1. Introduction

Disasters, both natural and man-made, have increasingly become a global concern, necessitating effective disaster management practices to mitigate their impact on organizations and communities and bolster overall resilience. Organizational demographic characteristics, such as type, location, sector, and size, are pivotal to the success of managing disasters and shaping these practices. Indeed, these characteristics can influence an organization’s vulnerabilities, available resources, and capacity to respond to and recover from disasters [

1,

2]. Understanding these characteristics and their interplay with disaster management practices becomes crucial in this evolving landscape.

Given the intertwined nature of global economies and supply chains, effective disaster management goes beyond mere response and recovery; it encompasses preemptive strategies that ensure continuity in operations and supply chains. Operations and supply chain management are, therefore, critical to disaster management, directly impacting an organization’s ability to maintain continuity, manage disruptions, and ensure timely recovery [

3,

4,

5].

Organizations across different sectors, such as healthcare, oil and gas, education, and finance, are inherently structured with diverse operational natures. Consequently, they face unique disaster management challenges, especially considering their potential impact on critical infrastructure and services. It becomes evident that there is not a one-size-fits-all solution; the variability in operational impact across sectors necessitates sector-specific disaster management practices [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Moreover, the geographic location of an organization compounds these challenges. Similar to how sectors vary in their vulnerabilities, organizations situated in different regions confront distinct types of calamities, further emphasizing the need for tailored preparedness initiatives [

10]. Additionally, another significant factor that plays into this complexity is the size of an organization. Larger organizations might possess more resources but face the daunting task of implementing comprehensive disaster management practices on a grand scale, while smaller organizations might be more agile but resource-restrained [

11].

Addressing the gap in existing research, this study endeavors to answer how specific organizational characteristics (type, location, sector, and size) influence perceived operational and supply chain practices in disaster management within the Kuwaiti context and the unique challenges and opportunities these characteristics present throughout the disaster management cycle.

Despite ample research, a gap exists in studying Kuwaiti organizations, particularly in the realm of operations and supply chain practices in disaster management [

12]. Strategically situated in the northeastern part of the Arabian Peninsula, Kuwait’s unique geographic location and susceptibility to various types of disasters make it an ideal context for studying the relationship between organizational characteristics and disaster management practices.

Kuwait’s geographical vulnerability exposes it to various natural hazards, such as earthquakes, sandstorms, heat waves, and rain floods. This underscores the need for effective disaster management practices tailored to its specific challenges [

13]. Moreover, as a country with unique geographical vulnerabilities and an economy heavily reliant on industries such as oil and gas, finance, and trade [

14], the implications of ineffective disaster management can be severe. Poorly managed disaster responses can lead to significant economic downturns, the loss of critical infrastructure, and even socio-political unrest. In light of this, coupled with the increasing urbanization and economic diversification in Kuwait, understanding the nexus between organizational demographics and disaster management is not only a matter of academic interest but an urgent need for policy-making and strategic planning.

Recognizing this urgency, the Kuwaiti government has already made commendable strides. The establishment of a centralized and permanent apparatus for crisis management and response is an example of their proactive and comprehensive approach to disaster preparedness [

15]. This initiative not only emphasizes the critical role of effective disaster management but also underscores the importance of understanding the relationship between organizational characteristics and disaster management practices in the Kuwaiti context. Building upon prior research on Kuwait’s institutional preparedness [

16], the objective of this research is to delve deeper into the relationship between organizational characteristics and disaster management practices within the Kuwaiti context. By investigating this relationship, this study aims to identify how specific demographic attributes of organizations influence their capacity for effective disaster mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. Moreover, this research seeks to provide nuanced insights and recommendations that may enhance disaster resilience. Through this analysis, it is hoped that organizations not only in Kuwait but also in regions with similar challenges can bolster their disaster management efficacy and better safeguard their economic stability.

2. The Literature Review

Despite extensive research on the difficulties organizations encounter during disasters and crises and the associated concept of organizational resilience, significant research gaps persist. The impact of organizational demographic attributes—such as the type of organization, its geographical location, the sector in which it operates, and its size—on an organization’s susceptibility to disasters still presents a wide, rich area yet to be thoroughly explored. Additionally, the way these attributes influence an organization’s operations and supply chain practices and strategies for better disaster preparedness, response, and recovery warrants further investigation.

Considerable studies have explored the impact of the organizational type on disaster preparedness and response strategies. For instance, Chikoto et al. [

17] compared non-profit, private, and public organizations and found that non-profits adopted more mitigation and preparedness activities than private corporations, despite resource constraints, and that public organizations outperformed private ones. Similarly, Kim and Zakour [

18] examined non-profit Human Service Organizations and discovered that organizational size significantly influenced the disaster preparedness of such organizations. Additionally, Kaneberg et al. [

19] examined the role of defense organizations in crisis response, highlighting the significant role of organizational type in shaping response efforts. These findings suggest that organizational type can play a significant role in disaster management, warranting further investigation within the Kuwaiti context.

Geographical location and organizational size have been identified as significant factors influencing disaster management strategies. Kapucu et al. [

20] and Ming et al. [

21] underscored the unique challenges organizations face based on their location, emphasizing the need for customized disaster preparedness initiatives. On the other hand, studies by Ming et al. [

21] and Eggers [

22] highlighted the role of organizational size in disaster management, indicating that it can influence an organization’s preparedness and response capabilities. Given these findings, understanding how these factors shape disaster management practices within Kuwait’s unique geographical and organizational context is essential.

The operational and supply chain competence in disaster management practices significantly influences an organization’s ability to respond effectively to crises. Dwivedi et al. [

23] discussed how administrative conflict, political biases, professional growth, and insecurity could potentially affect operations and supply chain competence in disaster management. Similarly, Aryatwijuka et al. [

24] highlighted the positive relationship between managerial competencies and supply chain performance, suggesting that improved managerial skills lead to more effective supply chains in a humanitarian context. Aldhaheri and Ahmad [

25] also delved into this aspect, focusing on supply chain agility and its role in enhancing an organization’s response in a crisis situation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has served as a backdrop for exploring new variables in disaster management practices. Kaneberg et al. [

19] and López-Vizcarra et al. [

26] examined how violence and the pandemic influenced organizational response and resilience. The latter study, in particular, provides insights into how supply chain strategies, particularly risk management programs, can mitigate the impacts of external crises on organizational performance.

A few studies have shed light on the importance of intangible resources and organizational capabilities in enhancing supply chain performance during crises. Torgaloz et al. [

27] demonstrated the significant positive effect of an organizational learning culture (OLC) on supply chain collaboration (SCC) and how decentralization can enhance this relationship.

Tasnim et al. [

28] and George and Elrashid [

29] explored the significance of strategic supply chain drivers in disaster management practices, such as pricing, inventory management, transportation, information, and sourcing. Effective inventory management and demand forecasting practices were highlighted as crucial for enhancing supply chain competence in organizations.

In the context of Kuwait, limited studies have explored the impact of organizational characteristics on operational and supply chain competence in disaster management practices. One such study by Al-Enezi et al. [

30] examined the disaster recovery plan and business continuity of Kuwait government entities, providing a foundation for the current research.

