Impact of E-Commerce and Digital Marketing Adoption on the Financial and Sustainability Performance of MSMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.2. E-commerce Adoption

2.3. Digital Marketing Adoption

2.4. Firm Performance and Sustainability

3. Research Methods

3.1. Measures

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

3.3. Respondents’ Profile

3.4. Data Analysis Technique

4. Results

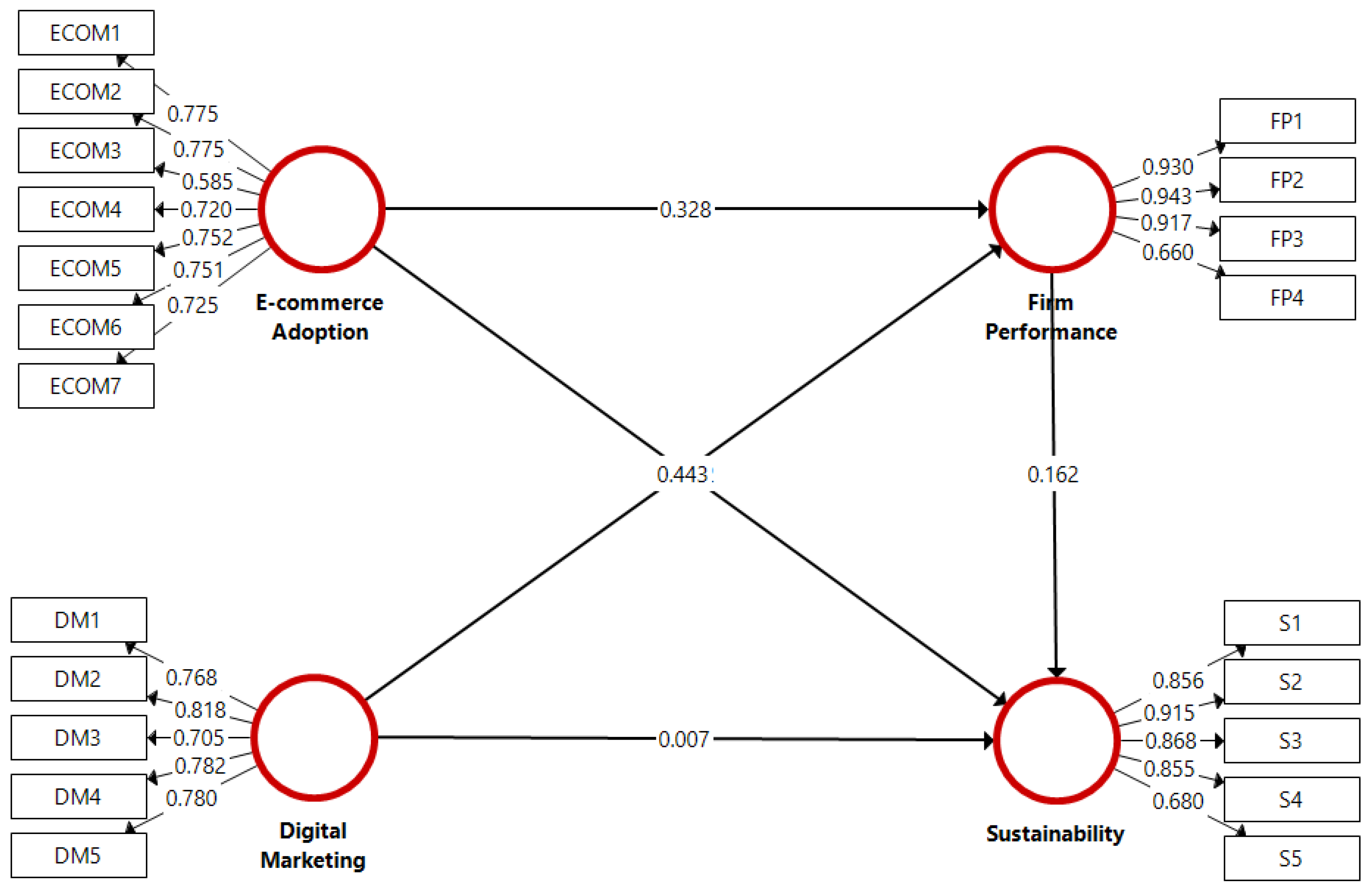

4.1. Measurement Model

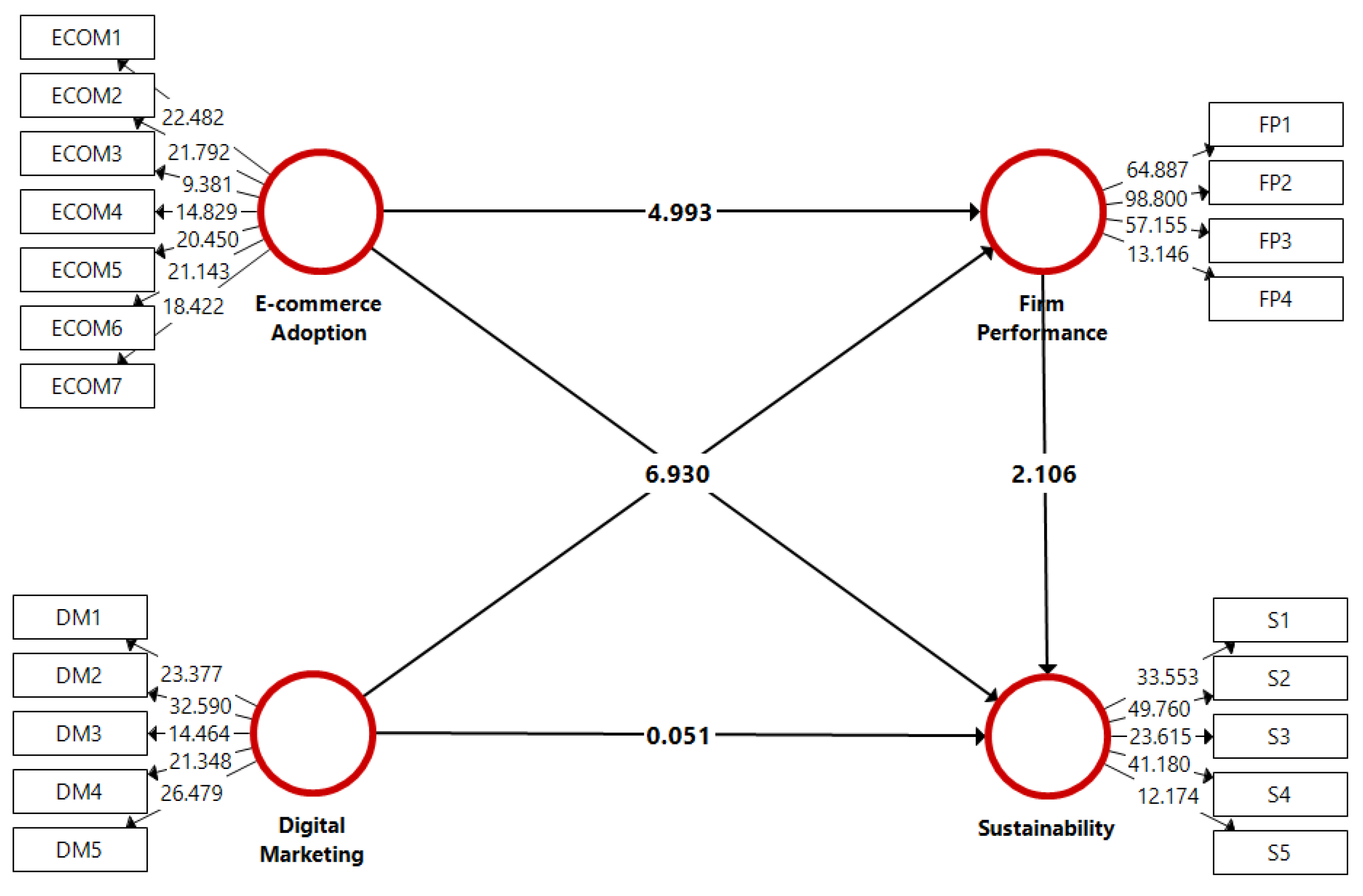

4.2. Results of Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martin, L.M.; Matlay, H. Innovative use of the Internet in established small firms: The impact of knowledge management and organisational learning in accessing new opportunities. Qual. Mark. Res. 2003, 6, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, S.A.; Regan, E.A. Factors Influencing e-commerce Adoption and Use by Small and Medium Businesses. Electron. Mark. 2005, 15, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, M. Electronic commerce adoption, entrepreneurial orientation and small-and medium-sized enterprise (SME) performance. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2014, 21, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tong, D.; Huang, J.; Zheng, W.; Kong, M.; Zhou, G. What matters in the e-commerce era? Modelling and mapping shop rents in Guangzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2022, 123, 106430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Mao, H.; Zhao, T.; Wang, V.L.; Wang, X.; Zuo, P. How B2B platform improves Buyers’ performance: Insights into platform’s substitution effect. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 143, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomin, V.V.; King, J.L.; Lyytinen, K.J.; McGann, S.T. Diffusion and Impacts of E-Commerce in the United States of America: Results from an Industry Survey. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 559–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qirim, N.A.Y. The Strategic Outsourcing Decision of IT and eCommerce: The Case of Small Businesses in New Zealand. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2003, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K. The Complementarity of Information Technology Infrastructure and E-Commerce Capability: A Resource-Based Assessment of Their Business Value. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2004, 21, 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qirim, N. The adoption of eCommerce communications and applications technologies in small businesses in New Zealand. