Abstract

With the advent of the digital economy era, the relationship between consumers and brands is changing. The mode of marketing, especially the paradigm of brand management, also needs to be adapted to change. Brand orientation has triggered a heated discussion on the dominant paradigm of market orientation and a new revolution in brand management. In view of the primary position of brand orientation in the management domain, it is necessary to sort out a systematic scientific knowledge mapping, clarify the research context and progress, and discover research focuses and limitations for strengthening the construction of brand-oriented theories. This study conducts a scientific quantitative analysis of 169 literatures and 7187 references from the Web of Science in the field of brand orientation by comprehensively using methods of scientific knowledge mapping and traditional literature review. The findings show that: (1) Concentrating on the core issue that “whether and how brand orientation becomes an effective strategic orientation of an organization”, brand orientation research includes six major hot spots and has been extended to fields including non-profit organizations, retail, service, manufacturing, e-commerce, and tourism. (2) As a multi-dimensional construct, brand orientation affects organizational performance directly through internal branding and external customer perception, and it is influenced by organizational culture, leadership, competition environment, funding sources, and brand cooperation. The relationship between brand orientation and market orientation has evolved from mutual substitution to synergy.

1. Introduction

In the digital economy, digital technology platforms provide channels for brands to establish direct connections with users, and brands and users start to establish a disintermediary relationship. That is, users’ personal capabilities, integration, and experience participate in the brand-building process and play a decisive role; enterprises interact with consumers directly through social media, e-commerce platforms, APPs, and other channles to jointly create brand equity. In the digital world, brands can spread more quickly among core consumer groups, which is contrary to the traditional path of brand building. The boundary of the brand has been expanded; it not only extends within the scope of business, but it also can further expand into a brand ecosystem in the digital economy. The form of a brand ecosystem could improve the stability of the brand and stimulate the vitality. In addition, brand value concept and brand experience, which are more able to attract consumers, have become the core competitiveness of the brand [1].

Urde [2] put forward the new concept and paradigm of “brand orientation”, which considers that “brand orientation is an approach in which the processes of the organization revolve around the creation, development and protection of brand identity in an ongoing interaction with target customers with the aim of achieving lasting competitive advantages in the form of brands” [3]. Brand orientation is a mindset for building brands strategically, which uses the brand as the starting point and puts brand-related resources at the heart of the strategic process. Experiences of the case studies carried out by Urde [3] show that the brand can be braided into a brand identity through a process of value creation and meaning creation by combining the brand with other assets and competencies within the company. The brand identity constitutes a collective picture or form and answers the question “Who is the brand?”. The concept of identity is central to a brand-oriented organization and provides an understanding of the lasting inner values. This brand identity will be experienced by customers as valuable and unique and is difficult for competitors to imitate. Therefore, the objective of a brand-oriented organization is to create value and meaning within the framework of the brand, and the fundamental process in such organizations is to transform products into brands with internal significance for the organization itself and for the target group. Accordingly, a product fulfils a function, whereas a brand symbolizes values and meaning in a social context [4,5].

Brand orientation, as a challenge to the dominant paradigm in the management field for more than 50 years [6], has triggered a heated discussion on the dominant paradigm of market orientation and a new revolution in brand management. Urde et al. [7] emphasized the strategic importance of brand orientation and described it as “a new approach to brands that focuses on brands as resources and strategic hubs”. Due to the critical position of brand orientation in enterprise management and strategy formulation, a large number of scholars have carried out a series of studies on the concept and structure [2,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. For example, Hankinson [12] addressed that brand orientation is the extent to which the organization regarded itself as a brand and accepted the brand theory and brand practice. Gromark and Melin [11] considered that brand orientation is a brand-building approach that creates brand equity through the interaction between internal and external stakeholders. Regarding the content structure of brand orientation, scholars conceptualized brand orientation into several different multidimensional structures on the basis of the recognition of brand importance [16], common brand meaning [10], brand capabilities [9,17], enterprise culture [8,13], modes of thinking or mindset [11,14,15,18], organizational processes [3,10], organizational practices and behavior [9,13,17], and so on.

There are also a large number of empirical studies that have verified that brand orientation has positive relationships with organization survival [2], organization growth [19,20], brand equity [21,22,23,24], and organization performance [8,11,13,15,25,26,27]. Therefore, it is commonly believed that brand-oriented marketing efforts yield brand-related performance gains, such as winning loyal customers, increasing brand awareness, good reputation, positive image [15,25], and overall market improvement performance [28]. For example, Baumgrth and Schmidt [21] and Azizi et al. [29] have found a huge impact of brand-oriented corporate culture on internal brand equity in their proposed model, which indicated that with the increasing brand orientation of the organization, employee’s loyalty toward the organization’s brand will increase. As a result, this will result in employee behavior being more aligned with the organizational brand, which in turn can improve employee performance to meet customer expectations.

Although the important value of brand orientation is emphasized [21,29], the research on brand orientation is still few, controversial, and insufficient. Specifically, this includes: the definition and measurement of brand orientation have not been unified; the debate between brand orientation and market orientation is still going on; the impact of brand orientation on organizational performance is different in different organizational types. For example, Hirvonen and Laukkanen’s [30] research on Finnish small service companies and studies of Boso et al. [31] based on a sample of 108 multinational enterprises in the Commonwealth Caribbean demonstrated that brand orientation exerts no direct influence on enterprise performance. Research on B2B SMEs by Hirvonen et al. [32] proved that brand orientation has no significant direct impact on brand performance and exerts weak influence on the business growth, which is different from the findings of Melewar and Baumgarth’s research [13]. In addition, Chang et al. [33] explored the positive effects of organizational resources on brand orientation for manufacturing enterprises, whereas the research of Huang and Tsai [34] discovered that the abundance of organizational resources have no significant effect on brand orientation. This indicates that the research results on brand orientation have not reached an agreement and are still in the preliminary exploration stage. Therefore, it is necessary to sort out a systematic scientific knowledge mapping, clarify the research context and progress, and discover research limitations for strengthening the construction of brand orientation theories.

At present, there are only a few literature reviews in the brand-oriented field. For example, Baumgarth et al. [6] summarized the origin, current progress, and future research direction of brand orientation based on studies about leadership, management, internal construction and processes, and complex implementation methods of brand-oriented organizations, which were published in the special issue of Journal of Marketing Management in 2011; Chabowski’s [35] bibliometric analysis of 120 articles on the global branding literature (GBL) in business-related research pointed out that brand orientation is an important knowledge base of GBL and is one of the main research topics of GBL, which is of great significance to the future development of global brands. Balmer [36] outlined the perspectives, canon, and symptomatic ‘schools of thought’ of brand orientation when he formally introduces the corporate brand orientation notion. Anees-ur-Rehman et al. [37] have reviewed the research progress in the field of brand orientation in Australia in the past 20 years by systematic literature review. Sepulcri et al. [38] conducted a bibliometric analysis based on 90 articles in the Scopus database, and they identified and discussed five main areas of research on brand orientation, including brand positioning concept, hybrid strategy, internal brand management, brand performance, and perceived brand positioning. The above literature reviews are based on the research results published in a particular journal [6], in a certain database [38], on one specific research topic [35,36], or on a specific country/region [37], giving rise to some limitations in the basis and methods of the literature analysis. In particular, although Chabowski [35] and Sepulcri [38] have applied bibliometric analysis to brand orientation-related fields, specific research topics and specific databases lead to the limitations of their research conclusions. In terms of research methods, existing studies have adopted a single research method, such as a purely traditional literature review approach or a pure bibliometric analysis, which gives rise to the deficiency of scientific, systematic, and precise literature reviews in this field.

