Quantifying Sustainability and Landscape Performance: A Smart Devices Assisted Alternative Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

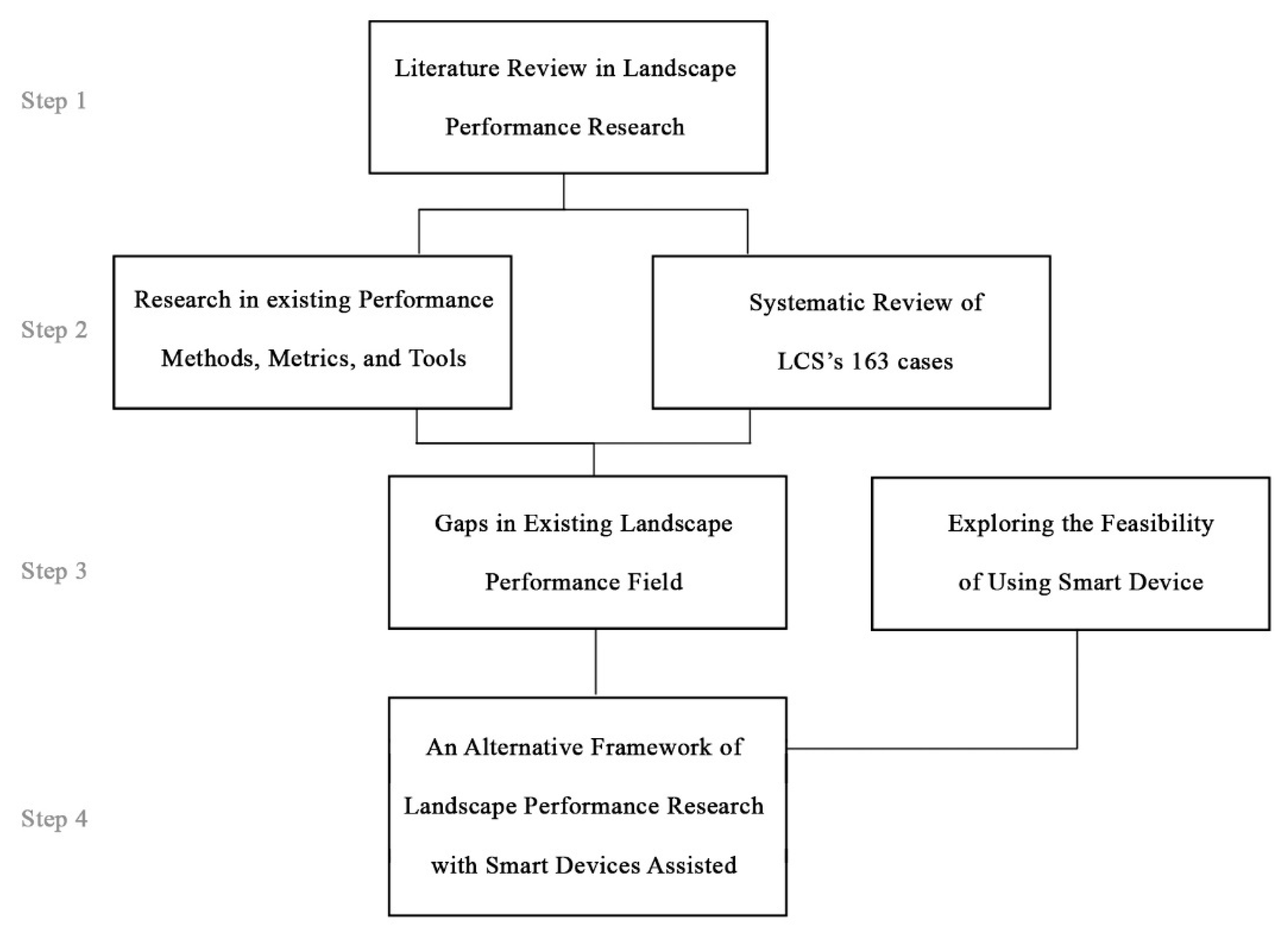

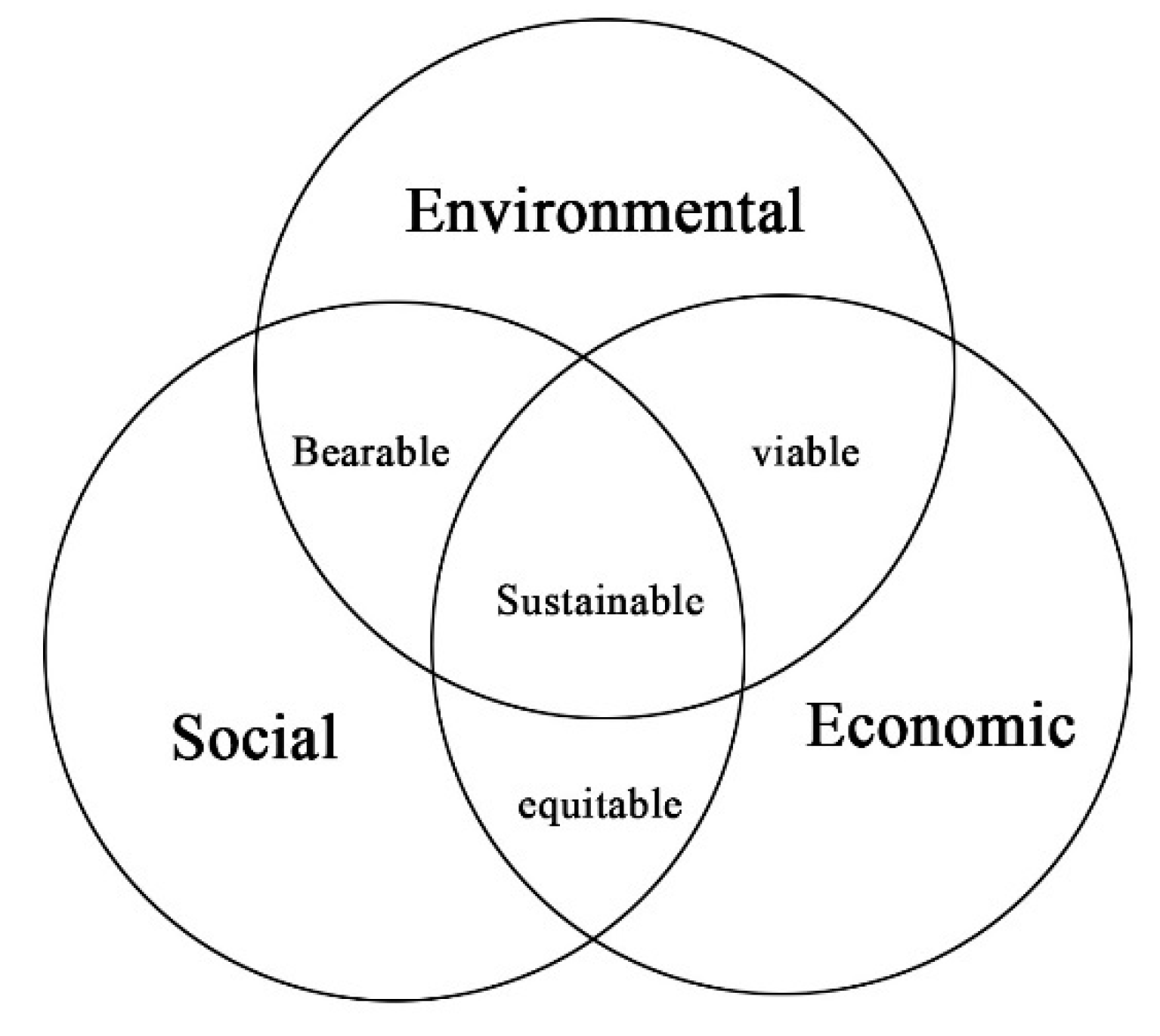

2. Research Framework and Research Questions

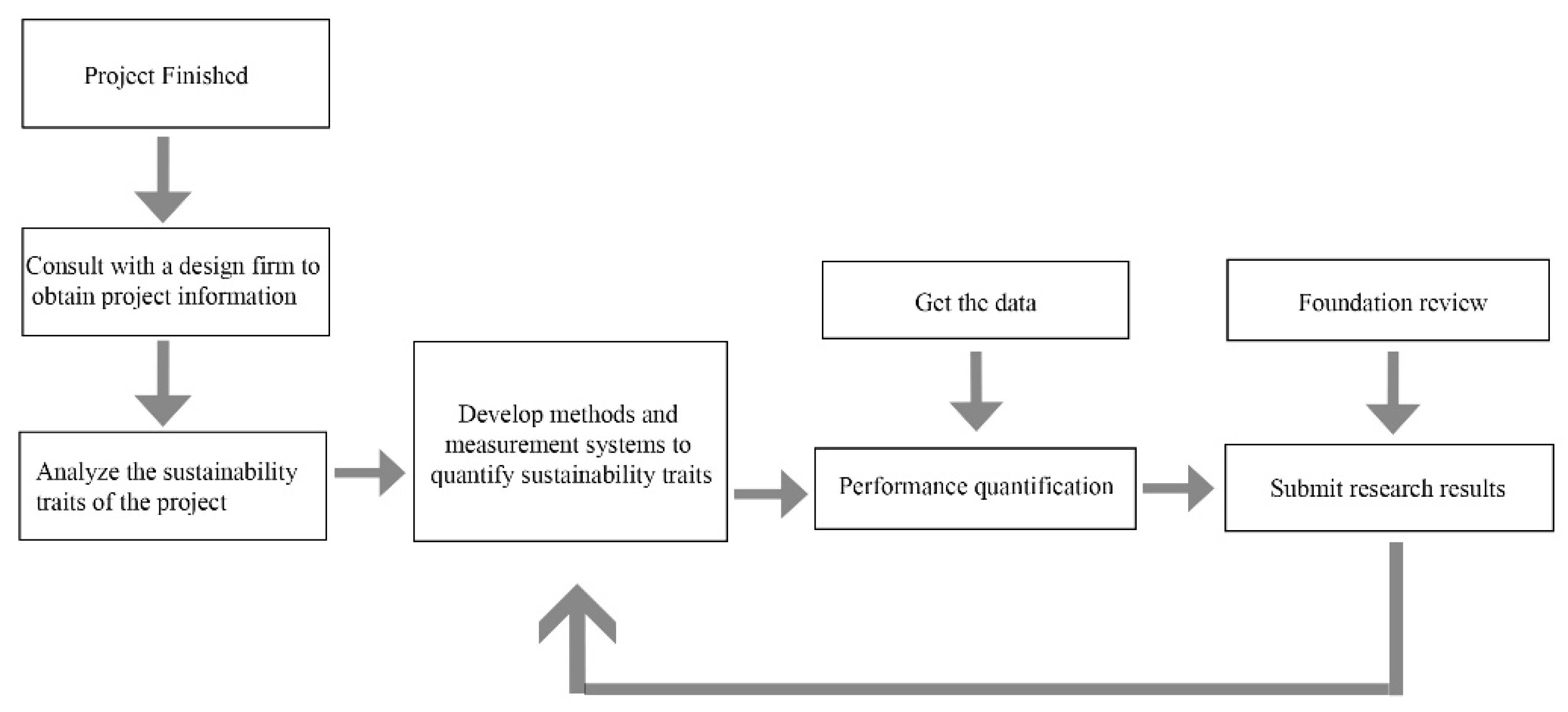

3. Existing Landscape Performance Research Method

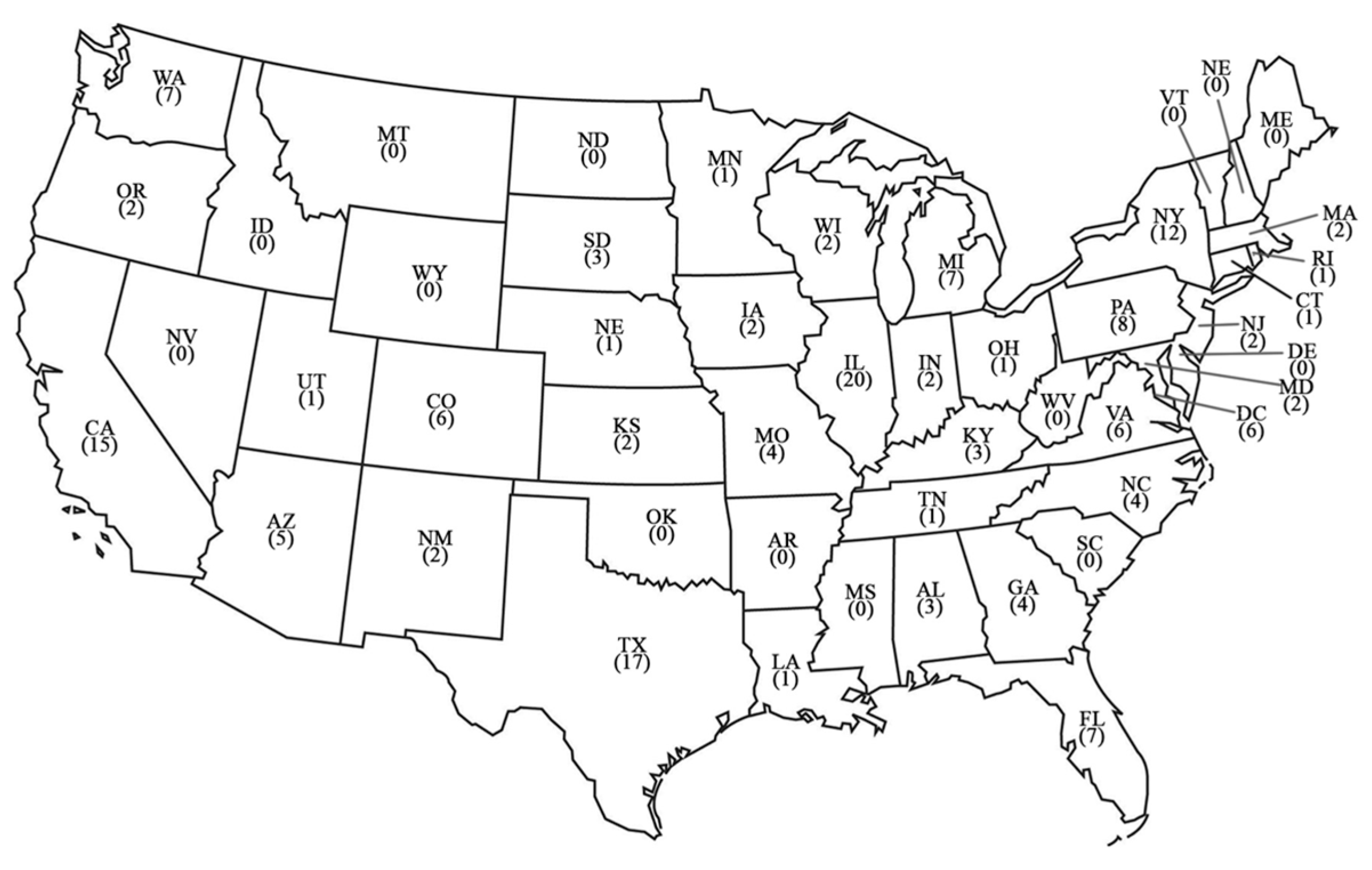

3.1. Case Study Investigation

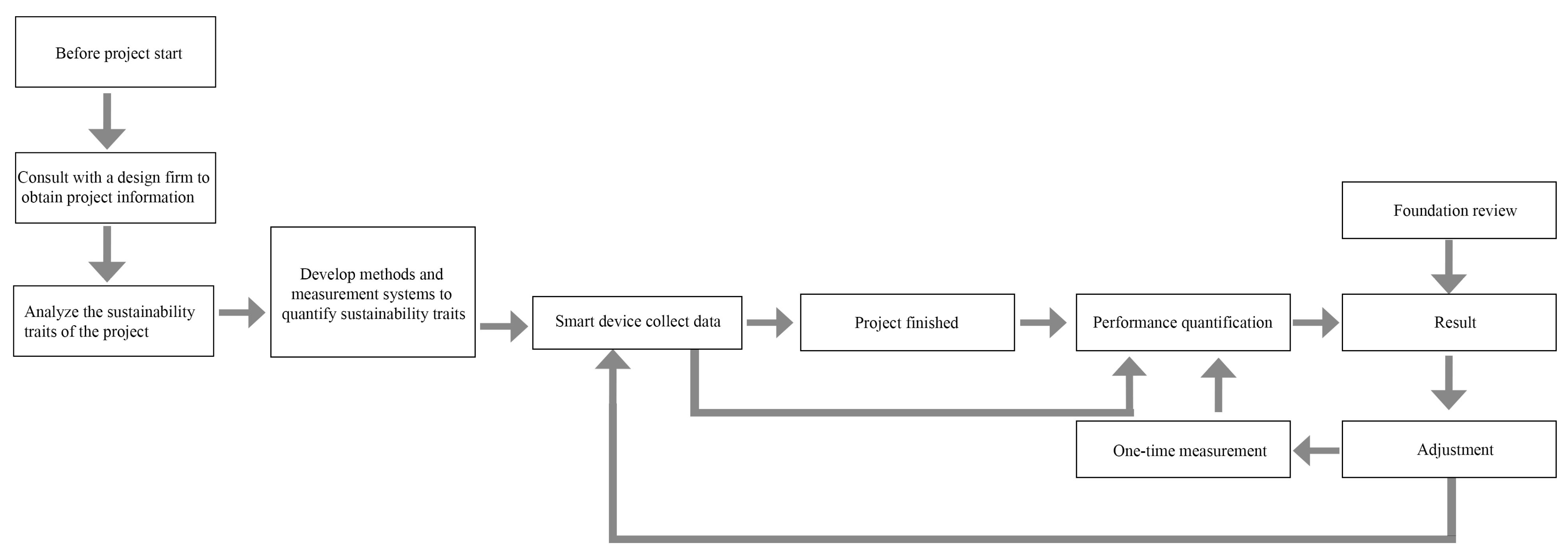

3.2. Gaps in Frameworks, Metrics, and Methodologies

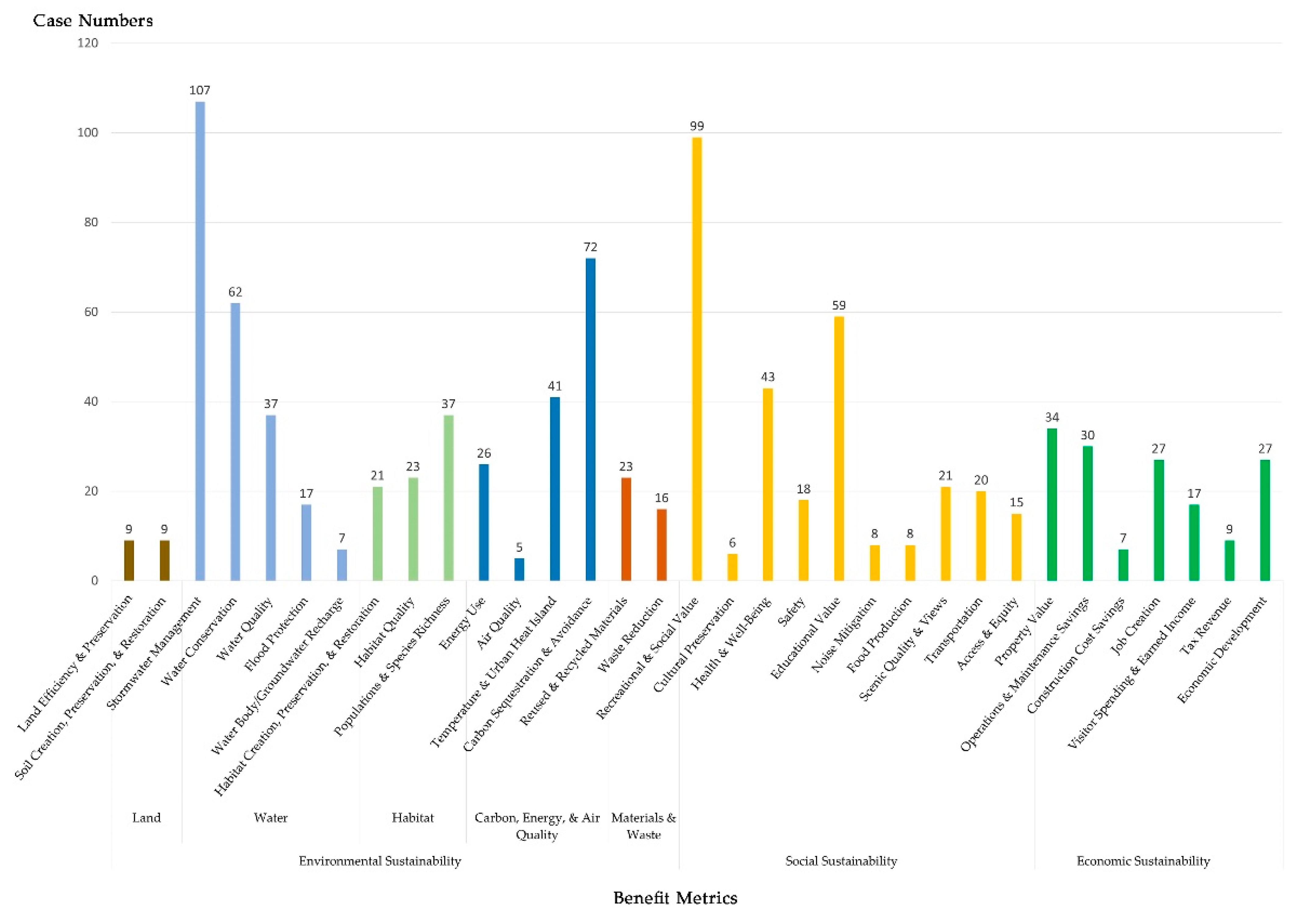

3.3. CSI Gap Analysis through Existing Cases

3.4. One-Time Measurement

4. Landscape Performance Quantification Tools

4.1. Gaps in LPS Online Tools

4.2. Survey in LPS Online Tools

4.3. Tools in Each Benefit Metric

5. Smart Devices to Assess Landscape Performance

5.1. Cases for Quantifying Performance of Smart Devices

5.1.1. Applications in the Field of Architecture

5.1.2. Applications in the Field of Landscape Performance

5.2. Utilized Smart Devices

5.3. Potential Limitations of Solely Using Smart Devices

6. An Alternative Landscape Performance Measuring Framework

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shafique, M.; Kim, R.; Rafiq, M. Green roof benefits, opportunities and challenges—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, E.; Comín, F.A. Urban green infrastructure and sustainable development: A review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Bakaric, J.; Jeffrey-Bailey, T. The urban heat island effect, its causes, and mitigation, with reference to the thermal properties of asphalt concrete. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 197, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.R.; Hill, K. (Eds.) Ecology and Design: Frameworks for Learning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, A. Looking backwards, looking forwards. Landsc. Res. 2014, 39, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, F. Frontiers in urban ecological design and planning research. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.D.; Corry, R.C. Evidence-based landscape architecture: The maturing of a profession. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Amodio, D.M. Political ideology as motivated social cognition: Behavioral and neuroscientific evidence. Motiv. Emot. 2012, 36, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landscape Performance Series. 2023. Available online: https://www.landscapeperformance.org/about-landscape-performance (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Canfield, J.; Yang, B. Reflections on developing landscape performance case studies. Landsc. Res. Rec. 2014, 1, 310–317. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Li, S.; Binder, C. A research frontier in landscape architecture: Landscape performance and assessment of social benefits. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. Landscape performance evaluation in socio-ecological practice: Current status and prospects. Socio-Ecol. Pract. Res. 2020, 2, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Kim, M. Improving Landscape Performance Measurement: Using Smart Sensors for Longitudinal Air Quality Data Tracking. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, K.; Buck, L.; de Graaf, M.; Minang, P.; van Oosten, C.; Zagt, R. Participatory planning, monitoring and evaluation of multi-stakeholder platforms in integrated landscape initiatives. Environ. Manag. 2018, 62, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiele, A.; Esfahani, S.; Covington, J. Design and development of a low-cost, portable monitoring device for indoor environment quality. J. Sens. 2018, 2018, 5353816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, M.H. Landscape Performance of Built Projects: Comparing Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Published Metrics and Methods. Landsc. Archit. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, D.X.; Li, M.H. Research development of landscape performance assessment in America. Landsc. Archit. 2015, 1, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield, J.; Yang, B.; Whitlow, H. Evaluating Landscape Performance—A Guidebook for Metrics and Methods Selection; Landscape Architecture Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y. Enhancing Quantification of a Landscape Project’s Environmental, Economic and Social Benefits: A Study of Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Landscape Performance Series. Doctoral Dissertation, Texas A&M University. Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haines-Young, R. Sustainable development and sustainable landscapes: Defining a new paradigm for landscape ecology. Fennia 2000, 178, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ozdil, T.R. Social value of urban landscapes: Performance study lessons from two iconic Texas projects. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2016, 4, 12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Terkenli, T.S.; Gkoltsiou, A.; Kavroudakis, D. The interplay of objectivity and subjectivity in landscape character assessment: Qualitative and quantitative approaches and challenges. Land 2021, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Landscape sustainability science: Ecosystem services and human well-being in changing landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostrubiec, V.; Zanone, P.G.; Fuchs, A.; Kelso, J.S. Beyond the blank slate: Routes to learning new coordination patterns depend on the intrinsic dynamics of the learner\textemdashexperimental evidence and theoretical model. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landscape Performance Series. 2023. Available online: https://www.landscapeperformance.org/benefits-toolkit (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Modi, S.K. Perspectives on Environmental Landscape Performance Indicators and Methods: Learning from Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Case Study Investigation Program; The University of Texas at Arlington: Arlington, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bixler, R.P.; Johnson, S.; Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Reuling, M.; Curtin, C.; Romolini, M.; Grove, J.M. Networks and landscapes: A framework for setting goals and evaluating performance at the large landscape scale. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, M.E.; Swaffield, S. Landscape Architectural Research: Inquiry, Strategy, Design; John Wiley Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, M. A case study method for landscape architecture. Landsc. J. 2001, 20, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.D. Landscape Architecture Theory: An Evolving Body of Thought; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA,, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, S.; Qilong, M.; Du, J. Architecture of wireless sensor networks for environmental monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Workshop on Education Technology and Training 2008 International Workshop on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, Shanghai, China, 21–22 December 2008; Volume 1, pp. 579–582. [Google Scholar]

- Schieweck, A.; Uhde, E.; Salthammer, T.; Salthammer, L.C.; Morawska, L.; Mazaheri, M.; Kumar, P. Smart homes and the control of indoor air quality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzzadeh, M.S.; Nguyen, A.; Kosmala, M.; Swanson, A.; Palmer, M.S.; Packer, C.; Clune, J. Automatically identifying, counting, and describing wild animals in camera-trap images with deep learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E5716–E5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kays, R.; Tilak, S.; Kranstauber, B.; Jansen, P.A.; Carbone, C.; Rowcliffe, M.J.; Fountain, T.; Eggert, J.; He, Z. Monitoring wild animal communities with arrays of motion sensitive camera traps. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1009.5718. [Google Scholar]

