view [12] by incorporating the environmental needs and strategies to the broader organizational ones [18].

The choice to adopt Green Management can lead to numerous benefits [19], such as cost saving, marketing opportunities, good corporate image, improved competitive position and performance, employee motivation, and the possibility to influence legislation toward environmental change, generating a continuous process of assessment and improvement [12,20,21,22].

The transition from a common organization to a green firm (i.e., firms that base their goals and values on sustainability issues, such as conservation, environmental welfare, ecological concerns, fair trade, equality, clean water, preservation of animal welfare, etc. [23]) requires some steps that can be summarized in three different stages of Green Management evolution [24,25]:

- Reactive: It is the first stage of Green Management, during which organizations start to face environmental legislation and regulation. In this phase, environmental awareness and authority begin to grow inside the company;

- Preventive: In this second stage, the organization starts to understand how to better manage resources in terms of sustainability and efficiency. During this phase, Green Management is integrated into the organization’s structure;

- Proactive: It is the third stage, during which CSR is fully integrated into the business strategy to create competitive advantages.

The classification just presented is the result of a series of previous studies [26,27,28,29], with concepts that were then re-adapted in subsequent and updated studies such as those considered in this article.

The extant literature shows that firms do not implement Green Management in the same way and with the same timing because they may present different peculiarities regarding their internal structure and the context in which they operate. Therefore, there may be companies whose characteristics do not fully fit into a single evolutionary stage and consequently stand between the two of them.

In order to be applied, Green Management needs the commitment of all members of the organization to perceive the organization itself as a community and to achieve long-term success while sustaining employees’ enthusiasm and problem-solving orientation [12].

Since managing an organization means, first of all, taking into account the human capital, it is important for a green firm to adopt Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) [30] together with a focus on green skills [31] and Green Leadership [32]. These aspects turn out to be fundamental in order to enhance employees’ commitment, develop skills through environmental training [33], and strengthen the culture and the organizational behaviors crucial for the company’s success in implementing environmental management initiatives [24,34].

Although the relevance of green skills has been recognized, it represents an underexplored topic, and, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of empirical studies analyzing the relevance of green skills for firms operating in different sectors and specifically for sustainable SMEs. Accordingly, this study contributes to filling this gap by answering a call for more research focused on green skills in specific sectors (e.g., waste management [31]). Furthermore, the literature analyzed green skills mainly from the technical side (i.e., green hard skills [35]), with few studies investigating Green Soft Skills [36,37,38]. For this reason, the present research will explore this aspect.

Additionally, there are few empirical studies that specifically analyzed the GHRM practices adopted in sustainable SMEs using a qualitative method [39]. Therefore, this paper provides a contribution to fill this gap by investigating these underexplored topics by adopting the case study methodology (that is useful for exploring poorly developed areas of research [40]) with a qualitative approach through semi-structured interviews with employees of Italian green SMEs. More specifically, this case study has been conducted in order to answer the research question, namely, to what extent Green Soft Skills and Green Leadership are relevant for green firm performance. Accordingly, this article aims to identify the drivers of working for a sustainable SME, to understand the key skills useful to work in a sustainable SME, and to detect the main GHRM practices adopted in a sustainable SME.

The current article is structured as follows: Section 2 will present the theoretical framework, which reports what emerges from the international literature on the topic of GHRM, Green Leadership, and the relationship between soft skills and CSR development and efficacy. Then, Section 3 will provide the methodology adopted for the empirical part, while Section 4 will report the results of the thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews conducted with workers of Alimentiamoci s.r.l., an innovative Italian startup founded on 22 November 2019, which offers sustainable products and services in the food sector. Section 5 will present the discussion of the results, and Section 6 will describe limitations and suggestions for future research. In conclusion, Section 7 will propose the findings and concrete applications of the results.

2. Theoretical Framework

Within the current global context, the increase in environmental issues has led to the assessment of new environmentally friendly disciplines inside organizations like Green Management, Green Marketing, Green Retailing, Green Accounting, etc. [17,41]. Hence, companies can contribute to facing environmental requirements through the implementation of strategies supported by Human Resource practices aimed at managing and guiding employees toward green awareness, behaviors, and objectives in order to reach a high level of sustainability and CSR [42,43].

2.1. Green Human Resource Management

In the extant literature, the contribution of Human Resources (HR) to Green Management objectives and strategies is known as Green Human Resource Management (GHRM). This discipline represents the compromise between traditional HR practices and environmental corporate objectives [44] and focuses on the importance of managing human behaviors to pursue a company’s environmental performance and goals [30].

Some of the most common practices of GHRM, also known as “factors” or “dimensions” [45,46], are the following [47]:

- -

- Recruiting and Selection: In this initial phase, companies try to attract and select new employees who are aligned with their vision and missions and can contribute to achieving their goals once they enter the company [48]. In particular, green firms have to select and hire employees who share and support the corporate interests in the environment in order to create a green and performing workplace [30];

- -

- Education, Training, and Development: The process of training is defined as a planned organizational action that helps employees acquire and develop hard and soft skills with the aim to implement their growth and their future performance, helping them to be innovative [49,50];

- -

- Performance Evaluation: During this phase, the company analyzes employees’ contributions, performance, behaviors, work results, and possibly additional compensation [51,52];

- -

- Rewards: This process of Green Pay and Rewards (GPR) regards all the financial and non-financial payments used to compensate employees (e.g., pay, praise, promotion, accomplishment, etc.) [5,53];

- -

- Benefits: This practice includes all the compensation that is not part of the defined salary that can be an incentive and can impact employees’ commitment and job satisfaction [49,54];

Based on the size and type of organizations, other practices can be developed in addition to those proposed, such as empowerment of employees, manager involvement, employee life cycle, etc. [55].

In order to succeed in implementing Green Management through GHRM, it is important that employees understand the sustainability-oriented practices, policies, and strategies proposed by the organization by growing their awareness through participation in environmental training initiatives. These can develop employees’ skills and produce enduring motivation, knowledge, and commitment, namely an increase in their willingness to contribute to their behaviors and performance toward corporate goals [34,56].

The recruitment and selection practices of HRM and GHRM are closely related to the expectations, values, and goals of both workers and the company and linked to the concept of the psychological contract, which can be defined as a set of unwritten, implicit, and reciprocal expectations between future candidates or employees and the organization that specifies the reciprocal exchange agreement and the obligations implied in the working relationship [57,58,59]. Hence, the psychological contract represents an alignment between the employee and the corporate vision and mission, and this can be extremely useful in order to create commitment and a strongly shared organizational culture, namely a pattern of shared basic assumptions that create a cohesive system of meaning and symbols in terms of which interactions, adaptation, and integration take place [60,61]. For a company, creating and sustaining a strong organizational culture shared by aware and committed employees can represent a great support and a competitive advantage in order to improve performance and achieve corporate goals [62].

