1. Introduction

The relentless expansion of urban environments and the transformation of pristine landscapes into human-centric structures present a profound challenge to wildlife species [

1]. Among the various organisms grappling with the realities of urbanization, one avian species, the barn swallow (

Hirundo rustica), offers compelling insights into how animals adapt to these emerging habitats. Renowned for their extensive geographic range and unique nesting practices, barn swallows demonstrate remarkable resilience in the face of human-induced environmental changes [

2,

3].

One key facet of this resilience is the genial rapport barn swallows share with humans, which is especially visible in their nesting practices. Frequently, these birds erect their nests in close proximity to human dwellings, underscoring their ability to not just survive, but also thrive within urban ecosystems. However, urban sprawl poses a significant challenge to this adaptive species, primarily due to the erosion of natural landscapes and the resulting scarcity of optimal nesting sites. This deficit can impede the barn swallows’ reproductive success, potentially leading to decreases in their population numbers [

4].

Nest construction in barn swallows represents a unique blend of engineering prowess and adaptive behavior [

5]. With keen attention to detail, they gather mud pellets to build cup-shaped nests, which are then secured onto human-made structures such as barns, bridges, and homes. This careful selection of nesting sites is not an arbitrary choice; it embodies a well-honed survival strategy developed over countless generations. However, constructing these nests demands a considerable investment of time, energy, and resources, thus underscoring the pivotal role these nests play in the lifecycle of barn swallows [

6].

The design and dimensions of these nests are not only dictated by the availability and accessibility of building materials, primarily clay-laden mud [

7], but also by the parent swallows’ preferences for specific nesting locations and conditions. Swallows often select locations that offer both security from predators and favorable environmental conditions. Larger nests, meticulously molded with significant effort, offer ample space for incubation and the rearing of chicks, thereby enhancing their chances of survival [

8]. These nests allow parent swallows to nurture more offspring and shield them from potential predators, emphasizing a direct correlation between nest size, reproductive success, and overall population health. Furthermore, the parent swallows display a preference for constructing these larger nests in places that offer protection against weather-related challenges such as wind and rain [

9].

Despite these adaptive behaviors, the urbanization process, particularly the replacement of natural landscapes with concrete edifices, poses significant challenges to barn swallows’ traditional nesting practices. The scarcity of organic materials for nest construction forces these birds to travel greater distances in search of suitable materials, placing a considerable energy and time burden on them [

10].

The quality of the chosen materials plays a crucial role in determining the nest’s durability and size. Barn swallows show a preference for moldable materials that retain their shape when damp, such as mud with high clay content. These materials offer the required structural integrity to the nests, enabling them to withstand the weight of the eggs and chicks. To add to the nest’s comfort, barn swallows incorporate soft materials, like feathers, for insulation and cushioning, which is vital for the wellbeing of their eggs and chicks [

11].

Urbanization may lead barn swallows to deviate from their traditional nesting habits due to the scarcity of preferred resources. As a result, they might resort to using less than ideal materials or modify their nest structure, potentially leading to smaller and less durable nests [

12].

