Abstract

Here, the role of business managers in Poland and Germany in creating responsible business was analyzed. The authors examined CSR strategies, challenges in balancing interests and integrating CSR principles with business practices. They emphasize the importance of education and the active involvement of managers in CSR strategies for the company’s long-term benefits. The article uses three key research methods. The first is a review of the Polish and foreign literature, allowing for an understanding of the global context of CSR. The second method is the analysis of CSR reports from Poland and Germany, giving insight into practices and standards in these countries. The third method is research based on a questionnaire survey conducted in Poland and Germany, enabling a direct understanding of the attitudes and practices of managers. Polish companies lean towards sustainable purchasing and training more than their German counterparts, pointing to a nuanced approach to CSR in Poland. Meanwhile, German firms appear more invested in community and environmental programs, highlighting their particular emphasis on certain social and environmental dimensions of business. There is a clear commitment to CSR in both countries, but the varied nature of the initiatives suggests differing cultural or regulatory influences. Enhancing CSR awareness, particularly around sustainability education and emission reductions, emerges as a priority for both nations. The data indicate that managers are crucial in steering CSR practices, with their active involvement often leading to positive outcomes. The study provides an analysis of current CSR landscapes in Poland and Germany.

1. Introduction

The role of managers in shaping a sustainable and socially responsible business has significantly increased in recent years. Today, they are key players who make strategic decisions that directly impact the social and environmental aspects of a company’s operations [1,2]. In the past, managers were mainly seen as initiators of profit and efficiency. However, the modern corporate landscape requires them to also be ambassadors of sustainable development principles and social responsibility [3]. In this context, critical decisions about, for example, the source of raw materials or labor practices are no longer based solely on costs but also on ethical and environmental considerations [4,5].

Let us take a closer look at the key topics discussed in this article. The authors begin with a review of the literature on the role of managers in creating and implementing strategies related to social and environmental responsibility (CSR) in enterprises. These strategies cover a wide range of activities, such as protecting the environment, promoting ethical business practices, developing the local community and safeguarding the well-being of employees [6,7,8]. The authors argue that managers are in a key position to successfully integrate CSR principles into everyday business practices. This task is complicated because it often conflicts with short-term financial goals. Therefore, managers must balance different interests in order to achieve long-term sustainability [7].

The article describes in detail how managers can integrate CSR principles into everyday business practices. Examples include reducing energy consumption, improving working conditions for employees and engaging with the local community. All these activities not only benefit the environment, but also contribute to sustainable business success by creating a positive image of the company among customers and other stakeholders [9,10,11]. The authors emphasize that managers have a key role to play in educating other employees and stakeholders about the benefits of implementing a CSR strategy. Training, workshops, webinars and online courses are just some of the tools that can be used for this purpose [12,13,14,15]. In conclusion, this article is an in-depth study on the growing role of managers in shaping sustainable and socially responsible businesses. This article is definitely a valuable resource for all managers who want to understand how they can effectively integrate CSR principles into their daily business practices.

The authors focus primarily on the role of managers in creating and implementing strategies related to social and environmental responsibility (CSR) in enterprises. These strategies are primarily aimed at achieving a balance between the achievement of business goals and commitments to society and the environment [16,17,18]. When analyzing environmental protection, it can be pointed out that the strategy includes various initiatives, such as reducing energy consumption, minimizing waste, promoting recycling and preserving natural resources. These actions are not only beneficial for the environment, but can also bring financial benefits to companies in the long term by reducing operating costs [19,20,21]. Promoting ethical business practices includes ensuring that the company respects human rights, avoids corruption, provides safe and healthy working conditions, and respects the rights of employees. Managers can promote ethical business practices by developing appropriate policies and procedures and by providing employee training. Developing the local community indicates that enterprises can actively participate in the development of the local community by sponsoring local events, engaging in local social initiatives or running volunteer programs for their employees. This activity is beneficial not only for the community, but also builds a positive image of the company. Securing the welfare of employees includes ensuring fair pay, safe and healthy working conditions, training and development opportunities, as well as understanding and respecting employees’ rights. Employees who feel respected and valued tend to be more engaged and productive [22,23,24,25,26]. In conclusion, the implementation of the CSR strategy is not only a social obligation, but can also bring business benefits. Managers have a key role in shaping and implementing these strategies, and their ability to balance business goals with social and environmental responsibilities will be critical to the future of their businesses.

An analysis of the national and international literature was conducted, aiding in understanding the global perspective of CSR. Next is an examination of CSR reports from Poland and Germany, offering insights into the approaches and standards in both countries. Lastly, there are studies based on a survey carried out in both Poland and Germany, which provide an opportunity to comprehend the perspectives and actions of managers.

2. Materials and Methods

In the article, “Social and ecological responsibility of a manager on the example of small and medium-sized enterprises from Poland and Germany”, various research methods were used to present a comprehensive picture of the problem.

The authors conducted an in-depth review of both the Polish and foreign literature in order to understand the current state of knowledge about the role of a manager in CSR. Scientific articles, industry publications and case studies were analyzed to identify key concepts, theories and methods related to social and environmental responsibility in businesses. The latest CSR reports from Poland and Germany have been analyzed. These documents provided up-to-date data on CSR practices in various industries and enterprises in both countries, offering a real insight into the activities of enterprises in the field of social and environmental responsibility. In order to understand how managers actually implement and perceive CSR strategies, a study based on a survey questionnaire was conducted in Poland and Germany. This study took into account responses from different levels of management and different industries, which allowed us to understand cultural, industry and individual differences in the approach to CSR.

2.1. Review of the Literature

These complex research methods enabled the authors to present a holistic picture of the manager’s role in creating a sustainable and socially responsible business, taking into account the specificity of both Poland and Germany. As a result, the article provides a valuable contribution to the theory and practice of CSR management, offering practical guidance for managers and decision-makers in both countries.

In recent decades, due to the growing social and environmental awareness, the concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become a key aspect of the strategy and operations of many companies. Consumers, employees, investors and other stakeholders expect from organizations not only financial profits, but also a positive impact on society and the environment. In this context, CSR is seen as the commitment of companies to voluntary activities that exceed legal requirements in order to manage the impact of their activities on society and the environment [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Managing the company’s resources, that is, deciding where and how these resources will be used, is one of the most important duties of a manager. In this context, managers are key actors in creating a sustainable and socially responsible business because they are responsible for setting the direction of their companies and implementing CSR strategies [34,35].

Managers have the opportunity to implement CSR practices in various ways, depending on the specifics of their company. They can do this, for example, by introducing eco-innovations, promoting ethical business practices, introducing human resources strategies focused on sustainable development and by engaging in social activities in their community [36,37,38]. Nevertheless, there are many challenges to implementing a CSR strategy that managers must overcome. For example, managers often face the difficulty of balancing short-term financial goals with long-term social and environmental goals. In addition, managers must also find a way to effectively communicate the benefits of CSR both internally and externally so that stakeholders can appreciate the value of these activities [39,40,41,42,43,44]. Managers play a key role in creating a sustainable and socially responsible business by implementing and managing CSR strategies. Therefore, it is essential that managers have the appropriate competences and knowledge about CSR in order to successfully transform their companies in a way that will benefit the company, as well as society and the environment.

2.2. The Role of the Manager in Creating a Sustainable and Socially Responsible Business: The Perspective of Poland and Germany

Poland and Germany, which are important players in the European business scene, are also experiencing the impact of CSR trends. In both these countries, managers play a key role in creating a sustainable and socially responsible business [45,46,47,48].

