1. Introduction

With the growing demand for integrating Information and Communication Technology (ICT) into K-12 education worldwide, fostering teachers’ use of open educational resources (OER) to support their teaching process is an important research topic in the field of educational technology [

1,

2]. The use of OER is important in teachers’ pedagogical practices to elevate their instructional skills. These resources also enable, promote, and develop educational quality and equity that fit the educational demands of the knowledge society. As in many other countries, the educational authorities in the People’s Republic of China have been putting substantial efforts into implementing OER with the aim of accomplishing digital equity in education [

3].

OER refers to learning, teaching, and research materials in any format or medium that reside in the public domain or are under copyright and have been released under an open license that permit no-cost access, reuse, repurposing, adaptation, and redistribution by others [

4]. OER are available in the form of textbooks, lecture notes, assignments, tests, projects, audio, video, and animation. Furthermore, new and experimental types of OER are emerging such as immersive environments, simulations, illustrations, and digital assessments [

5]. OER can promote and support innovative pedagogical models, accommodate diverse learner needs, and motivate teachers’ reflection on their teaching [

6]. Moreover, integrating OER in K-12 teaching practice is a powerful way for teachers to develop their professional skills in effectively deploying educational technology through a learning-by-doing approach [

7].

Even though OER is considered to potentially add value to teachers’ instruction, previous research found that individual and contextual factors such as teachers’ intentions and attitudes regarding their use of digital learning materials [

5] and school organizational variables [

8] significantly influenced teachers’ use of OER. However, the quality of OER as a potentially crucial factor was hardly studied. Indeed, how the quality of OER and the rest of the known factors might interact with each other could produce unexpected outcomes in teachers’ willingness to persistently utilize OER. Therefore, to gain more holistic insights into the relationship between teachers’ perceptions and actual usage of OER, it is crucial to investigate the influence of the three types of factors (quality of OER, teacher-related and school-related factors) [

9].

We constructed a guiding theoretical framework for the study by synthesizing the literature based on the integrative model of behavior prediction (IMBP) to account for teachers’ integration of ICT in education [

10,

11]. The relevant measures of distal and proximal factors that affect teachers’ usage of OER were identified. Subsequently, exploratory factor analysis, multiple linear regression, and structural equation modeling were performed to discern the correlations and paths between factors and the outcomes under consideration. The study is intended to reveal the factors affecting teachers’ use of OER in China so that some intervention can be found to support this and strengthen ICT integration in K-12 classrooms.

