Abstract

COVID-19 presents a completely new educational setting requiring teachers and students to adapt psychologically, emotionally, and physically. In kindergarten schools, this impacted teachers’ perspectives and intentions to implement play-based learning. Through a mixed approach involving 216 teacher responses and seven face-to-face interviews with school administrators, the study examines Kurdish teachers’ views on play-based learning in kindergarten schools. According to the findings, teachers’ perspectives on students’ trust in their peers, instructional leadership, and self-efficacy positively influence their behavioural intentions to implement play at kindergarten. A crucial finding of the study is validation of the positive moderating effects of teachers’ self-efficacy perspectives of students’ trust in their peers on the interactive connection between instructional leadership and play-based learning. Using classroom-based PBL, we describe play as a means of educational learning, play as a means of emotional and social development, and play as an integral aspect of learning. In the context of education changes caused by the pandemic, the findings underscore the importance of teachers assuming a leading role under learning and teaching circumstances, an enabling role in fostering associations among students and an afforded role when focusing on learning processes. Consequently, the possibilities of developing teachers’ critical feedback and reflective practices on their teaching methods are conceivable. Based on these findings, teacher education programs should emphasize theoretical understanding of play and learning as well as modelling playful teaching and play within the classroom to develop teachers’ psychological and pedagogical thinking.

1. Introduction

Globally, play-based learning has become a key element of early childhood education. It is increasingly expected that teachers will develop activities in alignment with curriculum requirements to provide optimal play experiences for children as part of play-based learning (PBL), an integral part of children’s lives. PBL is an educational paradigm that holds promise as both a resource and a source of issues. Its child-centric approach empowers learners to take charge of their education, fostering skills that extend beyond the classroom. While it embodies the spirit of child-centred learning, fostering creativity and problem-solving skills among young learners, it is not without its complexities and nuances. The implementation of PBL can also pose challenges, including managing group dynamics, adapting to remote learning, and ensuring effective assessment methods. Though studies widely reckon that play-based learning is a developmentally appropriate practice for children [1,2,3,4], maintaining a psychological, developmental, and balanced curriculum proved to be a daunting task for teachers. With the prevalence of the pandemic having altered the psychology of learning methods and psychological practices [5,6,7], it is undoubtedly evident that the implementation of play-based learning leaves so much to be desired. Additionally, with the pandemic’s adverse effects having caused education to become one of “the social arenas that have faced the most significant difficulties without being adequately equipped” [8], directing attention to PBL can help satisfy longstanding kindergarten teaching debates.

Meanwhile, the Kurdish region spans several countries, including parts of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria. Each of these countries has its own political dynamics, policies, and regulations, making research coordination and data collection complex. The Kurdistan Region of Iraq, known for its rich cultural heritage and a resilient spirit, is also home to dedicated educators who have navigated the ever-evolving landscape of education during the challenging times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Alternative, Iraqi Kurdistan, as a distinct region, offers a unique educational context that is influenced by its cultural, linguistic, and historical factors. As such, the educational landscape in Erbil, Kurdistan, differs in several aspects from other regions, including curriculum design, teaching methods, and educational policies. Erbil, known for its rich cultural heritage and a resilient spirit, is also home to dedicated educators who have navigated the ever-evolving landscape of education during the challenging times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Kurdish teachers’ experiences and the viewpoints of kindergarten students in Erbil, Kurdistan, are central to our investigation, as they bring a unique cultural and educational context to the study. In this unique context, our study explores how Kurdish teachers’ perspectives intersect with their behavioural intentions regarding PBL in kindergarten schools. By delving into Kurdish teachers’ perspectives, we seek to understand their attitudes, beliefs, and motivations concerning PBL in the context of remote or hybrid teaching necessitated by the pandemic.

Paradoxically, although there have been many studies on children’s play, few have specifically focused on teachers’ behavioural drivers of play implementation in kindergarten schools within the educational changes caused by the pandemic [3,4,9]. In some areas of educational studies, PBL has been somewhat overlooked, leaving a gap in our understanding of its efficacy and impact. The pandemic, on the other hand, revealed that PBL is not just driven by innovative learning methods [4] and student support [3], but is rather a combination of psychological and behavioural factors that, notwithstanding some valuable scholarly contributions [10], have been mostly overlooked by academia. There is still significant interest in noting that teachers’ views on educational reforms are value-laden. Hypothetically, it can be posited that their intentions and motivations to implement their respective PBL methods and practices, particularly amidst the challenges posed by the pandemic, would exhibit significant variation owing to their beliefs regarding learning and teaching, as well as their expectations and perceptions of school conditions. Hence, if we were to consider implementing PBL within the educational changes prompted by the pandemic, one could argue that it would necessitate motivating teachers to adapt their psychological and pedagogical practices. Our study seeks to bridge this gap by shedding light on the experiences and perspectives of Kurdish teachers who have embraced PBL during these unprecedented times.

Within the global educational community, PBL remains a subject of active exploration and research. As we embark on this journey, we join the ranks of scholars and educators committed to unravelling the intricacies of PBL in various contexts, each with its own unique challenges and opportunities. Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of our study lies in the uncharted territory of teachers’ motivations. To date, PBL has seldom been understood through the lens of teachers’ intentions and aspirations. For instance, Zheng, Yin, and Li opine that instructional leadership and school conditions are the key determinants shaping teachers’ perspectives and motivation to implement PBL [11]. In another instance, Zheng, Yin, and Li listed a trustful culture as a major influencing factor [12]. Although, Cheng and Chiou acknowledged the importance of other perspectives concerning teachers’ sense of self-efficacy in adopting developmentally appropriate practices, the combined interactions of these variables have been quantitatively sidelined [13]. These challenges have been significantly underpinned by the excessive use of interviews [2,3] and observations [3,9,14,15], thereby neglecting the vital role of modelling behavioural intentions, especially in the context of teachers’ perspectives. Despite Yin, Chi Keung and Yi Tam’s having shed insight into possible interactive connections linking these perspectives to behavioural intentions, the direct influence of trust in peer perspectives and the moderating effects of teachers’ self-efficacy on the role of instructional leadership and on teachers’ behavioural intentions to implement PBL had remained unexplored [4]. This ‘short circuits’ curriculum decision-making and educational policy formulation initiatives. Our research endeavours to unveil the driving forces behind why Kurdish teachers choose to embrace PBL, revealing the intricate interplay of passion, commitment, and adaptability within the educational sphere. Amid such discoveries, the study addresses these identified empirical gaps by examining the implementation of PBL within online learning methods introduced during the pandemic. Thus, the current study is designed to satisfy the following research inquiries:

- What are the teacher’s perspectives regarding students’ trust in their peers, teacher self-efficacy, and instructional leadership factors in determining whether play-based learning will be implemented in kindergarten schools?

- How have kindergarten school children responded to the implementation of PBL since shifting to online learning methods and practices during the pandemic?

By examining teachers’ motivations to undertake PBL, our research extends beyond the classroom. We touch upon critical aspects of educational leadership and, surprisingly, teachers’ perceptions of the mutual trust that forms the cornerstone of effective teaching and learning. Primarily, the study advances Bronfenbrenner’s bio-ecological model by filling contextual empirical gaps regarding the time and situation in which play-based learning is being implemented amid the devastating psychological effects of the pandemic on learning methods and practices [5,6,7] and testing current empirical evidence [1,4]. A crucial finding of the study is the positive moderating effects of teachers’ self-efficacy perspectives of students’ trust in their peers on the interactive connection between instructional leadership and PBL. Our research’s contributions lie in its capacity to extend, develop, and validate prior studies’ robustness in yielding the precise, reliable, and sound ideas essential for curriculum decision-making and educational policy formulation.

