Abstract

Since the 1990s, discussion on changes in the welfare state models and social policies shifts has intensified globally, primarily driven by the new technological revolution and aging populations. In parallel, Germany has placed increasing importance on preventive social policies, aligning with the evolving concept of social investment theory in Europe. This article examines preventive social policy in Germany through the analysis of policy documents, expert reports, and academic papers. We elucidate its conceptual framework, guiding principles, and action strategies. Furthermore, we showcase representative preventive social policies at both the federal and state levels, highlighting their accomplishments and challenges. Lastly, we endeavor to bridge the theoretical and practical aspects of German preventive social policy with China’s social policy reform goals. We suggest that China can draw lessons from Germany’s innovative concept of preventive social policy, emphasizing a life-cycle perspective in institutional design, policy implementation, and outcome evaluation, as well as fostering diverse networking approaches at the governance level to address the challenges inherent in social policy development.

1. Introduction

Since the 1990s, global discussions have intensified regarding changes in welfare state models and the transformation of social policies in response to the new technological revolution, population aging, and socioeconomic development. In 2003, China shifted its development model from a unilateral focus on GDP growth to a more balanced approach, emphasizing coordinated economic and social development. This shift prompted a significant emphasis on the country’s long-neglected welfare system. Historically, China’s social policy followed a residual welfare model [1], where the government played a limited role in welfare provision, intervening only when individuals, families, or communities failed to meet basic needs. This approach primarily targeted certain vulnerable groups and aimed to provide remedial assistance [2]. However, with changing family structures, increasing urbanization, industrialization, rising social risks, and globalization challenges, the residual welfare model can no longer adequately support sustainable social welfare development [3]. In response, the 6th Plenary Session of the 16th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) proposed “establishing a social security system covering urban and rural residents”. Subsequently, the 3rd Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee advocated “establishing a fairer and more sustainable social security system”. Recognizing China’s status as a developing country, a “moderately universal welfare model of social policy” was proposed, distinguishing it from the more comprehensive welfare systems found in developed countries. This model aimed for a “universal welfare model”, shifting the focus from the “limited welfare” of the residual model, which mainly targeted the elderly, children, the disabled, women, and the poor, to a “broad welfare” approach addressing multifaceted welfare needs for all community members [4]. However, the development of social policy in China continues to face several challenges. Firstly, the implementation of the “moderately universal welfare model” has resulted in a so-called “shortfall effect” in social welfare, particularly affecting disadvantaged groups like economically struggling elderly individuals, disabled individuals, and children in need. Government responses to these issues have largely taken the form of social assistance and emergency interventions [5]. Secondly, disparities in the distribution of welfare resources between urban and rural areas and among different regions in China have led to imbalances and inadequate development, posing a significant challenge to the goal of achieving “common prosperity” [6]. Lastly, as material living standards improve and society progresses, people’s demands for social justice and welfare services continue to grow [7].

While China and Germany have distinct historical backgrounds, differing political systems, social cultures, and economic structures, there are notable parallels in their social policy evolution. Both nations have transitioned from redistributive social policies to developmental ones, seeking to regulate the relationship between welfare subjects and establish a rational social welfare responsibility framework. Moreover, their social policy reforms share a common focus on enhancing the self-development capabilities and sustainable potential of disadvantaged groups [8]. In 1889, Germany became the world’s first country to implement a social insurance scheme for old-age pensioners [9]. Since then, Germany has effectively employed government macro-control to facilitate the advancement of social policies—a strategy somewhat akin to China’s approach. Consequently, Chinese scholars contend that Germany’s experiences in social policy can offer valuable lessons for China’s own social policy development [10,11,12]. Given China’s current objective of completing the building of a moderately prosperous society, it is becoming imperative to harness the regulatory power of social policies. This is especially crucial in addressing social inequalities stemming from initial income distribution disparities, enhancing the well-being of the disadvantaged, and ensuring their access to essential services [12]. According to the 7th China Population Census, 13.5% of China’s population was aged 65 and above in 2020. Projections suggest that China is expected to officially enter an aged society in 2022 [13]. European nations, including Germany, faced this demographic challenge as early as the 1970s. The coping strategies implemented by these European countries can serve as valuable lessons for China [14]. Consequently, Chinese scholars have undertaken comparative studies on elderly services [15], pension insurance [16], long-term care insurance [17], and other related aspects. By examining demographic trends, identifying commonalities, and understanding distinctions in the aging challenges faced by China and Germany, these studies aim to inform China’s approach to aging-related issues.

In Europe, the vision of a “social investment welfare state” by Anthony Giddens has exerted a profound influence on social policy reform [18,19]. Over the past two decades, there has been an increasing emphasis on the positive concept of “prevention” within the framework of social investment theory. This concept advocates addressing social problems at their earliest stages rather than merely compensating for them afterward. Not only does this approach align more closely with prevailing societal values, but it also yields substantial socioeconomic benefits [20]. In Germany, researchers have not only conducted extensive theoretical and empirical studies on preventive social policy but have also implemented robust policy initiatives at both the federal and state levels. However, limited attention has been given to the concept and practice of “preventive social policy” in Germany and its potential relevance to social policy reform in China. To bridge this gap, this article delves into the concept’s nuances, guiding principles, and action strategies in German preventive social policy. Furthermore, it explores how these principles might align with the enhancement of China’s “moderately universal welfare model of social policy” and contribute to the sustainable development of China’s social welfare system.

To conduct this research, we performed a comprehensive literature search using the German keyword “Vorbeugende/Präventive Sozialpolitik” (preventive social policy). A typical source of information is the book titled “Vorbeugende Sozialpolitik”, published by Klammer and Brettschneider in 2021. This book encapsulates research findings spanning the last two decades in the field of preventive social policy in Germany [21]. Additionally, we supplemented our analysis with policy documents, publications, evaluation reports, and news available on official websites of authorities responsible for specific preventive social policies. These sources collectively offer insights into the practices and outcomes of preventive social policy in various domains of action.

2. Social Investment Theory and European Social Policy Reform

In the late 1990s, as economic globalization continued to advance, the limitations of traditional welfare state models became increasingly evident. Anthony Giddens advocated for the concept of a “social investment state” as an alternative to the traditional welfare state. This new approach prioritized investments in human capital rather than direct economic assistance [18]. Over time, Giddens’ theory gained prominence and became the dominant paradigm for shaping social policy in Europe [22]. At its core, the social investment state represents a positive welfare model, emphasizing a positive relationship between social equity and economic benefits. It redefines social policy spending, viewing it as “productive” rather than “unproductive,” as it contributes to economic efficiency [23] (p. 261). Consequently, the concept of “social investment” reorients social policy and adjusts the allocation of resources based on the goal of “comprehensively and universally upgrading human capital” [23] (p. 264). This shift in focus moves away from merely maintaining living standards and toward securing lifelong human capital. The life-cycle perspective also transitions from primarily addressing retirement to a more early-stage approach, aimed at reducing pension expenditures and increasing investments in the future [24] (p. 114). Additionally, the approach evolves from passive fiscal transfers to active social services that incentivize individuals to participate in the labor market [23] (p. 260).