In Poland, although the concept of CSR is relatively new, managers are increasingly recognizing the importance of a sustainable and socially responsible business. According to the survey, 80% of Polish respondents reported that their organizations have implemented CSR practices, and 65% believe that the long-term benefits of CSR outweigh the short-term costs. Polish managers often focus on internal CSR education, with 63% of respondents reporting that their organizations conduct educational activities on this topic.

In Germany, where CSR is more widespread and established, managers also play a key role in promoting social and environmental responsibility. As many as 90% of German respondents reported that their organizations have implemented CSR practices, and 75% believe that the long-term benefits of CSR outweigh the short-term costs. German managers often use webinars and online courses for CSR education, with 84% of respondents reporting CSR education activities in their organizations. It can be pointed out that in Poland, as in Germany, managers play a key role in promoting and implementing CSR strategies in their organizations. Through their active involvement and leadership, these companies are able to transform their business practices in a way that benefits not only companies but also society and the environment [49,50,51,52].

2.3. The Importance of the Manager’s Role in CSR Strategies in Poland and Germany

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a practice where companies voluntarily incorporate social and environmental aspects into their activities and interactions with stakeholders. CSR has become an important element of strategic management in many companies around the world, including Poland and Germany. Managers play a key role in CSR strategies, shaping and introducing responsible business practices [53,54,55,56]. According to the literature on CSR, managers have a key role in CSR strategies, shaping the culture of the organization and encouraging the involvement of all employees [57,58,59,60]. CSR guidelines and strategies are often developed at the highest levels of management, and managers are responsible for their implementation [61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

In Poland and Germany, managers play an important role in building and maintaining the company’s reputation as socially responsible [68,69,70,71,72]. Managers in these countries often emphasize the need for sustainable development and social inclusion, both inside and outside the company [73]. In Poland, managers face unique challenges and opportunities in the context of CSR. Given the transformations that the country has undergone since the fall of communism, managers must balance new economic opportunities and maintaining social and ecological responsibility [74,75,76,77,78]. One of the main areas in which managers in Poland focus their CSR activities is equality and diversity. Many companies are implementing strategies to promote gender equality and diversity at all levels of the organization [79,80,81,82,83,84]. In addition, companies in Poland are increasingly involved in environmental protection activities, and managers play a key role in the implementation of these initiatives. For example, many managers implement strategies to reduce the company’s CO2 emissions [85].

In Germany, known for its long industrial tradition and innovation, managers play a key role in guiding companies towards sustainability [14]. CSR activities in Germany often focus on environmental aspects such as energy efficiency and the reduction of CO2 emissions [86]. German managers also focus on innovation in the context of CSR. For example, many managers are involved in developing products and services that not only generate profit but also contribute to solving social and environmental problems [87,88,89]. Both countries show different approaches to CSR, and the role of managers in promoting and implementing these initiatives is crucial.

2.4. Conflict between Short-Term Financial Goals and Long-Term CSR Goals

A key challenge for managers is understanding and managing the often-occurring conflict between short-term financial goals and long-term CSR goals. Organizations are often judged by their short-term financial performance. Shareholders and investors expect regular returns, and managers are often under pressure to meet these expectations. As such, there may be situations where investments in CSR initiatives that yield long-term benefits may be overlooked in favor of activities that yield faster returns [90,91,92]. The manager may decide not to invest in renewable energy, which brings environmental benefits but requires significant upfront costs and a longer payback time. Instead, the manager may choose to continue using cheaper energy sources that bring quick savings but are bad for the environment.

This challenge can be overcome by introducing more balanced evaluation models that take into account both the short-term and long-term effects of business decisions. Managers may also seek to better communicate the long-term benefits of CSR to stakeholders such as shareholders, employees and the local community [93,94,95].

In Poland, the conflict between short-term financial goals and long-term CSR goals is particularly pronounced. Polish companies, especially those that have recently transitioned from a planned economy to a market economy, may feel under intense pressure to focus on short-term financial results. Managers may therefore struggle to balance these expectations with the long-term benefits of CSR [96,97,98,99]. The challenge is to understand that while CSR activities may have an initial cost, they can bring financial benefits in the long run; for example, by improving the company’s reputation, increasing employee engagement or building better relationships with the local community [100].

German companies, which have long been obliged to comply with strict environmental and social regulations, are often more focused on the long-term aspect of CSR. Nevertheless, managers of German companies also struggle with the conflict between short-term financial goals and long-term CSR goals [101,102]. Managers must therefore balance the pressure to make quick profits with investments in long-term CSR initiatives, such as the development of sustainable products or investments in renewable energy [102,103,104,105].

2.5. Balancing the Interests of Various Stakeholders

In Poland, managers face the challenge of balancing the interests of various stakeholders—including employees, customers, suppliers, local communities and shareholders—when implementing a CSR strategy. For example, a company may choose to increase employee compensation, which may improve employee engagement and satisfaction, but it may also lead to increased costs that may negatively impact short-term financial performance and shareholder satisfaction [106,107]. Another challenge is communicating the benefits of CSR activities to various stakeholder groups. For example, environmental measures may be attractive to younger consumers but may not be as important to older customers or suppliers [108,109].

As in Poland, managers in Germany must balance the interests of various stakeholder groups when making decisions regarding CSR. Nevertheless, in the German context, there is a strong tradition of stakeholder involvement, especially employees, in company management decisions. Even so, balancing these interests is not easy. For example, investments in green technologies can be viewed positively by the local community and consumers, but they can also lead to increased costs that are a burden for shareholders. Similarly, measures to increase employee welfare, such as better working conditions or training, can increase costs and affect short-term bottom line [110,111].

In Poland, managers are confronted with the challenge of sustainable management of the interests of various stakeholders—from employees, through suppliers, customers, to the local community and shareholders. All this takes place in the context of implementing CSR-related strategies [112,113]. For example, a decision to increase employees’ salaries may bring benefits in the form of increasing their commitment and job satisfaction, but at the same time it may lead to an increase in costs that may negatively affect the company’s short-term financial results and shareholder satisfaction [114,115]. In addition, Polish managers must effectively communicate the benefits of CSR activities to various stakeholder groups, which is also a major challenge. Green activities may attract younger consumers, but may not be as important to older customers or suppliers [116,117].

In Germany, as in Poland, managers are obliged to take into account the interests of various stakeholder groups when making decisions related to CSR. German companies have a long tradition of involving stakeholders, especially employees, in decision-making processes. However, balancing these interests is not a simple task. Investments in environmentally friendly technologies may be well received by the local community and customers, but at the same time they may lead to increased costs for shareholders. On the other hand, measures aimed at increasing the well-being of employees, such as improving working conditions or organizing training, can increase costs and affect short-term financial results [118,119,120].

3. Examples of CSR Activities

In Poland, many companies have taken steps to integrate CSR principles with business practices. These activities include a number of activities such as introducing eco-innovation, increasing corporate transparency, investing in employee welfare and involvement in social activities [121]. For example, the cosmetics company Inglot, based in Przemyśl, applied CSR in its business practices by investing in the production of cosmetics free of harmful substances and supporting local social initiatives [122,123,124,125].

German companies also strive to integrate CSR principles into their business practices. A number of companies take actions for sustainable development, increasing diversity and equality in the workplace, as well as social involvement [126,127,128]. For example, the German automotive company BMW has been investing in the development and production of electric and hybrid cars for years as part of its commitment to sustainable development. The company also implements a number of social and educational programs aimed at young people [129,130,131,132]. Examples of CSR activities are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of CSR activities.

