Abstract

Communities and businesses continue to experience the effects of climate change as global temperatures rise and extreme weather events become more frequent. In the United States (US), the public sector has traditionally been responsible for mitigating these risks; however, engaging the private sector is crucial, given industrial impacts on and vulnerability to climate change. Private-sector mitigation and adaptation efforts are critical in the Great Lakes Region due to aging infrastructure as well as its economic, environmental, and political importance in the US and Canada. This study explores private-sector resilience efforts in three Great Lakes cities to identify opportunities and trends that could inform climate resilience strategies in the region. Climate-related commitments and actions of nine major firms in Toronto, Chicago, and Cleveland are evaluated in relation to seven climate resilience criteria on a five-level maturity scale from January to May 2022. The results indicate a moderate level of maturity, with efforts mainly at facility and community levels of engagement. Overall, this study suggests that major firms participate in climate resilience efforts, but to a limited extent, and may have varying priorities that affect the initiatives they pursue. This study could contribute to advancing climate resilience efforts in the public and private sectors from regional to global levels.

1. Introduction

Climate change is becoming increasingly evident due to the occurrence of both acute and chronic hazards, such as increased extreme weather events and rising global temperatures and sea levels [1]. The public sector has led climate adaption and mitigation efforts through urban planning and regulatory changes. However, it has been observed that local plans often fail to integrate smoothly with one another due to poor plan alignment, leading to increased physical and social vulnerabilities [2]. In addition, the rising costs of natural disasters coupled with the decreasing capital in government bodies mean that there is a need to engage other key players in the fight against climate change impacts [3]. In many ways, the participation of private-sector organizations is the next step required to close the climate resilience gap.

The private sector dominates many industries affected by climate risks, including agriculture, shipping, mining, real estate, and tourism, and can help address impacts through financial investments, technological developments, and human resources. Yet, there are several common barriers against its participation. Many organizations cite a lack of resources and incentives for long-term planning or a lack of knowledge related to climate change adaptation. Further, despite the widespread acknowledgment of the potential consequences of a changing climate, some organizations have attributed their lack of participation to skepticism regarding the severity and urgency of climate impacts [4,5]. As such, while the awareness of climate risks should translate to a need to adapt or mitigate those risks, this has not yet been realized [5].

The scope of this study is focused on the Great Lakes region of North America, as the area faces increased vulnerabilities due to its geography, economy, and infrastructure [6]. There have been notable increases in water levels in the past few years, as well as slight increases in average surface water temperatures [7]. The Great Lakes basin holds a population of approximately 30 million people in the US and Canada [7]. The lakes help to support the fishing, tourism, and shipping industries that have been impacted by the changes in water level, precipitation, and temperature. However, if these risks can be managed, the Great Lakes could also serve as a climate haven or refuge due to its abundance in freshwater. The lakes account for approximately 84% of surface freshwater in North America and 21% of surface freshwater globally [7]. Consequently, the region serves as an important location of research for climate adaptation and mitigation efforts, especially in relation to how private participation can improve community resilience, given that the fate of businesses and the local communities are largely dependent on the status and environmental conditions of the Great Lakes.

This study explores the current state of private-sector climate resilience based on the efforts of nine major companies in Great Lakes cities to identify opportunities and trends that could inform climate resilience strategies in the region’s receiving communities. A climate resilience maturity matrix was developed and applied to evaluate the maturity of the private-sector climate-related commitments and actions in three Great Lakes cities: Chicago, Toronto, and Cleveland. These cities were selected as cases to represent the region based on evidence of more advanced engagement in climate resilience and the availability of related data from their previous resilience efforts. Nine major companies based in those cities were then identified and their corporate efforts were evaluated. The average climate maturity scores of each company were compiled and analyzed for patterns across the region. These results were used to advance recommendations for encouraging broader resilience efforts.

The rest of this paper is outlined as follows: Section 2 provides a literature review on climate resilience in the Great Lakes region and the justifications for the selection of cities and companies. This is followed by Section 3, which summarizes the research approach, data collection, and analysis. Section 4 presents the key findings, and Section 5 describes the implications of the results. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the study, discusses limitations, and provides future research directions.

2. Background

To prepare for the study, the literature from four general categories was reviewed: (1) drivers and barriers for private-sector participation in resilience efforts; (2) growth opportunities for cities with increased climate resilience; (3) specific climate vulnerabilities of the Great Lakes region and its private organizations; and (4) existing resilience initiatives in the Great Lakes region as a basis for selecting cities as cases.

2.1. Drivers and Barriers to Private-Sector Participation in Resilience Efforts

Economic drivers are common for private-sector resilience efforts. For example, in studying the real estate industry, Teicher [8] found that the most proactive firms regarded climate resilience as a competitive advantage. Climate adaptation measures, such as retrofitting buildings for better flood protection, were perceived as good selling points, while the potential for climate risks to interrupt business was perceived as a severe liability. A study by Boulatoff et al. [9] noted that firms which participated in the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX) emissions reduction program—a voluntary regulatory program with legally binding emission reduction targets—saw financial and stock improvements within the first year of joining. This was supported by Gans and Hintermann [10], who added that performance improved both during the announcement period and when environmental regulation was expected. In general, many private organizations see climate risk mitigation as a financial opportunity.

