Abstract

Guided by the transactional model of stress and coping, we examined the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry among Israeli adults, with the interplay of risk appraisal, collective efficacy, age, and gender. Using an online survey with 402 participants, we found moderate levels of climate change worry. Higher climate change exposure, increased risk appraisal, and greater collective efficacy were associated with higher worry levels. Climate change risk appraisal mediated the relationship between climate change exposure and worry, whereas gender moderated the association between collective efficacy and worry. This study highlights the significant impact of climate change exposure on worry, emphasizing the roles of risk appraisal and collective efficacy, particularly among women, and underscores the need for tailored interventions to address emotional responses to climate change.

1. Introduction

Climate change is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the biggest health threat that humanity faces today [1]. Indeed, empirical evidence has shown that extreme weather events and natural disasters, such as floods and hurricanes, can have detrimental effects on mental well-being as well as adverse community health outcomes [2,3]. Moreover, increased CO2 emissions have been widely recognized as a major driver of anthropogenic climate change, contributing to a range of adverse impacts on the environment and human well-being [4]. The accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere leads to the greenhouse effect, trapping heat and causing global temperatures to rise, resulting in more frequent and intense heatwaves, altered precipitation patterns, and sea-level rises [5]. These changes disrupt ecosystems, impact biodiversity, and threaten agriculture and water resources [5,6].

In the current study, we focused on the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry among Israeli adults, with regard specifically to outdoor air pollution. A previous review conducted by Orru and colleagues [7] indicated that climate change increases air pollution. Specifically, climate change affects air quality as higher temperatures lead to an increase in allergens and harmful air pollutants. In addition, higher temperatures associated with climate change can also lead to an increase in O3, a harmful air pollutant.

The novelty of the current study lies in its focus on the Israeli population and the unique factors that shape climate change worry among this cohort. Although there have been studies in which climate change exposure and worry were examined in various countries, each region presents its own set of variables, cultural norms, and geographical susceptibilities that can affect the relationship between exposure and worry. In this regard, Van der Linden’s work [8] suggests that the degree to which individuals are worried about climate change can vary within countries due to social, cognitive, and cultural factors. To the best of our knowledge, climate change worry has not been assessed previously among Israeli adults, despite the fact that assessing the psychological impact of climate change is critical. It is widely recognized that human mental health is negatively affected by changing weather patterns [9]. Climate change worry is characterized by “verbal-linguistic thoughts primarily (rather than images) about the potential impacts of climate system changes. These thoughts may be persistent, repetitive, or challenging to manage” ([10], p. 4). It is important to note that the terms “climate change worry” and “climate anxiety” are often used interchangeably to describe the psychological distress caused by concerns about climate change. However, climate change worry generally refers to a general sense of concern or unease about climate change and its impacts, whereas climate anxiety refers to a more severe and persistent form of worry that can manifest as feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and overwhelm [11].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study Model

Two theoretical frameworks guided the present study. First, we used the transactional model of stress and coping [12], which postulates that potentially stressful events will trigger a primary appraisal process wherein people assess the degree of threat in relation to their well-being. On the basis of this primary appraisal, the secondary appraisal process provides a global assessment of people’s coping resources and ability to manage the threat/challenge. Thus, the following variables were suggested in the current study as variables that might contribute to the understanding of climate change worry: climate change exposure, climate change risk appraisal, and collective efficacy related to the environment.

Climate change exposure can intensify negative emotions about climate change by creating a more concrete and immediate sense of its impact [13,14]. In line with this notion, Ogunbode and colleagues [15] found, among a nationally representative British sample, that people who experienced flood damage to their property reported a significantly greater level of negative emotions than those who did not have flood-related property damage. Although in Israel climate change exposure seems to be mild, climate change worry is likely to become a graver concern both in Israel and globally in the years to come and therefore should be addressed. In the current study we aimed to shed light on this topic through exploring the direct and indirect associations (serial mediations) between climate change exposure, climate change risk appraisal (as it pertained specifically to air pollution), collective efficacy, and climate change worry.

Climate change risk appraisal refers to an individual’s monitoring of environmental events (e.g., air pollution, prolonged heat waves, desert dust, forest fires, droughts, floods, etc.) in terms of threat and harm appraisal [16]. In a recent study conducted in Israel, it was found that the higher the climate change exposure, the higher the climate change risk appraisal (i.e., as it pertained to air pollution) [17]. Likewise, Wang and colleagues [18] found that people from an Eastern cultural background had a medium-to-high level of climate change risk appraisal, suggesting that people from different cultural backgrounds may vary in their level of climate change risk appraisal. Thus, given that in Israel the attributable burden of premature deaths and disease from air pollution was approximately 5% of total deaths [19], we chose to focus on climate change risk appraisal as it pertained to air pollution (henceforth, climate change risk appraisal).