The analysis of activities in the field of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in Poland and Germany shows that companies from both countries are actively involved in social and pro-ecological activities. In Poland, there are various social and pro-ecological initiatives implemented by companies from various sectors. The “Biedronka for Health” and “Green PGE” programs are good examples of companies that pay attention to consumer health and the environment. Other companies, such as Allegro and PKO Bank Polski, focus on supporting local communities and financing various social projects. The IKEA company, known worldwide for the production of furniture, has taken a number of actions to protect the environment. It can be seen that in Poland, there are a number of initiatives aimed at combining business with social ethics and environmental protection.

The same is true in Germany. Companies such as BMW and Siemens are investing in sustainable transport technologies and sustainable development. Deutsche Bank develops community and sustainable investment programs. DHL and Deutsche Post are investing in sustainable transport and logistics, while companies such as Aldi, BASF and Adidas are focusing on sustainable food production, chemicals and fashion. These examples show that a manager’s social and environmental responsibility is not only an ethical imperative, but also a way to build relationships with consumers and local communities, improve the company’s reputation and long-term sustainable business success. All this translates into benefits for all stakeholders, including employees, consumers, local communities and the environment.

Benefits of Integrating CSR with Business Practices Based on Poland and Germany

The integration of corporate social responsibility (CSR) with business practices brings many benefits. Table 2 provides examples of benefits for both Poland and Germany:

Table 2.

Benefits of integrating CSR with business practices based on countries: Poland and Germany.

The integration of corporate social responsibility (CSR) with business practices positively affects the reputation of companies, which is observed in Poland and Germany. For example, GrupaŻywiec in Poland and BMW in Germany have improved their reputations thanks to initiatives related to recycling and the development of electric cars. The implementation of CSR practices can contribute to improving the competitiveness of companies. Examples of such activities include the introduction of a line of ecological products by Lidl in Poland and conducting training courses on social and environmental responsibility by Deutsche Bank in Germany. Companies that demonstrate social and ecological responsibility attract younger talent, as shown by the examples of PKO Bank Polski in Poland and Adidas in Germany. Companies engaging in CSR activities gain greater customer loyalty, which is visible on the examples of Orange in Poland and Aldi in Germany. CSR initiatives can lead to significant savings, as shown by the example of CCC in Poland, which promotes ecological products, and Lufthansa in Germany, investing in sustainable aviation technologies. CSR practices can stimulate innovation, as shown by the example of Allegro in Poland, which promotes the sale of used products, and Siemens in Germany, which offers products for efficient energy management.

4. Results

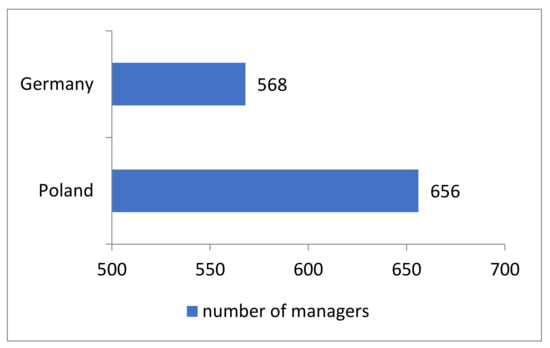

Figure 1 shows the number of managers who participated in the study from Poland and Germany in order to understand the scale and scope of our analysis.

Figure 1.

Number of managers participating in the study. Source: own study.

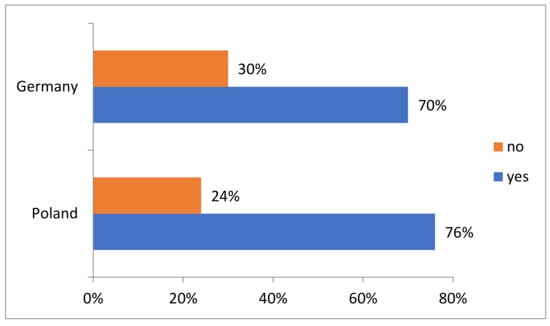

Figure 2 is presented below, showing the percentage of companies that have a formal CSR strategy. We will compare data from Poland and Germany, which will allow us to understand how many companies in these countries have formally integrated CSR into their business strategy.

Figure 2.

Enterprises with a formal CSR strategy implemented in Poland and Germany. Source: own study.

It turns out that in Poland, 500 out of 656 companies, which is 76%, confirmed that they have a formal CSR strategy. Meanwhile, 156 companies (24%) answered in the negative. In Germany, out of 568 companies, 400 (70%) said they had a formal CSR strategy, while 168 companies (30%) said they had no such strategy. It can be seen that a larger percentage of companies in Poland, compared to Germany, have a formal CSR strategy. This may suggest that Polish companies are more involved in corporate social responsibility practices, or simply formalize their strategies in this area more often.

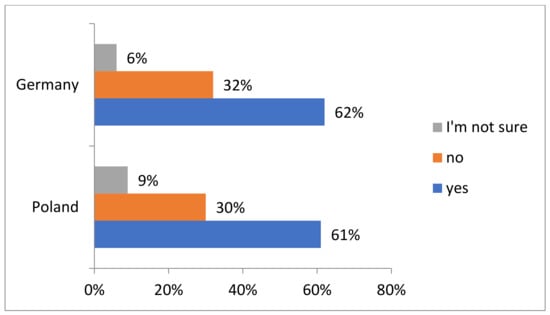

The results shown in Figure 3 indicate that integration suggests that companies do not treat CSR as an additional, separate element, but as a key component of their activities, influencing many aspects of their work, from making business decisions to interacting with stakeholders.

Figure 3.

CSR integration with major business practices in Poland and Germany. Source: own study.

In Poland, 400 out of 656 companies, which is 61%, confirmed that they had integrated CSR with their main business practices. On the other hand, 200 companies (30%) answered that they had not integrated CSR into their main business practices, and 56 companies (9%) were not sure.

In Germany, out of 568 companies, 350 (62%) said they had integrated CSR into their main business practices, while 180 companies (32%) said they had not. In addition, 38 companies (6%) are not sure whether they have integrated CSR into their main business practices.

It can be seen that in both countries the majority of companies have integrated CSR into their main business practices, which shows that companies are beginning to see CSR not only as a valuable addition, but as an integral part of their business model [189,190,191]. Nevertheless, there are still a number of companies that have not made such an integration, suggesting that CSR may not yet be widely understood or a priority in all companies. In addition, there are a number of companies that are uncertain about their CSR integration status, which may indicate a need for better education and communication about what this means and what benefits it can bring.

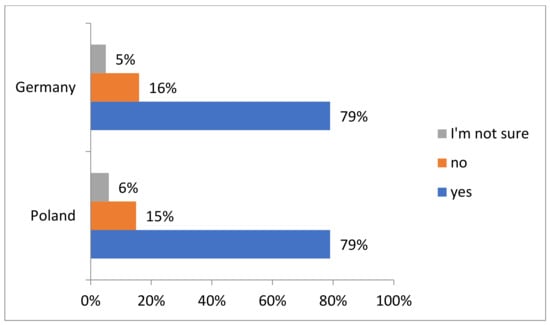

The results shown in Figure 4 indicate that data concern the answers of companies to the question of whether they are familiar with the challenges related to corporate social responsibility (CSR) for managers. These challenges may include aspects such as understanding and applying CSR standards, managing the interests of different stakeholder groups, integrating CSR into business and measuring the impact of CSR activities.

Figure 4.

The level of familiarization of managers with the challenges related to CSR in Poland and Germany. Source: own study.

In Poland, 520 out of 656 companies, which is 79%, confirmed that they are familiar with the challenges related to CSR for managers. On the other hand, 100 companies (15%) responded that they were not familiar with it and 36 companies (6%) were not sure.

