Novelty and Sustainability: The Generation Process of Original Business Model Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Definition

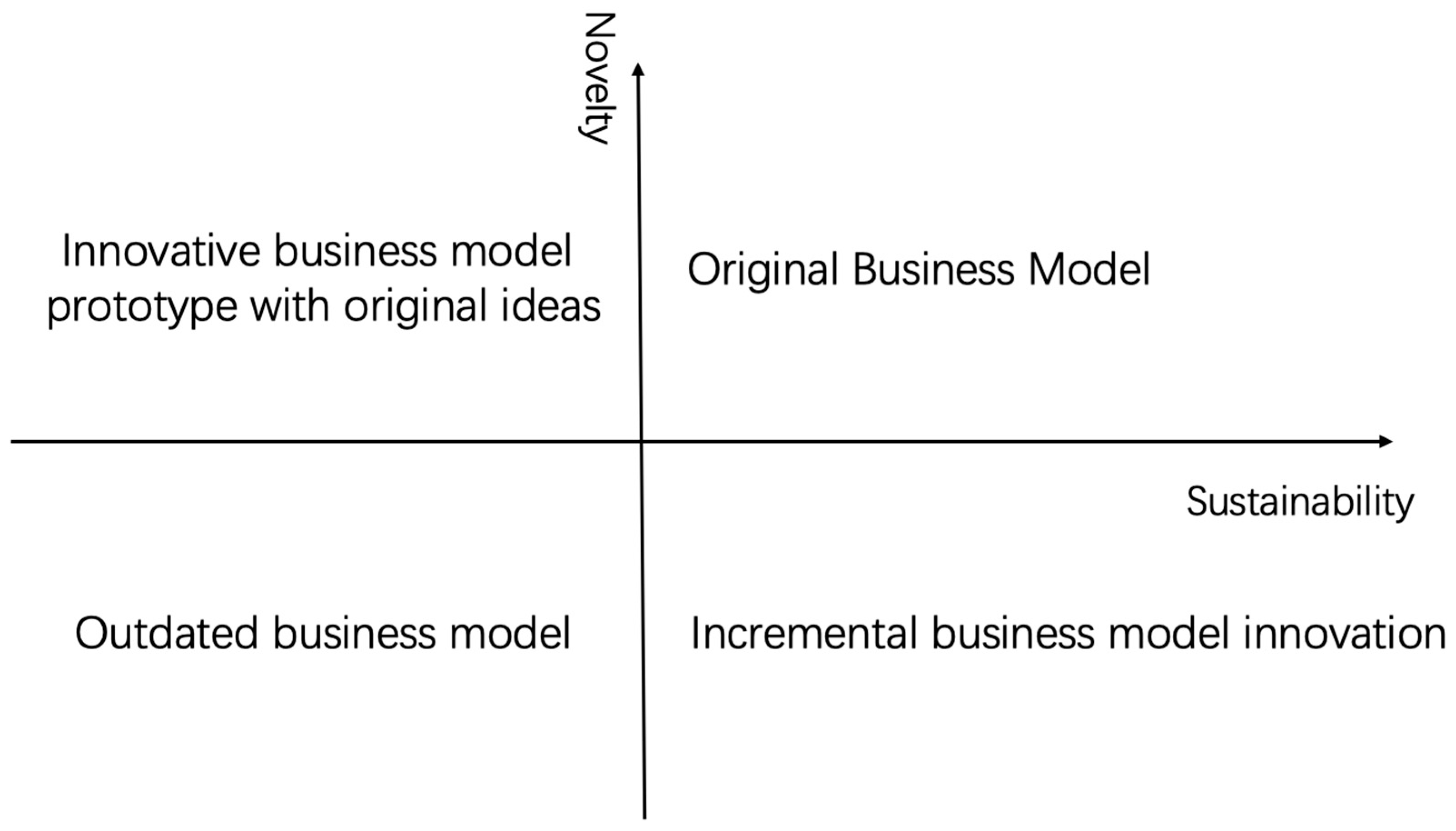

2.1. Original Business Model Innovation

2.2. The Process of Business Model Innovation

3. Research Design

3.1. Research Methodology

3.2. Object and Case Selection

3.3. Data Collection

4. Case Analysis

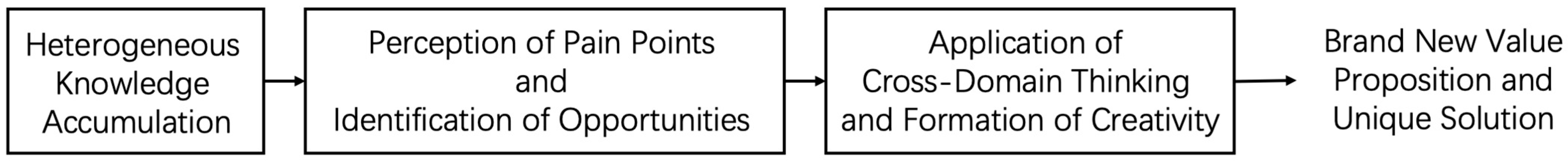

4.1. Analysis of the Formation Process of Novelty in Original Business Model Innovation

4.1.1. Encoding and Conceptualization Process

4.1.2. Replication Logic Validation and Theoretical Construction

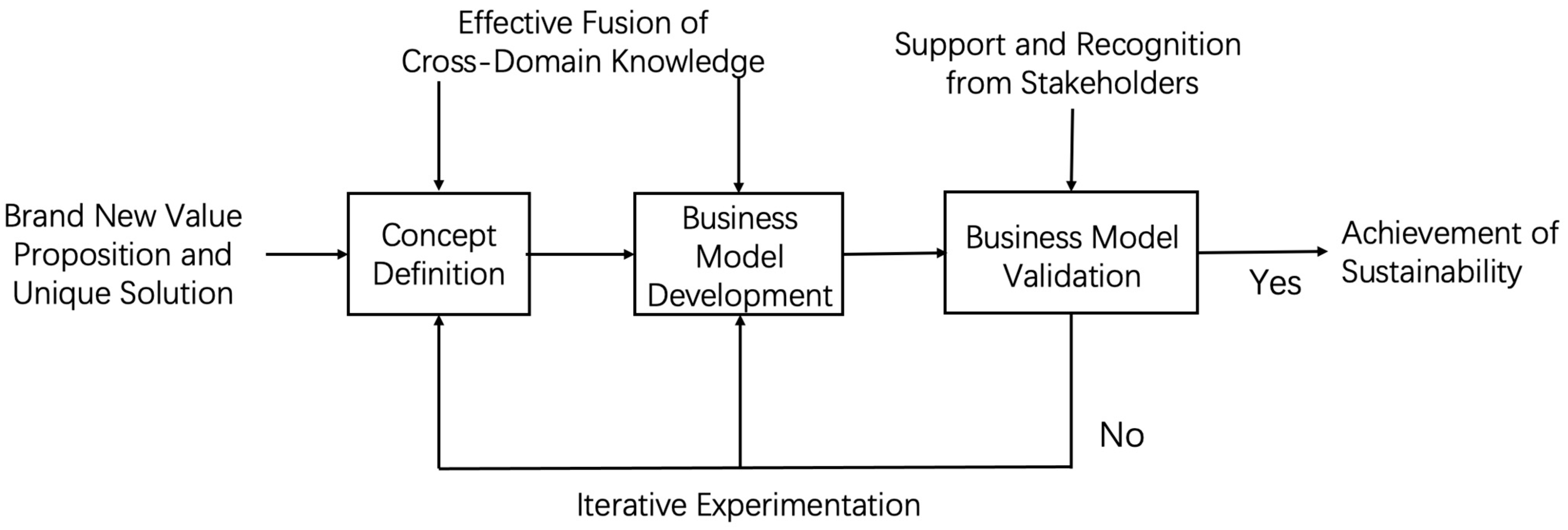

4.2. Analysis of the Formation Process of Sustainability in Original Business Model

4.2.1. Coding and Conceptualization Process

4.2.2. Replication Logic Validation and Theoretical Construction

5. Research Summary

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holtstrom, J. Business model innovation under strategic transformation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 34, 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Creating value through business model innovation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z. Research on the Antecedents of Business Model Innovation: Perspectives of Decision Logic and Organizational Learning. Manag. Rev. 2022, 34, 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Yu, J. Review and Prospect of Research on Business Model Innovation. Soft Sci. 2022, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xie, J. A Review of Research on Original Innovation. Philos. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2004, 25, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dai, S.; Lu, Z.; Tong, X.; Chen, W. Research on the Relationship between Drivers of Original Innovation and Innovation Performance. Res. Manag. 2017, 10, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Qureshi, I.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Q. Corporate social responsibility and disruptive innovation: The moderating effects of environmental turbulence. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1435–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Yu, C. On the Process and Governance Mechanism of Original Innovation in China. J. Cap. Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 4, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.; Gao, S. Mechanism Research on Enhancing Original Innovation through Employee Orientation. Res. Manag. 2022, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yang, J. Current Situation and Review of Theoretical Research on Original Innovation in Enterprises. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2013, 33, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, J.; Mazursky, D.; Solomon, S. Templates of original innovation: Projecting original incremental innovations from intrinsic information. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 1999, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. Multi-level Structural Innovation of Entrepreneurial Firm’s Business Model: A Case Analysis of Opal Polymers based on Strategic Entrepreneurship. China Ind. Econ. 2018, 11, 174–192. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante, S.; Kesting, P.; Ulhoi, J. Business model dynamics and innovation: Reestablishing the missing linkages. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Pistoia, A.; Ullrich, S. Business models: Origin, development and future research perspectives. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiolaa, M.; Agostinib, L.; Grandinetti, R. The process of business model innovation driven by IoT: Exploring the case of incumbent SMEs. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 103, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, J. How does the Application of Disruptive Technologies Create Value Advantage?—Based on the Perspective of Business Model Innovation. Econ. Manag. 2019, 3, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Garcia, M. Sustainable Business Models: Integrating Environmental and Economic Sustainability. Sustain. Manag. 2023, 15, 78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Jing, R.; Dong, M. Business Model Innovation Process: A Case Study on the Construction of Core Elements. Manag. Rev. 2019, 31, 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Zhao, Z. Antecedents of Business Model Innovation: Research Review and Prospects. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2017, 39, 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Ricart, J.E. Competitiveness: Business model reconfiguration for innovation and internationalization. Manag. Res. 2010, 8, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavetti, G.; Rivkin, J.W. On the origin of strategy: Action and cognition over time. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ma, S.; Zeng, L. Research on the Linkage of Space Elements in Business Model Innovation. Manag. J. 2020, 1, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.; Schindehutte, M.; Allen, J. The entrepreneur’s business model: Toward a unified perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, M.J.; Johnson, M.W.; Nair, H. New business models in emerging markets. Eng. Manag. Rev. IEEE 2014, 42, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yan, X.; Zhang, S.; Rao, W.; Zeng, L. Construction and Mechanism of Business Model Innovation Process: A Study Based on Grounded Theory. Manag. Rev. 2020, 32, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, S.; Doff, B. The Startup Owner’s Manual: The Step by Step Guide for Building a Great Company; K&S Ranch Press: Pescadero, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Yang, J.; Hu, X. How Does Business Model Innovation Shape the Differentiation of Business Ecosystem Attributes?