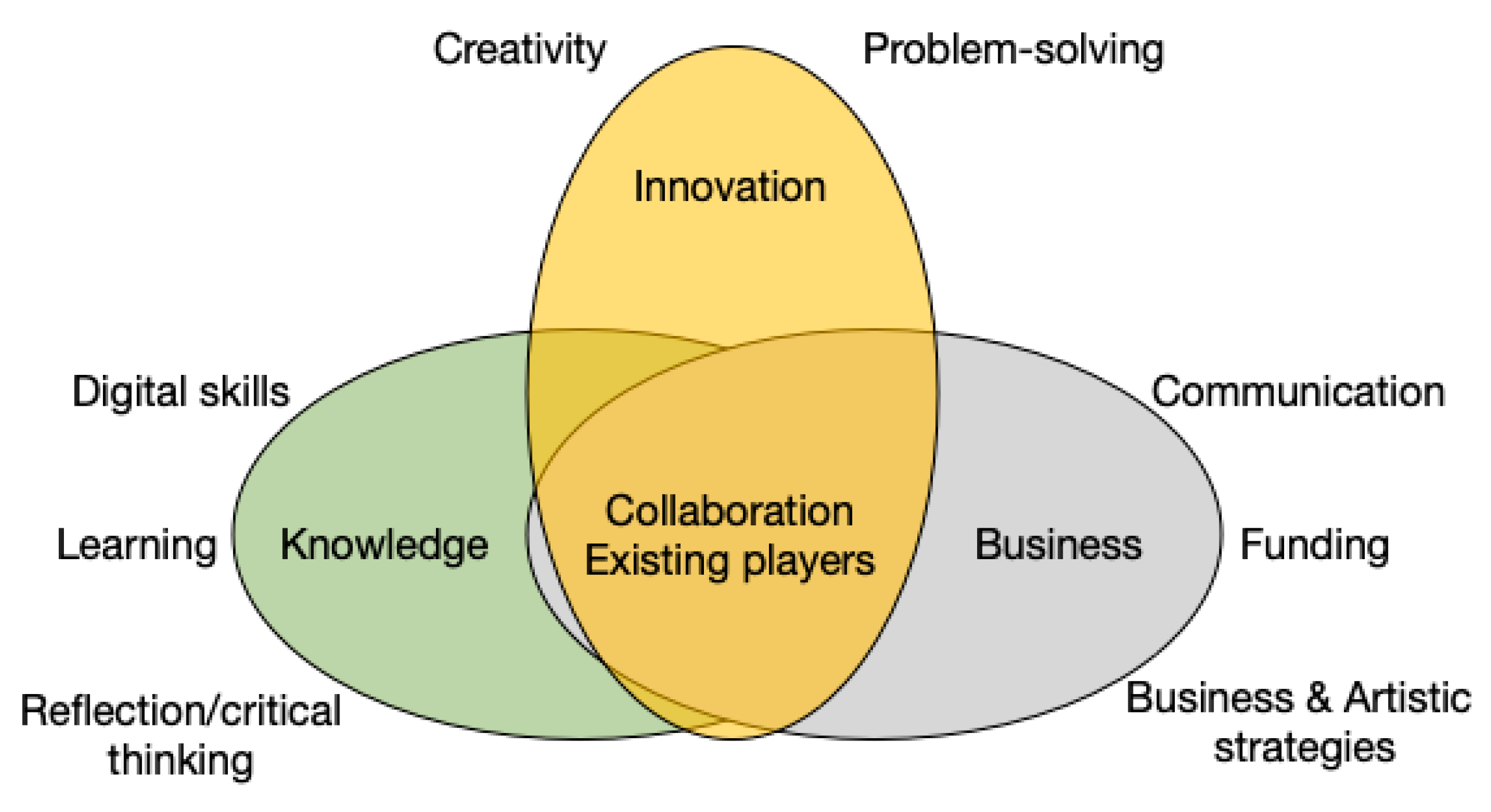

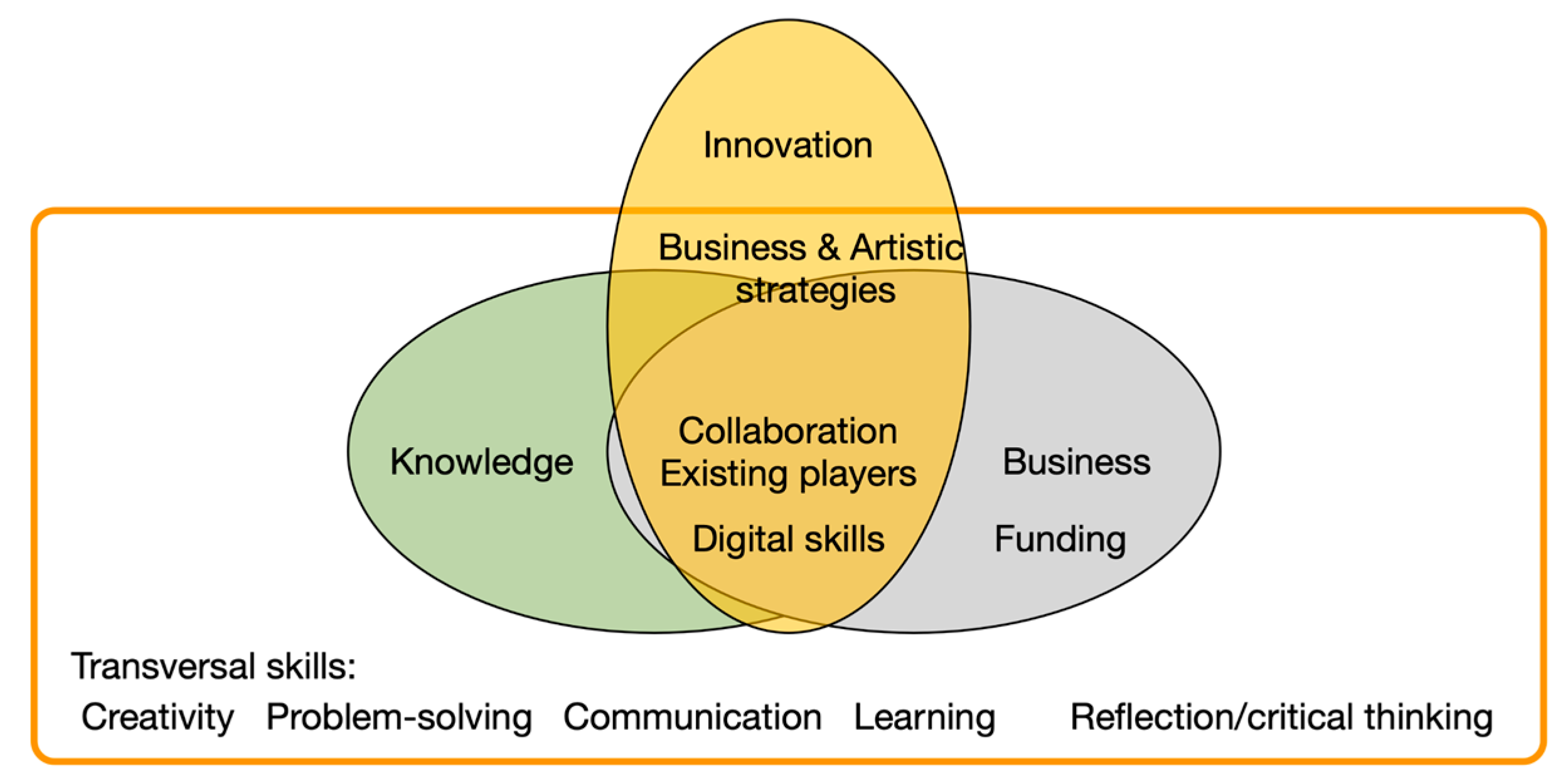

The analysis follows the structure of the created framework: (A) knowledge creation, including (a) digital skills, (b) learning, and (c) reflection; (B) innovation, following (a) creativity and (b) problem-solving; and (C) business, including (a) communication, (b) funding, and (c) business and artistic strategies.