Collective efficacy (related to the environment) refers to people’s shared beliefs in their group’s ability to produce desired results regarding positive environmental outcomes through collective action [20]. This core belief will inevitably have implications for individuals’ ecological behavior, as it affects motivation and performance [21]. Several scholars have stated the importance of collective efficacy for predicting pro-environmental behavior (e.g., [15,22]). Furthermore, a prior investigation carried out in Italy, involving university students aged 18 to 26, revealed a positive correlation between individual and collective self-efficacy and climate anxiety [23]. This finding indicates that when self-efficacy (both individual and collective) increases, so does the level of anxiety, and conversely, a decrease in self-efficacy corresponds to a decrease in anxiety related to climate concerns [23]. Nevertheless, in a recent study [24] conducted in Switzerland, the association between collective efficacy and climate anxiety (as measured via climate worry) was not significant among adolescents aged 11–19, but self-efficacy was related to higher levels of climate anxiety. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated a direct link between greater exposure to climate change and higher levels of both self-efficacy and collective efficacy in Israeli adults [17].

In line with the social role theory [25], males and females are socialized in a different way and play different roles in our society. Previous researchers have revealed that women are more environmentally sensitive about general environmental issues than men are and are more likely to express concerns about the social and environmental impacts of their consumption [26,27]. Another social-demographic characteristic that may be relevant for environmental concerns is age. The results regarding age are inconclusive; Lewis and colleagues [28] found a positive relationship between age and environmental concerns, while other scholars have revealed that younger individuals are likely to be more sensitive and concerned about environmental issues than older individuals (e.g., [29]). In a recent study, Čater and Serafimova [27] found that age was positively associated with environmental concern and ecologically conscious consumer behavior, suggesting that the youngest age group (30 and below) was less environmentally concerned and less engaged in ecologically conscious consumer behavior than the other two age groups (31–50, and 51 and above).

Given the above, the purposes of this research were fourfold:

- (1)

- To explore the associations between climate change exposure, climate change risk appraisal, and collective efficacy and climate change worry.

- (2)

- To examine the role of climate change risk appraisal and collective efficacy as mediators (serial mediation) in the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry.

- (3)

- To assess the moderating role of age in the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry.

- (4)

- To assess the moderating role of gender in the association between collective efficacy and climate change worry.

We hypothesized that:

- (1)

- Climate change exposure and climate change risk appraisal would be positively associated with climate change worry, and collective efficacy would be negatively associated with climate change worry.

- (2)

- Climate change risk appraisal and collective efficacy would mediate the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry.

- (3)

- Age would moderate the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry, such that the association would be stronger for older participants.

- (4)

- Gender would moderate the association between collective efficacy and climate change worry, such that the association would be found for women but not for men.

2.2. Procedure

Our study involved an online survey of the Israeli population, which was conducted through a reliable Internet panel (iPanel). This panel comprises approximately 100,000 Israelis who conform to the demographic characteristics of the general population, as defined by the Israel Bureau of Statistics (http://www.ipanel.co.il/; accessed on 26 May 2022). In order to achieve a 95% confidence level and a 5% sampling error, a minimum sample size of 384 participants was determined. We also used G*Power 3 [30,31] to determine the necessary sample size for a multiple regression analysis involving up to 15 predictors, considering a moderate–low effect size (f2 = 0.10), a significance level of α = 0.05, and a power of 0.99. Our analysis showed that a sample size of N = 379 participants would suffice to meet these criteria. The number of potential participants (n = 5378) was determined on the basis of the company’s previous experience with response rates in order to arrive at the number of participants necessary for our study (n = 379).

Given the above, 5378 potential participants from this Internet panel were invited to participate in the study. The questionnaire was delivered to the respondents in the form of an Internet survey. To be eligible for participation in the study, individuals needed to meet two criteria: they had to be 18 years-of-age or above, and they had to possess fluent proficiency in the Hebrew language. Data collection occurred during the first two weeks of June 2022, when the COVID-19 pandemic was no longer a threat and regular activities were resumed. Four-hundred-and-two individuals (7.5%) filled out the questionnaires and participated in the study. The research received the approval of the first author’s university’s institutional review board (IRB; approval No. 052202) and all participants provided their consent by signing an electronic form before answering the questionnaires.

