New Insights into the Layering Process of Urban Environment and Private Garden Transformations: A Case Study on the Bubbling Well Road Area in Early Modern Times, Shanghai

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

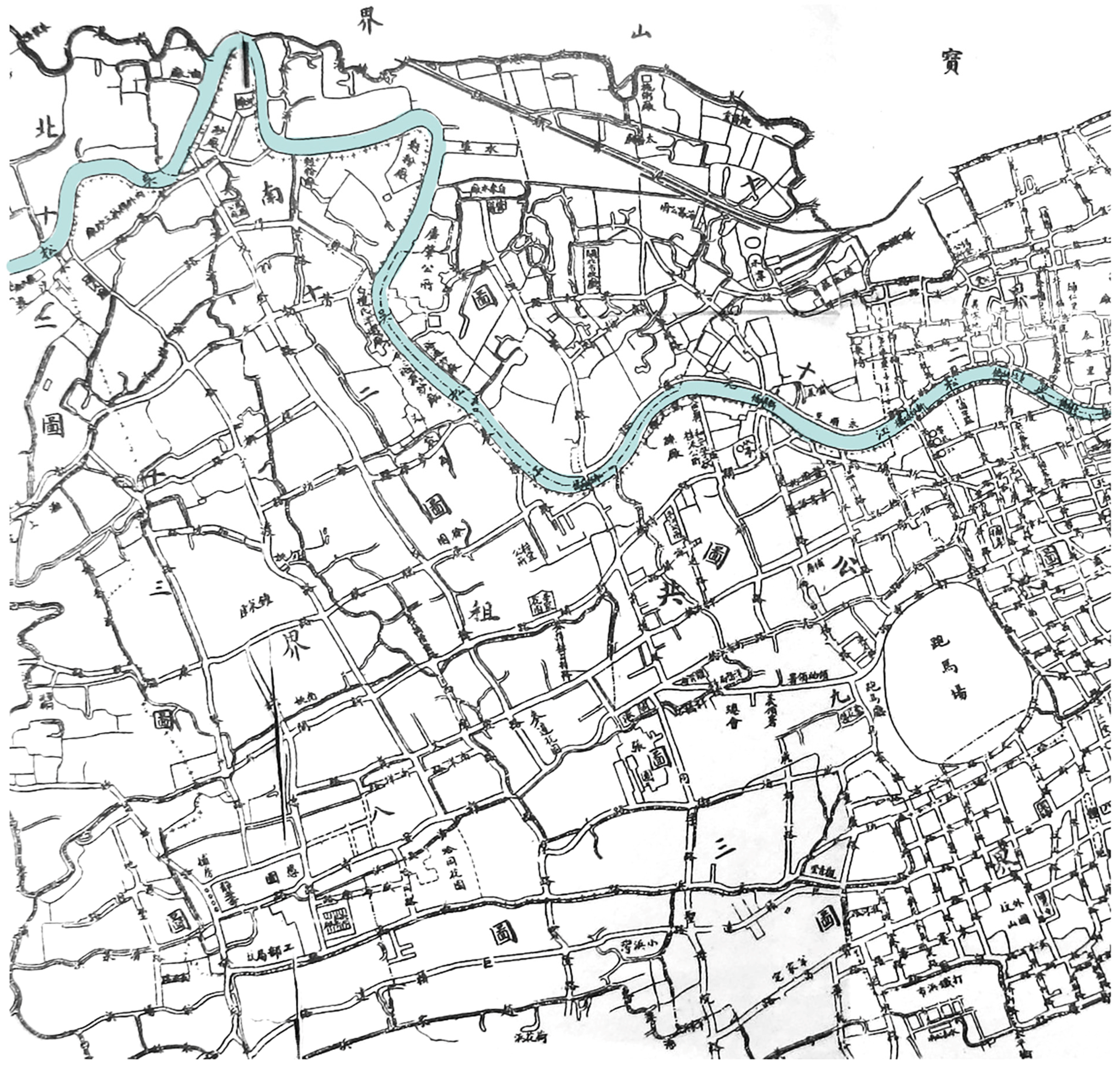

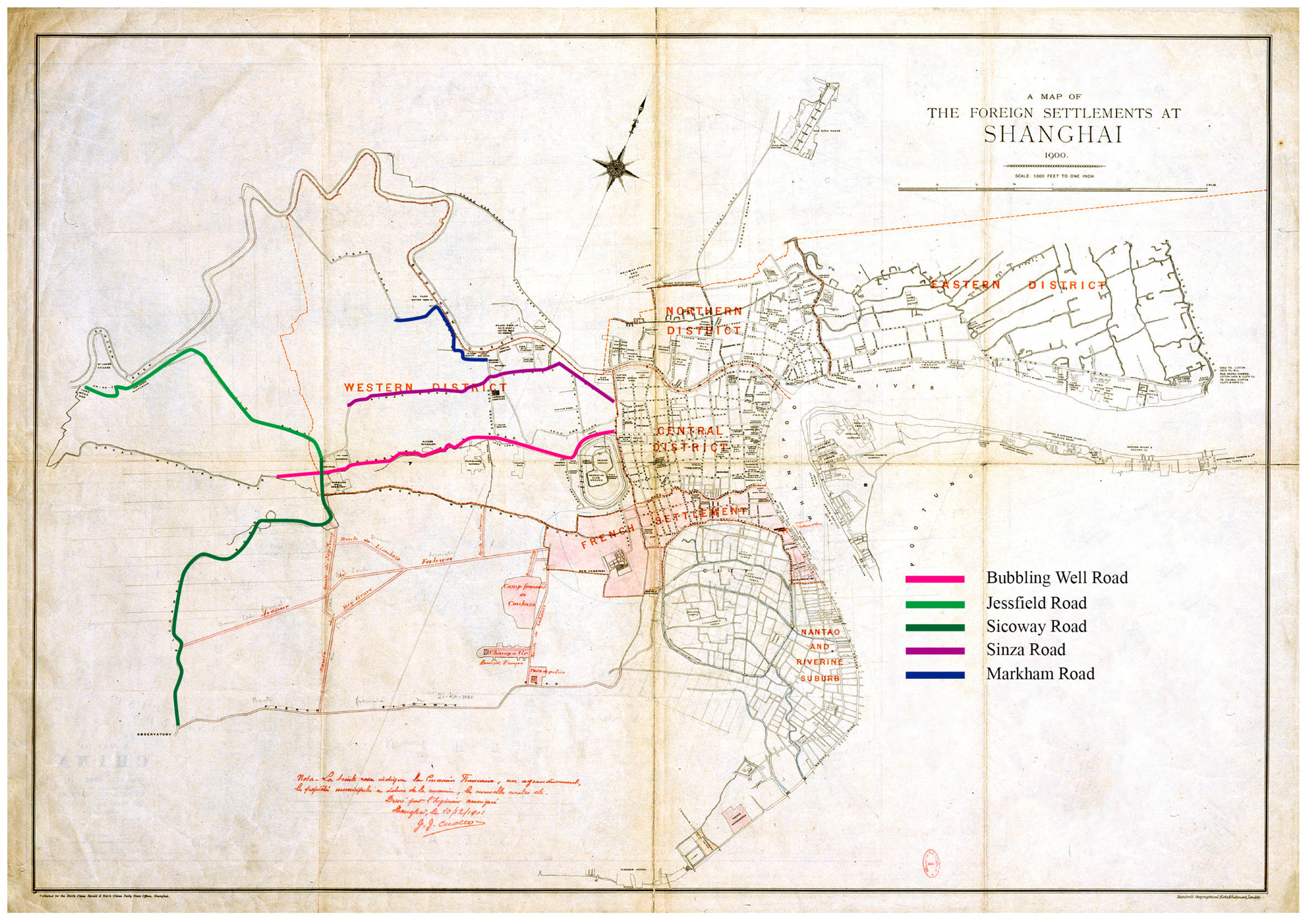

2.1. Study Area and Object

2.2. Research Framework

2.3. Materials and Sources

3. Results

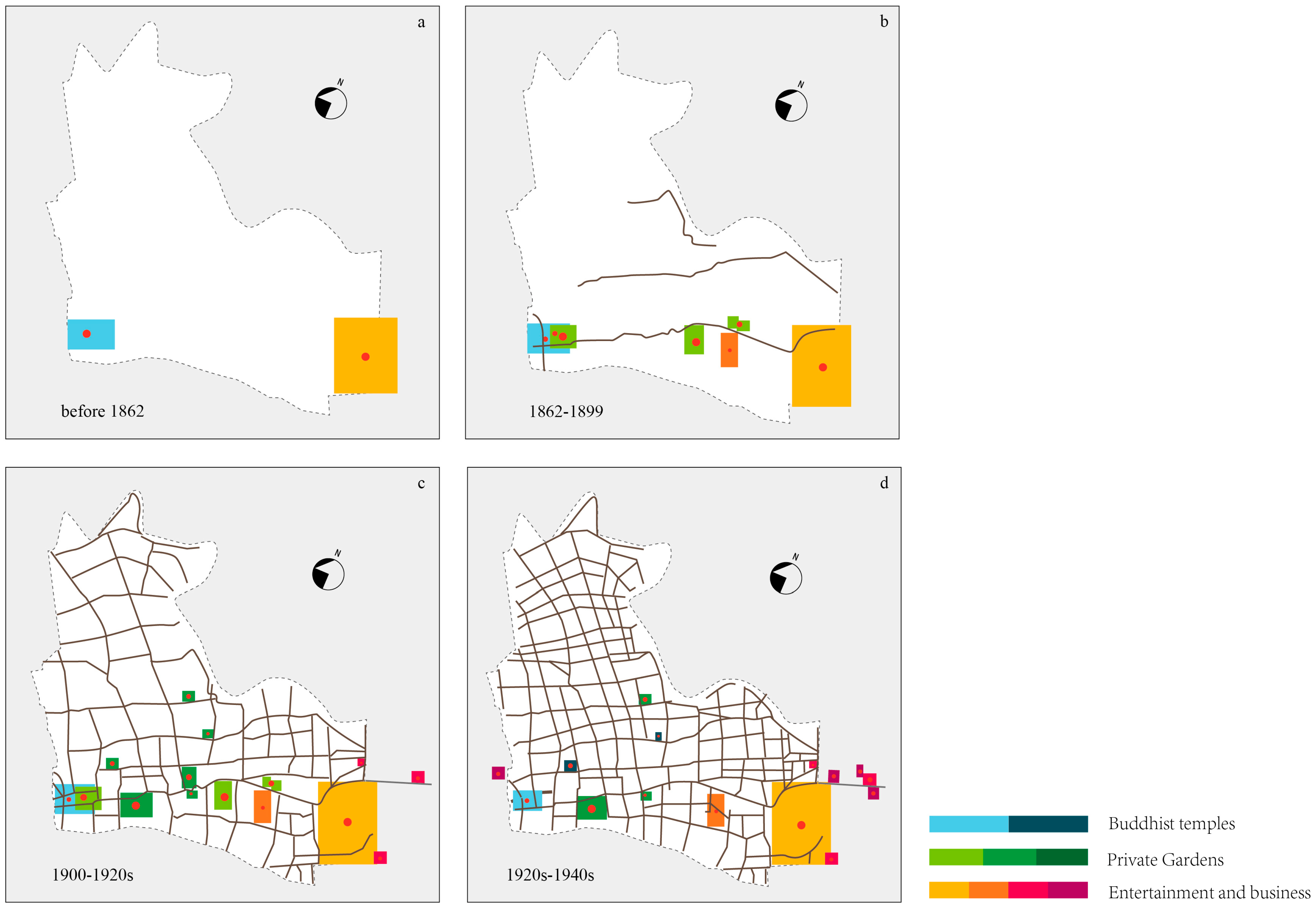

3.1. Development and Changes in Bubbling Well Road Area

3.1.1. Ancient Scenery and Temple Fair at Jing’an Temple (before 1862)

3.1.2. Formation of Urban Road Network (1862)

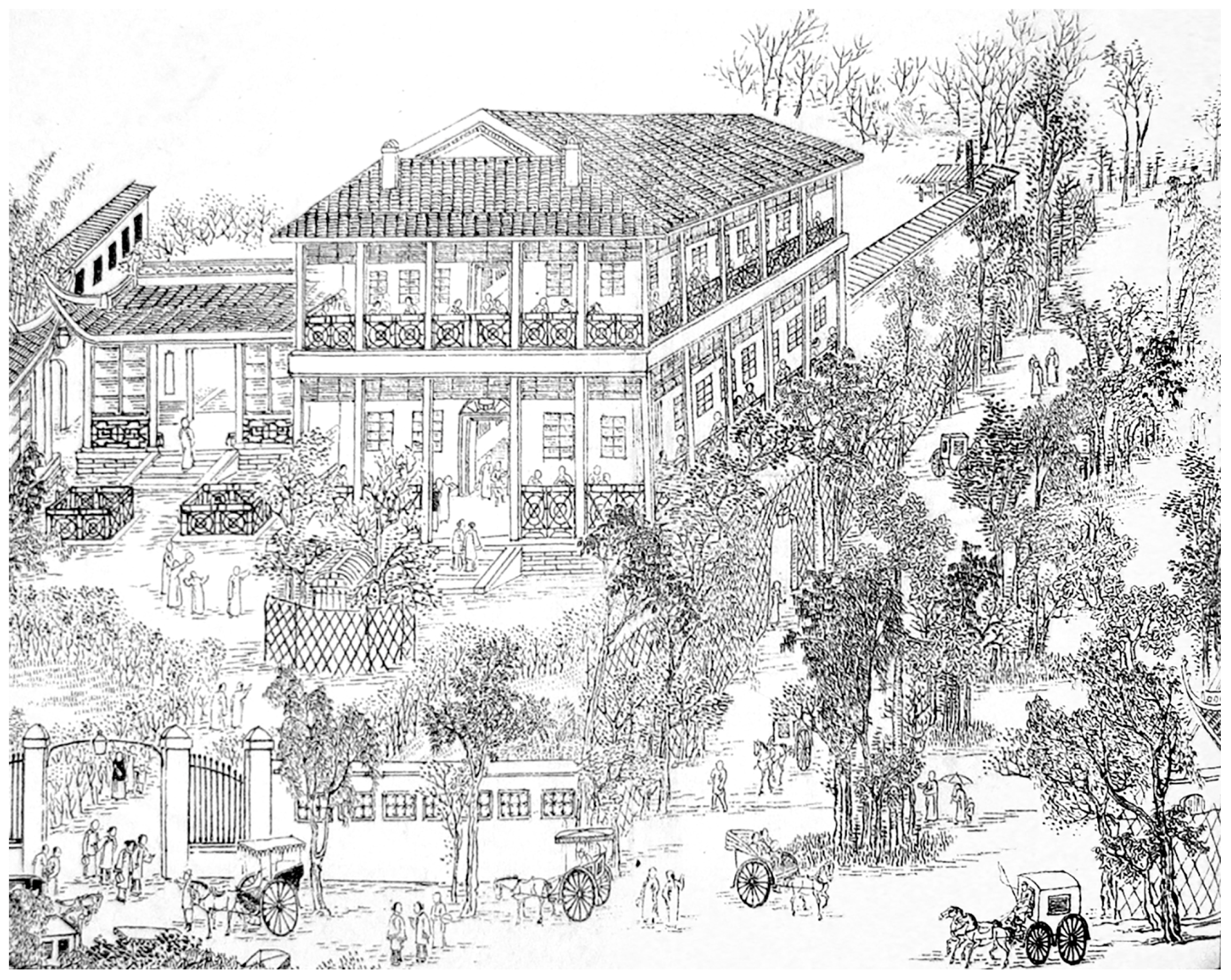

3.1.3. The Beginning of Urbanization (1862–1899)

