How Can Psychology Contribute to Climate Change Governance? A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aim and Rationale of the Study

- To what extent, under which fields, and how have psychological literature and climate governance issues met?

- How does psychology dialogue with other disciplines on a climate governance terrain?

- Which main psychological concepts, models and theories have been applied in the climate governance field?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Search Strategy

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

- The articles had to investigate climate-related issues, i.e., climate change had to play a clear role in the genesis of the problems under scrutiny;

- The issue had to be addressed within a governance framework, according to the IPCC’s definition of governance (see Section 1);

- Reference to psychological theories, models or factors had to be present.

- Publication exclusion was therefore based on one or more of the following reasons:

- The issues under scrutiny did not originate from climate change;

- There was a lack of a governance framework;

- No psychological perspective or concepts were present, or just an extremely vague and cursor reference to non-specified psychological factors was cited;

- The record was a short and general summary or commentary.

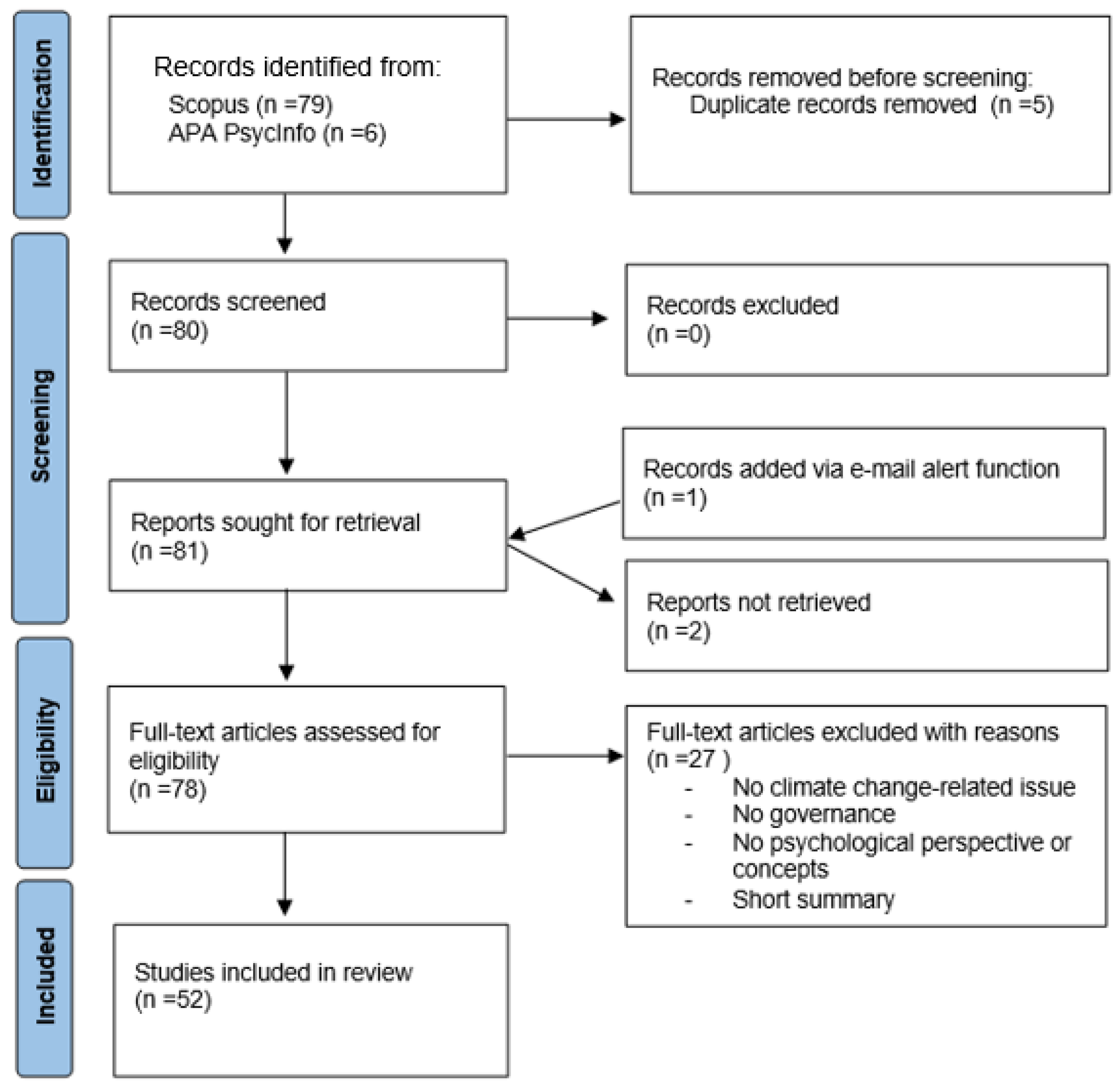

3.3. Process of Research Selection

4. Results

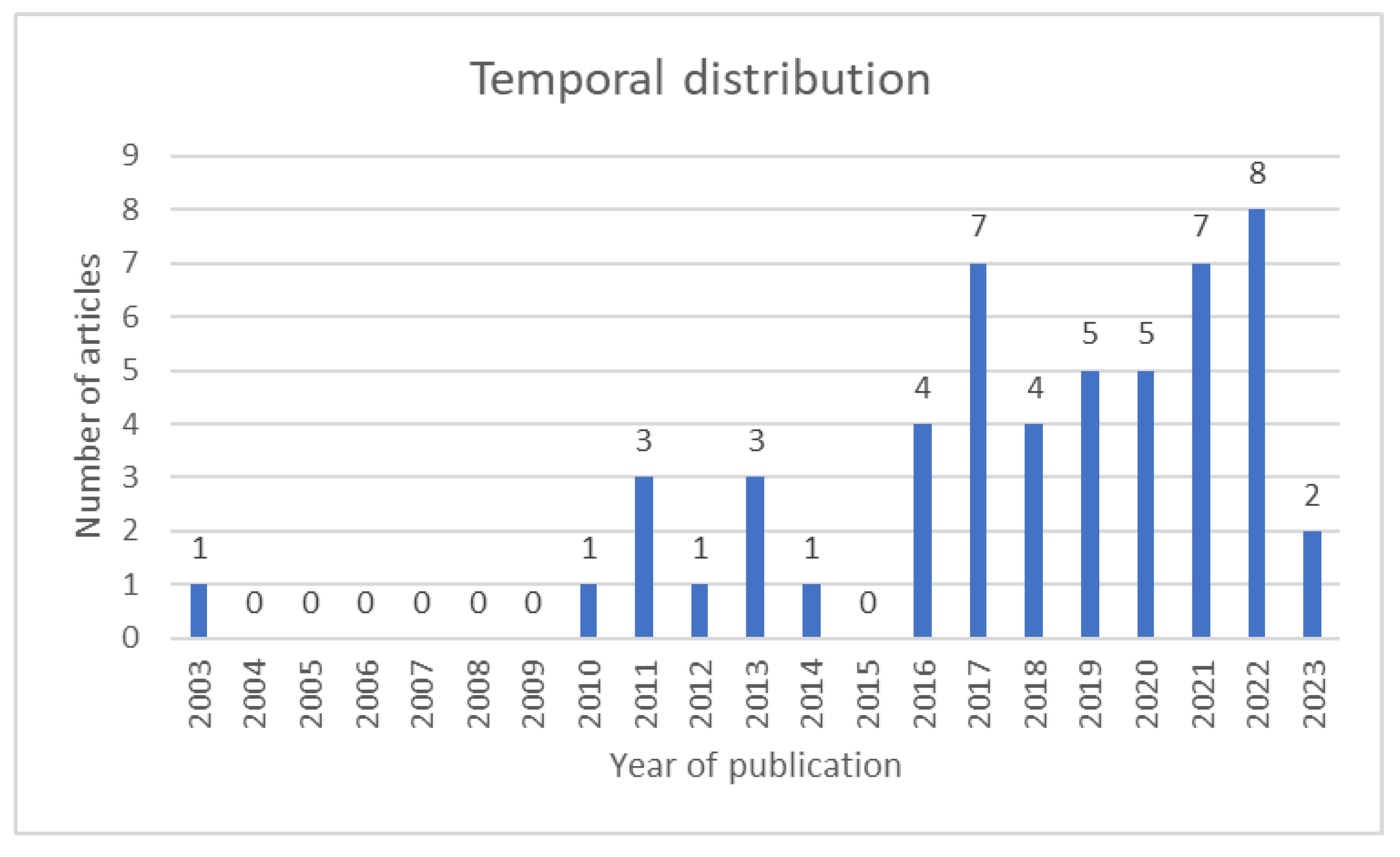

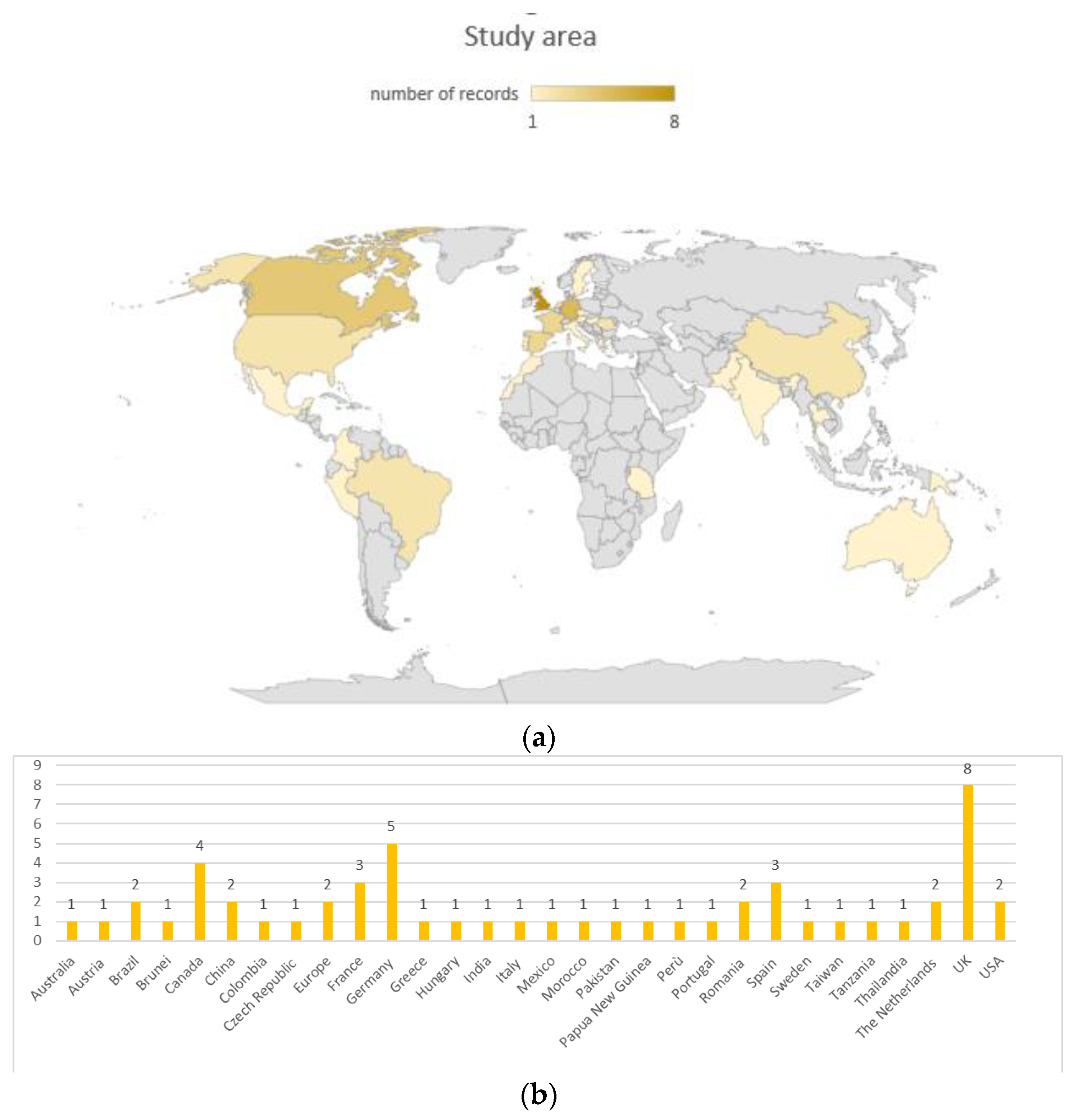

4.1. Timeline and Study Area

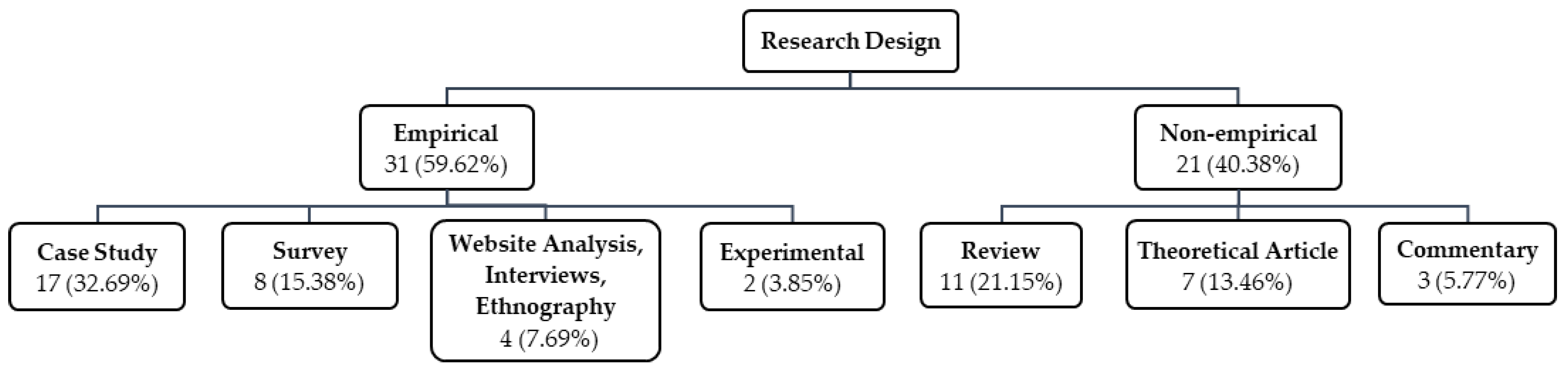

4.2. Research Designs and Methods

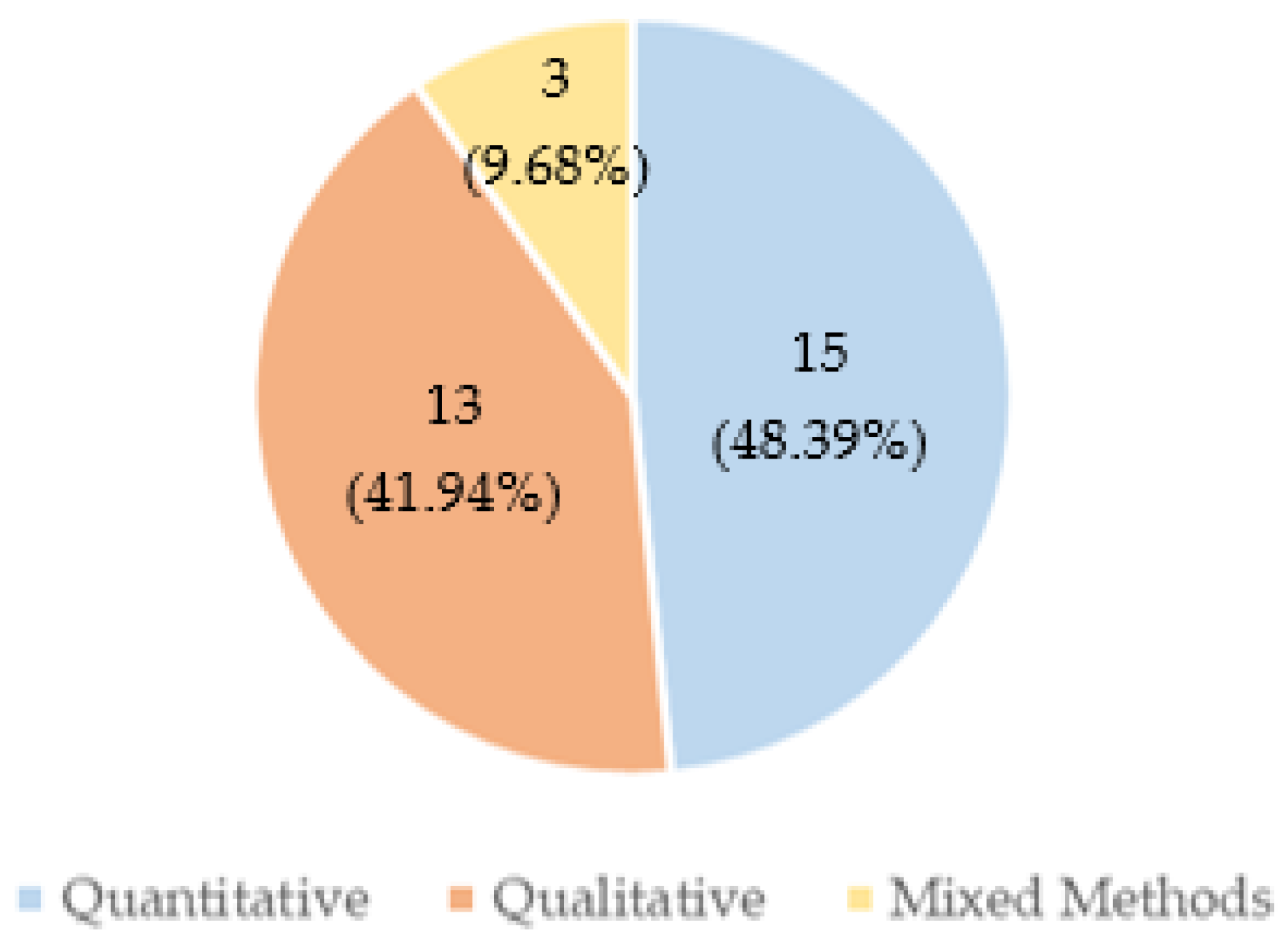

4.3. Disciplinary Fields

4.4. Governance Level and Type

4.5. Psychological Factors, Models and Theories

4.5.1. Cluster 1: Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behaviors

4.5.2. Cluster 2: People’s Perceptions and Views

4.5.3. Cluster 3: Group-Based Processes

5. Discussion

5.1. An Overview of the Study

5.2. Governance between Policy and Politics

5.3. Toward an Ecological Perspective

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

- A relative scarcity of research takes a psychological perspective with respect to the large pool of studies related to the governance of climate change, yet with the few identified studies covering a wide spectrum of climate governance issues spanning different domains and scales.

- A marked interdisciplinary engagement for psychology in the field of climate governance is substantiated by a deep integration with social sciences and environmental sciences’ stances. Similarly, we note a lack of theoretical specificity and depth of the proposed psychological approaches.

- There is a limited portion of research about the processual and relational dimension of governance, and an emphasis on people’s reaction to already established environmental policies, without considering the active engagement of citizenry in the process of policy crafting or in other examples of networked, collaborative forms of governance involving citizens and stakeholders in climate experimentation.