2. Theoretical Framework

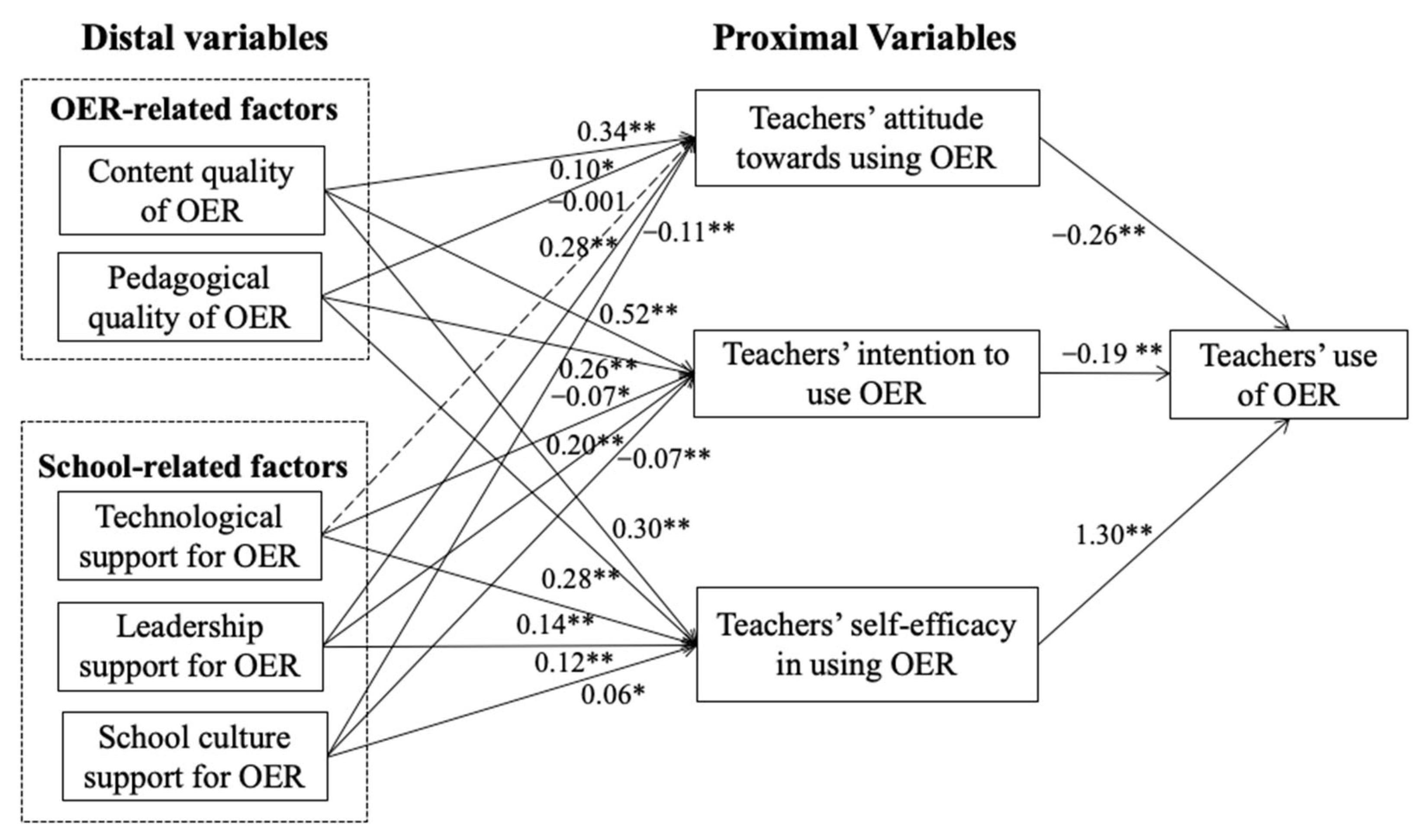

In this study, we adapted the integrative model of behavior prediction (IMBP) to investigate the factors impacting Chinese teachers’ use of OER. As a seminal theoretical framework, the IMBP conceptualizes that two types of variables, proximal and distal variables, influence the cognitive process of self-regulation with respect to the desired behavior, here teachers’ use of OER in education. In this case, the proximal variables are teacher-related, such as self-efficacy, attitude, intention, and other dispositional variables. The distal variables are those that are external to the teachers themselves, such as variables at the school level. As the IMBP is a flexible framework for analysis, it can be adapted by refining specific variables or adding new variables [

12,

13]. Therefore, we adapted the IMBP by incorporating an OER-related variable (the quality of OER) into the distal variable group (together with the school-related variables), as shown in

Figure 1.

2.1. Teacher-Related Factors Related to the Use of OER

In particular, teachers’ attitude toward using OER refers to their overall feeling of affinity for or antipathy to the consequences or outcomes [

14]. Prior research showed that there is a strong relationship between teachers’ attitude toward using OER and their integration of OER [

15]. When teachers have a positive attitude, they will be more likely to utilize OER. Not all teachers, even those who regularly use OER, have a negative attitude. Teachers who resist adopting OER are less likely to adapt their teaching behaviors [

16].

Self-efficacy is the “belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to manage prospective situations” [

17]. However, it does not reflect whether the individual actually has the necessary competency. Even if difficulties exist in the process of integrating OER, self-efficacy acts as a driving force, allowing teachers to consciously overcome the odds and maximize the value of OER in their instruction. It was found that teachers’ self-efficacy with regard to ICT could predict the quality of their integration of ICT [

18]. Teachers with positive self-efficacy are more likely to utilize ICT to facilitate student-centered learning and develop students’ higher-order thinking skills.

Teachers’ intention to use OER influences the possibility of integrating OER into their teaching in the future [

19]. According to the theory of planned behavior, when an individual has a certain behavioral intention, that individual is more likely to engage in that behavior [

20]. Therefore, intention is viewed as a factor that predicts the individual’s practical behaviors.

2.2. School-Related Factors Related to Teachers’ Use of OER

In terms of school-related factors, earlier research demonstrated that teachers’ use of technology was influenced by two factors: contextual characteristics (e.g., ICT infrastructure, software) and cultural characteristics (e.g., school leadership, school ICT policy) [

1]. Therefore, in this study, we focused on one contextual factor (technical support of OER) and two cultural factors (leadership and school cultural support for OER) against the background of teachers’ use of OER.

Technical support for OER plays an important role in teachers’ use of OER [

21]. Teachers often encounter technical challenges when they employ OER in their teaching, such as Internet connection, software applications, access to hardware, and customizability or reusability. Without adequate technical support, teachers are unlikely to overcome the barriers that prevent routine and effective OER use [

22].

Leadership support and school cultural support for OER affect teachers’ use of OER [

23]. Although teachers are free to determine their classroom teaching practices in China, as in many other countries, the support of OER adoption by school leaders influences teachers’ use of OER [

24]. School leaders are responsible for determining the vision and plan for integrating ICT in their school, which will provide direction for teachers’ practices. When school leaders take action to demonstrate the value of OER in teaching practices, its adoption will be seen as necessary and useful [

8].

School culture is defined as “the basic assumptions, norms and values, and cultural artifacts that are shared by school members, which influence their functioning at school” [

25]. Teachers’ perceptions of cultural support affect their integration of ICT. If schools develop a supportive culture for teachers to implement ICT, teachers will be more inclined to use OER in their teaching [

26].