Overall, this comprehensive literature review underscores the importance of considering organizational demographic characteristics in understanding operational and supply chain competence in disaster management practices. The findings provide a foundation for future empirical research and offer practical implications for organizations seeking to enhance their resilience and effectiveness in the face of crises. By recognizing the influence of organizational demographics, policymakers, and practitioners can develop targeted strategies and interventions to strengthen disaster preparedness, response, and recovery efforts across various organizational contexts.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

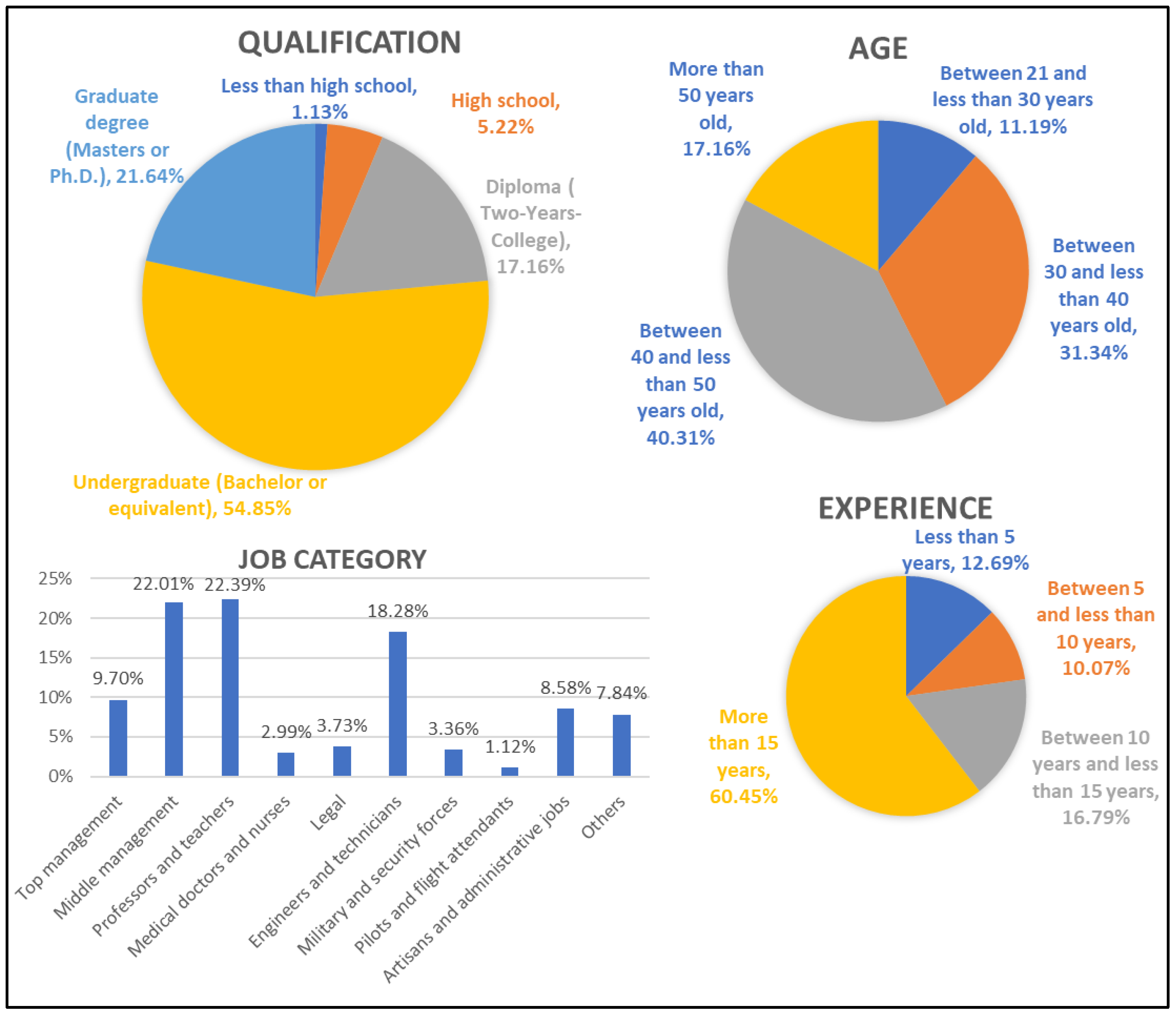

Before delving into the core findings of this study, it is essential to contextualize the data by understanding the demographics of both the participants and their affiliated organizations. These demographics serve as a foundational backdrop, illuminating the varied backgrounds, sectors, and experiences that shape this study’s outcomes. Spanning a vast spectrum of ages, educational qualifications, professional roles, organizational types, and years of experience, the participants and their organizations offer a comprehensive glimpse of perspectives within Kuwait. A more detailed breakdown is illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

The majority of the respondents were female, accounting for 52%, whereas males constituted 48%. These respondents reflected a variety of sectors and organizational types, encompassing governmental, private, and non-profit entities. Their backgrounds and work experience varied. Delving into educational qualifications, a prominent 54.85% of participants possess bachelor’s degrees. Additionally, a noteworthy 21.64% have attained graduate degrees.

In terms of age distribution, the most substantial segment of participants (40.3%) falls within the 40 to 50 age brackets. Close behind, 31.34% are aged between 30 and 40. The professional roles of participants are diverse; 22.39% function as educators or professors, roughly 22% occupy middle management roles within their institutions, and approximately 18% are engaged as engineers or technicians. Moreover, a segment of about 10% has secured top management positions. Notably, the vast majority, 60.45%, bring to the table an impressive tenure of over 15 years of work experience.

Figure 2 presents a comprehensive overview of the demographics and characteristics of the participating organizations. As detailed in the figure, a significant majority of the organizations, at 81.34%, are government entities. Most of these, amounting to 38.43%, are situated in Kuwait’s Capital district. When analyzing organization size by employee count, it is observed that a small fraction, at 14.93%, have fewer than 100 employees, while a notable portion, at 22.01%, have between 1000 and 4999 employees. Interestingly, the largest entities, making up 8.21%, boast a workforce of more than 20,000 individuals. Sector-wise, participants hail from a variety of industries. However, a prominent 31.34% are affiliated with Educational and Research institutions, making it the most represented sector in this study. This diverse data offer valuable insights into the wide range of organizations encompassed in this study, effectively setting the foundation for the ensuing analysis.

While the profiles of the participants and their organizations might not encompass a wholly representative cross-section of Kuwait’s entire workforce and organizational landscape, they do provide valuable insights by capturing diverse perspectives from different sectors and hierarchical levels within the country.

4.2. Inferential Analysis

Having established the demographic landscape of both the participants and their respective organizations, this study transitions its attention to the core of the analytical phase. Employing the previously described methods, including the chi-square test for independence and the One-way ANOVA test, the analysis explores the intricate relationships and impacts that organizational demographics (including type, location, sector, and size) exert on disaster management practices in Kuwait. Additionally, average scores for each question are computed. For Likert scale items, these scores range from 1 to 5, representing the collective sentiment of participants toward a specific question. Here, a score of 1 denotes “Strongly Disagree”, 2 signifies “Disagree”, 3 stands for “Uncertain”, 4 indicates “Agree”, and 5 corresponds to “Strongly Agree”. Therefore, an average score nearing 1 suggests strong disagreement, while one close to 5 implies strong agreement. For yes/no or checkbox-style items, the average score represents the percentage of participants in agreement. However, items not based on the Likert scale, or those with sub-answers not part of this analysis, do not have computed average scores. This thorough analysis encompasses all dimensions of the disaster management cycle, spanning from mitigation and preparedness to response and recovery.

