Post-Disaster Reconstruction of Residential Buildings: Evolution of Structural Vulnerability on Caribbean Island of Saint Martin after Hurricane Irma

Abstract

:1. Introduction

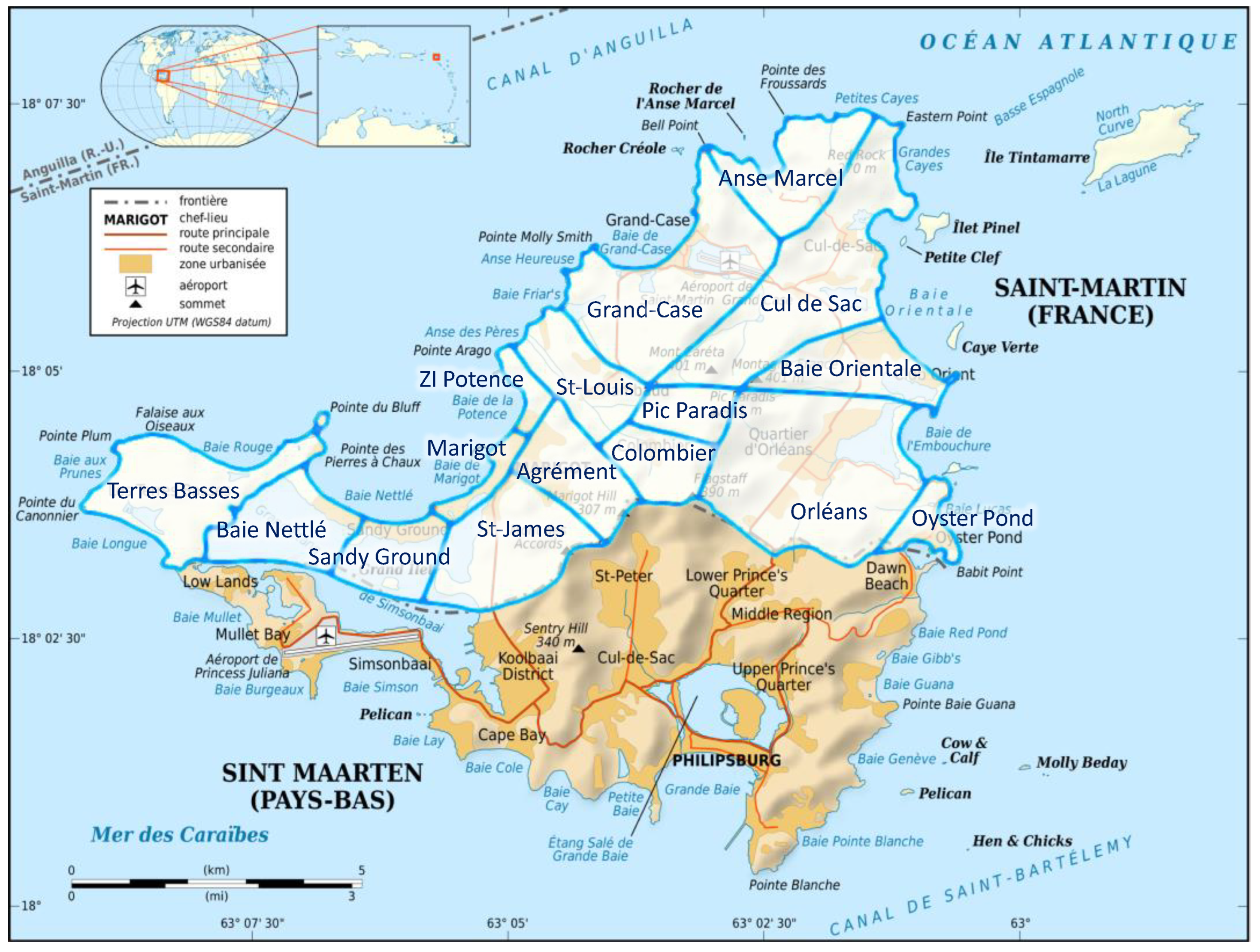

1.1. Irma Hurricane and Saint Martin Island

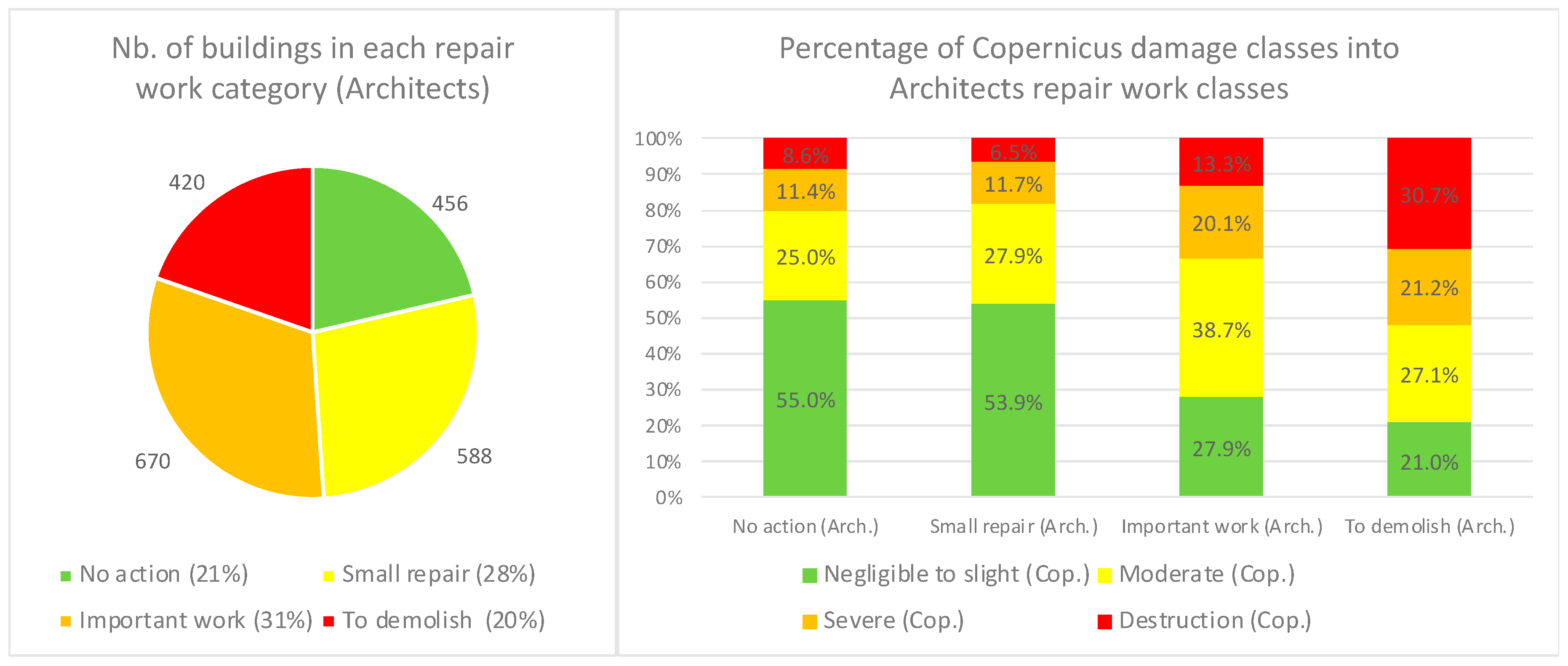

1.2. Evaluation of Structural Damages after Irma

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Interviews with Reconstruction Local Actors

- The first one delved into the aftermath of Hurricane Irma, exploring how the interviewees coped with the event, their expectations regarding the extent of damage to buildings and the island infrastructure, and their perspective on the likelihood of a similar event in the future.