2.3. OER-Related Factors Related to Teachers’ Use of OER

The quality of OER is another factor that should be taken into consideration when exploring the factors that directly and indirectly influence teachers’ use of OER [

27]. OER can have different levels of granularity or sizes (e.g., from OpenCourseWare to independent educational resources) and types (e.g., images, videos, podcasts, text, slides) [

28]. Therefore, OER quality should be characterized or evaluated in terms of multiple perspectives and dimensions. For example, four key activities were identified when people use repositories of OER: searching, sharing, reusing, and collaborating [

29]. These four activities were then further unpacked to reveal 10 key indicators underpinning the quality assessment of repositories. They are featured resources, evaluation by users, peer evaluation, authorship of resources, use of keywords, implementation of metadata systems, multilingual support, support for social networks, Creative Commons licenses, and access to downloads of original files and/or source code. Three dimensions of OER quality were identified in [

30]—content, format, and process—focusing on learner-generated content. A three-level framework was proposed in [

28] to evaluate the quality of OER in order to promote the discovery and reuse of resources by users based on emergent technology.

From the perspective of teachers, the quality of OER refers to the extent that the OER meets their needs and requirements for classroom teaching [

31]. Certain frameworks are suitable to assess the quality of OER from this perspective. For example, a framework to evaluate web-based learning resources in the school education context was proposed in [

32], comprising two main criteria: technological usability and pedagogical usability. Technical usability refers to techniques for ensuring trouble-free interaction with the technology, while pedagogical usability refers to supporting teachers’ instructional processes. Similarly, the Learning Object Review Instrument (LORI) was developed to evaluate the quality of multimedia resources for use in learning [

33]. The instrument measures learning objects in nine aspects: content quality, learning goal alignment, feedback and adaption, motivation, presentation design, interaction usability, reusability, accessibility, and standards compliance.

Some studies have explored the effect of teachers’ perception of OER quality on their intention to adopt OER mediated by teacher-related factors such as their attitude toward OER [

34]. Yet there are few empirical studies on how the three types of factors (quality of OER, teacher-related and school-related factors) influence teachers’ use of OER.

2.4. Research Questions

Informed by the literature, we crafted three research questions to guide our study. First, the context of teachers’ usage of OER is different in China than in other countries because K-12 teachers access OER in the Chinese language. Whether the findings from prior studies conducted elsewhere were applicable to China was unknown. Thus, the first research question arose from the intention to generate context-sensitive findings in this aspect:

RQ1: What are the distal and proximal factors related to teachers’ use of OER in Chinese K-12 education?

Second, less attention had been paid to the effect of distal OER-related factors on teachers’ usage of OER. When taking these factors into consideration, how the OER-related and school-related factors influence teachers’ use of OER was unknown. Therefore, the second research question is:

RQ2: How do the identified distal factors, OER-related and school-related factors, jointly influence teachers’ use of OER in Chinese K-12 education?

Third, according to the IMBP, the relationships of distal factors and outcome factors should be mediated by proximal factors. Therefore, the third research question is:

RQ3: How are the identified distal factors of teachers’ usage of OER mediated by the identified proximal factors in Chinese K-12 education?

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context and Participants

In the study, a questionnaire instrument was developed, informed by the analytic model shown in

Figure 1, to investigate the effects of OER-related, school-related, and teacher-related factors on teachers’ use of OER in China. It was distributed electronically by the National Center for Educational Technology to public school teachers nationwide. The participation was voluntary and anonymous; i.e., respondents were not required to submit individually identifiable data. Eventually, 1398 questionnaires were returned for analysis. The sample distribution of demographic variables is shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Measures

Besides a demographics section, the questionnaire comprised measurement items of the factors mentioned in the literature review. The subscale structure of the instrument is shown in

Table 2.

For the teacher-related factors, teachers’ intention to use OER was measured by two items adopted from [

35] rated on a 5-point scale; a sample item is “I plan to use digital learning materials during class regularly”. Teachers’ self-efficacy in the use of OER was measured with four items from [

14] rated similarly; a sample item is “I am confident that I can use digital learning materials during class regularly”. Teachers’ attitude toward using OER was measured with five bipolar items reflecting instrumental and affective dimensions [

35]. Two items (valuable–worthless, meaningful–meaningless) were used to measure the instrumental dimension and three items (boring–fun, dull–exciting, and fantastic–horrible) to measure the affective dimension.

Three subscales related to the school-related factors were incorporated. Technological support for OER was measured by three items based on the work of [

21]; a sample item is “I could receive technical support for the OER platform I used in a timely manner”. Leadership support for OER was measured by three items, which were adapted from [

36]; a sample item is “There was strong administrative backing for using OER”. School culture support for OER was measured by five items adapted from [

37]; a sample item is “My school often organized workshops to discuss the issues of using OER”. All items were measured on a 5-point rating scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”.

As for the OER-related factors, nine items from the LORI framework were incorporated [

33] to assess teachers’ perception of the quality of OER; a sample item is “The OER I accessed showed veracity and accuracy”. All items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”.

Lastly, two items in the questionnaire were used to evaluate teachers’ use of OER based on [

38]: “I can easily access the OER I want to use” and “I can access the OER that can fulfill my instructional requirement”. These were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “absolutely disagree” to “absolutely agree”.