Both the traditional literature review and the bibliometric method emphasize the collation of previous research in order to discover the current status, shortcomings, and prospects of the research. Traditional literature review puts more emphasis on content and usually selects representative papers and writes them according to the preset research context. As a new method and field of scientometrics, bibliometric analysis takes knowledge domain as the object and adopts integrated methods, including the application of applied mathematics, graphics, information visualization, information science, citation analysis, and co-occurrence analysis to illustrate the core structure, the development history, frontier domains, and the overall knowledge framework [39,40], providing practical and valuable references for the scientific research.

Correspondingly, this study conducts a scientific quantitative analysis of 169 literatures and 7187 references from the WOS database, using the method of scientific knowledge mapping, as well as other literatures from the Scopus database in the field of brand orientation, using the method of traditional literature review. This study aims to evaluate the research that has been published on brand orientation between the years 1990–2021 (including three early access articles in 2022) by addressing four research questions:

- RQ1: What was the distribution of research findings related to brand orientation during the survey period?

- RQ2: What are the main research clusters of brand orientation and their hot areas?

- RQ3: What is the evolution path of brand-oriented research?

- RQ4: What are the research limitations of the existing research and what are the future research directions?

Therefore, the primary contributions of this study can be summarized as follows. First of all, scientific knowledge mapping as a new method of scientometrics is introduced into the field of brand orientation, which objectively and quantitatively displays the distribution of brand orientation research and important knowledge bases through bibliometric analysis. Secondly, comprehensively using keyword co-occurrence analysis and the traditional literature review method, this study demonstrates and discusses six research clusters, and their hot areas in the field of brand orientation are demonstrated and discussed, including conceptualization and operationalization of brand orientation construct, connections and distinctions between brand orientation and market orientation, the effects of brand orientation on organizational performance, relationship between brand orientation and internal branding, relationship between brand orientation and customer, as well as determinants of brand orientation. Thirdly, this study constructs the framework for the knowledge evolution of brand orientation and sorts out the research progress in the field of brand orientation in a systematic and multi-leveled manner for the first time, which provides useful references for future brand-oriented research.

The rest of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the methodology and data used to analyze the existing research in brand-oriented areas. In Section 3, we utilize the method of scientific knowledge mapping to demonstrate knowledge bases in the brand-oriented field and build the framework for knowledge evolution of brand orientation. Section 4 discusses the research hot spots regarding brand orientation. Section 5 summarizes the findings and proposes the research limitations and the direction of future brand-oriented research.

2. Methodology

2.1. Analytic Technique

This research combines the bibliometrics methods based on scientific knowledge mapping with the traditional literature review analysis to conduct data mining, information processing, and knowledge measurement on the literature resources in the brand-oriented field. First, this study uses the CiteSpace5.6.R2 software to conduct the co-citation analysis of brand-oriented research results and measures the correlation strength of literature to demonstrate the knowledge bases and evolution in the field of brand orientation. In addition, a co-occurrence network for keywords is established through the keyword co-occurrence analysis to identify research hot spots in the field of brand orientation. Finally, this study uses the traditional literature review method to integrate fragmented research and systematically summarizes the knowledge system in the brand-oriented field.

2.2. Data Sources

Given that WOS is considered to be the oldest [41], most commonly used, and most reliable database of academic papers and citations in the world [42], this study chose Clarivate’s Web of Science (WOS) database to retrieve data for bibliometric analysis information [43,44]. Furthermore, WOS was the first bibliographic database, established in the 1960s, and is considered the “gold standard” for bibliographic analysis compared to other newer databases such as Scopus or Google Scholar, both of which were launched in 2004 [45].

The literature source is “Web of Science” (hereinafter referred to as WOS), including six citation database such as SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSHESCI, ESCI. The search rule is “TS = (“brand-orientation”) OR TS = (“brand-oriented”) OR TS = (“brand-orientated”)”. The literature type is “Article, Proceeding paper, Review”. Since the concept of brand orientation was first proposed by Urde in 1994, the time span of literature retrieval process is set as 1990–2021. A total of 169 literatures (literature time span is 2005–2021) were retrieved, and 7187 references were fully recorded and cited. This paper uses these data to establish the original database for the study, importing the original data into the CiteSpace5.6.R2 software for data deduplication, and set the Time Slicing to 2005–2021 and the Year Per Slice to 1. The search details are summarized as in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of search details.

3. Results

3.1. Journal, Country or Region Distribution of the Publications

It can be seen from Table 2 that the top five journals with the largest number of publications accounted for a total of 26.63%, and the focus on this topic also mainly came from the fields of brand management and marketing in business research. This indicates that the distribution of journals published in brand-oriented literature is relatively scattered, and brand-oriented research is still in the exploratory stage.

Table 2.

Journal distribution of the publications.

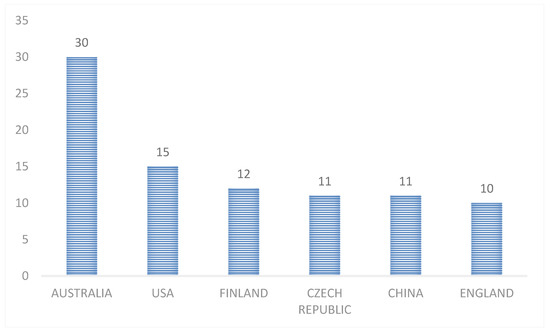

The number of publications can reflect the research level and field contribution of different countries or regions and scientific research institutions to a certain extent. As can be seen from Figure 1, the top 6 countries/regions with the number of published brand-oriented research results are: Australia (30), the United States (15), Finland (12), the Czech Republic (11), China (11), and the United Kingdom (10).

Figure 1.

Country or region distribution of the publications.