In Germany, out of 568 companies, 450 (79%) said they were familiar with CSR challenges for managers, while 90 companies (16%) said they were not familiar with it. In addition, 28 companies (5%) are unsure whether they are familiar with these challenges.

In general, most companies in both countries are familiar with the CSR challenges for managers. However, there is a group of companies that are not familiar with it, which may indicate the need for further education and understanding in the field of CSR. In addition, a certain percentage of companies are not sure whether they are familiar with these challenges, which may indicate uncertainty or a lack of full understanding of how CSR can influence management practices.

CSR education may include, for example, training, workshops, internal communication and other forms of educating employees about what CSR is, why it is important, and what the company’s specific CSR activities and commitments are.

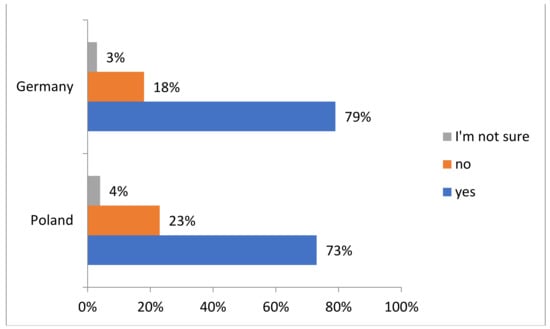

The results in Figure 5 indicate that in Poland, 480 out of 656 companies, which is 73%, confirmed that they educate their employees on CSR. On the other hand, 150 companies (23%) replied that they did not provide such education, and 26 companies (4%) were not sure.

Figure 5.

Companies educating their employees on CSR in Poland and Germany. Source: own study.

The results in Figure 5 indicate that in Germany, out of 568 companies, 450 (79%) stated that they educate their employees on CSR, while 100 companies (18%) replied that they did not provide such education. Moreover, 18 companies (3%) are not sure whether they educate their employees about CSR.

In both countries, most companies educate their employees about CSR. Nevertheless, there are a number of companies that do not provide such education, which may indicate the need for further action in this area. In addition, there are a number of companies that are not sure whether they provide such education, which may indicate the need for better communication and evaluation of educational activities.

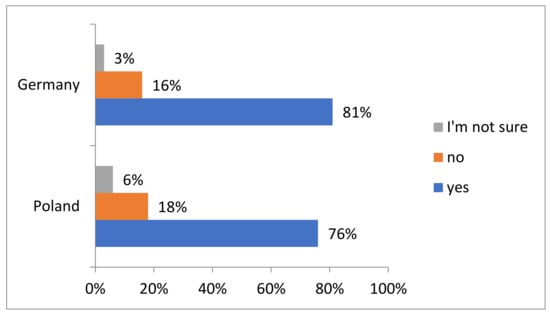

The data concern companies’ answers to the question whether managers play a role in corporate social responsibility (CSR) education in the company. Managers can play a key role in CSR education; for example, by providing training, communicating the company’s CSR policy and goals or modeling appropriate behavior.

The results in Figure 6 indicate that in Poland, 500 out of 656 companies, which is 76%, confirmed that managers play a role in CSR education. On the other hand, 120 companies (18%) answered that managers do not play such a role and 36 companies (6%) are not sure.

Figure 6.

Managers playing a role in CSR education in companies in Poland and Germany. Source: own study.

The results in Figure 6 indicate that in Germany, out of 568 companies, 460 (81%) stated that managers play a role in CSR education, while 90 companies (16%) answered that managers do not play such a role. Moreover, 18 companies (3%) are not sure whether managers play a role in CSR education.

Most companies in both countries confirmed that managers play a role in CSR education. Nevertheless, there are a number of companies that have stated that managers do not play such a role, which may indicate different approaches to CSR education. In addition, there are a number of companies that are not sure whether managers have a role in CSR education, which may indicate ambiguity about the role of managers in this matter.

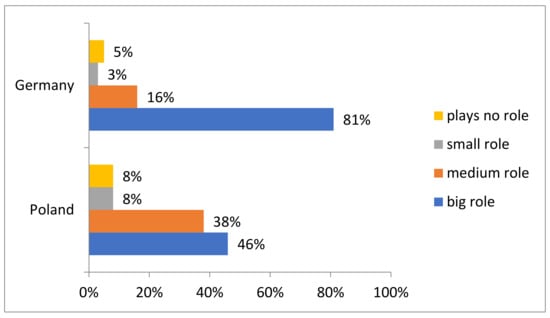

The data in Figure 7 refer to the role that managers play in promoting and implementing the corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategy in the company. This role may include, for example, setting the direction of the CSR strategy, coordinating CSR activities, promoting the value of CSR among employees and making decisions related to CSR. In Poland, 300 out of 656 companies, which is 46%, believe that managers play an important role in promoting and implementing CSR strategies. A total of 250 companies (38%) believe that managers play a medium role, 50 companies (8%) believe that they play a small role and 53 companies (8%) believe that managers do not play a role. In Germany, out of 568 companies, 280 (49%) think managers play a big role, 220 companies (39%) think they play a medium role, 40 companies (7%) think they play a small role and 28 companies (5%) believe that managers do not play a role. Most companies in both countries believe that managers play a large or medium role in promoting and implementing CSR strategies.

Figure 7.

The role played by managers in promoting and implementing CSR strategies in companies in Poland and Germany. Source: own study.

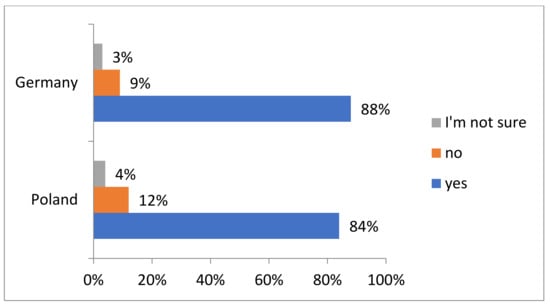

The data in Figure 8 concern the companies’ answers to the question whether they experienced the benefits of the active involvement of managers in corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies. These benefits may include, for example, improving the company’s reputation, increasing employee engagement, improving relationships with customers and suppliers or achieving sustainability goals. In Poland, 550 out of 656 companies, which is 84%, confirmed that they experienced the benefits of the active involvement of managers in CSR strategies. On the other hand, 80 companies (12%) have not experienced such benefits and 26 companies (4%) are not sure. In Germany, out of 568 companies, 500 (88%) confirmed that they had experienced benefits, while 50 companies (9%) had not experienced benefits. In addition, 18 companies (3%) are unsure whether they have experienced benefits.

Figure 8.

Companies experiencing the benefits of active involvement of managers in CSR strategies. Source: own study.

Most companies in both countries have experienced the benefits of managers’ active involvement in CSR strategies. However, there are a number of companies that have not experienced such benefits, which may indicate different experiences of managers’ involvement in CSR strategies. In addition, there are a number of companies that are uncertain whether they have experienced benefits, which may indicate confusion about the impact of managerial involvement on CSR benefits.

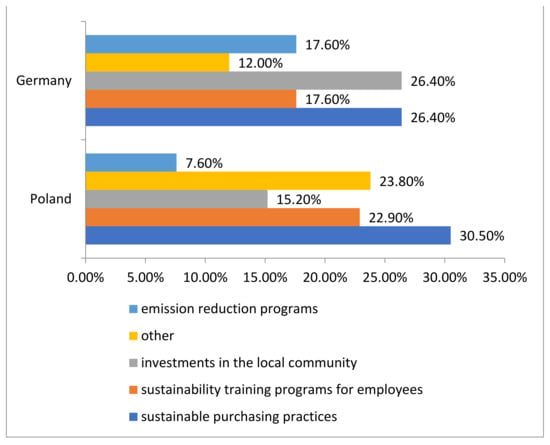

It should be noted that in Poland (in Figure 9 data based on a sample of 656 companies):

Figure 9.