3.3. Data Analyses

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to verify the distal and proximal factors related to teachers’ use of OER. Based on the results of EFA, the mean scores of items belonging to the individual constructs were calculated. Then multiple linear regression was employed to test how the identified external factors jointly impact teachers’ use. Finally, structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted with AMOS 7.0 to explore how the proximal factors mediated the effect of distal factors on teachers’ use of OER.

4. Results

4.1. Distal and Proximal Factors Related to Teachers’ Use of OER

In order to explore whether the theoretical factors are indeed related to teachers’ use of OER in China, we evaluated the questionnaire data using exploratory factor analysis. First, we found that the data met the criteria for multivariate analysis. Initially, Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the KMO test were applied to the dataset; the value of the latter was 0.97 (

p > 0.05), and Bartlett’s test was significant (

p < 0.01). Principal component analysis was then used to extract the factors. Factors with salient loading (greater than 0.40) were subjected to rotation to clarify the constructs. Eight constructs were identified, as shown in

Table 3.

In line with our theoretical expectation, three constructs were extracted from the teacher-related factors: intention to use OER, self-efficacy in using OER, and attitude toward using OER. There were also three constructs related to the school-related factors: technological support, leadership support, and school culture support for OER.

However, not in line with our theoretical expectation, two constructs, content quality and pedagogical quality of OER, were extracted from only seven items measuring the quality of OER factor. As shown in

Table 3, four items loaded into a new construct: evaluating content design, learning goal alignment, motivation, and presentation design. Through examining and relating the items loaded on the construct, we named the first construct content quality of OER. It focused more on elements such as whether OER was aligned with the curriculum, was accurate, or was suitable for learners’ cognitive levels. In addition, three other items were loaded into the new construct: evaluating interaction usability, reusability, and feedback. Through examining and relating the items loaded on the construct, we named the second construct pedagogical quality of OER. It concentrated more on whether OER supports teachers’ instructional processes [

39].

The internal reliability of individual subscales was examined next.

Table 3 shows the questionnaire items and their factor loadings on the constructs and the reliability determined by Cronbach’s alpha. All resulting Cronbach’s alpha values were above 0.80. The overall Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale for teachers’ use of OER was 0.85. These indicate that individual subscales had highly reliable internal consistency. Therefore, it can be concluded that the eight factors shown in

Table 3 are related to K-12 teachers’ use of OER in China.

4.2. Influence Mechanism of Teachers’ Use of OER

4.2.1. Teachers’ Use of OER Influenced by Distal Factors

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics of the eight identified distal and proximal factors and their correlations. It was found that the eight factors are significantly related.

To investigate the effect of the distal factors on teachers’ use of OER in China, multiple regression analysis was performed, as shown in

Table 5. It was found that 55% of the variance in teachers’ use of OER was explained by five of the OER-related and school-related factors in the model (R2 = 0.98, F(51,393) = 11,218.72,

p < 0.05): pedagogical quality of OER (β = 0.40,

p < 0.05), content quality of OER (β = 0.33,

p < 0.05), school culture support for OER (β = 0.22,

p < 0.05), and technological support for OER (β = 0.21,

p < 0.05). On the other hand, leadership support for OER showed a negative impact on teachers’ use of OER (β = −0.17,

p < 0.001). This means that among the five distal variables, OER-related factors are stronger predictors of teachers’ use of OER as compared to school-related factors. As for the school-related factors, school culture support and technological support for OER positively impact Chinese K-12 teachers’ use of OER, while leadership support has a negative impact.

4.2.2. Effect of Distal Factors on Teachers’ Use of OER Mediated by Proximal Factors

SEM was used to test the fit between the proposed model and the collected data (see

Figure 1) because of its ability to examine sets of dependence relationships concurrently, especially when there are both direct and indirect effects among the variables within the model [

40]. In this study, SEM was conducted to explore how the proximal and distal factors influenced teachers’ use of OER. Multiple indices were used to evaluate the model fit: χ

2, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), normed fit index (NFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The recommended level of acceptable fit and the fit indices for the proposed path model are shown in

Table 6. The values indicate that there is a satisfactory model fit because they all exceed the threshold.

The path coefficients of the proposed model are shown in

Figure 2. First, except for the Technological support for OER—> Attitude towards using OER path, the other paths shown in the figure are significant at the 0.05 level. Second, in contrast with the school-related factors, the OER-related factors indirectly predict teachers’ use of OER. Third, the relationship between OER-related factors and teachers’ use of OER is largely positively mediated by teachers’ self-efficacy in using OER (β = 1.30,

p < 0.05) and less negatively mediated by teachers’ intention to use OER (β = −0.19,

p < 0.05) and teachers’ attitude toward using OER (β = −0.26,

p < 0.05). Therefore, it can be concluded that the effect of the five distal factors on teachers’ use of OER was mediated by the three proximal factors.