2.3. Measures

The assessment tools utilized in this study were self-report measures that have been validated.

Climate change worry was evaluated with the Climate Change Worry Scale (CCWS) [10]. This scale includes ten items intended to assess the intensity of negative and alarming thoughts that individuals experience about climate change (for instance, “I worry about how climate change may affect the people I care about”). Participants were instructed to rate the frequency of their climate change worry on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating never and 5 indicating always. A mean score was computed, with higher scores indicating greater levels of climate change worry (Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

Climate change exposure was evaluated using the Clayton and Karazsia [32] subscale of a climate change anxiety measure. This subscale comprises three statements, including: (1) “I have been directly affected by climate change”; (2) “I know someone who has been directly affected by climate change”; (3) “I have noticed a change in a place that is important to me due to climate change” ([32], p. 4). In the present study, participants were required to rate the frequency of each statement using a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating never and 5 indicating often. This assessment allowed the researchers to compute a mean score for the subscale, with higher scores on this scale representing increased levels of exposure to climate change (Cronbach’s α = 0.86).

Climate change risk appraisal was measured via Homburg and Stolberg’s [16] scale. This scale consists of two types of risk appraisal: threat and harm. Three items were used to measure threat (e.g., “I feel that my health is threatened by pollution in everyday life”), while an additional three items were used to measure harm (e.g., “My health has become worse as a result of the pollution in everyday life”). In this study, the participants were requested to express their level of agreement or disagreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). By calculating the mean score, higher levels of climate change risk appraisal were indicated by higher scores (Cronbach’s α = 0.73).

Collective efficacy was evaluated using Homburg and Stolberg’s scale [16]. The participants were presented with six statements and were asked to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree. The aim of the statements was to assess the participants’ belief in their ability, as a group, to solve environmental problems (e.g., “I am confident that together we can solve the problem of pollution”). A mean score was calculated, with higher scores indicating greater collective efficacy (Cronbach’s α = 0.93).

We also collected information about various sociodemographic variables, including gender, age, years of education, marital status, number of children, employment status, and religiosity. Participants were also asked to rate their overall health using a single question (“In general, how do you rate your health?”) with a scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 4 (excellent).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

The data collected in the study were analyzed using SPSS software version 28. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the participants’ demographic characteristics and research variables. The research variables did not deviate from normal distribution (Skewness = −1.05 to 0.81, SE = 0.12, Kurtosis = −0.59 to 1.81, SE = 0.24), and only two of the research variables had outliers, with up to nine (2.2%) different outliers for each variable. Pearson correlations were computed to examine the relationships between different research variables. The strength of the correlation was evaluated as follows: 0–0.30, weak; 0.31–0.50, moderate; 0.51- and higher, strong [33,34]. Pearson correlations and t-tests were employed to explore the associations between the study variables and background variables. For climate change worry, a multiple linear hierarchical regression was conducted, taking into account the study variables. Gender, age, and years of education were entered in the first step as control variables, and the study variables were entered in the following steps, according to the serial order of the study model (climate change exposure in the second step, climate change risk appraisal in the third, and collective efficacy in the fourth), in order to examine the contribution of each beyond the previous ones. The interactions that appear in the study model were entered in the fifth step. The moderated serial mediation model was examined with Hayes’ [35] PROCESS procedure, using a custom model, with 5000 bootstrap samples and 95% confidence intervals. Years of education was entered as a covariate, and gender was defined as 1-men, 0-women. The significant interaction was interpreted with the analysis of simple slopes.

3. Results

Participants

As mentioned, the study included 402 participants, about half of whom were women (51.5%), with a mean age of about 42 years (range 18–70), and an average education level of about 13.7 years (range 7–26). More than half were married (54.5%), and about two-thirds had children. About 77.3% were employed, and about 52% were secular. Most of the respondents (about 89%) perceived their health status as good or excellent (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics (n = 402).

Table 2 summarizes the means, SDs, ranges, and correlations for the study’s variables. As can be seen, the means for climate change worry and climate change risk appraisal were about moderate, whereas the mean for climate change exposure was rather low, and the mean for collective efficacy was rather high. Significant positive, moderate-to-high correlations were found among the study variables. Higher climate change exposure was associated with higher climate change worry. In addition, higher climate change exposure, higher climate change risk appraisal, higher collective efficacy, and higher climate change worry were all interrelated.

