Predictors of Upcycling in the Highly Industrialised West: A Survey across Three Continents of Australia, Europe, and North America

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Upcycling and Circular Economy

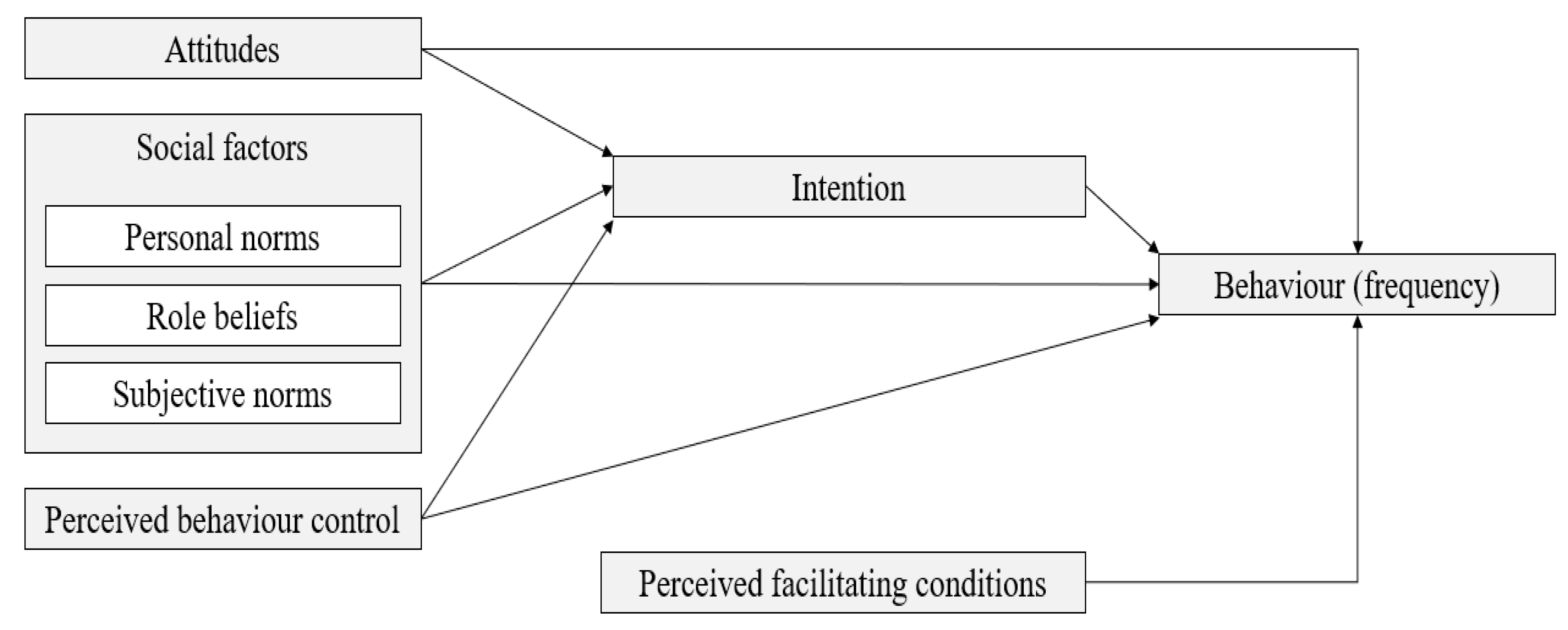

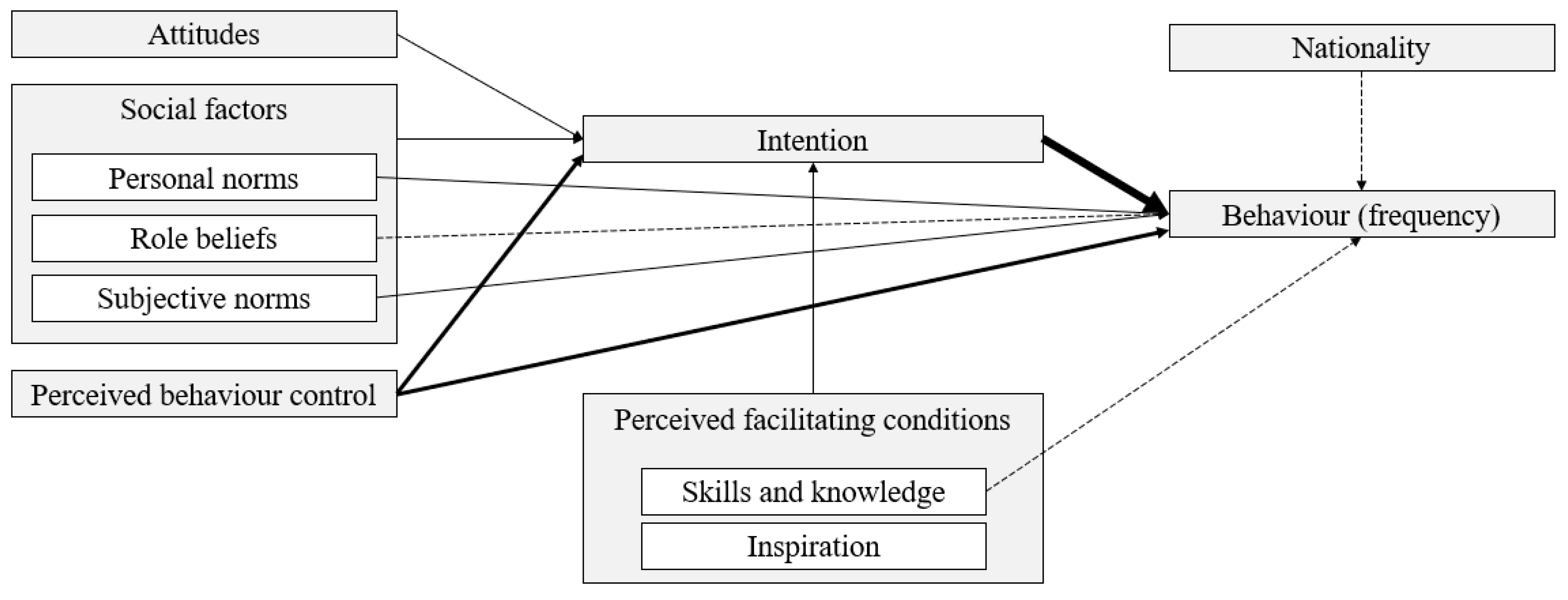

1.2. The Theory of Interpersonal Behaviour and Planned Behaviour

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and Research Instrument

2.2. Respondents

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Trends in Data

3.2. Group Differences in Upcycling Behaviour

3.3. Explaining Predictors of Upcycling Intention and Behaviour

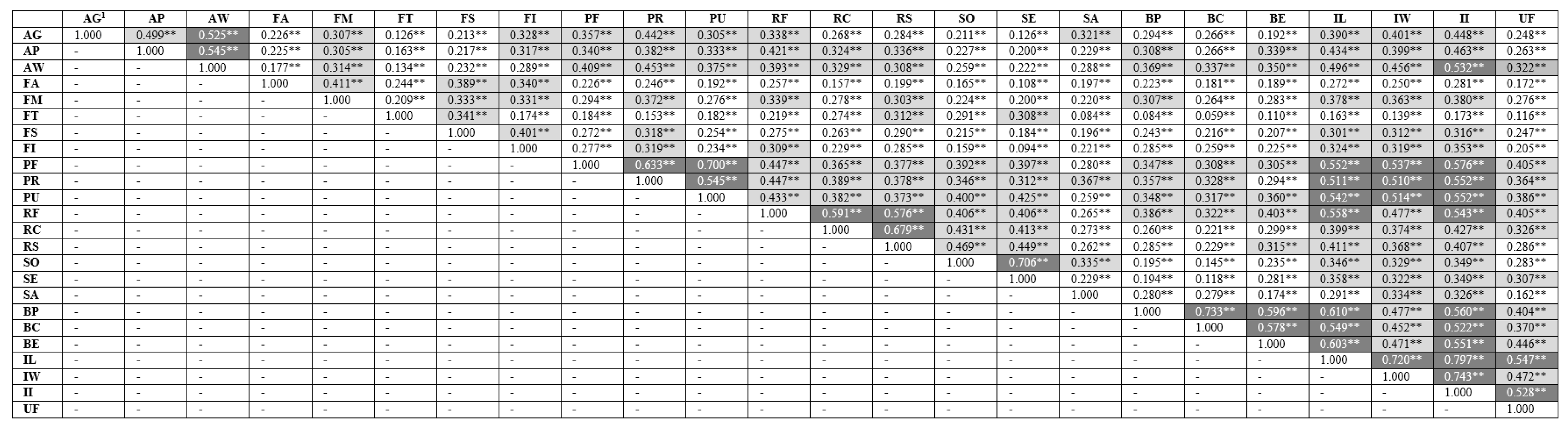

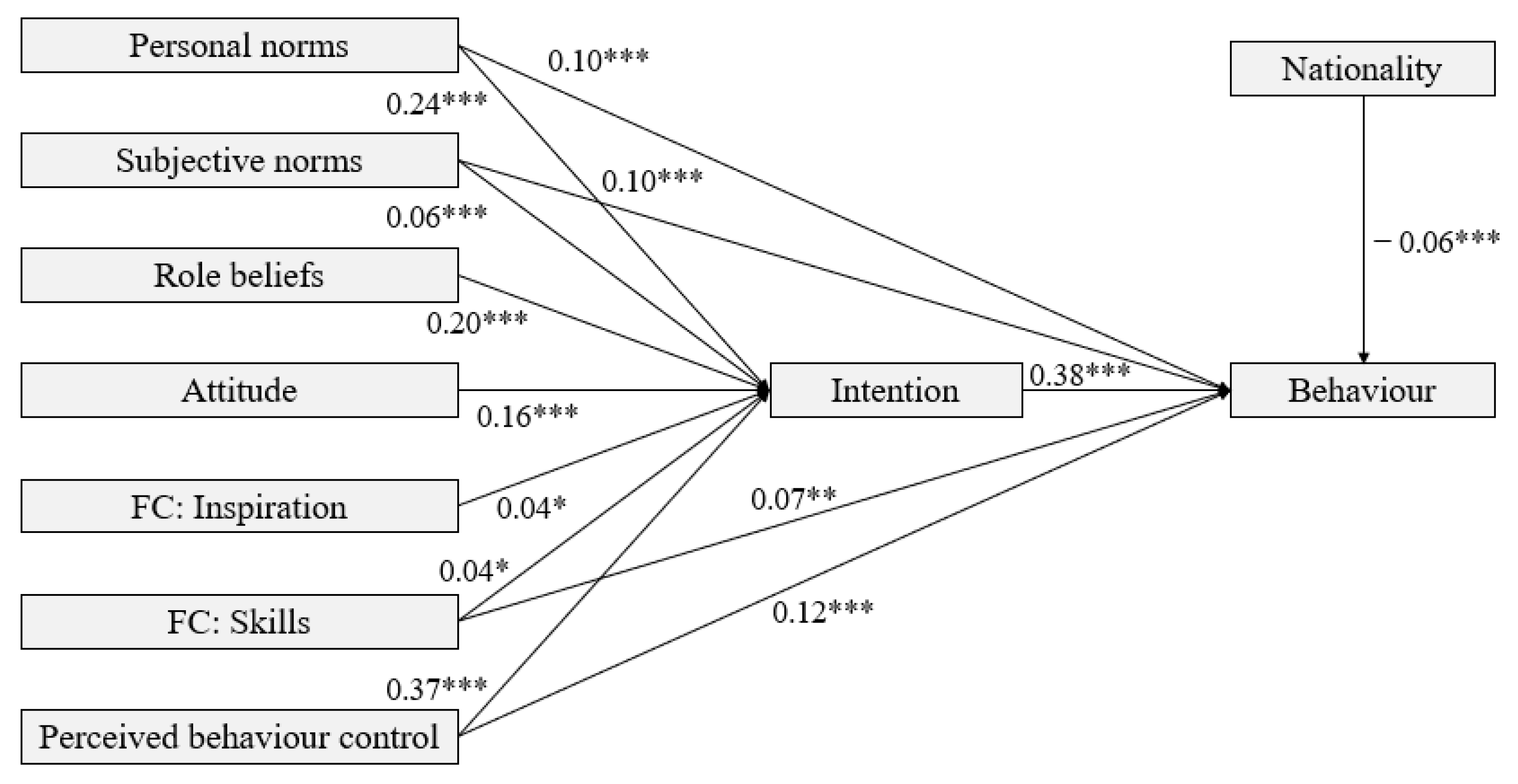