CSR activities undertaken by enterprises in Poland and Germany. Source: own study.

- A total of 30.5% (200 out of 656) of companies have adopted sustainable purchasing practices that take into account environmental, social and ethical aspects.

- A total of 22.9% (150 out of 656) of companies organized training programs for employees on sustainability.

- A total of 15.2% (100 out of 656) of companies invested in the local community.

- A total of 7.6% (50 out of 656) of companies have undertaken emission reduction programs.

- A total of 23.8% (156 out of 656) of companies took other CSR activities.

In turn, in Germany (in Figure 9 data based on a sample of 568 companies):

- A total of 26.4% (150 out of 568) of companies have adopted sustainable purchasing practices.

- A total of 17.6% (100 out of 568) of companies organized training programs for employees on sustainability.

- A total of 26.4% (150 out of 568) of companies invested in the local community.

- A total of 17.6% (100 out of 568) of companies have undertaken emission reduction programs.

- A total of 12% (68 out of 568) of companies have undertaken other CSR activities.

Comparison of Poland and Germany: Sustainable purchasing practices are more popular in Poland (30.5%) compared to Germany (26.4%). Sustainability training programs are more common in Poland (22.9%) than in Germany (17.6%). Investments in the local community are equally popular in Poland (15.2%) and Germany (26.4%). Emission reduction programs are less popular in Poland (7.6%) than in Germany (17.6%). Other CSR activities are much more common in Poland (23.8%) than in Germany (12%).

In conclusion, both countries show a high commitment to CSR, but they differ in terms of specific activities. Polish companies seem to focus more on sustainable purchasing practices and employee training, while German companies seem more focused on investing in the local community and reducing emissions. “Other” CSR activities are also much more common in Poland, which may suggest that Polish companies undertake a number of various CSR initiatives that were not directly mentioned in this survey.

5. Discussion

It should be emphasized that in Poland, the most popular CSR activity is the adoption of sustainable purchasing practices, which are familiar to 30.5% of companies. These actions may include, for example, giving preference to suppliers that meet certain environmental, social or ethical standards. The second most popular activity is organizing training programs for employees on sustainability, which is implemented by 22.9% of companies. A smaller but significant percentage of companies (15.2%) invest in the local community, and 7.6% of companies have undertaken emission reduction programs. The category “other activities in the field of CSR” includes various initiatives that 23.8% of companies became familiar with. In Germany, investments in the local community and sustainable purchasing practices are the most popular, with 26.4% of companies each. In total, 17.6% of companies organized sustainability training programs for employees, and the same percentage undertook emission reduction programs. A total of 12% of companies fall into the “other” category.

Comparing the two countries, we notice several significant differences. Sustainable purchasing practices are slightly more popular in Poland (30.5%) compared to Germany (26.4%). The same is true for sustainability training programs, which are more common in Poland (22.9%) than in Germany (17.6%). However, Germany outperforms Poland in investments in the local community (26.4% compared to 15.2% in Poland) and emission reduction programs (17.6% compared to 7.6% in Poland). It is also worth noting that “other” CSR activities are much more common in Poland (23.8% compared to 12% in Germany). This may suggest that Polish companies are more innovative or experimental in their approach to CSR, or that they are taking actions that were not directly included in this survey.

Managers play a key role in creating sustainable and socially responsible companies, both in Poland and Germany.

First, managers are responsible for establishing and enforcing policies that aim to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. In practice, this means introducing and enforcing practices related to energy saving, reducing the emission of harmful substances into the environment, the responsible use of resources, recycling, as well as counteracting unethical business practices.

In Germany, where sustainability issues have long been at the forefront, managers are required to introduce innovative solutions that reduce the environmental impact of their companies. For example, technologies that help companies use less energy, produce less waste or use renewable energy sources. In Poland, where issues of sustainable development are becoming more and more important, managers must pay special attention to reducing the negative impact of their companies on the environment. In practice, this means they must implement practices that comply with the law, that contribute to protecting the environment and that help companies achieve their business goals without harming the planet. Secondly, managers play a key role in promoting corporate social responsibility (CSR) in their companies. This means that they must pay attention to the social good, not just profit [192,193,194]. In practice, this can mean creating jobs, paying fair wages, ensuring the health and safety of employees, implementing gender equality policies, and doing business in a way that benefits local communities. Both in Germany and in Poland, managers play a key role in promoting and implementing CSR principles. Despite the cultural and economic differences between the two countries, the idea of corporate social responsibility is equally important and translates into a number of similar activities undertaken by managers in both countries.

In conclusion, the role of a manager in creating a sustainable and socially responsible business is extremely important, regardless of the country in which the company operates. Managers are responsible for shaping the organizational culture and practices that influence the way the company affects the environment and society. Both in Poland and Germany, managers must be leaders who promote sustainable development and corporate social responsibility in their companies.

6. Conclusions

Polish companies are more likely to implement sustainable purchasing practices and training programs on sustainability compared to German companies. This may indicate a stronger commitment to CSR principles in these aspects of business in Poland. German companies are more likely to invest in the local community and implement emission reduction programs than Polish companies. This may indicate a greater commitment of German companies to improve the social and environmental aspects of their operations. In Poland, many more companies undertake “other” activities in the field of CSR, which may suggest greater innovation or flexibility in their approach to CSR. It may also indicate that Polish companies are taking actions that were not directly included in this survey. There is a noticeable commitment to CSR in both countries, but differences in the types of activities undertaken may indicate cultural, regulatory, economic or social differences between Poland and Germany.

Overall, the results indicate the need to further promote and develop CSR practices in companies, both in Poland and Germany. Of particular importance may be actions aimed at raising awareness and educating employees about sustainability and promoting investment in the local community and reducing emissions. These conclusions highlight the importance of the individual interpretation and application of CSR practices by companies. Therefore, it is worthwhile for companies to individually consider their CSR strategies, taking into account their unique contexts, business goals and impact on the community. It is also worth noting that while these data provide valuable information on the current state of CSR in Poland and Germany, they are limited to a specific sample of companies. For a fuller understanding of CSR in these countries, it would be beneficial to carry out further research, taking into account different sectors and sizes of companies. In addition, although these data show some trends, CSR is a dynamic field that is constantly evolving. Therefore, companies should regularly evaluate and update their CSR strategies to keep up with changing social expectations, regulations and best practices in the field of sustainable business.

6.1. The Importance of the Manager’s Role in CSR Strategies

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is gaining importance around the world, and managers play a key role in promoting and implementing CSR practices in their organizations. In the context of Poland and Germany, two dynamically developing European economies, this role of the manager is becoming more and more visible and important. In Poland, where the approach to CSR is still relatively young, managers play an increasingly important role in the implementation of CSR strategies. According to a survey conducted among Polish managers, 80% of respondents reported that their organizations have implemented CSR practices. Moreover, 65% of respondents believe that the long-term benefits of CSR outweigh the short-term costs. A tendency to use internal CSR education is also noticeable, which emphasizes the importance of shaping the awareness and involvement of staff in CSR activities. In Germany, CSR is a more developed and established concept. Almost 90% of German managers reported that their organizations implement CSR practices, and 75% of respondents confirm that the long-term benefits of CSR exceed the short-term costs. German managers, like their Polish colleagues, place great emphasis on education, but often use digital technologies such as webinars and online courses for this purpose. There is a definite shift towards digital learning and remote education.