Additionally, although the importance of training is widely recognized [33], the concrete relevance of environmental training is now increasingly emerging. The environmental training practice is considered one of the most important tools of GHRM in order to achieve corporate sustainability, providing employees with the essential knowledge and awareness to manifest Green Behaviors and deal with the present environmental problems and opportunities, developing their skills and increasing the meaningfulness of their work [24,42,63].

Regarding employees’ behaviors that are sustainability-oriented, two types can be defined: Task-Related Green Behaviors (TRGB) and Voluntary Green Behaviors (VGB) [64]. While TRGB include behaviors that fall within the work duties required of employees, VGB are spontaneous Green Behaviors that go beyond organizational expectations [65], and both types can be affected by leadership support and are useful to achieve corporate objectives [42].

What has been expressed so far allows us to understand how every individual’s behavior and skills constitute an essential resource for the organization to concretize business strategies, achieve business objectives, and improve business performance.

In order to manage all the factors involved, it is necessary to implement Green Leadership, which can manage sustainable strategies by guiding employees toward greater environmental awareness and the achievement of the company’s goals [11].

2.2. Green Leadership

The importance of human capital and HRM to reach high corporate performance has been extensively analyzed in the literature [66] and emphasizes the need to develop leadership strategies able to orient employees toward the development of their competencies and capabilities, the attainment of corporate objectives, and the creation of a competitive advantage [67].

In particular, the environmental scenario requires the integrated application of Green Management, GHRM, and Green Leadership approaches to guide individuals toward green innovation, generating superior green job behaviors, and green employee performance, as well as corporate ones [68,69,70].

In general, the role of a leader is to select, equip, train, and influence individuals with different abilities and skills, with the aim to inspire and direct their enthusiasm, emotions, and energy toward common objectives [71]. From an organizational point of view, the term leadership includes (i) giving a new direction to the organization; (ii) putting in place problem-solving ability, creativity, and innovative thinking; (iii) building corporate structures; and (iv) improving quality [72]. These aspects of leadership must be incorporated into the environmental business scenario to create Green Leadership, a concept that encompasses different facets, such as Sustainability Leadership, Globally Responsible Leadership, Eco-Sensitive Leadership, etc. [73]. Indeed, in the recent literature, it is possible to see how different traditionally recognized leadership styles have been applied to the green context. For example, Green Transformational Leadership (GTFL) is defined as a behavior that inspires and supports employees in their development by providing them with a clear vision of the environmental goals that the company wants to achieve and by motivating them to acquire new knowledge and be involved in the sustainable process of innovation [68]. This definition is based on the concept of Transformational Leadership [69,74,75].

Another type of leadership is Green Inclusive Leadership (GIL), which refers to an extremely open, available, and helpful leader who motivates and encourages employees by working closely with them in order to build trust and integrity and achieve environmental objectives [76,77,78].

Moreover, Green Servant Leadership (GSL) can be identified as a type of leadership that focuses on employees’ interests and needs and acts to provide a role model of empathy, altruistic love, and compassion [79,80,81] with the aim of empowering and pushing people to be green employees, improve their green performance, and attain green corporate goals [82,83].

Other strategic leadership styles for business sustainability have been identified: Stakeholder, Ethical, and Sustainable [73]. Stakeholder-based Leadership focuses on managing stakeholders’ relationships (e.g., with owners, board members, managers, employees, suppliers, consumers, competitors, etc.) and gaining reputational effectiveness from multiple constituencies [84,85]. Ethical Leadership identifies behaviors that are particularly influenced by a leader’s personal features (e.g., authenticity, integrity, self-discipline, intentions, etc.) and moral obligations (e.g., justice, duty, greater good, etc.) and interests that are more oriented to the maintenance of care and respect by aiming to retain ethical business standards [86,87]. Sustainable leadership promotes long-term business sustainability by trying to balance people, profits, and planet needs by applying Humanistic Management [88] and pledging to foster continuous change and systemic innovation [89]. Particularly, this Green Leadership style incorporates several characteristics that are usually attributed to other styles of leadership (not exclusively green-oriented), such as prioritizing corporate needs rather than personal ones (Servant Leadership); being attentive to social issues (Responsible Leadership); promoting ethical behaviors (Ethical Leadership); inspiring, motivating and intellectually stimulating employees (Transformational Leadership); sharing authority through employees’ participation and empowerment (Shared Leadership); and pursuing spiritual values (e.g., humility, integrity, honesty, etc.) with the aim of becoming trustable (Spiritual Leadership) [90].

2.3. Skills and Sustainability

Following the considerations in the previous sections, it is possible to understand how the current environmental scenario is continuously putting companies in challenging conditions, which can be partially solved by hiring individuals called “Green Employees”, namely individuals who care about environmental issues. Specifically, they are characterized by an intrinsic motivation to safeguard the environment through work and possess environmental values and beliefs [91]. Regarding skills, a distinction between two macro-categories is generally made by scholars: hard and soft. Hard skills are defined as those technical skills related to knowledge, education, and work experience (e.g., the ability to write, type, and read; the ability to manage equipment, data, software, etc.) that allow the performance of specific tasks; soft skills are defined as character traits, attitudes, and behaviors not directly linked to acquired knowledge. Soft skills can also be identified as personal transversal competencies (e.g., emotional intelligence, stress management, teamwork, creativity, etc.) and considered strategic to enhance individuals’ performance and career prospects [92,93]. In addition, soft skills can be further categorized as intrapersonal and interpersonal skills, which, respectively, represent the ability to manage oneself with personal cognitive skills (i.e., knowledge skills, thinking skills) and the ability to handle interactions with others using social skills (e.g., communication, listening, networking, problem solving, decision making, etc.) [94,95].