5. Discussion

The goal of the study was to investigate the factors that influence teachers’ use of OER in K-12 education and their interactions in order to understand the situation of teachers’ OER adoption in China. EFA was used to identify eight distal and proximal factors that were related to teachers’ use of OER in K-12 education in China. We further explored how these factors affected teachers’ use of OER directly and indirectly using multiple regression analysis and SEM. The main findings of the study are discussed below.

Contrary to our expectation, which was grounded in the prior literature, eight factors rather than seven emerged from the data. With respect to the proximal factors, three constructs were identified: teachers’ attitude toward using OER, teachers’ intention to use OER, and teachers’ self-efficacy in using OER. Regarding the distal factors, there were three school-related factors: technological support, leadership support, and school cultural support for OER, and two OER-related factors, content quality and pedagogical quality of OER. Different from the theoretical assumption from the prior literature, the items designed to evaluate one construct, quality of OER, was divided into two constructs, content quality and pedagogical quality of OER. This suggests that in order to promote teachers’ use of OER in the K-12 educational setting, these two quality-related aspects should be taken into account. Addressing each of the extracted eight factors provides a good starting point for us to understand the situation of teachers’ use of OER in China.

As shown in the Results section, incorporating the quality of OER factor in the statistical analysis reshaped the dynamics among the remaining relevant factors. This provides a more holistic view for an understanding of teachers’ use of OER in China.

5.1. OER Quality Matters Most for Teachers’ Use of OER

As shown in

Table 5 and

Figure 2, it was found that OER-related factors are stronger positive direct and indirect predictors of teachers’ use of OER in China, which received little attention in previous research. In terms of the OER-related factors, pedagogical quality had a stronger effect than content quality. Thus, one implication is that if Chinese K-12 teachers were aware that OER was useful and valuable in supporting their pedagogical practice, they would be more willing to adopt it in their instruction. Next, content quality was also found to affect teachers’ use of OER. It is suggested that if the content of a given OER was aligned with the topic of instruction and suitable for the learners’ cognitive level, teachers would be more likely to use it in their classes. These findings affirm that the quality of OER is essential for OER adoption when taking other possible benefits or barriers into consideration [

41]. To scale up the use of OER in formal educational settings, it is best to focus on creating suitable OER for the classroom context from the teachers’ perspective [

42].

5.2. Reconsider the Role of School Leadership in Teachers’ Use of OER

As shown in

Table 5, among the distal school-related factors, it was found that technological support and school culture support for OER had a positive impact on teachers’ use of OER. However, unexpectedly it was also found that leadership support for OER had a negative impact. This contradicts prior findings [

43], which could provide a more in-depth understanding of the factors affecting teachers’ use of OER in K-12 education in China.

The unexpected findings can be explained by the supposition that school leaders may not have adequate know-how to empower teachers to adopt OER effectively because of a lack of professional background, prior experience, or knowledge foundation related to OER adoption [

44]. Thus, leadership support for OER as a mere formality would not necessarily result in a positive impact on teachers’ adoption [

45]. When it comes to the choice of adopting OER or not, teachers are typically goal-oriented. If they do not observe any instructional effects from OER in their lessons, they may not be inclined to continue using OER. Therefore, to foster teachers’ use of OER, besides systemic expectations and encouragement by school leaders, substantive practical support from school management would be equally crucial.

As shown in

Table 5, OER-related factors are the strongest predictor of teachers’ use of OER. Therefore, school leaders should provide teachers with the high-quality OER they need. Furthermore, in order to create a positive school culture that supports teachers’ use of OER, professional development opportunities should be provided for acquiring strategies of OER adoption [

46] and strategies should be implemented to address the context-related challenges of OER adoption due to time and resource constraints that hinder its integration [

2].

5.3. Levelling Up the Effort to Improve Teachers’ Self-Efficacy in the Use of OER

As shown in

Figure 2, among the proximal teacher-related factors in the study, only teachers’ self-efficacy in using OER positively mediated the effect of the two categories of distal factors on teachers’ use of OER in China. That is, if the threshold of the external barriers for teachers’ use of OER was overcome, the salient factor influencing this was self-efficacy [

47]. The results are in line with the findings of previous studies showing that teachers’ self-efficacy played an important role in integrating technology into classroom practice [

26]. This implies that a promising strategy for promoting teachers’ use of OER is to develop and foster their self-efficacy.

Notwithstanding, an unexpected finding from our analysis (

Figure 2) was that both teachers’ intention and attitude negatively predicted their use of OER. Prior research in Western countries found that teachers’ intention and attitude were the strongest positive predictors of their OER use [

14]. Instead, while teachers in China had stronger intention, they were less inclined to integrate OER into their lessons. This means that there were some external barriers for teachers that not only “neutralized” but even “overrode” their intention to utilize OER [

48].