We will also reflect on where to add, for instance, the themes that emerged from the data, such as the use of social media. We will discuss the three datasets to determine if the combined model works and to see if the co-design workshop participants—the creatives from the field—had the same view as the representatives in the semi-structured interviews. We call the semi-structured interview persons interviewees or experts on CE and the participants of the co-design workshops participants or creatives.

5.1. Analysis Using the Combined Model

(A) Knowledge creation, including (a) digital skills, (b) learning, and (c) reflection.

The experts on the CE understood digital skills as creative tools, and marketing and business skills. SP5(8) mentioned that most artists know the tools and master the skills for their creative processes but lack marketing, strategy, and business skills, and are reluctant to learn them. “Most creative companies are very, very strongly connected to any visual material that they create. And most of the computer skills that people are mostly focusing on, […] using various Adobe programs to alter the photos or a little bit of maybe graphic design, as well, to do. But it’s mostly for like creating the brand image and marketing materials. […] The programming part is used for designing processes as well. I feel that maybe other companies don’t use the software as much for the creation process of their product or service. But advertising their product is the main focus where the programmes come in. […] Then, they go back to the pen and paper, I guess because it’s quicker and easier. For the time being, before they’re growing.”—SP5(8).

The same view comes from the creatives (participants). All participants knew many digital tools and used the tools in creative processes at a professional level. In addition, they were constantly upscaling, improving, and learning more about their artistic and creative practices. (See

Appendix A,

Table A1 and

Table A2).

During the reflection discussion, the participants mentioned the following:

“All the art stuff”—WS1(1); “practical, drawing, painting….”—WS2(2); “Skills of creative thinking, creative things […] Resilience” —WS1(3); “creative development, Good listener, nurturing person, open-minded, patient, resilient, talker, communicator”.

WS3(4)

The skills that were lacking were in marketing and communication, as well as in building, maintaining, and changing artistic and business strategies (see

Appendix A,

Table A2 and

Table A3).

“Like to have marketing, AD, […] Communication: […] Time management, it stops me most, extra hours, and, i.e., management skills, not good at time management, […] I am not using it well, not learning as much as I want,—Prioritising is part of it […] Would be nice, someone else selling, so much better passionate about selling thing, but they keep saying that one should do Itself”.

WS1(5)

“I need marketing skills, project management—time management—someone taking off my social media count, write something about what this artist is about”.

WS2(8)

“Marketing—we all do have the need” […] “What post, when I feel, I post, when not feel to, I do not, so no strategy”.

WS1(13)

The experts on the CE mentioned that the learning methods provided for creatives include two-year programs, workshops, and mentoring, and that these methods aim for strategy training:

“two-year programme, where the company gets a consultant. And throughout this period, they can take part in different training courses. We have 45 mentors who are experts in their specific field […] to understand marketing and kind of the technical side behind that. […] like using Google Analytics and the coding part of it and how you can enhance your appearance online by actually implementing some behind-the-scenes programming. […] Photoshop and Illustrator, and those skills to edit photos are always something they’re keen on learning more about.” […] Their stock and management of their materials also is something that most of them are doing on paper, and you know, it’s loose in their head; I guess they could use software for that, that would definitely make it more efficient for them”.

SP5(9)

“We should focus, we should have this strategy, we should move forward with this one and leave others behind, and then these kinds of strategies are really difficult to integrate into the companies because of the lack of resources”.

SP1(10)

However, it is worth mentioning the training costs. The participants mentioned learning in various forms, such as self-directed learning, learning from peers, and learning by doing or imitating. Learning occurs everywhere, at home, online, in school, in workshops, and while practising the profession (see

Appendix A,

Table A3 and

Table A4).