Utilizing the chi-square test, this study examined possible associations between organizational demographics and the survey responses. Simultaneously, the ANOVA test helped determine if any significant differences existed in the mean scores of responses across various demographic groups. This methodological approach facilitated the identification of patterns and associations that could contribute to the development of more efficient and focused disaster management strategies.

In addition to these statistical analyses, this research also delved into participants’ evaluations of their respective organizations’ operations and supply chain management practices within the context of disaster management. This exploration included an assessment of resource sufficiency, personnel readiness, and infrastructure capabilities, all critical elements in successful disaster management implementation.

Table 1 presents the findings from the general questions section of the survey. The first question evaluates the perceived preparedness of organizations in managing disasters and crises within their operations and supply chains, with a specific focus on the sufficiency of resources, personnel, and infrastructure necessary for effective disaster management practices. Subsequent questions delve into the types of disasters employees believe their organizations are most vulnerable to, with responses categorized into different types of potential disasters. The

p-values of the findings, along with the average scores for each question, are outlined in

Table 1. The identified relationships were considered statistically significant at a 5% significance level.

The insights derived from

Table 1 emphasize that perceptions of an organization’s competence in disaster and crisis preparedness, specifically within operations and supply chain management, are influenced by diverse factors. These perceptions, when adequately understood and addressed, can pave the way for targeted interventions, ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently. Notably, organizational characteristics, such as type, location, and sector, significantly impact these perceptions, underscoring the necessity of considering each organization’s unique context when assessing disaster preparedness. In contrast, the size of an organization, measured by the number of employees, did not exhibit a significant impact on these perceptions. As a result, organizations in Kuwait, regardless of their size, might display varying confidence levels in their disaster management practices. This variance could be contingent on their type, location, and the sector in which they operate. For instance, a government institution might demonstrate greater assurance in its capacity to respond to a catastrophic event, while a non-profit organization, due to its different characteristics and perhaps resources, might feel less confident managing the same situation. Understanding these nuances aids in crafting bespoke disaster management strategies, promoting effectiveness, and ensuring that every organization is equipped based on its specific needs. This interpretation suggests that disaster management strategies might benefit from being tailored to an organization’s specific context rather than taking a one-size-fits-all approach.

Further analysis of the survey results reveals no statistically significant relationship between organizational characteristics, such as type, location, sector, or size, and perceptions of natural hazard threats. In other words, respondents’ perspectives regarding the threat from natural hazards were not significantly different regardless of their organization’s government, private, or non-profit status, its location within a specific district of Kuwait, the industry in which it operates, or its size. The absence of a significant relation between respondents’ perspectives on natural hazard threats and organizational characteristics could stem from various factors. Widespread education or awareness across Kuwait might lead to uniform perceptions of risk, overshadowing organizational variances. Other strong determinants not considered in this study might also influence perceptions. Additionally, cultural and societal norms could play a crucial role, or the actual risk from natural hazards might genuinely be uniform across the region. Delving deeper into the exact cause behind this absence could be the focus of further research.

Conversely, this analysis revealed significant relationships between certain types of man-made hazards, such as economic crises and industrial explosions, and organizational characteristics, including the industry in which an organization operates, as well as its location and size. The realization that certain sectors or locales might be more at risk for specific disasters underlines the necessity for those industries to adopt specialized preparedness measures. This implies that organizations in specific sectors may be more susceptible to and threatened by these types of disasters. Moreover, industrial pollution exhibited a significant relationship with an organization’s location and sector. This specific insight could be crucial for policymakers, prompting them to introduce or strengthen environmental regulations in areas most at risk. This observation suggests that organizations operating in particular industries or areas may be more vulnerable to this type of disaster. Lastly, the analysis determined that cyberattacks had a significant relationship with organizations’ size, as measured by the number of employees. This particular correlation suggests that larger organizations, which potentially handle more data, might be at a higher risk and thus may need to fortify their cybersecurity measures correspondingly.

Overall, this analysis highlights the importance of understanding the relationship between different organizational characteristics and the types of disasters they may be more susceptible to. By making these connections clearer, decision-makers can develop nuanced strategies, ensuring that preparedness measures are both proactive and reactive, thus maximizing their efficiency and effectiveness. In addition, this information can be used to inform disaster planning and preparedness efforts for organizations in different sectors and locations.

The ANOVA test outcomes, as detailed in

Table 2, echo the results of the prior chi-square test, underscoring a statistically significant difference at the 5% significance level in the mean scores of the survey questionnaire responses based on an organization’s type, location, and sector. These findings suggest that these specific demographic characteristics significantly influence the disaster management practices of Kuwaiti organizations. In practice, this signifies that interventions or changes aimed at improving disaster management might be more effective if they consider these specific organizational traits rather than a broad, generalized approach. In particular, the larger F-values for these organizational characteristics denote a more substantial between-group variability compared to within-group variability, highlighting the pronounced distinction in disaster management practices among organizations belonging to different types, locations, and sectors. Such pronounced differences can guide resource allocation, policy-making, and strategic planning in a direction that caters to each unique demographic characteristic.

However, as gauged by the approximate number of employees, an organization’s size failed to demonstrate any significant difference in the mean scores of the survey responses at the 5% significance level. This consistency across organizations of varying sizes indicates that size might not be a primary determinant in shaping disaster management practices. This could potentially lead to cost savings, as size-specific strategies may not be required.

Overall, the statistical analysis of the general questions suggests that certain organizational characteristics, such as type, location, and sector, play a pivotal role in shaping the effectiveness of disaster management practices among organizations in Kuwait. This raises the possibility that customized training programs, resources, and protocols based on these characteristics could enhance disaster readiness and response among the different types of organizations. However, the organization’s size does not appear to be a critical factor influencing disaster management effectiveness. Understanding this can help focus resources and training where they might have the most impact rather than spreading them thinly across organizations merely based on size. The subsequent sections will delve into the inferential analysis for each phase of the disaster management cycle in relation to respondents’ perceptions of their organization’s operations and supply chain practices.

4.3. Mitigation Phase

The chi-square test was deployed to probe potential associations between the mitigation phase’s items and the organizations’ demographic characteristics. The mitigation phase is critical as it involves strategies to reduce or eliminate risks before any disaster or crisis occurs. At a 5% significance level, the results revealed in

Table 3 indicate no significant relationships between the first four items of the mitigation phase and the demographic characteristics of respondents’ organizations. This finding suggests that regardless of their organizational demographic characteristics, respondents had broadly similar perceptions regarding their respective organizations’ efforts to mitigate the risks of disasters and crises. This shared perception across varied organizational backgrounds points to a potentially unified approach to disaster mitigation strategy. It emphasizes the foundational importance of mitigation across diverse entities. In other words, the organizations’ demographic factors, such as organization type, location, sector, and size, did not significantly impact organizations’ mitigation practices.

However, when examining the item about emergency tools (item 5) more closely, significant associations emerged. Certain tools and devices, such as ground communication lines, first aid kits, and anti-gas face masks, showed a significant relationship with the organization’s sector. Moreover, some tools, including radio devices, walkie-talkies, flashlights, anti-gas face masks, and the category termed “Others”, significantly correlated with an organization’s location. Lastly, organizational size, measured by the number of employees, significantly associated with particular tools, such as radio devices, flashlights, and anti-gas face masks.