2. Literature Review

The integration of behavioural analysis concerning the interactive connections linking play-based learning with teachers’ perspectives is still lacking and commands significant empirical attention. It is, therefore, the purpose of this section to review related papers and identify research gaps.

2.1. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory

While Parten’s social behaviour theory and Piaget’s cognitive development theory can be deployed in the PBL debate, the relevance and significance of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory are worthy of consideration. There is a strong correlation between Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory and this context, as it describes the influence of multiple environments, including the classroom, children’s beliefs, culture, and community, as well as the effects of timing and environmental events, such as the pandemic and educational policies, on children’s play [16,17]. Consequently, it is enlightening to find that the combined interactive influence of these factors had a significant toll on teachers’ perceptions and behavioural intentions to implement PBL amid a surge in COVID-19 cases and rising calls to shift towards online schooling [5,6,7]. Furthermore, to the researchers’ knowledge, studies addressing variations in behavioural intentions concerning teachers’ perceptions are still in their infancy. This clouds judgement about the implementation of PBL, especially in kindergarten schools. Most importantly, we believe not much has been done to determine how the propositions of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory translate into perceptions that influence behavioural intentions. Therefore, the study’s contributions are engraved in its integration of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory. This integration establishes a framework essential for analysing interactive connections between teachers’ perceptions and behavioural intentions.

Meanwhile, through his ecological theory, Bronfenbrenner recognises the influence of multiple environments on children’s play and how they will grow and develop [16]. Bronfenbrenner further unveils that the immediate environment, known as the microsystem of the child’s family, influences children’s play [16]. These effects are weighed by teachers when deciding on the type and integration of PBL methods and practices, thereby influencing their perceptions and behavioural intentions. With both perceptions and behavioural intentions embedded in such acts, the call for studies to further uncover additional connections and the nature of influences remains relatively high. In any case, the existence of other channels of influence can be unveiled following what Bronfenbrenner terms the macrosystem, which is a combination of cultural and social values [17]. It is imperative to note that children’s beliefs, culture, and communities influence their play. The resultant effects are on how children interact with their peers and teachers [17] and demonstrate their behaviour and attitude towards PBL methods and practices [16]. Consequently, teachers’ perceptions of students and PBL’s implementation and practices affected by the macro system become one of the chief factors they utilise in deciding which, when, how, and when to implement PBL. Though teachers and family influence children’s play [3], recognising similar effects posed by the chronosystem is also worthy of consideration. This is because changes in the timing of events and the environment over time influence children’s play as evidenced by changes and the adoption of online learning methods and practices amid the widespread effects of the pandemic [5,6,7]. Overall, an analysis of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory exhibits numerous channels through which teachers’ perceptions and behavioural intentions to implement PBL methods and practices during the pandemic are affected. Hence, this study uses Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework along with prior related studies when modelling new teacher-perceptions and behaviour-related variables in PBL.

2.2. Learning through Playing

Drawing insights from Rao and Li [18] and Hyvönen [9], it can be determined that play can be broadly defined and characterised by indoor and outdoor activities involving playing with objects, pretending games, and social games for entertainment and developmental purposes. Consequently, play is an essential activity whose integration with learning methods and practices yields significant improvements in students’ ability to comprehend ideas and tasks [11], interact with other students [15] and affect educational performance [19]. As such, teachers can elicit such benefits by tapping into structured games, fantasy play, constructive play, social play, and physical play. However, another body of studies asserts that, in certain instances, play is perceived as unimportant [4,20] and associated with harmful practices [21]. As a result, such a lack of consensus creates avenues for teachers’ perceptions to diverge and trigger differences in their behavioural intentions to implement PBL. Despite such an observation carrying tremendous relevance in contemporary educational contexts, its coverage in studies remains mostly unexplored. For instance, Yin, Chi Keung and Yi Tam cite the influences of perspectives in governing both students’ and teachers’ conduct and approaches to educational settings [4]. But recognising that the influences of perspectives on students’ and teachers’ conduct and approaches are transmitted through channels and ultimately reflected through variations in behavioural intentions has not been the common focus. Moreover, the high prevalence of the pandemic suddenly forced students and teachers to accustom themselves to new online learning methods and practices they were not accustomed to [5,6,7], one may assert that teachers’ perspectives and behavioural intentions towards PBL were evidently affected. The pedagogical and curriculum implications of such effects can have a profound effect on learning methods and practices, students’ approaches to study and behaviour towards learning as well as educational performance if proper action and strategies are not taken to realign PBL with the newly incorporated learning methods and practices. Hence, this places a huge demand for studies to explore factors which contribute to the implementation of play-based learning within the educational changes caused by the pandemic.

Within the context of the pandemic, PBL including free play, guided play, and games, was noted as having been implemented far less frequently during the pandemic than before [22]. However, Ellis further observed that the pandemic influenced kindergarten teachers’ presence, desire, and ability to implement PBL. As a result of observations made, noting that little attention has been paid by policymakers to children’s lost opportunities for play [23], the desire for and feasibility of PBL gain huge credence. Spadafora and others’ findings highlight that there are unique challenges associated with teaching kindergarten during the pandemic, contributing to our understanding of the learning that occurred during COVID-19 [24]. This further demands studies to be conducted within the context of other kindergarten schools in other countries like Kurdistan.

Meanwhile, Hyvönen outlines that future PBL activities in education will continuously demand teachers to think about learning activities that challenge and motivate students to learn and perform better [9]. Games, together with play, are instrumental in promoting learning [1] and fostering development [11]. However, teachers’ strategies and attitudes concerning play have been conceived as varying significantly in this regard [9,19,21]. The rationality of implementing play is widely documented in educational studies, which provide justifications pointing to physical, social, emotional, and cognitive benefits [11,25,26,27]. Another line of studies pinpoints that benefits such as reforming students’ and their peers’ cultures are attributed to the implementation of PBL methods and practices in schools [28,29,30]. Prior research by Moyles indicated that play offers mutual learning opportunities for students and teachers [31].

The influence of perceptions on teachers’ behavioural intention to implement PBL should not be eluded. For instance, Yang and Chen cite that teachers view PBL not only as a real learning medium but also as a means to optimally discern and gain knowledgeable information about students and their needs [30]. Yang and Chen remark that these capabilities are highly coveted and consequently motivate and persuade teachers to implement PBL. Concurrently, Moyles revealed that deploying PBL learning methods is instrumental in enhancing teachers’ understanding of students’ learning and general development conditions [31]. Under such cases, teachers’ ability to introduce new learning methods and practices in the affective and cognitive domains becomes highly feasible. Thus, such aspirations drive them to implement PBL and that clarifies the motives behind behavioural intentions to implement PBL in schools. Moreover, with ideas about self-regulation being highly linked to early children’s development [9,11,32], teachers are more inclined to implement PBL so as to allow students to organize their learning. Additionally, another line of studies contends that self-regulation provides students with an ability to plan, monitor their success, and correct their behaviour where necessary, hence, the tendency to implement PBL in schools arises. Additionally, while Yang and Chen [30] reckon that PBL forms part of the mechanisms that are used to give students opportunities to simultaneously play and learn at the same time, Zheng, Yin, and Li [11] state that PBL accords teachers with more opportunities for reflection.