Table 2.

Means, SDs, ranges, Cronbach’s αs, and Pearson correlations for the study variables (n = 402).

A single weak association was found between the demographic variables and the study variables; namely, years of education was positively related to collective efficacy (r = 0.14, p = 0.007). Thus, the study’s hypotheses were examined while including gender and age as part of the equations and controlling for years of education.

Table 3 shows a multiple linear regression for climate change worry, indicating a significant model with 57% of the variance in climate change worry being explained. Each component of the model made a significant contribution to climate change worry over and above the previous components, and beyond gender, age, and years of education. Higher climate change exposure, higher climate change risk appraisal, and greater collective efficacy were found to be related to higher climate change worry.

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression for climate change worry (N = 402).

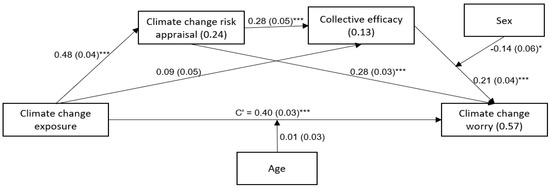

The moderated serial mediation for climate change exposure, climate change appraisal, collective efficacy, and climate change worry is shown in Figure 1. Results in the figure show that all direct associations (except for the association between climate change exposure and collective efficacy) were significant (p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Moderated serial mediation for climate change exposure, climate change risk appraisal, collective efficacy, and climate change worry. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. Note. Values on arrows: B(SE), values within rectangles: R2, C′ = direct effect.

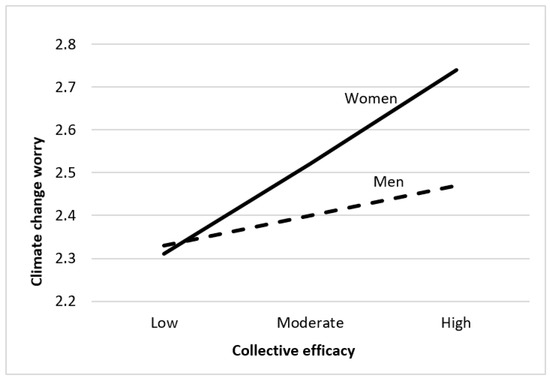

Further, the moderating effect of gender on the association between collective efficacy and climate change worry was significant (B = −0.14, SE = 0.06, p = 0.0129, 95%CI = −0.26, −0.03). The moderating effect of age on the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry was non-significant (B = 0.01, SE = 0.03, p = 0.0995, 95%CI = −0.06, 0.06). An interpretation of the significant interaction of gender (Figure 2) shows that the effect was significant for women (B = 0.21, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95%CI = 0.12, 0.30) and non-significant for men (B = 0.07, SE = 0.04, p = 0.090, 95%CI = −0.01, 0.15). The indirect effect of climate change exposure—climate change risk appraisal--climate change worry was significant (B = 0.14, SE = 0.02, 95%CI = 0.09, 0.18), yet the indirect effect of climate change exposure—collective efficacy—climate change worry was significant only for women (B = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95%CI = 0.01, 0.04) and not for men (B = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95%CI = −0.01, 0.02). Likewise, the indirect effect of the whole model’s serial mediation was significant only for women (B = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95%CI = 0.01, 0.05) and not for men (B = 0.01, SE = 0.01, 95%CI = −0.01, 0.02). Finally, the total index of moderated mediation was significant for gender (index = −0.02, SE = 0.01, 95%CI = −0.04, −0.01).

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of gender on the relationship between collective efficacy and climate change worry.

4. Discussion

In this research, we examined the correlation between climate change exposure and climate change worry in Israeli adults, analyzing the interplay of risk appraisal, collective efficacy, age, and gender.