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2007, 6, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandon, E.E.; Pearson, J.M. Electronic commerce adoption: An empirical study of small and medium US businesses. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, R.C.; Vrazalic, L. A basic model of electronic commerce adoption barriers: A study of regional small businesses in Sweden and Australia. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2005, 12, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, H. Commercial Internet adoption in China: Comparing the experience of small, medium and large businesses. Internet Res. 2002, 12, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacob, S.; Sulistiyo, U.; Erida, E.; Siregar, A.P. The importance of E-commerce adoption and entrepreneurship orientation for sustainable micro, small, and medium enterprises in Indonesia. Dev. Stud. Res. 2021, 8, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A.; Gallagher, D.; Henry, S. E-marketing and SMEs: Operational lessons for the future. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2007, 19, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, W.; Wolf, M.; McQuitty, S. Digital marketing adoption and success for small businesses: The application of the do-it-yourself and technology acceptance models. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2019, 13, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R.; Palacios-marqués, D.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Digital marketing in SMEs via data-driven strategies: Reviewing the current state of research. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Siamagka, N.T.; Christodoulides, G. Usage, barriers and measurement of social media marketing: An exploratory investigation of small and medium B2B brands. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, A.A.; Rana, N.A.; Inam, A.; Shahzad, A.; Awan, H.M. Is e-marketing a source of sustainable business performance? Predicting the role of top management support with various interaction factors. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1516487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, S. The importance of social media and digital marketing to attract millennials’ behavior as a consumer. J. Int. Bus. Res. Mark. 2019, 4, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, C.L.; Liu, J.; Zhou, L. Why do consumers prefer a hometown geographical indication brand? Exploring the role of consumer identification with the brand and psychological ownership. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zhou, L.; Hu, X. Development Countermeasures of International E-Commerce Based on Network Consumption Psychology. Psychiatr. Danub. 2021, 33, 139–140. [Google Scholar]