Hence, this section of the literature establishes a clear connection linking PBL’s benefits and its influence on teachers’ behavioural intentions to implement it. However, little has been done to determine the nature of perspectives triggering the need for PBL as well as motivating and persuading teachers to implement it in schools. With Zheng, Yin, and Li acknowledging that aspects such as instructional leadership impose a significant toll on teachers’ ability to lead and implement curriculum reforms [11], there are numerous and possibly varying perspectives about instructional leadership’s influence on the implementation of PBL in schools. This is of notable concern, especially bearing in mind that Bransford, Brophy, and Williams maintain that play enhances students’ ability to effectively learn to utilise numerous strategies like conceptualizing, reasoning, and solving problems [33]. Of paramount importance are discoveries by Pyle, Poliszczuk, and Danniels, revealing that students can amass significant conceptualizing, reasoning, and problem-solving abilities when encouraged by their teachers to adopt the role of an expert during play [34]. However, this does not account for the vital influence of teachers’ expertise and confidence. With both teachers’ expertise and confidence, being combinedly defined as teacher self-efficacy [35], it remains an interesting line of inquiry that teachers’ perspective on their self-efficacy significantly influences their intentions to implement PBL in schools. Amid such discoveries, it is imperative to note that students’ trust in their peers has a significant influence on their learning abilities and those of other students as well, but the interactive effects of such influences on teachers’ behavioural intentions to implement PBL remains to be documented. It is in this regard that this study adds knowledge to the long-standing PBL debate. Thus, the influence of teachers’ perspectives about students’ trust in their peers, and their instructional leadership as well as self-efficacy have a huge effect on their behavioural intentions to implement PBL. The importance of such efforts is underpinned by studies underscoring that learning through play is the embodiment of and combines numerous higher cognitive activities such as reflecting, perceiving, reasoning, and thinking with physical actions [36]. This aligns with Price and Rogers’ DuBose and others’ insights reiterating similar views and highlighting that physical actions are instrumental for students’ well-being and educational achievement and should be applied across the curriculum [36]. Thus, along Hyvönen’s perspectives, PBL is not only a cognitive process but rather a collection of physical, social, emotional, and cultural processes with a significant effect on teachers’ perspectives about students’ trust in their colleagues, and their instructional leadership as well as self-efficacy [9]. Therefore, it is vital at this juncture to establish that a solid understanding of the role and benefits of play in kindergarten schools requires the integration of teachers’ perspectives and behavioural intentions that vary within the educational changes, especially those caused by the pandemic. Hence, the need to attach and analyse the influence of teachers’ instructional leadership, trust in peers, and teacher self-efficacy.

2.3. Behavioural Analysis: The Intention to Implement PBL

Given that the above examinations have revealed that teachers’ behavioural intentions to implement PBL in schools are, to a large extent, driven by their views on students’ trust in their peers, and their instructional leadership as well as their self-efficacy, this section of the study is designed to determine the exact manner of connections linking these perspectives to behavioural intentions. Consequently, our hypotheses were formulated as follows:

2.3.1. The Impact of Teachers’ Perspectives of Students’ Trust in Their Peers on Behavioural Intentions

Despite some studies placing a huge focus on the role of PBL in schools [28,29,30], teachers’ intentions to implement PBL in schools are subject to the influence of perspectives and numerous group dynamics and school cultural factors. For instance, in Canada, Lynch discovered that prioritising play-based methods compared to teacher-led activities with clear deliverables is perceived as lazy [37]. Along similar lines, we argued that trust in peers serves as a classroom drive which facilitates teachers’ motivations to implement play-based learning in kindergarten classrooms.

Meanwhile, the importance of trust is widely documented in educational studies. For instance, Van Maele, Houtte and Forsyth view change implementation as primarily driven by trust [38]. Vostal, LaVenia and Horner saw trust as instrumental in fostering interactions and collaboration among students while outlining that trust influences students’ effective ability to learn from one another through effective reciprocal communication [39]. Amid several cultural differences influencing the transfer and sustenance of knowledge gained [40], play requires trust and cooperation among students. Hence, it is apparent that a lack of trust among students hinders the effective use of PBL learning methods and practices. The relevancy of such notions carries huge empirical weight when observations are made that a lack of trust instils negative energy and a sense of resistance among students [12], demotivates students [39], hinders the exchange of information between students [26], slows teachers’ progress [38], and corroborates Bronfenbrenner’s ecological propositions highlighting the influence of children’s beliefs on learning and teaching methods [16]. As a result, teachers’ negative ideas about students’ trust in their peers restrict their motivations to implement play in schools because of the high risks involved. With limited investigations examining these interactive connections amid changes posed by the pandemic, the following hypothesis was formulated;

Hypothesis 1.

Teachers’ ideas of students’ trust in their peers positively influence behavioural intentions to implement play-based learning.

2.3.2. The Impact of Instructional Leadership Perceptions on Behavioural Intentions

According to Blase and Blasé, instructional leadership is a blend of several tasks including supervision of classroom instruction, staff development, and curriculum development [41]. Zheng, Yin, and Li defined instructional leadership in the context of teachers’ ability to define clear standards for instructional practices [11]. Hence, by implication, instructional leadership is a chief classroom antecedent of teachers’ motivations to implement PBL. Moreover, prior studies have highlighted that instructional leadership forms a critical part of attempts to create a supportive learning environment among teachers, guide teachers, and offer them constructive feedback to improve their teaching [4,11,42].

In line with Zheng, Yin, and Li’s discoveries, instructional leadership is deemed as playing a vital role in creating a supportive culture and learning environment, enhancing teachers’ instruction, and implementing curriculum reforms [11]. Yin, Lee, and Jin reckon that instructional leaders play an instrumental role in nurturing an open and trusting climate, which is essential for making teachers feel comfortable [27]. Concurrently, Zheng, Yin, and Li pinpointed that instructional leaders themselves play an instrumental role in redesigning curriculums so that they adhere to the reform requirements and the expectations of various stakeholders such as children, parents, and teachers [11]. As a result, it becomes relevant to explore whether school administrators in kindergarten schools are motivated to use their leadership to influence teachers’ behavioural intentions to implement innovative pedagogies like PBL. In schools, teachers are much more likely to derive significant levels of satisfaction from instructional leaders and, therefore, be motivated to implement PBL methods and practices. In the contemporary educational environment, which is characterized by numerous changes in learning that have been triggered by the pandemic, such attributes carry a great deal of empirical significance. However, this remains to be tested and it is in this regard that the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 2.

Ideas about instructional leadership positively influence behavioural intentions to implement play-based learning.

2.3.3. The Impact of Teacher Self-Efficacy Perceptions on Behavioural Intentions

Teachers’ efficacy has a hugely important bearing on their intentions to implement PBL in schools as it is intertwined with numerous essential competencies and attributes such as beliefs [34], expertise [43], and confidence [44]. Consequently, this places a huge demand to boost teachers’ efficacy, especially when implementing educational changes such as transitioning to online learning during the pandemic [45]. Bandura’s prior establishments reveal that self-efficacy can be defined as the perceived capability of an individual to execute a specific action [46]. Bearing in mind Bandura’s insights, this study extends such notions in developing arguments contending that teacher perceptions of self-efficacy have a significant impact on behavioural intentions to implement play-based learning. With little empirical evidence establishing a direct connection between teacher perceptions of self-efficacy with behavioural intentions, our empirical examinations apply Bronfenbrenner’s theoretical ideology in covering such empirical voids. With Bronfenbrenner stating the influence of multiple environments, classrooms, children’s beliefs, culture, and community, as well as timing and environmental events like the COVID-19 pandemic and educational policies on children’s play [6,40], the influence of teacher self-efficacy perceptions in this context, is highly conceivable.