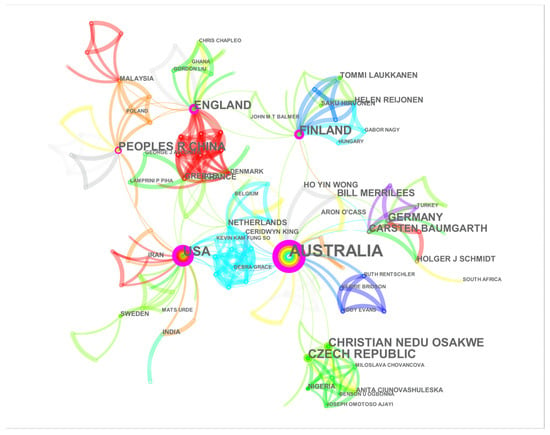

In the CiteSpace5.6.R2 software, set the node type of the network attribute to Author and Country to obtain the brand-oriented research document “Author-Country Cooperation Network”, as shown in Figure 2. According to the betweenness centrality, nodes with values over 0.1 are called key nodes. Obviously, the research in the field of brand orientation has formed 5 key nodes, with Australia (0.67), the United States (0.46), the United Kingdom (0.27), Finland (0.23), and China (0.19) as the core.

Figure 2.

Network map of country or region distribution of literature.

3.2. Literature Co-Citation Analysis

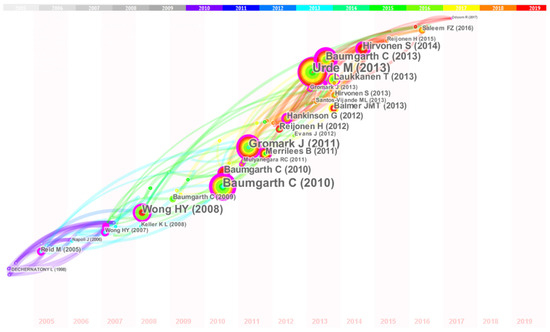

The research selects the network node as “Reference”, the data screening strategy as Top 100, and the network pruning method as the pathfinding algorithm by using the CiteSpace method to analyze the co-citation relationship of 7187 references from 2005 to 2021. The co-citation time zone network of the literature (e.g., Figure 3) and the bibliography of important nodes (e.g., Table 3) are obtained. The nodes in the figure represent the analyzed references. The higher the citation frequency, the larger the nodes will be, indicating that they are important knowledge bases in this field. Higher centrality of the node means that it forms co-citation relationships with multiple literatures, which plays a “hub” role, representing the key literature in this field. The links between nodes indicate the co-citation relationship, and the thickness represents the co-citation strength. Therefore, combined with the co-citation time zone network and the literature with high citation and high centrality, this research determines key research results in the field of brand orientation, laying a foundation for the future research of brand orientation.

Figure 3.

Co-citation time zone network of literature.

Table 3.

Bibliography of important nodes.

According to Figure 3, one of the foundational literatures of brand-oriented research since 2005 is published by Reid et al. [46]. This literature systematically explains the differences and relationships among brand orientation, market orientation, and integrated marketing communication for the first time, providing a research paradigm for the follow-up discussion on how brand orientation affects organizational performance through external channels such as market orientation and integrated marketing communication. Subsequently, research on brand orientation has gradually extended to many industries, including non-profit organizations, retailing, service, manufacturing, tourism, and public sectors, enriching the research results of brand orientation in specific situations [8,11,13,21,25,47]. For example, Napoli [26] developed the non-profit brand orientation scale based on the brand record card, which provides a basis for the quantitative research on the brand orientation of non-profit organizations. Wong and Merrilees [15,18] analyzed the interaction among marketing activities, innovation activities, and the brand orientation of retailing, service, and manufacturing enterprises, as well as the hindering effect of the resource scarcity on brand orientation, which provides empirical evidence and practical ideas for organizations to give play to the effectiveness of brand orientation in management practices and marketing activities.

Since 2013, brand-oriented literature has gradually increased. The most cited literature published by Urde et al. [7], has transferred the academic debate between brand orientation and market orientation from the “either this or that” tug of war and discussed the synergy and evolution of brand orientation and market orientation in the process of the enterprise development from the perspective of dynamic development. This study proposed two novel strategic hybrid orientation modes including “brand and market orientation” and “market and brand orientation”, which expanded the scope of enterprises from brand orientation or market orientation to other strategic choices, providing a new mode of thinking for the research of brand orientation. The above literature (e.g., Table 3) is a significant node of brand-oriented research literature, which further promotes the development of brand-oriented research.

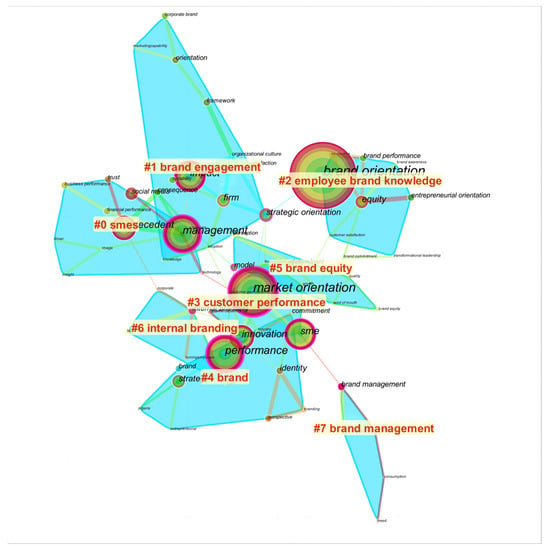

3.3. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

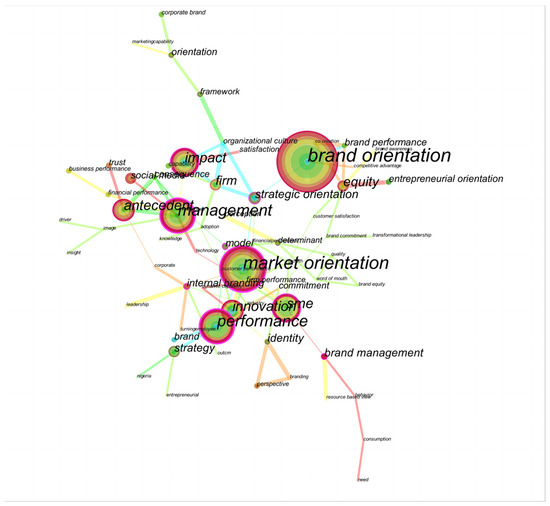

This paper selects the network node as “Keyword”, the data screening strategy as Top 100, and the network pruning method as the pathfinding algorithm by using the CiteSpace5.6.R2 software to conduct the keyword co-occurrence analysis. The keyword co-occurrence of 169 literatures from 2005 to 2021 is analyzed, and the visualization of the keyword co-occurrence (e.g., Figure 4) and keyword clusters (e.g., Figure 5) is displayed. There are 71 nodes and 174 connecting lines in the mapping. The modularity value, i.e., Q value, is 0.6742 (greater than 0.3), and the silhouette value, i.e., S value, is 0.8112 (greater than 0.7), indicating that the mapping structure is significant and the results are valid. In Table 4, the keywords in the brand-oriented field are presented according to the keyword co-occurrence frequency. The co-occurrence frequency of keywords more than 20 times includes “brand orientation (63 times)”, “market orientation (47 times)”, “management (33 times)”, “performance (30 times)”, “impact (20 times)”, and “antecedent (20 times)”, whereas the co-occurrence frequency of other keywords is less than 20 times. It can be seen that the 169 brand-oriented articles involve various research contents and scattered concerns, which are still in the initial exploration stage.