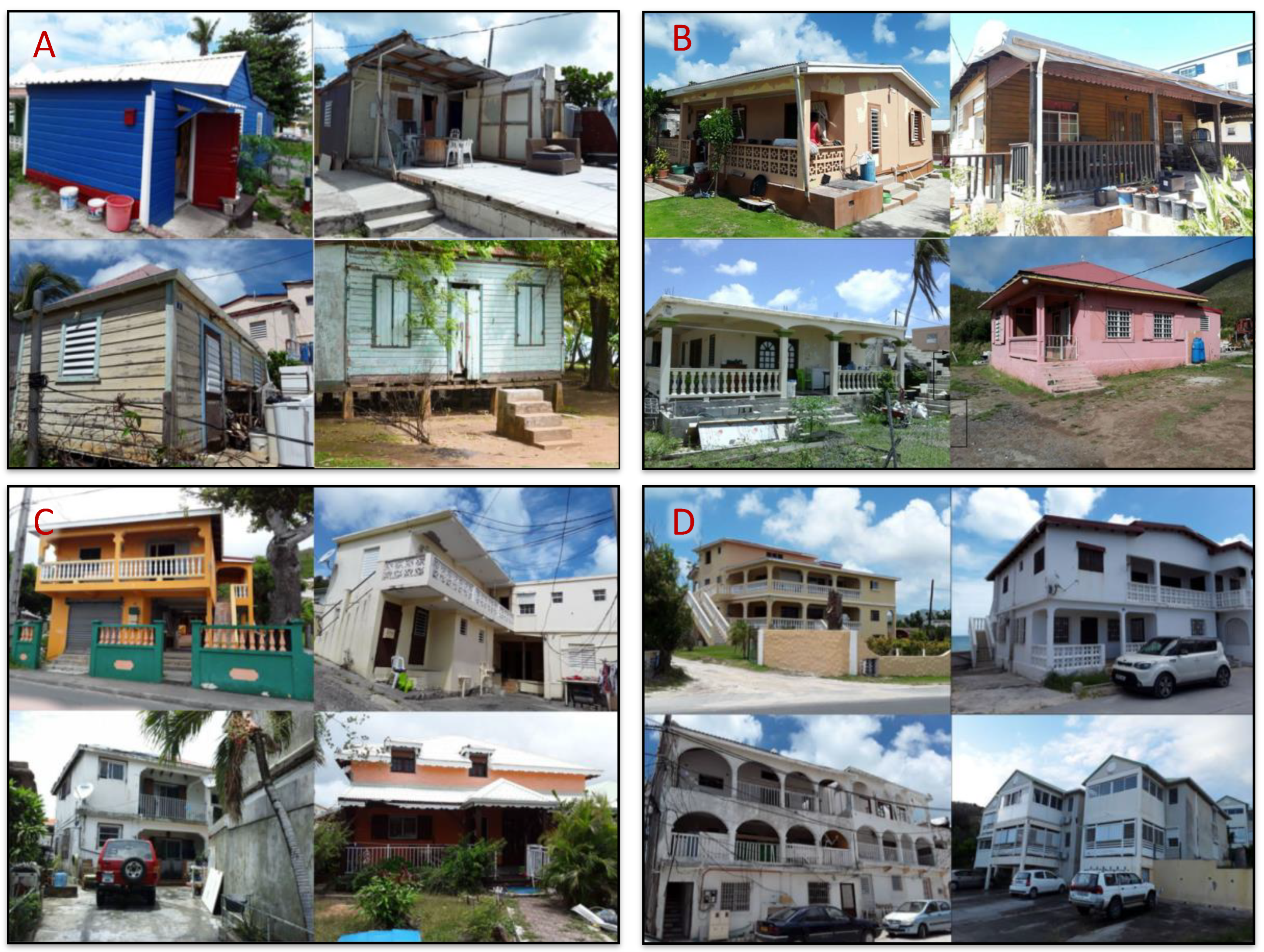

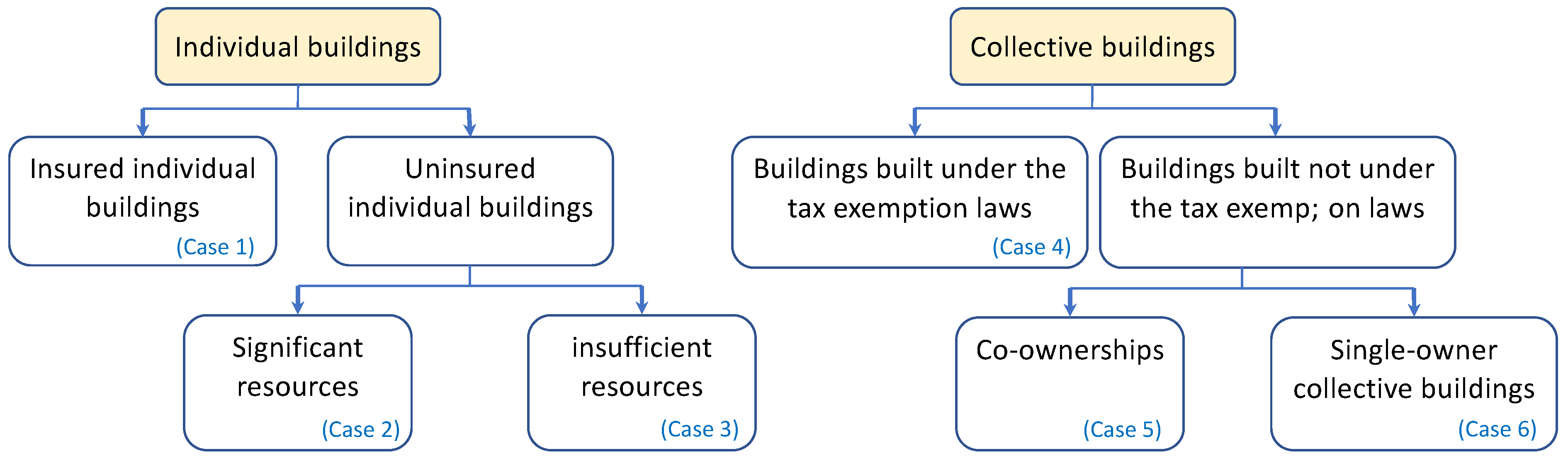

- The second topic centered around the evolution of residential buildings’ vulnerability after Irma. The discussion involved the identification and evaluation of influencing factors such as insurance, material aids, availability of resources (financial, materials, skilled labor, etc.), and administrative procedures. Regarding the evolution of the vulnerability, the interviewees were also asked if they perceived any difference between different districts, different types of buildings, or between different building elements (roof, openings, structure, etc.). The four identified building types are presented in Figure 3.

- The focus of the third topic was on the “Guide to good practices for the construction and rehabilitation of housing” published by the Saint Martin local authority in collaboration with the prefecture (in the French system, a prefecture is an administrative division that represents the central government at the local level). The idea was to evaluate the accessibility, effectiveness, and uptake of these guides.

- The fourth topic focused on the speed and the quality of reconstruction works on the island, including the entities carrying out the work (individuals, construction companies, etc.).

- The final part of the interview addressed general inquiries regarding the interviewees’ overall perception of the current vulnerability of Saint Martin buildings, the coordination between the French state and local authorities, and other related aspects.

2.2. Online Questionnaire

- Profile of respondent, including age, sex, professional situation, nationality, monthly income, etc.

- Duration of their residence on the island, their district, proximity to the sea front, and any changes in their place of residence since Hurricane Irma.