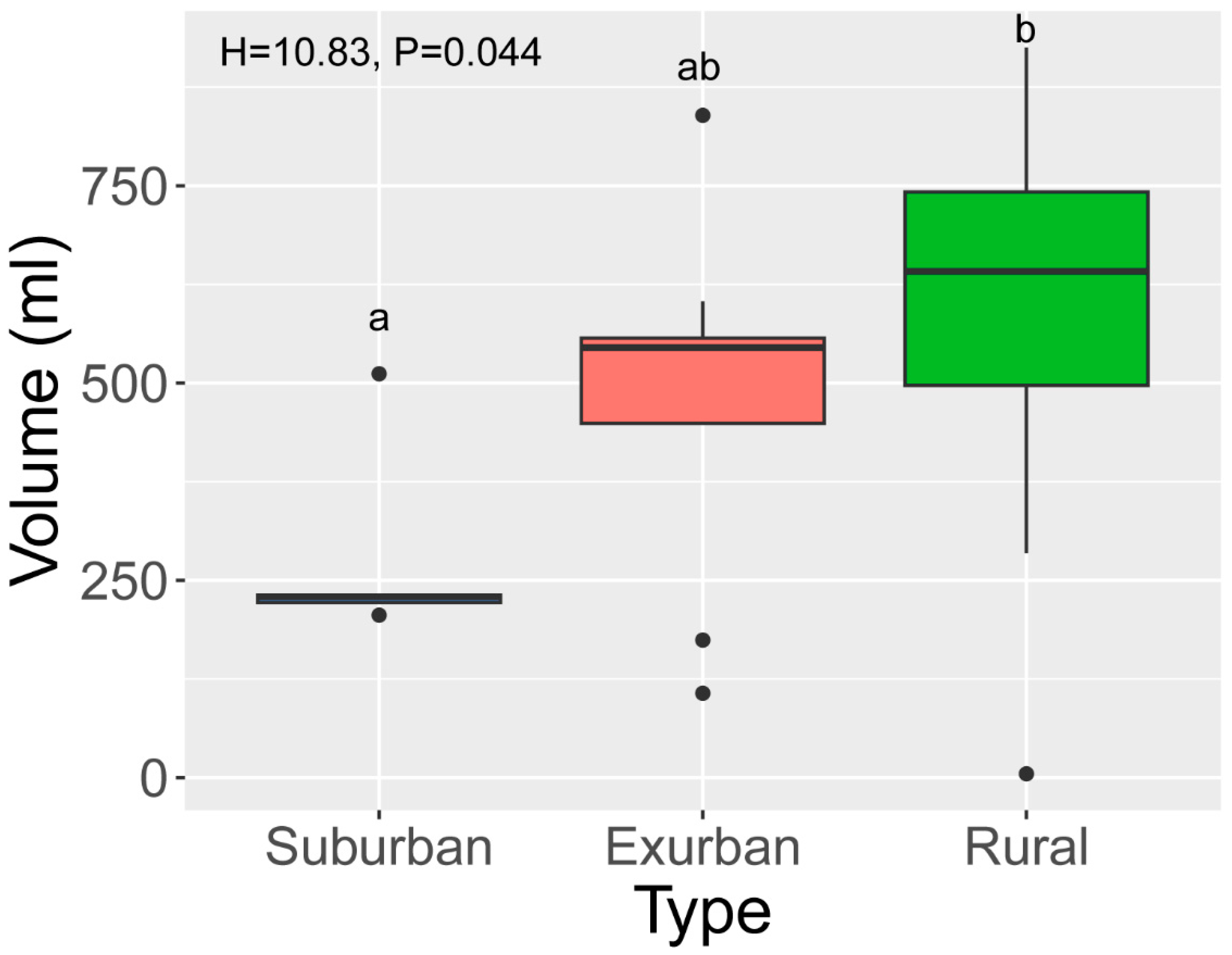

Our research aims to delve into the impact of urbanization on barn swallow nest size in South Korea, a country experiencing rapid urban growth. We focus on evaluating nest sizes in suburban, exurban, and rural regions, identifying any variations across these different environments. We also aim to examine the materials used in nest construction across these settings, anticipating potential variations.

Previous research has highlighted a negative relationship between urbanization and barn swallow nesting behavior [

10]. Therefore, we hypothesize that nest sizes for barn swallows in suburban and exurban locations could be smaller compared to those in rural areas. This decrease in size might be attributed to the limited availability of nesting materials in urban environments, compelling the swallows to fly longer distances in search of suitable materials or use lower-quality materials, leading to smaller and less durable nests. Our study’s insights could prove invaluable in understanding the full implications of urbanization on wildlife species and in devising effective conservation strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Sites