In other words, the availability of specific emergency tools is linked with particular organizational characteristics. This insight is pivotal for disaster management stakeholders as they can tailor their mitigation strategies and tool provisioning based on these characteristics. For instance, organizations located in a specific area prone to communication disruptions might benefit from a higher allocation of radio devices or walkie-talkies. Still, no significant associations were found between the type of organization (government, private, or non-profit) and the emergency tools provided. This finding suggests that the type of organization does not substantially influence an organization’s mitigation practices related to the availability of emergency tools.

The presence of emergency tools varies across sectors. Understanding this variance can help industry regulators and policymakers formulate sector-specific guidelines or regulations. For instance, first aid kits are prevalent in the healthcare sector, and anti-gas face masks are mostly found in the oil sector. Location also affects the availability of these tools, possibly due to the correlation between an organization’s sector and its location. For example, organizations in the oil industry, where anti-gas face masks are commonly used, are typically located in the Ahmadi district in Kuwait. The size of an organization also seems to influence the emergency tools’ availability. In the case of the oil industry organizations in Kuwait, most are large, employing over 10,000 people. Consequently, anti-gas face masks are more likely to be found in these larger organizations.

These findings suggest potential disparities in disaster mitigation efforts across different sectors. This raises the question of whether all sectors are being provided with an equitable level of support and resources in their disaster mitigation practices. Equitable access to emergency tools is paramount to ensure comprehensive disaster readiness across the nation. It underscores the importance of ensuring that all organizations, regardless of industry or sector, have access to necessary emergency tools. Future initiatives or funding could be aimed at bridging these disparities and achieving more consistent disaster readiness levels across all sectors. It is important to note, however, that the data presented reflect employees’ perceptions of the presence of emergency tools, not the actual availability or accessibility of these tools. This could lead to a skewed or incomplete understanding of the real situation. Therefore, more research may be necessary to fully understand why certain emergency tools are more common in certain sectors. It may also be beneficial to validate these perceptions with actual inventories or audits of emergency tools across organizations. Regardless, these results highlight the importance of considering context when evaluating disaster mitigation and emergency tools provision.

The ANOVA test results, as displayed in

Table 4, highlight the significant impact of an organization’s geographic location on its disaster management mitigation efforts during the mitigation phase (

p = 0.013). This is an important revelation as it underscores that geography, more than other organizational characteristics, might determine the level of preparedness or the types of strategies employed. This significance suggests that an organization’s response during this phase can be shaped by unique environmental factors, potential risks associated with their specific locations in Kuwait, and local regulations. For instance, organizations situated near flood-prone areas might focus more on flood mitigation measures, while those in seismically active zones might prioritize earthquake readiness. The average survey scores were found to differ significantly across districts at a 5% significance level.

Contrarily, no other organizational characteristics—organization type, sector, or size—were found to have a statistically significant impact on the mean scores for the mitigation phase at the same 5% significance level. This suggests a potential universality in mitigation approaches across these dimensions, perhaps hinting at a shared understanding or standardization of practices irrespective of these characteristics. This indicates that these factors may not influence the effectiveness of an organization’s mitigation practices as much as their geographic location does.

These results underscore the crucial role of an organization’s geographic location in Kuwait when it comes to disaster management efforts during the mitigation phase. This insight has pivotal policy implications. Local governments might need to customize their support, resources, and guidelines based on the unique challenges of each geographic region. It points out that organizations in specific regions may prioritize certain mitigation practices based on their proximity to potential hazards and the local regulatory landscape. Further, it may be beneficial for organizations to collaborate and share best practices with others in their geographic vicinity to better address shared risks. Collaboration could take the form of joint training sessions, shared resources, or mutual aid agreements.

4.4. Preparedness Phase

The chi-square test of independence examined the potential associations between organizations’ demographic characteristics and disaster management preparedness items, including the presence of disaster and crisis preparedness plans, contingency plans, training programs, and strategies. At a 5% significance level, the findings presented in

Table 5 demonstrate significant relationships between the organization’s type (government, private, and non-profit) and several items related to disaster management preparedness. Notably, contingency plans (item 2), such as the “Fire plan”, were significantly associated with the organization’s type. This suggests that governmental, private, and non-profit organizations may prioritize different types of contingency plans based on their unique operations and risk profiles. For instance, government institutions, due to their public responsibility and a vast array of assets, may emphasize fire-related risks, while private entities, especially manufacturing units, may focus on machinery-related incidents. Non-profits, depending on their mandate, might prioritize human-centered risks, given their typical focus on service delivery. Similarly, the presence of a defined strategy for continuing operations during a crisis (item 4), including identifying critical processes, resources, and suppliers, was significantly related to the organization’s type. This might reflect the differing levels of resource availability, external dependencies, and organizational mandates across these sectors. Governmental organizations, for example, might have a higher threshold for maintaining operations during crises, given their public service mandate, while private entities might prioritize profitability and operational efficiency. Non-profits could focus on maintaining essential services, especially if they operate in the humanitarian sector. Again, this finding suggests that the resources and capacities to maintain operations during a crisis are affected by whether an organization is governmental, private, or non-profit.

Moreover, the type of training programs offered (item 6), specifically “Fire training drills”, was also significantly associated with the organization’s type. The emphasis on fire drills could vary based on the operational environments and the types of facilities these organizations manage. This finding indicates that organizations of different types may have varying priorities when it comes to training programs and highlights the need for tailored training programs specific to each organization’s needs and risks. From a policy perspective, it may imply the importance of facilitating cross-sector dialogues, where best practices and training modules are shared among different types of organizations. This way, knowledge from one sector can benefit another, leading to a more comprehensive and holistic approach to disaster management preparedness.

Furthermore, the results presented in

Table 5 indicate that an organization’s location, classified by the district, significantly impacts its disaster management preparedness efforts for specific items. In particular, the results suggest that an organization’s location significantly affects the items pertaining to operations and supply chain strategies (item 1). This item pertains to the presence of clear plans that establish relationships with multiple suppliers for critical products and services, maintain appropriate inventory levels, and implement contingency logistic plans.

The geographical location of an organization can determine the proximity to supply chains, major transportation routes, or ports, which play a critical role in sourcing and logistics. For instance, organizations closer to major ports might have diverse supplier relationships due to easier international trade accessibility, while those located inland might rely more on local or regional suppliers. The significance of this finding can be explained by the fact that an organization’s location may influence the availability and accessibility of suppliers, transportation, and logistics infrastructure, which, in turn, can affect the organization’s ability to prepare and respond to disasters effectively.

Additionally, the results reveal that an organization’s location significantly impacts its preparedness efforts related to the type of contingency plans and training programs offered (item 2 and item 6). Specifically, the item related to the “Toxic gas leakage and spread plan” was found to be significantly affected by an organization’s location. For example, districts that are industrial hubs might inherently be at a higher risk of toxic gas leakage due to the nature of the industries present. This finding is likely due to the varying levels of risk for toxic gas leaks across the different districts of Kuwait, necessitating different levels of preparedness.

Furthermore, the item related to “Chemical spill and gas leak drills” was also found to be significantly affected by an organization’s location. Organizations in areas with dense industrial activity or closer to chemical storage facilities might naturally prioritize these drills. This finding can be explained by the fact that organizations in certain locations may face higher risks of chemical spills or gas leaks, requiring more frequent or specialized training programs.