Focusing on sustainability, the extant literature provides the definition of “Green Skills”, which refers to all the knowledge, skills, competencies, and attributes required of workers employed in green jobs [96]. Under this umbrella term, a variety of specific skills (both hard and soft) is included, and they can be divided into three dimensions [31]: (a) cognitive, which refers to the knowledge concerning environmental protection; (b) psychomotor, which refers to the ability to, for instance, minimize energy consumption or to conserve water resources; and (c) affective aspect, which refers to the motivation of individuals to conserve natural resources and efficiently manage waste. Indeed, researchers demonstrated that skills related to, for instance, environmental awareness, leadership, and management skills, as well as efficient energy usage, water resource conservation, and zero waste management, are relevant to guiding the green transition of firms and SMEs [96,97]. Considering the present complex scenario and current challenges, companies require employees that can bring soft skills such as problem solving, critical thinking, and creativity, as well as decision making, compassion, empathy, cooperation, leadership, etc. [98,99,100]. Accordingly, senior managers interviewed by Strachan and colleagues [101] identified the need for more ‘soft’ transferrable skills rather than ‘hard’ technical skills to deliver the transition to a sustainable green economy. Besides soft skills, Chen and colleagues [102] identified the key role of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy in sustaining employees’ green performance. The concept of green mindfulness can be defined as “a state of conscious awareness in which individuals are implicitly aware of the context and content of environmental information and knowledge” [103]. By sustaining the ability to focus on the present [104], mindfulness enhances employees’ abilities to detect information useful to solve potential problems and leads them to adopt adaptive coping strategies that act directly on the source of the problem. Differently, green self-efficacy is defined as “the belief in individuals’ capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to achieve environmental goals” [103]. Indeed, self-efficacy refers to people’s beliefs of being able to gain specific levels of performance and to reach specific purposes [105]. Employees with higher levels of self-efficacy will be more likely to engage in behavior and activate sufficient effort to obtain outstanding outcomes. Furthermore, green mindfulness and green self-efficacy have been found to be positively related to green creativity [103], defined as the ability to develop new ideas about products, services, processes, or practices useful to reach environmental goals [69]. Green creativity is crucial for the green product development performance of companies and allows them to efficiently respond to green requirements, achieving a competitive advantage [106].

In the extant literature, there are several studies, such as those mentioned above, that point out the importance of green skills for green firms and their performance. Through an analysis of the literature on the topic, it emerged that no specific classification is available concerning the relevance of the different green skills, whether soft or hard, as it depends on internal, external, and contextual factors that characterize each organization operating in the green field.

For example, Sern and colleagues [31] identified the ten most common green skills demanded by various industrial sectors investigated in their research (e.g., leadership skills, management skills, energy skills, city planning skills, landscaping skills, communication skills, waste management skills, etc.), while other authors such as Cabral and Dhar [35] highlighted the importance of other green skills (e.g., recycling skills, environmental protection skills, energy conservation skills, green awareness skills, etc.). Additionally, Farooq and colleagues [107] defined other green skills as more relevant to support ecological behaviors in the workplace (e.g., environmental consciousness, green mindfulness, and green awareness).

Moreover, although scholars recognized the need to have a skilled workforce to support the transition to a green and sustainable economy, little is known about what skills are required in the Italian context and in the different industry sectors. Investigating this topic is relevant because it represents the basis upon which education and skill-formation systems should be planned and organized [96]. By analyzing the case study of an Italian sustainable SME operating in the food sector, this study contributes to shedding light on these aspects.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Method

In order to explore the research questions, the current research adopts a qualitative research methodology following an inductive approach (https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/BFJ-04-2020-0306/full/htmlbased, accessed on 26 September 2023) on a case study. The qualitative design allows for the investigation of the topic of interest in a deeper and more detailed way than allowed by the quantitative approach [108] by offering the possibility of understanding the personal opinions and meanings shared by the participants during semi-structured interviews. Additionally, a case study has been adopted as it represents an appropriate methodology to investigate contemporary phenomena in real-life situations [109], and it has been demonstrated to be an effective research method in the context of organizational behaviors [110]. Indeed, several authors adopted a qualitative methodology based on case studies to explore topics related to SMEs [111,112]. However, little is known about Italian SMEs that offer sustainable services and products in the food sector. Finally, we used both primary and secondary research data. The source of primary data is represented by semi-structured interviews, while secondary data are derived from the company website and sustainability reports, which were both used to provide the description of the company included in the following section.

3.2. Description of the Company

The research analyzes Alimentiamoci s.r.l., an innovative SME located in Northern Italy, as a case study. This company, which has a total of 57 workers, develops, produces, and markets innovative products and services with high technological value that benefit the environment, health, and the local economy, with a focus on the food sector according to its vision “Make the world a little bit better than how we found it”. Specifically, in line with goal 12 of the United Nations Agenda 2030 [113], the main purpose is limiting food waste through the creation of Planeat, a food expenditure planning platform that enables food waste reduction, in order to realize a sustainable, innovative ecosystem that maximizes the common good. Saving food and water results in the reduction of CO2 and H2O used in the production of both food and the materials used for compostable packaging, thereby addressing goal 13 of the United Nations Agenda 2030 [113]. Table 1 and Table 2 report some objective data provided by the company.

Table 1.

Objective data provided by the company about food saved and the related savings of CO2 and H2O.

Table 2.

Objective data provided by the company about plastic saved and the related saving of CO2.

How does the company achieve these goals?

Planeat targets both families and businesses by providing a platform through which customers can:

- Plan the menu and weekly food shopping (for families);

- Purchase ready-to-cook meal kits (for families and businesses);

- Order pre-made meals (for families and businesses).

The focus on the food sector is derived from the fact that food production is responsible for 26% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and 24% of these emissions depend on food that is thrown away and not consumed [114]. Furthermore, Planeat wants to achieve sustainable goals not only in terms of environmental impact but also in terms of social impact. Indeed, consistent with goal 8 of the United Nations Agenda 2030 [113], it also supports sustainable employability, including part of the population that might remain marginalized. To do this, the company forges partnerships with nonprofit organizations from which they recruit candidates with the greatest need to find jobs (e.g., asylum seekers, immigrants, unaccompanied minors, unemployed people in distress, current or former detainees). Similarly, in order to promote the re-education and social reintegration of people, according to Article 21 (L. 354/75), in 2022, the company welcomed a detainee to its workforce. Besides this goal, Planeat also strives to foster gender equality.

Finally, they also adopted holacracy, an innovative and sustainable organizational management method based on decentralized management that implies a shift from a conservative management chain of command to an innovative allocation of authority that horizontally distributes power, authority, and decision making through self-managing teams [115,116,117]. The teams can be named “circles” or “holons” and identify an environment in which every individual can cover multiple roles and leadership functions and manifests high levels of adaptability, constant contact, tolerance, systematical approach, and involvement in all aspects of corporate business [118,119].