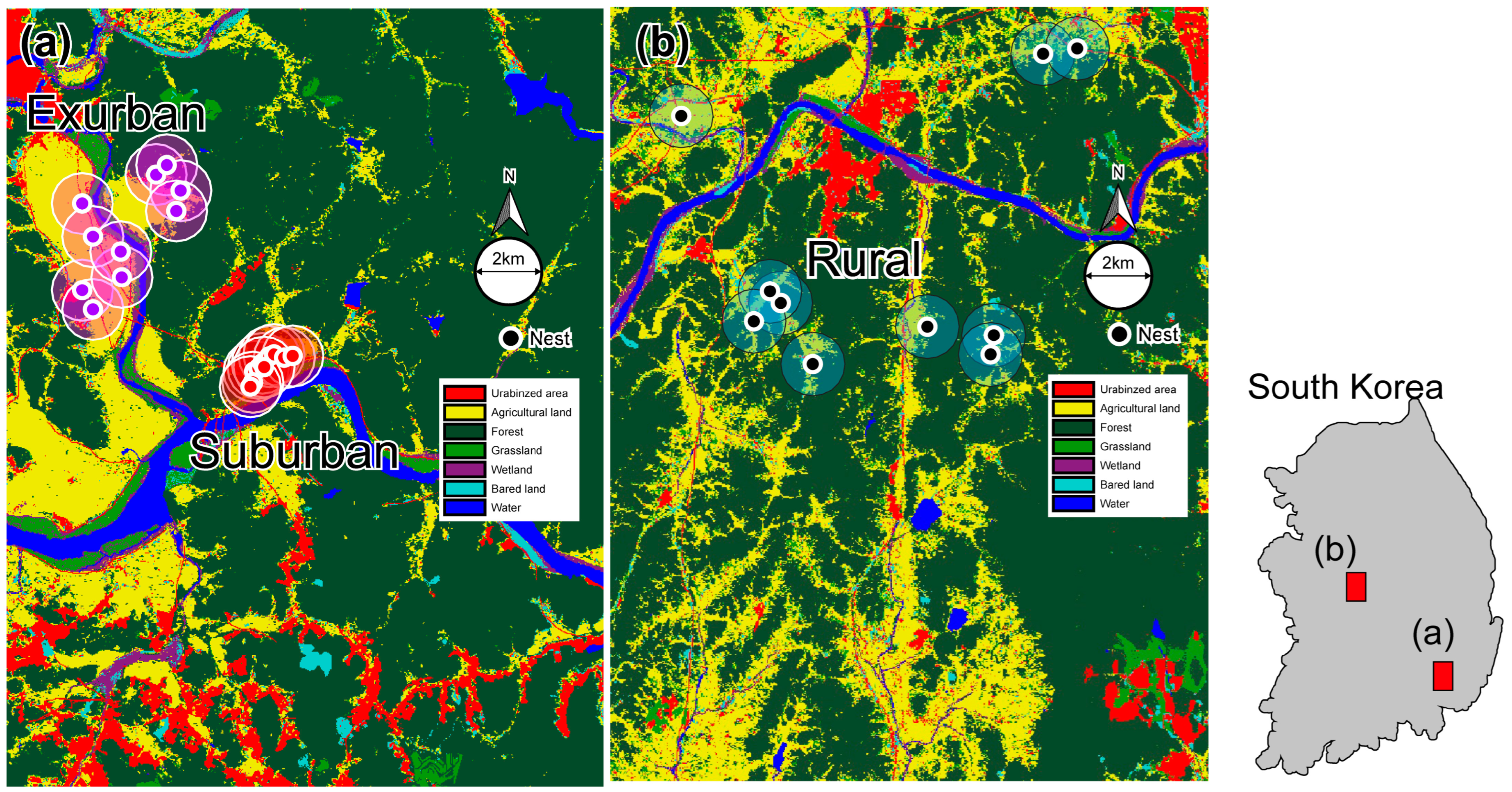

The research was conducted on barn swallow nests situated across three distinct types of areas: suburban, located in Gongju-si, Chungcheongnam-do; exurban, located in Gyeongnam-si and Milyang-si; and rural, located solely in Gyeongnam-si. In each area, a sample size of 10 to 13 swallow nests was selected for the investigation. The external volumes of these nests were meticulously measured using precise digital calipers, ensuring consistent and accurate data collection.