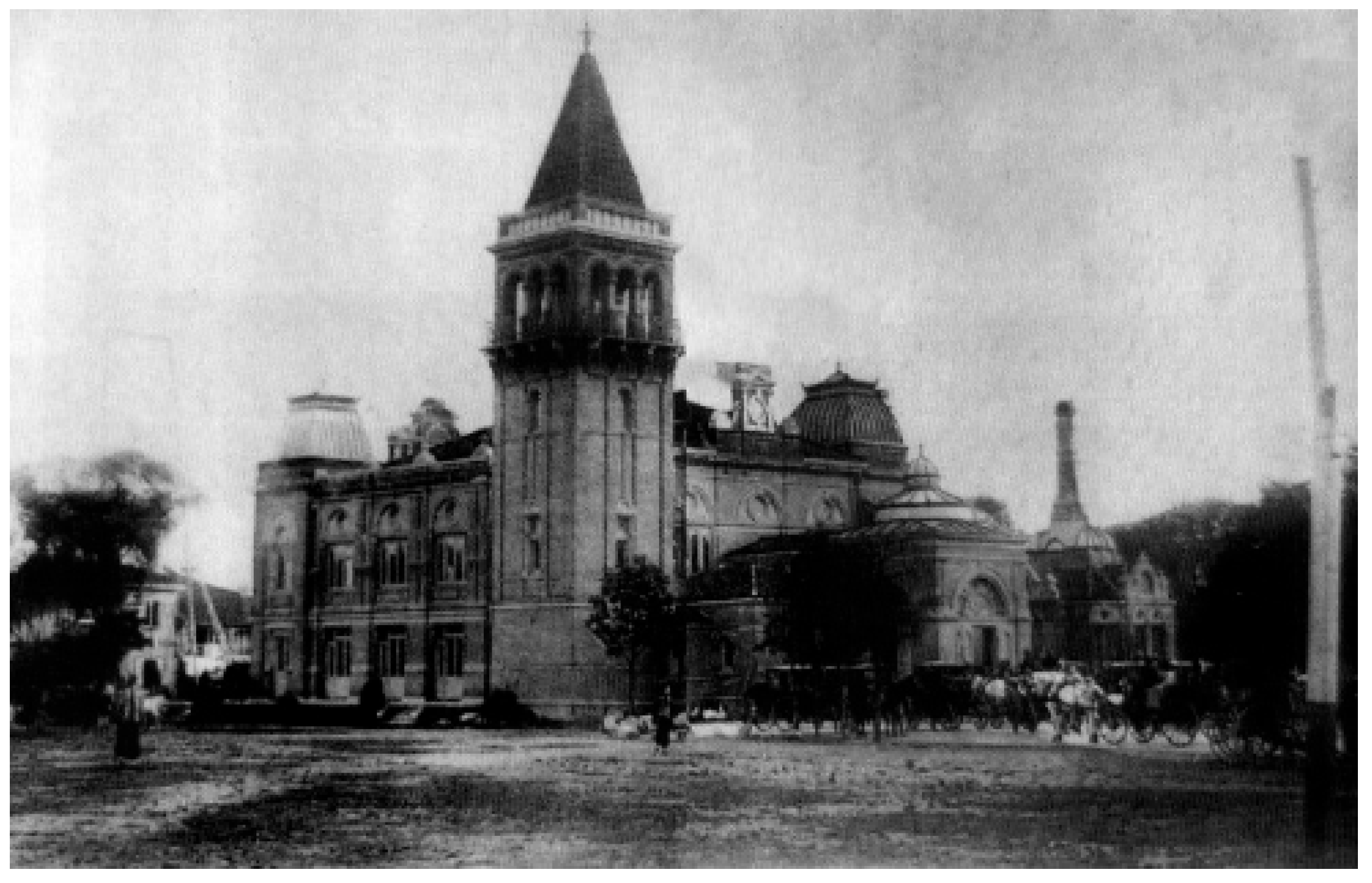

3.1.4. Repositioning towards the Urban Center (1900–1940s)

3.2. Evolution in Private Gardens along Bubbling Well Road

3.2.1. Dynamics of Profit-Oriented Private Gardens

3.2.2. From Private Gardens to Public-Affiliated Gardens

3.2.3. Revealing or Concealed Private Residential Gardens

4. Discussion

4.1. The Typical Stage of the Relationship between City and Garden in the Area around Bubbling Well Road

4.1.1. The First Stage: Suburban Areas and Places of Leisure (before 1862)

4.1.2. The Second Stage: Urban Road Construction and the Establishment of Profit-Oriented Private Gardens (1862–1899)