In the European Union (EU), the concept of a “social investment country” found expression in the expert paper on “future social policy and European social model” under the framework of the Lisbon Strategy [25]. Additionally, elements of the social investment approach are integrated into several principles of the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) [26] (p. 3). In 2001, during Belgium’s presidency of the Council of the European Union, a study titled “Why We Need a New Welfare State” was commissioned, advocating for a “child-centered social investment strategy” [19]. In the subsequent years, the social investment approach gained traction and became an integral part of numerous European expert papers and declarations. Following the adoption of a “Social Investment Convention” by the European Parliament in November 2012, the European Commission introduced the “Social Investment Package” in February 2013. This initiative urged EU Member States to increase their investments in preventive social welfare and social services across the life cycle. The focus was on enhancing people’s skills and qualifications, with particular attention to the stages of childhood and youth, as well as addressing child poverty.

In Germany, proponents of the social investment theory recognized the need for a fundamental shift in the focus of social policy activities. They emphasized the transition from a monetary redistribution policy to a social investment approach, wherein social policy increasingly relies on “tools to activate social human capital” [27] (p. 262). The overarching objective of the welfare state shifted from providing “aftercare” responses to life risks through monetary transfers like pensions, unemployment benefits, or sickness benefits, to proactively investing in areas that empower individuals to independently address social challenges. Research on preventive social policy in Germany has also advanced significantly. Scholars such as Kaufmann [28], Dingeldey [29], Schröder [30,31], Brettschneider [32], Allmendinger and Nikolai [33] and Jochem [34,35] have delved into the concepts and framework ideas underpinning preventive social policy. Busemeyer explored the implementation of social investment policies alongside compensatory social policies in OECD countries. By comparing public expenditures on social policies, he categorized countries into four groups, with Germany, as of 2010, being classified as a high-compensatory-spending and low-social-investment country [36]. Schröder et al. conducted a comparative study of social investment policies in the German federal states (Bundesländer) from 2003 to 2017. Their findings indicate that the often-discussed transformation from a conservative welfare state to a social investment state has influenced the practical and communicative dimensions of social policy at the state level. Government statements have increasingly adopted the paradigm of preventive social policy since the early 2000s [37]. Additionally, at the municipal level, Bothfeld and Steffen examined the implementation of a comprehensive social investment strategy in the city of Bremen, with a specific focus on early childhood education (U3 care). Their study revealed a deliberate effort to redefine childcare as “early childhood education” within Bremen’s framework. This shift extended professional quality standards to the early childhood sector and promoted greater educational continuity between different levels [38]. Collectively, these studies illustrate the practical application of the preventive social policy concept rooted in social investment theory. The primary objective is to complement traditional compensatory social policies with preventive models and methodologies, aiming to enhance societal well-being and resilience.

3. Evolution of German Social Policy

In the 1990s, as Germany grappled with the economic and social consequences of reunification, discussions and practical attempts at social policy reform gained momentum. The Kohl government initiated the first round of cuts to the German social security system during their last legislative period (1994–1998). Subsequently, under the leadership of the red–green coalition government led by Chancellor Schröder (1998–2005), Germany embarked on comprehensive structural reforms of the welfare state. These reforms aimed not only to reduce social security standards but also to explore concepts that could enhance the existing welfare structure. The term “social investment” emerged as a significant welfare state strategy during the Schröder era [39] (p. 58) and became a central theme in the Prime Minister’s Office document in December 2002. This period witnessed a shift in German social policy from a “caring welfare state” (fürsorgender Wohlfahrtstaat) to an “activating welfare state” (aktivierender Wohlfahrtsstaat) [40]. The intervention logic previously dominated by the “caring welfare state” was criticized for its emphasis on post-inequality and risk compensation rather than proactive risk avoidance. It was also faulted for relying primarily on passive monetary policies rather than “activating” policies, maintaining status differences instead of fostering equal opportunities, and prioritizing “current consumption” over “investing in the future”. As a result, a key objective of the welfare state reform known as “Agenda 2010” was to shift government spending from the “consumptive” realm to the “investment” sphere. This paradigm shift in social policy manifested in welfare cuts in the “consumptive” sphere and increased investments in civic engagement and personal responsibility [20] (p. 12). The activating welfare state no longer primarily aimed at compensating for life risks after they occurred but focused on “activating” individuals by equipping them to manage these risks proactively. During this period, a form of “zero-sum logic” emerged in the social policy reform debate. There was competition for financing between traditional “consumptive” government expenditures and the “investment” government expenditures advocated by the activating welfare state. “Consumptive” social expenditures like pensions, unemployment benefits, and social assistance were perceived in opposition to “investment” social expenditures such as education [20] (p. 10). This marked a fundamental shift in how government resources were allocated in pursuit of social policy objectives.

From the European financial and economic crisis in 2008–2009 to the COVID-19 crisis in 2020, Germany witnessed significant improvements in its economic and fiscal situation. Unemployment rates steadily declined, the number of individuals contributing to social insurance increased, and the government’s budgetary position improved considerably. Consequently, the conceptual opposition known as “zero-sum logic” gradually weakened [20] (p. 16). Demands for substantial cuts in the social sector also diminished, and instead, a series of social policy reforms were implemented between 2010 and 2020. These included the Pension Insurance Benefits Improvement Act (RV-Leistungsverbesserungsgesetz) of 2014, the three Care Strengthening Acts (Pflegestärkungsgesetze I, II, III) enacted between 2014 and 2016, the Federal Participation Act (Bundesteilhabegesetz) of 2016, and the Minimum Hourly Wage Act (Mindestlohngesetz) of 2015. During this period, the concept of the “activating welfare state”, which had been employed since 1998, gradually gave way to the “preventive welfare state” (vorsorgender Sozialstaat) [35,41]. The discourse surrounding the “Agenda 2010”, with its focus on activating the labor force and increasing individual responsibility, was superseded by an emphasis on social participation, with its focus on the concepts of fiscal consolidation and stimulating growth through investments in human capital. Both concepts evolved within the framework of the social investment theory, but they diverged in their approaches. “Activating social policy” primarily aimed at reinforcing individual responsibility through mechanisms like sanctions [42]. In contrast, “preventive social policy” concentrated on activating individual responsibility by establishing conditions for self-determination through individual empowerment and structural improvements. The emphasis was on strengthening budgets and promoting growth through investments in human capital [20]. In Germany, preventive social policy is not just a theoretical concept; it has translated into practical action. A wealth of experience has been accumulated at the state level, particularly in the domains of children, youth, family, and social policy, reflecting the country’s commitment to fostering social participation and enhancing the well-being of its citizens.