3.4. Confirming Predictors and Evaluating the Theoretical Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.M.; Cullen, J.M.; Carruth, M.A.; Cooper, D.R.; McBrien, M.; Milford, R.L.; Moynihan, M.C.; Patel, A.C. Sustainable Materials: With Both Eyes Open; UIT Cambridge Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K. Sustainable Production and Consumption by Upcycling: Understanding and Scaling up Niche Environmentally Significant Behaviour. Ph.D. Thesis, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; West, K.; Mont, O. Challenges and opportunities for scaling up upcycling businesses–The case of textile and wood upcycling businesses in the UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariatli, F. Linear economy versus circular economy: A comparative and analyzer study for optimization of economy for sustainability. Visegr. J. Bioeconomy Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Kettley, S. Individual upcycling practice: Exploring the possible determinants of upcycling based on a literature review. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Innovation 2014 Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 3–4 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, L.M.; Narancic, T.; Mampel, J.; Tiso, T.; O’Connor, K. Biotechnological upcycling of plastic waste and other non-conventional feedstocks in a circular economy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 62, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, G.; Kennedy, R.M.; Hackler, R.A.; Ferrandon, M.; Tennakoon, A.; Patnaik, S.; LaPointe, A.M.; Ammal, S.C.; Heyden, A.; Perras, F.A. Upcycling single-use polyethylene into high-quality liquid products. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiso, T.; Narancic, T.; Wei, R.; Pollet, E.; Beagan, N.; Schröder, K.; Honak, A.; Jiang, M.; Kenny, S.T.; Wierckx, N. Towards bio-upcycling of polyethylene terephthalate. Metab. Eng. 2021, 66, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, C.; Levendis, Y.A. Upcycling waste plastics into carbon nanomaterials: A review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, D.; Han, S. Upcycling fashion for mass production. In Sustainability in Fashion and Textiles: Values, Design, Production and Consumption, 1st ed.; Gardetti, M.A., Torres, A.L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 148–163. [Google Scholar]