“school”—WS2(7); “Study groups, courses, […] Workshops”—WS1(8); “Manage full-time smaller workshops, time managing better, own time, not dependent on the other private workshop.”—WS1(9); “Outdoors as well, breakfast brunch, informal setting, VR—learning through VR”.

WS3(10)

“Alone learning mostly (the diver), an artist sees things tuned […] self-directed learning […] Through experimentation, analysing others’ work, getting to the end result, […] experiments, experiences […] learning from other artists, from experience, like by doing—learn again, start over again, backup files, from mistakes I learn to do it right […] Investigate it about, trying to build it and then try and then again, like a process, you know that you need to do this thing, research approach to investigate […] Meeting new people, listening to their experiences, they can tell me, I do not have to make the same mistake”.

WS1(11)

The ability to acknowledge one’s weak and strong points and to understand how, where, and in which way one learns the best shows that the participants reflected considerably on their practices. All participants mentioned learning from mistakes when reflecting on their practices or analysing others. An interesting point is the need for curiosity (see

Appendix A,

Table A3). It is well known to support learning, but coming intuitively as a skill that the participants had, or wanted to enhance, indicated well-practised self-reflection [

46]. The learning skills were well-mastered (transversal skills), and the participants knew their knowledge gaps and needs in the creative economy. However, the top-down accelerators, training centres, and incubators might have to respect the voices from the field more, since the above quotations demonstrate a mismatch between learning habits and the support provided for learning.

The co-design workshop participants felt that marketing, communication, and strategy creation should be something to delegate. Some had already tried, but it had not worked. The discourse in the literature, which some interviewees also raised, is that funding and training are directed towards teaching managerial and entrepreneurial skills to creative economy people. Based on the current study, training and funding should be directed towards supporting professional growth and hiring specialists for marketing and strategy building.

(B) Innovation—(a) creativity and (b) problem solving.

The interviewees did not specifically talk about creativity; it was taken more or less for granted, nor was problem solving discussed intensely. However, the participants mentioned creative thinking, intuition, curiosity, and creative writing (

Appendix A,

Table A2 and

Table A4).

“Skills of creative thinking, creative things in our brain see some things other people do not see and small things in everyday life, those small things are beautiful to mean a lot” —WS1(3); “creative development”—WS3(4). Various examples of making mistakes, trial and error, systematising thinking, stubbornly pushing forward, being lazy, and recognising what others do not (e.g., WS1(11), above) were demonstrated. Thus, they discussed the creative and problem-solving processes. Both of these processes included reflection in a myriad of forms.

Adopting the core 21st-century digital skills—technical knowledge, information processing, communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills [

16]—is well-achieved and acknowledged by the interviewees and the participants. However, there is a visible gap in the interviewees’ understanding of the wide variety of creative people’s forms of learning. We gathered from the above (A) and (B) framework directions that the creatives preferred self-directed learning or learning with peers and were also highly reflective, mastering critical and creative thinking [

34].

(C) Business—Ecosystems—(a) communication and collaboration, (b) funding, and (c) business and artistic strategies.

From the experts on the CE, it is worth mentioning the statements emphasising the differences between the formal learning context and the real-life creating of a business:

“It’s totally two different worlds. In the university, they are like; we have this boutique university. This is also like a good thing but a bad thing as well. Because they have a lot of teachers per one or two students, so they’re well guided, they’re protected […] they have really good mentors, and they are taking them as their children. So, you know that creative people are a little bit maybe sensitive, but on the outside, they face the real world. […] and they don’t push you to work together with the teams […] This is my personal opinion, why the companies are small and don’t have competitive advantages, because of their smallness, they don’t have resources, they don’t have resources for selling. […] Yes, we are not cooperating a lot. And we are afraid or don’t trust each other”.

SP1(1)

Being small and not having resources was also expressed by SP5(2). “A lot of businesses in the creative industry, they’re really […] the money Is […] it’s very limited. So, every expense is counted for […] It can sometimes be two people” working in a team, staying small in size, and having limited resources.”