- There is an abundance of studies whose specific psychological contribution consists of investigating the drivers and barriers of different types of pro-environmental behaviours (first cluster), focusing on intra-individual cognitive factors, and a scarcity of context-grounded approaches emphasising the qualifying intergroup, political and social dimension of governance challenges.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Sygna, L. Responding to Climate Change: The Three Spheres of Transformation. Proc. Transform. Chang. Clim. 2013, 16, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Wamsler, C.; Osberg, G. Transformative Climate Policy Mainstreaming—Engaging the Political and the Personal. Global Sustain. 2022, 5, E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F.P. Climate Change: A Wicked Problem: Complexity and Uncertainty at the Intersection of Science, Economics, Politics, and Human Behavior; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, K.; Cashore, B.; Bernstein, S.; Auld, G. Overcoming the tragedy of super wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sci. 2012, 45, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funtowicz, S.O.; Ravetz, J.R. Science for the post-normal age. Futures 1993, 25, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, A.J.; Eriksen, S.; Taylor, M.; Forsyth, T.; Pelling, M.; Newsham, A.; Boyd, E.; Brown, K.; Harvey, B.; Jones, L.; et al. Beyond technical fixes: Climate solutions and the great derangement. Clim. Dev. 2019, 12, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castree, N.; Adams, W.M.; Barry, J.; Brockington, D.; Büscher, B.; Corbera, E.; Demeritt, D.; Duffy, R.; Felt, U.; Neves, K.; et al. Changing the intellectual climate. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, E.L.; Dubash, N.K.; Mulugetta, Y. Climate change research and the search for solutions: Rethinking interdisciplinarity. Clim. Chang. 2021, 168, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA. Addressing the climate crisis: An action plan for psychologists (summary). Am. Psychol. 2022, 77, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S. The psychological impacts of global climate change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C.; Clayton, S. Threats to mental health and wellbeing associated with climate change. In Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses; Clayton, S., Manning, C., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Bagrodia, R.; Pfeffer, C.C.; Meli, L.; Bonanno, G.A. Anxiety and resilience in the face of natural disasters associated with climate change: A review and methodological critique. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 76, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.J. Individual impacts and resilience. In Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses; Clayton, S., Manning, C., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G. Chronic environmental change: Emerging ‘Psychoterratic’ syndromes. In Climate Change and Human Well-being: Global Challenges and Opportunities; Weissbecker, I., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stollberg, J.; Jonas, E. Existential threat as a challenge for individual and collective engagement: Climate change and the motivation to act. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, G. ′Solastalgia′. A new concept in health and identity. PAN Philos. Activism Nat. 2005, 3, 41–55. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.897723015186456 (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Galway, L.P.; Beery, T.; Jones-Casey, K.; Tasala, K. Mapping the Solastalgia literature: A scoping review study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, R.; Randell, A.; Lavoie, S.; Gao, C.X.; Manrique, P.C.; Anderson, R.; McDowell, C.; Zbukvic, I. Empirical evidence for climate concerns, negative emotions and climate-related mental ill-health in young people: A scoping review. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2023, 17, 537–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: Dimensions, determinants and change over time. Global Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, D.; Douglas, K.M. The social consequences of conspiracism: Exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one’s carbon footprint. Br. J. Psychol. 2013, 105, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddlestone, M.; Azevedo, F.; Van der Linden, S. Climate of conspiracy: A meta-analysis of the consequences of belief in conspiracy theories about climate change. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 46, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Capstick, S. Perceptions of climate change. In Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perception, Impacts and Responses; Clayton, S., Manning, C., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 46–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, J.; Dietrich, M.; Jost, J.T. The ideological divide and climate change opinion: “to-down” and “bottom-up” approaches. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N. The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Anal. 2011, 32, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, A.; Dessai, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Morton, T.A.; Pidgeon, N.F. Psychological responses to the proximity of climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, E.; Marsh, J.E.; Richardson, B.; Ball, L.J. A systematic review of the psychological distance of climate change: Towards the development of an evidence-based construct. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiella, R.; La Malva, P.; Marchetti, D.; Pomarico, E.; Di Crosta, A.; Palumbo, R.; Cetara, L.; Di Domenico, A.; Verrocchio, M.C. The psychological distance and climate change: A systematic review on the mitigation and adaptation behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 568899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fielding, K.S.; Hornsey, M.J.; Swim, J.K. Developing a social psychology of climate change. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lange, P.A.; Joireman, J.; Milinski, M. Climate change: What psychology can offer in terms of insights and solutions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 27, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, J. Overcoming the ‘value-action gap’ in environmental policy: Tensions between national policy and local experience. Local Environ. 1999, 4, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolske, K.S.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Explaining interest in adopting residential solar photovoltaic systems in the United States: Toward an integration of behavioral theories. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 25, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. Extending the theory of planned behavior model to explain people’s energy savings and carbon reduction behavioral intentions to mitigate climate change in Taiwan–moral obligation matters. J. Cleaner Prod. 2016, 112, 1746–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canova, L.; Manganelli, A.M. Energy-saving behaviours in workplaces: Application of an extended model of the theory of planned behaviour. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolske, K.S.; Stern, P. Contributions of psychology to limiting climate change Opportunities through consumer behavior. In Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses; Clayton, S., Manning, C., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 232–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcicky, P.; Seebauer, S. Unpacking protection motivation theory: Evidence for a separate protective and non-protective route in private flood mitigation behavior. J. Risk Res. 2019, 22, 1503–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grothmann, T.; Patt, A. Adaptive capacity and human cognition: The process of individual adaptation to climate change. Global Environ. Chang. 2005, 15, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Valkengoed, A.M.; Steg, L. The Psychology of Climate Change Adaptation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van Valkengoed, A.M.; Steg, L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Poortinga, W.; Capstick, S. Behaviour change to address climate change. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzell, D.; Räthzel, N. Transforming environmental psychology. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.S.; Clayton, S.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Capstick, S.; Whitmarsh, L. How psychology can help limit climate change. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batel, S.; Castro, P.; Devine-Wright, P.; Howarth, C. Developing a critical agenda to understand pro-environmental actions: Contributions from social representations and social practices theories. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2016, 7, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A.E. Psychological science’s contributions to a sustainable environment: Extending our reach to a grand challenge of society. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inauen, J.; Contzen, N.; Frick, V.; Kadel, P.; Keller, J.; Kollmann, J.; Mata, J.; Van Valkengoed, A.M. Environmental issues are health issues. Eur. Psychol. 2021, 26, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.T.; Neufeld, S.D.; Mackay, C.M.; Dys-Steenbergen, O. The perils of explaining climate inaction in terms of psychological barriers. J. Soc. Issues 2020, 76, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.; Leung, A.K.; Clayton, S. Research on climate change in social psychology publications: A systematic review. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 24, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.A.; Trott, C.D.; Silka, L.; Lickel, B.; Clayton, S. Psychological perspectives on community resilience and climate change. In Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses; Clayton, S., Manning, C., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.L.; Waite, T.D.; Dear, K.B.; Capon, A.G.; Murray, V. The case for systems thinking about climate change and mental health. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Social issues and personal life: Considering the environment. J. Soc. Issues 2017, 73, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Huitema, D.; Van Asselt, H.; Foster, J. Governing Climate Change: Polycentricity in Action? Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, P.; Driessen, P.P.; Sauer, A.; Bornemann, B.; Burger, P. Governing towards sustainability—Conceptualizing modes of governance. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2013, 15, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A polycentric approach for coping with climate change. Ann. Econ. Financ. 2014, 15, 71–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, S.; Meisch, S. Co-production in Climate Change Research: Reviewing Different Perspectives. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasanoff, S. States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Norström, A.V.; Cvitanovic, C.; Löf, M.F.; West, S.; Wyborn, C.; Balvanera, P.; Bednarek, A.T.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; de Bremond, A.; et al. Principles for Knowledge Co-Production in Sustainability Research. Nat. Sust. 2020, 3, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasanoff, S. Technologies of Humility: Citizen Participation in Governing Science. Minerva 2003, 41, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); UN: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Available online: https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- United Nations (UN). Paris Agreement; UN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Hölscher, K.; Frantzeskaki, N. A transformative perspective on climate change and climate governance. In Transformative Climate Governance A Capacities Perspective to Systematise, Evaluate and Guide Climate Action; Hölscher, K., Frantzeskaki, N., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020; pp. 3–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Moser, S.C. Responding to climate change: Governance and social action beyond Kyoto. Global Environ. Politics 2007, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Castán Broto, V. Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2012, 38, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castán Broto, V.; Bulkeley, H. A survey of urban climate change experiments in 100 cities. Global Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castán Broto, V. Urban governance and the politics of climate change. World Dev. 2017, 93, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Árvai, J.; Gregory, R. Beyond choice architecture: A building code for structuring climate risk management decisions. Behav. Public Policy 2020, 5, 556–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versey, H.S. Missing pieces in the discussion on climate change and risk: Intersectionality and compounded vulnerability. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2021, 8, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaei Chadegani, A.; Salehi, H.; Yunus, M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Ale Ebrahim, N. A Comparison between Two Main Academic Literature Collections: Web of Science and Scopus Databases. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckute, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, J.; Turnbull-Dugarte, S.J. Populist attitudes and threat perceptions of global transformations and governance: Experimental evidence from India and the United Kingdom. Political Psychol. 2022, 43, 873–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Spekkink, W.; Polzin, C.; Díaz-Ayude, A.; Brizi, A.; Macsinga, I. Social representations of governance for change towards sustainability: Perspectives of sustainability advocates. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galafassi, D.; Tàbara, J.D.; Heras, M. Restoring our senses, restoring the earth. Fostering imaginative capacities through the arts for envisioning climate transformations. Elementa Sci. Anthr. 