In light of these findings, policymakers and industry stakeholders should ensure that district-specific risks are adequately addressed in disaster preparedness frameworks. Tailoring strategies based on the unique characteristics and vulnerabilities of each district can lead to a more robust and effective disaster management approach. Additionally, these insights might prompt organizations to reassess their disaster preparedness strategies, ensuring that they are aligned with the unique risks posed by their geographic locations.

The results from

Table 5 shed light on the significant interplay between an organization’s sector and its disaster preparedness approaches during the preparedness phase. Specifically, the findings suggest that an organization’s sector significantly affects the items related to operations and supply chain strategies (item 1). This implies that respondents in different sectors feel differently about their organizations’ plans to ensure the availability of critical products and services, whether through multi-supplier agreements, appropriate inventory management, or contingency logistics planning.

A significant association was also found between the organization’s sector and the type of contingency plans it may have (item 2), as presented in

Table 5. In particular, the findings indicate that the sector type significantly impacts the presence of specific contingency plans, such as the “Toxic gas leakage and spread plan” and “Others”. For example, under the “Others” category, about 33% of respondents identified plans that were not mentioned in the questionnaire, such as “the art of dealing with people with neurological diseases”, “armed robbery plan”, “operational failure of computer systems”, and “hacking of consumer accounts and information”. This implies that organizations operating in different sectors may prioritize different types of contingency plans based on their unique risk profiles and vulnerabilities. For example, organizations in the petrochemical industry may place a higher priority on the “Toxic gas leakage and spread plan” compared to those in the healthcare or financial industries.

Additionally, the results presented in

Table 5 suggest that an organization’s sector significantly influences its strategy for continuing operations during a disaster (item 4). Specifically, the findings indicate that different sectors may vary in their perception of their organization’s capability to identify critical processes, resources, and suppliers to sustain operations during a crisis. This suggests that the sector in which an organization operates may influence its approach to continuity planning.

The results also reveal that the type of training programs an organization offers (item 6) is also significantly associated with its sector. This suggests that organizations operating in different sectors may require distinct disaster training programs tailored to their specific needs. Interestingly, the findings also show that respondents from organizations in different sectors did not hold the same perception about the provision of the “Helping people with special needs” drill. This may indicate varying levels of preparedness and sensitivity to the needs of vulnerable populations among organizations in different sectors.

When asked about their level of preparedness to face disastrous events while in the workplace (item 10), a significant association was observed between the organization’s sector and respondents’ answers. The findings suggest that the industry to which an organization belongs significantly impacts how respondents perceive their level of preparedness, indicating that the preparedness levels may vary based on the sector type. For instance, respondents from the healthcare industry may feel more prepared due to their experience in handling medical emergencies, while those from the financial sector may feel less prepared as they may not have had any prior training for such events.

The findings presented in

Table 5 also suggest that the organization’s sector type significantly impacts its preparedness plans’ “novelty” (item 11). Specifically, the results reveal that respondents from different sectors hold different perceptions about their organization’s disaster preparedness strategies and whether they have been developed or revised recently, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This could be due to the fact that certain sectors may have experienced more disruption or challenges during the pandemic, leading to heightened awareness and concern about preparedness measures. This finding highlights the importance of regularly reviewing and updating plans to address emerging threats and challenges.

Overall, these findings regarding the organization’s sector type imply that disaster preparedness plans and strategies should be tailored to each sector’s specific needs and characteristics to effectively manage and mitigate the impact of disasters and crises.

Lastly, the results reveal significant associations between the size of an organization, as measured by the number of employees, and various items related to the preparedness phase. Notably, the findings indicate that the size of an organization significantly impacts the existence of specific contingency plans (item 2), such as the “Fire plan”. This implies that larger organizations may be more likely to have more comprehensive contingency plans than smaller ones. The underlying rationale can be deduced: larger organizations typically possess more resources—financial, human, and technological. As such, they are better positioned to create and maintain comprehensive disaster management frameworks. This is not to say that smaller organizations do not recognize the importance of such plans, but they might face budgetary and resource constraints that hinder extensive planning.

Furthermore, the size of an organization was found to have a significant impact on the type of training programs it offers (item 6), as shown in

Table 5. Specifically, there was a significant association between the organization’s size and the offering of specific training programs related to disaster preparedness, such as “Chemical spill and gas leak drills” and “Dangerous and explosive material drills”. This implies that larger organizations may prioritize different training programs to ensure their employees are prepared for potential disasters and crises compared to smaller organizations. The focus on niche training programs, such as “Chemical spill and gas leak drills” and “Dangerous and explosive material drills”, hints at a proactive approach to tackle potential high-risk scenarios, especially prevalent in sectors such as the oil and petroleum industry. In contrast, smaller entities, perhaps due to budget limitations or lower risk profiles, might concentrate their resources on fundamental disaster response measures such as basic first aid.

The results presented in

Table 5 indicate that an organization’s size also significantly impacts the extent to which employees participate in training programs offered by their organization (item 7). The findings suggest that larger organizations may be more likely to have formal training programs and resources available to employees, which may increase participation rates. A broader implication of these findings is the pressing need for policy adjustments. Recognizing the discrepancies in disaster preparedness capabilities across organizations of different sizes, policymakers might need to consider more supportive measures for smaller entities. Additionally, larger organizations may have more resources to allocate to training and development, which could contribute to employees feeling more prepared and confident to respond to a disastrous event.

The ANOVA test was conducted to examine the differences in mean scores for variables related to the preparedness phase based on various organizational characteristics. The results presented in

Table 6 reveal significant differences in mean scores related to the preparedness phase based on the organization’s type, location, and sector at a 5% significance level.

The significant differences in mean scores for the preparedness phase based on organization type, location, and sector highlight the influence of these organizational characteristics on the evaluation of preparedness levels. For example, different types of organizations, such as governmental, private, and non-profit entities, may view preparedness through different lenses due to their inherent organizational goals and objectives. Varying resources, funding, and risk management strategies impact their perceived preparedness. The location of an organization can also play a role, as proximity to disaster-prone areas or access to infrastructure and support services can affect preparedness efforts. Additionally, the sector to which an organization belongs brings specific risks, regulations, and industry practices that shape preparedness evaluations. For instance, a healthcare organization might prioritize bioterrorism preparedness more than a financial institution would. Interestingly, this analysis did not reveal a significant difference in the preparedness phase based on the organization’s size, as suggested by the relatively small F-value and non-significant p-value, suggesting that combining factors beyond organizational size alone influences preparedness levels. Understanding these associations provides valuable insights for tailoring preparedness strategies and enhancing overall organizational resilience.

The F-values derived from the analysis indicate the variance ratio among groups to variance within groups. In the presented results, sector type has the largest F-value, signaling that it potentially exerts the strongest influence on preparedness levels among all the considered factors. The organization type and location also significantly influence the preparedness phase, albeit to a lesser extent, as indicated by their smaller but still significant F-values. Such observations emphasize the multifaceted nature of disaster preparedness and the confluence of several factors in determining an organization’s readiness level. These conclusions are further confirmed by the p-values associated with each of these factors, all of which are below 0.05, demonstrating that these differences are unlikely to have occurred by chance.