- Cuc, S.; Tripa, S. Redesign and upcycling-a solution for the competitiveness of small and medium-sized enterprises in the clothing industry. Ind. Text. 2018, 69, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D. A case study engaging design for textile upcycling. J. Text. Des. Res. Pract. 2017, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslinger, S.; Hummel, M.; Anghelescu-Hakala, A.; Määttänen, M.; Sixta, H. Upcycling of cotton polyester blended textile waste to new man-made cellulose fibers. Waste Manag. 2019, 97, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charitha, V.; Athira, V.S.; Jittin, V.; Bahurudeen, A.; Nanthagopalan, P. Use of different agro-waste ashes in concrete for effective upcycling of locally available resources. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 285, 122851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essner, J.B.; Laber, C.H.; Ravula, S.; Polo-Parada, L.; Baker, G.A. Pee-dots: Biocompatible fluorescent carbon dots derived from the upcycling of urine. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matassa, S.; Papirio, S.; Pikaar, I.; Hülsen, T.; Leijenhorst, E.; Esposito, G.; Pirozzi, F.; Verstraete, W. Upcycling of biowaste carbon and nutrients in line with consumer confidence: The “full gas” route to single cell protein. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 4912–4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Jekle, M.; Becker, T. Opportunities for upcycling cereal byproducts with special focus on distiller’s grains. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, J. Recycling and Upcycling of Electronics. 2013. Available online: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/115305 (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Steinhilper, R.; Hieber, M. Remanufacturing-the key solution for transforming “downcycling” into “upcycling” of electronics. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Symposium on Electronics and the Environment, Denver, CO, USA, 9 May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Velis, C.A.; Franco-Salinas, C.; O’sullivan, C.; Najorka, J.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Cheeseman, C.R. Up-cycling waste glass to minimal water adsorption/absorption lightweight aggregate by rapid low temperature sintering: Optimization by dual process-mixture response surface methodology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 7527–7535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hummel, M.; Määttänen, M.; Särkilahti, A.; Harlin, A.; Sixta, H. Upcycling of waste paper and cardboard to textiles. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X. Upcycling of paper waste for high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries. Mater. Today Energy 2021, 19, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Wang, L.; Iris, K.M.; Tsang, D.C.; Poon, C. Environmental and technical feasibility study of upcycling wood waste into cement-bonded particleboard. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 173, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. When creative consumers go green: Understanding consumer upcycling. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D.; Silverman, J.; Dickson, M.A. Consumer interest in upcycling techniques and purchasing upcycled clothing as an approach to reducing textile waste. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2019, 12, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, C.; Vollero, A.; Siano, A. Consumer upcycling as emancipated self-production: Understanding motivations and identifying upcycler types. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Bringing Everyday Design into People’s Life: Design Considerations for Facilitating Everyday Design Behaviour. Ph.D. Thesis, Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, Ulsan, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Kettley, S. Factors influencing upcycling for UK makers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross Domestic Product at Current Market Prices of Selected European Countries in 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/685925/gdp-of-european-countries/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- List of North American Countries by GDP. Available online: http://statisticstimes.com/economy/north-american-countries-by-gdp.php (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Glaveanu, V.P.; Tanggaard, L.; Wegener, C. Creativity, a New Vocabulary; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, D.; Rennie, A.E.; Geekie, L.; Burns, N. Understanding powder degradation in metal additive manufacturing to allow the upcycling of recycled powders. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zeng, M.; Yappert, R.D.; Sun, J.; Lee, Y.H.; LaPointe, A.M.; Peters, B.; Abu-Omar, M.M.; Scott, S.L. Polyethylene upcycling to long-chain alkylaromatics by tandem hydrogenolysis/aromatization. Science 2020, 370, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Recent progress in the chemical upcycling of plastic wastes. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 4137–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanno, C.; Demarteau, J.; Mantione, D.; Arno, M.C.; Ruipérez, F.; Hedrick, J.L.; Dove, A.P.; Sardon, H. Selective chemical upcycling of mixed plastics guided by a thermally stable organocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 6710–6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, B.M.; de Vries, J.G. Chemical upcycling of polymers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2021, 379, 20200341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alammar, A.; Hardian, R.; Szekely, G. Upcycling agricultural waste into membranes: From date seed biomass to oil and solvent-resistant nanofiltration. Green Chemistry 2022, 24, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanescu, M.D. State of the art of post-consumer textile waste upcycling to reach the zero waste milestone. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 14253–14270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Xu, P.; Huang, H.; Yang, F.; Cao, M.; He, L.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J. Solar thermal catalysis for sustainable and efficient polyester upcycling. Matter 2022, 5, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Han, H.; Wu, Y.; Astruc, D. Nanocatalyzed upcycling of the plastic wastes for a circular economy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 458, 214422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Boruah, B.; Chin, K.F.; Đokić, M.; Modak, J.M.; Soo, H.S. Upcycling to sustainably reuse plastics. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacArthur, E. Towards the circular economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 2, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Stahel, W.R. The circular economy. Nature 2016, 531, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, R. The circular economy in China. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2017, 9, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Interpersonal Behavior; Brooks/Cole Publishing Company: Monterey, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.; Sánchez, E.; Pons, J.M. From recommendation to action: Psychosocial factors influencing physician intention to use health technology assessment (HTA) recommendations. Implement. Sci. 2006, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Motivating Sustainable Consumption: A Review of Evidence on Consumer Behaviour and Behavioural Change. 2005. Available online: Chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://timjackson.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Jackson.-2005.-Motivating-Sustainable-Consumption.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Bamberg, S.; Schmidt, P. Incentives, morality, or habit? predicting students’ car use for university routes with the models of Ajzen, Schwartz, and Triandis. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a TPB Questionnaire: Conceptual and Methodological Considerations. 2002. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Constructing-a-TpB-Questionnaire%3A-Conceptual-and-Ajzen/6074b33b529ea56c175095872fa40798f8141867 (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A.; Siguaw, J.A. Introducing LISREL: A Guide for the Uninitiated, 1st ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J.H. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, V.; Wesselink, R.; Studynka, O.; Kemp, R. Encouraging sustainability in the workplace: A survey on the pro-environmental behaviour of university employees. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Seixas, R. Understanding high school students’ attitude, social norm, perceived control and beliefs to develop educational interventions on sustainable development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 143, 1200–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Understanding consumer recycling behavior: Combining the theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2014, 42, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Hancer, M. The role of attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and moral norm in the intention to purchase local food products. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. Human values and the emergence of a sustainable consumption pattern: A panel study. J. Econ. Psychol. 2002, 23, 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Shaw, D. Who says there is an intention–behaviour gap? assessing the empirical evidence of an intention–behaviour gap in ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, D.J.; O’Leary, J.E. The theory of planned behaviour: The effects of perceived behavioural control and self-efficacy. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 34, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliot, A.J.; Thrash, T.M. Approach-avoidance motivation in personality: Approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 804–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orîndaru, A.; Popescu, M.; Căescu, Ș.; Botezatu, F.; Florescu, M.S.; Runceanu-Albu, C. Leveraging COVID-19 outbreak for shaping a more sustainable consumer behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Steg, L.; Dietz, T. Insights from early COVID-19 responses about promoting sustainable action. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruepert, A.M.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L. The relationship between corporate environmental responsibility, employees’ biospheric values and pro-environmental behaviour at work. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Beyers, W.; Boone, L.; Deci, E.L.; der Kaap-Deeder, V.; Duriez, B.; Lens, W.; Matos, L.; Mouratidis, A. Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Elliot, A.J.; Kim, Y.; Kasser, T. What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janigo, K.A.; Wu, J.; DeLong, M. Redesigning fashion: An analysis and categorization of women’s clothing upcycling behavior. Fash. Pract. 2017, 9, 254–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Values, norms, and intrinsic motivation to act proenvironmentally. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Questions (Items) and Answer Options |