According to

Figure 2, among the five distal factors, content quality, pedagogical quality, and leadership support had the most predictive power with regard to teachers’ intention to use OER. This surprising finding may have two possible explanations, from the OER-related perspective and the school-related perspective. From the OER-related perspective, the inferior content and pedagogical quality of the OER accessible by the teachers may have reduced their willingness to adopt OER. There are two main channels through which Chinese teachers acquire OER: OER designed and shared by colleagues nationwide in a bottom-up manner and commercial OER developed by educational publishers [

49]. Teacher-developed OER packages are typically underpinned by behaviorism and match typical Chinese teachers’ traditional epistemological beliefs and educational philosophy, rather than cognitivism or constructivism. That is, they expect students to be spoon-fed the content of the OER, rather than the OER facilitating active and autonomous learning. On the other hand, commercial OER is typically developed by private education publishers. Due to the latter’s lack of understanding of teachers’ instructional practices, it is hard to localize, customize, and contextualize such OER into teachers’ instructions. In this regard, there is room for improvement in the quality of OER for greater alignment with teachers’ needs.

From the school-related perspective, school leaders’ expectation that teachers would successfully use OER tended to be greater than their efforts to provide it and support the use of digital education resources [

50]. In this case, the lack of proper leadership support may deter teachers’ actual OER adoption, despite being motivated to do so.

6. Implications

The above expected and unexpected findings may shed light on the situation of teachers’ use of OER in China. They may also provide us with insights into the future development of OER and promotion of teachers’ use of OER.

First, quality is the main factor influencing Chinese teachers’ use of OER. To boost the adoption rate of OER in China, it is crucial to elevate the content and pedagogical quality. The OER provided to teachers should be aligned to the curriculum standards and the context of the lessons. Furthermore, the OER should be designed for easy integration and customization within teachers’ pedagogical processes with little effort. More specifically, according to the national survey on Chinese K-12 teachers’ use of OER [

51], teachers typically adopt two types. The first type of OER is content-related, in the form of audio clips, video clips, animations, or other multimedia types. The second type of OER is pedagogically related, such as lesson plans, lecture notes, assignments, and instruments for assessment. How to promote teachers’ experimentation and adoption of alternative types of OER to facilitate cognitivist or constructivist lesson plans is a potentially important research topic. In addition, as indicated in the previous section, the formation of communities for sharing, peer critique, and even co-construction of OER would be an important strategy to elevate the quality [

52]. As China is a non-English-speaking country, teachers and students are hampered by the language barrier, and it is difficult to adapt quality OER in English on the Internet [

53]. Thus, further efforts should be made to support the fluid exchange of OER between English-speaking and non-English-speaking countries.

Second, to promote the use of OER, emphasis should be placed on improving teachers’ self-efficacy in adopting OER. The way teachers use curricula is naturally a process of design. Participating in the design process can help them learn new content and skills and push them to reflect upon the strengths and shortfalls of their existing teaching practice and evaluate their students’ needs [

54]. A design-based approach in workplace learning provides teachers the opportunity to learn how to use specific technologies in the context of their curricular needs. After being involved in the design for adopting OER, teachers would be more likely to take ownership of OER and have greater confidence when integrating it into their lessons. Furthermore, teachers’ engagement with curricula and other high-quality materials used to design instructional activities could significantly enhance students’ learning [

55]. Therefore, facilitating teachers’ experimentation using a design-based approach has been proposed as an effective way to increase their self-efficacy in adopting OER. The next step may be to explore how to encourage teachers to use the design-based approach to design high-quality OER in order to enhance their self-efficacy.

Third, developing positive systemic and cultural support for teachers’ use of OER should be addressed. Our study found that leadership support had a negative effect on teachers’ attitude toward and intention to adopt OER, which resulted in a negative impact on their use of OER. This indicated that not a single factor but rather a mix of various factors influenced teachers’ use of OER [

8]. Although school leaders have pushed teachers to use OER, they have not constructed a conducive ecological system for that purpose [

56]. Therefore, building a positive culture for the use of OER among Chinese K-12 teachers should be emphasized.

Furthermore, the school leaders’ capacity for pedagogical leadership should be improved. Leaders should not only support classroom teachers in their key role of implementing OER, but also influence their instruction by establishing organizational norms of continuous quality improvement [

57]. For school organizations, school culture includes the visions, plans, norms, and values that are shared by members of the school community [

25]. The facilitation of and support for OER adoption should be written into schools’ technology integration plans, which will help foster and sustain a school culture that supports teachers’ use of OER. Teachers’ actions related to OER adoption, such as planning lessons and designing materials, and the experiences and problems they encounter should be shared with other teachers to encourage peer support. School leaders should have open conversations with teachers, learn about their challenges, and work together with them to develop solutions to address problems. Furthermore, new professional development programs should be launched to build teachers’ capacity to develop quality OER that privileges learner autonomy and students’ knowledge construction over content delivery. Some routine administrative tasks should be offloaded from teachers, so that they can set aside time to foster their OER adoption skills and form a professional learning community to learn, design, implement, reflect on, and improve OER adoption together.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Studies