- Details about their current residence, including facilities, equipment, ownership, and occupancy status.

- Whether the respondents were present on the island during Hurricane Irma, had experienced any other hurricane, were prepared or not to face Irma, their expectation regarding the extent of damage to their building, and their perspective on the likelihood of a similar event in the future.

- Typology of their residence based on the four categories presented in Figure 3, as well as the type and characteristics of the roof before and after Irma.

- Overall evaluation of damage to their residence using the five damage classes illustrated in Figure 4; causes of damage, including wind, projectiles, wave shock, rain-induced flooding, marine submersion, etc.

- Detailed assessment of damage level to different parts of their building, such as the roof, walls, foundation, openings, doors, windows, and blackout systems.

- Nature (repairs or reconstruction) and quantity of the required work.

- Commencement of work after Irma, estimated duration, and progress made.

- The respondents’ perception of the quality of work and the evolution of the cyclone vulnerability of their residence.

- Their awareness of existing reconstruction guides.

- Their perception of the current vulnerability of their building and the entire island.

- The last part of the questionnaire focused on the identification of factors impacting the quality, cost, and duration of works (such as financial aids, insurance compensation, etc.) and assessed their significance. At the end of the questionnaire, respondents were given the option to express their interest in being informed about the project’s progress and obtained results, as well as their willingness to be contacted for further sharing of information about their experience with Hurricane Irma.

