Institutional Pressures on Sustainability and Green Performance: The Mediating Role of Digital Business Model Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Frameworks

2.1. Institutional Pressures on Sustainability

2.2. Digital Business Model Innovation

2.3. Green Performance

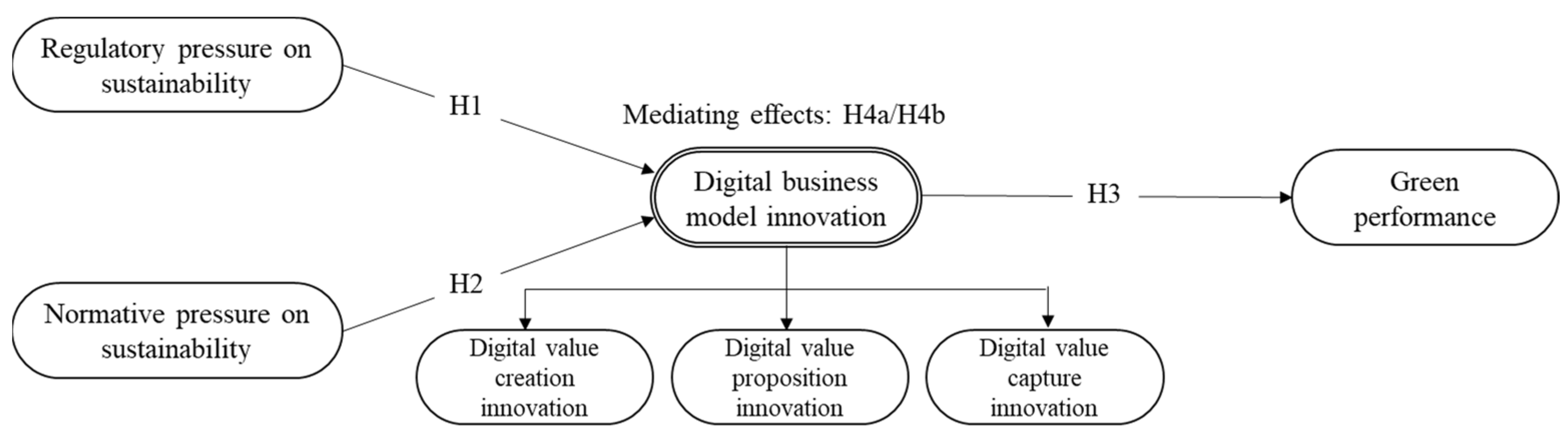

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Institutional Pressures on Sustainability and Digital Business Model Innovation