Estonia, as a tiny country in size and population, “lacks niche markets”—SP1(3); “And you are not an expert on one field, you are a little bit expert on every field.”—SP2(4). Being unprepared for the CE may contribute to the reluctance for collaboration. Two other reasons that were also provided were the unsuccessful funding for export, and the reduced willingness for future collaboration and applying for funding:

“Companies who applied for money to try to develop the export field failed, and the Agency (name changed) asked for their money back, and then they went bankrupt. I think companies are afraid to take this path because of the examples, and they see how difficult it is to be successful outside of Estonia”.

SP1(6)

Large companies are dominating the field and attempting to merge the smaller ones into them, which does not accord with the creative people’s values of freedom, respect, acceptance, and reliability (see

Appendix A,

Table A6).

“It’s, unfortunately, the big software companies still getting along with each other and as architects and other players are using a different tool if they are not from the one source company”.

SP2(7)

The peculiarities of Estonia explained some of the problems that the co-design workshop participants mentioned in their need to improve communication, marketing, and artistic and business strategies (e.g.,

Appendix A,

Table A3). Nevertheless, it is not in a form that was suggested in the literature, and was partially suggested by the experts on the CE as courses and two-year programmes. Instead, there should be shared, self-regulated learning in different forms, elevated from the bottom-up. Collaboration, on the other hand, was seen to work more or less well:

“Interdisciplinary it is done, but it is just invisible; it used to be less than now. I wish there could be more; everything can be collaborative with Artists, stage design, costumes, etc., out of the field are programmers. […] How do you collaborate, clients—communication does not work any other way than having mutual respect; they have to understand each other, and you need common ground; otherwise, it is not going to work out if there is a foundation, you can throw the ball back and forth, and that provides good outcomes and collaboration to the end. Friendship can even be built through collaboration, face-to-face to meetings”.

WS2(17)

In addition, the participants discussed the diverse needs for collaboration. The participants mentioned that respect, shared values, and expertise are essential for collaboration and ecosystems. It is worth mentioning that these values support diversity and the sharing of resources; we could say that these imply sustainable values. “Universal income, transparent teams would help with the gender gap, teams with a different team (diverse) backgrounds such as education; business is better with diverse—natural successful diversity, psychological help for companies. […] Common values, or base, reliability, you can rely on these people, reduce costs between these people, a crucial point for the ecosystem to be successful and stable” […] “One recommends another—do me a favour, e.g., I do not have to do the marketing.”—WS3(20).

The co-design workshop participants had an extensive list of professionals with whom collaboration could occur, such as dentists, assistants, psychologists, people with vans, salespeople, copywriters, barristers, IT specialists, web page designers, and metal workers, as well as people in the transport, carpentry, and printing industries:

“Investor s– money people, that is where to collaborate with other sectors. Mathematicians, builders or art festival artists together program the theme where others can be combined. I wish there would be more of it; it is not done as much as it could be” […] sales persons, assistants […] Transport people with vans, salespeople, copywriters, someone who knows the law, someone dealing with the webpages and all that IT”.

WS1(19)

The participants also pondered the need for ecosystems. The pondering on ecosystems directed the discussion toward social media and the difficulties of understanding and using the algorithms so that they could be exploited effectively for artistic purposes, inspiration, and gaining followers:

“If you post once or twice a year, no one knows.” […] “Really hard to stand out and gain followers” […] “Instagram and FB page, Tumblr home page, I do not have a strategy either, it does not work, most of the sales are from Instagram”.

WS1(14)

“I do not like that social media does the filtering for us; I should be doing the filtering […] I do not like TikTok; too many ads and I am too sceptical […] Instagram is about videos and reels; you cannot find anything you want to see, and people pay for their posts to show, and the ones you used to follow disappear, so it … Tik Tok, problematic, fast action, fast earning”.

WS1(15)

The participants would like to have modifiable algorithms for the potential ecosystem platform; for instance, filtering can be carried out by oneself, choosing one’s channels and creating algorithms on one’s own.