4.5. Response Phase

The chi-square test of independence in this phase was utilized to investigate the potential associations between organizations’ demographic characteristics and various disaster management response items. These items included the availability of disaster response teams, the implementation of early warning systems and communication strategies, as well as the ability to effectively notify stakeholders such as suppliers, transportation providers, emergency responders, and government agencies. The essence of analyzing these interconnections was to offer clarity on the dynamics between an organization’s demographic backdrop and its adeptness and strategies in reacting to calamities.

The results in

Table 7 revealed several significant associations at the 5% significance level. Notably, the organization’s type, location, and sector significantly impacted various aspects of disaster response. For example, the presence of a specialized disaster response team (item 1) was significantly associated with the organization’s type and sector. This finding suggests that the organization’s character, whether it is a government, private, or non-profit entity, and the industry in which it operates influence its capacity to form specialized disaster response teams. For instance, government organizations typically have greater access to resources and infrastructure, allowing them to allocate funds and personnel to specialized disaster response teams. Their mandate to ensure public safety and security may also drive the establishment of such teams as part of their emergency management efforts. In contrast, private organizations, especially large corporations, may have the financial means to invest in dedicated response teams as part of their risk management and business continuity strategies. Non-profit organizations, while potentially facing resource constraints, may collaborate with other organizations or rely on volunteers to form specialized response teams, leveraging partnerships to enhance their disaster response capabilities.

Regarding the association between sector type and the availability of disaster response teams, the nature and the scope of different sectors, which have distinct operational requirements, regulatory frameworks, and levels of exposure to specific types of disasters, may necessitate the establishment of specialized teams dedicated to handling disasters and crises. The diversity and uniqueness of each sector underscores the imperative of sector-specific response frameworks, emphasizing that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be effective in ensuring robust disaster management. For example, organizations operating in high-risk industries, such as healthcare, energy, or transportation, may require personnel with specialized disaster response skills. Furthermore, the organization’s sector can influence its resources, priorities, and regulatory requirements, shaping its disaster response capabilities. For example, sectors with stringent regulations and compliance standards, such as healthcare or financial services, may be more inclined to have specialized response teams as a result of industry-specific mandates or guidelines.

Additionally, the results reveal a significant association between organization size and the ability to form disaster response teams during emergencies (item 2). This suggests that larger organizations may have a greater capacity and resources to mobilize and assemble response teams promptly when faced with unexpected disasters. Forming disaster response teams quickly and effectively is crucial for mitigating the impacts of disasters and ensuring a coordinated response. It is worth noting the innate advantage that the scale of operations brings to large organizations, providing them with a broader margin to mobilize resources during crises. Larger organizations often have more extensive networks, personnel, and logistical capabilities, allowing them to respond swiftly to emerging crises. The availability of resources, such as personnel with diverse skill sets, communication systems, and designated response protocols, may contribute to their ability to form disaster response teams promptly. On the other hand, smaller organizations may face challenges in swiftly assembling response teams due to limited resources, including personnel, infrastructure, and funding. The agility and nimbleness of smaller organizations, while advantageous in some scenarios, might pose a challenge in disaster response where resource-heavy operations are imperative. These constraints may hinder their ability to establish dedicated teams specifically trained to handle emergencies. As a result, smaller organizations may rely on external support, such as partnerships with other entities or mutual aid agreements, to enhance their response capabilities during disasters.

Table 7 also demonstrates significant associations between specific organizational characteristics and the typical formation of disaster response teams (item 4). This underscores the nuanced approach organizations undertake in assembling their disaster response teams, influenced heavily by their intrinsic features and external environments. “Nomination” methods were significantly associated with the organization’s type, indicating varying team selection approaches across sectors. The “Based on seniority on the job” method exhibited associations with the organization’s type and location, potentially influenced by organizational culture and geographic factors. Understanding these associations can be paramount in anticipating the efficacy and agility of a disaster response team in varied contexts. The organization’s size correlated with the formation methods of “Based on connections” and “Voluntarily”. Larger organizations might rely on their broad networks for recruitment, while smaller ones might depend on voluntary participation due to resource constraints.

Sector type significantly influenced the decision autonomy of disaster response teams (item 5). Sectors with bureaucratic structures often demonstrate lower levels of decision autonomy, necessitating management involvement in disaster responses. This highlights the intricate balance between adherence to protocols and agility required in disaster management. Conversely, such sectors as healthcare lean toward decentralized decision-making, empowering their teams to act swiftly during crises. Such empowerment can be crucial in life-saving sectors where time-sensitive decisions could greatly affect outcomes.

Furthermore,

Table 7 provides insights into the significant association between the location of organizations in Kuwait and their ability to promptly and efficiently notify all stakeholders in the event of a disaster (item 6). This relationship between location and communication efficacy reveals the importance of strategic geographical positioning in disaster response strategies. The findings underscore the importance of location in determining the effectiveness of communication and coordination with key stakeholders during disastrous events. In Kuwait, the location of an organization plays a vital role in its proximity and accessibility to various stakeholders, including local suppliers, transportation providers, emergency responders, and government agencies. Organizations situated in different regions of Kuwait may encounter distinct challenges and opportunities when it comes to communication infrastructure, geographical proximity to stakeholders, and compliance with regulatory frameworks. This suggests that location-based contingency planning may be vital for organizations operating in different parts of the country. These factors can significantly impact their ability to establish robust communication channels and disseminate critical information promptly during a crisis. For instance, organizations located in urban areas such as Kuwait City may benefit from well-developed communication networks and rapid access to emergency services, enabling efficient notification and coordination with stakeholders. Conversely, organizations located in more remote areas or on the outskirts of Kuwait may face challenges in terms of connectivity and the availability of emergency response resources, which can impact their ability to promptly notify stakeholders during a disaster.

Furthermore, the analysis of

Table 7 reveals additional significant associations between the use of communication strategies and stakeholder notification efficiency (item 7) and the locations of organizations in Kuwait. Specifically, the utilization of “Text messages via mobile phones” as a communication strategy was found to be significantly associated with organizations’ locations. This implies that geographically dependent factors, such as network coverage or regional preferences in communication modes, may influence the reliance on certain communication tools. The findings suggest that the effectiveness of communication strategies may vary depending on the geographic location of organizations in Kuwait. Given the widespread adoption of mobile phone usage, leveraging text messages as a communication channel can be an efficient and widely accessible method to notify stakeholders during disasters or crises. This association highlights the importance of considering location-specific communication strategies to enhance stakeholder notification efficiency and ensure the timely dissemination of crucial information.

Regarding the maintenance of early warning systems (item 8), the analysis of

Table 7 revealed significant associations between this aspect and both the location and size of organizations. These findings shed light on the influence of organizational characteristics on the adequate upkeep of early warning systems in Kuwait. Understanding these associations may be critical for policymakers and business leaders to allocate resources or provide tailored support for organizations, ensuring that they are equipped with well-maintained early warning systems. The location of organizations plays a vital role in determining the accessibility and availability of resources required for maintaining early warning systems. Organizations in areas prone to specific types of disasters, such as coastal regions vulnerable to storms or seismic zones at risk of earthquakes, may prioritize the regular maintenance and calibration of their warning systems to ensure reliable and accurate alerts. It emphasizes the need for organizations in high-risk areas to undertake periodic assessments and invest in the best available technologies. Additionally, the proximity to relevant authorities and support networks in specific locations can facilitate collaboration and mutual assistance in maintaining and upgrading these systems. Moreover, the size of organizations can also impact their capacity to maintain early warning systems effectively. Larger organizations may have dedicated resources, such as dedicated personnel and specialized departments, to oversee the regular maintenance and monitoring of these systems. On the other hand, smaller organizations with limited resources may face financial constraints or expertise challenges, potentially affecting their ability to ensure the optimal functioning of early warning systems. Accordingly, such organizations may benefit from partnering with larger entities or seeking grants and technical assistance to potentially affect their ability to ensure the optimal functioning of early warning systems.