Figure 4.

Visualization of keyword co-occurrence analysis.

Figure 5.

Visualization of keyword cluster analysis.

Table 4.

Summary of keywords on brand orientation.

A total of 169 literatures are automatically divided into 10 clusters through the cluster analysis of keywords, excluding 2 minor clusters, and finally 8 clusters are obtained (e.g., Figure 5). The name of the cluster is extracted from the keywords of 169 literatures, which fail to fully represent the characteristics of the cluster [48], and there is knowledge overlap to some degree. For example, the CiteSpace5.6.R2 software named Cluster 0 as “SME”, which mainly involves the brand-oriented research of SMEs, and named Cluster 4, Cluster 5, and Cluster 7 as “brand”, “brand equity”, and “brand management”, respectively. Through the analysis of literature, it is proved that the research on brand orientation of SMEs involves brand, brand equity, and brand management, meaning that there is a serious overlap of knowledge, which may be due to the fact that the research in this field is still in the exploratory stage and the amount of literature is relatively small. Therefore, the keyword clustering results using the CiteSpace5.6.R2 software fail to clearly show the research hot spots in the field of brand orientation and are required to be combined with the traditional literature review method for the further research.

In view of this, combined with the traditional literature review method, this study summarizes six research hot spots in the current brand-oriented field by interpreting the keyword co-occurrence frequency, centrality of nodes, nodes, and links in the visualization of keyword co-occurrence (e.g., Figure 4). The first and second research hot spots are at the center of the keyword co-occurrence network, including “brand orientation” and “market orientation”, which are respectively about the development and measurement of the brand orientation theory and the relationships between brand orientation and market orientation; the third research hot spot is around the first and second research hot spots, which discusses the relationships between brand orientation and organizational performance, including keywords such as “performance”, “impact”, “firm performance”, “brand performance”, “business performance”, “financial performance”, and “growth”. The fourth and fifth research hot spots are distributed at the edge of the keyword co-occurrence network, which are, respectively, with respect to the relationships between brand orientation and internal brand building, including keywords such as “internal branding”, “employee”, “transformational leadership”, “corporate brand”, “brand commitment”, “brand equity”, and “brand awareness”. They also discuss the research on the relationships between brand orientation and customers, including keywords such as “trust”, “satisfaction”, “customer performance”, “brand buying behavior”, “consumption”, and “word of mouth”. In addition, in the upper left corner of the keyword co-occurrence network, the co-occurrence frequency (20) and the centrality (0.17) of the keyword “antecedent” are both high. The related keywords including “driver” and “decisive” constitute the sixth research hot spot—namely, the influencing factors of brand orientation.

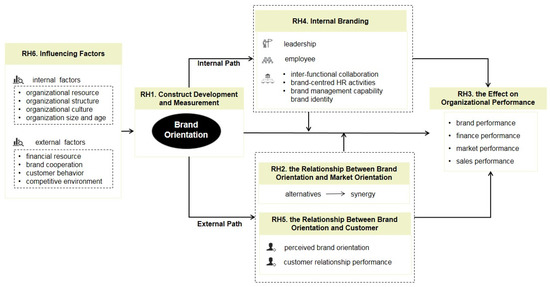

3.4. Analysis of Brand-Oriented Knowledge Evolution

This study constructs an overall framework for brand-oriented knowledge evolution, as shown in Figure 6, based on the co-citation analysis of literature, keyword co-occurrence analysis, and traditional literature review analysis. First, the research of brand orientation is rooted in marketing theory, brand management theory, strategic management theory, and a resource-based view of the firm. Since then, based on the industry characteristics and brand management characteristics of specific situations, scholars have extended the brand-oriented research to fields including non-profit organizations, retail, service, manufacturing, e-commerce, and tourism. In combination with corporate culture theory, consumer behavior theory, leadership theory, upper-echelon theory, human resource management theory, and performance management theory, the research contents of brand orientation have been constantly furthered, concentrating on the core issue of “whether and how brand orientation becomes an effective strategic orientation of an organization”. Up to now, the research contents of brand orientation tend to be concluded by 6 major research hot spots, including conceptualization and operationalization of brand orientation construct, connections and distinctions between brand orientation and market orientation, the effects of brand orientation on organizational performance, the relationship between brand orientation and internal branding, the relationship between brand orientation and customer, as well as researches on influencing factors that drive or hinder brand orientation.

Figure 6.

The framework of brand-oriented knowledge evolution.

4. Discussion

4.1. Conceptualization and Operationalization of Brand Orientation

Urde first proposed the concept of “brand orientation”, which was defined as a method for an organization to continuously interact with target customers in the process of creating, developing, and protecting brand identity in order to achieve lasting competitive advantages in the form of brands. Urde conceptualized brand orientation into a seven-dimensional paradigm including products, trademarks, positioning, enterprise names, enterprise identity, target groups, and brand vision, and further pointed out that the value-added process of an enterprise is the result of the interaction of the above seven dimensions, among which brand vision is the strategic essence of brand-oriented enterprises [2,3].

Subsequently, scholars defined brand orientation from different perspectives based on various research purposes and discussed the development and measurement of brand orientation in specific situations. Current researches tend to utilize either a philosophical or a behavioral approach to brand orientation [49], among which the philosophical view contends that brand orientation should be embedded in the organization thinking and reflected in the value and concepts of organizations. For example, some scholars defined brand orientation based on the recognition of brand importance [12,16], brand capabilities [9,17], corporate culture [8,13] and the mode of thinking or concept system [11,14,15]. The behavioral view emphasized the orientation of behavior and activities, focusing on organizational processes [10], organizational practices, and behaviors [9,13]. On the basis of concept definition, scholars also creatively put forward the construct measurement models of brand orientation based on the specific situations, which are suitable for fields including non-profit organizations [10], retail [15], manufacturing [2,3], and overall perspective [11] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Conceptualization and operationalization of brand orientation.

Above all, brand orientation is conceptualized as a multi-dimensional structure, covering the values, beliefs, behavior, and practices of organizations. Although scholars have not reached an agreement on the concept definition and construct measurement of brand orientation, the existing definitions of brand orientation are rooted in the traditional brand concept, covering the elements of the marketing theory and the resource-based view of the firm.