Dating from Tschannen-Moran and Hoy [26] to Louis, Dretzke, and Wahlstrom [42], teacher self-efficacy has been revealed as having an instrumental positive influence on teachers’ devotion to improving students’ learning and development and commitments to teaching. Another line of studies explains that teacher self-efficacy is linked to improvement in student achievement [47], engagement in school improvement [25], perceptions of the reform of outcomes, and commitment to teaching [19], supporting students’ learning [21], and beliefs or confidence to positively influence students’ learning [4]. Nonetheless, there is a dearth of research exploring the interactive effects of teacher efficacy on teachers’ intentions to implement PBL, eliciting the need for the present study. Additionally, the prevalence of moderating situations posed by the influence of students’ trust in their peers and self-efficacy on the interactive connection between instructional leadership and the implementation of PBL has been ruled out in several instances [3,4,9]; thus, clouding judgements and demanding further clarification. In that regard, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 3.

Ideas about self-efficacy positively influence behavioural intentions to implement play-based learning.

Hypothesis 4.

Ideas about students’ trust in their peers positively moderate the interactive connection linking instructional leadership and the implementation of play-based learning.

Hypothesis 5.

Ideas about self-efficacy positively moderate the interactive connection linking instructional leadership and the implementation of play-based learning.

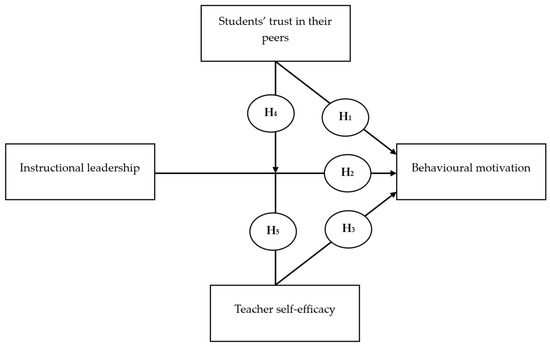

Following the establishment of limited attempts to explore the influence of teachers’ instructional leadership, students’ trust, and self-efficacy perspectives on their behavioural intentions to implement PBL within the educational changes caused by the pandemic, a conceptual framework shown in Figure 1 was developed. Figure 1 shows interactional influences connecting instructional leadership, trust in peers, and teacher perspectives on self-efficacy with behavioural intentions. Thus, the influence of trust in peers on behavioural intentions, underpinned by the behavioural theory, is delineated by the arrow streaming from trust in peers to behavioural intentions as assumed in H1. H2, and H3; representing the effects of trust in peers and teacher self-efficacy on the teachers’ behavioural intentions. The influence of trust in peers and teacher self-efficacy on the interactive connection linking instructional leadership with behavioural intentions represents the moderating effects of trust in peers and teacher self-efficacy as hypothesised by H4 and H5.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Methodology

The application of the mixed approach holds significant empirical grounds in educational studies. For instance, drawing on Leavy’s ideas, benefits such as enhanced data triangulation, methodological triangulation, contextualization, comprehensive understanding, enhanced validity and reliability, and policy and practice implications were listed as conceivable for applying a mixed research approach [48]. Additionally, Mulisa agreed that mixed research acknowledges integration as active and reflective relationship building, which encompasses the whole research process and involves a variety of relations and interrelations [49]. That is particularly relevant in contemporary education settings because they are characterised by increased complexities, such as COVID-19 [45] or the researchers’ experiential and cultural biases [50]. Despite its contribution to effective implementation of PBL methods and practices, ecological theory has not yet been fully integrated with the educational changes resulting from the pandemic in Erbil kindergarten schools. Further, research on related topics is overwhelmingly focused on countries such as the United States [17], New Zealand [51], China [4], and Iran [44], leaving countries like the Kurdistan Region of Iraq out of the discussion. Considering these observations, related studies have been reviewed in relation to Bronfenbrenner’s proposals for defining new forms of teacher perceptions of variable constructs and evaluating their impact on PBL motivation. As a result, kindergarten teacher surveys, observations on kindergarten students, and interviews with kindergarten school administrators were applied in the context of private kindergarten schools in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq.

3.1. Participants and Data Collection

Data were collected using two distinct methods involving interviews and surveys. Recognising differences between private and public kindergarten schools, the study assumes the existence of potential differences in the nature and extent to which teachers at the respective schools implement play-based learning. Instead of both private and public kindergarten schools using PBL methods, it is to the researchers’ knowledge that, regarding the level and nature of PBL activities and methods used in Erbil, which is located in Iraqi Kurdistan, private kindergarten schools outweighed public kindergarten schools. In that regard, our motivation and justification to explore Kurdish teachers’ ideas of play-based learning were highly called for. Therefore, the study involved an examination of five private kindergarten schools in Rawandz, in the countryside near Erbil, the Hawler Center, Shaqlawa, and Koya districts within Erbil city, located in Kurdistan. These schools were selected based on criteria including geographical location, offering full-day kindergarten programs, and their willingness to participate in the research project. Prior to data collection, this research received clearance from the Research Ethics Board of Near East University and the directors of participating schools.

Apart from accessibility, convenience sampling was applied because it provided an opportunity to gain insights from teachers and school administrators who are directly experiencing and adapting to these circumstances. Their perspectives can provide valuable contextual understanding of the unique cultural and educational context of Kurdish kindergarten schools during COVID-19.

First, recognizing that the adoption of PBL plays a crucial role in enhancing the development of students’ social and emotional skills [9], academic performance [19], problem-solving and conflict-resolution abilities [15], and communication skills [11], questionnaires were administered to a diverse group of teachers in kindergarten schools. The selection criteria included teachers with varying levels of educational qualifications and teaching experience, representing a mix of backgrounds and expertise. This approach allowed the study to investigate whether a range of teacher qualifications and experience levels influenced the effective adoption of PBL methods and practices in kindergarten schools. By comparing high-performing teachers to less effective or less experienced teachers, we can identify factors contributing to their success. Consequently, we produced and administered by hand 216 questionnaires to kindergarten teachers meeting this criterion from the 7th of September to the 23rd of October 2022. All teacher respondents completed the survey.

Secondly, 7 face-to-face interviews with school administrators were conducted to allow for in-depth discussions, where administrators could provide nuanced and detailed insights. This method enabled researchers to explore complex issues, policies, and decision-making processes within the school environment more comprehensively than other data collection methods. By combining teachers and administrators’ data elements, our study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of PBL practices on students’ learning outcomes and experiences. The interconnectedness of these data sources allows us to draw robust conclusions about the effectiveness of PBL in the kindergarten setting while considering the multifaceted perspectives and contextual factors at play.