However, other drivers motivate change. Besides improving stock market value, voluntary adaptation efforts, such as the CCX program, can help prepare organizations for future legislation, and to enhance their business strategies and innovate products and services so that they may emerge as industry climate leaders in the future [10]. In addition, the collective impact of climate change imparts changes to other aspects of businesses, such as their supply chains, customer base, employee health and safety, and employee commute. For example, extreme weather events can cause supply shortages, damage to transportation infrastructure, and climate migration [11]. Although these effects can translate to financial risks for the business, they are also social drivers, given that they can principally impact the growth and livelihood of the local community.

Despite the growing need for climate mitigation and adaptation, the private sector is lagging in its participation due to certain barriers and opposing motivators. In a study by Chin et al. [5] regarding the hospitality and tourism industry in the Great Lakes region, some organizations considered climate risks as advantageous to their businesses. For example, rising temperatures can increase traffic to beaches and water recreation activities. Regions experiencing longer shoulder seasons may see increased traffic to indoor spaces due to milder temperatures. Chin et al. [5] described how some hospitality businesses plan to expand the length of their patio season or invest in large, heated tents for outdoor events to adapt to the longer spring and fall shoulder seasons. These short-term benefits were seen as advantageous by some interviewees in their study, especially because there was a lack of incentives from the local, state, and federal governments to pursue long-term business preparedness and adaptation [5]. The lack of incentives has also led to resilience strategies that consist of simply avoiding investments in high-risk areas altogether, contributing to further social inequity [8].

The ignorance of the severity and probability of climate risks is also a major barrier. Goldstein et al. [1] identified several blind spots in most private-sector resilience strategies, such as not understanding the magnitude of climate risks and adaptation costs, the need for adaptation strategies beyond direct operations, and nonlinear climate risks. These blind spots are indicative of how drivers rooted in financial motives can lead to superficial resilience plans with the organization capping its own investments and research [8]. Overall, private firms all around the world have noted being discouraged from participating in resilience planning due to inadequacies in the financial and educational resources available and due to a perceived absence of local government efforts.

2.2. Growth Opportunities for Climate Resilience

There is an opportunity to cross the barriers through public–private cross-sector collaboration. Public officials can provide training and subject matter experts, while private organizations can help by improving the capital allocation of resilience investments [3]. Collaborative partnerships can help cities steer private-sector resilience efforts, while the private sector can benefit from having a greater voice in urban planning [12]. For example, poor plan coordination can lead to private organizations being zoned to vulnerable regions, which can affect the resources needed for climate adaptation [2].

Local government can also better measure their resiliency and vulnerability using scorecards and assessment tools. Berke et al. [2] developed a resilience scorecard to measure the physical and social vulnerabilities of a community and how well local plans are mitigating them. Loerzel and Dillard [13] assessed 56 resilience frameworks to develop an inventory to assess resilience measurement and to search for frameworks that can be applicable for a particular system or hazard. Such existing tools and approaches could be utilized or adapted to suit public- and private-sector efforts.

It is important, however, for both sides to avoid investing in reactive measures, as this can potentially hurt the community. For example, climate insurance is a form of public–private-sector collaboration that can help communities bounce back from disaster events, but if the underlying risk factors remain, the costs of the insurance could be passed onto the local citizens instead through increased premiums [14]. To improve community resilience, private-sector efforts and investments should be focused on proactive measures and preventative responses.

2.3. Climate Vulnerabilities of the Great Lakes Region

Resilience efforts in the Great Lakes region are critical due to its economic, environmental, and political importance, as well as its high vulnerability to climate change. The abundant supply of freshwater in the region supports almost a quarter of Canada’s agricultural production and 7% of America’s farm production [7]. Its gross regional product is USD 4.1 trillion, representing nearly one-third of the US economy [15]. Due to their size, the lakes themselves have a significant effect on regional climate. They moderate the temperature as they absorb heat in warmer months and radiate heat to the atmosphere in colder months, leading to cooler summers, warmer winters, and longer growing seasons in the surrounding area [16]. However, the same characteristics that have allowed the region to prosper have also caused it to be vulnerable to climate risks.

While, historically, water levels have risen and fallen in natural patterns, climate change is causing more volatility in these cycles. Rising temperatures reduce ice cover and enhance evaporation, leading to lower lake levels and the depletion of the lakeshore [17]. On the other hand, increases in average rainfall and extreme storm events have led to more runoff and flooding, which not only threatens infrastructure, but also increases the pollution risk from cities with a combined sewage outflow and surrounding Superfund toxic waste sites [18]. The region’s vulnerabilities are exacerbated by aging infrastructure, poor wastewater management, and its economic reliance on agriculture, ports, and tourism [19]. It also has the potential to suffer from other risks faced by coastal cities, including high asset exposure, decreasing land area, and insufficiencies in facilities and infrastructure to address social vulnerabilities following climate migration [20].

2.4. Existing Resilience Initiatives in the Great Lakes Region

The 100 Resilient Cities program, founded in 2013 and sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation, was intended to aid cities around the world to develop urban resilience plans. Cities had to demonstrate their commitment to urban resilience, their engagement process with different community actors, and plan to address vulnerable populations [21]. Toronto and Chicago were the only two Great Lake cities included in the program. The Toronto Resilience Office was funded by a direct grant from the program. In 2019, the office unveiled Toronto’s first resilience strategy, created with input from 8000 citizens and 80 participating organizations. Thirty-three of them were nonprofit organizations, thirteen were companies, and five were universities. The report outlined three focus areas with 27 action items. The action items listed key partners, most of which were from the public sector [22]. In general, Toronto’s resilience planning indicated some private-sector engagement, but was primarily supported by city organizations.