4.2. Brand Orientation and Market Orientation

The discussion on the differences between brand orientation and market orientation is related to the way organizations treat brands and markets in essence [7]. Market orientation focuses on the product brand and regards meeting customer needs and establishing customer satisfaction and loyalty as the basic targets, which is a strategic and outside-in orientation driven by the brand image. By contrast, brand orientation concentrates on the organizational brand and regards maximizing the brand equity as the guidance, which is a strategic and inside-out orientation driven by the brand identity [3,7]. Therefore, brand orientation is also considered as the internal orientation, whereas market orientation is regarded as the external orientation [51]. Compared with market orientation, brand orientation is different in that it takes the philosophical foundation such as the core value, vision, and mission of the organization as the cornerstone [3] from an extended stakeholder perspective [47], rather than only focusing on meeting customer needs. Brand orientation emphasizes broader organizational goals instead of viewing profits as the only goal, such as the role that the organization plays in the social environment. Therefore, brand orientation diminishes the risk of short-sightedness and the reactivity of market orientation due to the excessive focus on customers and emphasis on external perspectives. For a brand-oriented organization, balancing the interests of different stakeholders against its organizational mission, vision, and core values is fundamental [47].

However, brand orientation and market orientation are interrelated [52]. The most common argument is that brand orientation is on the basis of market orientation [2,3]. The more people perceive that an organization is market-oriented, the more they believe that the organization is brand-oriented [53,54]. Another point views brand orientation and market orientation as a dynamic interaction and synergy, resulting in two different types of the strategic hybrid orientation, namely “market and brand orientation” and “brand and market orientation” [7,55]. Urde [7] emphasized that the strategic hybrid orientation is more realistic and effective for theoretical development and business practice, due to the fact that the competitive business environment may reduce the direct performance of the single orientation, whereas the two complement each other to achieve synergy [31,51,56].

4.3. Brand Orientation and Organizational Performance

Empirical research on the impacts of brand orientation on organizational performance can be divided into direct effect tests and indirect effect tests, among which direct effect tests concentrate on exploring the influence of various dimensions of brand-oriented constructs on organizational performance [11,25,27,57]. Other studies have further explored internal factors, such as enterprise ages [58], enterprise scale [32], innovation capabilities [59], brand standardization [60], and external factors, such as customer types [58], industry types [32], social media [59], and the moderating effects of customer orientation and relationship marketing orientation [61] on the direct effects between brand orientation and organizational performance. The indirect effect tests mainly discuss the mechanism of brand orientation on organizational performance from three perspectives. The first is to discuss factors that exert a mediating effect on brand orientation and organizational performance from an internal perspective, such as internal branding [30], strategic brand management [62], brand management capabilities [63], brand identity [30,64], brand uniqueness [15], transformational leadership and cross-function departmental integration [31], learning orientation [65], and COVID-19 [66]. The second is to discuss factors that exert a mediating effect on brand orientation and organizational performance from an external perspective, such as market orientation [51], integrated marketing communication [46], positional advantages [49], and customer value co-creation [33,67]. Thirdly, from an overall perspective, it expounds how brand orientation acts on organizational performance through integrated approaches internally and externally [68]. For example, Anees-ur-Rehman [69] pointed out that brand orientation can improve brand awareness through brand communication (external approach) and enhance brand reputation through internal branding (internal approach), thus improving team financing performance.

Although a large number of empirical studies have verified the positive impact of brand orientation on organizational performance [15,19,25], research on the relationship between brand orientation and organizational performance is still controversial [30,31]. For example, research on B2B SMEs by Hirvonen [32] proved that brand orientation has no significant direct impact on brand performance and exerted a weak influence on business growth. This is different from the assertion that “brand orientation has a significant positive impact on the market performance and financial performance of B2B enterprises” [13]. In addition, brand orientation as a strategic choice has different effects on enterprises with different years, scales, fields, and brand knowledge levels [32,58] and is also different for enterprises in different market life cycles [19]. Therefore, it is necessary for organizations to combine brand orientation with other management strategies to form strategic complementation instead of following a single brand orientation [70].

4.4. Brand Orientation and Internal Branding

Internal branding is considered as a method to create a strong enterprise brand, which can help organizations align their internal processes and organizational culture with the brand [71]. Current research mainly discusses how to influence the attitude and behavior of internal personnel through internal branding in order to fulfil consistent brand commitments, provide consistent brand behavior, ensure the brand experience and brand value of customers, and finally realize the appreciation of brand equity. It mainly emphasizes the core role of internal employees, the key role of senior managers, the necessity of cross-functional cooperation, and brand-centered HR activities.

Internal branding has proved to be an effective tool to ensure brand-oriented behavior of employees. [22,24]. For example, Baumgarth and Schmidt [21] found that brand-oriented culture significantly affects internal brand knowledge, internal brand commitment, and internal brand involvement of employees. The point was to ensure that employees translated the brand information convinced by customers into the “brand reality” of customers and other stakeholders in the external market [72]. Some scholars have studied the interaction between brand orientation and employee attitude or behavior, indicating that brand orientation, job satisfaction, and internal branding all have positive effects on one other [29,73]. Therefore, organizations can improve the internalization of the organizational brand among employees by internal branding construction.

In addition, brand orientation also has a positive effect on the attitude and behavior of senior managers. For example, Dludla and Dlamini [74] proved that brand orientation has a significant positive impact on the brand commitment and brand trust of senior managers, whereas the brand commitment and brand trust have significant positive correlation with the brand loyalty. In turn, the strong leadership of senior managers plays a crucial role in shaping brand orientation of enterprises [25]. For example, senior managers play a transformative role in repositioning the organization to be identity-oriented in order to promote communication among internal and external stakeholders [75,76]. It is worth noting that transformational leadership fails to significantly adjust the impact of brand orientation on enterprise performance. Only when transformational leadership, cross-function departmental integration, and brand-oriented work together, the relationship between brand orientation and enterprise performance will be strengthened [31].

4.5. Brand Orientation and Customer

The research on brand orientation and customer relationship is mainly divided into two perspectives. One is the research on perceived brand orientation and customer relationship (attitude or behavior). The other is the research on brand orientation and customer relationship performance based on enterprise self-evaluation, such as customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, acquiring new customers, etc.

As the evolution of brand orientation concept from the customer perspective, perceived brand orientation was first proposed by Mulyanegara [54]. On the basis of non-profit brand orientation, it is conceptualized as three themes, including uniqueness, reputation, and orchestration, aiming to measure the attitude of customers towards brand-oriented activities of the organization. At present, the research on perceived brand orientation and customer relationships based on the customer survey mainly involves non-profit fields such as the church [77,78] and higher education [79]. For example, Ghobehei et al. [80] verified the positive effect of perceived brand orientation on service quality, trust, satisfaction, loyalty, and word-of-mouth behavior of colleges and universities from the perspective of students and further proved that perceived brand orientation significantly moderates the quality and loyalty of perceived service.