—A Cross-Case Longitudinal Study and Theoretical Model Construction Based on Two Startups. Manag. World 2021, 37, 88–107+7. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Yang, Y. Unleashing Business Model Innovation in Digital Reconstruction: The Power of Strategic Flexibility. Res. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2022, 42, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Deng, Y. Review and Prospects of Business Ecosystem Research. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2020, 23, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Johnson, R.B. Exploring Disruptive Business Models in the Digital Age. J. Bus. Innov. 2023, 20, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Burford, N.; Shipilov, A.V.; Furr, N. How Ecosystem Structure Affects Firm Performance in Response to a Negative Shock to Interdependencies. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 22, 613–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Heng, L. The “jungle”, history, and approach road of the grounded theory. Sci. Res. Manag. 2020, 41, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Cao, Y. Case Study Method: Theory and Examples—Katherine Eisenhardt’s Collection of Papers, 4th ed.; Peking University Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Gong, X.; Zhang, M. Comparative Study of Case Study Methods by Yin, Eisenhardt, and Pan—From the Methodological Perspective. Case Stud. Rev. Manag. 2018, 11, 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kazanjian, R.K.; Drazin, R. A stage-contingent model of design and growth for technology based new ventures. J. Bus. Ventur. 1990, 5, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; Zhu, G., Translator; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Labianca, G.; Gray, B.; Brass, D.J. A grounded model of organizational schema change during empowerment. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, D. Formation Process and Dynamic Evaluation of New Business Models. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2015, 12, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Perry-Smith, J.E.; Mannucci, P.V. From creativity to innovation: The social network drivers of the four phases of the idea journey. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2017, 42, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Gao, D.; Song, J. Entrepreneur Industry Experience, Resource Integration, and Business Model Innovativeness. East China Econ. Manag. 2021, 35, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Lu, L.; Liu, J. Business Model Innovation and Cross-border Growth of Enterprises in the Context of “Internet Plus”: Model Construction and Cross-case Analysis. Res. Manag. 2021, 42, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Q.; Yu, X. The Logic of Cross-border Disruptive Innovation by Enterprises in the Internet Era. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 3, 156–174. [Google Scholar]