4. What Is Preventive Social Policy in Germany

As per government statements, expert reports, and academic research [31,43,44,45], the development of “preventive social policy” discussed in this paper is rooted in a proactive approach. Its central guiding principle is to promote self-awareness and equal opportunities for all members of society. This principle aligns with a life cycle-oriented perspective and emphasizes networking as the specific action strategy. In essence, preventive social policy aims to empower individuals across their entire life journey, fostering a sense of agency and ensuring equitable access to opportunities and resources throughout society. Networking is instrumental in creating a supportive ecosystem that facilitates these objectives and enables collective efforts towards social development and well-being.

4.1. Based on a Comprehensive Concept of “Prevention”

The concept of “prevention” traditionally encompasses interventions designed to prevent, delay, or mitigate the negative consequences of socially undesirable events, conditions, developments, or behaviors. However, there has been criticism within the academic community regarding this narrow understanding of prevention. Critics argue that this traditional view is “is one-sidedly normative, deficit-oriented, and emphasizes a high degree of regulation” that “leads to gradual disempowerment as well as the generalization of mistrust” [43]. In response to these criticisms, preventive social policy advocates for a more comprehensive concept of “prevention” that places a greater emphasis on positive objectives. The German Working Group for Child and Youth Welfare (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kinder- und Jugendhilfe) articulated this broader concept of “prevention” in a discussion paper on strengthening preventive work in child and youth welfare. They emphasized that “prevention” should not solely aim to prevent or circumvent problematic developmental processes but should also actively promote positive conditions for growth across all areas of child and youth welfare [46] (p. 2). German sociologist Albert Scherr further elaborates on this proactive concept of “prevention”. It shifts the focus towards the promotion and empowerment of self-determined lifestyles and equal participation. In doing so, it expands and complements the traditional understanding of “prevention” [47]. Therefore, within the framework of preventive social policy, the notions of “promotion and empowerment” (Fördern und Befähigen) constitute two fundamental aspects, underscoring the importance of fostering positive conditions for individuals to thrive and enabling them to actively participate in society.

4.2. Self-Determination and Equality of Opportunity as Guiding Principles

“Promotion and empowerment” in the context of preventive social policy means ensuring that individuals have the capability to lead self-determined lives and have equal opportunities for participation in society. The realization, protection, and promotion of individual self-determination are key objectives of the German Basic Law (Grundgesetz) and the German welfare state. “Self-determination” is one of the guiding principles of preventive social policy, signifying that the welfare state can provide institutional guarantees and social policy support to enable individuals to pursue their life plans as they wish. This concept is closely linked to the notion of equal opportunities, as outlined in the guidelines on social security in Volume I of the German Social Code I (Sozialgesetzbuch I), which states that equal conditions should be established to facilitate the free development of personality, particularly among young people. Therefore, the creation of as many equal opportunities as possible is a fundamental prerequisite for promoting self-determination.

Preventive social policy in Germany seeks to “create structural and adaptive opportunities and conditions for all members of society to enable self-determined life plans to be realized” [48]. Self-determination and equal opportunities are not just policy goals but also guiding principles for social interventions by the welfare state:

Equal Access: To ensure equal access to services and measures, the welfare state should minimize barriers, avoid discrimination and stigmatization, adopt a demand- and resource-oriented approach, and be culturally and difference-sensitive.

Safeguarding Subjectivity: It is crucial to safeguard the subjectivity and self-determination of service recipients. This includes the right to access information, choose facilities and service providers, participate in social assistance, and have an active voice in shaping measures.

Collective Participation: Opportunities for collective participation and co-determination should be maximized in the establishment of welfare state institutions and procedures [20] (pp. 36–37).

A policy focused on expanding self-determination and equal opportunities for all members of society is also a policy against social deprivation, segregation, and the intergenerational transmission of disadvantages. This approach is particularly relevant in family policy, education policy, and labor market policy, where ensuring equal opportunities for social participation and self-fulfillment is essential for all members of society.

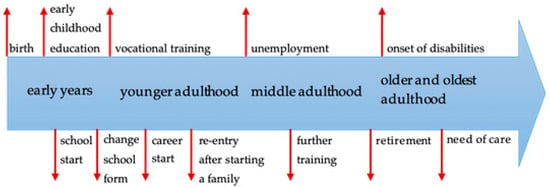

4.3. Life-Cycle-Oriented Social Policy

Preventive social policy recognizes that success and risk factors vary across different stages of a person’s life, including early years, young adulthood, middle adulthood, older adulthood and oldest adulthood (Figure 1, blue arrow). Moreover, earlier life stages profoundly influence the opportunities and challenges individuals face in later stages of life. As a result, preventive social policy is oriented towards addressing these various life stages [20,49]. In this sense, preventive social policy pursues a long-term orientated approach to prevention that focuses on the whole life course [36]. Furthermore, transitions between different stages of an individual’s life cycle are the most sensitive for social policy; policymakers, therefore, must pay special attention to the key decisions made at transitions (school start, career start, re-entry after starting a family, and retirement, etc.) (Figure 1, below arrow) in the individual life stages for successful participation, especially in the education and employment system and in social life. Finally, there are proved successes and risk factors that have a particular impact on these transitions and have a considerable (positive or negative) influence on subsequent life stages (Figure 1, above arrow) [20,50]. In essence, preventive social policy recognizes that a person’s life is a dynamic journey with multiple stages, each requiring specific support and opportunities to promote well-being and equal participation. Policymakers must be attuned to the unique challenges and opportunities associated with each life stage to ensure the effectiveness of preventive measures.

Figure 1.

Critical life stages (blue arrow), between life stages (below arrow), and proved successes and risks (above arrow). Source: Adapted from Ref. [50] (p. 4).

Preventive social policy is grounded in a comprehensive understanding of “prevention”. Within this framework, the life-cycle perspective serves two complementary functions: risk elimination and social molding [51] (pp. 55–56); [52] (pp. 450–451).

Risk Elimination: Preventive social policy emphasizes the importance of addressing social risks not only in the current life stage but also in a forward-looking manner to avoid or minimize adverse social consequences in subsequent life stages. This proactive approach involves identifying risks in advance and intervening early to prevent them from leading to long-term effects. Such an approach aligns with the guiding principle of equal opportunities, as it recognizes that providing interventions and support at an early stage of childhood can help level the playing field and promote equitable development.

Social Molding: Transitions between life-cycle stages are often pivotal moments in individuals’ lives and can have enduring, long-term impacts. Preventive social policy acknowledges that individuals and society together play roles in shaping these transitions. It aims to create conditions that empower individuals to shape their own life cycles and participate in shaping society collectively. This aligns with the guiding principle of self-determination, as it involves establishing an institutional framework that enables self-determined life plans.

The two functions mentioned above can be summarized as “ensuring diverse options and building safe transitions” [53].