- Qamruzzaman, M.; Jianguo, W. SME financing innovation and SME development in Bangladesh: An application of ARDL. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2019, 31, 521–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LightCastle Analytics Wing COVID-19: Impact on Bangladesh’s SME Landscape. 2020. Available online: https://www.lightcastlebd.com/insights/2020/04/covid-19-impact-on-bangladeshs-sme-landscape/ (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Aghaei, I.; Sokhanvar, A. Factors influencing SME owners’ continuance intention in Bangladesh: A logistic regression model. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2020, 10, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasima, S.; Rahman, M.N. Economic Vulnerability of the Underprivileged during the COVID Pandemic: The Case of Bangladeshi Domestic Workers. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2022, 48, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, D.; Micozzi, A.; Spigarelli, F. Industry 4.0 Accelerating Sustainable Manufacturing in the COVID-19 Era: Assessing the Readiness and Responsiveness of Italian Regions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhan, X.; BalaMurugan, S.; Thilak, K.D. Improved policy mechanisms for the promotion of future digital business economy during covid-19 pandemic. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyono, A.; Moin, A.; Putri, V.N.A.O. Identifying Digital Transformation Paths in the Business Model of SMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Obrenovic, B.; Du, J.; Godinic, D.; Khudaykulov, A. COVID-19 Pandemic Implications for Corporate Sustainability and Society: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.N.; Mona, S.S.; Noman, S.A.A.; Avi, A. Das COVID-19, Consumer Behavior and Inventory Management: A Study on the Retail Pharmaceutical Industry of Bangladesh. Supply Chain Insid. 2020, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bussolo, M.; Sharma, S. E-commerce is creating growth opportunities for small businesses in South Asia. World Bank Blogs. 9 February 2022. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/e-commerce-creating-growth-opportunities-small-businesses-south-asia (accessed on 26 October 2022).