Research on SMEs in the context of developing economies demonstrated that there is positive correlation between brand orientation and customer relationship performance [63]. It is emphasized that SMEs should regard brand orientation as a comprehensive strategy across the whole enterprise value chain instead of an isolated strategy. For example, Chovancova et al. proved the positive effect of brand orientation on customer relationships for small service enterprises in Nigeria [81]. However, Hirvonen [32] failed to prove that brand orientation has significant direct correlation with customer relationship performance based on the study of Finnish B2B SMEs. One possible reason is that the purchase decision of customers in the industrial market is mainly affected by the product performance and quality. Although emotional brand qualities are also concerned by B2B customers, their primary role is to reduce perceived risk and provide guarantee.

4.6. Determinants of Brand Orientation

The determinants of brand orientation include external factors and internal factors (Table 6). The studies of external factors shows that an environment of competition [2], funding sources [82], brand cooperation [83], partners [84], and customer behavior [12] are critical factors of brand orientation. For example, research of national museums in the UK, the United States, and Australia indicated that intensified direct competition from peers, indirect competition from other leisure industries (such as tourism), and changes in behavior of tourists all force museums to adopt brand-oriented strategies and seek new competitive advantages [82].

Table 6.

Determinants of brand orientation.

The studies of internal factors have conducted in-depth analysis from the organizational level and the leadership level. At the organizational level, scholars mainly analyzed the impact of organizational resources [15,33], organizational structure [34], organizational culture [85], and organizational scale and age [82] on brand orientation. For example, the empirical results of 569 manufacturing enterprises in Taiwan from the perspective of organizational environment showed that organizational resources (product differentiation capability), organizational structure (cross-function departmental integration), and organizational culture (members’ organizational identification and long-term remuneration criteria) could facilitate the building of brand-oriented companies [34]. It is worth mentioning that a large number of studies have emphasized that the investment of organizational resources, such as money, time, and manpower, is the foundation for the strategic development of brand orientation [15,82], whereas SMEs are considered difficult to implement brand-oriented strategies due to limited resources. Therefore, Cardinali [83] proposed that SMEs could overcome the resource scarcity barrier by obtaining brand licensing, improved brand capabilities, and brand orientation with a brand portfolio composed of both owned and licensed brands. Huang and Tsai [34] indicated that low-cost marketing and communication means (such as public communication, word-of-mouth communication, and network communication) could also be used to create brand identity and brand image, especially for SMEs.

In addition, there are some obstacles at the organizational level, such as the complexity of the organizational structure—the huge system caused by the large scale or the long service life of the organization—and historical problems, that all have negative impacts on brand orientation [82]. Additionally, a non-commercial mindset, short-term focus, communication challenges, organizational culture, government barriers, and a lack of resources can all hinder the implementation of a brand-led strategy [84]. Therefore, adventurous and strong leaders are required to prioritize the allocation of resources for the development of brand-supporting capabilities [85] and to promote brand-oriented development.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Findings

This study discusses the co-citation analysis of literature, keyword co-occurrence analysis, and research hot spots of 169 literatures and 7187 references in the field of brand orientation by comprehensively using the methods of bibliometrics and traditional literature review with the CiteSpace5.6.R2 software, and it constructs an overall framework for brand-oriented knowledge evolution, as shown in Figure 6. The main findings are as follows:

First, brand-oriented researches have increased significantly since 2013, but the overall number is small and still in the initial stage of exploration. The distribution of the journals of the published literature is also relatively scattered, but the published fields are relatively concentrated. The core publications are from the field of brand management and marketing in the field of business research, including: Journal of Brand Management; European Journal of Marketing; Journal of Business Research; Journal of Product and Brand Management; Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing.

Second, the research in the field of brand orientation has formed five core areas centered on Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Finland, and China. Among them, Australia (30) leads the world in terms of the number of publications, followed by the United States (15). China (11) published relatively few papers, and its betweenness centrality was relatively low (0.19).

Third, one of the foundational literatures of brand-oriented research since 2005 is published by Reid [46]. This literature systematically explains the differences and relationships among brand orientation, market orientation, and integrated marketing communication for the first time, providing a research paradigm for the follow-up researches. The most cited literature is published by Urde, which discusses the synergy and evolution of brand orientation and market orientation and puts forward two novel strategic hybrid orientation modes, including “brand and market orientation” and “market and brand orientation”. In spite of this, the research results regarding brand orientation are relatively few, involving various research contents and scattered concerns, which are still in the initial exploration stage. Specifically, the keyword co-occurrence analysis of 169 literatures demonstrates that the keywords with a co-occurrence frequency of more than 20 times includes “brand orientation (63 times)”, “market orientation (47 times)”, “management (33 times)”, “performance (30 times)”, “impact (20 times)”, and “antecedent (20 times)”, whereas the co-occurrence frequency of other keywords is less than 20 times.

Forth, the research of brand orientation is rooted in the marketing theory, brand management theory, strategic management theory, and resource-based view of the firm. Since then, based on the industry characteristics and brand management characteristics of specific situations, scholars have extended the brand-oriented research to the fields, including non-profit organizations, charities, museums, retail, tourism, higher education, SMEs, and B2B. In combination with corporate culture theory, consumer behavior theory, leadership theory, upper-echelon theory, human resource management theory, and performance management theory, the research contents of brand orientation have been constantly furthered. Up to now, the research areas of brand orientation tend to be concluded to 6 major research hot spots, including conceptualization and operationalization of brand orientation construct, connections and distinctions between brand orientation and market orientation, the effects of brand orientation on organizational performance, the relationship between brand orientation and internal branding, the relationship between brand orientation and customer, as well as determinants of brand orientation.

5.2. Limitations

Inevitably, there are some limitations in this study. In view of the status and importance of the WOS database, the data source of this study focuses on the scientific literature retrieved from the WOS database. Although, this study also summarizes the content of some scientific literatures in the Scopus database [36,37,58,86,87,88] in the way of traditional literature review. However, the bibliometric analysis using Citespace software does not involve Scopus database, CNKI database, and other database information. Therefore, using other databases may yield slightly different results.

The goal of this study is to provide a more comprehensive and systematic review of the scientific literature in the field of brand orientation. Therefore, the research status, progress, and evolution of brand orientation in specific fields such as B2B, SME, and NPO have not been presented, which is another limitation of this study. For example, the research results of brand orientation in the B2B field are covered in the analysis of hot spots such as brand orientation construct, brand orientation, and organizational performance. However, this study does not present the bibliometric analysis results of brand-oriented literature in the B2B field, such as research distribution, knowledge base, and evolutionary path. Therefore, a scientometric analysis of the brand-oriented literature in specific domains, such as B2B, SME, NOP, etc., may yield different results.