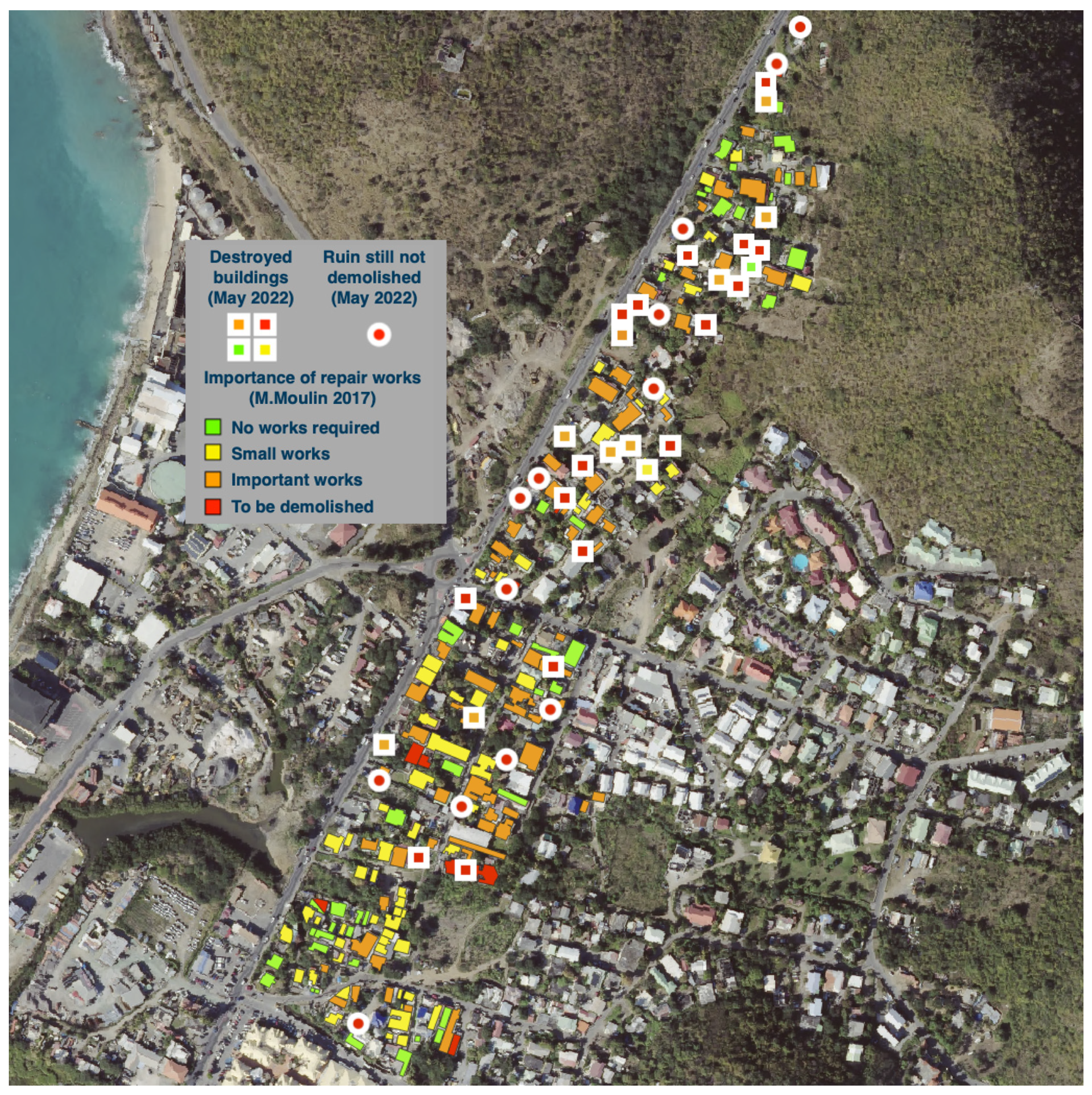

2.3. Field Survey

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of the Interviews with Local Actors

- Insured individual buildings: In the first case, the insurance compensation is globally very satisfactory, having allowed fairly quick compensation and repairs (less than one year). Longer duration works were possible when they concerned a complete reconstruction. However, some specific cases have been reported as buildings still in ruins 5 years after Irma, even though the owner was insured. This situation is confirmed by insurers who observe a lower rate of compensation for Irma than for other natural disasters, proof that some insureds did not request the complementary compensation (30%) which is only paid if the work is carried out.

- Uninsured individual buildings having sufficient personal resources. The second and third cases correspond to populations that are not covered by insurance for various reasons: personal choice to “self-insure”, lack of resources to insure themselves, and lack of the legal property title that gives them the right to be insured. It should be noted that the phenomenon of “no-insurance” is quite widespread in the West Indies [57]. In the absence of insurance, the determining factor for rapid and high-quality reconstruction is the availability of personal resources to finance repairs. For households having these resources, repair or rebuild works are fairly quick overall (less than a year). The quality of these repairs appears to fluctuate significantly, as they may call on insufficiently qualified labor or engineers without consulting any architect or engineering consulting office. This situation reflects the phenomenon of self-building, particularly present in popular districts, which consists of building homes without consulting any architect or engineering company, generally using recycled materials.

- Uninsured populations with limited resources: For the third case, repairs are largely incomplete several years after Irma, except in cases where households have been able to benefit from assistance such as that of “Compagnons Bâtisseurs” (“Compagnons Bâtisseurs” is a French non-profit organization that focuses on social housing and community development through construction and renovation projects), whose quality of service is unanimously recognized. However, it should be noted that the buildings concerned were sometimes already in a degraded state before Irma. This prompted us to consider the initial condition of buildings prior to Hurricane Irma in our analysis. From a purely economic point of view, the damage is higher for a well-off household than for one with limited resources. The impact of this damage on quality of life and health, on the other hand, seems to be much more significant for the less well-off households. Moreover, the populations concerned have a feeling of abandonment reinforced by the absence or delays in works that do not fall under the responsibility of the populations (for example, unrepaired pole and electrical wires or telecommunication cables still attached to a palm tree 4 years after Irma, wreckage of a ship in an occupied parcel not evacuated 4 years after Irma).