This practice promotes a more effective and egalitarian organization of work, where processes are fluid, rules are transparent and clear, and in which everyone is involved in the pursuit of a common purpose by being responsible for themselves with the support of their colleagues. Sharing of progress and results takes place weekly through a meeting called “tactical”, which involves the exchange of views between the various job roles. This allows the entire organization to stay updated on the progress of open projects by effectively participating in the life of the company and empowering everyone to raise possible concerns to be settled and resolved, as long as they are geared to the company vision: generate value for the system surrounding the company and consequently for the company itself.

3.3. Data Collection

Primary data were collected through semi-structured interviews. A preliminary meeting between the research team and the CEO of the company has been made in order to explain the main purpose of the research and the methodology used, in addition to asking him for permission to use the name of the company and to involve some employees in semi-structured interviews. In addition, the criteria for participation in the study have also been defined: participants must be (1) native Italian speakers, (2) at least 18 years of age, and (3) employed by the company for at least 1 year. After having obtained the permission of the CEO, according to the criteria defined, the HR managers of the company provided the research team with a list of e-mail contacts of the 57 employees who were then contacted by e-mail. The research team arranged the interviews to cover all the departments of the company, with at least one participant for each. Before starting the interviews, participants filled out an informed consent form, which included details about participation procedure, study contents, data collection purposes, future data dissemination modalities, participants’ rights, and reference contacts. Additionally, they were invited to provide some socio-demographical data (i.e., gender, age, work experience, job tenure, education level, job role). Furthermore, in order to put them at ease, they were informed that they were expected to answer honestly, based on their experiences, and that there were no right or wrong answers. Participation was voluntary, and participants were free to withdraw at any time.

The main objective of qualitative research is to obtain a deep understanding of a specific area of interest. Therefore, the validity of a qualitative study is more related to the richness and depth of the answers provided by participants rather than to the sample size itself [120]. Accordingly, the concept of saturation (i.e., the point at which no new themes emerged from data and the new information analyzed creates little or no changes in code definitions [121]) represents the guiding principle for qualitative inquiries [122]. The current research obtains a sufficient sample size with data saturation achieved after thirteen interviews. This is consistent with previous research suggesting that data saturation is usually achieved with a number from 6 to 16 interviews [123] and, more specifically, with approximately twelve interviews [121,124].

A total of 13 workers participated in semi-structured interviews conducted during June and July 2023 by three researchers. Characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of the sample (N = 13).

Having obtained consent from participants, all interviews were audio-recorded. The interviews—lasting between 40 and 60 min approximately—took up different thematic areas reflecting the interests of scholars and practitioners. Given the semi-structured nature of the interviews, open-ended questions were elaborated in order to leave space for participants to express their personal observations and experiences. Based on the analysis of the extant literature, the semi-structured interview protocol was prepared by including questions used in previous studies [34,100,125,126]. As already conducted by previous studies [127], the interview protocol was subjected to a preliminary test by asking the opinion of three employees to identify potential ambiguities in the questions. The questions were then reformulated to incorporate their suggestions and, according to other studies [128,129], the interview protocol was authenticated by a panel of four experts (two academics and two experts of qualitative research) that analyzed the questions and made some amendments that were incorporated in the final version of the interview protocol including 50 questions. Examples of some questions (12 out of 50) used during the interviews are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Example of questions of the semi-structured interviews.

3.4. Data Analysis

Recorded data were transcribed verbatim by removing all personal information. NVivo 12.0 software was used to facilitate the thematic analysis, as done by previous researchers who carried out qualitative studies in the field of organizational behavior (e.g., [39,130]. Following the methodology proposed by Braun and Clarke [131], the authors read through the transcriptions of the interviews several times to familiarize themselves with the content. Initial codes for data were identified and then analyzed to understand how they can be combined into potential themes. A thematic map was created to reflect on the codes and themes identified. At this point, each theme was reviewed to check if it was coherent with the coded data extracted and in relation to the whole dataset. Once this was achieved, names were given to the themes, and meaningful extracts that best represented each code and theme were chosen.

4. Results

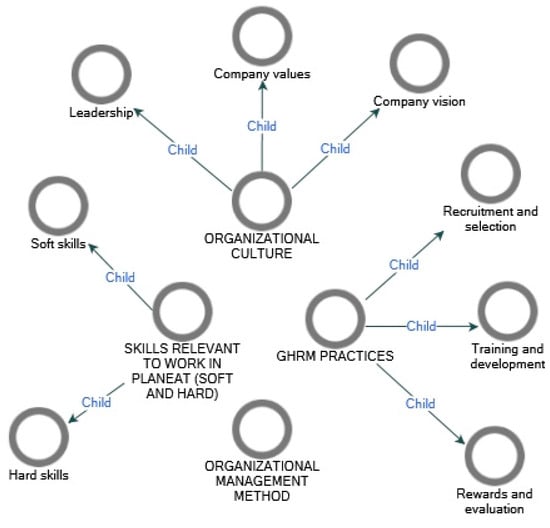

The results will be described in the following four sections, corresponding to the four main themes that emerged through the thematic analysis of interviews: organizational culture, skills relevant to work at Planeat (soft and hard), GHRM practices, and company organizational management method (see Figure 1). Categories and codes for each theme will also be reported.

Figure 1.

Summary of thematic analysis results.

4.1. Organizational Culture

Three dimensions of the organizational culture underlying participants’ choice to work at Planeat were identified. First, participants identified the leadership of the CEO as the main reason that explains their willingness to work at the company. They described the leader as a person capable of inspiring others, recognizing the autonomy of each employee in decision making, and conveying company values. Additionally, the leader demonstrated the ability to listen to people’s opinions, involve them, and build consensus. The second dimension of organizational culture refers to company values (defined and shared by the leader, the CEO and founder of the company), which are the crucial building blocks that link culture, vision, mission, leadership, psychological contract, engagement, and performance. Consistent with the leader’s behaviors and with the previous literature on caring HRM practices [132], the core value refers to caring for people, followed by caring for the environment and social inclusion. Finally, the company vision is reported as the third main reason for working at Planeat, as it represents the desire to make the world a better place (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Organizational culture.