“I do not like that social media does the filtering for us […] Algorithms—create your own. Switch between algorithms. What I do not like about Instagram is that it only shows you the images of the people you visit frequently, so it does not show those who post rarely but are very good posts”.

WS1(21)

In addition, the participants required guidance on NFT and GDPR use. “GDPR, IT talking, I would ask my IT friends”—WS1(16). Support was also requested for “green BFT” or how to detect greenwash.

The ecosystem should be built on shared values, universal income, transparency, diversity, and reliability for sharing experiences and trading (WS3(20)). The setting up of an ecosystem needs scaffolds for long-term funding, novel algorithms respecting the values of the ecosystem members, and heterogenous forms of learning and collaborating.

The values that the participants mentioned differ from the current aims for growth; the values presented by the workshop participants come closer to degrowth values and are related to sustainability, which the participants wished for [

12,

15,

26]. The values mentioned were the following (

Appendix A,

Table A6): simplicity, connecting with nature, a sense of belonging, open-mindedness, safety, diversity, and acceptance. Ecosystems should be grounded on mutual benefits, reliability, cost reduction, flexibility, creativity, and freedom.

5.2. Answering Research Questions

RQ1: What kind of needs, skills, and learning habits exist among creatives?

We can state that the skills of the creative economy professionals were multiform in their area of expertise—the “artistic stuff” (WS1(1)). The most mentioned tools and skills have been listed in

Appendix A,

Table A1 and

Table A2, and include the following: art/craft tools and techniques (15 comments), digital art tools (Adobe Suite, Procreate, and other Adobe tools) (11), marketing and self-promotion (8), computer skills (8), 3D software and printing (5), craft skills (9), music and singing skills (6), photography/video editing and production (9), communication and people management (8), drawing and painting (7), creativity/creative thinking (6), painting (6), digital art tools, Adobe suite and Procreate (6), fashion and sewing (5), time management and effectiveness (5). In total, the participants listed 165 comments.

Those related to entrepreneurial and transversal skills are communication, learning, time management, learning tools, and intuition (mentioned only once). The skills accord with the skills mentioned by the experts on the CE.

What skills and tools the workshop participants would want to learn included marketing and self-promotion (9); craft skills (8); photography/video editing and production (8); speaking, communication, and languages (6); self-regulation and mindfulness (6); digital art tools, Adobe suite, and Procreate (5); business and project management (5); fashion and sewing (5); creative writing (4); 3D skills and sculpture (4); time management and effectiveness (3); audio, music, and singing skills (4); drawing and painting (3); information and data processing (2); being curious (2). In total, 89 skills were mentioned.

It took much work for the participants to separate skills and tools. Thus, some overlap is visible. The list is focused on the entrepreneurial skills that are pushed by accelerators and training centres. As discussed above, within the ecosystem theme, learning marketing and business strategies takes much time away from the actual work—an assistant would be better. Van Laar et al. [

17] found that managers could not mention how skills should be learned; however, in our study, the practitioners knew how and where they learned.

Learning habits are diverse. The following methods were listed: through practice and experience (7); through networks, or from friendly masters/older professionals or teachers (6); with colleagues (3); from watching videos (3); through creativity (3); and through trial and error (3). The topic had 30 comments in total.

Where participants learn provided the following list: social media such as Instagram, or courses, workshops, and master classes (4); and separately also mentioned YouTube, and blogs (e.g., tutorials from Google) (7); work environment/colleagues (3); in transit/during travels (3); from university (3); online courses (2); at home (3); in nature, in public, or everywhere (3). In total, there were 37 post-its for this topic.

Compared to the experts on the CE that offered mentoring, courses, programmes, and workshops, the creatives described multitudinous possibilities for learning.

RQ2: How and why do creative practitioners see that they can share, collaborate, and learn from one another and from other sectors?