4.4. Networking Approaches

The effective response to social problems often requires coordinated action by multiple stakeholders within an integrated framework. This integrated approach is crucial in areas like education policy, where various policy domains, including education, the labor market, and the welfare state, intersect within socially organized networks. These networks bring together different actors who pool their resources and collaborate in complementary ways to expand the range of services and avoid duplication of efforts [54] (p. 8). In this process, structures characterized by “spatially adapted and content-justified pathways” naturally evolve to provide support to specific target groups. The networking approach brings forth an inherent “added value” or a “positive reinforcement” for the involved actors [55] (p. 470). Consequently, the governance of preventive social policies should be rooted in a socio-spatial orientation strategy. Socio-spatial orientation embodies a comprehensive perspective in social work, one that transcends an individual-centered focus. It is a concept of reflection and action aimed at developing humane and socially just living conditions [56] (pp. 26–28). Social policy measures guided by socio-spatial orientation necessitate the integration of various existing social services and strategies designed to shape and transform the social landscape, rather than merely focusing on individual transformation. Approaches such as the “Early Help” (Frühe Hilfe) networks, local prevention chains, and regional prevention landscapes in Germany all strive to establish a comprehensive network of support, guidance, and maintenance. By orchestrating the actions of all pertinent stakeholders within the social context, these approaches foster deep cooperation while minimizing barriers to accessing assistance and eradicating discrimination. For instance, the prevention chain model is designed to establish an extensive and sustainable network encompassing children, adolescents, and parents within a community, involving the active participation of all stakeholders. The objective is not to create a new, additional network but rather to consolidate existing networks, services, and participants to collaborate synergistically within the framework of an all-encompassing municipal strategy. When necessary, new services can be developed collaboratively, moving away from the mere coexistence of existing networks and activities towards genuine cooperation [57]. This form of networking is locally organized in a “bottom-up” manner, not only enhancing social participation but also nurturing a strong sense of identification with social work among participants.

5. Representative Preventive Social Policy Practices

In this section, we will delve into representative preventive social policy initiatives and measures in Germany, framed within a life-stage perspective.

5.1. Early Years: “Early Help” for Children and Adolescents

The early years hold exceptional significance in the development of children and adolescents. The concept of “Early Help” has been devised to detect family stress and potential risks to children’s well-being as early as possible. It places special emphasis on providing tailored, necessity-driven assistance to parents from the outset of pregnancy and throughout the early years of a child, up to the age of three. With the launch and implementation of the federal Early Help Initiative, Germany has established local and regional support systems [58]. At the state level, for instance, in North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), Early Help forms the foundation of support for families with children as part of the local prevention chain. Table 1 outlines the pertinent policies and measures.

Table 1.

Early years: timeline of critical steps taken at the federal and state levels for selected preventive social policies.

It should be noted that there are not comprehensive evaluations and data available for all the programs, primarily because these are long-term initiatives whose success cannot be gauged in the short term. Consequently, only selective results can be provided.

Data from the 2020 local authority survey conducted by the NZFH reveal variations among the networks across Germany, encompassing differences in staffing, network design, and the engagement of professionals from various domains [60]. Furthermore, the results of the survey highlight significant improvements in areas that are central to Early Help’s objectives. Particularly noteworthy is the enhancement in the capacity to support families in stressful situations with children up to the age of three, with 96.2% of municipalities reporting improvement (compared to 93.5% in 2015). Only 3.6% of municipalities observed no change, while a mere 0.2% noted a slight decline [60] (p. 11). Moreover, a majority of municipalities demonstrated an improved ability to detect early-stage risk situations in child development (2017: 92.2%; 2015: 91.4%) and to engage in collaborative efforts concerning children’s welfare in risky situations (2017: 88.9%; 2015: 89.1%) [60] (p. 11).

Nevertheless, the most prominent challenge in the ongoing conceptual evolution of Early Help, as perceived by municipal stakeholders, is the integration of the healthcare system. In 2017, 83% of municipalities were actively pursuing this objective, yet only 5% reported successful implementation, and 7.3% had not even considered it as a developmental goal. This underscores the formidable obstacles associated with inter-system cooperation, emphasizing the need for involvement from relevant ministries at both the state and federal levels, as well as corporate entities within the healthcare sector, such as medical associations, primary care physicians’ associations, and health insurance funds [60] (p. 11).

5.2. Younger Adulthood: Supporting the Transition from School to Work

The transition from school to work poses challenges for young people in light of evolving social and economic dynamics and the increasing demands of the labor market on their competencies and skills [61] (p. 36). In Germany, only a portion of students manage to smoothly transition from school to vocational training. In 2008, there were 70,000 pupils in Germany who left school prematurely without obtaining a diploma [62]. To address this issue, the Federal Government and the Länder expressed their commitment to reducing this number during the Education Summit in Dresden in October 2008, resulting in the creation of the “Education Chains Initiative” [63]. The Dresden Declaration, issued during the same summit on 22 October 2008, outlined the objective of reducing the percentage of school dropouts without qualifications from an average of 8 to 4% by 2015. Furthermore, it aimed to halve the number of young adults lacking vocational qualifications but capable of undergoing training, reducing it from 17 to 8% by 2015 [64]. In order to facilitate young individuals’ vocational orientation, establish a structured transition from school to work, and supply the labor market with skilled professionals, Germany has implemented a range of significant policies and measures (Table 2).

Table 2.

Younger adulthood: Timeline of critical steps taken at the federal and state levels for selected preventive social policies.

In 2015, approximately 47,500 young people across the country left school without a diploma, accounting for 6% of all school leavers, which was down from 8% in 2008, but not at the desired goal level of 4% [66]. The percentage of young adults aged 20–34 without vocational training decreased from a peak of 17.4% in 2006 to 13.4% in 2015; the goal was 8% [67]. While the targets outlined in the Dresden Declaration were not fully achieved, both indicators showed a declining trend. These trends are influenced by various factors, including geographical disparities, gender, and migrant backgrounds.

Despite clear goals, the Länder have not developed comprehensive, integrated and differentiated strategies and concepts for the younger-adulthood transition. In some Länder, it is explicitly integrated into the overall strategy, while in most Länder, it is treated as a separate area of action, often in the form of pilot projects. The degree of autonomy for regional action varies accordingly, ranging from providing guidelines and specific measures to setting quality standards and organizational framework guidelines, as well as implementing pilot projects in various regions or specific locations [65] (p. 28). It is justifiable for the Länder to tailor their strategy development according to their own evaluations and input from regional authorities. Throughout the strategy development process, it is crucial to create avenues for adolescents to participate and voice their individual needs. Offering personalized guidance to adolescents is essential, not only during vocational training but also during the transitional phase within the educational system [65] (p. 37).

5.3. Middle Adulthood: Creating a Family-Friendly Social Environment for People in Working Life

The phase of work and the associated transitions are pivotal junctures in an individual’s life, carrying profound implications for one’s social standing and developmental prospects. A fundamental goal of preventive social policy is to establish structural and environmental conditions that empower individuals to pursue self-determined, fulfilling, and personally successful career paths [48] (p. 1396). This, in turn, reduces the need for “aftercare” measures. In the context of the traditional family structure, the well-being and opportunities for development of each family member, including children, adolescents, and the elderly, are closely intertwined with the principles of equal opportunity and societal inclusion. Consequently, a central focus of contemporary family policy in Germany is to cultivate a family-friendly living and working milieu while advocating for a more equitable distribution of labor and family responsibilities. Achieving parity in these responsibilities largely hinges on enabling both parents to tailor their work hours to suit their individual needs. Table 3 presents the timeline of policy changes.