Our results show that the levels of climate change worry were moderate, relative to the scale range. In contrast to this finding, a recent literature review [36] focusing on climate change and human health in the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East emphasized the profound impact of various climate-related factors on the mental well-being of populations in the region. This broader assessment underscores the fact that Israel’s neighboring countries, such as Jordan, Syria, Egypt, and Lebanon, face a heightened prevalence of mental health issues due to the direct and indirect consequences of abnormal and extreme climate fluctuations, including extreme heat, water shortages, air pollution, droughts, earthquakes, and forest fires [37]. Several explanations may clarify the finding of moderate levels of climate change worry found in the current study. First, the study was conducted during the first two weeks of June, a period when Israel experiences comfortable weather with temperatures typically ranging between 25 to 30 degrees Celsius (77 to 86 degrees Fahrenheit). This timeframe marks the transition from spring to early summer, offering mild to moderately warm conditions conducive to outdoor activities and daily routines. Conducting the study during the height of summer or winter might have yielded different results, considering the heightened likelihood of people expressing climate change-related worries during hotter or colder months or specific days [38]. Second, it seems that the issue of climate change has not yet been fully assimilated in Israel. On the one hand, there is a certain level of public discourse with regard to this topic [39]; on the other hand, there is no regulated legislation which would likely affect beliefs, awareness, and related knowledge about climate change, possibly resulting in the moderate level of climate change worry that was found in this study. In line with this notion, a recent study revealed that higher rates of information exposure (via the media) about the possible consequences of climate change had a significant association with higher climate anxiety [40]. Third, individuals who live in Israel may be more concerned with other significant current threats, such as the security situation [41]; in other words, issues that do not constitute an immediate threat to the Israeli public may not be as worrisome as those that do. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that although most of the national and international attention is focused on the direct causes of climate change, negative emotional reactions resulting from climate change should also be addressed.

Our first hypothesis was partially confirmed, as higher climate change exposure was associated with higher climate change worry. Indeed, individuals’ concerns or worry regarding climate change may escalate when they directly encounter extreme weather events that they attribute to climate change [42]. However, higher climate change risk appraisal and higher collective efficacy were associated with higher climate change worry. The positive association that we found between collective efficacy and climate change worry was unexpected. According to Lazarus and Folkman’s [12] transactional model of stress and coping, collective efficacy may serve as a coping resource that can function as a buffer against emotional responses in the face of a threatening or stressful situation [43]. Yet it seems that in the current study, collective efficacy was not understood to be something that could enable participants to respond adaptively to climate change threats (i.e., by attenuating their emotional responses). Another plausible interpretation, drawing from existential theory, posits that individuals with greater collective efficacy exhibit the capacity to undertake responsibility for global environmental issues, which, in turn, may be associated with increased levels of worry [44].

Contrary to our second hypothesis, collective efficacy did not mediate the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry. This finding contrasts with findings from a recent study conducted among the general public in Israel which found that collective efficacy mediated the association between climate change exposure and behavioral reactions [17]. In the case of emotional reactions as an outcome, as measured in the current study, we did not find a mediation effect of collective efficacy. A possible explanation may be related to the construct of collective efficacy. Bandura’s perspective [45] suggests that collective efficacy is a concept that pertains to the group as a whole, and it is made up of the perceptions of individual members. Therefore, it is important to ensure that all members of the group have similar perceptions about their team or group. In line with this notion, it might be that collective efficacy became a redundant factor in the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry. However, in line with our third hypothesis, we found that climate change risk appraisal mediated the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry. In accordance with the cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion [46], the evaluation of climate change risk appraisal can be interpreted as a psychological indication of how important a particular stimulus is to an individual’s values, goals, and concerns. This theory suggests that risk appraisal, as a psychological measure, plays a role in the connection between a stimulus that is relevant to a person’s values and emotional reactions. The significance of climate change risk appraisal as a mediator supports findings from a previous study indicating that relative risk perception is the starting point of physical and emotional adaptation to climate change [47].

Our third hypothesis was not supported by the findings, as the moderating effect of age on the association between climate change exposure and climate change worry was non-significant. Although studies have overall suggested an increase in people’s psychological adaptive capacity with age (e.g., [48]), in this study we took into consideration intricate relationships between certain specific factors in a particular context. The global literature indicates that both children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable to climate-related mental health outcomes [41]. Climate change is attributed to the actions of past and present generations. However, its consequences will manifest in the future, affecting different age groups differently (e.g., elderly individuals may have less effective coping mechanisms against climate change). Currently, people of all ages are susceptible to the effects of climate change, with no differences having been found between ages [49]. Indeed, age did not play a role in the relationship between climate change exposure and climate change worry in the current study.

Our fourth hypothesis was confirmed, as gender moderated the association between collective efficacy and climate change worry, such that the association was significant for women and not for men. An explanation of our results may be related to the concept of “social role”, which refers to different gender-based hierarchical standards within societies [50]. Diverse social roles and gender-related social norms engender distinct social encounters and expectations as individuals are socialized to fulfill these varied roles [51]. As a result, women’s increased environmental engagement, elevated collective efficacy, and heightened climate change worry may stem from traditional gender roles and socialization patterns. Moreover, in general, women tend to assess the world as more hazardous and perceive higher levels of environmental risk, leading to a greater likelihood of expressing worries about climate change [52].