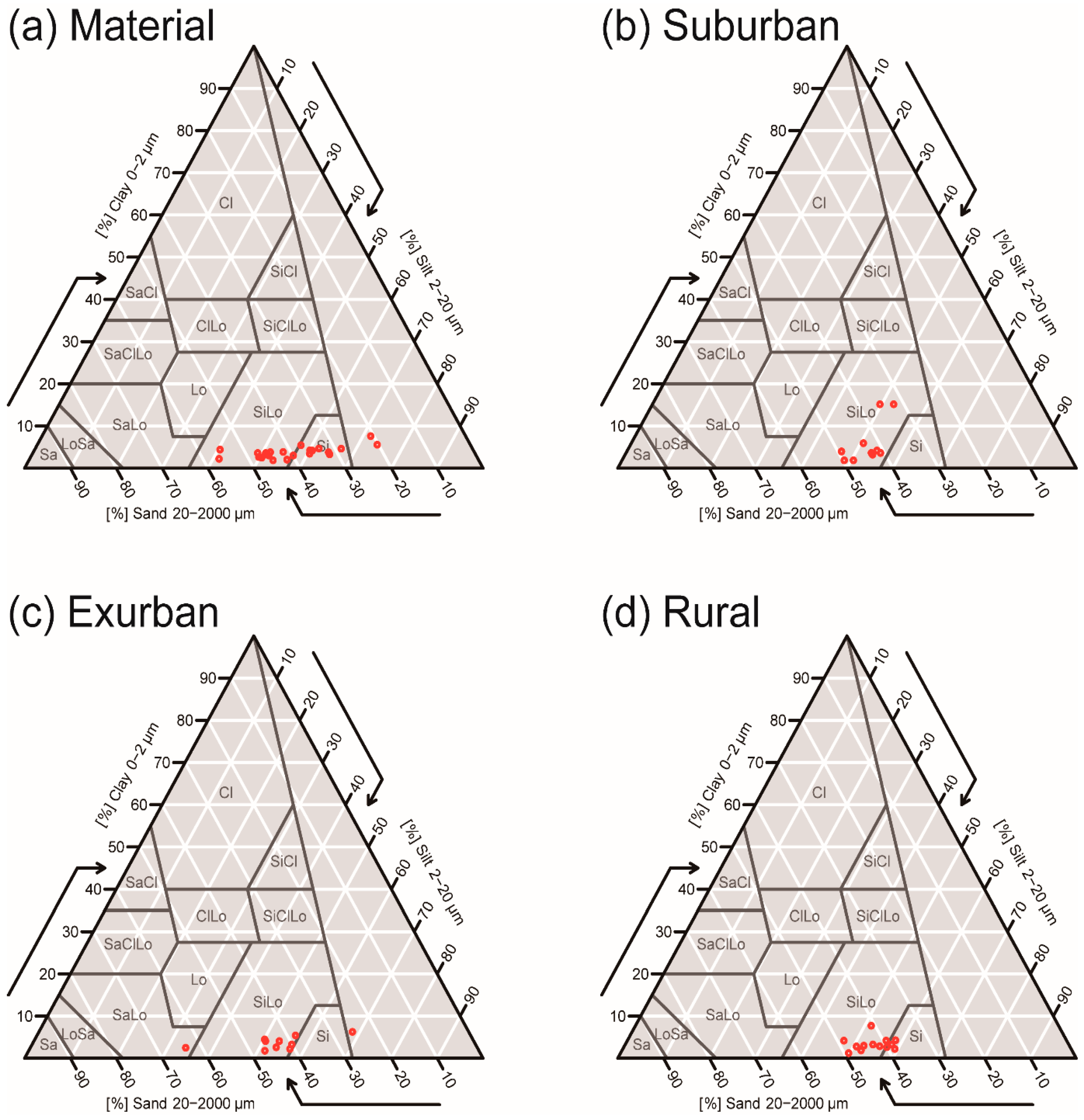

Furthering our analysis, portions of these nests were carefully gathered, prioritizing the preservation of their structural integrity, and subsequently used for thorough soil texture analysis. This was carried out with the objective of uncovering the key components that barn swallows employ for nest construction, thereby elucidating their nesting behavior within different urban gradients.

In addition, soil samples were procured from diverse land use types proximate to the nest locations, including paddy fields, riverine areas, woodlands, and dry fields. These samples were analyzed to understand the influence of local soil composition on the selection of nest-building materials by the barn swallows.