The findings of the study, in addition to shedding light on the context of OER adoption and the strategies to increase it in China from the teachers’ perspective, also provide some promising implications for future study and actions to facilitate teachers’ use of OER. However, the study has some limitations. For example, our results may be skewed because only subjective, self-reported survey data from teachers were collected and analyzed. This potential bias could be minimized through a follow-up study to collect, analyze, and triangulate multiple types of data, such as classroom observations of teachers’ OER adoption and interviews with stakeholders (such as policy makers, school leaders, OER developers, and teachers). Moreover, this is a snapshot of teachers’ attitudes at the time of the study. The OER field is changing rapidly as culture, the economy, and technology evolve. Therefore, a longitudinal study of teachers’ use of OER may provide more nuanced insights into their responses to OER adoption in China. Despite these limitations, the value of the study is that it helps us shape future research and practices that can encourage OER adoption in Chinese K-12 education. For example, the content and pedagogical quality of OER for teachers’ instruction should be addressed. Attention should also be given to building systematic school cultural support for OER. From the perspective of teachers, methods for enhancing their self-efficacy with OER should be studied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and L.-H.W.; methodology, H.C. and H.D.; software, H.C. and X.L.; validation, H.C. and H.D.; formal analysis, H.C. and H.D.; investigation, H.C.; resources, H.C.; data curation, H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C., H.D. and X.L.; writing—review and editing, L.-H.W.; visualization, H.C. and X.L.; supervision, L.-H.W.; project administration, H.C. and L.-H.W.; funding acquisition, H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Fund of China for Young Scholars in Education, named the strategy and governance study of teacher’s community of practice within the human-machine interaction scenarios on teacher professional development, grant number CCA220318.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Jiangnan University (protocol code JNU20221201IRB02 and date of approval was 15 December 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the first author. For such inquiries, please contact

caihy@jiangnan.edu.cn.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the anonymous referees for their constructive comments and helpful suggestions to improve the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, J.; Tigelaara, D.E.; Admiraala, W. Connecting rural schools to quality education: Rural teachers’ use of digital educa-tional resources. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomgren, C. OER awareness and use: The affinity between higher education and K-12. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 2018, 19, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Liu, D.; Tlili, A.; Knyazeva, S.; Chang, T.W.; Zhang, X.; Burgos, D.; Jemni, M.; Zhang, M.; Zhuang, R.; et al. Guidance on Open Educational Practices during School Closures: Utilizing OER under COVID-19 Pandemic in line with UNESCO OER Recommendation; Smart Learning Institute of Beijing Normal University: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on Open Educational Resources. 2019. Available online: http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=49556&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- Kreijns, K.; Van Acker, F.; Vermeulen, M.; Van Buuren, H. What stimulates teachers to integrate ICT in their pedagogical practices? The use of digital learning materials in education. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamba-Yugsi, M.; Atiaja, L.A.; Luján-Mora, S.; Eguia-Gomez, J.L. Determinants of the Intention to Use MOOCs as a Complementary Tool: An Observational Study of Ecuadorian Teachers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, N.; Wright, N.; Dawes, L.; Kerr, J.; Robertson, A. Co-design for curriculum planning: A model for professional development for high school teachers. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. (Online) 2019, 44, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, M.; Kreijns, K.; Van Buuren, H.; Van Acker, F. The role of transformative leadership, ICT-infrastructure and learning climate in teachers’ use of digital learning materials during their classes. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 48, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, K.I.C.J.M. User-oriented quality for OER: Understanding teachers’ views on re-use, quality, and trust. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2012, 28, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Muhaimin, A.; Habibi, A.; Mukminin, A.; Hadisaputra, P. Science teachers’ integration of digital resources in education: A survey in rural areas of one Indonesian province. Heliyon 2020, 6, 4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yang, X.; Yang, W.; Lu, C.; Li, M. Effects of teacher-and school-level ICT training on teachers’ use of digital education-al resources in rural schools in China: A multilevel moderation model. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 111, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tigelaara, D.E.; Admiraala, W. Rural teachers’ sharing of digital educational resources: From motivation to behavior. Comput. Educ. 2021, 161, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knauder, H.; Koschmieder, C. Individualized student support in primary school teaching: A review of influencing factors using the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 77, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreijns, K.; Vermeulen, M.; van Buuren, H.; Van Acker, F. Does Successful Use of Digital Learning Materials Predict Teachers’ Intention to Use Them Again in the Future? Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 2017, 18, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G.; Valcke, M.; van Braak, J.; Tondeur, J.; Zhu, C. Predicting ICT integration into classroom teaching in Chinese primary schools: Exploring the complex interplay of teacher related variables. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2011, 27, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Braak, J.; Tondeur, J.; Valcke, M. Explaining different types of computer use among primary school teachers. Eur. J. Psy-chol. Educ. 2004, 19, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, L. Examining EFL teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge and the adoption of mobile-assisted language learning: A partial least square approach. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2016, 29, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.J.; Park, S.; Lim, E. Factors influencing preservice teachers’ intention to use technology: TPACK, teacher self-efficacy, and technology acceptance model. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2018, 21, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Q.; Zhao, P.; Lv, X. The connotations and development of digital education resource service. Chin. J. ICT Educ. 2018, 7, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S. Enhancing teaching and learning of science through use of ICT: Methods and materials. Sch. Sci. Rev. 2003, 84, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlinde, R.; van Braak, J.; Dexter, S. ICT policy planning in a context of curriculum reform: Disentanglement of ICT policy domains and artifacts. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, C.H.; Tang, Y. The relationship between technology leadership strategies and effectiveness of school administration: An empirical study. Comput. Educ. 2014, 76, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowski, R. School Culture and School Performance. 2001. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download. (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Miranda, H.P.; Russell, M. Understanding factors associated with teacher directed student use of technology in elementary classrooms: A structural equation modeling approach. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2012, 43, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Recker, M. Not all rubrics are equal: A review of rubrics for evaluating the quality of open educational resources. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 2015, 16, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Peláez, A.; Segarra-Faggioni, V.; Piedra, N.; Tovar, E. A proposal of quality assessment of OER based on emergent technology. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 8–11 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Atenas, J.; Havemann, L. Questions of quality in repositories of open educational resources: A literature review. Res. Learn. Technol. 2014, 22, 20889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Mateo, M.; Maina, M.F.; Guitert, M.; Romero, M. Learner generated content: Quality criteria in online collaborative learning. Eur. Open Dis. e-Learn. 2011, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, K.; Pawlowski, J.; Manouselis, N. Open educational resources repositories literature review-Towards a compre-hensive quality approaches framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjerrouit, S. A conceptual framework for using and evaluating web-based learning resources in school education. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2010, 9, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leacock, T.L.; Nesbit, J.C. A framework for evaluating the quality of multimedia learning resources. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2007, 10, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Lin, Y.J.; Qian, Y. Understanding K-12 teachers’ intention to adopt open educational resources: A mixed methods inquiry. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 2558–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kopcha, T.J. Teachers’ perceptions of the barriers to technology integration and practices with technology unOER situated professional development. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, S.; Kuan, P.Y. The impact of multilevel factors on technology integration: The case of Taiwanese grade 1-9 teachers and schools. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2013, 61, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, F.A.; Lowther, D.L. Factors affecting technology integration in K-12 classrooms: A path model. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2010, 58, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokelainen, P. An empirical assessment of pedagogical usability criteria for digital learning material with elementary school students. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2006, 9, 178–197. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmons, R. OER Quality and Adaptation in K-12: Comparing Teacher Evaluations of Copyright-Restricted, Open, and Open/Adapted Textbooks. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 2015, 16, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S. Open educational resources: Removing barriers from within. Dist. Educ. 2017, 38, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, M.; Van Acker, F.; Kreijns, K.; Van Buuren, H. Does transformational leadership encourage teachers’ use of digital learning materials. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2015, 43, 1006–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Guo, Z. A survey research on principals’ technology leadership. Mod. Dist. Educ. 2013, 5, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.; Jantzi, D. Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2006, 17, 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasinathan, G.; Ranganathan, S. Teacher professional learning communities: A collaborative OER adoption approach in Karnataka, India. In Adoption and impact of OER in the Global South; Hodgkinson-Williams, C., Arinto, P.B., Eds.; CERN Data Centre: Prévessin-Moëns, France, 2017; pp. 499–548. [Google Scholar]