| Company Name | City Project Initiation | Year | Core Business | Characteristics of Original Business Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Beijing | 2014 | Time-sharing Rental Technology Service Provider | The first time-sharing rental technology service provider that generates its primary revenue from data |

| A2 | Beijing | 2012 | Second-hand car trading service provider | Financing leasing model based on SaaS services |

| A3 | Beijing | 2014 | Car-sharing service | Unique light-asset + heavy-operation car-sharing model |

| A4 | Beijing | 2013 | O2O e-commerce platform for new cars | The first online-to-offline integrated new car e-commerce platform |

| A5 | Beijing | 2014 | C2C platform for used car transactions | The first C2C used car trading platform |

| A6 | Beijing | 2014 | Shared bicycles | The first shared bicycle operation comp |

| Problem | Enterprise | Case Data | Phenomenon Definition | Conceptualization | Categorization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Process of Novelty | A1 | The short-term rental car service available by the hour on the roadside in the United States is very convenient, while in China, renting a car is difficult and the rental process is cumbersome and lengthy. | Renting a car in China is inconvenient compared to his experiences. | Perception of pain points. | Opportunity identification. |

| With 16 years of data mining experience, he has gained insights into the travel data behind the car rental industry. | Data mining experience with his expertise in the car rental industry. | Heterogeneous knowledge reservoir. | Knowledge accumulation. | ||

| As a technology service provider in the car-sharing industry, he provides technical services to car-sharing companies and positions value acquisition as the data behind the travel domain. | Applies data thinking to the car rental domain. | Application of cross-border thinking. | Formation of creativity. | ||

| A2 | He has served as the Executive Vice President of a car rental company and has experience in automotive finance, used cars, and other businesses. The team members come from different fields such as the Internet and software development. | Experience in car rental, finance, used cars, Internet, and software development. | Heterogeneous knowledge reservoir. | Knowledge accumulation. | |

| Based on his experience, he felt that the used car market was in a very poor state, extremely fragmented, with a lack of information systems and chaotic internal management among used car dealers. Young people have a strong demand for cars but lack the financial ability to purchase them in full. Information asymmetry creates a value gap in vehicle sales. | Based on his personal experience in purchasing used cars, he has identified several areas of dissatisfaction. | Perception of pain points. | Opportunity identification. | ||

| He provides comprehensive business services to car dealers based on a SaaS system, ensuring precise data matching. Additionally, he introduces the concept of automotive finance and launches new car Internet financing and leasing services based on the analysis of backend data from used car dealers. | Applies internet, software services, and financial thinking to the used car domain. | Application of cross-border thinking. | Formation of creativity. |

| Formation Process | Case Data | Enterprise |

|---|---|---|

| Heterogeneous Knowledge Accumulation. | Having struggled in the automotive industry for 13 years, the interviewee has worked in various departments including management services, sales, and financial management. They have also created an automotive finance platform and possess experience in internet development. Additionally, they have received an MBA education from Peking University Guanghua School of Management. | A3 |

| A graduate in engineering, with nearly 20 years of experience in the automotive industry, well-versed in the realm of the internet, and having studied management and economics. | A4 | |

| The founder has accumulated rich experience in internet product development and operations. The three co-founders each possess over 10 years of experience in automotive industry operations and management, aftersales service system management, and application development. | A5 | |

| Passionate about cycling, the founder has been involved in various ventures including mountain bike online rentals, high-end bicycle financing, second-hand bicycle trading platforms, distribution of smart wearable devices, and cycling tourism. The entrepreneurial team also possesses experience in mobile app development. | A6 | |