Most of the literature we found that addressed private-sector participation in climate adaptation efforts in the Great Lakes region focused on the city of Chicago. Besides being a member of the 100 Resilient Cities program, Chicago hosted a voluntary environmental regulation program before through the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX) emission reduction program [9]. Its extensive history in resilience yielded an abundance of publicly available information. The city has experienced many extreme weather events in the past, which may explain its increased interest in climate resilience. It has diverse economic assets and is home to approximately 400 major corporations. Chicago’s resilience strategy, known as Resilient Chicago, seeks to address socioeconomic disparities, critical infrastructure, and community preparedness. Like Toronto’s plan, Resilient Chicago listed collaborating partners for each action item that helped to identify the private organizations that engaged in resilience planning [23]. Chicago also has a separate climate action plan that focuses on climate risks and mitigation, specifically with regard to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. There are some mentions of private investment and insurance, but it does not call out specific businesses [24]. Besides the city’s urban planning reports, private-sector engagement was identified through the participating organizations list of the CCX program. The program had more than 400 members, including Amtrak (Washington, DC, USA), Eastman Kodak (Rochester, NY, USA), and Sony Electronics Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA) [25].

In Cleveland, temperatures are rising three times faster than elsewhere in the US, leading to increased heat waves, flooding risks, and storm events [26]. The city also ranks high in poverty, food insecurity, and air pollution, with these issues affecting people of color and low-income people the most. The Mayor’s Office of Sustainability was established to spearhead these issues. The office has hosted annual sustainability summits since 2009 to engage the city’s key players [27]. In 2013, the climate action plan was created, which outlined the city’s engagement process, climate action goals, and monitoring of progress. The plan was guided by the Climate Action Advisory Committee that consisted of several private organizations, such as MetroHealth, KeyBank, and Eaton Corporation, and resident leaders, who participated through neighborhood workshops. The report also mentioned collaborations with private sector and industry leaders to build a smarter city through smart grid technologies and to improve access to public parks through providing more trails. Overall, Cleveland has a substantial climate adaption plan in place and is committed to working with both the private sector and local citizens to improve community resilience.

2.5. Summary of Review and Research Gaps

The literature on private-sector engagement in climate resilience efforts largely consisted of qualitative, interview-based studies in specific industries and their approach toward climate change impacts, specifically hospitality, tourism, and real estate industries. While there is extensive research on the common barriers and drivers of climate change participation, these did not discuss specific public–private collaboration or engagement strategies. This study contributes toward narrowing the literature gaps by providing a framework to evaluate private-sector climate resilience efforts. The companies selected for evaluation represent key industries of the Great Lakes region not previously researched, including manufacturing, finance, food production, and energy. The maturity evaluation and analysis suggest trends and opportunities that could inform public–private engagement strategies.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study Cities

To explore the extent to which the private sector has engaged in resilience efforts, we focused on three Great Lake cities as case studies, based on the extent of their resilience initiatives. Toronto and Chicago were both part of the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities program, while Cleveland has social conditions and land use patterns that increase its vulnerability to climate change. As a result, all three cities developed extensive resilience plans. In a study by Klein et al. [12], a positive correlation was identified between a city’s adaptation progress and the likelihood of the private sector being included in resilience efforts. As such, studying cities with greater climate adaptation progress could illuminate the potential of private-sector interests and participation in community resilience. Figure 1 shows the location of the selected cities in the Great Lakes region.

Figure 1.

Location of case study organizations (map adapted from: Great Lakes Map (printable-maps.blogspot.com, accessed on 15 September 2023)).

3.2. Case Study Organizations

Within each of the selected cities, we focused on major organizations as benchmarks, considering their impact and influence on the region. The criteria considered included the industry, size, financial performance, and location of headquarters. The organizations had to be part of or related to one or more of the key industries in the area, as identified by the Council of Great Lakes, which included manufacturing, agriculture, mining, energy, tourism, shipping and logistics, education and health, and finance. These industries were significant to the economy and employment of the region. The organizations also had to be large and high-performing, likely to have higher contributions to climate change, but also greater influence to address those impacts. However, this also meant that the companies usually had many diverse locations. To ensure a stronger connection between the organization and the region, the last criteria was that the global or North American headquarters were located in one of the three cities. Three major companies from each city were evaluated for a total of nine. Table 1 shows the companies with their corresponding industry, headquarters, size, and financial performance.

Table 1.

Description of companies selected for climate resilience maturity evaluation.

Engagement in climate resilience was evaluated for the nine firms using a maturity matrix, based on relevant, publicly available data, including corporate sustainability reports, policies, plans, press releases, and news articles. The results were then averaged based on company, criteria, and city to identify potential trends.

3.3. Maturity Matrix

Maturity models and matrices have often been used as tools for organizational assessments and improvements, based on the evaluation of organizational capabilities across a progression of growth [28,29,30]. Maier et al. [28] maintain that capability maturity matrices, or maturity grids, have been overlooked somewhat in the academic literature compared to more widely disseminated capability maturity models (CMMs), such as those developed for specific processes in software engineering disciplines. In contrast with CMMs, maturity matrices typically take the form of an assessment grid, designed to be more widely applicable and flexible as a diagnostic tool for a range of organizations in any industry [28]. As such, a maturity matrix is well-suited for the research purpose of guiding organizational strategies and can be applied as a means to consistently evaluate the status of private-sector efforts. An organization can be assessed across a progression path represented by levels of maturity from an initial suboptimal level to an optimal level [28].

