Abstract

An increasing number of health professionals advocate for psychosocial attention as a vital part of treating mental health illnesses and not only a pharmacological intervention. Drama therapy offers a space where patients can improve socially, physically, and mentally, thus reaching a complete state of wellbeing. So, we aimed to design and evaluate a drama therapy program to develop assertiveness, quality of life, and social interaction in patients suffering from mental health decline. The study was performed under a participatory action design and a critical focus using a case study methodology that required a pretest–posttest and tracking of activities during the whole process. The results suggest that there was a rise in social interactions, an improvement in the quality of life and, significantly, assertiveness, perception of dependency, and isolation. The program improves the assertiveness of the participants and helps a person to feel less isolated and more independent. We conclude that the creation works help them to know themselves and favors their improvement.

1. Introduction

The third goal of the sustainable development agenda is “health and wellbeing”. Its purpose is to ensure healthy lives and promote the wellbeing of all people, which is essential for sustainable development. Among the goals is to prevent, treat, and promote mental health and wellbeing.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1], one in eight persons will suffer some mental disorder at one point in their lifetime. These rates of conditions increased by more than 25% in the first year of the pandemic.

Mental health is a state of mental wellbeing that enables people to cope with the stresses of life, to realize their abilities, to learn well and work well, and to contribute to their communities [1] (p. 8).

Mental health is more than the absence of mental disorders. It is an essential component for a person to be able to develop, cope with life’s stresses, identify their capabilities, and think, feel, relate, and actively contribute to their community. Its deterioration directly affects physical and social health. Mental health is a fundamental human right. And without it, a person cannot develop a complete state of health and wellbeing [1,2,3].

Mental illness is a severe global public health problem that increasingly affects the health and wellbeing of people worldwide regardless of the status of the country to which they belong [4].

A person with mental illness lives in a permanent state of discomfort. That is because their health and wellbeing are affected. Mental illness causes various deficits and disturbances in a person that deteriorate their quality of life. These generate a deterioration in their social functioning, isolation and social exclusion, loss of interest, higher unemployment rates, low self-esteem, deterioration of identity, emotional flattening, poorer quality of life, more physical illnesses, increased dependency and psychological distress, and dissatisfaction with life [5,6,7]. In many cases, social stigma often worsens the situation. This stigma causes the person to develop self-stigma and devalue themselves, decreasing their grade of life satisfaction [3,8].

According to the DSM-5 TR manual from the American Psychiatric Association [9] and the World Health Organization’s Constitution [2], mental health is influenced by social, political, cultural, and economic factors.

In recent years the concept of recovery has acquired a positive character, and it emerges as a process of self-improvement. The objective is not to return to the starting point but to acquire a new meaning and purpose in life, going beyond the effects. To be able to identify the meaning of life and understand that one’s own life has value is central to the recovery process. Successful recovery leads the person to think, react and behave differently in real situations and not only in recovery processes [10]. The World Health Organization emphasizes the significance of developing services and interventions that support clinical treatment and promote recovery [2].

Experts are increasingly advocating for psychosocial interventions as a treatment for mental disorders rather than depending solely on medication to alleviate symptoms. The idea is that an integral treatment will increase the strengths of the person in such a way that they will understand and accept their situation, creating and establishing purposes that give meaning and value to their lives [11,12,13], thus improving their functioning and reaching a state of wellbeing [14,15].

1.1. Drama Therapy

Drama therapy is the intentional use of theatrical processes to reach therapeutic goals. Its interdisciplinary nature contains influences from psychotherapy, occupational therapy, and theater. This interdisciplinarity allows the flourishing of the healing potential implicit in the theatrical processes [16] (pp. 154–155).

An aspect differentiating this therapy from others is that it does not focus on the problem. It focuses the therapeutic process on the positive aspects of the people, understanding that the development of these personal facets offers a recovery process and conflict transformation. During the process, the body and mind are considered equally important [17,18,19]. Drama therapy accords the same importance to the three components in the definition of health, physical, mental, and social [2], and promotes interpersonal relations, allowing the patient to reach a state of wellbeing in all three areas.

1.2. Assertiveness

Assertiveness plays an essential role in interpersonal relationships and is considered one of the basic social skills.

A decline in assertive skills can cause, among other problems, impairment in social relations, high-stress levels, lack of self-affirmation, social phobia, difficulties in established relations, or low self-esteem [20].

Assertiveness is the capacity to defend personal rights, establish healthy interpersonal relations, develop communication skills, solve conflicts, and openly express ideas, feelings, and beliefs, in such a way that sincerity does not nullify or harm the rights of others [18] (p. 159).

A person that develops and internalizes assertive behaviors can face a variety of situations positively, experimenting at the same time with an improvement in their emotional functioning, an increase in self-esteem, and a decrease in social anxiety, aggressiveness, and stress [20,21,22]. We have been unable to find any study on the use of drama therapy to improve assertiveness in adults suffering from mental illnesses.

Hypothesis 1.

Patients suffering from a decline in mental health and participating in a drama therapy program improve their assertiveness.