3.2. Variables and Operative Implementations

The variable teacher self-efficacy perspectives comprised classroom management, child engagement and instructional strategy dimensions with a total of 12 questions. Additionally, 7 trust in peers, 7 instructional leadership, and 4 behavioural intention perspectives questions were also incorporated into the questionnaire. These variables were measured on a 5-point Likert scale corresponding to 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Recognising emerging behavioural intention, students’ trust in their peers, teacher self-efficacy, and instructional leadership variable constructs were previously applied and already validated in the context of 542 Hong Kong kindergarten teachers, our study extends, develops, and weighs Yin, Keung and Yi Tam’s variable constructs in the context of 216 Erbil kindergarten teachers [4]. To ensure that questions were culturally appropriate and culturally sensitive, we translated them from English to Kurdish. The translated questions were pilot tested with a small group of Kurdish-speaking individuals to determine their clarity and comprehensibility. Finally, we reviewed the translated questionnaire for any typographical errors, grammatical issues, or inconsistencies.

In addition to being easy to use and versatile, a Likert scale was used to provide a standardized approach for measuring perceptions, opinions, and attitudes on a specific topic. A “Likert crush” was avoided by providing clear and concise instructions to respondents about how to complete the Likert scale, conducting pilot tests, presenting statements in a randomized order to mitigate response bias resulting from the sequence of questions, and avoiding leading questions.

Lastly, semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted with school administrators. The interviews were approximately 10 min in length and focused on school administrators’ perspectives on the purpose of play in a kindergarten classroom. They also focused on how PBL was integrated into teachers’ programs.

3.3. Data Analysis

The observed PBL activities and the collected school administrators’ interview responses were analysed using a qualitative research approach involving the application of deductive reasoning inferences made in line with existing PBL theoretical frameworks, concepts, and empirical studies. Related studies on teachers’ perspectives are broadly concentrated on the application of interview-based data collection methods [2,3,18,32,52] and there is lack of validation of estimated empirical models, notably structural equation modelling [4]. Because of that, we applied a structural equation modelling (SEM) approach built on the developed conceptual model provided in Figure 1. The application of the SEM approach in this study provided an avenue allowing the simultaneous testing of relationships between instructional leadership, trust in other peer students, teacher self-efficacy perspectives and motivations. A decision to deploy SEM is also empirically justified in educational studies since the development of best-fitting models and theories [53], the assessment of measurement error [54], and model testing based on imposing a structure and evaluating whether the data fit has been demonstrated [55].

Smart PLS was used to analyse the 216 collected kindergarten teachers’ responses. Cronbach’s alpha test was performed in analysing the variable constructs’ internal consistency under the conception that variables with alpha values of 0.70 exhibit high reliability [56]. Along similar lines, composite reliability was ascertained [56]. The nature of the model’s exact discriminant and convergent validity conditions was respectively, assessed using the multigroup Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) test [57] and average variance explained (AVE), demanding that the computed AVE values surpass the required 0.50 benchmark [56,58].

The estimated structural equation model was subjected to model fitness tests comprising the utilization of the Chi-square statistic (χ2) demanding a significant Chi-square statistic (χ2), value, a standard root mean square residual (SRMR) value of less than 0.08, NFI values exceeding 0.90 and D_G and D_ULS that were lower than the related confidence interval [56,57,58].

4. Findings

4.1. Survey Findings

4.1.1. Demographic Analysis

All the teachers responded to the survey and, according to Table 1, participants significantly differed (ρ = 0.000) in terms of the number of male teachers (n = 139) and female teachers (n = 77) involved and denotes variations in professional preferences between male and female individuals. Along with efforts expended towards establishing the influence of educational qualifications, the study identified that 88.89% of the selected kindergarten teachers held bachelor’s degrees and 10.65% master’s degrees, while 0.46% had PhD degrees.

Table 1.

Model variables and dimensions.

4.1.2. Factor Analysis, Formative and VIF Indicator Results

Table 2 shows the measured variables together with their respective dimensions: number of selected items, factor loadings, outer weights, and variance inflation factor (VIF). As per Table 2’s findings, only variable constructs with factor loadings of at least 0.60 were selected and deemed as related and conceptually significant [49]. By using the selected constructs, convergent validity was established at 1% as denoted by outer weights formative indicators. Furthermore, the VIF values are less than 3, indicating that there were no multicollinearity issues associated with the selected variables. Amid such observations, the researchers were well poised to infer valid interpretations of the Kurdish teachers’ ideas on play-based learning in kindergarten schools during COVID-19.

Table 2.

Factor analysis, formative and VIF indicator results.

4.1.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Coefficient

Descriptive statistics were deployed to analyse the 216 collected kindergarten teachers’ survey responses. As per Table 3′s presentation, the findings illustrate that on a five-point Likert scale, teachers’ self-efficacy had a mean value of 4.05 with SD = 0.784 means, MIN = 3.266, and MAX = 4.834, which is relatively higher than the mean score of 3.81 established with SD = 0.482 means MIN = 3.328 and MAX = 3.863 on a similar Likert scale [4]. Such findings imply higher or stronger agreements concerning the selected Kurdish kindergarten teachers’ high self-efficacy. Table 3 further exhibits relatively higher indication of agreements among the teachers concerning students’ trust in their peers (M = 4.76) and instructional leadership (M = 4.62) perspectives of PBL, with higher indications being linked to behavioural intention (M = 3.81). Ideas concerning the influential roles of teachers’ perceptions about students’ trust in their peers, self-efficacy and instructional leadership perspectives of PBL could not be refuted as evidenced by the respective significant positive correlations of 0.602, 0.612, 0.633, and 0.719.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficient.

4.1.4. Discriminant and Convergent Validity, and Composite Reliability Tests

Discriminant and convergent validity and composite reliability tests were applied prior to interpreting the estimated model with the aim of ascertaining the model’s capacity to infer valid and reliable insights into the kindergarten teachers’ perspective of PBL. As per the HTMT criterion, the HTMT values exhibited in Table 4 are below 0.90 and this indicates that discriminant validity was established among the selected variables.

Table 4.

HTMT results.

In line with Table 5′s findings, we inferred and upheld that convergent validity existed among the model variables as their related AVE values surpassed the required 0.50 benchmark [56,58]. Furthermore, this is reinforced by the outer weight results shown in Table 1.

Table 5.

Discriminant validity and reliability results.

The teachers’ PBL perspective variables were highly reliable as evidenced by their related Cronbach’s alpha values (BI: α = 0.940; TIP: α = 0.972; TSE: α = 0.948 and IL: α = 0.956) that exceeded the stipulated benchmark of 0.70 [59]. Such high internal consistency is relatively higher than the respective values obtained in Yin, Keung, and Yi Tam’s study (BI: α = 0.935; TIP: α = 0.971; TSE: α = 0.934 and IL: α = 0.952) and adds empirical weight to unvalidated studies [4].

Drawing further, in line with Ringle, Da Silva, and Bido’s propositions, high compositive reliability was established as evidenced by both the rho_A and composite reliability values that are higher than the stipulated 0.70 cutoff value [56]. Consequently, it is in this regard that we upheld inferences that the study model is well-poised to confer valid and reliable inferences about teachers’ perspectives on PBL in Kurdistan’s kindergarten schools, which has not been the case with related examinations [3,4,9].

4.1.5. Model Fitness Tests

Following the successful establishment of the model’s discriminant and convergent validity, and composite reliability, we proceeded further to ascertain the model’s fitness. Amid such attempts, we discovered that the model exhibited features of an acceptable fit as supported by the computed NFI values exceeding 0.90 [58], a Chi-square value of 32.220 that is significant at 1% [56], D_G and D_ULS that were lower than the related confidence interval [57], and an SRMR value of 0.063 that is below 0.080 [56,58], as presented in Table 6. This indicates that the estimated teacher perspectives model is perfectly fitted and free from misspecifications issues.