While the Smart Mature Resilience (SMR) Project developed a resilience maturity model to evaluate resilience measures in European cities, this tool is specifically focused on municipal policies and initiatives, and no existing maturity scale applicable for our purpose of assessing private-sector involvement in climate resilience was found in the literature. Following the framework for maturity grids proposed by Maier et al. [28], we incorporated the underlying rationale of Williams and Greenwood’s [31] maturity matrix for corporate social responsibility and Veleva and Eckenbecker’s [32] Lowell Center for Sustainable Production Indicator Framework, as well as climate mitigation and adaptation criteria from the ISO 14090:2019 standard on Adaptation to Climate Change, and adapted the structure and criteria from the SMR model for city resilience for a private-sector-focused audience. The matrix design decisions are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Private-sector climate resilience maturity matrix design decisions 1.

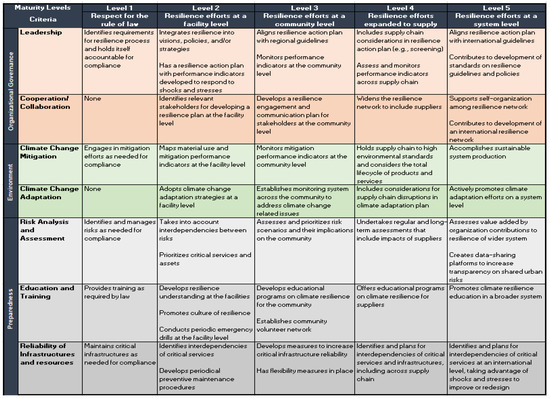

The resulting matrix defined seven criteria in three evaluation categories across five levels of maturity (Table 3). Consistent with Veleva and Eckenbecker’s [32] framework, the levels in the matrix were defined based on the scope of climate resilience efforts and the extent that such efforts were extended outward beyond the organization’s own facilities and across their sphere of influence. Consistent also with Williams and Greenwood’s [31] approach, the maturity scale ranged from 1 to 5, with level 1 representing the lowest “floor” level of basic legal compliance and respect for the rule of law, level 2 representing resilience efforts within an organization’s facility or site(s), and subsequent levels representing resilience efforts expanded increasingly in scope beyond the facility at the community level (level 3), across the supply chain (level 4), and at a broader international or system level (level 5). Thus, each stage progression indicated a scope expansion for the organization’s effort and sphere of influence.

Table 3.

Maturity level description and rationale.

The evaluation categories included (1) organizational governance, (2) the environment, and (3) preparedness. The category of organizational governance included criteria for leadership and for cooperation/collaboration. This measured the scope and alignment of resilience action plans and the extent of the organization’s resilience network. Climate resilience requires coordination within and between the private and public sector. As described by Chan et al. [33], addressing climate change means that the entire world needs to undergo a socioeconomic transformation. This would not be possible without goal coherence, which would be supported by using standardized guidelines and greater collaborations.

The environment category included the criteria of climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation. This measured the actual programs and activities of resilience plans to see how they addressed climate impacts. Climate change mitigation involves efforts to prevent or reduce global warming impacts, usually achieved through addressing the source of carbon release. On the other hand, climate change adaptation involves efforts to address the existing effects or to prepare for expected effects [34]. Both strategies are necessary to manage climate risks, as current mitigation efforts are inadequate in this regard [35].

The last category, preparedness, identified criteria for risk analysis and assessment, education and training, and the reliability of infrastructures and resources. This measured how aware and ready organizations were with regard to climate change. Resiliency requires the ability to identify and prepare for all sorts of unexpected stressors [21]. A comprehensive risk management program and a learning culture can help with the identification of climate risks, while increased reliability and flexibility measures for infrastructure and resources can help with the aftermath of a climate event. The resulting climate resilience maturity matrix is shown below in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Private-sector climate resilience maturity matrix (adapted from Smart Maturity Resilience [36]).

4. Results

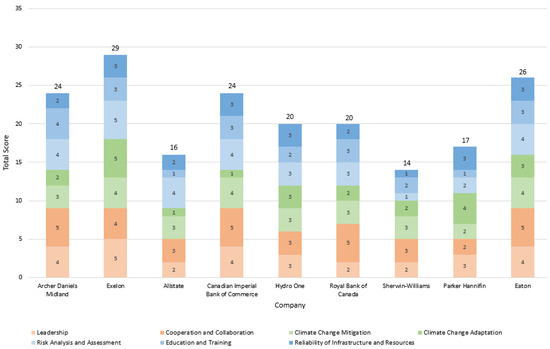

Data and documentation from each of the selected companies were examined in relation to the seven criteria in the matrix in order to evaluate the maturity of their climate resilience efforts in relation to individual criteria as well as overall. Out of a possible total score of 35, the average total score was 21.7 (62%), with a standard deviation of 5.1. Most companies fell within one standard deviation of the average, with the exception of Exelon, with a score of 29, and Sherwin-Williams, with a score of 14.

Exelon displayed system-level thinking for many of its climate resilience initiatives and programs. For example, its risk management process incorporated a climate change scenario analysis and identified greenhouse gas mitigation, transition, and adaptation risks. The process also considered its supply chain through a semiannual supplier criticality and risk review, in which the organization would work with all suppliers on the watch list to develop corrective action strategies [37]. In contrast, Sherwin-Williams was observed to be more at the compliance level, where there existed an environmental plan at each facility, but there were no efforts disclosed on the specific climate analysis or identification of critical services and assets [38].

Comparing the scores from city to city, the average score for Chicago was 23 (66%), while Toronto’s average was 21.3 (61%), and Cleveland’s was 19 (54%). The overall evaluation for the nine firms is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Average climate resilience maturity scores by company.