1.3. Quality of Life

Mental illnesses can cause a range of deficiencies and disorders that can negatively impact physical, social, and mental functioning. This decline can ultimately affect the overall quality of life [2,6,23].

One of the main barriers causing a decline or damage in the quality of life is stigma or self-stigma. The subjective process in question can limit social circles and patients, impeding personal growth and integration and ultimately preventing any improvement in quality of life [11,24,25,26].

A decline in the quality of life is not a symptom of mental illness but a consequence of the several deficiencies caused by a mental disorder. Various reasons can lead to a person feeling low self-esteem, a lack of confidence, a decline in social connections, a sense of purposelessness, reliance on others, and societal judgment, among other factors. It is common for patients to feel socially isolated, neglect their health, and distance themselves from others due to this experience. Experiencing these drawbacks can negatively impact an individual’s wellbeing and overall quality of life [18,21,26,27].

According to recent studies, the goal of recovery is to enhance the quality of life [28].

We could not find a drama therapy program that catered to improving the quality of life of adult patients affected by mental illness. However, there are drama therapy programs on mental health to improve the quality of life of adolescents and children [29]. Furthermore, Butler [30] shows the benefits of drama therapy in the recovery of patients affected by schizophrenia and, in particular, on their quality of life.

Hypothesis 2.

Patients suffering from a decline in mental health and participating in a drama therapy program improve their quality of life.

1.4. Social Interaction

By nature, humans are social beings; so, a social deficit causes a decline in social skills and, consequently, in the development of a person [20,31].

Social integration makes a person feel like a significant part of an environment and is a decisive factor in personal recovery [32]. The recovery process relies on three interconnected aspects: the integration of physical, social, and psychological factors. A decline in one of the three is enough to cause a decrease in social integration, in many cases ending in social exclusion [33,34]. In contrast, the positive development of social interaction is related to wellbeing, commitment, good self-esteem, or confidence, hence the importance of building spaces that allow a person to develop and create social relations [33,34].

Drama therapy has been used in various programs to enhance social interaction. In the concrete case of adults with schizophrenia, we found programs for improving social interactions through drama therapy [35,36].

Hypothesis 3.

Patients suffering from a decline in mental health and participating in a drama therapy program improve their social interaction.

On the other side, many studies support the efficiency of the arts in the recovery from mental illnesses, and more concretely, they endorse the benefits and improvements in negative and cognitive symptoms when working with drama therapy [37,38,39].

Those programs show that drama therapy and the theater offer patients the opportunity to find out and improve their strengths, their own identity, their social skills, their aims and goals, their emotional expression, or their creativity [19,40,41,42]. Those skills support the development of social competencies and improve the quality of life for a person suffering from mental distress.

Given the need for programs for the psychosocial development of those suffering from mental distress and the possibilities offered by drama therapy as an intervention tool, we aim to determine the efficiency and usefulness of a drama therapy program to develop assertiveness, quality of life, and social interactions of that group of patients.

Below, we present a drama therapy program designed and evaluated for individuals experiencing declining mental health.

2. Materials and Methods

The problem subject of this study is addressed under a critical focus and analyzed under a participatory action research design through a group case study methodology requiring a pretest–posttest and a close tracking of the activities during the whole process. The empirical evaluation uses qualitative and quantitative instruments.

From a critical approach, the aim is to identify the problems of a specific reality and transform them by providing solutions that improve the social and personal processes of the contexts in which the intervention takes place. During this process, participants become active subjects generating change from a reflective practice [43].

Empirical research allows an in-depth investigation of a contemporary and concrete event in its natural context, favoring a better similarity between the sample and reality. This ability to analyze the situation in depth and approach the event in detail allows us to make contributions of enormous relevance, something that cannot occur in large samples [44].

The case study is not limited exclusively to qualitative research. Therefore, a mixed method that combines quantitative and qualitative procedures is used, as it has become more prevalent in recent times [45]. With this, we do not seek to obtain two types of results; rather, using two approaches allows triangulating the data to corroborate or complement the findings [46].

According to recent data in the drama therapy area, qualitative techniques are the most widely used. These techniques are present in more than 40% of the programs [47].

A mixed-methods approach, in addition to the richness of the results, will provide evidence to support the program’s efficacy. Several authors detect this need and suggest creating a dialogue between both methodologies, thus increasing the outcomes of drama therapy programs [48,49,50].

Based on the above, and even though the sample size does not allow us to generalize results universally, this research seeks to deepen and obtain a wealth of data that will provide us with understanding and seek solutions for the population with deteriorating mental health in Galicia and Spain.

2.1. Population

The 51 participants in the present investigation were 26 men and 25 women. All participants were adult users of mental health centers for psychosocial rehabilitation and suffering from mental health decline.

The decline in mental health was limited to users with a mental disorder diagnosis. Most of the participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

The selection process for the centers was probabilistic, including four mental health centers in four different urban municipalities.

The population sample was purposive, consisting of users of these centers who met the inclusion criteria: being a user of one of the four psychosocial centers and suffering a mental disorder diagnosis.

2.2. Instruments

The evaluation of the program was designed considering the whole intervention program. Qualitative techniques were used to evaluate the process and to evaluate the program efficacy, a pretest–posttest design using quantitative instruments was used.