4.1.3. The Third Stage: Urbanization and the Formation of “Backyard Garden” in Concession (1900–1920s)

4.1.4. The Fourth Stage: Peak of Urbanization and Transition from “Backyard Garden” to Commercialization (1920s–1940s)

4.2. The Logic of Layering Process of Private Gardens and Urban Environment in Modern Shanghai

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, J.F. From Water Town to Metropolis: Evolution and Environment of the Modern Shanghai Urban Road System (1843–1949). Ph.D. Thesis, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, Z.Y. The Research on the Land Transaction, Land Price and Its Driving Mechanisms of Shanghai French Concession (1852–1872). Res. Chin. Econ. Hist. 2017, 2, 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.C.; Wen, Z.X. Installing, Gapping and Municipalizing: The North Railway Station Shaped in the Urban Process of Modern Shanghai. Archit. J. 2021, 02, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P. A Study on the Relationship between Municipal Construction and Transformation of Urban Space in the International Settlement of Shanghai; Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y. The Heart of Modern Shanghai: The Evolution of Function and Form in the Central District of the Shanghai International Settlement; Shanghai People’s Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, Z.Y. From Weidi Fishing Songs to Eastern Paris: A Study on the Urbanization Process of Modern Shanghai French Concession; Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.C. Beyond Neon Light: Everyday Shanghai in the Early Twentieth Century; Shanghai Classics Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in An Urban Century; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. In Proceedings of the Records of the General Conference 36th Session, Paris, France, 15 October–10 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Verdini, G.; Frassoldati, F.; Nolf, C. Reframing China’s Heritage Conservation Discourse. Learning by Testing Civic Engagement Tools in A Historic Rural Village. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.R.; Martinez, P.G. Lights and Shadows Over the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape: ‘Managing Change’ in Ballarat and Cuenca Through a Radical Approach Focused on Values and Authenticity. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbricatti, K.; Biancamano, P.F. Circular Economy and Resilience Thinking for Historic Urban Landscape Regeneration: The Case of Torre Annunziata, Naples. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceno, M.; Sanchez, A.; Tamayo, J.; Izquierdo, H.; Ponsot, E.; Ulloa, R.; Camacho, L. Historical layers of the urban landscape of Ibarra, Ecuador. Rev. Geográfica Venez. 2021, 62, 256–272. [Google Scholar]