Table 3.

Middle adulthood: timeline of critical steps taken at the federal and state levels for selected preventive social policies.

As per the findings from the Enterprise Monitor Report on “Family-friendliness” published by the German Institute for Economic Research (Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft), several areas within businesses have witnessed an increase in the adoption of family-friendly measures when compared to the previous survey conducted in 2015. These areas encompass flexible working hours and work organization, parental leave and parental support, childcare provisions, services for caring for close relatives at home, and family service/information and counseling [69] (pp. 22–27). Notably, the report brings to light that the prevalence of a distinctly family-friendly corporate culture has grown since 2015, both from the standpoint of companies (2015, 41.2%; 2018, 45.9%) and that of employees (2015, 36.1%; 2018, 39.4%). However, a noticeable gap still exists between the family-friendliness envisioned by companies and what employees actually experience [69] (p. 12). Another positive trend is the heightened awareness within companies about the work–life balance of fathers. In 2015, approximately 35% of companies offered at least one measure to support fathers. By 2018, this figure had risen to around 53% [69] (p. 20).

Human resource managers are increasingly acknowledging the significance of fostering a family-friendly work environment, even for employees with no (current) caring obligations. Nonetheless, managing the integration of employees who utilize family-friendly measures with those who do not have caregiving obligations can introduce potential conflicts [69] (p. 6). Therefore, it is of the utmost importance for executives to strive for a fair balance of interests within their teams. This involves sensitizing both executives and employees to the understanding that demands and opportunities vary across different life phases.

5.4. Older and Oldest Adulthood: Assistance for Long-Term Care Demanders and Providers at the Earliest Opportunity

When examining the three resource levels of preventive care policy—family caregivers, professional outpatient care structures, and alternative resources for care provision, such as the potential of civil society within the social space—it becomes evident that family caregivers have consistently been the cornerstone of care services. Moreover, their significance is poised to grow even more critical in light of the anticipated shortage of professional caregivers [70]. Today’s family caregivers are evolving into the future demanders within aging care and long-term care systems. Consequently, providing support for family caregivers, as part of socio-political prevention, stands as a central tenet of preventive care policy. The objective here is twofold: firstly, to stabilize the well-being of individuals requiring care through preventative measures, thereby averting premature institutionalization, and secondly, to establish a sustainable approach in supporting private caregivers, often family members. Table 4 presents the timeline of significant policies.

Table 4.

Older and oldest adulthood: Timeline of critical steps taken at the federal and state levels for selected preventive social policies.

According to an assessment of long-term care released by the Institut für Sozialforschung und Sozialwirtschaft (iso) in 2019, the reform has resulted in a significant rise in the number of recipients under long-term care insurance, with a particularly noticeable impact in the field of outpatient care. The expansion of beneficiaries has been particularly notable in the outpatient care sector. The PSG II alone led to an increase of around 300,000 beneficiaries in 2017 and more than 500,000 by the end of 2018 [71] (p. 5). Additionally, there has been a positive trend in the utilization of long-term care counseling services. In 2018, 51% of those entitled to such services made use of them, a significant increase compared to the period when the Act on the Further Development of Long-Term Care was first introduced in 2009. The satisfaction with care counseling is noteworthy, with more than half (56%) of those in need of care reporting an improvement in their care situation as a result of counseling. Furthermore, the expansion of long-term care insurance benefits has contributed to a reduction in the number of recipients of long-term care assistance (Hilfe zur Pflege). With the PSG II, III coming into effect, there has been a significant decline in the number of recipients of long-term care assistance. In fact, the proportion of recipients of long-term care assistance among all individuals in need of long-term care decreased by 3% in 2017 compared to the previous year, reaching the lowest level since the introduction of long-term care insurance [71] (p. 7).

However, despite efforts to improve the framework conditions for higher staffing ratios in care facilities, recruiting additional staff for nursing work remains a significant challenge. The shortage of skilled personnel remains the most critical obstacle in this field [71] (p. 8). The demand for personnel in nursing professions cannot be met by local staff or skilled workers from EU countries. This shortage is further exacerbated by job vacancies in elderly care, which often remain unfilled for extended periods, averaging over 200 days. This trend of understaffing continues to rise [72]. Addressing the shortage of skilled workers in the care sector necessitates exploring various avenues, including attracting trainees from third countries, activating domestic potential, and attracting already-qualified care workers through recognition procedures. For example, the BMWi model project in Vietnam is one such initiative aimed at countering the shortage of skilled workers in care [73].

6. Discussion: German Lessons for China

While China and Germany may have different demographic situations, they both face the common trend of an aging population. Germany has experienced the challenges of an aging society earlier than China. Table 5 shows a comparison of selected population data for both countries.

Table 5.

Selected demographic data—China and Germany compared. Source from Refs. [74,75].

Germany’s approach to preventive social policy, rooted in the social investment theory, offers valuable lessons for the development of social policy in China.

Firstly, the foundational principles of Germany’s preventive social policy are highly compatible with the current objectives of China’s social policy. This alignment is particularly relevant in light of China’s dual emphasis on both social and economic policies. Central to this convergence is the shared commitment to enhancing individual self-determination and fostering autonomous development. Moreover, there is a strong focus on investing in human capital as a means of facilitating the broadest possible equality of opportunity. As China strives to establish a “moderately universal welfare model of social policy”, it is imperative to extend attention beyond the traditional beneficiaries of social support. While migrant workers, individuals with disabilities, the elderly with special needs, and women and children facing abandonment remain important focal points, it is equally crucial to direct efforts towards more discreet and frequently overlooked segments of the population. These often-overlooked groups encompass children who confront limited development opportunities due to their family backgrounds, recent graduates grappling with labor market integration following the attainment of diplomas, mothers encountering challenges in returning to the workforce after childbirth, and family caregivers who shoulder the responsibilities of nursing and caregiving. Recognizing and addressing the distinctive challenges faced by these groups is paramount for the comprehensive success of China’s evolving social policy. Furthermore, China should promote collective participation and co-determination as essential components of its social policy framework. By fostering platforms and opportunities for individuals and communities to actively engage in shaping their own destinies and influencing the policies that affect them, China can facilitate a transition from passive recipients of social support to empowered and engaged participants.