4.2. Relevant Skills to Work at Planeat (Soft and Hard)

When participants were asked about the key skills needed to work at Planeat, several soft skills emerged. According to previous studies [94,101,133], we categorized them into three groups: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and green skills. Among the intrapersonal skills, the ability to set and manage priorities was recognized as one of the most relevant skills, probably because of the autonomy that the CEO gives to each employee. Moreover, as the company is trying to sell a new type of service that requires a change in customer habits, participants said they need to be flexible and able to adapt when a specific path taken (e.g., a marketing strategy) does not lead to the desired results. Among the interpersonal skills, three main skills emerged. Firstly, almost all participants indicated the ability to work in a team as a core competency, intended as the ability to collaborate, to recognize the needs of colleagues, and to help each other. Also, almost all respondents recognized the ability to promote change outside the company as necessary because their core service (i.e., selling groceries online) requires a change in people’s habits. In addition, the third key interpersonal skill is related to the ability to communicate and to adapt the communication styles to suit people’s personalities. Finally, participants also mentioned the need for green skills, which was related to the sensitivity to the environment and the awareness that if we all take little actions to protect the environment, we will be able to achieve relevant results. Regarding this point, almost all participants believe that their sensitivity to the environment has increased since they started working at Planeat. Additionally, they also recognized creativity as one of the key skills needed because of the novelty of their service, which requires them to continuously find new strategies and innovate by identifying new products to improve their environmental standards (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Soft skills.

Participants acknowledged little importance regarding technical skills because they are convinced that these skills can be learned easily if an employee meets the values and the soft skills needed. Some of them are mentioned as hard skills: the knowledge of legislation skills in software programming and accounting (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Hard skills.

4.3. Green Human Resource Management Practices

The principal GHRM practices adopted in the company and mentioned by participants can be grouped into three different categories: Recruitment and Selection, Training and Development, and Rewards. Consistent with the findings reported in the previous sections, most participants reported that personal values represent the most relevant aspect considered during the selection phase, to the point that they do not hire people who do not share the company values even if they have excellent technical skills. Moreover, some participants said that soft skills (e.g., the ability to work in a team and collaborate to foster change outside the organization) were more relevant than hard skills. As regards training and development, the majority of participants attended volunteer activities suggested by the company (e.g., garbage collection along the river and delivering free meals to the homeless), reporting that these were informal learning opportunities that fostered their awareness of environmental and social issues. It is relevant to consider that these activities were organized during their free time (i.e., weekends), showing that employees of Planeat take care of the environment and adopt sustainable behaviors not only during working hours or when they are physically in the workplace—with the aim to follow organizational rules (i.e., Task-Related Green Behaviors)—but also during their leisure time (i.e., Voluntary Green Behaviors). Half of the interviewees also took part in formal training courses provided, for instance, by universities and technology training courses organized within the company. Importantly, the company encourages employees to seek out and participate in training activities. Finally, regarding rewards and evaluation, participants said that their sustainable behaviors are usually followed by appreciation from other colleagues, but the company does not provide financial rewards (see Table 8).

Table 8.

HRM practices.

4.4. Organizational Management Method

This company uses holacracy as an organizational management method. During interviews, employees described how this practice is applied in their company, explaining that each employee is responsible for his/her role and actions. Each staff member works as a team with other staff members who have a role in the same area. Therefore, the system is composed of several teams collaborating to reach shared goals. Once a week, there is a meeting (called “tactical”) used to share the status of one’s work with others. During these meetings, it is possible to ask for help from more experienced colleagues to solve specific issues or ask the opinion of the CEO when an important decision needs to be made (Table 9). The adoption of this method allows for an understanding of why participants recognize the particular importance of the ability to work in a team and communicate with others.

Table 9.

Organizational management method.

5. Discussion

Today, global warming and environmental issues are increasing workplace complexity and competitiveness [134]. In other words, the impellent need to reduce the impact of societies on the environment is putting new and additional challenges on organizations, their leaders, and employees. For instance, the pressure to deliver sustainable services and products is growing, and customers are paying more attention to these aspects, especially in the food sector [135]. Companies cannot fail to take into account the new needs of consumers and the need to adapt their production standards to the logic of greater sustainability. To deal with this need, companies must rely on workers with specific skills and behaviors [90]. Since people represent a critical asset for organizational success [136], there is a growing need to hire workers able to operate in a context characterized by uncertainty and changes in job roles and activities [137]. The extant literature highlights that more research is needed to better understand which factors are relevant for sustainable SMEs. Accordingly, this article performed a qualitative study with a threefold purpose: to identify the main drivers of working for a sustainable SME, to understand the key skills relevant to working in a sustainable SME, and to detect the main HRM practices adopted in a sustainable SME.

In response to the question regarding the main reasons behind the choice to work at Planeat, participants indicated some aspects related to the organizational culture. Firstly, they indicated their willingness to work with the CEO of the company because of his strong ability to inspire others, recognize autonomy in decision-making, convey values, and listen to and engage people by building consensus within the company. The second reason mentioned is related to sharing the company values regarding caring for people and the environment, as well as social inclusion.

It is clear that the values underlying organizational culture are defined by the leader or the governance of the organization.

Accordingly, our findings revealed the importance of leadership for the employees interviewed and, at the same time, the crucial importance of culture and values.

Considering these aspects, employees chose to work at Planeat because they share the vision of the company to “make the world a better place” and are driven by the concern for their children and for future generations. Consequently, it seems that this company is characterized by sustainable leadership (which is based on the assumptions of Responsible Leadership, Transformational Leadership, Servant Leadership, Spiritual Leadership, Ethical Leadership, and Shared leadership [90]), which recognizes the significance of people, through the application of Humanistic Management, and promotes long-term sustainability as well as systemic innovation. Indeed, the previous literature suggested that sustainable leaders share the company vision with collaborators, support their development, and are committed to building an ethical workplace characterized by trust, participation, empowerment, teamwork, and knowledge sharing [89]. They value every person as a whole and are careful in considering the environment without losing sight of economic issues [90]. Both aspects reflect the three main values mentioned by participants (i.e., care for people, care for the environment, and social inclusion) and, thus, demonstrate that the CEO particularly cares for each person, society, and the environment. The particular attention dedicated to each collaborator emphasizes the fact that they are considered more than just workers; this creates a sense of community that fosters employees’ enthusiasm and engagement [12] and goes beyond Planeat as a mere workplace. Taken together, these aspects suggest that they adopt Humanistic Management [138], even if the leader and the employees are not aware of it. By identifying how this leadership style can be adopted in a sustainable SME, this study contributes to the current limited literature on sustainable leadership [139].