5.3. Future Research Directions

From an academic point of view, the topic of brand orientation is one of many multilayered topics in many related fields. Actually, this vast amount of information from different research topics provides the analytical basis for scientific research. In these cases, future research should continue to investigate bibliometric analysis and literature review analysis in specific fields such as B2B, SME, NPO, charitable organizations, higher education, tourism, etc. Future research should also continue to investigate the relationship between brand orientation and other concepts such as corporate social responsibility, business ethics, and sustainable leadership to identify new innovative research directions [43].

In addition, brand management should also keep pace with the times in the era of digital economy. Enterprises can use various forms of digital media such as TikTok and Weibo to conduct digital marketing, deepen users’ understanding of the brand, and deeply interact with users, so as to shape the corporate image in the minds of consumers and improve brand value and organizational performance. The future studies are required to be further promoted and discussed in the network economy age, such as broadening the concept of “online brand orientation”, exploring how traditional organizations utilize online channels to conduct brand orientation, and analyzing the influencing factors of how electronic commerce enterprises conduct brand orientation. It is necessary for future research to note that the changes brought about by the network economy era are multifaceted, such as online shopping behavior of customers, online communication of employees and customers, information flooding, and live-streaming e-commerce.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.; Methodology, S.L. and L.W.; Software, L.W.; Validation, Y.S. and L.W.; Formal analysis, S.L. and Y.S.; Investigation, Y.S.; Writing—original draft, S.L.; Writing—review & editing, S.L. and Y.S.; Visualization, S.L. and L.W.; Project administration, E.X.; Funding acquisition, E.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, funding number 7217020877, and Beijing Institute of Technology, funding number 2021ZXJG013.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Wang, Y.; Xie, C.Y. New Challenges of Business Management in Digital Economy—Marketing Management. Available online: https://cj.sina.com.cn/articles/view/7395349859/1b8cc15630190103qm (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Urde, M. Brand orientation—A strategy for survival. J. Consum. Mark. 1994, 11, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urde, M. Brand orientation: A mindset for building brands into strategic resources. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R.T.; Ambler, T.; Carpenter, G.S.; Kumar, V.; Srivastava, R.K. Measuring marketing productivity: Current knowledge and future directions. J. Mark. 2018, 68, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyrd-Jones, R.I.; Helm, C.; Munk, J. Exploring the impact of silos in achieving brand orientation. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 1056–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarth, C.; Merrilees, B.; Urde, M. Brand orientation: Past, present, and future. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urde, M.; Baumgarth, C.; Merrilees, B. Brand orientation and market orientation—From alternatives to synergy. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarth, C. Brand orientation of museums: Model and empirical Results. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2009, 11, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bridson, K.; Evans, J. The secret to a fashion advantage is brand orientation. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2004, 32, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, M.T.; Napoli, J. Developing and validating a multidimensional nonprofit brand orientation scale. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromark, J.; Melin, F. The underlying dimensions of brand orientation and its impact on financial performance. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 18, 394–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankinson, P. Brand orientation in the charity sector: A framework for discussion and research. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2001, 6, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T.C.; Baumgarth, C. “Living the brand”: Brand orientation in the business-to-business sector. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, J.; Wong, H.Y.; Merrilees, B. Multiple roles for branding in international marketing. Int. Mark. Rev. 2007, 24, 384–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.Y.; Merrilees, B. The performance benefits of being brand-orientated. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008, 17, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankinson, P. The impact of brand orientation on managerial practice: A quantitative study of the UK’s top 500 fundraising managers. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2002, 7, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridson, K.; Mavondo, F. Brand orientation: Conceptualisation, operationalisation and explanatory power. In Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference, Geelong, Australia, 1 January 2002; pp. 2151–2158. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, H.Y.; Merrilees, B. Closing the marketing strategy to performance gap: The role of brand orientation. J. Strateg. Mark. 2007, 15, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijonen, H.; Laukkanen, T.; Komppula, R.; Tuominen, S. Are growing SMEs more market-oriented and brand-oriented? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2012, 50, 699–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.Y.; Merrilees, B. A Brand Orientation Typology for SMEs: A Case Research Approach. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarth, C.; Schmidt, M. How strong is the business-to-business brand in the workforce? An empirically-tested model of ‘internal brand equity’ in a business-to-business setting. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, J.; Kerr, G.; Clarke, R.J. Brand orientation and the voices from within. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 1079–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’zungu, S.D.M.; Merrilees, B.; Miller, D. Brand management to protect brand equity: A conceptual model. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjaisri, K.; Evanschitzky, H.; Wilson, A. Internal branding: An enabler of employees’ brand-supporting behaviours. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2009, 20, 209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson, G. The measurement of brand orientation, its performance impact, and the role of leadership in the context of destination branding: An exploratory study. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 974–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, J. The impact of nonprofit brand orientation on organisational performance. J. Mark. Manag. 2006, 22, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.J.; Mason, R.; Steenkamp, P. Does brand orientation contribute to retailers’ success? An empirical study in the South African market. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoom, R. Brand Marketing Programs and Consumer Loyalty—Evidence from Mobile Phone Users in an Emerging Market. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Ghytasivand, F.; Fakharmanesh, S. Impact of brand orientation, internal marketing and job satisfaction on the internal brand equity: The case of Iranian’s food and pharmaceutical companies. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2012, 2, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen, S.; Laukkanen, T. Brand orientation in small firms: An empirical test of the impact on brand performance. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boso, N.; Carter, P.S.; Annan, J. When is brand orientation a useful strategic posture? J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, S.; Laukkanen, T.; Salo, J. Does brand orientation help B2B SMEs in gaining business growth? J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Arnett, D.B. Enhancing firm performance: The role of brand orientation in business-to-business marketing. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 72, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.T.; Tsai, Y.T. Antecedents and consequences of brand-oriented companies. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 2020–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabowski, B.R.; Samiee, S.; Hult, G. A bibliometric analysis of the global branding literature and a research agenda. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2013, 44, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J. Corporate brand orientation: What is it? What of it? J. Brand Manag. 2013, 20, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anees-ur-Rehman, M.; Wong, H.Y.; Hossain, M. The progression of brand orientation literature in twenty years: A systematic literature review. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 612–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulcri, L.M.C.B.; Mainardes, E.W.; Marchiori, D.M. Brand orientation: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Span. J. Mark.—ESIC 2020, 24, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. Citation Space Analysis Principles and Applications: CiteSpace Practical Guide; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, C.M. CiteSpace: Tech Text Mining and Visualization; Capital Economic and Trade University Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, M.P.; Rego, A.; Oliveira, P.; Rosado, P.; Habib, N. Product innovation in resource-poor environments: Three research streams. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkle, C.; Pendlebury, D.A.; Schnell, J.; Adams, J. Web of Science as a data source for research on scientific and scholarly activity. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.; Bugheanu, A.M.; Dinulescu, R.; Potcovaru, A.M.; Stefanescu, C.A.; Marin, I. Exploring the Research Regarding Frugal Innovation and Business Sustainability through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.V.; Dima, A.; Radu, E.; Dumitrache, V.M. Bibliometric Analysis of the Green Deal Policies in the Food Chain. Amfiteatru Econ. 2022, 24, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckute, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, M.; Luxton, S.; Mavondo, F. The relationship between integrated marketing communication, market orientation, and brand orientation. J. Advert. 2005, 34, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromark, J.; Melin, F. From market orientation to brand orientation in the public sector. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 1099–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.B.; Fu, Y.N. International research hotspots of innovation management and its evolution: Based on visual analysis. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2019, 41, 186–199. [Google Scholar]