- Collective buildings are either co-ownerships or buildings belonging to a single owner and for which the units are rented. An important distinction concerns the buildings built under the tax exemption laws (case 4). On the whole, these buildings are judged by the professionals of the construction industry as being of poor quality and globally vulnerable to cyclone risk. This poor quality is explained firstly by reasons of financial profitability, a better quality of construction being associated (rightly or wrongly) with additional costs during construction. A second explanation lies in the initial vocation of these buildings, which were to be used to develop tourism activities and therefore to accommodate occupants out of the hurricane season. This second argument seems appropriate, but the Irma event shows that the problem of the territory is not in reality that of the security of people, since the human toll was limited to a dozen people, the deaths of some of whom are attributable to carelessness (people who refused to evacuate their boat to take refuge on land). The co-ownerships resulting from the tax exemption laws today present a new problem because of housing pressure on the island. The shortage of housing, which is still felt in 2023, associated with the loss of interest of some of these co-ownerships once the duration of the tax exemption has passed, leads to their reuse for permanent housing for rather underprivileged populations. This leads to the juxtaposition of a social vulnerability and a structural vulnerability.

- The co-ownerships resulting or not from the tax exemption laws (cases 4 and 5) have encountered significant difficulties that have penalized the speed of the reconstruction.

- Difficulty in making decisions at the level of the co-ownership due to the remoteness of the co-owners (non-resident or out of the territory after Irma). This situation concerns particularly the co-ownerships resulting from the tax exemption laws.

- Difficulties for some property managers to present documents that comply with all the requirements of the insurance companies.

- For the reconstruction (cases 4 and 5), difficulties were also encountered regarding the remuneration of the companies and the reduction of the vulnerability of the structures that could result from the works.

- Single-owner collective buildings (case 6) fluctuate between the two aforementioned situations. One part corresponds to financial investments by owners who do not wish to invest in their property on a long-term basis. The buildings are not necessarily insured. When they are insured, the indemnities have not necessarily been used to carry out reparation works. It should be noted that the obsolescence of the mentioned buildings is not an obstacle to their renting, given the high demand on the island. When the buildings are insured, and the owner chooses a rehabilitation to reduce vulnerability, he must use his own funds. Some aids have been possible via the Emergency Housing Fund (In French: Fonds Urgence au Logement) allocated to the municipality by the state and paid back to the owners. This strategy seems to have been carried out with the SEMSAMAR (since its creation in 1985, the SEMSAMAR (Société d’Économie Mixte de Saint-Martin) has been a developer and real estate operator in Saint Martin) buildings, for which main structural improvements concern the reduction of the roof overhang, the replacement of certain frameworks, either by less inclined roofs or by flat terraced roofs, and the use of more resistant joinery. For single-owner collective buildings, another difficulty has also arisen related to the respect of the public procurement procedure. The regulatory or administrative delays between the call for tenders, the consultation of contractors, the attribution of contracts, and the starting of the works delayed the beginning of projects by several months (2–3 minimum—sometimes 6). If we understand the importance of respecting the public procurement code, we also note that this leads to a problematic delay in the reconstruction process, particularly considering the yearly occurrence of hurricane season.

3.2. Synthesis of the Online Survey

3.3. Synthesis of the Field Survey

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, H.; Evans, R. Build Back Better: A Framework for Sustainable Recovery Assessment. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 76, 102998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, D.; Majid, T.A.; Roosli, R.; Samah, N.A. Project Management Success for Post-Disaster Reconstruction Projects: International NGOs Perspectives. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 18, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zokaee, M.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Rahimi, Y. Post-Disaster Reconstruction Supply Chain: Empirical Optimization Study. Autom. Constr. 2021, 129, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Le Dé, L. Whose Views Matter in Post-Disaster Recovery? A Case Study of “Build Back Better” in Tacloban City after Typhoon Haiyan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, W.G.; Van Zandt, S.; Zhang, Y.; Highfield, W.E. Inequities in Long-Term Housing Recovery After Disasters. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2014, 80, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhotray, V.; Few, R. Post-Disaster Recovery and Ongoing Vulnerability: Ten Years after the Super-Cyclone of 1999 in Orissa, India. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2012, 22, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefian, F.F. Initial Organisational Formation of the Housing Reconstruction Programme in Bam. In Organising Post-Disaster Reconstruction Processes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 137–163. [Google Scholar]