Secondly, adopting an institutional framework that considers the entire life cycle, formulating comprehensive measures, and evaluating the outcomes of preventive social policies can serve as a valuable strategy to address welfare polarization between urban and rural areas and regions in China. Currently, China’s welfare standards exhibit disparities across urban and rural areas, regions, occupations, social classes, and industries. The degree of system coordination and program consistency also fluctuates from county (city) to province (municipality directly under the central government) to nationwide, resulting in a fragmented social policy landscape that does not adequately promote the full and unhindered development of all individuals. The adoption of a life-cycle-oriented social policy framework would facilitate the elimination of disparities stemming from “place of origin”, “social status”, and “occupation”. Instead, it would place the focus squarely on the individual, with the human life cycle as the foundational principle. Germany’s ongoing efforts to extend the principles learned from childhood and adolescence to other transitional phases and provide lifelong support for individuals of all ages are particularly relevant for China. Individuals navigating similar transitional stages often encounter higher risks, necessitating targeted social policy measures to safeguard their well-being.

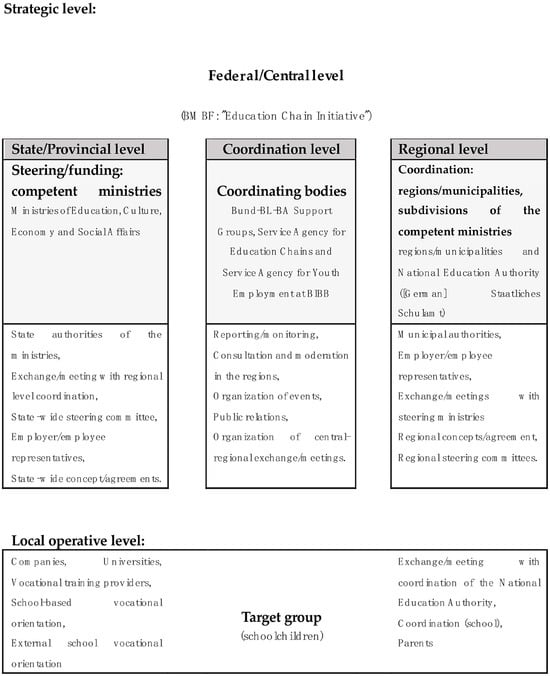

Thirdly, the networking strategy is conducive to promoting the coherence of social policies at the governance level. Social policy has fragmented into a variety of highly specialized policy areas, such as health, pensions, child and youth welfare, etc., with different traditions, organizational logics, combinations of actors and financing structures; horizontally and vertically, there are differences in the competences and financial capacities of local governments at different levels and geographies; in addition to government actors, there are different roles and capacities of multiple welfare actors, including public agencies, independent welfare organizations, private providers and civil society organizations. Effective interface management, therefore, relies on a networking strategy of cooperation. Different networking strategies are used in Germany in social policy-related programs and projects: for example, the prevention chain emphasizes the importance of shaping transitions between life stages from a life-cycle perspective; the prevention landscape focuses on social space; and local communities of responsibility emphasize the co-responsibility and ethics of the network. The governance of social policy in Germany presents a mixture of hierarchical governance, contract management, and networking strategies, which are interlinked. The introduction of networking strategies in China’s social policy work does not mean replacing other, existing governance models, but rather playing a complementary role. On the one hand, it is important to encourage greater involvement of civil-society actors, commercial and non-commercial service providers, and local stakeholders, in addition to state actors; on the other hand, increasing the importance of participatory and interactive, non-hierarchical forms of negotiation and cooperation based on voluntariness, trust and common goals in the networking process is conducive to a sustainable culture of cooperation. A network becomes a “success” when “both the strategic and the operational networks are in close exchange [with each other]” and close cooperation is established [74] (p. 42). Figure 2 shows how actors at different levels with different functions interact and co-operate with each other in a successful network, and is illustrated by the example of the German “Education Chain Initiative”.

Figure 2.

Networking of actors at different levels and with different functions.

To address the challenges of imbalanced urban–rural development and income inequality in China, it is essential to proactively engage all stakeholders within the social policy system. The preventive social policy’s socio-spatial-oriented network approach can serve as a crucial solution. On one hand, the networking approach’s primary objective is to foster active participation among all stakeholders in the network, facilitating information exchange and fostering cooperation to collectively shape social policies. On the other hand, this networking approach highlights the pivotal role played by municipal actors and encourages a socio-spatial perspective when formulating social policy strategies. For instance, in their pursuit of “achieving robust and sustainable development within the region”, the NRW state government places special emphasis on regions that are structurally weak and socially disadvantaged. They channel additional investments into these underprivileged areas through initiatives such as the European Structural Funds and collaborative projects. This strategy ensures that a person’s place of residence does not hinder their economic, social, or political participation, thereby reducing existing disparities and polarization between towns, villages, and neighborhoods [75,76].

Other challenges remain. Considerable disparities exist between China and Germany concerning their economies, political systems, cultures, and demographic structures. Consequently, caution is necessary when attempting to apply the German experience to the Chinese context. Notably, the vast difference in population size between China and Germany amplifies the complexity of formulating and executing preventive social policies in China. While Germany encourages population mobility between EU member states and migration from outside the EU to address caregiver shortages, China is not a country with a history of significant migration, rendering such measures less suitable. In addition, as preventive social policies are long-term strategies oriented towards the future, Germany has not yet developed comprehensive and reliable indicators or data for assessing the long-term “impact” of these social policy solutions. Existing studies often focus on individual programs, employing varying timeframes and research methodologies, which poses challenges in terms of measurement and comparability.

Due to space limitations in this study, only selected policies related to critical life stages have been presented. However, it is worth noting that numerous preventive social policies and measures have been explored in the German federal states (Länder) and municipalities. Future research could expand and deepen the examination of the design, implementation, evaluation, and adaptation of policies and measures pertaining to specific life stages.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, X.N.; writing—review and editing, U.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Duisburg-Essen and by Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (grant number 1225173-CHN-BUKA-CHN).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their suggested revisions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, S. Building an appropriate universal-type social welfare system in China. J. Peking Univ. (Hum. Soc. Sci.) 2009, 3, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T. Theory and reflection on social policy. Sociol. Stud. 2000, 4, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Sun, Q. Entering the Era of General Welfare: The Rational Choice of Chinese Social Policy. J. Nanchang Hangkong Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2009, 11, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.C. Social Welfare Service Reform and Development Strategies in China: From Protection of the Weak to Universal Protection of All Citizens. J. Renmin Univ. China 2011, 25, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.G. Structual Transformation of Social Policy System in China and Its Implementation Path. J. Nanjing Univ. (Philos. Hum. Soc. Sci.) 2021, 5, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, J.; Fang, K. Welfare Proximity, Territorial Justice and the Balanced Development of Social Welfare in China. Explor. Free Views 2020, 6, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Yue, J. The Evolution. Achievements and Challenges of China’s Social Policy in the Past 70 Years. J. Soc. Work 2019, 5, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C. Social Policy Paradigm Shift and Its Implications for the Improvement of China’s Social Policy. Soc. Constr. 2019, 6, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, M. Retirement and the moral economy: An historical interpretation of the German case. J. Aging Stud. 1987, 1, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pupu, G. The Enlightenments of German Social Security System to China: From the View of Social Policy. J. Yibin Univ. 2009, 9, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. Analysis of the State Model and its Influence on Social Policy and Social Work:China, Germany and the United States of America as Example. J. Soc. Work 2016, 3, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T. The Development of German Social Policy and Its Inspiration for China’s Shared Development. J. Shandong Youth Univ. Political Sci. 2017, 185, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Development Research Foundation (CDRF). China Development Report 2020: Trends and Policies on Population Ageing in China; China Development Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Du, P.; Wei, Y. European Countries’ Policy Responses for An Aging Society and Its Inspiration: Take France, Germany, and United Kingdom as Examples. Soc. Sci. Int. 2022, 9, 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. The historical analysis and experience research of German pension service system. Soc. Welf. 2020, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C. The main system of statutory pension insurance in Germany and its inspiration. Deutschland-Studien 2023, 38, 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F. The Institutional Origin, Dynamic Mechanism, and Enlightenment of German Social Long-term Care Insurance. Soc. Constr. 2022, 9, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, G. A child-centred social investment strategy. In Why We Need a New Welfare State; Esping-Andersen, G., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 26–68. [Google Scholar]