- Bridson, K.; Evans, J.; Mavondo, F.; Minkiewicz, J. Retail brand orientation, positional advantage and organisational performance. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2013, 23, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piha, L.; Papadas, K.; Davvetas, V. Brand orientation: Conceptual extension, scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.T.; O’Cass, A.; Sok, P. How and when does the brand orientation-market orientation nexus matter? J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2020, 35, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdil, T.S.; Bakr, N.O.; Ayar, B. The impact of market and brand orientation on performance: An empirical study. In Proceedings of the ISMC 2017 13th International Strategic Management Conference, Podgorica, Serbia and Montenegro, 6–8 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen, T.; Tuominen, S.; Reijonen, H.; Hirvonen, S. Does market orientation pay off without brand orientation? A study of small business entrepreneurs. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyanegara, R.C. Market orientation and brand orientation from customer perspective an empirical examination in the non-profit sector. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’zungu, S.; Merrilees, B.; Miller, D. Strategic hybrid orientation between market orientation and brand orientation: Guiding principles. J. Strateg. Mark. 2017, 25, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anees-ur-Rehman, M.; Saraniemi, S.; Ulkuniemi, P.; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. The strategic hybrid orientation and brand performance of B2B SMEs. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2017, 24, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.C.; Mainardes, E.W.; Teixeira, A.M.C.; Júnior, L.C. Brand orientation of nonprofit organizations and its relationship with the attitude toward charity and donation intention. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2020, 17, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, S.; Laukkanen, T.; Reijonen, H. The brand orientation-performance relationship: An examination of moderation effects. J. Brand Manag. 2013, 20, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoom, R.; Mensah, P. Brand orientation and brand performance in SMEs: The moderating effects of social media and innovation capabilities. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.T.; O’Cass, A.; Sok, P. Unpacking brand management superiority: Examining the interplay of brand management capability, brand orientation and formalisation. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoom, R.; Tweneboah-Koduah, E.Y. Service brand orientation and firm performance: The moderating effects of relationship marketing orientation and customer orientation. In Academy of Marketing Science World Marketing Congress; Springer: Porto, Portugal, 2019; pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, P.; Davari, A.; Paswan, A. Determinants of brand performance: The role of internal branding. J. Brand Manag. 2018, 25, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciunova-Shuleska, A.; Osakwe, C.N.; Palamidovska-Sterjadovska, N. Complementary impact of capabilities and brand orientation on SMBs performance. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2016, 17, 1270–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.; Podnar, K. Corporate brand orientation: Identity, internal images, and corporate identification matters. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Bashir, T. The role of brand orientation in developing a learning culture and achieving performance goals in the third sector organizations. Int. J. Public Adm. 2020, 43, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucherov, D.G.; Tsybova, V.S.; Lisovskaia, A.Y.; Alkanova, O.N. Brand orientation, employer branding and internal branding: Do they effect on recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Bus. Res. 2022, 151, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Q. An empirical investigation between brand orientation and brand performance: Mediating and moderating role of value co-creation and innovative capabilities. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 967931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumasjan, A.; Kunze, F.; Bruch, H.; Welpe, I.M. Linking employer branding orientation and firm performance: Testing a dual mediation route of recruitment efficiency and positive affective climate. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 59, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anees-ur-Rehman, M.; Wong, H.Y.; Sultan, P.; Merrilees, B. How brand-oriented strategy affects the financial performance of B2B SMEs. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijonen, H.; Hirvonen, S.; Nagy, G.; Laukkanen, T.; Gabrielsson, M. The impact of entrepreneurial orientation on B2B branding and business growth in emerging markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 51, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punjaisri, K.; Wilson, A. The role of internal branding in the delivery of employee brand promise. Journal of Brand Management 2007, 15, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Shabbir, R.; Zhu, M. How brand orientation impacts B2B service brand equity? An empirical study among Chinese firms. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.; So, K.K.F.; Grace, D. The influence of service brand orientation on hotel employees’ attitude and behaviors in China. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dludla, G.M.; Dlamini, S. Does brand orientation lead to brand loyalty among senior and top management in a South African business-to-business organisation? S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmann, C.; Zeplin, S. Building brand commitment: A behavioural approach to internal brand management. J. Brand Manag. 2005, 12, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, C.; Chernatony, L.D. Internal brand building and structuration: The role of leadership. Eur. J. Mark. 2006, 40, 761–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyanegara, R.C. The relationship between market orientation, brand orientation and perceived benefits in the non-profit sector: A customer-perceived paradigm. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyanegara, R.C. The role of brand orientation in church participation: An empirical examination. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2011, 23, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casidy, R. Linking brand orientation with service quality, satisfaction, and positive word-of-mouth: Evidence from the higher education sector. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2014, 26, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobehei, M.; Sadeghvaziri, F.; Ebrahimi, E.; Bakeshloo, K.A. The effects of perceived brand orientation and perceived service quality in the higher education sector. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2019, 9, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chovancová, M.; Osakwe, C.N.; Ogbonna, B.U. Building strong customer relationships through brand orientation in small service firms: An empirical investigation. Croat. Econ. Surv. 2015, 17, 111–138. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Bridson, K.; Rentschler, R. Drivers, impediments and manifestations of brand orientation. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 1457–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, S.; Travaglini, M.; Giovannetti, M. Increasing brand orientation and brand capabilities using licensing: An opportunity for SMEs in international markets. J. Knowl. Econ. 2019, 10, 1808–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulcri, L.M.C.B.; Mainardes, E.W.; Pascuci, L. Non-profit Brand Orientation as a Strategic Communication Approach. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2022, 16, 572–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osakwe, C.N. Crafting an effective brand oriented strategic framework for growth-aspiring small businesses: A conceptual study. Qual. Rep. 2016, 21, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casidy, R. Brand Orientation and Service Quality in Online and Offl ine Environment: An Empirical Examination. In Let’s Get Engaged! Crossing the Threshold of Marketing’s Engagement Era; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; p. 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, S.; Laukkanen, T. The Moderating Effect of the Market Orientation Components on the Brand Orientation–Brand Performance Relationship. In Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science; Springer: Denver, CO, USA, 2016; pp. 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piha, L.P.; Avlonitis, G.J. Brand orientation: Antecedents and consequences. In Proceedings of the 2010 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference; Springer: Portland, OR, USA, 2015; p. 336. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).