Collaboration and sharing resources, knowledge, and skills are discernible in the participants’ learning habits and places. The following indicates how the creatives prefer to practise knowledge transfer: through networks, or from friendly masters/older professionals and teachers (6); with colleagues (3); through courses, workshops, and master classes (4); from communication with other artists, through exhibitions by analysing works, from work colleagues, or hanging with peers (mentioned one time). The list presents many informal ways of creating knowledge together. In the discussion, the following was mentioned: “common values, common vision, ethics for collaborations, some kind of level of expertise, work with people better than you otherwise how can you grow, you can also teach your knowledge then you also grow yourself.”—WS3(18). It relates to diversity, open-mindedness, better communication between people, and helping people live their own lives. There were wishes from the creatives that the facilitators of the workshops would “create this kind of support club for us to talk together”—WS3(22).

The other issues that were discussed were trading and providing favours for each other. As discussed above, the list of professions with whom trading and sharing is possible is endless. The participants also felt that artistic and creative people could collaborate with everybody else (WS1(19)). The aspects that can make collaboration and ecosystems sustainable are shared values, a common vision, ethics for collaborations, and a level of expertise (WS3(18)). In recent studies, a shared vision is critical to keep ecosystems growing [

47]. However, WS2(17) also mentioned the need for common ground and mutual respect. The participants’ values back up their visions of collaboration and ecosystems. These are, for instance, community, a common vision, more use of social artwork, safety to make the audience more mindful and liberal, acceptance, flexibility, creativity, and freedom. It has commonalities with the conceptual discussion of Pratt [

12] on the similarities between the circular economy and creative ecosystems.

It is a promising direction for the future of ecosystems. However, the existing players need to acknowledge the creatives’ needs more in Estonia. From the existing players (intermediaries), those who should be offering some funding, training, and support for cross-sectoral ecosystems that are worth mentioning are museums, galleries, festivals (13), funding agencies, incubators, ministries (12), educational institutions (2), and towns (2).

Oksanen et al. [

5] stress the importance of non-sequential processes, which can emerge and transform into several emerging and existing business ecosystems. It means that an acknowledged bottom-up approach is needed that would be more robust than the one currently visible in Estonia. In addition, dependency relationships lead to feedback loops of causality and enable self-organisation where a shared vision is crucial. The support should be continuing and the funding should be long-term. These needs align with the imaginative basis of ecosystems of the participatory co-design workshop participants, for instance, universal income, transparency, reliability, shared values, and common ground.

5.3. Discussion and Limitations of the Study

There are similarities in the structures of the intermediaries that train, fund, and connect with policy-makers within the context of the local, regional, and national ecologies, as described by Dent et al. [

13]. Our study involved the significant Estonian players in the field of intermediaries. In addition to the repertoire of services, most activities are similar; they provide training, networking, funding, and the gathering of feedback on the success of the training and networking. However, when listening to creatives’ needs, more attention should be paid to the Estonian context. It is important to provide the training and network activities as usual and check if they are fulfilled, as well as which kinds of activities the creatives would see as beneficial. The study data revealed that while training is directed towards teaching managerial and entrepreneurial skills to creative economy actors, they themselves preferred to learn how to gain the resources to hire someone to carry out the managerial work, which conforms with the finding from Van Laar et al. [

17]. Training and networking should be directed towards supporting professional growth and hiring specialists for marketing and strategy building. Another area for improvement was seen in the participants’ perceived skills and learning habits. Learning is directed towards enhancing the profession rather than towards acquiring entrepreneurial skills. Therefore, some of the funding and training are not meeting the actual needs of the creatives. Dent et al. [

13] (p. 13) studied Central Europe, especially the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (UK), and found an important difference: creatives in Central Europe receive more national funding support than those based in the UK, Eastern Europe, and Greece, which rely more on self-funding models. The self-funding model is strong in Estonia, too.