- Bibri, S.E.; Krogstie, J. Environmentally data-driven smart sustainable cities: Applied innovative solutions for energy efficiency, pollution reduction, and urban metabolism. Energy Inform. 2020, 3, 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Low, K.S.; Win, W.N.N.; Er, M.J. Wireless sensor networks for industrial environments. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Modelling, Control and Automation and International Conference on Intelligent Agents, Web Technologies and Internet Commerce (CIMCA-IAWTIC’06), Vienna, Austria, 28–30 November 2005; Volume 2, pp. 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Firouzi, F.; Farahani, B.; Marinšek, A. The convergence and interplay of edge, fog, and cloud in the AI-driven Internet of Things (IoT). Inf. Syst. 2022, 107, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzira, F.M.; Bankole, F. Application of Social Media Analytics in the banking sector to drive growth and sustainability: A proposed integrated framework. In Proceedings of the 2018 Open Innovations Conference (OI), Johannesburg, South Africa, 3–5 October 2018; pp. 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Almalki, F.A.; Alsamhi, S.H.; Sahal, R.; Hassan, J.; Hawbani, A.; Rajput, N.S.; Saif, A.; Morgan, J.; Breslin, J. Green Iot for Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Smart Cities: Future Directions and Opportunities. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2021, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoop, G. Using Land-Use Data to Improve Automatic Classification Accuracy of Machine Learning Models for Classifying Outdoor Sport Activities in GNSS-Tracks. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Angelidou, M.; Psaltoglou, A.; Komninos, N.; Kakderi, C.; Tsarchopoulos, P.; Panori, A. Enhancing sustainable urban development through smart city applications. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2018, 9, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, D.S.; Rose, A.L.; Arvindan, S.; Revathy, J.; Amuthadevi, C. Automation systems in smart buildings: A review. J. Ambient Intell. Human Comput, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateeq, M.; Ishmanov, F.; Afzal, M.K.; Naeem, M. Multi-parametric analysis of reliability and energy consumption in IoT: A deep learning approach. Sensors 2019, 19, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hong, D.; Wang, H. Relation inference among sensor time series in smart buildings with metric learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 4683–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzoli, A.; Piscitelli, M.S.; Gorrino, A.; Ballarini, I.; Corrado, V. Data analytics for occupancy pattern learning to reduce the energy consumption of HVAC systems in office buildings. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 35, 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Canteli, J.R.; Ulyanin, S.; Kämpf, J.; Nagy, Z. Fusing TensorFlow with building energy simulation for intelligent energy management in smart cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Liens D’accessibilité. EPFL. (22 October 2015). Available online: https://archiveweb.epfl.ch/eflum.epfl.ch/ (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Beigl, M.; Krohn, A.; Riedel, T.; Zimmer, T.; Decker, C.; Isomura, M. The uPart Experience: Building a Wireless Sensor Network. In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Information Processing in Sensor Networks (IPSN 2006), Poster Session of SPOT Track, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–21 April 2006; pp. 366–373. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, T.; Ishizuka, H.; Ito, K.; Ishida, Y.; Miyazaki, S.; Mihirogi, O.; Tobe, Y. Uscan: Towards Fine-Grained Urban Sensing. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Real Field Identification (RFId2007), Tokyo, Japan. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=f5533cb93e0a62f43ad3ec22bfdd3f68ada1cdb4 (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Shen, Z.; Kim, M. Longitudinal Water Pollution Monitoring and Retention Pond Capacity Assessment Using Smart Devices. 2023; J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Sarkar, A.; Ather, D.; Raj, D. Temperature Based Automatic Fan Speed Control System using Arduino. SSRN, 2022; SSRN 4159188. [Google Scholar]

- Arduino, S.A. Arduino; Arduino LLC.: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; p. 372. Available online: https://search.iczhiku.com/paper/TFzDJhGhd6VMaDsI.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Perera, C.; Qin, Y.; Estrella, J.C.; Reiff-Marganiec, S.; Vasilakos, A.V. Fog computing for sustainable smart cities: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2017, 50, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hyder, K.; Rossberg, A.G.; Allen, J.I.; Austen, M.C.; Barciela, R.M.; Bannister, H.J.; Blackwell, P.G.; Blanchard, J.L.; Burrows, M.T.; Defriez, E.; et al. Making modelling count-increasing the contribution of shelf-seas community and ecosystem models to policy development and management. Mar. Policy 2015, 61, 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano, R.; Reinhart, W.; Gevaudan, J.P. Smart cities built with smart materials. Science 2021, 371, 1200–1201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Puskás, N.; Abunnasr, Y.; Naalbandian, S. Assessing deeper levels of participation in nature-based solutions in urban landscapes–A literature review of real-world cases. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 210, 104065. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasena, N.S.; Mallawaarachchi, H.; Waidyasekara, K.G.A.S. Stakeholder analysis for smart city development project: An extensive literature review. MATEC Web Conf. 2019, 266, 06012. [Google Scholar]

| Sustainability | Type of Benefit | Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Sustainability (155) | Land | Land Efficiency and Preservation |

| Soil Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | ||

| Water | Stormwater Management | |

| Water Conservation | ||

| Water Quality | ||

| Flood Protection | ||

| Water Body/Groundwater Recharge | ||

| Habitat | Habitat Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | |

| Habitat Quality | ||

| Populations and Species Richness | ||

| Carbon, Energy, and Air Quality | Energy Use | |

| Air Quality | ||

| Temperature and Urban Heat Island | ||

| Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ||

| Materials and Waste | Reused and Recycled Materials | |

| Waste Reduction | ||

| Social Sustainability (143) | N/A | Recreational and Social Value |

| Cultural Preservation | ||

| Health and Well-Being | ||

| Safety | ||

| Educational Value | ||

| Noise Mitigation | ||

| Food Production | ||

| Scenic Quality and Views | ||

| Transportation | ||

| Access and Equity | ||

| Economic Sustainability (105) | N/A | Property Value |

| Operations and Maintenance Savings | ||

| Construction Cost Savings | ||

| Job Creation | ||

| Visitor Spending and Earned Income | ||

| Tax Revenue | ||

| Economic Development |

| Sustainability | Type of Benefit | Metric | Case Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Sustainability (155) | Land | Land Efficiency and Preservation | 9 |

| Soil Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | 9 | ||

| Water | Stormwater Management | 107 | |

| Water Conservation | 62 | ||

| Water Quality | 37 | ||

| Flood Protection | 17 | ||

| Water Body/Groundwater Recharge | 7 | ||

| Habitat | Habitat Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | 21 | |

| Habitat Quality | 23 | ||

| Populations and Species Richness | 37 | ||

| Carbon, Energy, and Air Quality | Energy Use | 26 | |

| Air Quality | 5 | ||

| Temperature and Urban Heat Island | 41 | ||

| Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | 72 | ||

| Materials and Waste | Reused and Recycled Materials | 23 | |

| Waste Reduction | 16 | ||

| Social Sustainability (143) | N/A | Recreational and Social Value | 99 |

| Cultural Preservation | 6 | ||

| Health and Well-Being | 43 | ||

| Safety | 18 | ||

| Educational Value | 59 | ||

| Noise Mitigation | 8 | ||

| Food Production | 8 | ||

| Scenic Quality and Views | 21 | ||

| Transportation | 20 | ||

| Access and Equity | 15 | ||

| Economic Sustainability (105) | N/A | Property Value | 34 |

| Operations and Maintenance Savings | 30 | ||

| Construction Cost Savings | 7 | ||

| Job Creation | 27 | ||

| Visitor Spending and Earned Income | 17 | ||

| Tax Revenue | 9 | ||

| Economic Development | 27 |

| Toolkits | Metrics | Payment Needed | Difficulty to Use | Result Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Geospatial Watershed Assessment (AGWA) Tool v 3.0 | Water Quality | ⚪ | 2 | ⚫️ |