Common trends appeared between companies in the same or similar industries. CIBC and RBC both showed high maturity for collaboration and cooperation through their memberships and support for multiple international initiatives. Both CIBC and RBC were part of the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) and the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI). CIBC was also the first Canadian bank to join the Center for Climate-Aligned Finance, while RBC was part of the net-zero banking alliance. However, unlike manufacturing or chemicals industries, the majority of carbon emissions for the finance industry fell under scope three [39]. For context, as defined by the EPA, scope one emissions are direct GHG emissions from sources controlled by the organization; scope two emissions are indirect GHG emissions from the purchase of electricity, steam, heat, or cooling; and scope three emissions are the result of all activities from assets not owned or controlled by the organization, but for which the organization has an indirect impact in [40]. The most common scope three emissions in the finance industry were financed emissions, which are GHG emissions from the organizations that the financial institutions invest in. Thus, even if there were extensive efforts in place to prevent and mitigate their direct emissions, they would not be addressing their greatest impacts unless they were to implement and follow stricter climate policies for their clients [39]. This was reflected in their scores for climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation.

Exelon, Hydro One, and Eaton represented the energy industry and, on average, showed higher maturity for climate resilience. This could be because climate risks have much more direct impacts on energy infrastructure. For example, the sustainability reports of all three companies mentioned improving grid resiliency and conducting climate-related risk assessments. In addition, given the type of service, there was greater interaction between the organizations and their communities. This was reflected in how almost all of their scores for each criterion were at least a three. The only exception to this was the education and training criteria for Hydro One, as their training was more internally focused [41].

On the other hand, organizations in the manufacturing industry—Sherwin-Williams and Parker Hannifin—showed lower maturity and more focus at the facility level. Neither of these organizations had published goals to reduce scope three emissions, and climate change resiliency seemed to be an aftereffect to their initiatives. For example, Parker Hannifin’s highest score was for climate change adaptation because the company utilized dual sourcing to protect its supply chain. However, this was not in response to identifying potential climate disruptions, but just as a general solution to the present supply chain risks [42,43]. This was reflected by its scores in the other criteria, which were primarily at a compliance or facility level. Similarly, Sherwin-Williams did not appear to have conducted any climate scenario analyses or climate risk assessments, but their environmental and safety management systems included requirements for periodic drills, which could inadvertently help its employees prepare for climate change impacts, such as extreme weather events [44]. A potential driver for climate resilience was integration into other operational or business priorities.

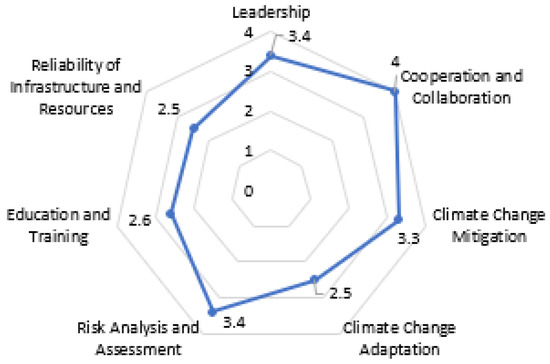

Trends were noted across the maturity categories. The highest average level of maturity was related to organizational governance, comprised of leadership and cooperation efforts. All of the companies evaluated were, to some extent, part of a resilience network, whether through direct collaboration or organizational memberships. In addition, there appeared to be a growing trend to align climate goals with science-based targets, with three of the nine companies conducting this publicly. Figure 4 depicts the average climate resiliency maturity scores by criteria.

Figure 4.

Average climate resilience maturity scores by criteria.

5. Discussion

Comparing scores from city to city, the average scores for Chicago and Toronto, which were both Rockefeller 100 cities, were higher than that of Cleveland. This was not entirely surprising, considering the resources and structure provided by the Rockefeller 100 initiative. It suggested value in the Rockefeller approach for advancing resilience, which involved creating a single point of contact to drive city-wide resilience efforts through a chief resilience officer, helping communities to engage with private and civil society stakeholders to build a resilience strategy, and connecting them with a network of partners and technical experts to help them put strategy into practice [45].

When comparing scores for companies in the same or similar industries, firms in the energy sector indicated higher maturity, with an average score of 25, followed by firms in the finance sector, with an average of 22. Regarding the energy sector, this could reflect the extent of more direct impacts associated with climate risks on energy infrastructure. In the finance sector, existing partnerships and sector-specific initiatives may have been a contributing factor in resilience efforts. Both CIBC and RBC were engaged in multiple programs, including PCAF and UNEP FI. Firms in the manufacturing sector indicated lower maturity, with an average score of 15.5. These companies appeared to focus efforts somewhat more internally, including on more limited and localized leadership, the assessment of risk, and efforts toward climate mitigation.

Overall, mitigation efforts appeared to be more common than adaptation efforts. This indicated that organizations approach climate change with a preventative mind set, as seen by programs such as Sustainability by Design [38] and public policy advocacies [46]. However, many of these mitigation goals were long-term efforts that could take decades to see substantial results from. For example, CIBC set a net-zero emission goal for 2050. No information was available for initiatives to address their current impacts, especially from financed emissions [47]. Similarly, ADM implemented energy efficiency projects and achieved the first carbon-neutral milling operations, but did not disclose any information regarding how they planned to protect their supply chain, which is especially important for the food production industry [48]. Given that the Great Lakes region is especially vulnerable to climate risks, it is necessary for organizations to prepare for existing climate effects, while also setting up mitigation strategies. Fortunately, it was observed by Bateman and O’Connor [35] that current mitigation efforts can make future adaptation easier and less costly. Identifying this gap in climate efforts and understanding the connection between mitigation and adaptation could potentially guide future attempts to drive private climate resilience efforts.