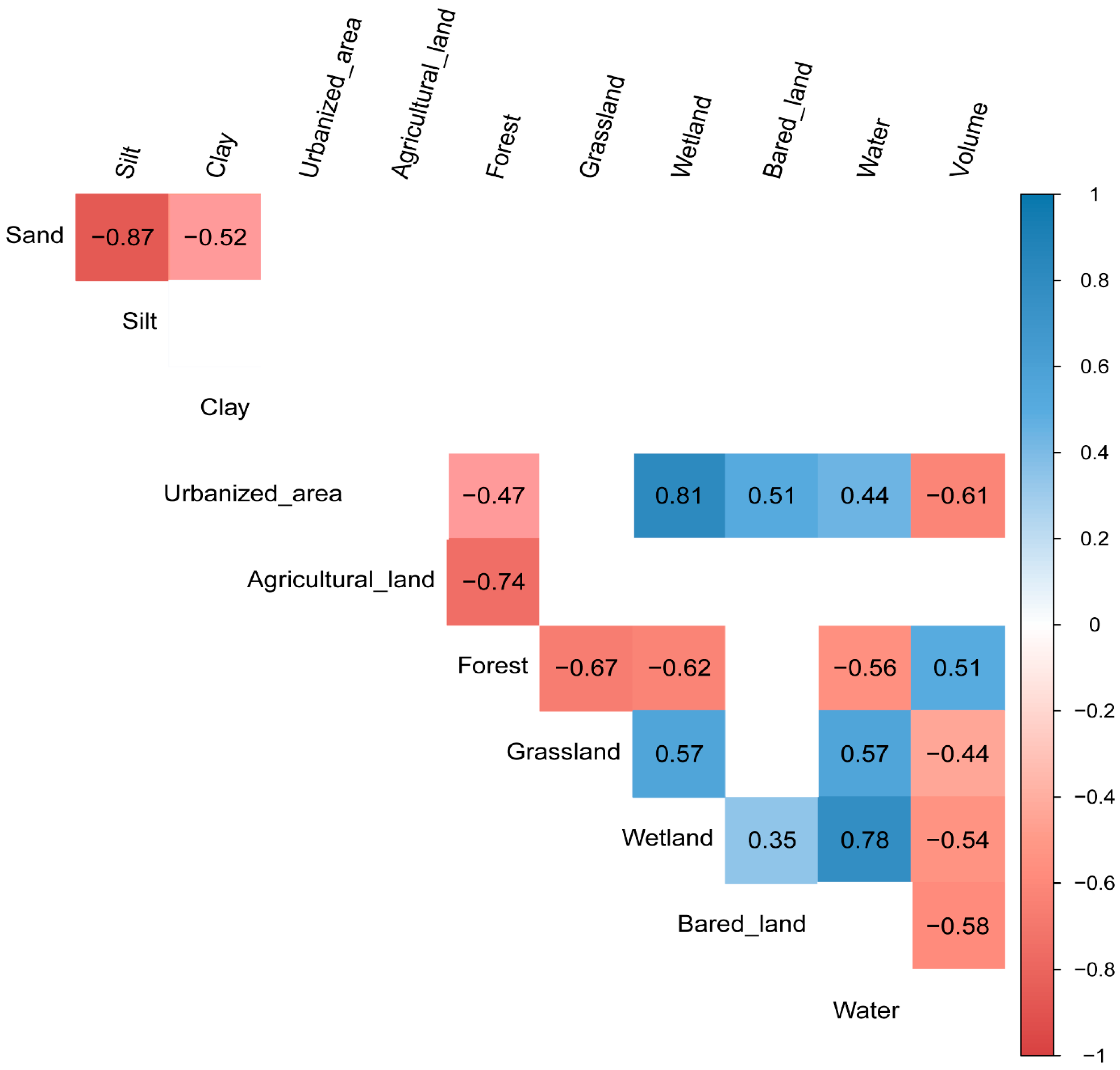

For the spatial analysis, we employed QGIS software (version 3.28) to compute the proportions of different land cover types within a one-kilometer radius surrounding the selected nest locations based on land cover map provided by the South Korean Ministry of Environment.

2.2. Nest Size Measurement

The measurement of the external volume of barn swallow nests was conducted using a high-precision 3D laser scanner, the Leica ScanStation P50 model, which has a precision level of up to 0.6 mm at 50 m. This instrument was selected due to its ability to create intricate three-dimensional depictions of the nests, thereby enabling the precise calculation of the nests’ external volume. In our study area, nests were identified and labeled, and the Leica ScanStation P50 was carefully positioned to garner a comprehensive 360-degree capture of each nest, ensuring all details were accurately depicted. The scanner operates by emitting fast laser pulses that reflect back from the object of interest, generating a point cloud, which subsequently forms a highly detailed 3D representation of the object.