|---|---|

| Attitudes | How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements? To me, taking part in upcycling is ‘good’. To me, taking part in upcycling is ‘pleasant’. To me, taking part in upcycling is ‘worthwhile’.

|

| Perceived facilitating conditions | To what extent do you think: ‘access to tools’ has facilitated your upcycling? ‘used or waste products, components, or materials available’ have facilitated your upcycling? ‘teachers or helpers’ have facilitated your upcycling? ‘skills and knowledge’ have facilitated your upcycling? ‘inspiration’ has facilitated your upcycling? (1: not at all–5: to a very great extent) |

| Personal norms (social factor 1) | How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement? I would ‘feel guilty if I was not upcycling’, especially when used materials are available and would become waste otherwise. Upcycling ‘reflects my principles’ about using resources responsibly. It would be ‘unacceptable to me not to upcycle’, especially when used materials are available and would become waste otherwise. (1: strongly disagree–5: strongly agree) |

| Role beliefs (social factor 2) | How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements? Upcycling fits my role in ‘my family’. Upcycling fits my role in ‘my community’. Upcycling fits my role in ‘my friendship/support networks’. (1: strongly disagree–5: strongly agree) |

| Subjective norms (social factor 3) | How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements? Most people who are important to me think that ‘I ought to’ upcycle. Most people who are important to me ‘expect’ me to upcycle. Most people who are important to me ‘would approve’ of me upcycling. (1: strongly disagree–5: strongly agree) |

| Perceived behavioural control | How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement? For me upcycling would be possible. If I wanted to, I could upcycle. Upcycling would be easy for me. (1: strongly disagree–5: strongly agree) |

| Intention | How much do you agree or disagree with the following statement? My likelihood of upcycling is high. If I have the opportunity, I will upcycle. I intend to upcycle. (1: strongly disagree–5: strongly agree) |

| Frequency of upcycling | Approximately how often have you upcycled items in the past five years? (1: never; 2: less frequently than once a year; 3: about once a year; 4: about once every six months; 5: about once every three months; 6: about once a month; 7: about once a week; 8: more frequently than once a week) |

| Demographic Factor | Category | Frequency (Percentage) |

|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Australia Canada Germany UK USA | 351 (20.1%) 353 (20.2%) 341 (19.6%) 349 (20.0%) 350 (20.1%) |

| Gender | Female Male Others (non-binary) | 885 (50.7%) 834 (47.8%) 25 (1.4%) |

| Age group | Under 30 30 to 49 50 and over | 785 (45.0%) 781 (44.8%) 178 (10.2%) |

| Employment status | Full-time employment Part-time employment Self-employment Not currently in employment 1 | 811 (46.5%) 353 (20.2%) 170 (9.7%) 410 (23.5%) |

| Occupational area | Business, marketing, sales, and management Science and engineering Teaching and education Creative arts and design Healthcare, public sector, and laws Student, homemaker, retired, and unemployed Others 2 Missing | 443 (25.4%) 425 (24.4%) 267 (15.3%) 153 (8.8%) 128 (7.3%) 152 (8.7%) 175 (10.0%) 1 (0.1%) |

| Factor | Items | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | Good Pleasant Worthwhile | 4.50 3.86 4.29 | 0.65 0.90 0.79 |

| Perceived facilitating conditions | Access to tools Used or waste products, components, or materials available Teachers or helpers Skills and knowledge Inspiration | 3.71 3.68 2.70 3.75 3.90 | 0.98 0.95 1.22 1.01 1.05 |

| Personal norms (social factor 1) | I would ‘feel guilty if I was not upcycling’ Upcycling ‘reflects my principles’ It would be ‘unacceptable to me not to upcycle’ | 3.48 3.94 3.44 | 1.17 0.98 1.17 |

| Role beliefs (social factor 2) | My family My community My friendship/support networks | 3.23 3.13 3.02 | 1.09 1.12 1.12 |

| Subjective norms (social factor 3) | Most people who are important to me think that ‘I ought to’ upcycle. Most people who are important to me ‘expect’ me to upcycle. Most people who are important to me ‘would approve’ of me upcycling. | 2.72 2.34 4.11 | 1.12 1.15 0.89 |

| Perceived behaviour control | For me upcycling would be possible. If I wanted to, I could upcycle. Upcycling would be easy for me. | 4.10 4.18 3.40 | 0.85 0.85 1.04 |