2018, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldívar-Lucio, R.; Trasviña-Castro, A.; Jiddawi, N.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Lindström, L.; Jentoft, S.; Fraga, J.; De la Torre-Castro, M. Fine-tuning climate resilience in marine socio-ecological systems: The need for accurate space-time representativeness to identify relevant consequences and responses. Front. Marine Sci. 2021, 7, 600403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thew, H.; Middlemiss, L.; Paavola, J. “You need a month’s holiday just to get over it!” exploring young people’s lived experiences of the UN climate change negotiations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Peters, V.; Vávra, J.; Neebe, M.; Megyesi, B. Energy use, climate change and folk psychology: Does sustainability have a chance? Results from a qualitative study in five European countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, P.; Mouro, C. Psycho-social processes in dealing with legal innovation in the community: Insights from biodiversity conservation. Am. J. Comm. Psychol. 2011, 47, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Cohen, S. Why sustainable transport policies will fail: EU climate policy in the light of transport taboos. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 39, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idier, D.; Castelle, B.; Poumadère, M.; Balouin, Y.; Bertoldo, R.; Bouchette, F.; Boulahya, F.; Brivois, O.; Calvete, D.; Capo, S.; et al. Vulnerability of sandy coasts to climate variability. Clim. Res. 2013, 57, 19–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.; McNamara, K.E.; Witt, B. “System of hunger”: Understanding causal disaster vulnerability of Indigenous food systems. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 73, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J.D.; Becken, S.; Curnock, M. Gaining public engagement to restore coral reef ecosystems in the face of acute crisis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2022, 74, 102513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batel, S.; Devine-Wright, P. Energy colonialism and the role of the global in local responses to new energy infrastructures in the UK: A critical and exploratory empirical analysis. Antipode 2017, 49, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatti, M.; Sieber, S.; Schlindwein, S.L.; Lana, M.A.; De Vasconcelos, A.C.; Gentile, E.; Boulanger, J.; Plencovich, M.C.; Malheiros, T.F. Climate vulnerability and contrasting climate perceptions as an element for the development of community adaptation strategies: Case studies in southern Brazil. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez Bossio, C.; Labbé, D.; Ford, J. Urban dwellers’ adaptive capacity as a socio-psychological process: Insights from Lima, Peru. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 34, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecksch, K. Adaptive capacity and regional water governance in north-western Germany. Water Policy 2013, 15, 794–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothmann, T.; Grecksch, K.; Winges, M.; Siebenhüner, B. Assessing institutional capacities to adapt to climate change: Integrating psychological dimensions in the adaptive capacity wheel. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 3369–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, I.A.; Lodhi, R.H.; Zia, A.; Jamshed, A.; Nawaz, A. Three-step neural network approach for predicting monsoon flood preparedness and adaptation: Application in urban communities of Lahore, Pakistan. Urban Clim. 2022, 45, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touza, J.; Lacambra, C.; Kiss, A.; Amboage, R.M.; Sierra, P.; Solan, M.; Godbold, J.A.; Spencer, T.; White, P.C. Coping and adaptation in response to environmental and climatic stressors in Caribbean coastal communities. Environ. Manag. 2021, 68, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foguesatto, C.R.; Machado, J.A. What shapes farmers’ perception of climate change? A case study of southern Brazil. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottwald, S.; Stedman, R.C. Preserving ones meaningful place or not? Understanding environmental stewardship behaviour in river landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 198, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Tung, C.; Lin, S. Attitudes to climate change, perceptions of disaster risk, and mitigation and adaptation behavior in Yunlin County, Taiwan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 26, 30603–30613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muenratch, P.; Nguyen, T.P. Determinants of water use saving behaviour toward sustainable groundwater management. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 20, 100898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazart, C.; Trouillet, R.; Rey-Valette, H.; Lautrédou-Audouy, N. Correction to: Improving relocation acceptability by improving information and governance quality: Results from a survey conducted in France. Clim. Chang. 2020, 160, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheval, S.; Bulai, A.; Croitoru, A.; Dorondel, Ș.; Micu, D.; Mihăilă, D.; Sfîcă, L.; Tișcovschi, A. Climate change perception in Romania. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 149, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, L. Explaining gender differences in private forest risk management. Scand. J. Forest Res. 2018, 33, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Glenk, K. One model fits all?—On the moderating role of emotional engagement and confusion in the elicitation of preferences for climate change adaptation policies. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Xing, X. The antecedent and performance of environmental managers’ proactive pollution reduction behavior in Chinese manufacturing firms: Insight from the proactive behavior theory. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 242, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xing, X.; Song, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Green organizational identity and sustainable innovation in the relationship between environmental regulation and business sustainability: Evidence from China’s manufacturers. J. Gen. Manag. 2022, 47, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, H.W.; Williamson, T.B.; Macaulay, C.; Mahony, C. Assessing the potential for forest management practitioner participation in climate change adaptation. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2016, 360, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S.; Leverkus, A.B.; Thorn, C.J.; Beudert, B. Education and knowledge determine preference for bark beetle control measures in El Salvador. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 232, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, R. Climates of suspicion: ‘chemtrail’ conspiracy narratives and the international politics of geoengineering. Geogr. J. 2014, 182, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R.; Nachmany, M. ‘A very human business’—Transnational networking initiatives and domestic climate action. Global Environ. Chang. 2019, 54, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorman, D.; Whitmarsh, L.; Demski, C. Policy acceptance of low-consumption governance approaches: The effect of social norms and hypocrisy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Shelley, A.; Van Zeijl-Rozema, A.; Martens, P. A conceptual synthesis of organisational transformation: How to diagnose, and navigate, pathways for sustainability at universities? J. Cleaner Prod. 2017, 145, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, S.M.; Weber, E.U. Decision-making under the deep uncertainty of climate change: The psychological and political agency of narratives. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 42, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R.K.; Garmestani, A.S.; Allen, C.R.; Arnold, C.A.; Birgé, H.; DeCaro, D.A.; Fremier, A.K.; Gosnell, H.; Schlager, E. Balancing stability and flexibility in adaptive governance: An analysis of tools available in U.S. environmental law. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.; Fischer, A.P.; Guikema, S.D.; Keppel-Aleks, G. Behavioral adaptation to climate change in wildfire-prone forests. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2018, 9, e553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishant, R.; Kennedy, M.; Corbett, J. Artificial intelligence for sustainability: Challenges, opportunities, and a research agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidgeon, N. Public understanding of, and attitudes to, climate change: UK and international perspectives and policy. Clim. Policy 2012, 12, S85–S106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, L.; Kelly, D.; Hennes, E.P. Norm-based governance for severe collective action problems: Lessons from climate change and COVID-19. Perspect. Politics 2021, 21, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shwom, R.; Kopp, R.E. Long term risk governance: When do societies act before crisis? J. Risk Res. 2018, 22, 1374–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Schoenefeld, J.J. Collective climate action and networked climate governance. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2017, 8, e440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, T.B.; Nelson, H.W. Barriers to enhanced and integrated climate change adaptation and mitigation in Canadian forest management. Can. J. Forest Res. 2017, 47, 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral, L.; Van der Werff, P.; Bakker, K.; Handmer, J. Global trends and water policy in Spain. Water Int. 2003, 28, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gicquello, M. The failures of COP26: Using group psychology and dynamics to scale up the adoption of climate mitigation and adaptation measures. Transnatl. Leg. Theory 2022, 13, 366–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gousse-Lessard, A.; Gachon, P.; Lessard, L.; Vermeulen, V.; Boivin, M.; Maltais, D.; Landaverde, E.; Généreux, M.; Motulsky, B.; Le Beller, J. Intersectoral approaches: The key to mitigating psychosocial and health consequences of disasters and systemic risks. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 32, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, R.; Weber, E.U. Multilevel intergroup conflict at the core of climate (in)justice: Psychological challenges and ways forward. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2023, 14, e836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndah, A.B.; Odihi, J.O. A systematic study of disaster risk in Brunei Darussalam and options for vulnerability-based disaster risk reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2017, 8, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Okereke, C. A six-component model for assessing procedural fairness in the intergovernmental panel on climate change (IPCC). Clim. Chang. 2017, 145, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykoff, M. Consensus and contrarianism on climate change: How the USA case informs dynamics elsewhere. Mètode Sci. Stud. J. 2016, 6, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spash, C.L. The Brave new world of carbon trading. New Political Econ. 2010, 15, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whomsley, S.R. Five roles for psychologists in addressing climate change, and how they are informed by responses to the COVID-19 outbreak. Eur. Psychol. 2021, 26, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reser, J.P.; Swim, J.K. Adapting to and coping with the threat and impacts of climate change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, S. Notes towards a description of social representations. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 18, 211–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovici, S. Social Representations: Essays in Social Psychology; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, J.; Termeer, C.; Klostermann, J.; Meijerink, S.; Van den Brink, M.; Jong, P.; Noteboom, S.; Bergsma, E. The adaptive capacity wheel: A method to assess the inherent characteristics of institutions to enable the adaptive capacity of society. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Crant, J.M. Proactive behavior in organizations. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.K.; Hogg, T.L.; Leviston, Z.; Walker, I. From anger to action: Differential impacts of eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-anger on climate action and wellbeing. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Stern, P.C.; Whitmarsh, L.; Carrico, A.; Steg, L.; Swim, J.; Bonnes, M. Psychological research and global climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyster, H.N.; Satterfield, T.; Chan, K.M. Why people do what they do: An interdisciplinary synthesis of human action theories. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2023, 47, 725–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Osberg, G.; Osika, W.; Herndersson, H.; Mundaca, L. Linking internal and external transformation for sustainability and climate action: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Global Environ. Chang. 2021, 71, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E. Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heft, H. Foundations of an ecological approach to psychology. In The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology; Clayton, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Q.D.; Jacquet, J. Challenging the idea that humans are not designed to solve climate change. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Step | Second Step | |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | Search query: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“climate change” AND governance) | Search query: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“climate change” AND “governance” AND “psycholog*”) |