Following this, we processed the 3D point cloud images using the Leica Cyclone, a sophisticated point cloud processing software. The software facilitated the translation of the 3D images into concrete volumetric measurements of the nests. To ensure precision and reproducibility, each nest was scanned thrice, and the average of these three measurements was used to calculate nest volume, thereby mitigating the potential impact of outliers or measurement errors.

We examined variations in barn swallow nest sizes across suburban, exurban, and rural areas using statistical analysis. Initially, we applied a Kruskal–Wallis test, suitable for multiple-group non-normal comparisons. Post-analysis was performed using Dunn’s test, which included a Bonferroni correction (α = 0.05) to regulate Type I error in multiple comparisons, thereby reducing false positives and increasing result validity. R software (version 4.2.2) was utilized for all statistical analyses.

2.3. Soil Texture Analysis

In compliance with established soil sampling protocols, we gathered soil samples from locations near the barn swallow nests using stainless steel sampling tools. Each soil sample weighed approximately 500 g. In each of the selected areas, three soil samples were collected, making a total of three replicates per area. These tools are renowned for their durability and lack of chemical interaction with the soil. To ensure uniformity and mitigate potential errors, all samples were collected at a consistent depth of 10–20 cm, a range typically characterized by soil organic matter and root activity.

Following collection, soil samples were air-dried to eliminate excess moisture which could potentially influence the subsequent analysis. Samples were then sieved to remove any large debris or extraneous matter. Utmost care was taken to store the soil samples in a cool, dry environment until analysis to prevent alterations in soil properties due to microbial activity or moisture absorption.

The soil texture of the samples was determined using a laser diffraction particle size analyzer (SALD-2300). This device functions by transmitting a laser beam through a sample and measuring the degree of scattering by individual particles in the sample.

The soil texture of samples from the nests and surrounding environment was classified using the soiltexture package in R, following the USDA soil texture classification system [

13]. Two clustering methods, k-means and hierarchical clustering with Ward’s method, were used to categorize the soil samples based on texture into sand, clay, or silt. To explore the potential correlation between the external volume of the barn swallow nests and the ratio of soil textures (sand, clay, and silt), the Pearson correlation coefficient method was employed. This statistic was utilized to gauge the strength and direction of the relationship between these variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software.

4. Discussion

The results of our research affirm the conjecture that urbanization bears a marked, negative impact on barn swallow nesting practices, with the manifested consequence being the construction of smaller nests. The observed decrement in the overall dimensions of nests in urban areas might be influenced by various factors. One potential aspect to consider is the quality and suitability of nesting locations in dense urban settings, rather than just the availability of space [

10]. Our study conducted across different land-use types—suburban, exurban, and rural—unveiled considerable variations in the external volumes of barn swallow nests. Nests positioned in rural areas presented significantly larger dimensions, as opposed to their urban counterparts.

The transformative effects of urbanization introduce a stark disparity. The transition from natural landscapes into concrete jungles due to uncurbed urbanization is observed to precipitate a significant reduction in the dimensions of barn swallow nests. In urbanized areas, barn swallows may encounter a different range of nest-building materials, which could lead them to use alternative or non-traditional resources. However, our study did not find significant differences in material composition across landscapes. These materials might not possess the same quality or characteristics as their natural counterparts, potentially leading to the creation of smaller, less durable nests [

14].

Furthermore, human activities can exert a direct impact on barn swallow nests. Damage inflicted by construction activities, deliberate destruction, or indirect effects such as noise and disturbances can lead to nest abandonment. Abandoned nests often necessitate swift rebuilding, which inevitably results in smaller nests due to constraints on time and resources. Urban development can drastically transform or completely obliterate natural habitats, thereby posing a formidable challenge for barn swallows in their quest for suitable nesting sites [

9]. A critical aspect that remains unexplored in our study is the potential influence of urbanization on the clutch size and body size of barn swallows. In alignment with our observation that urban nests are smaller, there may be physiological and behavioral implications for barn swallows that reside in urban areas. Previous studies in different avian species have indicated that birds in more urbanized environments tend to be smaller in size, potentially as a response to the unique challenges posed by urban landscapes [

15,

16]. If barn swallows in urban areas are smaller, this might be an adaptive response to the limited space available for nesting. Smaller body sizes could potentially also affect clutch size, given that body size in birds is often positively correlated with clutch size.