3.2. Digital Business Model Innovation and Green Performance

3.3. Digital Business Model Innovation and Its Mediating Effect

4. Research Methods and Results

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

4.2. Variables and Measurement

4.3. Bias Tests

4.4. Reliability and Validity of the Model

4.5. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gunarathne, A.N.; Lee, K.H.; Hitigala Kaluarachchilage, P.K. Institutional pressures, environmental management strategy, and organizational performance: The role of environmental management accounting. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Vladimirova, D.; Holgado, M.; Van Fossen, K.; Yang, M.; Silva, E.A.; Barlow, C.Y. Business model innovation for sustainability: Towards a unified perspective for creation of sustainable business models. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, A.; Yasir, M.; Yasir, M.; Javed, A. Nexus of institutional pressures, environmentally friendly business strategies, and environmental performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Yimamu, N.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.; Irfan, M.; Hao, Y. Digitalization and sustainable development: How could digital economy development improve green innovation in China? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1847–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluza, K.; Ziolo, M.; Spoz, A. Innovation and environmental, social, and governance factors influencing sustainable business models-Meta-analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 127015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Rong, Z.; Ji, Q. Green innovation and firm performance: Evidence from listed companies in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 144, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H. How organizational green culture influences green performance and competitive advantage: The mediating role of green innovation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkdahl, J. Strategies for digitalization in manufacturing firms. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2020, 62, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, B.; Lam, E.; Girard, K.; Irvin, V. Digital transformation is not about technology. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabpour, V.; Oghazi, P.; Toorajipour, R.; Nazarpour, A. Export sales forecasting using artificial intelligence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Burström, T.; Visnjic, I.; Wincent, J. Orchestrating industrial ecosystem in circular economy: A two-stage transformation model for large manufacturing companies. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Briel, F. The future of omnichannel retail: A four-stage Delphi study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 132, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, J.; Liu, J. Factors influencing consumers’ purchase decision-making in O2O business model: Evidence from consumers’ overall evaluation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Seuring, S.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Jugend, D.; Fiorini, P.D.C.; Latan, H.; Izeppi, W.C. Stakeholders, innovative business models for the circular economy and sustainable performance of firms in an emerging economy facing institutional voids. J. Envrion. Manag. 2020, 264, 110416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, S.K.; Mangla, S.K.; Luthra, S.; Kusi-Sarpong, S. When stakeholder pressure drives the circular economy: Measuring the mediating role of innovation capabilities. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 904–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, J.; Wu, T. China’s entry to WTO: Global marketing issues, impact, and implications for China. Int. Mark. Rev. 2004, 21, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Xu, D. Relationship between energy consumption, economic growth and environmental pollution in China. Environ. Res. 2021, 194, 110718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.-L.; Kong, D.; Tan, W.; Wang, W. Being good when being international in an emerging economy: The case of China. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lo, C.W.H.; Li, P.H.Y. Organizational visibility, stakeholder environmental pressure and corporate environmental responsiveness in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.K.; Lai, K.-h.; Cheng, T. A multi-research-method approach to studying environmental sustainability in retail operations. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Ribiere, V. Developing a unified definition of digital transformation. Technovation 2021, 102, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunnermeier, S.B.; Cohen, M.A. Determinants of environmental innovation in US manufacturing industries. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2003, 45, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalabik, B.; Fairchild, R.J. Customer, regulatory, and competitive pressure as drivers of environmental innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiadat, Y.; Kelly, A.; Roche, F.; Eyadat, H. Green and competitive? An empirical test of the mediating role of environmental innovation strategy. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frondel, M.; Horbach, J.; Rennings, K. What triggers environmental management and innovation? Empirical evidence for Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 66, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehfeld, K.-M.; Rennings, K.; Ziegler, A. Integrated product policy and environmental product innovations: An empirical analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Lim, W.M. Digital transformation and business model innovation: Advances, challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Qual. Innov. 2022, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rachinger, M.; Rauter, R.; Müller, C.; Vorraber, W.; Schirgi, E. Digitalization and its influence on business model innovation. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2018, 30, 1143–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregori, P.; Holzmann, P. Digital sustainable entrepreneurship: A business model perspective on embedding digital technologies for social and environmental value creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Röndell, J.; Kowalkowski, C.; Raggio, R.D.; Thompson, S.M. Emergent market innovation: A longitudinal study of technology-driven capability development and institutional work. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckert, J. Institutional isomorphism revisited: Convergence and divergence in institutional change. Sociol. Theory 2010, 28, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Ramanathan, R. An empirical examination of stakeholder pressures, green operations practices and environmental performance. Int. J. Product. Res. 2015, 53, 6390–6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poisson-de Haro, S.; Bitektine, A. Global sustainability pressures and strategic choice: The role of firms’ structures and non-market capabilities in selection and implementation of sustainability initiatives. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Chen, C.T. Exploring institutional pressures, firm green slack, green product innovation and green new product success: Evidence from Taiwan’s high-tech industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Yang, J.; Cui, Y. Institutional pressure and open innovation: The moderating effect of digital knowledge and experience-based knowledge. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 26, 2499–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable competitive advantage: Combining institutional and resource-based views. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, H.-H.; Wei, K.K.; Benbasat, I. Predicting intention to adopt interorganizational linkages: An institutional perspective. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 19–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, S.R.; Joshi, A.W. Corporate ecological responsiveness: Antecedent effects of institutional pressure and top management commitment and their impact on organizational performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Institutional pressures and environmental management practices: The moderating effects of environmental commitment and resource availability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-X.; Hu, Z.-P.; Liu, C.-S.; Yu, D.-J.; Yu, L.-F. The relationships between regulatory and customer pressure, green organizational responses, and green innovation performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3423–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldner, F.; Poetz, M.K.; Grimpe, C.; Eurich, M. Antecedents and consequences of business model innovation: The role of industry structure. In Business Models and Modelling; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2015; Volume 33, pp. 347–386. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M.; Delport, M.; Blignaut, J.N.; Hichert, T.; Van der Burgh, G. Combining theory and wisdom in pragmatic, scenario-based decision support for sustainable development. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 692–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Ricart, J.E. From strategy to business models and onto tactics. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieth, P.; Schneckenberg, D.; Ricart, J.E. Business model innovation–state of the art and future challenges for the field. RD Manag. 2014, 44, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Business Model Innovation Strategy: Transformational Concepts and Tools for Entrepreneurial Leaders; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss, T. Measuring business model innovation: Conceptualization, scale development, and proof of performance. RD Manag. 2017, 47, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşek, T.; Öner, M.A.; Kunday, Ö.; Olcay, G.A. A journey towards a digital platform business model: A case study in a global tech-company. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 175, 121372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go? J. Manag. 2017, 43, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, I.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Panniello, U. Innovating agri-food business models after the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of digital technologies on the value creation and value capture mechanisms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 190, 122404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ippolito, B.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A.; Panniello, U. Archetypes of incumbents’ strategic responses to digital innovation. J. Intellect. Cap. 2019, 20, 662–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, I.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Panniello, U. Digital business model innovation in metaverse: How to approach virtual economy opportunities. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Sjödin, D.; Reim, W. Reviewing literature on digitalization, business model innovation, and sustainable industry: Past achievements and future promises. Sustainability 2019, 11, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaska, S.; Massaro, M.; Bagarotto, E.M.; Dal Mas, F. The digital transformation of business model innovation: A structured literature review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 539363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klos, C.; Spieth, P.; Clauss, T.; Klusmann, C. Digital transformation of incumbent firms: A business model innovation perspective. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 70, 2017–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, M.A.; Gawer, A.; Yoffie, D.B. The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 320. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ngniatedema, T.; Chen, F. Understanding the impact of green initiatives and green performance on financial performance in the US. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the mother of ‘green’inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemans, I.; Porter, A.J.; Diriker, D. Harnessing digitalization for sustainable development: Understanding how interactions on sustainability-oriented digital platforms manage tensions and paradoxes. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordella, A.; Tempini, N. E-government and organizational change: Reappraising the role of ICT and bureaucracy in public service delivery. Gov. Inf. Q. 2015, 32, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMassah, S.; Mohieldin, M. Digital transformation and localizing the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J. Institutional evolution and change: Environmentalism and the US chemical industry. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krell, K.; Matook, S.; Rohde, F. The impact of legitimacy-based motives on IS adoption success: An institutional theory perspective. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. Institutional pressures and support from industrial zones for motivating sustainable production among Chinese manufacturers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 181, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Lee, M.J.; Jung, J.S. Dynamic capabilities and an ESG strategy for sustainable management performance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 887776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-M.; Chen, T.-L.; Yang, C.-S. The effects of institutional pressures on shipping digital transformation in Taiwan. Marit. Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.; Whiteman, G.; van den Ende, J. Radical innovation for sustainability: The power of strategy and open innovation. Long Range Plan. 2017, 50, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J. Impact of total quality management on corporate green performance through the mediating role of corporate social responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, J. Digital transformation, environmental disclosure, and environmental performance: An examination based on listed companies in heavy-pollution industries in China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 87, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pick, J.B.; Nishida, T. Digital divides in the world and its regions: A spatial and multivariate analysis of technological utilization. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 91, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, H.; Yang, M.; Chan, K.C. Does digital transformation enhance a firm’s performance? Evidence from China. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Joshi, S.; Upadhyay, A. The impact of environmental dynamism on low-carbon practices and digital supply chain networks to enhance sustainable performance: An empirical analysis. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1776–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Creating value through business model innovation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. Invited editorial: A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, A.X.; Zhou, K.Z.; Jiang, W. Environmental strategy, institutional force, and innovation capability: A managerial cognition perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Jiang, W. State ownership and green innovation in China: The contingent roles of environmental and organizational factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lei, X.; Wu, W. Can digital investment improve corporate environmental performance?—Empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, Z. Institutional pressures, sustainable supply chain management, and circular economy capability: Empirical evidence from Chinese eco-industrial park firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z. Institutional pressure, knowledge acquisition and a firm’s environmental innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Latan, H.; Sohal, A.S. Stakeholder pressure, green innovation, and performance in small and medium-sized enterprises: The role of green dynamic capabilities. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Roh, T. Unpacking the sustainable performance in the business ecosystem: Coopetition strategy, open innovation, and digitalization capability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. Common method bias in marketing: Causes, mechanisms, and procedural remedies. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.R.D.; Ferreira, F.A.; Teixeira, F.J.; Zopounidis, C. Artificial intelligence, digital transformation and cybersecurity in the banking sector: A multi-stakeholder cognition-driven framework. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022, 60, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Nie, L.; Sun, H.; Sun, W.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. Digital finance, green technological innovation and energy-environmental performance: Evidence from China’s regional economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 327, 129458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dai, J.; Cui, L. The impact of digital technologies on economic and environmental performance in the context of industry 4.0: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 229, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soluk, J.; Miroshnychenko, I.; Kammerlander, N.; De Massis, A. Family influence and digital business model innovation: The enabling role of dynamic capabilities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 45, 867–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, X.; Pang, J.; Xing, H.; Wang, J. The impact of digital transformation of manufacturing on corporate performance—The mediating effect of business model innovation and the moderating effect of innovation capability. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2023, 64, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Koo, J.-M.; Lee, M.-J. How Firms Can Improve Sustainable Performance on Belt and Road Initiative. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Walters, P.G.; Luk, S.T. Chinese puzzles and paradoxes: Conducting business research in China. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | RP | NP | DBMI | GP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory pressure | 0.957 | |||