The current research has a few limitations. First, given the study’s cross-sectional design, we were unable to establish cause-and-effect relationships among the variables examined. For a more definitive understanding of the causal links between climate change exposure, climate change appraisal, collective efficacy, and climate change worry, longitudinal studies that track these variables at multiple time points would offer greater clarity. Second, given the use of a convenience sample, it is not possible to extend the findings to Israel’s wider population, nor can we provide a comprehensive picture of the views of all of the people in the country. Additionally, the data represent a specific timeframe (June 2022), and given that climate change is a dynamic phenomenon, the rates and patterns observed may not necessarily persist over time. Going forward, researchers should enhance the study’s impact by employing wider samples and longitudinal designs, offering a broader perspective on climate change worry and its associations. Investigating worry across various seasons and climate conditions would provide nuanced insights into the dynamics of this phenomenon, enabling more effective policy and intervention strategies. Third, there is a chance that climate change may not be the root cause of people’s worry, but rather a symptom of compromised mental well-being [40]. Namely, increased worry can be a sign of various mental health issues [53]. To overcome this limitation, researchers should try to differentiate between climate-related worries and dispositional pathological worrying by taking into account the degree to which participants typically worry about other relevant topics, such as the world economy or “personal issues” (e.g., [54]). By doing so, researchers would be able to establish whether climate change worry is a specific manifestation or a broader pattern of pathological worry. Fourth, it is possible that the study’s results were influenced by social desirability bias, which refers to participants’ inclination to provide answers that they believe will present a positive image of themselves. To mitigate this limitation, researchers could employ techniques to minimize social desirability bias, such as utilizing indirect questioning. Additionally, we did not explore the population’s “awareness level” regarding climate change and its effects. Investigating this aspect could be important, as insights could emerge regarding public understanding and consciousness [55]. Thus, in future studies we would recommend including this variable to enrich the understanding of climate change perceptions. In addition, in light of the gender differences found in this study, we would recommend that researchers examine how cultural norms and gender roles intersect with climate change perceptions in various countries. Comparing societies with differing levels of gender equality would offer insights into how these factors impact the observed gender disparities in climate change worry. Lastly, we did not extensively compare men’s vs. women’s background characteristics. This limitation highlights potential unexplored variables that might have impacted our findings. In the future, researchers could delve into these aspects to enrich the understanding of gender as it relates to climate change perceptions.

Despite these limitations, the present study has important theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, our findings broaden the existing knowledge regarding factors that influence climate change worry, indicating that climate change exposure, climate change risk appraisal, and collective efficacy are significant determinants of climate change worry. Our findings can serve as a theoretical basis for the investigation of other determinants of climate change worry among the lay public. In addition, our findings indicate that the transactional model of stress and coping [12] can serve as a theoretical framework for understanding environmental threats. This model might be particularly relevant for emotions regarding the environment, as messages related to climate change often rely on using existential threats [56]. Based on the study’s findings, we would recommend specifically tailoring policies. Namely, to address the moderate levels of climate change worry identified, targeted interventions should be devised to enhance public awareness and education about climate change’s local implications. These efforts could include media campaigns, workshops, and community discussions that engage citizens in understanding the interconnectedness between climate change, air pollution, and mental well-being. Given the unexpected positive association between collective efficacy and climate change worry, policies could promote collective action through community-based initiatives that empower individuals to contribute to environmental resilience. Furthermore, recognizing the gender-specific impact on climate change worry, policy interventions should take into account women’s distinct concerns and encourage their active participation in climate-related decision-making processes.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant impact of climate change exposure on worry, emphasizing the roles of risk appraisal and collective efficacy, particularly among women, and underscores the need for tailored interventions to address emotional responses to climate change. The complex interplay of collective efficacy, climate change exposure, and risk appraisal emerges as a determinant of climate change worry, and the unexpected findings suggest the need for further exploration. The absence of a mediating effect by collective efficacy on climate change worry contrasts with previous research and is possibly rooted in the multifaceted nature of this construct. However, this study substantiates the mediating role of climate change risk appraisal, highlighting the importance of understanding perceived risks as they relate to personal values and concerns. Although age does not seem to moderate the association between collective-efficacy and climate change worry, our research confirms a gender-based effect, where collective efficacy plays a more significant role in shaping women’s (rather than men’s) climate change worry. The results offer valuable theoretical implications, contributing to the discourse on climate change worry determinants and suggesting that the transactional model of stress and coping is a relevant framework to understanding climate change worry. Regarding practical implications, the study calls for tailored interventions that acknowledge and address emotional responses related to climate change. On the basis of our results, we recommend interventions that promote emotional support and guidance, especially for women.