| Perception of Pain Points and Identification of Opportunities. | The field of mobility services is still in its infancy in China, and users’ flexible demands are not being met. The “light asset + heavy operation” B2P model is worth exploring. | A3 |

| Automobile manufacturers face both inventory backlog and challenges in purchasing cars in third-tier and below cities. | A4 | |

| Painful experiences in selling cars have led to the awareness of issues in the second-hand car market, such as lack of regulations, lack of transparency, lack of integrity, and price manipulation. | A5 | |

| Over the course of four years in university, they lost five bicycles. Not having a bicycle was very inconvenient for them. | A6 | |

| Application of Cross-Domain Thinking and Formation of Creativity. | We draw inspiration from “Ctrip” to create a platform that gathers small- and medium-sized car rental companies. We will independently develop car connectivity devices and build a unified app platform for numerous small-scale car rental companies online, while providing standardized and specialized services offline. | A3 |

| Our goal is to become a car Internet company that brings together various aspects of car life. In third- to sixth-tier cities, we will connect with car manufacturers and primary dealerships on the upper end and channel partners on the lower end. By integrating the upstream and downstream of the new car industry through automotive e-commerce, we will establish a complete ecosystem and create a closed-loop new car e-commerce platform. | A4 | |

| Using an internet-based approach, we will construct a C2C platform for second-hand car transactions, reducing costs associated with intermediaries and eliminating expenses related to physical spaces. This platform will meet the expectations of buyers and sellers in terms of price and quality. | A5 | |

| To address the issue of transportation difficulties, we can implement a bicycle-sharing system combined with password locks. Users can access the unlocking password through a mobile app, enabling them to use the bicycles at any time and return them by locking them again. | A6 |

| Problem | Enterprise | Case Data | Phenomenon Definition | Conceptualization | Categorization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Generation Process | A1 | The difficulties in software, hardware, and data management and data analysis were overcome through repeated attempts, resulting in the provision of a free solution for time-sharing leasing. This helped partners achieve an operational model of “time-sharing leasing, pay-as-you-go, self-service throughout, and on-demand return”, and later generated profits through data acquisition from traffic. | The company attempted various approaches to determine the final operating model. | Iterative attempts at cross-domain knowledge integration | Concept definition |

| To successfully operate time-sharing leasing, the participation of multiple parties is required, including vehicle dealers, original equipment manufacturers, platforms, electrical equipment companies, operating enterprises, and local resource providers. The operation is challenging, and the hardware system relies on components from various regions worldwide, with assembly and testing conducted in Beijing. | Multiple parties participated, and procurement and integration were carried out in multiple locations. | Iterative attempts at cross-domain knowledge integration | Business model development | ||

| The “sharing economy” has experienced explosive growth without encountering significant difficulties, with customers actively participating. The data generated between partners and consumers ensures their loyalty to the platform. With the increasing number of customers, the company has attracted investment from multiple investors and has a promising future in terms of profitability. However, the growing prospects also bring competitive pressure from new and potential competitors. | The customer base grew rapidly, and the customers showed genuine loyalty to the company, indicating promising future profits. This attracted the attention and support of investors. | Support and recognition from stakeholders | Business model validation | ||

| A2 | While providing SaaS services to the used car industry, the company discovered different needs among small and large used car dealers. After repeated exploration, they decided to launch different products for these dealers. | After repeated attempts, the company successfully identified two types of products that catered to the diverse needs of their target market. | Iterative attempts at cross-domain knowledge integration | Concept definition | |

| Collaborating with financial institutions, the company created an Internet-based automotive finance service model primarily focused on “1-year long-term rental + final payment to purchase.” In 2019 and 2020, the company delved into the digital transformation of the automotive industry and acquired comprehensive service providers in automotive supply chain warehousing and logistics, automotive trading platforms, ERP system providers for automotive dealers, and automotive freight information and channel service platforms. This gradually formed a digital ecosystem for the automotive circulation field. | The company also explored integration with various industries and formats, ultimately establishing a unique digital ecosystem service model. | Iterative attempts at cross-domain knowledge integration | Business model development | ||