| Stormwater Management | ||||

| Soil Creation, Preservation, and Restroration | ||||

| Carbon Conscience | Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ⚪ | 2 | ⚪ |

| COMET-Farm | Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ⚪ | 1 | ⚪ |

| Construction Carbon Calculator | Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ⚪ | 2 | ⚫️ |

| Decking Cost Calculator | Construction Cost Savings | ⚪ | 1 | ⚪ |

| Operations and Maintenance Savings | ||||

| eBird | Populations and Species Richness | ⚪ | 1 | ⚪ |

| Erosion Control Calculator | Construction Cost Savings | ⚪ | 1 | ⚪ |

| GBRL Green Roof Energy Calculator (v 2.0) | Operations and Maintenance Savings | ⚪ | 2 | ⚫️ |

| Energy Use | ||||

| Stormwater Management | ||||

| i-Tree Eco (v 6) | Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ⚪ | 2 | ⚪ |

| Air Quality | ||||

| Energy Use | ||||

| i-Tree Streets (v 5.1) | Property Values | ⚪ | 2 | ⚪ |

| Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ||||

| Air Quality | ||||

| Energy Use | ||||

| Stormwater Management | ||||

| iNaturalist | Habitat Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | ⚪ | 1 | ⚪ |

| Populations and Species Richness | ||||

| Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST) v 3.3.3 | Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ⚪ | 2 | ⚪ |

| Populations and Species Richness | ||||

| Water Quality | ||||

| Soil Creation, Preservation, and Restrotation | ||||

| Long-Term Hydrologic Impact Analysis | Water Quality | ⚪ | 1 | ⚪ |

| Stormwater Management | ||||

| National Stormwater Calculator | Stormwater Management | ⚪ | 2 | ⚪ |

| National Stormwater Management Calculator | Operations and Maintenance Savings | ⚪ | 2 | ⚪ |

| Stormwater Management | ||||

| Pathfinder: Landscape Carbon Calculator | Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ⚪ | 3 | ⚫️ |

| Access and Equity | ||||

| Food Production | ||||

| Transportation | ||||

| Public Life Tools | Recreational and Social Value | N/A | 1 | ⚪ |

| Rainwater Harvesting Calculator | Water Conservation | ⚪ | 2 | ⚪ |

| Stormwater Management | ||||

| Recycled Content (ReCon) Tool | Reused/Recycled Materials | N/A | 1 | ⚪ |

| Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ||||

| Energy Use | ||||

| Recycling and Reusing Landscape Waste Cost Calculator | Reused/Recycled Materials | ⚪ | 1 | ⚪ |

| Operations and Maintenance Savings | ||||

| Waste Reduction | ||||

| Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ||||

| Air Quality | ||||

| Energy Use | ||||

| Water Conservation | ||||

| Resource Conserving Landscaping Cost Calculator | Construction Cost Savings | ⚪ | 1 | ⚪ |

| Operations and Maintenance Savings | ||||

| Water Conservation | ||||

| SPAW Field and Pond Hydrology Model | Water Body/Groundwater Recharge | N/A | 2 | ⚪ |

| Stormwater Management | ||||

| Sub-Surface Drip Irrigation Cost Calculator | Construction Cost Savings | ⚪ | 1 | ⚪ |

| Operations and Maintenance Savings | ||||

| Water Conservation | ||||

| System for Observing Physical Activity and Recreation in Natural Areas (SOPARNA) | Health and Well-Being | N/A | 2 | ⚪ |

| Recreational and Social Value | ||||

| System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth (SOPLAY) | Health and Well-Being | N/A | 2 | ⚪ |

| Recreational and Social Value | ||||

| System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities (SOPARC) | Health and Well-Being | N/A | 1 | ⚪ |

| Recreational and Social Value | ||||

| The Value of Green Infrastructure: A Guide to Recognizing Its Economic, Social and Environmental Benefits | Property Values | N/A | 2 | ⚪ |

| Educational Value | ||||

| Recreational and Social Value | ||||

| Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ||||

| Temperature and Urban Heat Island | ||||

| Air Quality | ||||

| Energy Use | ||||

| Food Production | ||||

| Water Quality | ||||

| Water Conservation | ||||

| Stormwater Management | ||||

| Toolkit for Ecosystem Service Site-Based Assessment (TESSA) v3.0 | Soil Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | ⚪ | 3 | ⚫️ |

| Water Conservation | ||||

| Habitat Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | ||||

| Universal Floristic Quality Assessment Calculator | Habitat Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | ⚪ | 2 | ⚪ |

| Habitat Quality | ||||

| Vegetable Garden Value Calculator | Food Production | N/A | 1 | ⚪ |

| Waste Reduction Model (WARM) v14 | Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | ⚪ | 2 | ⚫️ |

| Reused/Recycled Materials | ||||

| Waste Reduction | ||||

| Energy Use | ||||

| Water Harvesting Calculator | Water Conservation | ⚪ | 2 | ⚪ |

| Sustainability | Type of Benefits | Metrics | Case Numbers | Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Benefits | Land | Land Efficiency and Preservation | 9 | Third-party data, self-calculation, watershed modeling |

| Soil Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | Soil Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | 73 | L-THIA model, soil survey data, infiltration measurements, third-party data, (SWC) software application, soil borings, sustainable SITES program, Garden Assessment Tool for Evaluators (GATE), Sustainable Sites Initiative (SITES), Cut/fill calculations | |