It should be emphasized that in Poland, as in Germany, managers play an important role in creating a sustainable and socially responsible business. Leadership, commitment and education are the main tools that managers in both countries use to promote CSR practices in their organizations. Without their leadership and commitment, CSR practices may not bring the expected results, both for the company and for the communities in which they operate. Corporate social responsibility is important: most companies in both countries reported having a formal CSR strategy. This indicates the growing importance of CSR in the business strategies of companies that recognize the need to be socially responsible. A higher percentage of companies in Poland have a formal CSR strategy compared to companies in Germany. This may suggest that Polish companies may be more involved in corporate social responsibility, or that they are more willing to formalize their CSR strategies. There is a group of companies, both in Poland and Germany, that do not have a formal CSR strategy. This may indicate the need for further education and promotion of the importance of CSR among enterprises. It may also suggest that some companies may conduct socially responsible activities, but do not formalize them as part of the official strategy. The difference in the percentage of companies with CSR strategies between the two countries may point to interesting directions for further research.

However, it is important to remember that the answers to this question alone do not provide the full picture. It would be useful to check how exactly these CSR strategies are implemented and how effective they are in practice. Most companies, both in Poland and Germany, have integrated corporate social responsibility into their main business practices. This suggests that CSR is no longer seen as just an add-on or a ‘nice gesture’, but as an essential element of business strategy. Even though most companies have integrated CSR into their business practices, there is still a large proportion of companies that have not. This suggests that there is a need to further raise awareness of the importance of CSR and the benefits of integrating it into mainstream business practices. There is a group of companies that are not sure whether they have integrated CSR into their main business practices. This may indicate some misunderstanding of what CSR integration really means, suggesting that there is a need for further education in this field.

6.2. Social and Environmental Responsibility of Companies from Poland and Germany

Both Poland and Germany display similar trends regarding CSR integration, highlighting its significance for firms in these nations. Although the majority of companies are cognizant of the challenges tied to CSR, a certain proportion in both countries remains unfamiliar with them, indicating the need for enhanced education, particularly concerning practical aspects and implementation challenges. A percentage of businesses are uncertain about their understanding of CSR challenges, possibly indicating ambiguity regarding the practical implications of CSR.

The overall knowledge about CSR challenges is comparable in both countries, suggesting a relatively substantial level of comprehension and education in CSR matters. Most companies in Poland and Germany educate their employees about CSR, signifying the importance they place on informing and engaging their workforce about corporate social responsibility. Yet, a significant portion does not, pointing towards the need for further CSR education in the business community. In both countries, a minor fraction of companies are unsure about their approach to CSR education, which might reflect unclear definitions of “CSR education” or the absence of a systematic educational strategy.

More companies in Germany than in Poland conduct education on CSR. This may suggest that German companies may be more involved in CSR issues, or may have better resources to conduct such education. Most companies in Poland and Germany agree that managers play a role in CSR education. This indicates the key role of business leaders in promoting and implementing CSR practices. Some companies report that their managers do not play a role in CSR education. This may indicate differences in the approach to CSR and education in this field in different companies, and perhaps also different levels of commitment to CSR. In both countries, there is a small percentage of companies that are unsure whether their managers play a role in CSR education. This may suggest some ambiguity about the role of managers in this process, and perhaps also the lack of a coordinated or systematic approach to CSR education. Germany has a slightly higher percentage of companies where managers play a role in CSR education, compared to Poland. This may suggest that managers in Germany may be more involved in CSR issues, or may have better resources to conduct such education. Most companies in Poland and Germany believe that managers play a large or medium role in promoting and implementing CSR strategies. This indicates that business leaders are crucial for the effective implementation of the CSR strategy. There is some diversity in the perception of the role of managers in CSR, which indicates different approaches to CSR implementation. Some companies believe that managers play only a small or no role, which may suggest that in these companies CSR may be perceived as less strategic or that responsibility for CSR may be dispersed among many different people or departments. Germany has a slightly higher percentage of companies in which managers play a large role in promoting and implementing CSR strategies, compared to Poland. This may suggest that managers in Germany may be more involved in CSR issues, or may have better resources to conduct such education. While these data provide valuable information about the perceived role of managers in CSR strategy, they do not provide a complete picture. For example, we do not know what the specific actions managers take in their role are, or how effective they are in their role. These aspects may require further investigation. Most companies, both in Poland and Germany, report benefits from the active involvement of managers in CSR strategies. This indicates that business leaders can have a significant impact on the success of a CSR strategy. While most companies have experienced benefits, some companies have not. This may suggest that the effectiveness of managers’ involvement in CSR may depend on many factors, such as, for example, specific actions taken by managers, the company’s culture or the sector in which the company operates.

A number of companies in both countries are not sure whether they have experienced the benefits of managers’ involvement in CSR strategies. This may suggest that the benefits of CSR may be difficult to measure or may require long-term commitment. Germany has a slightly higher percentage of companies that have experienced benefits from the active involvement of managers in CSR strategies, compared to Poland. This may suggest that CSR practices in Germany may be more advanced or more effective. Most companies in both Poland and Germany have a formal CSR strategy, which shows that corporate social responsibility is considered an important issue in both countries.

More than half of the companies in both countries have integrated CSR into their main business practices, which indicates the increasing importance of CSR in the daily operation of companies. Managers play a key role in educating employees about CSR and in promoting and implementing CSR strategies. Most companies have experienced the benefits of managers’ active involvement in CSR strategies, highlighting the value of business leaders in promoting sustainable development. Most companies educate their employees about CSR, which indicates an understanding of the need for broad understanding and the acceptance of CSR throughout the organization. Most of the respondents are familiar with the CSR challenges for managers, which suggests that managers are aware and ready to face the difficulties of CSR implementation. In general comparison, Germany seems to have a slightly greater involvement in CSR issues at the level of managers and a higher percentage of companies that have experienced the benefits of the active involvement of managers in CSR strategies compared to Poland. Polish companies tend to prioritize sustainable purchasing practices and sustainability training more than German firms. This hints at Poland’s stronger dedication to certain facets of CSR.

6.3. CSR as an Integral Component of Business Practices—Comparison between Germany and Poland

Synthetic conclusions are presented below:

- German enterprises show a higher tendency to invest locally and focus on emission reduction than their Polish counterparts, suggesting a deeper commitment to certain social and environmental facets of business.

- Polish businesses frequently engage in diverse CSR activities not categorized in the survey, pointing to potentially greater flexibility or innovation in their CSR approach.

- Both nations display a clear commitment to CSR, but the varied nature of their initiatives could be influenced by cultural, regulatory or social distinctions.

- The data underscore the necessity of bolstering CSR practices and awareness in both countries. Key focal areas could include employee education on sustainability, local community investments and emissions reductions.

- The disparities and commonalities in CSR strategies highlight the need for companies to tailor their CSR approaches to their specific contexts and business objectives.

- While the provided data offer a snapshot of CSR in both countries, a broader study across diverse sectors and business sizes would provide a more comprehensive view.

- CSR is fluid and ever-evolving. Companies need to perpetually assess and recalibrate their CSR strategies in response to changing societal expectations and best practices.

- Managers play a pivotal role in both nations in fostering and enacting CSR practices, emphasizing the necessity of leadership in achieving meaningful CSR outcomes.

- The variance in CSR strategy adoption between Poland and Germany could be an intriguing avenue for further exploration, potentially revealing insights about cultural or regulatory influences.

- While a majority of businesses in both nations have incorporated CSR into their core operations, there is still room for more integration and awareness on its significance.

- Education about CSR is prominent in both countries, but modes of imparting this knowledge differ, pointing to varying approaches or resource availability.