Moreover, the analysis of

Table 7 revealed a significant association between communication protocols by top management to their employees (item 10) and the sector type of organizations. This finding highlights the sector’s influence in shaping communication practices within organizations operating in Kuwait. These variations in communication protocols, as suggested by the analysis, underscore the importance of crafting communication strategies that align with the specific needs, challenges, and expectations of each sector. This means different sectors have distinct organizational structures, communication norms, and operational requirements. Therefore, the nature of the industry can influence the communication protocols adopted by top management to effectively convey crucial information to employees during times of crisis or calamity. For example, sectors prioritizing real-time information sharing and rapid decision-making, such as the technology or healthcare sectors, may employ direct and frequent communication channels, such as instant messaging platforms or regular meetings, to ensure timely and accurate dissemination of critical information. These sectors may also benefit from regular training sessions to ensure that employees are well-versed in using these communication tools and can respond effectively during emergencies. In contrast, sectors that operate in highly regulated environments or bureaucratic structures, such as government or financial sectors, may adhere to more formalized communication protocols involving official announcements, written directives, or cascading communication through hierarchical channels. Understanding and adapting to these sector-specific nuances in communication can lead to more effective crisis management and employee engagement during critical situations.

Furthermore, the analysis of

Table 7 unveiled significant associations between the type of communication strategies used by management with employees during disasters or crises (item 11) and various organizational characteristics. These findings shed light on the influence of organizational size, location, type, and sector on the choice of communication methods employed by management. This suggests that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to communication during disasters; instead, it is crucial to adapt strategies based on the unique attributes and needs of an organization. The selection of communication strategies is influenced by organizational factors encompassing the scale, context, and nature of operations. For example, larger organizations may rely on “Direct phone contact” to ensure immediate and personalized communication with employees across different departments or branches. On the other hand, organizations in diverse or geographically dispersed locations may utilize “walkie-talkies” to facilitate real-time communication and coordination. It is vital for organizations to understand their intrinsic attributes to select the most effective communication tools that can overcome potential barriers and address specific communication challenges inherent to their operational structure. In addition, the organizational type and sector can influence the choice of communication strategies. For instance, organizations operating in sectors with stringent regulations or compliance requirements, such as finance or healthcare, may prioritize using secure and traceable communication channels such as “E-mails”. The need for transparency, accountability, and documentation might drive these choices in such sectors. Meanwhile, organizations in sectors where information dissemination and public outreach are crucial, such as media or public relations, may heavily rely on their “Organization’s website” as a primary communication tool. This underlines the broader point that effective communication, especially during crises, requires an understanding of both the external factors related to industry norms and the internal factors stemming from organizational makeup.

Finally, the results reveal a significant relationship between the capacity to continue operations during a crisis, as measured by “Primary operations” (item 13), and the organization’s sector type. This finding emphasizes the impact of the organization’s industry on its disaster and crisis resilience and continuity. The resilience of an organization, defined by its ability to bounce back or maintain continuity in the face of disruptions, is intricately linked to the very nature of its business and its role in the broader ecosystem. Different sectors may exhibit varying levels of susceptibility and capacity to sustain their primary operations during challenging circumstances. For instance, organizations in industries characterized by critical infrastructure, such as energy or telecommunications, may prioritize the uninterrupted functioning of their primary operations to ensure the essential services they provide to society. The fallout from disruptions in these sectors can have widespread and cascading impacts on other sectors, communities, and even entire economies. On the other hand, organizations in sectors with more flexible or adaptable operations, such as technology or consulting, may have greater flexibility to adjust their primary operations during a crisis. This adaptability, often supported by digital infrastructure and the ability to operate remotely, can be a crucial factor in their resilience. While an organization may face different challenges, the capacity to pivot or modify its operational approach can be a decisive factor in ensuring continuity.

The ANOVA test was performed to examine differences in mean scores related to the response phase based on various organizational characteristics.

Table 8 presents the results, which indicate significant differences in mean scores for the response phase based on the organization’s type, location, and sector, with a significance level of 5%.

The organization type, be it governmental, private, or non-profit, instigates differences in resource allocation, decision-making strategies, and funding methods, thus influencing the ability of an organization to respond effectively. Additionally, the cultural and bureaucratic aspects inherent to each organization type can shape their agility and responsiveness during crises. The F-value of 3.423 for organization type suggests that the between-group variability is significantly larger than the within-group variability. Location plays a pivotal role in shaping an organization’s response capabilities. Elements, such as the distance from emergency services, the status of transportation infrastructure, and the reliability of communication networks, can directly influence response times and coordination. Moreover, geographical factors, including the terrain and vulnerability to specific natural hazards, may also dictate the manner and speed of response required. The F-value of 3.139 for the location implies a notable variance between different location groups. Moreover, the sector of operation also significantly affects an organization’s response capabilities. Sector-specific norms, regulations, and operational dynamics can either boost or restrict the ability to respond, as evidenced by an F-value of 2.731. It is crucial to note that sectors may also have varying levels of community and stakeholder expectations, further influencing their responsiveness. Interestingly, organization size was found to be not significant, with an F-value of 1.451. This reveals that factors beyond the organization’s size contribute more significantly to response capabilities.

These findings offer critical insights into how disaster response initiatives can be improved. For instance, organizations in certain sectors or locations can focus on mitigating their unique challenges, while all organization types could examine internal policy and strategy adjustments to bolster their disaster response effectiveness. Understanding the unique intricacies and nuances tied to each characteristic can inform tailored interventions and initiatives. These results underline the value of a targeted, organization-specific approach in improving disaster response capacities, thus fostering greater societal resilience.

4.6. Recovery Phase

The chi-square test of independence was performed to investigate the relationships between organizations’ demographic characteristics and key factors related to the recovery phase in the disaster management cycle. This analysis examined various aspects of the recovery phase, including the coordination among different stakeholders, such as government agencies, non-governmental organizations, private sector entities, and communities, aiming to facilitate a smooth and effective recovery process. Additionally, this study explored the time required for organizations to resume their operations following disasters, the presence of supportive laws and regulations to assist affected employees, and the existence of well-defined procedures for reconstructing damaged infrastructure.

The findings from

Table 9 indicate significant associations between the availability of strategies to enable organizations to resume operations after disasters (item 1) and the sector type of organizations at a 5% significance level. This suggests that the sector in which organizations operate in Kuwait plays a crucial role in determining their recovery capabilities following disasters or crises. The strategies organizations employ to resume operations, such as coordination with stakeholders, resource allocation, and adaptation of business processes, may vary depending on the nature of the sector. Healthcare and oil industries, for instance, may prioritize rapid recovery and have well-defined strategies in place to ensure the continuity of operations and essential services. Alternatively, sectors less directly impacted by disasters, such as professional services such as law firms, may have greater flexibility in resuming operations and adapting to changes in the surrounding environment. Building on this, the implications of these findings suggest that policymakers and industry leaders should consider sector-specific nuances when designing recovery protocols. Tailored strategies might ensure more efficient recovery and a quicker return to operational normalcy for organizations. This finding emphasizes the importance of sector-specific disaster management and recovery planning approaches.