As for preparedness, all organizations had a risk management system in place. The differences lay in whether their risk analyses specifically considered climate change. Only the two manufacturing firms, Sherwin Williams and Parker-Hannifin, did not appear to have a climate scenario analysis or climate risk identification in place. Five of the nine companies included considerations of impacts to their supply chain, with high maturity organizations screening and auditing their suppliers. On the other hand, the organizations appeared to be much lower in maturity for the other two criteria. Four companies had some form of climate education opportunities for their communities, such as the CIBC Climate Center or the Eaton India Foundation. Two did not have any information available, and only one organization extended resiliency training to their suppliers. Five of the companies contributed improvements to their infrastructure or assets for increased reliability, yet none discussed plans to address interdependencies of critical services beyond their facilities. With the aging infrastructure in the Great Lakes region [19], the deficiencies in preparedness could likely be a key area of concern for resiliency.

The maturity matrix was informed by the literature review and related maturity frameworks. It was successful in this regard and was generally suitable and adequate for evaluating the efforts of the selected companies, yet there were some limitations observed during the process. Maturity was evaluated through the scope of the climate resilience efforts. However, there were instances where available information was incomplete, or where programs related to the same criterion had varying levels of maturity for criterion indicators in the matrix. For example, Parker Hannifin employed dual sourcing, which increased the reliability of its resources. However, no information was available regarding insurance for infrastructure [42]. Similarly, RBC stated plans restricting financing for sensitive sectors and to invest USD 500 billion in sustainable financing by 2025 [49], yet news reports have revealed that the company also significantly increased its financing for fossil fuels [50]. Future research may benefit from the consideration of actual performance data and results, if available, to evaluate the overall impact of climate resilience efforts.

Further, while the landscape may be changing in light of emerging ESG reporting directives, there is currently no overarching standard for voluntary reporting on sustainability. As Schneider et al. [51] also found, sustainability-related reporting and voluntary initiatives vary in format, content, and approach, and, thus, can be difficult to evaluate and compare. In addition, it should be recognized that assessments via a maturity matrix are by nature a somewhat subjective process, as Maier et al. [28] concluded. While we developed and applied a maturity matrix to evaluate a number of organizations through an external lens, the use of the matrix as an internal tool would not be subject to the same challenges, and could be valuable for organizations seeking further engagement and continual improvement in climate resilience.

6. Conclusions

Private-sector engagement can lead to the development of products and services that reduce climate-related financial and human impacts, providing business advantages while enhancing and protecting human health and well-being in the communities in which they operate. The existing literature has already identified common barriers and motivators to climate change efforts. The maturity model presented in this study supported the evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of each organization’s plans and efforts based on seven criteria. While this study was exploratory, the results suggested that private-sector efforts in Great Lake cities may be lagging with regard to climate adaptation and preparedness for disruption, particularly in relation to education and training, and the reliability of infrastructures and resources. Overall, the results of the study suggested that major firms in the private sector were participating in climate resilience efforts, but, depending on their sector and location, had varying priorities that affected the initiatives they pursued, as well as varying place-based support structures for resilience efforts. For example, the energy companies indicated higher preparedness because improving their infrastructure was already a part of their operational goals. First and foremost, resilience efforts must be compatible with their business strategies.

Given the aging infrastructure in the Great Lakes region, the deficiencies in preparedness could likely be a key area of concern for resiliency. The involvement of private industry has immense potential in strengthening societal resilience through climate change mitigation actions that minimize nonrenewable energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, as well as in contributing to the regional adaptive capacity. Furthermore, it aligns with the self-interest of these organizations to fortify their own resilience to climate change. Organizations can gain a better understanding of potential climate impacts on their operations and align resilience efforts with their business strategies through comprehensive climate risk assessments. They can enhance their resilience, for example, by extending the timeframes considered in strategic planning to align with projected timescales associated with climate impacts, and by taking proactive, adaptive action where needed to address identified risks. A process for a periodic assessment using a maturity matrix or scorecard could be a useful tool to highlight gaps in preparedness and measure progress to improve resiliency.

The realization of the burgeoning climate risk to enterprises, their employees, and communities should translate into intrinsic incentives to directly contribute to community resilience. Strategies to increase the involvement of the private sector in community or regional climate resilience efforts include the development of regional public–private partnerships that incentivize engagement and collaboration through financial and nonfinancial means. This can include local tax incentives or grants to support participation, as well as capacity-building incentives through the sharing of expertise and knowledge among scientific, governmental, and industrial partners to raise private-sector awareness of climate-related risks and available options for adaptation. Such partnerships could also enable public–private collaboration on mutually advantageous research that supports technological innovation.

Limitations of the study included the small sample size and potential bias in the selection of cities and companies. These three cities were chosen based on their extensive resilience experience, which may be indicative of greater private-sector participation than typical. This was necessary, as the evaluations depended on publicly available information, but the companies selected may not be representative of private-sector efforts overall. Major firms’ levels of maturity may be higher than other organizations in the region. In addition, the companies selected may be involved in additional efforts that were not publicly disclosed. It is possible that these organizations may be engaged in climate resilience efforts that were not reflected in the available information, resulting in skewed maturity ratings.