- The data suggest that managers’ involvement in CSR is beneficial, but the degree of benefit might vary based on several factors, including the company culture or operational sector.

From the information provided, it is evident that corporate social responsibility (CSR)) has become an integral component in business practices in both countries. It is particularly noteworthy to see the role managers play in its adoption and implementation. Here is a summarized breakdown and analysis of the information:

- Integration of CSR: Both countries have over 50% of their companies incorporating CSR into their daily business operations. This not only indicates a shift towards sustainable business practices but also underlines the importance of CSR in the modern business environment.

- Role of Managers: Managers serve as the bridge between the higher-level strategic goals and operational-level tasks. Their involvement in educating employees about CSR is pivotal. Given their influence, active participation from them can effectively drive the CSR agenda in a company. The fact that companies are experiencing benefits from such involvement underlines the importance of leadership in CSR initiatives.

- Employee Education: By educating their workforce about CSR, companies are ensuring a holistic understanding and acceptance throughout the organization. When employees, regardless of their positions, understand the importance and goals of CSR, it fosters a culture that supports sustainability and ethical business practices.

- Challenges: The recognition of challenges faced by managers in CSR implementation indicates preparedness. If managers are aware of the hurdles, they are better positioned to navigate them.

Comparison between Germany and Poland:

- Germany: Seems to have a marginally higher engagement at the managerial level in CSR issues and more companies have witnessed the advantages of active managerial involvement. This might indicate a more top-down approach in German companies where leadership takes the initiative in driving CSR goals.

- Poland: The emphasis on sustainable purchasing practices and sustainability training indicates a different approach to CSR. Sustainable purchasing practices can have a domino effect, promoting sustainable practices up and down the supply chain. By emphasizing sustainability training, Polish companies are ensuring that the workforce is equipped with the necessary knowledge to make informed decisions in their roles.