| Water | Stormwater Management | 107 | Caliper and measuring tape for measuring trees’, Vflo model, “Diameter at Breast Height” (DBH), secondary data provided by the Philadelphia Water, EPA national stormwater calculator, Autodesk’s hydraflow hydrographs stormwater modeling software, rainfall frequency atlas, infiltration beds, self-calculation, stormwater treatment model, L-THIA, stormwater spreadsheet tool 3.0, InfoWorks model, temporary flow meters, rational equation method, hydraulic modeling software (XPSWMM), land cover delineation table, permeable pavers, StormNET version 4.18.7, FlowMaster version 5.15, rainfall frequency atlas of the midwest, hydrologic and hydraulic modeling, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), biofiltration and infiltration equation | |

| Water Conservation | 61 | Self-calculation, LEED submittal documentation, water budget tool, cutting-edge irrigation system, WaterSense program, gravel bed, SimTraffic | ||

| Water Quality | 36 | Self-calculation, L-THIA Model, BMPs, LaMotte water quality monitoring kit, BNIM, TR-55 method, flow meters, measurement of pump usage, water meter totalizer | ||

| Flood Protection | 17 | USDA and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers modeling software, HEC RAS modeling, LiDAR-derived digital elevation models, riparian bank stabilization techniques, hydrodynamic separator, NOAA sea level rise viewer, LEED, bank erosion hazard index (BEHI), underdrain system | ||

| Water Body/Groundwater Recharge | 7 | Rational runoff coefficient | ||

| Habitat | Habitat Creation, Preservation, and Restoration | 21 | USDA, third-party data, i-Tree Eco v6, survey, plant ID method, restoration techniques, aerial imagery tracing | |

| Habitat Quality | 23 | Monitoring to document, onsite inventory, species count, USEPA | ||

| Populations and Species Richness | 37 | Universal floristic quality assessment tool—coefficients of conservatism, MidAtlantic coastal plain database, secondary data, eBird, Floristic Quality Index, i-Tree Eco v6, tree inventory, LEED NCv2.2, biodiversity monitoring, insect vacuum, bird species records, GIS | ||

| Carbon, Energy, and Air Quality | Energy Use | 25 | Green roof energy calculator, solar electricity generation data, photocell sensors, USGBC new construction and renovation reference guide, solar reflectance index (SRI) | |

| Air Quality | 5 | i-Tree Eco (v 6), i-Tree Streets (v 5.1), recycling and reusing landscape waste cost calculator | ||

| Temperature and Urban Heat Island | 39 | USGBC new construction and renovation reference guide, Actron IR thermometer Pro, Kintrex infrared thermometer IRT0421, thermometer, infrared thermometer, SRI calculator, GIS, kriging method, Acu-Rite Wireless thermometers | ||

| Carbon Sequestration and Avoidance | 76 | i-Tree eco software—version 6, carbon sequestration calculation, national tree benefit calculator, EPA and EIA websites | ||

| Materials and Waste | Reused and Recycled Materials | 57 | Greywater estimation, embodied energy calculation | |

| Waste Reduction | 16 | Glenstone, Chesapeake Bay program interim pollutant reduction accounting method, Waste Reduction Model (WARM) calculator | ||

| Social Benefits | N/A | Recreational and Social Value | 100 | Survey, social media, ParkServe, observations, Gehl Public Life tools, third-party data, visual impact assessment, System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth (SOPLAY) protocol, behavior mapping, StormTech publication, traffic counters |

| Cultural Preservation | 6 | Survey, self-calculation | ||

| Health and Well-Being | 44 | Survey, social media, Park Serve | ||

| Safety | 19 | Fortified roof, Google Earth Pro line measuring tool | ||

| Educational Value | 58 | SWMM | ||

| Noise Mitigation | 7 | Self-calculation | ||

| Food Production | 8 | Survey, GIS | ||

| Scenic Quality and Views | 22 | Survey | ||

| Transportation | 21 | Survey, traffic-calming techniques | ||

| Access and Equity | 15 | Survey, social media, and Park serve | ||

| Economic Benefits | NA | Property Value | 32 | GIS and Phila.gov database, self-calculation, survey |

| Operations and Maintenance Savings | 28 | Self-calculation, LEED submittal documentation, volunteer weeding, financial model reports | ||

| Construction Cost Savings | 6 | Contractor verified, self-calculation, survey, “Twisted Jacket” system, low-temperature thermal desorption (LTTD), RIMS II economic input-output model, cost savings analysis | ||

| Job Creation | 25 | Self-calculation, emerging professionals program | ||

| Visitor Spending and Earned Income | 13 | Self-calculation | ||

| Tax Revenue | 8 | Self-calculation | ||

| Economic Development | 26 | CB Richard ellis, Survey, GIS |

| Frameworks | Current Framework | Alternative Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Simplicity | Data Diversity |

| Accuracy | ||

| Quick results | Dynamism | |

| Cost-effectiveness | ||

| Limitations | Data limitations | Technical Requirements |

| Low reliability | ||

| Lack of dynamism | Data Processing Complexity | |

| High Labor and time costs | Types of Projects |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, Z.; Peng, X.; Du, C.; Kim, M. Quantifying Sustainability and Landscape Performance: A Smart Devices Assisted Alternative Framework. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713239

Shen Z, Peng X, Du C, Kim M. Quantifying Sustainability and Landscape Performance: A Smart Devices Assisted Alternative Framework. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):13239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713239

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Zhongzhe, Xingjian Peng, Chenlong Du, and Mintai Kim. 2023. "Quantifying Sustainability and Landscape Performance: A Smart Devices Assisted Alternative Framework" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 13239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713239

APA StyleShen, Z., Peng, X., Du, C., & Kim, M. (2023). Quantifying Sustainability and Landscape Performance: A Smart Devices Assisted Alternative Framework. Sustainability, 15(17), 13239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151713239