Table 6.

Model fitness tests.

4.1.6. Path and Moderation Analysis Results

Given that the estimated model has been proven to be well-poised to yield robust, consistent, valid, and reliable insights into the kindergarten teachers’ perspective of PLBL, the study proceeded further to interpret the path analysis results. In that regard, the positive interactive effects of the teachers’ perspectives about PBL’s enhancements of the students’ trust in their peers were upheld (β1 = 0.395; ρ = 0.000; R2 = 0.45), as denoted in Table 7.

Table 7.

Path and moderation analysis results.

The positive influences of instructional leadership (β3 = 0.487; ρ = 0.001; R2 = 0.567) and teacher self-efficacy (β2 = 0.562; ρ = 0.025; R2 = 0.487) on motivation were confirmed as significantly valid in the context of kindergarten teachers in the city of Erbil in Kurdistan. Thus, 44.6.7%, 56%, and 48.3% are good enough to establish the model’s predictive relevance. The findings presented in Table 7 also confirmed the prevalence and significance of positive moderating influences posed by trust in peers (β4 = 0.141, ρ = 0.010) and teacher self-efficacy (β5 = 0.195, ρ = 0.000) on the interactive connection linking instructional leadership with behavioural intention. Consequently, hypotheses four and five were accepted.

4.2. School Administrators’ Interview Findings

Inferences drawn from the interview results converged into three distinct categories of classroom-based approaches to PBL, as depicted in Table 8. As such, it was commonly observed that the administrators viewed play as an instrument for educational learning. As indicated by responses like, “play is specifically designed to support the learning of targeted educational skills”, (P2); “play gives students’ opportunities to practice what they have been taught”, (P4); and “most teachers reported that students voluntarily engaged in other types of learning when play methods are applied”, (P7). As a result, the integration of play took two forms: teacher and student-constructed contexts of play, and teacher-modelled and child-led play. Following this, the administrators’ findings indicate that teachers have a primary responsibility to promote discussions, introduce ideas, and extend students’ learning.

Table 8.

Emerged themes in school administrators’ responses.

The themes derived from the interviews show that school administrators require or encourage kindergarten school teachers to utilise play as an avenue for emotional and social development. In that regard, as illustrated in Table 8, the administrators consider that teachers’ main objective, in this case, is to promote independently motivating tasks and interactions. Thus, it is inferred that implementing the desired approach involves utilizing structured social problem-solving methods and tools, providing unrestricted access to resources like manipulatives and toys, and incorporating child-led play strategies. Accordingly, these findings suggest that teachers’ roles in this scenario should be centred on modelling and supporting social problem-solving techniques.

Based on the third category, play as a peripheral element of learning, the findings identify actions that can be taken to meet school administrative standards, encourage collaboration among teachers, and cover the entire curriculum. This can be seen in interview responses such as “play yields desired results when acceptable standards are followed”, (P1) and “teachers must work together to gather information and design the best PBL teaching methods and practices”, (P2). Overall, both types of participants provided responses indicating that the main objective of using play is to give students a break from educational learning. Following these findings, inferences must be drawn pointing to enactment as a result of teacher-constructed and child-led play strategies. As a result, it is required, as depicted in Table 7, that teachers assume responsibilities concerning the monitoring and supervision of student behaviour. Because of such observations, discussions of findings were undertaken to infer judgments, suggesting strategies as per study findings for curriculum decision-making and educational policy formulation purposes, and for guiding future research.

5. Discussion

By identifying and addressing empirical gaps and making significant contributions, this study develops novel ideas about the interactive influence of teachers’ perspectives on their motivations to implement PBL in schools. While the study does not directly analyse the pandemic as a factor, it underscores the importance of understanding how educational changes, possibly influenced by unforeseen circumstances like the pandemic, can impact the implementation of PBL. Accordingly, the study findings converged on a common point of view advocating that PBL must be structured according to circumstances, associations, and processes to effectively impart students with knowledge and facilitate performance improvements. This study aligns with Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory, illustrating the intricate influence of various environments, including the classroom, on teachers’ motivations. It emphasizes the centrality of the teacher within this model, acknowledging the impact of factors such as children’s beliefs, culture, community, timing, environmental events like COVID-19, and educational policies on teachers’ engagement with play-based learning. In this context, it is essential to emphasize the role of teachers as central figures in the ecological model, as posited by Bronfenbrenner. The study explores the influences on teachers’ motivations, particularly in the context of PBL, considering various factors like children’s beliefs, culture, community, timing, and significant events such as the pandemic and evolving educational policies [16,17]. What is more, studies have revealed various forms of adverse effects such as stress [60], trauma [61], depression [62], and anxiety [63] related to the pandemic. As indicated by Vélez-Agosto and others, the majority of research within the ecological framework resulted in having “conceptual confusion and inadequate testing of the theory” [64]. As a result, we formulated and tested specific hypotheses using a SEM approach based on the ecological framework. This approach enables us to empirically examine the relationships between variables, provide a robust test of the theory’s predictions and assumptions, and offer further evidence for existing research in this area.

Our study acknowledges the diverse effects of the pandemic on teachers’ perspectives and behavioural intentions to implement PBL in schools, as well as school administrators’ views PBL. These effects highlight the need for comprehensive recommendations to address the pandemic’s impact on educational practices. In light of this, our study provides recommendations that hold relevance beyond the pandemic. These recommendations draw from both survey and interview findings, aligning with suggestions made by Hyvönen [9]. Such recommendations are scantly incorporated into subsequent and contemporary examinations [1,4,14,30]. During the pandemic, it became even more critical for teachers to assume a leading role in adapting to new teaching circumstances, fostering association among students in a virtual setting, and focusing on dynamic and effective learning processes. These recommendations emphasize the significance of teacher leadership in addressing the unique challenges brought about by the pandemic and beyond. By connecting the recommendations to the pandemic’s impact and the altered educational landscape it has caused, we emphasize the relevance and applicability of the recommendations in the context of the pandemic while highlighting their broader significance. However, we emphasise, therefore, that this was conditional on the administration of inherent different forms of play-matching circumstances (physical play, cheering play, and educational play), association (free play, traditional play, authentic play, and pretend play), and processes (process play).

Along with Tschannen-Moran and Hoy’s conclusions [26], our study demonstrated that kindergarten teachers’ ideas about students’ trust in their peers have a significant positive interactive influence of 0.39 related to motivations to implement PBL. These findings have vital practical bearing on pedagogical studies, especially when contemporary studies are confined to systematic review of problem-based learning, project-based learning (PjBL), and challenge-based learning (CBL) [65]. Though applied in a different context, Sims observed insignificant positive effects of trust on educational optimism [66]. Along similar lines, Yin, Lee, and Jin viewed it as essential for the effective improvement of the school environment [27]. Thus, in such circumstances, teachers are drawn to implement PBL in schools. In light of these findings, it is clear that an increased recognition of the importance of trusting relationships, mutual learning, and information sharing between students is crucial to kindergarten teachers’ confidence in the implementation of the reform. Innovative ideas have often been overlooked in empirical studies, which have primarily focused on trust among teachers [39,44]. However, students’ trust in their peers plays a crucial role in creating a safe environment for teachers to experiment with innovative strategies. When teachers feel safe to explore new approaches, it enhances their sense of self-efficacy, subsequently positively affecting their motivation to implement play-based learning.