- Ciunici, C. Digital Marketing Vital in a Post-COVID-19 World. 2021. Available online: https://www.sme.org/technologies/articles/2021/july/digital-marketing-vital-in-a-post-covid-19-world/ (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Newbert, S.L. Empirical research on the resource-based view of the firm: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voola, R.; Casimir, G.; Carlson, J.; Agnihotri, M.A. The effects of market orientation, technological opportunism, and e-business adoption on performance: A moderated mediation analysis. Australas. Mark. J. 2012, 20, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, D.; Barney, J.B. Perspectives in Organizations: Resource Dependence, Efficiency, and Population1. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E. The Theory of Growth of the Firm; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Liem, N.T.; Khuong, N.V.; Khanh, T.H.T. Firm Constraints on the Link between Proactive Innovation, Open Innovation and Firm Performance. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Shahzad, A.; Hassan, R. Organizational and environmental factors with the mediating role of e-commerce and SME performance. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, J.Š.; Vujadinovic, R.; Mitreva, E.; Fragassa, C.; Vujovic, A. The relationship between E-commerce and firm performance: The mediating role of internet sales channels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrigot, R.; Pénard, T. Determinants of E-Commerce Strategy in Franchising: A Resource-Based View. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2014, 17, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubacher, R.J.; Malone, T.W. The Dawn of the E-lance Economy. In Electronic Business Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Straub, D.; Klein, R. E-competitive transformations. Bus. Horiz. 2001, 44, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallone, T.; Elia, S.; Greve, P.; Longoni, L.; Marinelli, D. Top management team influence on firms’ internationalization complexity. In Progress in International Business Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; Volume 14, pp. 199–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, D.; Risselada, A.; Spierings, B.; Weltevreden, J.W.J.; Atzema, O. Digital marketing activities by Dutch place management partnerships: A resource-based view. Cities 2022, 123, 103548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, E. Electronic Commerce 2010: A Managerial Perspective; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kalakota, R.; Whinston, A. Electronic Commerce: A Manager’s Guide; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hurley, R.F.; Knight, G.A. Innovativeness: Its antecedents and impact on business performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.N.; Zhong, W.J.; Mei, S.E. Application capability of e-business, e-business success, and organizational performance: Empirical evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2011, 78, 1412–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyskens, I.; Gielens, K.; Dekimpe, M.G. The Market Valuation of Internet Channel Additions. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Mahajan, V.; Balasubramanian, S. An analysis of e-business adoption and its impact on business performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2003, 31, 425–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.S.H.; Pian, Y. A contingency perspective on Internet adoption and competitive advantage. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2003, 12, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garicano, L.; Kaplan, S.N. The Effects of Business-to-Business E-Commerce on Transaction Costs. J. Ind. Econ. 2001, 49, 463–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigand, R.T.; Benjamin, R.I. Electronic Commerce: Effects on Electronic Markets. J. Comput. Commun. 1995, 1, JCMC133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohrke, F.T.; Franklin, G.M.C.; Frownfelter-Lohrke, C. The Internet as an Information Conduit: A Transaction Cost Analysis Model of US SME Internet Use. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2006, 24, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, E.; D’Altri, S. The Diffusion of E-commerce among SMEs: Theoretical Implications and Empirical Evidence. Small Bus. Econ. 2003, 21, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, H. Internationalization of small and medium-sized enterprises: A grounded theoretical framework and an overview. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2004, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, R.; Wigand, R.; König, W. The Diffusion and Efficient Use of Electronic Commerce among Small and Medium-sized Enterprises: An International Three-Industry Survey. Electron. Mark. 2005, 15, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oláh, J.; Kitukutha, N.; Haddad, H.; Pakurár, M.; Máté, D.; Popp, J. Achieving Sustainable E-Commerce in Environmental, Social and Economic Dimensions by Taking Possible Trade-Offs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Gao, D. The role of intermediation in the governance of sustainable Chinese web marketing. Sustainability 2014, 6, 4102–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C.; Hallstedt, S.; Robèrt, K.H.; Broman, G.; Oldmark, J. Assessment of eco-labelling criteria development from a strategic sustainability perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, H.; Azevedo, S.G.; Duarte, S.; Cruz-Machado, V. Green and Lean Paradigms Influence on Sustainable Business Development of Manufacturing Supply Chains. Int. J. Green Comput. 2011, 2, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, N. Does e-commerce provide a sustained competitive advantage? An investigation of survival and sustainability in growth-oriented enterprises. Sustainability 2015, 7, 1411–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiaracina, R.; Marchet, G.; Perotti, S.; Tumino, A. A review of the environmental implications of B2C e-commerce: A logistics perspective. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 565–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Harms, R.; Fink, M. Entrepreneurial marketing: Moving beyond marketing in new ventures. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2010, 11, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahto, R.V.; McDowell, W.C. Entrepreneurial motivation: A non-entrepreneur’s journey to become an entrepreneur. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.T. Longitudinal study of digital marketing strategies targeting Millennials. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celuch, K.; Murphy, G. SME Internet use and strategic flexibility: The moderating effect of IT market orientation. J. Mark. Manag. 2010, 26, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanassova, I.; Clark, L. Social media practices in SME marketing activities: A theoretical framework and research agenda. J. Cust. Behav. 2015, 14, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Newby, M.; Macaulay, M.J. Information Technology Adoption in Small Business: Confirmation of a Proposed Framework. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2015, 53, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.T.; Hultman, J.; Naldi, L. Small business e-commerce development in Sweden–an empirical survey. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2008, 15, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Siddik, A.B.; Akter, N.; Dong, Q. Factors influencing the adoption intention of using mobile financial service during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of FinTech. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordonaba-juste, V.; Lucia-palacios, L.; Polo-redondo, Y. The influence of organizational factors on e-business use: Analysis of firm size. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, R.R.; Kshetri, N. Factors Impacting the Adoption of the Internet among SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2004, 23, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockett, A.; Thompson, S. The resource-based view and economics. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 723–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstoy, D.; Rovira, E.; Vu, U. The indirect effect of online marketing capabilities on the international performance of e-commerce SMEs. Int. Bus. Rev. 2022, 31, 101946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, D.; Cromie, S.; McGowan, P.; Hill, J. Marketing and Entrepreneurship in SMEs: An Innovative Approach; Prentice-Hall: Harlow, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Herbig, P.; Hale, B. Internet: The marketing challenge of the twentieth century. Internet Res. 1997, 7, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, V.; Tatoglu, E. An exploratory study of internet adoption by SMEs in an emerging economy. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2003, 15, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Winklhofer, H.; Coviello, N.E.; Johnston, W.J. Is e-marketing coming of age? An examination of the penetration of e-marketing and firm performance. J. Interact. Mark. 2007, 21, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidek, S.; Rosli, M.M.; Khadri, N.A.M.; Hasbolah, H.; Manshar, M.; Abidin, N.M.F.N.Z. Fortifying Small Business Performance Sustainability in The Era Of IR 4.0: E-Marketing As a Catalyst of Competitive Advantages and Business Performance. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 2143–2155. [Google Scholar]