According to the Food 2030 Strategy of the European Commission, skills play a key role in helping companies overcome the main challenges regarding the increasing competition for natural resources, climate change, and resource scarcity [140] by highlighting the need to detect the most relevant skills necessary to work in sustainable SMEs. In this regard, it is relevant to note that, when asked to indicate the main skills necessary to work at Planeat, almost all participants reported different soft skills, while only three employees indicated some hard skills (i.e., the need to know the rules, to possess skills in software programming, and to pay attention to the company expenses). This finding is coherent with the results that emerged in previous studies [100,101] and indicates that soft skills seem to be more relevant than hard skills. This is linked to the leader, the values, and the organizational culture. In this regard, our findings showed that people working at Planeat must be able to set and handle priorities and be flexible. This is coherent with the leadership style adopted, which recognizes responsibility and autonomy to each collaborator, as well as with the adoption of holacracy [141]. Moving on to interpersonal skills, according to the results of Sujová and colleagues [98], the ability to work in a team is the most mentioned by participants. Most likely, this ability is fostered by the adoption of holacracy, a method of organizational management based on the work of self-managing teams [115]. However, it is relevant to note that, when speaking about the ability to work in teams, participants refer both to the ability to collaborate in order to reach a common goal and to be aware of the state of wellbeing of others in order to provide help and support when needed. Working as a team in this way sustains the creation of a healthy work environment in which, according to Humanistic Management [88], a central value is recognized by people [36].

Finally, participants reported green skills as key to working for a sustainable company. Among this group, they mentioned the ability to be sensitive to the environment and to be aware that sustainable and respectful actions are useful to protect the environment, suggesting that participants possess a certain level of green self-efficacy. This is particularly relevant as previous studies demonstrated that people who believe that their actions can have a positive impact on the environment are more likely to adopt these kinds of actions [105]. Moreover, almost all participants reported having always been environmentally conscious (e.g., values handed down by the family), but they also said that this had been further developed and stimulated when they started working at Planeat. Furthermore, green creativity is reported by different participants as a key ability because of the novelty of the services that Planeat is selling. Indeed, participants said that they encounter difficulties in selling their services as it requires a change in the consumers’ habits. Therefore, they often need to creatively rethink the strategy used to find new consumers and to spread the services by requiring them to implement lateral thinking and problem-solving skills. This finding is in accordance with the previous literature recognizing a key role in creative thinking [98,99] and, specifically, in green creativity in the food sector [142]. Therefore, by identifying soft skills as more relevant than hard skills, this research contributes to the literature about soft skills in the green sector and Italian SMEs. Additionally, this study adds to the scientific literature on holacracy, which is still in its infancy [143], by showing how some soft skills are relevant to working in a company that adopts this organizational management method and how this can foster the sustainable development of organizations.

Accordingly, when talking with participants about GHRM practices, they reported that personal values and soft skills represent the key aspects on which the outcome of the selection process depends. This reflects the main values on which the organizational culture is based. Focusing the recruitment and selection process on personal values and soft skills, HR managers of Planeat are able to evaluate the person–organization fit [42] and, hence, the psychological contract that has been demonstrated to be positively related to job performance [144]. This leads to the creation of a strong psychological contract and sense of belonging among employees. Therefore, green recruitment and selection help the company to have a workforce aligned with an organizational culture that shares green ideologies and sustains the reaching of sustainable goals. Additionally, regarding green training and development, participants reported that the company encourages HR to participate in training activities. Most of the participants—including the CEO—participated in activities that can be considered informal training. For instance, these activities included collecting plastics along the river or delivering free meals to the homeless. According to Gim and colleagues [145], participants reported that these kinds of activities were useful in boosting sensitivity and awareness of the environment, including social issues, and being more conscious about the effects of their actions on the environment [42]. Green training has been found to be the GHRM practice more able to foster Italian employees’ pro-environmental behaviors [146]. Moreover, in addition to the commitment of its employees to participating in the social-related activities just mentioned, it emerged that in the recruiting and selection phase, the company showed concern for underprivileged groups of people by hiring, for instance, a Human Resources person from the prison in order to support its social reintegration as planned by Italian law. Along with the importance of recognizing human values and hearing employees’ needs and opinions through the holacracy system, this showed how the company pays attention to the social aspects of sustainability both outside (by encouraging employees to participate in social activities) and inside (by recognizing values to each Human Resource) the company. This has shown that Planeat seeks to operate in a sustainable way not only from an environmental but also from a social point of view.

Although previous studies demonstrated that green rewards and compensation are relevant to engaging employees in environmental activities and eco-friendly behaviors [39], the analysis of the interviews allowed us to detect that no financial rewards are given by the company. Participants said that they are all voluntarily committed to adopting sustainable behavior because they share the company values; therefore, it is not necessary to receive incentives from the company. However, they also recognize that eco-friendly behaviors are often followed by appreciation from other colleagues reporting that some kind of non-financial and intangible rewards exist in the company. Although GHRM practices are receiving growing interest from scholars, to date, little is known about this topic among Italian employees. Therefore, this study provides a contribution to the management literature by exploring what kind of GHRM practices are adopted in a sustainable Italian SME in the food sector.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this research offers several contributions to the literature, it is important to underline some limitations. Our findings derived from semi-structured interviews conducted with a small sample of people employed in a sustainable Italian SME operating in the food industry, thus limiting its generalizability. Additionally, in this specific case study, the data collected demonstrated an alignment of the points of view of the interviewees. Future studies should be developed in larger companies to detect potential differences in opinions between workers employed in different departments (for instance, HR specialists may have opinions different from those of workers employed in other departments). Moreover, the research takes into account the awareness of the risk of respondents’ response bias. Therefore, it would be useful to conduct similar studies in other countries or adopt a cross-cultural perspective in order to verify the generalization of our findings. Moreover, as this study is useful to explore some key themes (e.g., skills, HRM practices) in sustainable SMEs, to ensure the integrity of the findings, we suggest implementing a mixed-method design (by integrating qualitative with quantitative data [147]) and triangulate the different source of information (e.g., interviews, observation and field notes [148], that was not possible to implement in the current study due to timing constraints and agreements defined by the company Additionally, as Planeat is a recent project, it would be useful to re-collect the data in the coming years to verify if the themes are still the same. Finally, although in this study, the attention has been mainly dedicated to the environmental part of sustainability and secondly to the social level, it would be useful to delve into social and sustainable HRM and explore the financial aspects [149,150].