| Identified records: 8002 (journal articles in English) | Identified records: 79 (journal articles in English) | |

| PsycInfo | Search query: AB “climate change” AND AB governance | Search query: AB “climate change” AND AB governance AND AB psycholog* |

| Identified records: 69 (journal articles in English) | Identified records: 6 (journal articles in English) |

| Governance Level | n (%) | References | Subtotal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-level Perspective | Local National Organizational International | 14 (26.92%) 3 (5.77%) 3 (5.77%) 4 (7.69%) | [80,81,82,87,88,91,92,95,96,97,98,99,100,115] [102,108,118] [105,106,112] [79,83,109,116] | 24 (46.15%) |

| Two-level Perspective | Local/National National/International | 13 (25%) 4 (7.69%) | [84,89,93,94,101,104,107,111,114,119,121,126] [86,110,123,128] | 17 (32.69%) |

| Multilevel Perspective | 11 (21.15%) | [85,90,113,116,117,120,122,124,127,129,130] | 11 (21.15%) | |

| Total | 52 (100%) | |||

| Governance Scope | n (%) | References | Main Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptation | 29 (55.78%) | [81,82,87,88,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,99,101,102,103,104,107,113,114,115,116,117,119,121,122,123,124,126,130] | Disaster preparedness Risk governance Local vulnerability Adaptation policies and planning Development of adaptive capacities Knowledge co-production about risks and viable solutions |

| New Governance Structures, Processes and Tools | 18 (34.61%) | [79,83,85,106,110,112,113,114,116,117,118,120,123,125,127,128,129,130] | New climate governance strategies and solutions Decision-making and relational dynamics in climate negotiations Organizational transformations toward sustainability Responses to legal innovation |

| Mitigation | 17 (32.69%) | [80,84,86,90,99,102,105,107,109,111,113,116,117,120,123,129,130] | Mitigation and energy policies Sustainable production and consumption Mitigation-related collective action |

| Natural Resources and Ecosystems Conservation | 12 (23.08%) | [85,89,98,100,103,107,108,113,116,121,122,130] | Ecosystem restoration Forest governance Water management Environmental stewardship |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Freschi, G.; Menegatto, M.; Zamperini, A. How Can Psychology Contribute to Climate Change Governance? A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914273

Freschi G, Menegatto M, Zamperini A. How Can Psychology Contribute to Climate Change Governance? A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914273

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreschi, Gloria, Marialuisa Menegatto, and Adriano Zamperini. 2023. "How Can Psychology Contribute to Climate Change Governance? A Systematic Review" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914273

APA StyleFreschi, G., Menegatto, M., & Zamperini, A. (2023). How Can Psychology Contribute to Climate Change Governance? A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 15(19), 14273. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914273