Yin, Keung, and Tam’s lower empirical influences of 0.333 and 0.337, respectively, were validated by hypotheses two (β2 = 0.487; p = 0.001) and three (β2 = 0.562; p = 0.025), which validated significant positive interactions between instructional leadership and teacher perceptions of self-efficacy on behavioural intentions [4]. Such results can be of instrumental value in the context of Birzeit University in Palestine, where 53% of the respondents reported that they were unaware of PBL [65]. In that context, benefits such as the transferability of insights, informing implementation strategies, tailoring educational interventions, benchmarking and comparative analysis, and resource allocation and planning are highly conceivable. Based on these findings, Zheng, Yin, and Li’s finding that instructional leadership is essential to creating a supportive culture and learning environment, enhancing teachers’ instruction, and implementing curriculum reforms is supported [11]. Along similar lines, Yin, Lee, and Jin reckon that instructional leaders play an instrumental role in nurturing an open and trusting climate that is crucial for making teachers feel comfortable [27]. Both attributes enhance PBL’s attractiveness and essentially compel teachers to implement it in schools. Additionally, our findings are consistent with the research by Tschannen-Moran and Hoy [26] as well as Louis, Dretzke, and Wahlstrom [42]. These insights underscore the vital role of teacher self-efficacy in driving teachers’ dedication to improving student learning and their commitment to effective teaching. Notably, the positive influence of teacher self-efficacy can be significantly augmented through the implementation of PBL [4,34,44]. This sets the stage for exploring the interconnectedness between teacher beliefs, instructional strategies, and student outcomes. At any event, numerous avenues through which teacher self-efficacy triggers changes in teachers’ motivations to implement PBL are conceivable. This is through educational targets linked to improvement in student achievement [47], engagement in school improvement [25], perceptions of reform outcomes and commitment to teaching [19], supporting students’ learning [21], and the belief or confidence to positively influence students’ learning [4].

The innovative concepts in this study shed light on previously unclear aspects regarding the influence of students’ trust in peers and self-efficacy on instructional leadership and PBL implementation. While prior studies [3,4,9] often dismissed the existence of these effects, our research reveals significant moderating effects, with respective values of 0.141 and 0.195.

6. Conclusions

Considering all of these explanations, this study has achieved its stated purpose by providing insight into teachers’ experiences with PBL, kindergarten students’ reactions to PBL, as well as school administrators’ perceptions of the implementation of PBL in kindergarten schools. The study findings increase understanding of teachers’ and pedagogical thinking regarding play as a learning medium within the context of education changes caused by the pandemic. This suggests that educators and teachers should spend more time understanding the theoretical and practical basis for learning and playing in a completely new educational setting. This also includes the psychological, emotional, and physical adjustments that COVID-19 demands of both teachers and students.

Concerning the modelled teachers’ perceptions and behavioural intentions, the findings revealed that students’ trust in their peers, instructional leadership and teachers’ self-efficacy perspectives positively enhance teachers’ intentions to implement PBL in schools significantly. Respectively, these findings have notable theoretical and practical implications in contemporary educational situations. The findings redirect understanding into accepting that promoting trust among students encourages mutual learning and information sharing among students, which eventually enhances teaching effectiveness. This also encourages information sharing and mutual learning among colleagues. Consequently, teachers are psychologically attracted and inspired to implement PBL methods and practices under such conditions. Hence, this demands a significant level of attention from teachers’ perspectives to be directed to students’ concerns when implementing PBL in schools. The findings practically encourage school administrators to boost teacher self-efficacy to increase kindergarten school teachers’ information searching and learning as well as the reinventing of instructional strategies to facilitate students’ learning. Additionally, the possibilities of developing teachers’ critical feedback and reflective practices on their teaching methods are conceivable.

In addition to extending, developing, and validating prior studies’ robustness in yielding precise, reliable, and valid ideas, this research contributes to the formulation of curriculum decision-making and educational policy. As a result, related studies [4,12,27,34,44] had not widened their scope to examine how the perspectives of students’ trust in peers and teachers’ self-efficacy have an interactive influence on teachers’ behavioural intentions to implement PBL. This study also provides some empirical substance to the discussion on the use and implications of PBL methods and practices within changes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic from teachers’ leaders, allower and afforder roles, to playful teaching practices. Considering changes in learning methods and practices triggered by the pandemic, kindergarten administrators should enhance PBL’s implementation in kindergarten schools. Practically, these implications were long overdue. As a result, the results provide dynamic contemporary insights and contributions to profit maximisation and corporate stakeholder theory development.

Lastly, inferences can be drawn from the face-to-face interview approach applied in this study that various forms of PBL confer distinct benefits. Therefore, we conclude this study by arguing that kindergarten teachers must categorise classroom-based approaches to PBL based on psychological frameworks, cognitive structures, or mental processes. These principles are novel to flexible knowledge, skills, and capabilities; and active and strategic metacognitive reasoning PBL principles established in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education [67].

Limitations and Future Research Directions

First, the study confines its examinations to kindergarten schools in Erbil, Kurdistan. As a result, the findings cannot be generalised to other school types, governorates, and countries. Such limitations should provoke future research on this subject to dispel the preoccupation that play-based learning methods and practices are exclusively applicable to kindergarten school contexts. A separate examination of public kindergarten teachers’ perspectives on PBL will be critical for this study because their views may differ from those of private kindergarten teachers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Q.O.; Methodology, K.Q.O.; Software, K.Q.O.; Validation, F.M.; Formal analysis, K.Q.O.; Resources, K.Q.O.; Data curation, K.Q.O. and F.M.; Writing—original draft, K.Q.O.; Writing—review & editing, F.M.; Supervision, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest were reported by the authors.

References

- Asiri, M.J. Do teachers’ attitudes, perception of usefulness, and perceived social influences predict their behavioral intentions to use gamification in EFL classrooms? Evidence from the Middle East. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2019, 7, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; San Juan, V. Play-based interview methods for exploring young children’s perspectives on inclusion. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2015, 28, 610–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyle, A.; Bigelow, A. Play in kindergarten: An interview and observational study in three Canadian classrooms. Early Child. Educ. J. 2015, 43, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Keung, C.P.C.; Tam, W.W.Y. What facilitates kindergarten teachers’ intentions to implement play-based learning? Early Child. Educ. J. 2022, 50, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.; Isa, F.M.; Mazhar, F.F. Online teaching practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Process Int. J. 2020, 9, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutarto, S.; Sari, D.P.; Fathurrochman, I. Teacher strategies in online learning to increase students’ interest in learning during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Konseling Dan Pendidik. 2020, 8, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarkar, P. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education system. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 3812–3814. [Google Scholar]