Author Contributions

Both authors made substantial contributions to the reported work, encompassing conception, study design, execution, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. They actively participated in drafting, revising, and critically reviewing the article and granted final approval for its publication. The authors have reached a consensus on the journal to which the article has been submitted and have assumed responsibility for all aspects of the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

External funding was not obtained for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethic Committee Name: Bar Ilan University IRB Committee, Approval Code: 052202, Approval Date: May 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Participants were informed that proceeding to the questionnaire would indicate their consent to participate, as stated on the survey’s introductory page.

Data Availability Statement

The authors can provide the data supporting the study’s findings upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shyam Biswal at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine for his valuable suggestions on this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Health and Climate Change: Country Profile 2022: Israel; (No. WHO/HEP/ECH/CCH/22.01.06); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cianconi, P.; Betrò, S.; Janiri, L. The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health: A Systematic Descriptive Review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganstein, J.C.; Ursano, R.J. Ecological Disasters and Mental Health: Causes, Consequences, and Interventions. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Saydaliev, H.B.; Iqbal, W.; Irfan, M. Measuring the impact of economic policies on co2 emissions: Ways to achieve green economic recovery in the post-COVID-19 era. Clim. Chang. Econ. 2022, 13, 2240010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, A.A.; Jiang, Y.; Akram, W.; Adeel, S.; Irfan, M.; Jan, I. Addressing the effect of climate change in the framework of financial and technological development on cereal production in Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orru, H.; Ebi, K.L.; Forsberg, B. The Interplay of Climate Change and Air Pollution on Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, S. Determinants and measurement of climate change risk perception, worry, and concern. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti, M.; Santarelli, G.; Faggi, V.; Ciabini, L.; Castellini, G.; Galassi, F.; Ricca, V. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the climate change worry scale. J. Clim. Chang. Health 2022, 6, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.E. Psychometric Properties of the Climate Change Worry Scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Doran, R.; Hanss, D.; Ojala, M.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Broek, K.L.v.D.; Bhullar, N.; Aquino, S.D.; Marot, T.; Schermer, J.A.; et al. Climate anxiety, wellbeing and pro-environmental action: Correlates of negative emotional responses to climate change in 32 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 84, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist, M.; Nilsson, A.; Schultz, P.W. Experiencing a Severe Weather Event Increases Concern About Climate Change. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konisky, D.M.; Hughes, L.; Kaylor, C.H. Extreme weather events and climate change concern. Clim. Chang. 2015, 134, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Böhm, G.; Capstick, S.B.; Demski, C.; Spence, A.; Tausch, N. The resilience paradox: Flooding experience, coping and climate change mitigation intentions. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, A.; Stolberg, A. Explaining pro-environmental behavior with a cognitive theory of stress. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinan-Altman, S.; Hamama-Raz, Y. Factors associated with pro-environmental behaviors in Israel: A comparison between participants with and without a chronic disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Geng, L.; Rodríguez-Casallas, J.D. How and when higher climate change risk perception promotes less climate change inaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, N.; Agai-Shai, K.; Erel, Y.; Schaffer, G.; Greenfeld, A. Economic Cost of the Health Burden Caused by Selected Pollutants in the Haifa Bay Area; Final Report; Ministry of Environmental Protection: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2020.