| Normative pressure | 0.882 | 0.931 | ||

| DBMI * | 0.844 | 0.873 | 0.917 | |

| Green performance | 0.850 | 0.893 | 0.924 | 0.916 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.954 | 0.923 | 0.962 | 0.961 |

| Composite reliability | 0.970 | 0.951 | 0.969 | 0.972 |

| rho_A | 0.955 | 0.924 | 0.963 | 0.964 |

| AVE | 0.915 | 0.867 | 0.840 | 0.896 |

| Path | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval (Lower Bound, Upper Bound) | Hypothesis Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. RP → DBMI | 0.331 | 0.047 | 7.012 | 0.000 | (0.236, 0.423) | Supported |

| H2. NP → DBMI | 0.582 | 0.046 | 12.582 | 0.000 | (0.492, 0.673) | Supported |

| H3. DBMI → GP | 0.923 | 0.008 | 120.228 | 0.000 | (0.907, 0.937) | Supported |

| H4a. RP → DBMI → GP | 0.305 | 0.044 | 6.985 | 0.000 | (0.218, 0.390) | Supported |

| H4b. RP → DBMI → GP | 0.537 | 0.043 | 12.405 | 0.000 | (0.452, 0.623) | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Lee, M.-J. Institutional Pressures on Sustainability and Green Performance: The Mediating Role of Digital Business Model Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914258

Liang Y, Zhao C, Lee M-J. Institutional Pressures on Sustainability and Green Performance: The Mediating Role of Digital Business Model Innovation. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914258

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Yi, Chenyu Zhao, and Min-Jae Lee. 2023. "Institutional Pressures on Sustainability and Green Performance: The Mediating Role of Digital Business Model Innovation" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914258

APA StyleLiang, Y., Zhao, C., & Lee, M.-J. (2023). Institutional Pressures on Sustainability and Green Performance: The Mediating Role of Digital Business Model Innovation. Sustainability, 15(19), 14258. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914258