Combining information from other studies on the barriers and motivators and the results from the maturity matrix could inform private-sector climate resilience strategies. As noted previously, the use of a maturity matrix through an external assessment lens is a somewhat subjective process. The use of the matrix internally as a diagnostic tool may offer additional benefits for organizations seeking further engagement and continual improvement in climate resilience. Private organizations have a large impact on their respective cities’ economy and resiliency, and in the case of the Great Lakes region, improving their participation could potentially help to elevate it from climate vulnerability to a climate haven. Public sector organizations could use the maturity matrix to identify potential collaborators and risks.

Although one limitation of the study was the small pilot sample size, there is an opportunity to identify trends within each city by expanding this research, focusing on organizations in a specific locale. There is also an opportunity to study trends within specific industries across the region. Lastly, future research utilizing a mixed-method research design that supplements document analyses with qualitative data, such as from surveys or interviews, could offer deeper insights on private-sector engagement across the region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L.G., J.L.S. and V.L.; methodology, L.L.G., J.L.S. and V.L.; formal analysis, V.L., L.L.G. and Y.S.A.; investigation, V.L. and L.L.G.; resources, L.L.G., J.L.S. and V.L.; data curation, V.L. writing—original draft preparation, V.L., L.L.G., Y.S.A. and J.L.S.; writing—review and editing, L.L.G., Y.S.A. and J.L.S.; visualization, V.L, Y.S.A. and L.L.G.; supervision, L.L.G. and J.L.S.; project administration, L.L.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Goldstein, A.; Turner, W.R.; Gladstone, J.; Hole, D.G. The private sector’s climate change risk and adaptation blind spots. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, P.; Newman, G.; Lee, J.; Combs, T.; Kolosna, C.; Salvesen, D. Evaluation of networks of plans and vulnerability to hazards and climate change: A resilience scorecard. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2015, 81, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarvis, M.H.; Bohensky, E.; Yarime, M. Can resilience thinking inform resilience investments? Learning from resilience principles for disaster risk reduction. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9048–9066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, G.; Spencer, A.; Tyson, A.; Funk, C. Why Some Americans Do Not See Urgency on Climate Change; Pew Research Center: 9 August 2023. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2023/08/09/why-some-americans-do-not-see-urgency-on-climate-change/ (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Chin, N.; Day, J.; Sydnor, S.; Prokopy, L.S.; Cherkauer, K.A. Exploring tourism businesses’ adaptive response to climate change in two Great Lakes destination communities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 12, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhoe, K.; VanDorn, J.; Croley Ii, T.; Schlegal, N.; Wuebbles, D. Regional climate change projections for Chicago and the US Great Lakes. J. Great Lakes Res. 2010, 36, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US EPA. Facts and Figures about the Great Lakes. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/greatlakes/facts-and-figures-about-great-lakes (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Teicher, H.M. Practices and pitfalls of competitive resilience: Urban adaptation as real estate firms turn climate risk to competitive advantage. Urban Clim. 2018, 25, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulatoff, C.; Boyer, C.; Ciccone, S.J. Voluntary environmental regulation and firm performance: The Chicago Climate Exchange. J. Altern. Invest. 2012, 15, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, W.; Hintermann, B. Market effects of voluntary climate action by firms: Evidence from the Chicago Climate Exchange. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2013, 55, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surminski, S. Private-sector adaptation to climate risk. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 943–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Araos, M.; Karimo, A.; Heikkinen, M.; Ylä-Anttila, T.; Juhola, S. The role of the private sector and citizens in urban climate change adaptation: Evidence from a global assessment of large cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 53, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loerzel, J.; Dillard, M. An analysis of an inventory of community resilience frameworks. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2021, 126, 126031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surminski, S.; Bouwer, L.M.; Linnerooth-Bayer, J. How insurance can support climate resilience. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 333–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Cooper, M.J.; Friedman, K.; Anderson, W.P. The economy as a driver of change in the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence River basin. J. Great Lakes Res. 2015, 41, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeton, A.M. Great Lakes. In Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Great-Lakes (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Alex, B. Rising Waters Threaten Great Lakes Communities. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2020/09/30/rising-waters-threaten-great-lakes-communities (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Gallagher, G.E.; Duncombe, R.K.; Steeves, T.M. Establishing Climate Change Resilience in the Great Lakes in Response to Flooding. J. Sci. Policy Gov. 2020, 17, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydersen, K. From Rust to Resilience: What Climate Change Means for Great Lakes Cities. Available online: https://www.minnpost.com/environment/2020/04/from-rust-to-resilience-what-climate-change-means-for-great-lakes-cities/ (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Mafi-Gholami, D.; Jaafari, A.; Zenner, E.K.; Kamari, A.N.; Bui, D.T. Vulnerability of coastal communities to climate change: Thirty-year trend analysis and prospective prediction for the coastal regions of the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Rockefeller Foundation. 100 Resilient Cities—The Rockefeller Foundation. Rockefeller Foundation. Available online: https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/report/100-resilient-cities/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- City of Toronto. Resilience Strategy. City of Toronto. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/services-payments/water-environment/environmentally-friendly-city-initiatives/resilientto/ (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- City of Chicago. Resilient Chicago. Available online: https://resilient.chicago.gov/ (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Makra, E.; Gardiner, N. Climate Action Plan for the Chicago Region, Metropolitan Mayors Caucus, NOAA, and U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit. Available online: https://mayorscaucus.