The values that the participants mentioned differ from the current aims for growth; the values presented by the workshop participants come closer to degrowth values [

12,

15,

47]. The values that were mentioned were the following (

Appendix A,

Table A6):

Simplicity, connecting with nature, sense of belonging, open-mindedness, safety, diversity and acceptance. Ecosystems should be grounded on mutual benefits, reliability, cost reduction, flexibility, creativity, and freedom. Concerning the ecosystems, the workshop participants mentioned the following: “

common values, common vision, ethics for collaborations, some kind of level of expertise, work with people better than you otherwise how can you grow, you can also teach your knowledge then you also grow yourself.”—WS3(18). These aspects relate to diversity, open-mindedness, better communication between people, and helping people live their own lives. It is a promising direction for the future of ecosystems. From the intermediaries, those who should be offering some funding, training, and support for cross-sectoral ecosystems are museums, galleries, festivals (13), funding agencies, incubators, ministries (12), educational institutions (2), and towns (2). In addition, conceptual thinking should be extended towards the “immaterial dimensions of culture, its formations and transformations; and the sustainability of the skills, craft, practices and techniques (their teaching and training) that also animate all making.” [

12] (p. 7).

Oksanen et al. [

5] stress the importance of non-sequential processes, which can emerge and transform into several emerging and existing business ecosystems. It means that an acknowledged bottom-up approach is needed that is more robust than the one currently visible in Estonia. In addition, dependency relationships lead to feedback loops of causality and enable self-organisation where a shared vision is crucial. The support should be continuing and the funding should be long-term. These needs align with the imaginative basis of ecosystems of the participants of the participatory co-design workshop, for instance, universal income, transparency, reliability, shared values, and common ground. Dent et al. [

13], de Bernard et al. [

15], and Lin [

11] also recommend long-term strategies and funding. Our study found the same challenge. Most funding, training, and networking are sporadic; they are aimed at specific current issues, whereas it would be beneficial to have a long-term strategy. It is good to have training on marketing, managing, and providing networking, but these should be tied to a strategy of structural changes and 21st-century skills and sustainability. However, focusing on structural changes might demand societal changes, which is not easy, but is implied by the results of our study.

The practical findings were that the creatives wished to know more about novel technologies such as artificial intelligence and NFTs. Also, both are challenging in their societal values. As mentioned, the creatives had values such as diversity, equality, sharing, and recycling, which align with degrowth ideas and universal income. These were connected to resource sharing in the form of ecosystems. We see it is related to what Comunian et al. [

47] state in de Bernard et al. [

15] as a “restrictive nature –for giving priority to neo-liberal growth-oriented accounts of culture and creativity compared to not-for-profit or community-driven ones” (p. 338). They also pointed out that “the top-down policy-led framings can fail to recognise the messy realities of cultural and creative activity and the diversity of ways in which culture and creativity are part of people’s lives.” [

15] (p. 338). It nicely describes what our study revealed. Many emerging ecosystems are built from the bottom-up, but what are officially called ecosystems are—for instance, the Estonian Start-up Ecosystem—top-down constructions. It provides an intriguing future research direction on the values of creative economies regarding environmental challenges [

47,

48,

49]; that is, the CE not as an instrumental value but also a value in itself, which HERA has announced in Crisis—Perspectives from the Humanities.

On limitations, the qualitative data are abundant, but they are local, and thus generalising the results and conclusions cannot be directly applied to other countries. However, the results provide a well-grounded direction for other countries and cultures. Another limitation is that the gender division is favourable for females. In the co-design workshops and semi-structured interviews, females were dominant. In total, we had six men and seventeen females. In the co-design workshops, we had five men and eleven women, and one male and six females in the semi-structured interviews. It is impossible to say which kind of bias this might have provided, but as it is known, it should be kept in mind when investigating the recommendations and results of other countries and cultures. The number of participants could have been more significant. Nevertheless, it was saturated for Estonia, as we ended up with the same person through different paths. Another aspect is that the participatory approach aims for empowerment and insight [

41]. Thus, success is measured by the novel insights gained and the empowerment of the participants. We can safely state that we achieved both insight and empowerment, since one of the wishes was to “create this kind of support club for us to talk together”—WS3(22).

Yet, another limitation was that, on average, the participants were under 50 years old, except for one person. Our participants were potentially more digitally inclined than the older generation. Nevertheless, the one person over fifty was highly knowledgeable about current and emerging technologies.