- Saura, J.R.; Palos-sanchez, P. Digital Marketing for Sustainable Growth: Business Models and Online Campaigns Using Sustainable Strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffey, D.; Ellis-Chadwick, F. Digital Marketing; Pearson: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitriu, D.; Militaru, G.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Niculescu, A.; Popescu, M.A.-M. A Perspective Over Modern SMEs: Managing Brand Equity, Growth and Sustainability Through Digital Marketing Tools and Techniques. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivarajah, U.; Irani, Z.; Gupta, S.; Mahroof, K. Role of big data and social media analytics for business to business sustainability: A participatory web context. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 86, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Fatema, N. Factors Affecting the Sustainability Performance of Financial Institutions in Bangladesh: The Role of Green Finance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozman, D.; Willcocks, L. The emerging Cloud Dilemma: Balancing innovation with cross-border privacy and outsourcing regulations. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 97, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiach, T.; Lee, D.; Nelson, D.; Walker, J. The determinants of corporate sustainability performance. Account. Financ. 2010, 50, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Does it really pay to be green? Determinants and consequences of proactive environmental strategies. J. Account. Public Policy 2011, 30, 122–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrenovic, B.; Du, J.; Godinic, D.; Tsoy, D.; Khan, M.A.S.; Jakhongirov, I. Sustaining Enterprise Operations and Productivity during the COVID-19 Pandemic: “Enterprise Effectiveness and Sustainability Model”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmann, P. Effects of “Best Practices” of Environmental Management on Cost Advantage: The Role of Complementary Assets. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Balasubramanian, S.; Vihari, N.; Jabeen, S.; Shukla, V.; Chanchaichujit, J. The e-commerce supply chain and environmental sustainability: An empirical investigation on the online retail sector. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1938377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Sharma, S.K.; Swami, S. Antecedents and consequences of organizational politics: A select study of a central university. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2016, 13, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.L.; Kraemer, K.L. A Cross-Country Investigation of the Determinants of Scope of E-commerce Use: An Institutional Approach. Electron. Mark. 2004, 14, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Afum, E.; Ahenkorah, E. Exploring financial performance and green logistics management practices: Examining the mediating influences of market, environmental and social performances. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Salisu, I.; Aslam, H.D.; Iqbal, J.; Hameed, I. Resource and Information Access for SME Sustainability in the Era of IR 4.0: The Mediating and Moderating Roles of Innovation Capability and Management Commitment. Process 2019, 7, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Riel, A.C.R.; Henseler, J.; Kemény, I.; Sasovova, Z. Estimating hierarchical constructs using consistent partial least squares of common factors. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Wei, X. Bridging Green Gaps: The Buying Intention of Energy Efficient Home Appliances and Moderation of Green Self-Identity. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.W.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M.; Alam, S.S.; Akter, A. Perceived environmental responsibilities and green buying behavior: The mediating effect of attitude. Sustainability 2021, 13, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Mustafi, M.A.A.; Rahman, M.N.; Nower, N.; Rafi, M.M.A.; Natasha, M.T.; Hassan, R.; Afrin, S. Factors Affecting Customers’ Experience in Mobile Banking of Bangladesh. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2019, 19, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdaous, D.J.; Rahman, M.N. Banking Goes Digital: Unearthing the Adoption of Fintech by Bangladeshi Households. J. Innov. Bus. Stud. 2021, 1, 7–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.N.; Nower, N.; Hassan, R.; Samiha, Z. An Evaluation of the Factors Influencing Customers’ Experience in Supermarkets of Bangladesh. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Roldán, J.L.; Sánchez-Franco, M.J. Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling: Guidelines for Using Partial Least Squares in Information Systems Research. In Research Methodologies, Innovations and Philosophies in Software Systems Engineering and Information Systems; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 193–221. ISBN 9781466601796. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias: A Full Collinearity Assessment Method for PLS-SEM. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications; Latan, H.N.R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 245–257. ISBN 9783319640693. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence-Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Holgersson, M. Patent management in entrepreneurial SMEs: A literature review and an empirical study of innovation appropriation, patent propensity, and motives. R&D Manag. 2013, 43, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Siddik, A.B.; Zheng, G.-W.; Masukujjaman, M.; Bekhzod, S. The Effect of Green Banking Practices on Banks’ Environmental Performance and Green Financing: An Empirical Study. Energies 2022, 15, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.H.M.B.; Endut, N.; Das, S.; Chowdhury, M.T.A.; Haque, N.; Sultana, S.; Ahmed, K.J. Does financial inclusion increase financial resilience? Evidence from Bangladesh. Dev. Pract. 2019, 29, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yang, H.; Sun, L.; Sohal, A.S. The impact of IT implementation on supply chain integration and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 120, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, I.; Nurjannah, D.; Mohyi, A.; Ambarwati, T.; Cahyono, Y.; Haryoko, A.E.; Handoko, A.L.; Putra, R.S.; Wijoyo, H.; Ariyanto, A.; et al. The effect of digital marketing, digital finance and digital payment on finance performance of Indonesian SMEs. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setkute, J.; Dibb, S. “Old boys’ club”: Barriers to digital marketing in small B2B firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 102, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Kumar Kar, A. Why do small and medium enterprises use social media marketing and what is the impact: Empirical insights from India. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.; Haase, H.; Pereira, A. Empirical study about the role of social networks in SME performance. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2016, 18, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, A.; Tasneem, S.; Fatema, K. Effectiveness of Digital Marketing in the Challenginging Age: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Adm. 2015, 1, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cenamor, J.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. How entrepreneurial SMEs compete through digital platforms: The roles of digital platform capability, network capability and ambidexterity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbreviation | Explanation |