| In 2016 alone, the number of car dealers using their SaaS system increased from over 200 to more than 4000. In 2017, 70–80% of used car dealers nationwide used their system, with large-scale dealers accounting for as high as 95%. The stickiness of the platform is strong, and with the improvement of service models, there is vast room for future growth. The company was listed on the “Global Rising Unicorn” list by PitchBook, a global data research institution in Silicon Valley, in 2017 as an automotive new retail and new finance platform. | With the rapid growth of the customer base, high adoption rates, and strong customer loyalty, the company has significant room for expansion and has gained recognition in the industry. | Support and recognition from stakeholders | Business model validation |

| Formation Stage | Formation Elements | Case Data | Enterprise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept definition | Iterative attempts at cross-domain knowledge integration | They conducted extensive research and iteratively designed a SaaS software service system for both B2B and B2C. | A3 |

| They went through different stages, from an information model to a transaction model, and then focused on selling cars, forming an “Internet + automotive industry” that caters to car buyers, with an all-in-one O2O model combining information, shopping, a marketplace, and city stores. | A4 | ||

| Since the establishment of their company, they have been on an adventurous journey, overcoming various challenges. Eventually, they developed a virtual consignment model that allows car owners to sell directly to buyers, eliminating intermediaries and ensuring fair transactions. Their platform provides services such as on-site inspections, valuation, and after-sales support. | A5 | ||

| Based on previous business attempts and campus surveys, they quickly identified a shared bicycle solution. Starting from campuses, they collected unused bicycles, refurbished and registered them, and equipped them with QR codes that integrate with their mobile app for unlocking and retrieval using a password lock. | A6 | ||

| Business model development | Iterative attempts at cross-domain knowledge integration | After multiple explorations, the following points have become clear: 1. The cars are sourced from small- and medium-sized rental companies. 2. The focus is on creating a seamless car rental experience anytime and anywhere, with car delivery within 10 min. 3. Cars can be returned at any location, and the platform handles the cumbersome post-rental tasks. 4. The initial focus is on establishing locations in Beijing before expanding nationwide. | A3 |

| Online, they distribute information tailored to the needs of individual consumers (C-end), while for businesses (B-end), they provide comprehensive dissemination from precision to breadth. They gradually integrate the internet with traditional industry by combining online information dissemination, offline guidance, in-person car delivery, and maintenance services into a closed-loop system. | A4 | ||

| They have made detailed preparations for the three core aspects: car sourcing, transaction transfer, and after-sales service. All car sources come from real individuals and undergo 249 professional inspections. They also provide full guarantees throughout the transaction process. | A5 | ||

| Implementing the idea of shared bicycles has faced many challenges. These include addressing issues such as bike theft, key-lock correspondence, the disparity between bike placement on campuses and the lack of user growth in orders, and finding solutions to the problem of bikes going missing without being returned. Each problem requires deep analysis, continuous exploration, and attempts to find practical solutions. | A6 | ||

| Business model validation | Support and recognition from stakeholders | They secured two angel investments and established over 50 locations in Beijing. User growth has been rapid, and although the company has not yet reached profitability, monthly revenue has doubled, validating their business model and customer experience. | A3 |

| They have formed an O2O closed-loop system through a large online comprehensive automotive marketplace and city stores spread across the country. The first batch of eight city stores have been operating successfully for a year with favorable conditions. The plan is to expand to 1000 city stores nationwide in the future. | A4 | ||

| The business model has proven to be attractive, quickly accumulating a large number of car sources after the launch. Within five months, they became the market leader in Beijing, with monthly sales of 300 cars. | A5 | ||

| They successfully launched and operated in Beijing’s universities, gaining recognition from investors. In 2016, their business rapidly expanded to over 20 universities in Beijing and other cities such as Wuhan and Shanghai. In September 2016, with the start of the academic year, they achieved a daily order volume of 400,000 orders. | A6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, G.; Ji, X.; Zhang, A. Novelty and Sustainability: The Generation Process of Original Business Model Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914182

Jiang G, Ji X, Zhang A. Novelty and Sustainability: The Generation Process of Original Business Model Innovation. Sustainability. 2023; 15(19):14182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914182

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Guihuang, Xuehong Ji, and Aonan Zhang. 2023. "Novelty and Sustainability: The Generation Process of Original Business Model Innovation" Sustainability 15, no. 19: 14182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914182

APA StyleJiang, G., Ji, X., & Zhang, A. (2023). Novelty and Sustainability: The Generation Process of Original Business Model Innovation. Sustainability, 15(19), 14182. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914182