- Plein, C. Resilience, Adaptation, and Inertia: Lessons from Disaster Recovery in a Time of Climate Change. Soc. Sci. Q. 2019, 100, 2530–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, Å. Disasters as an Opportunity for Improved Environmental Conditions. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 48, 101590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherchelay, M. La Reconstruction Post-Catastrophe Comme Opportunité? Les Enjeux d’une Reconstruction Durable à Saint-Martin (Antilles Françaises). Ann. Georg. 2022, 3, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L. Disaster as Opportunity? Building Back Better in Aceh, Myanmar and Haiti; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M. Building Back Better: The Large-Scale Impact of Small-Scale Approaches to Reconstruction. World Dev. 2009, 37, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moatty, A.; Grancher, D.; Duvat, V.K.E. Leverages and Obstacles Facing Post-Cyclone Recovery in Saint-Martin, Caribbean: Between the ‘Window of Opportunity’ and the ‘Systemic Risk’? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 63, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, R.S.; DuFrane, C. Disasters and Development: Part 2: Understanding and Exploiting Disaster-Development Linkages. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2002, 17, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisner, B. “Build Back Better”? The Challenge of Goma and Beyond. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 26, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maly, E.; Vahanvati, M.; Sararit, T. People-Centered Disaster Recovery: A Comparison of Long-Term Outcomes of Housing Reconstruction in Thailand, India, and Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 81, 103234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Okada, N. Integrated Relief And Reconstruction Management Following A Natural Disaster. In Proceedings of the Second Annul IIASA-DPRI Meeting “Integrated Disaster Risk Management Megacity Vulnerability Resilience”, International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria, 29–31 July 2002; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Der Sarkissian, R.; Diab, Y.; Vuillet, M. The “Build-Back-Better” Concept for Reconstruction of Critical Infrastructure: A Review. Saf. Sci. 2023, 157, 105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, W.J. Lessons Learned from Tsunami Recovery—Key Propositions for Building Back Better; OCHA: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, E. The Build-Back-Better Concept as a Disaster Risk Reduction Strategy for Positive Reconstruction and Sustainable Development in Zimbabwe: A Literature Study. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 43, 101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, D.; Wang, Q.; Xu, J. Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration in Community Post-Disaster Reconstruction: Case Study from the Longmen Shan Fault Area in China. Environ. Hazards 2018, 17, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklauskas, A.; Amaratunga, D.; Haigh, R. Knowledge model for post-disaster management. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2009, 13, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I. An Overview of Post-disaster Permanent Housing Reconstruction in Developing Countries. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2011, 2, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S. Overseas Development Institute (London, E.H.P.Network). In Housing Reconstruction after Conflict and Disaster; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 085003695X. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, D.P. Fixing Recovery: Social Capital in Post-Crisis Resilience. J. Homel. Secur. Forthcom. 2010, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rouhanizadeh, B.; Kermanshachi, S.; Nipa, T.J. Identification, Categorization, and Weighting of Barriers to Timely Post-Disaster Recovery Process. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil Engineering 2019, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–19 June 2019; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2019; pp. 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, B. A Review of the Literature on Community Resilience and Disaster Recovery. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2019, 6, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huafeng, Z. Household Vulnerability and Economic Status during Disaster Recovery and Its Determinants: A Case Study after the Wenchuan Earthquake. Nat. Hazards 2016, 83, 1505–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.-U.-I.; Haque, C.E.; Nishat, A.; Byrne, S. Social Learning for Building Community Resilience to Cyclones: Role of Indigenous and Local Knowledge, Power, and Institutions in Coastal Bangladesh. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, art5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burby, R.J. Making Plans That Matter: Citizen Involvement and Government Action. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2003, 69, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J. The Role of Communities in Coping with Natural Disasters: Lessons from the 2010 Chile Earthquake and Tsunami. Procedia Eng. 2018, 212, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westercamp, D.; Tazieff, H.; Tazieff, H. Martinique, Guadeloupe: Saint-Martin, La Désirade; Masson: Paris, France, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquon, K.; Gargani, J.; Jouannic, G. Evolution of Vulnerability to Marine Inundation in Caribbean Islands of Saint-Martin and Saint-Barthélemy. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 78, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaba, E. Map in French of the Caribbean Island of Saint-Martin/Sint Maarten, Divided between French and Dutch Halves. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saint-Martin_Island_map-en.svg (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Duvat, V. Le Système Du Risque à Saint-Martin (Petites Antilles Françaises). Développement Durable Et Territ. 2008, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, T.; Pagney Bénito-Espinal, F.; Lagahé, É.; Gobinddass, M.-L. Les Catastrophes Cycloniques de Septembre 2017 Dans La Caraïbe Insulaire Au Prisme de La Pauvreté et Des Fragilités Sociétales. EchoGéo 2018, 46, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouannic, G.; Ameline, A.; Pasquon, K.; Navarro, O.; Minh, C.T.D.; Boudoukha, A.H.; Corbillé, M.A.; Crozier, D.; Fleury-Bahi, G.; Gargani, J.; et al. Recovery of the Island of Saint Martin after Hurricane Irma: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangialosi, J.P.; Latto, A.S.; Berg, R. National Hurricane Center Tropical Cyclone Report, Hurricane Irma; National Hurricane Center: Miami, FL, USA, 2021.