- Picchio, F.; De Marco, R. Landscape Analysis and Urban Description of Bethlehem Historical Center: A Methodological Approach for Digital Documentation. Heritage 2019, 2, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Correlativity and Systematic Approach in Integral Conservation of Historic City: Understanding Historic Urban Landscape in China’s Context. City Plan. Rev. 2014, S2, 42–48+113. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.Z.; Han, F. Leipziger Baumwollspinnerei: An Outstanding Transformation of Industrial Heritage Site to Creative Cluster. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 3, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.P.; Zhang, X.C. Research on the Protection of Historical and Cultural Cities in the Perspective of Historic Urban Landscape: A Case Study of Daming Ancient City of Ming and Qing Dynasties in Hebei. Dev. Small Cities Towns 2019, 1, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, L.; Zhao, P.J.; Hu, Y.J.; Zhang, C.R. Theory of Layering Cognition and Integrated Conservation of Traditional Villages: Introduction of Historic Urban Landscape Approach. Urban Dev. Stud. 2021, 11, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, M.Y.; Zheng, W.J.; Ai, Y.; Li, G.F. The Interpretation of the Spatial-temporal Process of “Anchoring-Layering” Structure of Guilin Landscape City Historical Urban Landscape. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 3, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.Z. Landscape Approach for Urban Heritage Conservation: Review and Reflection of the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL). In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Conference of the Chinese Society of Landscape Architecture, Guiyang, China, 20–22 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Han, F.; Luo, J. Conservation Practice of Urban Historic Landscape in Germany: Case Study of Palaces and Parks of Potsdam and Berlin. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 6, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Ma, C.; Cao, K. Landscape Evolution and Layering Analysis and Heritage Value Identifying of Historic Urban Public Parks Under the Civic Cultural Perspective: A Case Study of Shaping Park in Chongqing. Urban Insight 2023, 8, 137–148+164. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Qu, Y. Brownfield Regeneration from the Perspective of Historic Urban Landscape: Azhal Park Case Study, Cairo. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2019, 8, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.L. History of Shanghai Urban Area; Academia Press: Shanghai, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Local Chronicles Office. Shanghai Ming Jie Zhi; Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press: Shanghai, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Member of the Compilation Committee of Shanghai Jing’an District. Jing’an District Chronicle; Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press: Shanghai, China, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai Jing’an District People’s Government. Shanghai Jing’an District Place Name Chronicle; Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press: Shanghai, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, J.X. Guide to Old Shanghai: Distribution Map of Roads, Institutions, Factories, and Residences; Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press: Shanghai, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Zhong, C. Complete Atlas of Shanghai Antiquated Maps, 2017; Shanghai Calligraphy and Painting Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.Y. Jing’an Temple Has Undergone Two Urban Development Changes over the Course of More Than a Hundred Years. Shanghai Real Estate 2019, 10, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.H.; Zhou, X.P.; Wu, Y.J. Research on Temporal and Spatial Evolution of Profit-Oriented Private Gardens in Modern Shanghai (1882–1949). Landsc. Archit. 2022, 3, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y. A Record of Visiting Jue Garden. Zhen Ge 1932, 2, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Doing Textual Research on Aili Garden. Hist. Rev. 2014, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.G. From the Segregation to Integration of the Chinese Residents with Foreign People. In Shanghai: Gateway to the World; Hong, Y., Ed.; Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press: Shanghai, China, 1989; Volume 4, pp. 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.H. The Implication of Shanghai-Style Gardens: Study on Private Gardens in Shanghai During the Republic of China; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Global News Editorial Department. Picture Daily; Shanghai Classics Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.W. Stable Urbanization: A Concept of Urbanization Quality from the Perspective of Population Migration. China Rural. Surv. 2012, 1, 2–12+21. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Cai, Z.; Fu, Z. Does the New-type Urbanization Construction Improve the Efficiency of Agricultural Green Water Utilization in the Yangtze River Economic Belt? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 64103–64112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, N. Booster or Killer? Research on Undertaking Transferred Industries and Residents’ Well-being Improvements. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, D.S. Rural-urban Income Distribution Effect of Land Supply: A Perspective of Imbalance Development of Urbanization. Nankai Econ. Stud. 2017, 2, 76–95. [Google Scholar]

| Type of Garden | Name | Owner | Duration of Existence | Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| profit-oriented private garden | Shen Garden | Li Yixian et al. | 1882–1893 | 0.80 |