Beyond the influence of land use on nest dimensions, our research delved into the specifics of the materials employed in nest construction, uncovering barn swallows’ predilection for certain soil textures in nest-building [

17]. While the composition of materials used by barn swallows for their nests can show geographical variations based on their availability, our study indicates a discernible preference for silt loam and silt among these birds. The selection of these soil textures, especially silt loam, could be attributed to their ideal mix of particle sizes that afford the right balance of structural rigidity, moisture retention, and malleability for nest construction [

18].

However, it is important to emphasize that barn swallows demonstrate commendable adaptability and ingenuity in their nest-building strategies. Despite their preference for silt loam and silt, barn swallows exhibit significant flexibility in their choice of materials, adapting their selection based on the availability in their local environment. It is not uncommon to encounter barn swallow nests constructed from an array of materials, encompassing mud, plant materials, and feathers [

19]. Silt, while not as structurally robust as silt loam, remains a viable option for nest construction due to its ubiquitous presence near waterways and its suitability to be compacted into a durable nest structure. Comprised predominantly of silt particles with minimal quantities of sand or clay, silt continues to be a favored choice, especially in scenarios where the preferred silt loam is unavailable [

19]. The selection of nesting materials is not a mere choice of preference but a strategic decision that can have significant implications for a barn swallow’s reproductive success. The type and quality of materials used can directly impact the nest’s size, durability, and even its insulation properties, all of which affect the safety and survival of the offspring [

11].

Our study highlights the trend of smaller nests in urban landscapes. However, it is crucial to consider that variables like environmental conditions, predator abundance, and climate, among others, might also play roles in this observation [

17]. As such, the presence of preferred soil textures and other nesting materials in rural areas is not an absolute guarantee for larger nest construction. Further research exploring these additional variables is necessary to deepen our understanding of this complex ecological phenomenon.

One key observation from our research is the trend of smaller barn swallow nest sizes in urban settings. While urbanization might play a role, it is essential to approach this finding in the context of various factors that could influence nest size [

19]. While we observed a trend of smaller nests in urban landscapes, the potential implications on barn swallow breeding success and population dynamics warrant further research. The existing literature suggests possible detrimental effects of smaller nests, but direct connections to our observations require a more detailed investigation. Smaller nests constrict the available space for eggs and chicks, potentially leading to higher chick mortality rates due to less efficient brooding [

18]. Additionally, smaller nests might not provide sufficient protection against extreme weather conditions and parasitic infestations, which could increase egg and chick mortality rates [

19,

20,

21]. Furthermore, human disturbance remains a significant concern. Continuous interaction with humans and human-led activities, like construction, can create stress for barn swallows and directly impact their nests [

22]. This could escalate to the point of causing population disruption or even eradication [

10].

The significant transformations brought about by urbanization can influence bird behavior, specifically altering barn swallows’ daily activity patterns. In a habitat dominated by human presence, barn swallows are likely to modify their behavior, often leveraging times when human activities are less frequent. Such alterations can include waking up earlier for food gathering, or adjusting their biological clocks to fit changes in human behavior patterns. Within urban settings, barn swallows may modify their nesting habits to limit encounters with humans. This could translate to irregular nesting times or a shift in nesting locations, both of which add an extra level of difficulty to their already demanding nesting task [

23].

Another potential obstacle for barn swallows in their search for nesting materials is human activity. This is particularly noticeable in urban areas, where natural nesting sites might be supplanted by human-made structures, leaving barn swallows with fewer options for nest building [

24]. Moreover, urban settings might compel barn swallows to cover larger distances to source their nesting materials. Ideally, barn swallows would opt for materials located near their nests, decreasing the overall energy expended on transportation. However, urban development often results in these materials being situated farther from the nests, increasing the difficulty of gathering and transporting nesting materials.

Smaller nests may not offer the same level of space for the chicks as larger nests. This could potentially lead to smaller clutches with fewer eggs being laid, thus diminishing the overall population of barn swallows. This issue raises serious concerns, and could have long-term consequences for the survival and prosperity of barn swallow populations [

25]. Swift urbanization can pose problems, as expanding cities often result in a decrease in natural nesting sites, compelling barn swallows to build smaller nests. This presents a challenge, as urban landscapes are often less accommodating for barn swallow nesting due to the limited presence of natural nesting sites [

26].