- Vongkulluksn, V.W.; Xie, K.; Bowman, M.A. The role of value on teachers’ internalization of external barriers and external-ization of personal beliefs for classroom technology integration. Comput. Educ. 2018, 118, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, D. Driven by Emotions! The Effect of Attitudes on Intention and Behaviour regarding Open Educational Resources (OER). J. Interact. Med. Educ. 2021, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Q.; Wang, P.; Zhang, J. Supply Mode, Classification Framework and Developmental Strategies of Digital Educational Resources. e-Educ. Res. 2018, 39, 68–74, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Mandinach, E.B.; Jimerson, J.B. Teachers learning how to use data: A synthesis of the issues and what is known. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 60, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Yin, H.; Chen, M. What factors affect teachers’ use of digital educational resources: From the construction and development of educational informationization in china in the intelligent age. e-Educ. Res. 2019, 7, 69–76, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Baas, M.; van der Rijst, R.; Huizinga, T.; van den Berg, E.; Admiraal, W. Would you use them? A qualitative study on teachers’ assessments of open educational resources in higher education. Int. High. Educ. 2022, 54, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.H.D.; Lin, M.F.G.; Shen, W. Understanding Chinese-speaking open courseware users: A case study on user en-gagement in an open courseware portal in Taiwan (Opensource Opencourse Prototype System). Open Learn. J. Open Dist. e-Learn. 2012, 27, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelter, J.; Peel, A.; Bain, C.; Anton, G.; Dabholkar, S.; Horn, M.S.; Wilensky, U. Constructionist co-design: A dual approach to curriculum and professional development. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 1043–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D. A theoretical framework for studying teachers’ curriculum supplementation. Rev. Educ. Res. 2022, 92, 455–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomgren, C.; McPherson, I. Scoping the nascent: An analysis of K-12 OER research 2012–2017. Open Prax. 2018, 10, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, M.; Abramovich, S. Crossing the boundaries through OER adoption: Considering open educational resources (OER) as boundary objects in higher education. Libr. Inform. Sci. Res. 2022, 44, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).