Results also indicate a significant association between the organization’s size and the ability to recommence primary operations following a disaster. Understanding this relationship can inform post-disaster recovery plans and decision-making processes that seek to improve recovery efforts. For example, larger organizations may have distinct advantages when resuming primary operations following a catastrophe. They often have more resources, financial capacities, and personnel, which can contribute to a more robust and expeditious recovery process. The statistical interpretation of this relationship suggests that larger organizations might inherently possess a more resilient infrastructure, making them better equipped for quick disaster responses. In addition, larger organizations may be able to assign dedicated teams, invest in sophisticated technologies, and mobilize resources more effectively to restore critical operations. On the other hand, smaller organizations may encounter unique challenges in the aftermath of a disaster. Limited resources, financial restrictions, and a reduced workforce may hinder their ability to resume primary operations quickly. It is vital to note that while these challenges might seem daunting, smaller organizations often display remarkable agility, turning their size into an asset for certain recovery strategies. Smaller organizations may require external support, stakeholder collaboration, and strategic decision-making to navigate the recovery process effectively. This finding highlights the importance of recognizing the diverse needs and challenges faced by organizations of different sizes during the recovery phase, emphasizing the need for tailored strategies that are both data-informed and cognizant of these disparities.

The chi-square results further reveal significant associations between the availability of supportive laws and regulations within organizations to assist affected employees (item 4) and several organizational factors. Notably, the associations between “Provide loans” and “Provide food supplies” with organization location suggest that the presence of these support measures may vary based on the specific geographical context within Kuwait. Furthermore, the significant associations observed between the “Temporary housing program” and the organization’s location, sector, and size suggest that the provision of temporary housing support is contingent upon geographical, industry-specific, and organizational capacity considerations. These findings could be attributed to several factors contributing to the significant associations observed between the type of supportive laws and regulations available in organizations and their location, sector, and size. These factors include government policies, industry-specific considerations, organizational culture and values, financial capacity, and stakeholder collaboration. Government policies related to disaster management, funding allocations, and policy frameworks can influence the presence of supportive measures. Different sectors may have unique support requirements based on the nature of their operations. Organizational culture and values can shape the approach to employee support. Financial capacity can impact the implementation of supportive measures, with larger organizations or those in sectors with higher resources having more capabilities. Collaboration with stakeholders can also affect the availability of support programs. Considering these factors is crucial for developing tailored approaches to employee support in Kuwait.

Finally, the recovery phase plays a vital role in restoring normalcy and rebuilding affected areas.

Table 9 highlights a significant association between the availability of quick procedures for reconstructing buildings and infrastructure after disasters or crises (item 5) and the location and sector type of organizations. Apparently, the geographical location of organizations in Kuwait can influence the availability of resources, logistical considerations, and coordination with relevant stakeholders during the reconstruction process. This infers spatial factors, such as proximity to raw materials or disaster severity across regions, play an indispensable role in shaping reconstruction strategies. Additionally, different sectors may have specific expertise and resources that contribute to the efficiency of reconstruction efforts. For instance, sectors with a pronounced construction or engineering focus might naturally be more adept at leading swift infrastructure rebuilds, underscoring the need for inter-sector collaborations during recovery.

The ANOVA test was employed to assess variations in the mean scores relating to the recovery phase across different organizational characteristics. The results, presented in

Table 10, reveal significant differences in the mean scores of recovery-related variables based on the organization’s location and sector type, with a significance level of 5%.

The F-values for the organization’s location (3.36) and the sector type (2.679) exceed the critical F-value for significance at a 5% level. These significant F-values indicate that the variances in the mean scores between groups (organizations in different locations and sectors) are more substantial than would be expected due to chance, suggesting real differences in their recovery phase capabilities.

For the location, the significant differences suggest that geographical factors, such as the type and frequency of disasters faced, as well as the available local resources and infrastructures, greatly influence an organization’s recovery capabilities. This implies that policy- and decision-makers might need to channel more resources and attention to specific regions, enhancing their recovery infrastructure. Organizations situated in disaster-prone areas might have developed stronger recovery measures due to necessity, leading to higher mean scores in this phase.

The sector type also shows significant differences, underscoring the diverse needs and strategies among different sectors during the recovery phase. Organizations in the healthcare and energy sectors, where continuous service is crucial, may have more robust recovery plans in place compared to other sectors where service interruption is less critical. This observation raises a pertinent point about sector-based collaborations: the organizations can potentially learn and adopt best practices from sectors that have demonstrated superior resilience and recovery capabilities.

Though organization type and size did not show significant differences in the recovery phase mean scores (F-values of 2.753 and 1.69, respectively), this does not necessarily imply they are irrelevant. Their influence might be subtler or interwoven with other factors that were not part of this study. It emphasizes that other factors, such as location and sector type, may have stronger impacts on the recovery phase.

These findings underscore the need to consider organizational characteristics, such as location and sector type, in planning and implementing disaster recovery measures. Tailoring recovery strategies to the unique circumstances of each organization could potentially improve their effectiveness and, consequently, the organization’s resilience to disasters.

5. Discussion

This section will provide a detailed interpretation of the findings, highlighting the implications of the results for organizations in Kuwait and their disaster management practices. The impact of demographic characteristics on each phase of the disaster management cycle will be discussed.

In the exploration of Kuwait’s landscape, a salient observation emerged: different types of organizations, be it in oil and gas, healthcare, education, or finance, operate within unique regional contexts that deeply shape their disaster management strategies. This intricacy of organizational types and their contexts bears similarities with findings from other research landscapes. For example, the complexity of cross-regional emergency cooperation captures the diverse interactions among varied governmental levels, mirroring the intricate organizational interactions we’ve observed in Kuwait. Likewise, studies from the United Nations disaster risk reduction efforts and those focused on Japan’s local public entities further validate the pivotal role of regional and organizational contexts. The consistent thread running through these studies buttresses the assertion that the nature of the organization and its contextual backdrop are intrinsically linked in determining disaster management strategies [

31,

32,

33]. Considering the country’s vulnerability to diverse hazards, including natural, man-made, and geopolitical events, organizations must exude confidence in their crisis and disaster management capabilities. A study highlighting the role of trust in disaster resilience reveals that trust, bridging citizens, institutions, and experts, is instrumental in shaping perceptions of risk and response. Although centered on community dynamics, the findings are relevant for the organizations. Trust determines an organization’s disaster management efficiency and resilience. The broader institutional environment, influenced by regional contexts, can amplify or erode this trust, thus impacting organizational preparedness and response [

34]. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the factors that contribute to varying levels of preparedness and confidence among organizations in Kuwait is essential to inform the development of targeted and effective disaster management strategies. Overall, the results imply that a one-size-fits-all approach to crisis preparedness may not be effective, and tailored strategies may be necessary to meet the unique needs and challenges of organizations from diverse backgrounds and contexts. This stance is echoed in a study from Milwaukee, which also underscored the importance of tailored strategies for different community and organizational contexts, resonating with insights from the broader international disaster management literature [

35].