| Intention | My likelihood of upcycling is high. If I have the opportunity, I will upcycle. I intend to upcycle. | 3.64 4.02 3.87 | 1.05 0.92 1.02 |

| Category | Answer Option | N | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of upcycling | Never Less frequently than once a year About once a year About once every six months About once every three months About once a month About once a week More frequently than once a week | 96 183 248 356 370 320 121 50 | 5.5 10.5 14.2 20.4 21.2 18.3 6.9 2.9 |

| Impact of COVID-19 pandemic | Yes, I became engaged in upcycling ‘less’ frequently No Yes, I became engaged in upcycling ‘more’ frequently | 170 1071 503 | 9.7 61.4 28.8 |

| Variable | Item(s) | Wald | df | p | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | To me, taking part in upcycling is ‘worthwhile’ | 35.946 | 1 | 0.000 ** | 1.784 |

| Personal norms | I would ‘feel guilty if I was not upcycling’ | 59.649 | 1 | 0.000 ** | 1.698 |

| Role beliefs | Upcycling fits my role in ‘my family’ | 46.154 | 1 | 0.000 ** | 1.680 |

| Subjective norms | Most people who are important to me ‘expect’ me to upcycle | 12.833 | 1 | 0.000 ** | 1.284 |

| Perceived behaviour control | For me upcycling would be possible | 157.895 | 1 | 0.000 ** | 3.692 |

| Perceived facilitating conditions | Available used/waste products and materials Skills and knowledge Inspiration | 1.709 1.832 2.063 | 1 1 1 | 0.191 0.176 0.151 | 1.112 1.111 1.112 |

| Nationality | Nationality | 0.086 | 1 | 0.769 | 1.014 |

| Constant | 335.202 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Variable | Item(s) | Wald | df | p | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes | To me, taking part in upcycling is ‘worthwhile’ | 0.243 | 1 | 0.622 | 0.959 |

| Personal norms | I would ‘feel guilty if I was not upcycling’… | 5.124 | 1 | 0.024 ** | 1.148 |

| Role beliefs | Upcycling fits my role in ‘my family’ | 1.870 | 1 | 0.172 | 1.094 |

| Subjective norms | Most people who are important to me ‘expect’ me to upcycle | 5.932 | 1 | 0.015 ** | 1.145 |

| Perceived behaviour control | Upcycling would be easy for me | 36.575 | 1 | 0.000 ** | 1.517 |

| Perceived facilitating conditions | Available used/waste products and materials Skills and knowledge Inspiration | 0.962 12.509 4.360 | 1 1 1 | 0.327 0.000 ** 0.037 ** | 1.070 1.265 0.875 |

| Intention | My likelihood of upcycling is high | 69.042 | 1 | 0.000 ** | 2.060 |

| Nationality | Nationality | 3.600 | 1 | 0.058 | 0.927 |

| Constant | 156.223 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sung, K.; Ku, L.; Yoon, J.; Kim, C. Predictors of Upcycling in the Highly Industrialised West: A Survey across Three Continents of Australia, Europe, and North America. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021461

Sung K, Ku L, Yoon J, Kim C. Predictors of Upcycling in the Highly Industrialised West: A Survey across Three Continents of Australia, Europe, and North America. Sustainability. 2023; 15(2):1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021461

Chicago/Turabian StyleSung, Kyungeun, Lis Ku, JungKyoon Yoon, and Chajoong Kim. 2023. "Predictors of Upcycling in the Highly Industrialised West: A Survey across Three Continents of Australia, Europe, and North America" Sustainability 15, no. 2: 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021461

APA StyleSung, K., Ku, L., Yoon, J., & Kim, C. (2023). Predictors of Upcycling in the Highly Industrialised West: A Survey across Three Continents of Australia, Europe, and North America. Sustainability, 15(2), 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021461