|---|---|

| MSME | Micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises |

| EC | E-commerce |

| ECA | E-commerce adoption |

| DM | Digital marketing |

| DMA | Digital marketing adoption |

| PLS-SEM | Partial least squares structural equation modeling |

| TCE theory | Transaction-cost economics theory |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| CR | Composite reliability |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

| HTMT | Heterotrait-monotrait correlation ratio |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Marketing | DM1 | 0.768 | 0.831 | 0.880 | 0.595 |

| DM2 | 0.818 | ||||

| DM3 | 0.705 | ||||

| DM4 | 0.782 | ||||

| DM5 | 0.780 | ||||

| E-commerce Adoption | ECOM1 | 0.775 | 0.852 | 0.887 | 0.531 |

| ECOM2 | 0.775 | ||||

| ECOM3 | 0.585 | ||||

| ECOM4 | 0.720 | ||||

| ECOM5 | 0.752 | ||||

| ECOM6 | 0.751 | ||||

| ECOM7 | 0.725 | ||||

| Firm Performance | FP1 | 0.930 | 0.886 | 0.925 | 0.758 |

| FP2 | 0.943 | ||||

| FP3 | 0.917 | ||||

| FP4 | 0.660 | ||||

| Sustainability | S1 | 0.856 | 0.892 | 0.922 | 0.703 |

| S2 | 0.915 | ||||

| S3 | 0.868 | ||||

| S4 | 0.855 | ||||

| S5 | 0.680 |

| Digital Marketing | E-commerce Adoption | Firm Performance | Sustainability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Marketing | 0.771 | |||

| E-commerce Adoption | 0.414 | 0.729 | ||

| Firm Performance | 0.579 | 0.511 | 0.87 | |

| Sustainability | 0.225 | 0.387 | 0.32 | 0.839 |

| Digital Marketing | E-Commerce Adoption | Firm Performance | Sustainability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Marketing | ||||

| E-commerce Adoption | 0.480 | |||

| Firm Performance | 0.657 | 0.582 | ||

| Sustainability | 0.251 | 0.433 | 0.364 | |

| Hypotheses | Coefficients | t-Statistics | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: E-commerce Adoption ➔ Firm Performance | 0.332 (0.066) *** | 4.993 | Supported |

| H2: E-commerce Adoption ➔ Sustainability | 0.307 (0.083) *** | 3.622 | Supported |

| H3: Digital Marketing ➔ Firm Performance | 0.444 (0.064) *** | 6.93 | Supported |

| H4: Digital Marketing ➔ Sustainability | 0.005 (0.091) | 0.051 | Not supported |

| H5: Firm Performance ➔ Sustainability | 0.161 (0.077) ** | 2.106 | Supported |

| H6: E-commerce Adoption ➔ Firm Performance ➔ Sustainability | 0.053 (0.028) ** | 1.914 | Supported |

| H7: Digital Marketing ➔ Firm Performance ➔ Sustainability | 0.071 (0.036) ** | 2.006 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, J.; Siddik, A.B.; Khawar Abbas, S.; Hamayun, M.; Masukujjaman, M.; Alam, S.S. Impact of E-Commerce and Digital Marketing Adoption on the Financial and Sustainability Performance of MSMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021594

Gao J, Siddik AB, Khawar Abbas S, Hamayun M, Masukujjaman M, Alam SS. Impact of E-Commerce and Digital Marketing Adoption on the Financial and Sustainability Performance of MSMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Study. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021594

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Jianli, Abu Bakkar Siddik, Sayyed Khawar Abbas, Muhammad Hamayun, Mohammad Masukujjaman, and Syed Shah Alam. 2023. "Impact of E-Commerce and Digital Marketing Adoption on the Financial and Sustainability Performance of MSMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Study" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021594

APA StyleGao, J., Siddik, A. B., Khawar Abbas, S., Hamayun, M., Masukujjaman, M., & Alam, S. S. (2023). Impact of E-Commerce and Digital Marketing Adoption on the Financial and Sustainability Performance of MSMEs during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Study. Sustainability, 15(2), 1594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021594