| West Garden | Zhang Yicha et al. | 1887–1889 | — | |

| Yu Garden | tycoon Zhang Shi of Siming | 1888–1921 | 2.00 | |

| Zhang Garden | Zhang Shuhe | 1882–1919 | 4.10 | |

| Xu Garden | Xu Hongkui | 1883–1937 | 0.20~0.67 | |

| Affiliated gardens | McBain Garden (Garden of Majestic Hotel) | — | 1911–1930 | 4 |

| Jue Garden (South Garden) | The Jian brothers | 1916–Now | 6.67 | |

| Private residential garden | Aili Garden (Hardoon Garden) | Silas Aaron Hardoon | 1903–1948 | About 6.67–13.33 |

| Xi’s Family Garden * | Xi Exian | 1911 *–1937 | — | |

| Xin’s Family Garden | Xin Zhongqing | The end of the Qing Dynasty–1921 | — |

| Typical State | Time | Urban Environmental Characteristics | Main Anchor Points | Minor Anchor Point | Typical Stage Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State 1 | Before 1862 | Rivers crisscrossed farmlands and villages, presenting the picturesque scenery of rural areas in Jiangnan. | Jing’an Temple | A suburban tourist attraction has been centered around Jing’an Temple | |

| State 2 | 1862–1899 | Five military roads were constructed, along with the completion of Bubbling Well Road. Large garden villas and private residential gardens emerged on both sides, while the urban backdrop still maintained a natural countryside theme. | Shen Garden, West Garden, Zhang Garden, Yu Garden, Country Club | Jing’an Temple, represented by the residences and garden villas of Shao Youlian and Sheng Xuanhuai. | The profit-oriented private gardens built around Jing’an Temple have become new suburban attractions. Bubbling Well Road has strengthened the closeness between the Jing’an Temple area and the central district of the International Settlement. |

| State 3 | 1900–1920s | Bus routes were set up, and the area around Bubbling Well Road became a transportation hub. | The cluster of the public entertainment industry were represented by profit-oriented private gardens (Zhang Garden, Yu Garden, Xu Garden, Dahua Garden); private residential gardens were represented by Aili Garden, (Aili Garden, Xi Garden) | The Buddhist cluster represented by Jing’an Temple (including Jing’an Temple, Jue Garden, and the Xin’s Family Garden). | By means of a well-developed transportation network, the area around Bubbling Well Road has become the “backyard garden” of the central district in the International Settlement. |

| State 4 | 1920–1940s | Peak of urbanization | Amusement parks and department stores | Jing’an Temple, Aili Garden, the Xi’s Family Garden, Jue Garden, Xu Garden | The emerging entertainment industry, represented by amusement parks and department stores, formed. Profit-oriented private gardens declined. The area around Bubbling Well Road completed its transformation from the entertainment industry to modern commerce. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Xu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Y. New Insights into the Layering Process of Urban Environment and Private Garden Transformations: A Case Study on the Bubbling Well Road Area in Early Modern Times, Shanghai. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13939. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813939

Chen Z, Xu Q, Zhou X, Yang Y. New Insights into the Layering Process of Urban Environment and Private Garden Transformations: A Case Study on the Bubbling Well Road Area in Early Modern Times, Shanghai. Sustainability. 2023; 15(18):13939. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813939

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zhehua, Qing Xu, Xiangpin Zhou, and Yanping Yang. 2023. "New Insights into the Layering Process of Urban Environment and Private Garden Transformations: A Case Study on the Bubbling Well Road Area in Early Modern Times, Shanghai" Sustainability 15, no. 18: 13939. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813939

APA StyleChen, Z., Xu, Q., Zhou, X., & Yang, Y. (2023). New Insights into the Layering Process of Urban Environment and Private Garden Transformations: A Case Study on the Bubbling Well Road Area in Early Modern Times, Shanghai. Sustainability, 15(18), 13939. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151813939