- Der Sarkissian, R.; Cariolet, J.M.; Diab, Y.; Vuillet, M. Investigating the Importance of Critical Infrastructures’ Interdependencies during Recovery; Lessons from Hurricane Irma in Saint-Martin’s Island. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 67, 102675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvat, V.; Pillet, V.; Volto, N.; Krien, Y.; Cécé, R.; Bernard, D. High Human Influence on Beach Response to Tropical Cyclones in Small Islands: Saint-Martin Island, Lesser Antilles. Geomorphology 2019, 325, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L. Community Resilience, Natural Hazards, and Climate Change: Is the Present a Prologue to the Future? Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2020, 74, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moatty, A.; Grancher, D.; Virmoux, C.; Cavero, J. Bilan Humain de l’ouragan Irma à Saint-Martin: La Rumeur Post-Catastrophe Comme Révélateur Des Disparités Socio-Territoriales. Géocarrefour 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijndam, S.; van Beukering, P.; Fralikhina, H.; Molenaar, A.; Koetse, M. Valuing a Caribbean Coastal Lagoon Using the Choice Experiment Method: The Case of the Simpson Bay Lagoon, Saint Martin. J. Nat. Conserv. 2020, 56, 125845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargani, J. Inequality Growth and Recovery Monitoring after Disaster Using Indicators Based on Energy Production: Case Study on Hurricane Irma at the Caribbean in 2017. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 79, 103166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargani, J. Impact of Major Hurricanes on Electricity Energy Production. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 67, 102643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desarthe, J. Les Temps de La Catastrophe. EchoGéo 2020, 51, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustin, P. Repenser Les Iles Du Nord Pour Une Reconstruction Durable. Délégation Interministérielle à La Reconstruction de Saint-Barthélémy et de Saint-Martin. 2017. Available online: https://www.gouvernement.fr/sites/default/files/contenu/piece-jointe/2017/11/rapport_de_philippe_gustin_delegue_interministeriel_a_la_reconstruction_21_novembre_2017.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Gong, L.; Wang, C.; Wu, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q. Earthquake-Induced Building Damage Detection with Post-Event Sub-Meter VHR TerraSAR-X Staring Spotlight Imagery. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, W.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X. Building Damage Detection from Post-Event Aerial Imagery Using Single Shot Multibox Detector. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ci, T.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. Assessment of the Degree of Building Damage Caused by Disaster Using Convolutional Neural Networks in Combination with Ordinal Regression. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilon, S.; Nex, F.; Kerle, N.; Vosselman, G. Post-Disaster Building Damage Detection from Earth Observation Imagery Using Unsupervised and Transferable Anomaly Detecting Generative Adversarial Networks. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, F.; Péroche, M.; Candela, T.; Rey, T.; Freddy, V.; Gherardi, M.; Defossez, S.; Lagahé, E.; Pradel, B. Drone et Cartographie Post-Désastre: Exemples d’applications Sur Un Territoire Cycloné (Petites Antilles Du Nord, Ouragan Irma, Septembre 2017). Cart. Géomatique. 2022. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-03607811 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Candela, T.; Leone, F.; Péroche, M.; Robustelli, M. Mapping a Hurricane Territory: Saint-Martin after the Hurricane Irma (Northern West Indies, Sept. 2017). Mappemonde 2022, 134, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulin, M. Diagnostic Bâti de l’île de Saint-Martin, Suite Au Passage de l’ouragan Irma. 2018. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Deck, O. 4 Ans Après Irma—Leçons Relatives Au Relèvement Des Bâtiments et Des Infrastructures. In Proceedings of the Colloque Ouragans 2017, Champs-sur-Marne, France, 2022. Available online: https://anr.fr/fr/agenda/colloque-ouragans-2017-catastrophe-risque-et-resilience-les-21-et-22-novembre-2022/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- COPERNICUS EMSN 049—Reconstruction Monitoring of St Martin and St Barthelemy Islands (Post IRMA)—STAGE 01 INTERMEDIATE REPORT (2018) et STAGE3—FINAL REPORT (2019). Available online: https://emergency.copernicus.eu/mapping/list-of-components/EMSN049 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Colrat, A.; Jagorel, Q.; Banoun, S.; Payet, C.; Mars, G. Le Phénomène de Non-Assurance Dans Les Départements et Collectivités d’Outre-Mer. 2020. Available online: https://www.igf.finances.gouv.fr/files/live/sites/igf/files/contributed/IGF%20internet/2.RapportsPublics/2020/2019-M-056-03_Non_assurance_Dom-Com-.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Eriksen, C.; McKinnon, S.; de Vet, E. Why Insurance Matters: Insights from Research Post-Disaster. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2020, 35, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros, L.M.S.; Poleacovschi, C.; Weems, C.F.; Zambrana, I.G.; Talbot, J. Evaluating the Interaction Effects of Housing Vulnerability and Socioeconomic Vulnerability on Self-Perceptions of Psychological Resilience in Puerto Rico. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 84, 103476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taki, A.; Doan, V.H.X. A New Framework for Sustainable Resilient Houses on the Coastal Areas of Khanh Hoa, Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, D.H.; Wilkinson, S.; Raftery, G.M.; Potangaroa, R. Building Back towards Storm-Resilient Housing: Lessons from Fiji’s Cyclone Winston Experience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 33, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevatt, D.O. Improving the Cyclone-Resistance of Traditional Caribbean House Construction through Rational Structural Design Criteria. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1994, 52, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosowsky, D.; Schiff, S. What Are Our Expectations, Objectives, and Performance Requirements for Wood Structures in High Wind Regions? Nat. Hazards Rev. 2003, 4, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkharboutly, M.; Wilkinson, S. Cyclone Resistant Housing in Fiji: The Forgotten Features of Traditional Housing. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 82, 103301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; McDonnell, T. Prospects and Constraints of Post-Cyclone Housing Reconstruction in Vanuatu Drawing from the Experience of Tropical Cyclone Harold. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 8, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N. | Interviewee’s Position/Responsibilities | Interview Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Manager of SEICMO (design, engineering, and consulting in construction and project management company) | May 2021 |

| 2 | Territorial engineer in charge of Saint Martin land use and urban planning department | June 2021 |

| 3 | Head of the Saint Barthélemy and Saint Martin territorial unit—DEAL of Guadeloupe | July 2021 |

| 4 | Director, Compagnons Bâtisseurs | June 2021 |

| 5 | Head of Habitat Construction, Saint Barthélemy and Saint Martin territorial unit—DEAL of Guadeloupe | August 2021 |

| 6 | Director of Operations, Semsamar (urban planner, public housing provider, and building promoter) | May 2022 |

| 7 | Director of Tackling Insurance in Saint Martin | May 2022 |

| 8 | Director, Sprimbarth Agency (estate agency in St. Martin) | May 2022 |

| 9 | Ex. President of the Sandy Ground neighborhood council | May 2022 |

| 10 | Architect in Saint Martin | June 2021 |

| 11 | Construction company in Saint Martin | June 2021 |

| 12 | Architect in Saint Martin | July 2021 |

| 13 | France Assureurs—Home and Overseas Risk Manager | February 2022 |

| 14 | Ex. President of the Grand Case neighborhood council | May 2022 |

| How Long Have You been on the Island? | Native | Arrived before 1986 | Arrived before 2006 | Arrived before 2017 | Arrived after 2017 |

| 55% | 19% | 15% | 9% | 3% | |

| Did you experience cyclone IRMA? | Yes | No | |||

| 90% | 10% | ||||

| Do you think a cyclone of IRMA’s intensity could happen again in the next few years? | Yes | In 10–20 years | No | ||

| 75% | 23% | 2% |

| Are You… | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| satisfied with the reconstruction of St. Martin? (115 responses) | 19% | 79% |

| satisfied with the community’s management of the reconstruction? (113 responses) | 15% | 81% |

| satisfied with the government’s management of the reconstruction? (11 responses) | 17% | 73% |

| Do you think that... | Yes | No |

| the residents of Saint Martin are generally better protected than before Irma? (114 responses) | 10% | 66% |

| the authorities of Saint Martin are better prepared to deal with natural disasters? (112 responses) | 17% | 58% |