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/RegionalCAP_Summary_Document_091521.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Chicago Climate Exchange. Members of CCX. Available online: http://www.chicagoclimatex.com/content.jsf?id=64 (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Sridhar, D. Climate Resiliency. Available online: http://www.clevelandnp.org/resilientcleveland/ (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Cleveland Neighborhood Progress. Request for Proposal for Development of Circular Cleveland Roadmap. Available online: http://www.clevelandnp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/RFP-for-Development-of-Circular-Cleveland-Roadmap.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Maier, A.M.; Moultrie, J.; Clarkson, P.J. Assessing organizational capabilities: Reviewing and guiding the development of maturity grids. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2011, 59, 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, T.; Rohner, P. Situational maturity models as instrumental artifacts for organizational design. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Design Science Research in Information Systems and Technology, Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 7–8 May 2009; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Asah-Kissiedu, M.; Manu, P.; Booth, C.A.; Mahamadu, A.-M.; Agyekum, K. An integrated safety, health and environmental management capability maturity model for construction organisations: A case study in Ghana. Buildings 2021, 11, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Greenwood, L. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility According to ISO 26000: The Pharmaceutical Industry; Department of Civil Engineering Technology, Environmental Management and Safety, Rochester Institute of Technology: Rochester, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Veleva, V.; Ellenbecker, M. Indicators of sustainable production: Framework and methodology. J. Clean. Prod. 2001, 9, 519–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Iacobuta, G.; Hägele, R. Maximising goal coherence in sustainable and climate-resilient development? Polycentricity and coordination in governance. In The Palgrave Handbook of Development Cooperation for Achieving the 2030 Agenda: Contested Collaboration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Adaptation to Climate Change—Principles, Requirements and Guidelines (ISO 14090). Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/68507.html (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Bateman, T.S.; O’Connor, K. Felt responsibility and climate engagement: Distinguishing adaptation from mitigation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 41, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resilience, S.M. Resilience Maturity Model. Available online: https://smr-project.eu/tools/maturity-model-guide/ (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Exelon. 2020 Exelon Corporation Sustainability Report. Available online: https://www.exeloncorp.com/sustainability/Documents/dwnld_Exelon_CSR%20(1).pdf (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Sherwin-Williams. The Sherwin-Williams Company—2020 Investor ESG Summary. Available online: https://s2.q4cdn.com/918177852/files/doc_downloads/esg/2021/06/SHW_2020_Investor.ESG.Summary.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Hodgson, C. Canadian Banks Double Financing of Highly Polluting Oil Sands. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/970e5b5d-74c7-4cc9-84a0-732da35769d5 (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- US EPA. GHG Inventory Development Process and Guidance. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/climateleadership/ghg-inventory-development-process-and-guidance (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Hydro One Limited. Announcing our Commitment to Net-Zero Greenhouse Gas Emissions by 2050. Available online: https://www.hydroone.com/about/energizing-ontario/blog/climate-change-goals (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Parker Hannifin. Parker Hannifin Sustainability Report: Enabling a Carbon Neutral Tomorrow. Available online: https://www.parker.com/portal/site/PARKER/menuitem.c17ed99692643c6315731910237ad1ca/?vgnextoid=a80b0ce599a5e210VgnVCM10000048021dacRCRD&requestedci=220438ca29928610VgnVCM100000e6651dacRCRD&vgnextcat=Sustainability&vgnextfmt=ES (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Parker Hannifin. Parker Commits to Achieving Carbon Neutral Operations by 2040, Advances Technologies that Enable a Sustainable Future—Parker Hannifin Corporation. Available online: https://investors.parker.com/news-releases/news-release-details/parker-commits-achieving-carbon-neutral-operations-2040-advances (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Sherwin-Williams. Building in the Good: 2020 Sustainability Report. Available online: https://s201.q4cdn.com/124745054/files/doc_downloads/sustainability_reports/2020_KB_Sustainability_Report_052821_Spread.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Berkowitz, M.; Kramer, A.M. Helping cities drive transformation: The 100 Resilient Cities Initiative. Interviews with Michael Berkowitz, president of 100 Resilient Cities, and Dr. Arnoldo Matus Kramer, Mexico City’s Chief Resilience Officer. Field Actions Sci. Reports. J. Field Actions 2018, 18, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Exelon. Exelon, Coalition of Power Companies Argue Before U.S. Supreme Court in Favor of Preserving EPA’s Authority to Regulate Power Plant Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Exelon. Available online: https://www.exeloncorp.com/newsroom/exelon-coalition-of-power-companies-argue-before-u-s-supreme-court-in-favor-of-preserving-epas-authority-to-regulate-pow (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. CIBC CDP Climate Change Response 2021. CIBC. Available online: https://www.cibc.com/content/dam/cibc-public-assets/about-cibc/corporate-responsibility/environment/documents/cibc-cdp-climate-change-response-2021-en.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Archer Daniels Midland. ADM-Announces-Industrys-First-Net-Carbon-Neutral-Milling-Operations. Available online: https://www.adm.com/en-us/news/news-releases/2021/8/adm-announces-industrys-first-net-carbon-neutral-milling-operations/ (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Royal Bank of Canada. Environment, Social and Governance (ESG): Performance Report 2021. Available online: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/_assets-custom/pdf/2021-ESG-Report.PDF (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Marsh, A. Royal Bank of Canada Faces Shareholder Vote on Climate Standards. Available online: https://financialpost.com/fp-finance/banking/royal-bank-canada-faces-shareholder-vote-on-climate-standards (accessed on 28 April 2022).

- Schneider, J.; Vargo, C.; Campbell, D.; Hall, R. An analysis of reported sustainability-related efforts in the petroleum refining industry. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2011, 44, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).