- Okojie, M.U.; Bastas, M.; Miralay, F. Using Curriculum Mapping as a Tool to Match Student Learning Outcomes and Social Studies Curricula. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 850264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyvönen, P.T. Play in the school context? The perspectives of Finnish teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2011, 36, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistillo, G. Pedagogy of care and community thinking for a new cognitive democracy: Theories of play and practices of power. Form. Insegn. 2022, 20, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yin, H.; Li, Z. Exploring the relationships among instructional leadership, professional learning communities and teacher self-efficacy in China. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2018, 47, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Zheng, X. Facilitating professional learning communities in China: Do leadership practices and faculty trust matter? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 76, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.Y.; Chiou, W.B. Achievement, attributions, self-efficacy, and goal setting by accounting undergraduates. Psychol. Rep. 2010, 6, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, S.; Bird, J. Observing and assessing young children’s digital play in the early years: Using the Digital Play Framework. J. Early Child. Res. 2017, 15, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickstrom, H.; Pyle, A.; DeLuca, C. Does theory translate into practice? An observational study of current mathematics pedagogies in play-based kindergarten. Early Child. Educ. J. 2019, 47, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy-Evans, O. Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. 2020. Available online: https://www.simplypsychology.org/Bronfenbrenner.html (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Tudge, J.; Rosa, E.M. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory. In The Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Development; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Li, H. Eduplay: Beliefs and practices related to play and learning in Chinese kindergartens. In Play and Learning in Early Childhood Settings; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbeck, M.; Yim, H.Y.; Lee, L.W. Play-based learning. In Teaching Early Years; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2020; pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S. New concepts of play and the problem of technology, digital media and popular-culture integration with play-based learning in early childhood education. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2016, 25, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyle, A.; DeLuca, C. Assessment in play-based kindergarten classrooms: An empirical study of teacher perspectives and practices. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 110, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.N. Investigating Teacher Perceptions of Montana Kindergarten to Second-Grade Play-Based Learning Practices during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Montana, Missoula, MT, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S. Play in the time of pandemic: Children’s agency and lost learning. Education 2022, 50, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadafora, N.; Reid-Westoby, C.; Pottruff, M.; Wang, J.; Janus, M. From full day learning to 30 minutes a day: A descriptive study of early learning during the first COVID-19 pandemic school shutdown in Ontario. Early Child. Educ. J. 2022, 51, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, B.; Eivers, A.; Walker, S. The state of play-based learning in Queensland schools. Australas. J. Early Child. 2023, 48, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W. Teacher efficacy: Capturing and elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2001, 17, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Lee, J.C.K.; Jin, Y. Teacher receptivity to curriculum reform and the need for trust: An exploratory study from Southewest China. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2011, 20, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead, P. Developing an understanding of young children’s learning through play: The place of observation, interaction and reflection. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2006, 32, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P. Observing, planning, guiding: How an intentional teacher meets standards through play. YC Young Child. 2018, 73, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.H.; Chen, H.H. What increases learning retention: Employing the prediction-observation-explanation learning strategy in digital game-based learning. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 31, 3898–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyles, J. Ebook: AZ of Play in Early Childhood; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pyle, A.; Danniels, E. A continuum of play-based learning: The role of the teacher in play-based pedagogy and the fear of hijacking play. Early Educ. Dev. 2017, 28, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bransford, J.; Brophy, S.; Williams, S. When computer technologies meet the learning sciences: Issues and opportunities. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 21, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyle, A.; Poliszczuk, D.; Danniels, E. The challenges of promoting literacy integration within a play-based learning kindergarten program: Teacher perspectives and implementation. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2018, 32, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubikava-Moan, J.; Hjetland, H.N.; Wollscheid, S. ECE teachers’ views on play-based learning: A systematic review. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 27, 776–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, S.; Rogers, Y. Let’s get physical: The learning benefits of interacting in digitally augmented physical spaces. Comput. Educ. 2004, 43, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M. More play, please: The perspective of kindergarten teachers on play in the classroom. Am. J. Play 2015, 7, 347–370. [Google Scholar]

- Van Maele, D.; Van Houtte, M.; Forsyth, P. troduction: Trust as a Matter of Equity and Excellence in Education. In Trust and School Life; Van Maele, D., Forsyth, P., Van Houtte, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vostal, M.; LaVenia, K.N.; Horner, C.G. Making the shift to a co-teaching model of instruction: Considering relational trust as a precursor to collaboration. J. Cases Educ. Leadersh. 2019, 1, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralay, F. Gaining of common culture perception to students in divided societies and the role of Art course in this context; Northern and Southern Cyprus. SHS Web Conf. 2018, 48, 01016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blase, J.; Blase, J. Principals’ instructional leadership and teacher development: Teachers’ perspectives. Educ. Adm. Q. 1999, 35, 349–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, K.S.; Dretzke, B.; Wahlstrom, K. How does leadership affect student achievement? Results from a national US survey. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2010, 21, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesseha, E.; Pyle, A. Conceptualising play-based learning from kindergarten teachers’ perspectives. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2016, 24, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashani, Z.G.; Yazdi, S.M.; Ghasemzadeh, S. The Effectiveness of the Designed Play-Based Educational Program on Phonological awareness in Children with Down syndrome. Middle East. J. Disabil. Stud. 2016, 1–11. Available online: https://www.sid.ir/paper/732837/en (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Lestari, P.A.S.; Gunawan, G. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on learning implementation of primary and secondary school levels. Indones. J. Elem. Child. Educ. 2020, 1, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zysberg, L.; Schwabsky, N. School climate, academic self-efficacy and student achievement. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 41, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, P. Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mulisa, F. When Does a Researcher Choose a Quantitative, Qualitative, or Mixed Research Approach? Interchange 2022, 53, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. Triangulation 2.0. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, E.J.; Delair, H.A. Patterns of resistance and support among play-based teachers in public schools. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2004, 5, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, W.; Gage, C.Q.; Tarter, C.J. School mindfulness and faculty trust: Necessary conditions for each other? Educ. Adm. Q. 2006, 42, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Structural equation modelling and regression analysis in tourism research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 777–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.; Schermelleh-Engel, K. Structural Equation Modeling: Advantages, Challenges, and Problems. In Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL; Goethe University: Frankfurt, Germany, 2009; pp. 1–4. Available online: http://kharazmi-statistics.ir/Uploads/Public/MY%20article/Structural%20Equation%20Modeling.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Lei, P.W.; Wu, Q. Introduction to structural equation modeling: Issues and practical considerations. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 2007, 26, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.; Da Silva, D.; Bido, D. Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Braz. J. Mark. 2015, 13, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bonett, D.G.; Wright, T.A. Cronbach’s alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurlo, M.C.; Della Volta, M.F.C.; Vallone, F. COVID-19 student stress questionnaire: Development and validation of a questionnaire to evaluate students’ stressors related to the coronavirus pandemic lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 576758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.M.S.W.; Shantel, D.; Penny, B.; Thomas, M.A.T. Teaching through collective trauma in the era of COVID-19: Trauma-informed practices for middle level learners. Middle Grades Rev. 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Bao, X.; Yan, J.; Miao, H.; Guo, C. Anxiety and depression in Chinese students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 697642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfud, I.; Gumantan, A. Survey of student anxiety levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pendidik. Jasm. Olahraga Dan Kesehat. 2020, 4, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Agosto, N.M.; Soto-Crespo, J.G.; Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer, M.; Vega-Molina, S.; García Coll, C. Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory revision: Moving culture from the macro into the micro. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 12, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukackė, V.; Guerra, A.O.P.d.C.; Ellinger, D.; Carlos, V.; Petronienė, S.; Gaižiūnienė, L.; Blanch, S.; Marbà-Tallada, A.; Brose, A. Towards Active Evidence-Based Learning in Engineering Education: A Systematic Literature Review of PBL, PjBL, and CBL. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R. Mindfulness and Academic Optimism: A Test of Their Relationship. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2011. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/5ff1aa0abc201fde424d9b84a8b4a6fe/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Smith, K.; Maynard, N.; Berry, A.; Stephenson, T.; Spiteri, T.; Corrigan, D.; Mansfield, J.; Ellerton, P.; Smith, T. Principles of Problem-Based Learning (PBL) in STEM Education: Using Expert Wisdom and Research to Frame Educational Practice. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]