- Brettschneider, A.; Klammer, U. Vorbeugende Sozialpolitik: Grundlinien eines sozialpolitischen Forschungsprogramms. In Vorbeugende Sozialpolitik: Ergebnisse und Impulse; Klammer, U., Brettschneider, A., Eds.; Wochenschau Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2019; pp. 12–100. [Google Scholar]

- Klammer, U.; Brettschneider, A. (Eds.) Vorbeugende Sozialpolitik: Ergebnisse und Impulse; Wochenschau Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cantillon, B.; Van Lancker, W. Three Shortcomings of the Social Investment Perspective. Soc. Policy Soc. 2013, 12, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. Positive-Sum Solutions in a World of Trade-Offs? In Welfare States in Transition: National Adaptations in Global Economies; Esping-Andersen, G., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 1996; pp. 256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Palier, B. The re-orientation of Europe social policies towards social investment. Int. J. Polit. Cult. Soc. 2006, 1, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera, M.; Rhodes, M. Building a sustainable welfare state. West Eur. Polit. 2000, 23, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, S.; Alcidi, C.; Corti, F.; Salvo, M.D. Changing Social Investment Strategies in the EU. JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology; Joint Research Centre (JRC): Bruxelles, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Heinze, R.G. Vom Statuskonservierenden Zum Sozialinvestiven Sozialstaat; SSG Sozialwissenschaften: Köln, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, F.-X. Schutz–Sicherung–Befähigung: Dauer und Wandel im Sozialstaatsverständnis. Z Sozialreform. 2009, 55, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingeldey, I. Der aktivierende Wohlfahrtsstaat: Governance der Arbeitsmarktpolitik in Dänemark, Großbritannien und Deutschland; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2011; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, W. Vorsorge und Inklusion: Wie Finden Sozialpolitik und Gesellschaft Zusammen? Vorwärts-Buch Verlagsgesellschaft: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, W. Vorbeugende Sozialpolitik Weiter Entwickeln; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2014; Available online: http://www.fes.de/de/index.php?eID=dumpFile&t=f&f=2028&token=44125d11013fa835e5b8680156f5fd9edbef48f3 (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Brettschneider, A. On the way to social investment? The normative recalibration of the German welfare state. GPS 2008, 4, 19–66. [Google Scholar]

- Allmendinger, J.; Nikolai, R. Bildungs-und Sozialpolitik: Die zwei Seiten des Sozialstaats im internationalen Vergleich. SozW 2010, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochem, S. Skandinavische Arbeits-und Sozialpolitik: Vorbilder für den Vorsorgenden Sozialstaat; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jochem, S. Der “Vorsorgende Sozialstaat“ in der Praxis: Beispiele aus der Arbeits-und Sozialpolitik der Skandinavischen Länder; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2012; Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/ipa/09095.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Busemeyer, M.R.; Garritzmann, J.L. Bildungspolitik und der Sozialinvestitionsstaat. In Handbuch Sozialpolitik; Obinger, H., Schmidt, M.G., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 783–805. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, W.; Klenk, T.; Berzel, A.; Stöber, M.; Akel, A. Vorbeugende Sozialpolitik als Antwort auf soziale Ungleichheiten und Neue Soziale Risiken: Kommunikation und Steuerung Vorbeugender Sozialpolitik in den Bundesländern; Wochenschau Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2018; pp. 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bothfeld, S.; Steffen, M. Langsam aber sicher: Der Ausbau der Kinderbetreuung in Bremen als Beispiel für eine umfassende Sozialinvestitionsstrategie. Sozialer Fortschr. 2018, 67, 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, A. Wohlfahrtsstaatlichkeit in Deutschland: Tradition und Wandel der Zusammenarbeit mit zivilgesellschaftlichen Organisationen. In Zivilgesellschaft und Wohlfahrtsstaat im Wandel: Akteure, Strategien und Politikfelder; Matthias Freise, A.Z., Ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dingeldey, I. Aktivierender Wohlfahrtsstaat und sozialpolitische Steuerung. APuZ 2006, 50, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Heil, H. Der vorsorgende Sozialstaat. Berl. Repub. 2006, 4, 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, C.G. Aktivierende Sozialpolitik und individuelle Autonomie. Soziale Welt 2004, 55, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollinger, B. Prävention. Unintendierte Nebenfolgen guter Absichten. In Aktivierende Sozialpädagogik: Ein kritisches Glossar; Dollinger, B., Raithel, J., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2006; pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, H. Kein Kind zurücklassen! Vorbeugende Politik in Nordrhein-Westfalen. In Wirkungsorientierte Steuerung. Haushaltskonsolidierung Durch Innovative und Präventive Sozialpolitik; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Ed.; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Bonn, Germany, 2013; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Blätte, A.; Zitzler, S. Vorsorgende Sozialpolitik als sozialpolitisches Leitbild der SPD. In Die Ökonomisierung der Politik in Deutschland: Eine Vergleichende Politikfeldanalyse; Schaal, G.S., Lemke, M., Ritzi, C., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2014; pp. 69–95. [Google Scholar]

- Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kinder- und Jugendhilfe (AGJ). Stärkung Präventiver Arbeit in der Kinder- und Jugendhilfe; Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kinder- und Jugendhilfe: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scherr, A. Prävention. In Kompendium Kinder- und Jugendhilfe; Böllert, K., Ed.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 1013–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Böllert, K. Prävention und Intervention. In Handbuch Soziale Arbeit: Grundlagen der Sozialarbeit und Sozialpädagogik; Otto, H.-U., Thiersch, H., Treptow, R., Ziegler, H., Eds.; Ernst Reinhardt Verlag: München, Germany, 2018; pp. 1394–1398. [Google Scholar]