- Bandura, A. Exercise of Human Agency Through Collective Efficacy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 9, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado, E.; Macias-Zambrano, L.H.; Carpio, A.J.; Tabernero, C. The moderating effect of collective efficacy on the relationship between environmental values and ecological behaviors. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 4175–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, D.A.; Begotti, T. Media Exposure to Climate Change, Anxiety, and Efficacy Beliefs in a Sample of Italian University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrasin, O.; Henry, J.L.A.; Masserey, C.; Graff, F. The Relationships between Adolescents’ Climate Anxiety, Efficacy Beliefs, Group Dynamics, and Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intentions after a Group-Based Environmental Education Intervention. Youth 2022, 2, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, J. Sex differences in social behavior: Are social role and evolutionary explanations compatible? Am. Psychol. 1996, 51, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochado, A.; Teiga, N.; Oliveira-Brochado, F. The ecological conscious consumer behaviour: Are the activists different? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čater, B.; Serafimova, J. The influence of socio-demographic characteristics on environmental concern and ecologically conscious consumer behaviour among Macedonian consumers. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2019, 21, 213–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.B.; Palm, R.; Feng, B. Cross-national variation in determinants of climate change concern. Environ. Politi 2019, 28, 793–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, N. Absolute income, relative income and environmental concern: Evidence from different regions in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhard, W.; Lenhard, A. Calculation of Effect Sizes; Psychometrica: Dettelbach, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://www.psychometrica.de/effect_size.html (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Neira, M.; Erguler, K.; Ahmady-Birgani, H.; AL-Hmoud, N.D.; Fears, R.; Gogos, C.; Hobbhahn, N.; Koliou, M.; Kostrikis, L.G.; Lelieveld, J.; et al. Climate change and human health in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East: Literature review, research priorities and policy suggestions. Environ. Res. 2022, 216, 114537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnout, B.A. An epidemiological study of mental health problems related to climate change: A procedural framework for mental health system workers. Work 2023, 75, 813–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlon, J.R.; Wang, X.; Mildenberger, M.; Bergquist, P.; Swain, S.; Hayhoe, K.; Howe, P.D.; Maibach, E.; Leiserowitz, A. Hot dry days increase perceived experience with global warming. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 68, 102247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitan, A. Promoting Renewable Energy to Cope with Climate Change—Policy Discourse in Israel. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Pallesen, S.; Böhm, G.; Doran, R.; Bhullar, N.; Aquino, S.; Marot, T.; Schermer, J.A.; Wlodarczyk, A.; Lu, S.; et al. Negative emotions about climate change are related to insomnia symptoms and mental health: Cross-sectional evidence from 25 countries. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodman, D. Israel’s post-1948 security experience. In Routledge Handbook on Israeli Security; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, J.; Cunsolo, A.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Wright, C.J.; Harper, S.L. Indigenous mental health in a changing climate: A systematic scoping review of the global literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 053001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Zobeidi, T.; Moghadam, M.T.; Komendantova, N.; Löhr, K.; Sieber, S. Cognitive theory of stress and farmers’ responses to the COVID 19 shock; a model to assess coping behaviors with stress among farmers in southern Iran. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 64, 102513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. L’efficacité organisationnelle collective [Collective organizational efficacy]. In Auto-Efficacité: Le Sentiment D’efficacité Personnelle; Bandura, A., Ed.; De Boeck: Brussels, Belgium, 2003; pp. 694–715. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, S.; Gianoli, A.; Van Eerd, M. The roles of community resilience and risk appraisal in climate change adaptation: The experience of the Kannagi Nagar resettlement in Chennai. Environ. Urban. 2021, 33, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinan-Altman, S.; Levkovich, I.; Dror, M. Are Daily Stressors Associated with Happiness in Old Age? The Contribution of Coping Resources. Int. J. Gerontol. 2020, 14, 293–297. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L.; Roy, S. The Role of Ageism in Climate Change Worries and Willingness to Act. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2023, 42, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizotte, M.-K. The gender gap in public opinion: Exploring social role theory as an explanation. In The Political Psychology of Women in U.S. Politics; Bos, A.L., Schneider, M.C., Eds.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, S.; Telešienė, A.; Pazokinejad, Z. Socio-Cultural Determinants and the Moderating Effect of Gender in Adopting Sustainable Consumption Behavior among University Students in Iran and Japan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Egea, J.M.; García-De-Frutos, N.; Antolín-López, R. Why Do Some People Do “More” to Mitigate Climate Change than Others? Exploring Heterogeneity in Psycho-Social Associations. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, C.R.; Mathews, A. A cognitive model of pathological worry. Behav. Res. Ther. 2012, 50, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verplanken, B.; Marks, E.; Dobromir, A.I. On the nature of eco-anxiety: How constructive or unconstructive is habitual worry about global warming? J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiardi, D.; Morana, C. Climate change awareness: Empirical evidence for the European Union. Energy Econ. 2021, 96, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsen, T.; Palm, R.; Kingsland, J.T. The Impact of Message Source on the Effectiveness of Communications About Climate Change. Sci. Commun. 2019, 41, 464–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).