| a tool such as the PPRN (natural hazard prevention plan) is needed to ensure that construction is more adapted and better located? (111 responses) | 75% | 8% |

| the prevention of natural hazards is compatible with the economic development of Saint Martin? (109 responses) | 61% | 22% |

| Owner | Renter | |

| % having completed repair/reconstruction work (127 replies) | 68% | 51% |

| % having started work after 2 years following Irma (95 responses) | 7% | 18% |

| % covered by insurance at the time of Irma (111 responses) | 84% | 46% |

| % of uninsured who have taken out insurance since Irma (38 responses) | 67% | 65% |

| % having confidence in the reduction of their dwelling vulnerability after reconstruction/repair (108 responses) | 59% | 36% |

| Satisfaction with the insurance compensation amount (score out of five; 68 responses) | 3.2 | 2.7 |

| Satisfaction with delay of insurance payments (score out of five; 68 responses) | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Feeling of safety in dwelling with regard to cyclonic hazards (score out of five (five: very satisfied); 115 responses) | 3.2 | 2.8 |

| Less Important than I Expected | As Important as I Expected | More Important than I Expected | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind damage to your building | 18% | 30% | 52% |

| Damage to your building due to marine submersion | 15% | 23% | 62% |

| Wind damage on the island of St. Martin | 7% | 15% | 78% |

| Damage to the island of St. Martin due to marine submersion | 7% | 24% | 68% |

| Duration of Repair/Reconstruction Work on Your Building? ** | Over 5 Years | 2–5 Years | 1–2 Years | 6–12 Months | Less than 6 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21% | 10% | 15% | 16% | 39% |

| Very Dissatisfied | Somewhat Dissatisfied | Neither Satisfied nor Dissatisfied | Somewhat Satisfied | Very Satisfied | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of repair of damage to your home | 4% | 12% | 36% | 29% | 19% |

| Overall quality of St. Martin reconstruction | 1% | 4% | 51% | 35% | 9% |

| Overall speed of St. Martin reconstruction | 29% | 29% | 24% | 11% | 7% |

| % of Buildings Requiring Repair (x/104) ** | Individuals | Associations | Professionals | Not Carried Out | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roof-covering works | 71% | 38% | 4% | 58% | 0% |

| Roof-structure works | 48% | 32% | 2% | 66% | 0% |

| Opening/blackout works | 54% | 43% | 4% | 52% | 2% |

| Window/opening works | 58% | 45% | 2% | 52% | 2% |

| Structure-wall/partition works | 24% | 48% | 0% | 52% | 0% |

| Structure-foundation works | 3% | 67% | 0% | 33% | 0% |

| Structure-added element works | 35% | 42% | 0% | 58% | 0% |

| Very Unfavorable (Increased Vulnerability) | Somewhat Unfavorable | Useless or without Influence | Somewhat Favorable | Very Favorable (Decrease in Vulnerability) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance indemnities (amount) | 7% | 17% | 24% | 21% | 31% |

| Insurance indemnities (payment dates) | 4% | 15% | 30% | 11% | 41% |

| % of Dwellings That Needed/Asked for This Resource | Very Unfavorable (Increase in Vulnerability) | Somewhat Unfavorable | Unnecessary or without Influence | Rather Favorable | Very Favorable (Decrease in Vulnerability) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sufficiency of personal resources | 70% | 15% | 21% | 16% | 29% | 19% |

| Sufficiency of loans | 15% | 25% | 31% | 6% | 31% | 6% |

| Sufficiency of mutual financial assistance | 23% | 21% | 0% | 8% | 33% | 38% |

| Donations of materials | 16% | 53% | 6% | 6% | 29% | 6% |

| Material aid from associations | 19% | 40% | 5% | 5% | 15% | 35% |

| Material aid from the district council | 13% | 69% | 15% | 8% | 8% | 0% |

| Very Unfavorable (Increase in Vulnerability) | Somewhat Unfavorable | Unnecessary or without Influence | Somewhat Favorable | Very Favorable (Decrease in Vulnerability) | Number of Answers to Question | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building permit simplification | 3% | 0% | 44% | 15% | 38% | 39 |

| Other (administrative) | 6% | 6% | 72% | 17% | 0% | 18 |

| Availability of quality building materials | 0% | 13% | 21% | 27% | 39% | 71 |

| Availability of labor (quantity) | 1% | 10% | 33% | 34% | 21% | 67 |

| Availability of labor (quality) | 1% | 8% | 19% | 41% | 30% | 73 |

| Familiarity of residents with good reconstruction practices | 5% | 9% | 14% | 32% | 41% | 22 |

| Good practices of specialists/companies (engineering skills) | 0% | 2% | 20% | 43% | 35% | 46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mehdizadeh, R.; Deck, O.; Pottier, N.; Péné-Annette, A. Post-Disaster Reconstruction of Residential Buildings: Evolution of Structural Vulnerability on Caribbean Island of Saint Martin after Hurricane Irma. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712788

Mehdizadeh R, Deck O, Pottier N, Péné-Annette A. Post-Disaster Reconstruction of Residential Buildings: Evolution of Structural Vulnerability on Caribbean Island of Saint Martin after Hurricane Irma. Sustainability. 2023; 15(17):12788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712788

Chicago/Turabian StyleMehdizadeh, Rasool, Olivier Deck, Nathalie Pottier, and Anne Péné-Annette. 2023. "Post-Disaster Reconstruction of Residential Buildings: Evolution of Structural Vulnerability on Caribbean Island of Saint Martin after Hurricane Irma" Sustainability 15, no. 17: 12788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712788

APA StyleMehdizadeh, R., Deck, O., Pottier, N., & Péné-Annette, A. (2023). Post-Disaster Reconstruction of Residential Buildings: Evolution of Structural Vulnerability on Caribbean Island of Saint Martin after Hurricane Irma. Sustainability, 15(17), 12788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712788