In conclusion, while both countries show significant adoption and appreciation for CSR, their priorities differ slightly. German companies seem to be leveraging their leadership in promoting CSR, whereas Polish firms are emphasizing the specific facets of CSR; namely, sustainable purchasing and training. This divergence in approach reflects cultural, economic and perhaps historical influences on their corporate sectors. It would be interesting to explore how these differences in approach impact the overall effectiveness of CSR initiatives in each country. However, future research will undoubtedly focus on environment, social responsibility, corporate governance (ESG) aspects, as an idea constituting the next stage of CSR. This idea assumes that companies should not only care about their economic interests, because business should bring broadly understood benefits to all stakeholders, local communities and the environment. Only in this way the company ensures sustainable development and stability for itself and the environment in which it is located. All this is the result of the ongoing evolution of the capital market. As a result of these transformations, there was a need for an in-depth analysis not limited to the company’s ability for solvency or cover its own financial liabilities. Entities investing professionally on the capital market began to pay attention to all aspects of a responsible economy, and not only to the business dimension of a single economic entity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; methodology, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; software, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; validation, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; formal analysis, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; investigation, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; resources, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; data curation, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; visualization, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; supervision, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; project administration, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K.; funding acquisition, H.W., I.M., M.G., D.K., R.B., J.B. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Werther, W.B.; Chandler, D. Strategic corporate social responsibility as global brand insurance. Bus. Horiz. 2005, 48, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, M.A.L.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juniarti, J. Does mandatory CSR provide long-term benefits to shareholders? Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 17, 776–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. Business Ethics and Environmental Responsibility: An Empirical Examination of Managerial Strategies. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 73, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Anderson, P.; Becker, H.; Martin, J.; Thomas, L. Balancing Short-term Financial Goals with Long-term CSR Strategy: An Empirical Analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 163, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E. From Theory to Practice: Translating CSR Principles into Business Strategy. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2020, 41, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, L. CSR and its Implementation in Contemporary Business: Managerial Approaches. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2022, 30, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rudnicka, A. CSR—Improving Social Relations in the Company; Wolters Kluwer Business: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. Impact of CSR on Corporate Image: The Role of Sustainable Practices. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A. Effective CSR Practices for Positive Stakeholder Engagement. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 31, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Miciuła, I.; Nowakowska-Grunt, J. Using the AHP method to select an energy supplier for household in Poland. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 159, 2324–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N. Leveraging Webinars for Sustainability Education: A Managerial Perspective. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2022, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, P. Online Courses and Sustainability Education: Insights from Managers. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2022, 31, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- García-Muiña, F.E.; Medina-Salgado, M.S.; Ferrari, A.M.; Cucchi, M. Sustainability transition in Industry 4.0 and Smart Manufacturing with the triple-layered business model canvas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.; Jakeman, M.; Johansson, C. Managing Corporate Sustainability: Role of Managers in Implementing Strategies. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 165, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtaszek, H.; Miciuła, I. Analysis of Factors Giving the Opportunity for Implementation of Innovations on the Example of Manufacturing Enterprises in the Silesian Province. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gupta, R.; Kumar, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Protection. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, M.; Kumar, P.; Ma, Y. The Role of CSR in Achieving Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, J.; Lowe, A.; Ellem, B. Ethical Business Practices and CSR in Organisations. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 159, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.; Chow, T. The Benefits of Implementing Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from the Asian Market. Asian Bus. Manag. 2020, 19, 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.; Singh, P. CSR and Employee Welfare: An Empirical Analysis. Empl. Relat. 2020, 42, 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, H.; Kumar, S.; Tavoni, M. Impact of CSR on Employee Welfare. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H.; Yakovleva, N. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Mining Industry: Exploring Trends in Social and Environmental Disclosure. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 14, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, N.L. Corporation as climate ambassador: Transcending business sector boundaries in a Swedish CSR campaign. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, C.; Pratt, M.; Grant, A.; Dunn, C. Meaningful Work: Connecting Business Ethics and Organization Studies. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 121, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.; Pfitzer, M.; Lee, P. The Ecosystem of Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2022, 94, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, M.; Kaul, D. Exploring the Linkage between Stakeholder Management, CSR and Corporate Reputation. Vikalpa 2020, 45, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, H.; Hayden, F. Incorporating Corporate Social Responsibility into Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Why Companies are Becoming B Corporations. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2022, 96, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, D.; Werther, W. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Stakeholders in a Global Environment. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, A.A.; Shauki, E.R. Socially responsible investment in Malaysia: Behavioral framework in evaluating investors’ decision making process. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 80, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhamme, J.; Grobben, B. The Too-Good-To-Be-True Paradox and the Role of Corporate Social Responsibility Skepticism. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 165, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bondy, K.; Moon, J.; Matten, D. An Institution of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Multi-National Corporations (MNCs): Form and Implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 111, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Creating and Capturing Value: Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility, Resource-Based Theory, and Sustainable Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 2021, 37, 1480–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.; Walker, R. Ethos, logos, pathos: Strategies of persuasion in social/environmental reports. Account. Forum 2022, 36, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Post, C. Measurement Issues in Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility (ECSR): Toward a Transparent, Reliable, and Construct Valid Measure. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 105, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Pirsch, J. A taxonomy of cause-related marketing research: Current findings and future research directions. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2020, 19, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylżanowski, R.; Kazojć, K.; Miciuła, I. Exploring the Link between Energy Efficiency and the Environmental Dimension of Corporate Social Responsibility: A Case Study of International Companies in Poland. Energies 2023, 16, 6080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Carroll, A. Capturing advances in CSR: Developed versus developing country perspectives. Bus. Ethic A Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Q.; Lee, H. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Enhancing Financial Performance: Evidence from Asian and European Retailers. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 149, 4276–4291. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P. Long-Term Impact of CSR on Business Profitability and Survival. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 11, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mustapha, M.A.; Manan, Z.A.; Alwi, S.R.W. Sustainable Green Management System (SGMS)—An integrated approach towards organizational sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 146, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzmueller, M.; Shimshack, J. Economic perspectives on corporate social responsibilities. J. Econ. Lit. 2012, 50, 51–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Effective Communication of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): A Framework. J. Bus. Commun. 2021, 58, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F. Sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation, and business models: Integrative framework and propositions for future research. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, W.M. Aligning Stakeholder Engagement Strategies with CSR Communication. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 118, 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, C.; Stark, A.W. Environmental, social and governance disclosure, integrated reporting, and the accuracy of analyst forecasts. Br. Account. Rev. 2018, 50, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakhathi, A.; le Roux, C.; Davis, A. Sustainability leaders’ influencing strategies for institutionalising organisational change towards corporate sustainability: A strategy-as-practice perspective. J. Chang. Manag. 2019, 19, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miciuła, I.; Miciuła, K. Renewable Energy and Its Financial Aspects as an Element of the Sustainable Development of Poland; Scientific Papers of Wrocław University of Economics No. 330; Wrocław University of Economics: Wrocław, Poland, 2014; pp. 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, D.M. Sustainable Business Practices in Germany: An Analysis of Current Strategies. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 12, 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, M.; Schmidt, P.; Schulz, A.; Wagner, T. CSR Education and Training in Polish Enterprises: An Empirical Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, B.; Schulz, K.; Becker, L. Webinars and Online Courses as Tools for CSR Education in German Companies. J. Corp. Learn. 2022, 13, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, R. The Role of Managers in Transforming Business Practices for Social and Environmental Benefits: A Comparative Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 171, 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Salim, N.; Rahman, M.N.A.; Wahab, D.A. A systematic literature review of internal capabilities for enhancing eco-innovation performance of manufacturing firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamojski, P.; Wroblewski, L. CSR Impact on Business Practices in Poland: A Managerial Perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M.; Schmidt, L.; Becker, M. The Impact of Management on CSR and Sustainable Business in Germany. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 30, 40–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lončar, D.; Paunković, J.; Jovanović, V.; Krstić, V. Environmental and social responsibility of companies cross EU countries—Panel data analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, U. CSR Strategies and the Role of Managers in Germany: An Analysis of Trends and Perspectives. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 17, 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki, B.; Jankowski, P.; Korzeniowski, G. Building the Culture of the Organization through CSR: A Polish Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 160, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, F.; Wagner, T.; Schmidt, A. Encouraging the Involvement of All Employees in CSR: A German Study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bastas, A.; Liyanage, K. Setting a framework for organisational sustainable development. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 20, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, H.; Becker, T.; Schmidt, L. Balancing Economic Opportunities and Social Responsibility in Germany: A Managerial Perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stawicki, M. The Impact of Management on the Reputation of Socially Responsible Companies: A Study in Poland. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2021, 24, 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, B. Promoting Sustainable Development and Social Inclusion in German Companies: A Managerial Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 40–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cantele, S.; Zardini, A. Is sustainability a competitive advantage for small businesses? An empirical analysis of possible mediators in the sustainability–financial performance relationship. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; Wagner, D.; Schultz, L. Maintaining Social and Ecological Responsibility in Germany: A Managerial Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 170, 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, T.; Zygmunt, A.; Szczepanski, M. CSR in Poland: Balancing New Economic Opportunities and Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, P.; Wagner, L.; Braun, M. Sustainable Development in the German Business Context: A Managerial Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- GOV. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/fundusze-regiony/wspieramy-rozwoj-odpowiedzialnych-polityk-pracowniczych-inauguracja-przewodnika-csr-po-bezpiecznym-i-zrownowazonym-srodowisku-pracy (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Wirth, H.; Schmidt, B.; Becker, M. Balancing Economic Growth and Social Responsibility in Germany: A Study on the Challenges Faced by Managers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wilk, I. Corporate social responsibility and the pro-ecological activity of the enterprise on the market. In Zeszyty Naukowe; No. 662. Economic Problems of Services No. 74; Research of the University of Szczecin: Szczecin, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, S. German Managers and the Challenge of Balancing Economic Growth and Social Responsibility. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2023, 15, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Czarniak, A.; Zaremba, W.; Strzelecki, M. The Future of CSR in Poland: Perspectives and Implications for Managers. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 175, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, L.; Fischer, A.; Beckmann, M. CSR in the Future of Germany: The Role of Managers in Balancing Economic and Social Responsibilities. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 31, 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, L.; Chen, V.Y.-J. Is environmental disclosure an effective strategy on establishment of environmental legitimacy for organization? Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1462–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, F. CSR Practices in Germany: A Future Perspective for Managers. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2023, 16, 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski, K. CSR Guidelines and the Role of Management in Polish Companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 180, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Haseeb, M.; Hussain, H.I.; Kot, S.; Androniceanu, A.; Jermsittiparsert, K. Role of social and technological challenges in achieving a sustainable competitive advantage and sustainable business performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygmunt, A.; Szczepanski, M.; Kowalski, T. Sustainability and Social Inclusion in Polish Companies: The Role of Management. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2023, 20, 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, L.; Wagner, D.; Braun, M. Sustainability and Social Inclusion in German Companies: A Managerial Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 31, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, P.; Piasecki, B.; Korzeniowski, G. Unique Opportunities and Challenges in CSR for Polish Managers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, T.; Schultz, F.; Schmidt, A. Unique Opportunities and Challenges in CSR for German Managers. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 183, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I.; Mućko, P. CSR Reporting Practices of Polish Energy and Mining Companies. Sustainability 2016, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, A. Fostering Sustainability and Reducing CO2 Emissions: Managerial Initiatives in German Companies. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 110, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ozbekler, T.M.; Ozturkoglu, Y. Analysing the importance of sustainability-oriented service quality in competition environment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1504–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orji, I.J. Examining barriers to organizational change for sustainability and drivers of sustainable performance in the metal manufacturing industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soytas, M.A.; Denizel, M.; Usar, D.D. Addressing endogeneity in the causal relationship between sustainability and financial performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 210, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Sağsan, M. Impact of knowledge management practices on green innovation and corporate sustainable development: A structural analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneipp, J.M.; Gomes, C.M.; Bichueti, R.S.; Frizzo, K.; Perlin, A.P. Sustainable innovation practices and their relationship with the performance of industrial companies. Rev. Gestão 2019, 26, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M.; Nasiri, M.; Ukko, J.; Rantala, T. Smart technologies and corporate sustainability: The mediation effect of corporate sustainability strategy. Comput. Ind. 2019, 108, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, H. More Balanced Evaluation Models for CSR: Insights from Germany. Bus. Soc. 2021, 60, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Miciuła, I.; Stępień, P. The Impact of Current EU Climate and Energy Policies on the Economy of Poland. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2019, 28, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukurba, M.; Waszkiewicz, A.E.; Salwin, M.; Kraslawski, A. Co-Created Values in Crowdfunding for Sustainable Development of Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwin, M.; Jacyna-Gołda, I.; Bańka, M.; Varanchuk, D.; Gavina, A. Using Value Stream Mapping to Eliminate Waste: A Case Study of a Steel Pipe Manufacturer. Energies 2021, 14, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T. The Conflict between Short-Term Financial Goals and Long-Term CSR: A Polish Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 170, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, P. Balancing Economic Expectations with CSR Benefits in Poland: A Managerial Challenge. Bus. Soc. 2023, 61, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniec, M.; Zur, A. Business model innovation in corporate entrepreneurship: Exploratory insights from corporate accelerators. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 865–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]