- Soziales, B. Lebenslagen in Deutschland. Der 4. Armuts- und Reichtumsbericht der Bundesregierung; Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales: Bonn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales (BMAS). Der Vierte Armuts- und Reichtumsbericht der Bundesregierung; Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Naegele, G. Soziale Lebenslaufpolitik—Grundlagen, Analysen und Konzepte. In Soziale Lebenslaufpolitik; Naegele, G., Ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; pp. 27–85. [Google Scholar]

- Naegele, G.; Olbermann, E.; Bertermann, B. Altersarmut als Herausforderung für die Lebenslaufpolitik. In Altern im Sozialen Wandel: Die Rückkehr der Altersarmut? Vogel, C., Motel-Klingebiel, A., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Klenner, C.; Buschoff, K.S. Vielfältige Optionen eröffnen, gesicherte ͨbergänge gestalten: Veränderte Erwerbsverläufe und Lebenslaufpolitik. In Arbeit der Zukunft: Möglichkeiten Nutzen-Grenzen Setzen; Hoffmann, R., Bogedan, C., Eds.; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, H. Netzwerkmanagement in Kommune und Sozialwirtschaft; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J. Netzwerkorientiertes Handeln in der kommunalen Bildungs- und Sozialpolitik. In Netzwerke und Soziale Arbeit: Theorien, Methoden, Anwendungen; Fischer, J., Kosellek, T., Eds.; Beltz Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2019; pp. 461–475. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K. Handbuch Sozialraumorientierung; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Richter-Kornweitz, A.; Utermark, K. Werkbuch Präventionskette. Herausforderungen und Chancen beim Aufbau von Präventionsketten in Kommunen; Niedersächsischen Koordinierungsstelle Gesundheitliche Chancengleichheit: Hannover, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens, J.; Cierpka, M.; Franzkowiak, P.; Hilgers, H.; Maywald, J.; Thyen, U. Leitbild Frühe Hilfen. Beitrag des BZFH-Beitrats. 2009. Available online: https://www.fruehehilfen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fruehehilfen.de/pdf/Publikation_NZFH_Kompakt_Beirat_Leitbild_fuer_Fruehe_Hilfen.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Nationale Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH). Netzwerke Frühe Hilfen. Available online: https://www.fruehehilfen.de/grundlagen-und-fachthemen/netzwerke-fruehe-hilfen/ (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Sann, A.; Küster, E.-U.; Pabst, C.; Peterle, C. Entwicklung der Frühen Hilfen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse der NZFH-Kommunalbefragungen im Rahmen der Dokumentation und Evaluation der Bundesinitiative Frühe Hilfen (2013–2017); NZFH: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (BIBB). Berufsbildungsbericht 2010; 978-3-88555-877-4; Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung: Bonn, Germany, 2010.

- Kowalczyk, K.; Oschmiansky, F.; Popp, S.; Borchers, A.; Kukat, M.; Seidel, S.; Bennewitz, H.; Muhl, L.; Siebert, J. Externe Evaluation der BMBF-Initiative “Abschluss und Anschluss—Bildungs-Ketten bis zum Ausbil-Dungsabschluss” Endbericht. 2014. Available online: http://www.bildungsketten.de/_media/Externe_Evaluation_Initiative_Bildungsketten_Endbericht_mit_Anhang.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Taffertshofer, B. Bildungsgipfel—Die Macher Blieben Daheim. Available online: https://www.bmbf.de/bmbf/de/bildung/bildungsforschung/aufstieg-durch-bildung/aufstieg-durch-bildung_node.html (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Bundesregierung, D. Aufstieg Durch Bildung. Die Qualifizierungsinitiative für Deutschland. 2008. Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/pdf/Bildung/AllgBildung/2008-10-22-Qualifizierungsinitiative.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Borchers, A.; Rödiger, L.; Seidel, S.; Ebach, M.; Kaps, P.; Kowalczyk, K.; Oschmiansky, F.; Popp, S. Evaluation der Initiative “Abschluss und Anschluss—Bildungsketten bis zum Ausbildungsabschluss”: Erfolgreiche Übergänge in die betriebliche Ausbildung; Institut für Entwicklungsplanung und Strukturforschung GmbH an der Universität Hannover (ies), Zentrum für Evaluation und Politikberatung (ZEP): Hannover und Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heisig, K.; Sonnenburg, J. Schulabgänger ohne Abschluss: Wodurch lassen sich die Unterschiede zwischen Ost und Westdeutschland erklären? Ifo Dresd. Berichtet 2017, 24, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Berufsbildung, B.F. Datenreport zum Berufsbildungsbericht 2021. Informationen und Analysen zur Entwicklung der beruflichen Bildung; Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung: Bonn, Germany, 2021. Available online: https://www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/bibb-datenreport-2021.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (BMFSFJ). Lokale Bündnisse Machen “Stark für Familienmomente”. Available online: https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/aktuelles/alle-meldungen/lokale-buendnisse-machen-stark-fuer-familienmomente--224612 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Hammermann, A.; Schmidt, J.; Stettes, O. Unternehmensmonitor Familienfreundlichkeit 2019; Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln (IW): Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrentraut, O.; Hackmann, T.; Krämer, L.; Schmutz, S. Zukunft der Pflegepolitik. Perspektiven, Handlungsoptionen und Politikempfehlungen; Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Bonn, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Krupp, E.; Hielscher, V. Wissenschaftliche Evaluation der Umstellung des Verfahrens zur Feststellung der Pflegebedürftigkeit; Bundesministerium für Gesundheit: Berlin, Germany, 2019.

- Arbeit, B.F. Fachkräfteengpassanalyse 2019; Bundesagentur für Arbeit: Nürnberg, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/Statistikdaten/Detail/201912/arbeitsmarktberichte/fk-engpassanalyse/fk-engpassanalyse-d-0-201912-pdf.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz (BMWK). Erfolgsmodell für die Pflegebranche. In Auszubildende aus Drittstaaten für die Pflege in Deutschland Gewinnen; Ein Leitfaden mit Handlungsempfehlungen: Berlin, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Schlaglichter-der-Wirtschaftspolitik/2020/04/kapitel-1-8-erfolgsmodell-fuer-die-pflegebranche.html (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat. Demografiepolitik im Querschnitt. Résumé des Bundesministeriums des Innern, für Bau und Heimat zum Ende der 19. Legislaturperiode: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://www.demografie-portal.de/DE/Publikationen/2021/demografiepolitik-im-querschnitt-resume-bmi.html (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Zhai, Z. Interpretation of the Seventh China National Population Census Communiqué. 2021. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1699522619476508478&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 25 August 2023).

- Nordrhein-Westfalen, L. Gemeinsamer Aufruf der Programme des EFRE, des ELER und des ESF (2014–2020) zur Präventiven und Nachhaltigen Entwicklung von Quartieren und Ortsteilen sowie zur Bekämpfung von Armut und Ausgrenzung. 2015. Available online: https://www.efre.nrw.de/wege-zur-foerderung/projektaufrufe/starke-quartiere-starke-menschen/ (accessed on 25 August 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).