7. Conclusions

In these turbulent times, in which being environmentally sustainable is a concern of an increasing number of people and companies, reducing food waste represents one of the major challenges of circular economies. Therefore, it became relevant to analyze and discover how companies can contribute to these challenges. Accordingly, by analyzing the content of semi-structured interviews carried out with employees of an innovative Italian SME, some key themes related to the organizational culture, skills relevant to work at Planeat (soft and hard), GHRM practices, and the organizational management method were identified. It emerged that this company adopted holacracy and recognized a central value to humans along with the environment. The sustainable leadership characterizing this company recognizes the great importance of the soft skills of collaborators, and green recruitment and selection are used to attract people who share the same values in addition to fostering their willingness to take part in green training. Based on such findings, it seems crucial that sustainable SMEs adopt GHRM practices that can support the attraction of people who share the company values in order to create a cohesive workforce and establish a strong psychological contract. The findings of this research suggest that HR managers should be trained on how to match their collaborators’ and organization’s values [90] as well as on how to implement eco-friendly recruitment processes [151]. In addition, it is relevant that these companies have sustainable leaders able to effectively share the company’s sustainability-related vision and, at the same time, able to support their collaborators [90]. To conclude, given the key role that soft skills play in this research, it is necessary that universities incorporate specific training in different degree programs. Companies should also promote the participation of employees in specific programs aimed at improving soft skills.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F., C.B. and C.R.; methodology, C.F., C.B. and C.R.; software, C.B.; validation, C.F., C.B. and C.R.; formal analysis, C.B.; investigation, C.F., C.B. and C.R.; resources, C.F., C.B. and C.R.; data curation, C.F. and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.F., C.B. and C.R.; writing—review and editing, C.F., C.B. and C.R.; visualization, C.R.; supervision, C.F.; project administration, C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the interview privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- González-Benito, J.; González-Benito, Ó. Environmental Proactivity and Business Performance: An Empirical Analysis. Omega 2005, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Global Warming: Should Companies Adopt a Proactive Strategy? Long Range Plan. 2006, 39, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodland, R. The Concept of Environmental Sustainability. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1995, 26, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.; Hill, M.; Gollan, P. The Sustainability Debate. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1492–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. Green Human Resource Management: Policies and Practices. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2015, 2, 1030817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo Alamillos, R.; de Mariz, F. How Can European Regulation on ESG Impact Business Globally? J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletič, M.; Maletič, D.; Dahlgaard, J.J.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.M.; Gomišček, B. Sustainability Exploration and Sustainability Exploitation: From a Literature Review towards a Conceptual Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Marrewijk, M. Multiple Levels of Corporate Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, J.; Karapetrovic, S. Systems Thinking for the Integration of Management Systems. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2004, 10, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElAlfy, A.; Palaschuk, N.; El-Bassiouny, D.; Wilson, J.; Weber, O. Scoping the Evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Research in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Era. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Buhovac, A.R. Solving the Sustainability Implementation Challenge. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.R. Green Management: The next Competitive Weapon. Futures 1992, 24, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloni, M.J.; Brown, M.E. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Supply Chain: An Application in the Food Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 68, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food Waste within Food Supply Chains: Quantification and Potential for Change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, C.; Dhir, A.; Akram, M.U.; Salo, J. Food Loss and Waste in Food Supply Chains. A Systematic Literature Review and Framework Development Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, C.; Stoessel, F.; Baier, U.; Hellweg, S. Quantifying Food Losses and the Potential for Reduction in Switzerland. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 764–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Environmental Performance: An Employee-Level Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane Haden, S.S.; Oyler, J.D.; Humphreys, J.H. Historical, Practical, and Theoretical Perspectives on Green Management. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.A.; Rondinelli, D.A. Proactive Corporate Environmental Management: A New Industrial Revolution. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1998, 12, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Claver-Cortés, E.; López-Gamero, M.D.; Tarí, J.J. Green Management and Financial Performance: A Literature Review. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1080–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Green and Competitive: Ending the Stalemate. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.-L.; Lin, S.-P.; Chan, Y.; Sheu, C. Mediated Effect of Environmental Management on Manufacturing Competitiveness: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 123, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Darnton, G. Green Companies or Green Con-Panies: Are Companies Really Green, or Are They Pretending to Be? Bus. Soc. Rev. 2005, 110, 117–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.A.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; de Jabbour, A.B.L.S. Relationship between Green Management and Environmental Training in Companies Located in Brazil: A Theoretical Framework and Case Studies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A.; Nagano, M.S. Contributions of HRM throughout the Stages of Environmental Management: Methodological Triangulation Applied to Companies in Brazil. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1049–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.B.; Auster, E.R. Proactive Environmental Management: Avoiding the Toxic Trap. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1990, 31, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Venselaar, J. Environmental Training: Industrial Needs. J. Clean. Prod. 1995, 3, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.J. (Ed.) The Industrial Green Game; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-309-05294-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. The Evolution of Environmental Management within Organizations: Toward a Common Taxonomy. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2006, 16, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sern, L.C.; Zaime, A.F.; Foong, L.M. Green Skills for Green Industry: A Review of Literature. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1019, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusiani, M.; Abidin, Z.; Fitrianingsih, D.; Yusnita, E.; Adiwinata, D.; Rachmaniah, D.; Anis Fauzi, M.; Purwanto, A. Effect of Servant, Digital and Green Leadership toward Business Performance: Evidence from Indonesian Manufacturing. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 1351–1361. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, M.E.; Mayer, D.W. Environmental Training: It’s Good Business. Bus. Horiz. 1992, 35, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perron, G.M.; Côté, R.P.; Duffy, J.F. Improving Environmental Awareness Training in Business. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, C.; Lochan Dhar, R. Green Competencies: Construct Development and Measurement Validation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Wiek, A.; Brody, M. Beyond Interpersonal Competence: Teaching and Learning Professional Skills in Sustainability. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntat, Y.; Othman, M.F. Penerapan Kemahiran Insaniah “hijau” (Green Soft Skills) Dalam Pendidikan Teknik Dan Vokasional Di Sekolah Menengah Teknik, Malaysia. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 5, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Buntat, Y.; Othman, M.; Saud, M.S.; Mustaffa, M.S.; Mansor, S.M.S.S. Integration of Green Soft Skills in Malaysian Technical Education. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2013, 19, 3718–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.U.; Wei, H.; Yue, G.; Nazir, N.; Zainol, N.R. Exploring Themes of Sustainable Practices in Manufacturing Industry: Using Thematic Networks Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B.; Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, R. Green Human Resource Management in Indian Automobile Industry. J. Glob. Responsib. 2019, 10, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Soomro, B.A. Effects of Green Human Resource Management Practices on Green Innovation and Behavior. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, A.; Koburtay, T.; Bourini, I.; Badar, K.; Gerged, A.M. Towards Sustainable Development in the Hospitality Sector: Does Green Human Resource Management Stimulate Green Creativity? A Moderated Mediation Model. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 32, 3217–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock-Millar, J.; Sanyal, C.; Müller-Camen, M. Green Human Resource Management: A Comparative Qualitative Case Study of a United States Multinational Corporation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 192–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B.F.; Huang, S. Achieving Sustainability through Attention to Human Resource Factors in Environmental Management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L. When Case Studies Are Not Enough: The Influence of Corporate Culture and Employee Attitudes on the Success of Cleaner Production Initiatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2000, 8, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H. Assessing Organizations Performance on the Basis of GHRM Practices Using BWM and Fuzzy TOPSIS. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 226, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S. Recruitment and Selection. In Managing Human Resources: Personnel Management in Transition; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 115–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; De Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Govindan, K.; Teixeira, A.A.; De Souza Freitas, W.R. Environmental Management and Operational Performance in Automotive Companies in Brazil: The Role of Human Resource Management and Lean Manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Seo, J. The Greening of Strategic HRM Scholarship. Organ. Manag. J. 2010, 7, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Rasad, S.B.M. Employee Performance Evaluation by the AHP: A Case Study. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2006, 11, 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A.; Nagano, M.S. Environmental Management System and Human Resource Practices: Is There a Link between Them in Four Brazilian Companies? J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1922–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, R.A. Types of Rewards, Cognitions, And Work Motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, C.; Ravichandran, S.; Karpinski, A.C.; Singh, S. The Effects of Training Satisfaction, Employee Benefits, and Incentives on Part-Time Employees’ Commitment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. How Green Human Resource Management Can Promote Green Employee Behavior in China: A Technology Acceptance Model Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.J.; Clark, K.D. Strategic Human Resource Practices, Top Management Team Social Networks, and Firm Performance: The Role of Human Resource Practices in Creating Organizational Competitive Advantage. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Career Dynamics: Matching Individual and Organizational Needs; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, J.P. The Psychological Contract: Managing the Joining-up Process. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1973, 15, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M. Psychological and Implied Contracts in Organizations. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1989, 2, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M. Understanding Organizational Culture; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, F.; Luqman, R.A.; Khan, A.R.; Shabbir, L. Impact of Organizational Culture on Organizational Performance: An Overview. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2012, 3, 975–985. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, B.F.; Bishop, J.W.; Steiner, R. The Mediating Role Of EMS Teamwork As It Pertains To HR Factors And Perceived Environmental Performance. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2011, 23, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Measuring, Understanding, and Influencing Employee Green Behaviors. In Green Organizations: Driving Change with I-O Psychology; Applied psychology series; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 115–148. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee Green Behavior. Organ. Env. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, H.; Segers, J.; van Dierendonck, D.; den Hartog, D. Managing People in Organizations: Integrating the Study of HRM and Leadership. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green Innovation and Environmental Performance: The Role of Green Transformational Leadership and Green Human Resource Management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H. The Determinants of Green Product Development Performance: Green Dynamic Capabilities, Green Transformational Leadership, and Green Creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, D.; Lyu, C.; Zhang, H. Does Seeing “Mind Acts Upon Mind” Affect Green Psychological Climate and Green Product Development Performance? The Role of Matching between Green Transformational Leadership and Individual Green Values. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, B.E.; Patterson, K. An Integrative Definition of Leadership. Int. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2006, 1, 6–66. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.R. Learning to Lead: A Handbook for Postsecondary Administrators; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Krittayaruangroj, K.; Iamsawan, N. Sustainable Leadership Practices and Competencies of SMEs for Sustainability and Resilience: A Community-Based Social Enterprise Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.B.; Lei, H. Determinants of Innovation Capability: The Roles of Transformational Leadership, Knowledge Sharing and Perceived Organizational Support. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Dhar, R.L. Effect of Green Transformational Leadership on Green Creativity: A Study of Tourist Hotels. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Ziv, E. Inclusive Leadership and Employee Involvement in Creative Tasks in the Workplace: The Mediating Role of Psychological Safety. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 22, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, T.A.; Farooq, R.; Talwar, S.; Awan, U.; Dhir, A. Green Inclusive Leadership and Green Creativity in the Tourism and Hospitality Sector: Serial Mediation of Green Psychological Climate and Work Engagement. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1716–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Crawford, J.; Türkmenoğlu, M.A.; Farao, C. Green Inclusive Leadership and Employee Green Behaviors in the Hotel Industry: Does Perceived Green Organizational Support Matter? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R. The Servant as Leader. In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Liao, C.; Meuser, J.D. Servant Leadership and Serving Culture: Influence on Individual and Unit Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dierendonck, D. Servant Leadership: A Review and Synthesis. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1228–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Effects of Environmentally-Specific Servant Leadership on Green Performance via Green Climate and Green Crafting. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2021, 38, 925–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.T. Integrating Green Strategy and Green Human Resource Practices to Trigger Individual and Organizational Green Performance: The Role of Environmentally-Specific Servant Leadership. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1193–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M. A Stakeholder Model of Organizational Leadership. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, T. Socially Responsible Leadership. Foresight 2003, 5, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciulla, J.B. Ethics and Leadership Effectiveness. In Discovering Leadership; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 2009; pp. 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Resick, C.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Dickson, M.W.; Mitchelson, J.K. A Cross-Cultural Examination of the Endorsement of Ethical Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 63, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melé, D. The Challenge of Humanistic Management. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable Leadership Practices for Enhancing Business Resilience and Performance. Strategy Leadersh. 2011, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Piwowar-Sulej, K. Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment Decoded: Sustainable Leaders, Green Organizational Climate and Person-Organization Fit. Balt. J. Manag. 2023, 18, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocirlan, C.E. Environmental Workplace Behaviors: Definition Matters. Organ. Env. 2017, 30, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, M.M. Executive Perceptions of the Top 10 Soft Skills Needed in Today’s Workplace. Bus. Commun. Q. 2012, 75, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laker, D.R.; Powell, J.L. The Differences between Hard and Soft Skills and Their Relative Impact on Training Transfer. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q 2011, 22, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimatti, B. Definition, Development, Assessment of Soft Skills and Their Role for the Quality of Organizations and Enterprises. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2016, 10, 97–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ciappei, C.; Cinque, M. Soft Skills per il Governo dell’Agire. La Saggezza e le Competenze Prassico-Pragmatiche; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Napathorn, C. The Development of Green Skills across Firms in the Institutional Context of Thailand. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2022, 14, 539–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyati, T.K.; Mutsau, M. Leveraging Green Skills in Response to the COVID-19 Crisis: A Case Study of Small and Medium Enterprises in Harare, Zimbabwe. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 13, 673–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujová, E.; Čierna, H.; Simanová, Ľ.; Gejdoš, P.; Štefková, J. Soft Skills Integration into Business Processes Based on the Requirements of Employers—Approach for Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Future of Jobs Report 2023; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2023.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2023).