To measure the quality of life, the Spanish version of the Quality of Life questionnaire Sf12-v1 [51], was used. It is a questionnaire made up of twelve items of Likert-like responses that give us an assessment of health, daily life limitations due to health issues, recent limitations due to physical or mental health, and the level of pain or frequency of discomfort in the last four weeks. The results can be divided into two numerical components: the physical component summary and the mental component summary. In this study, the internal consistency of each component was a = 0.85 for the physical component summary and a = 0.78 for the mental component summary, values that are considered acceptable. This instrument was supplemented by three complementary questions on a scale from 1 to 5 to understand the perception of each participant regarding their general state of health, their level of dependency, and their degree of loneliness. Here, 1 represents a low perception of general health, their level of dependency, and their degree of isolation, and a 5 indicates a high perception of each variable.

To measure assertiveness, we selected the Assertion Inventory by Gambrill and Richey. The Spanish version of the inventory was validated by Carrasco, Clemente, and Llavona [52] for the general population and by Casas-Anguera et al. [53] for a population diagnosed with schizophrenia. The instrument consists of forty items, and the answers are provided on a 5-point Likert scale. It gives information on the assertive behavior of a person using two subscales: the degree of discomfort and the probability of the response to a given social situation. The higher the score, the higher the decline, but a low score indicates good assertive behavior. In the case of this study group, we found high reliability in both scales, being very high in the case of degrees of discomfort. On the scale of degree of discomfort, Cronbach’s alpha was a = 0.915, and the probability of the response was a = 0.799.

The evaluation of social interaction was limited to a qualitative instrument, specifically by the use of an individual observation register to note body postures, physical contact, gestures, voice volume, speech fluency, time speaking, attentiveness towards others, and the number and quality of questions and answers to those questions. The register was elaborated according to the contents of the program and the theoretical framework. Through 9 items, data were collected on the development of each participant in each of the sessions. Each indicator was evaluated through a Likert-type scale from 1 to 5, where 1 is a low development of the skills, while scores up to 5 reflect an improvement or acquisition of these skills.

The assertiveness variable was also measured by using an observation register noting data about the rejection of requests, expressions of personal limitations, initiation of social contact, expression of positive feelings, acceptance of criticisms, disagreement of opinions, being assertive with others, and making criticisms.

Those instruments were supported by a field diary where the educator noted her perceptions on the participation of each subject, discussion groups where the participants reflected on each session, and a 7-question satisfaction questionnaire that was a way to determine their opinion about their therapeutic process.

This combination of techniques allowed for a triangulation of the data, thus increasing the reliability of the results.

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Ethics Committee

The study was carried out according to the standards established by the Declaration of Helsinki, the recommendations of Good Practice of the European Economic Community (EEC), and the Spanish legal regulations in force, and it was approved by the Autonomous Ethics Committee of Research in Galicia (CEIC 002/2019).

2.3.2. Program

The methodology used for the development of this program was active and participative, based on drama therapy techniques. All the program activities were centered on a creative project, starting from the basic principles of cooperation, creativity, socialization, and participation. In this way, the educator becomes a guide, allowing the participants to take responsibility for their work. Instituting them as coparticipants in their learning, they develop values such as responsibility, effort, motivation, and respect, increasing their social skills, wellbeing or self-actualization, etc.

The program, based on drama therapy and specifically designed for those suffering from mental health issues, had as its general aim to find and interiorize skills and abilities in personal and social development to improve assertiveness, social interaction, and quality of life.

The program consisted of 24 weekly sessions that followed a specific therapeutic process, divided into different phases.

2.3.3. Phases of the Therapeutic Process

The project was divided into two parts: creation of the material and collective creation.

The first 8 sessions were devoted to setting the therapeutic agreement, establishing the group, and dealing with different personal characteristics using artistic processes.

The following sessions were devoted to a collective creation based on the material developed in the first part. As a group, they developed a project starting from their group and individual identities.

The project had no fixed limits. Each participant developed by their own capabilities within the group.

2.3.4. Sessions

The sessions were divided into 5 parts. They started by answering the question “How are we today?” using emotion. Afterward, they performed several warmup exercises introducing the central activities of the session. The main part of the session was the development activities that varied according to the current stage of the program. The work part closed with a group discussion about the session, how they felt, and what they gained. The session itself ended with the same question that opened it: how are we now?

2.3.5. Evaluation

The evaluation was structured, following Pino-Juste [54], according to the stage moment in this way:

Initial evaluation: this was performed before the program implementation and was a collection of data from the quantitative instruments: a questionnaire with socioeconomic, demographic, and emotional data, a Quality of Life Questionnaire SF12-v1, and an Assertion Inventory by Gambrill and Rechey.

Formative evaluation: this was performed during the process. This information enabled understanding how the project was going and whether its objectives were being met. At the same time, it offered the opportunity of making corrections so the participants could gain greater benefits. As pointed out, this process was performed using qualitative instruments: a field diary, observation registers, and discussion groups.

Final evaluation: the purpose of this evaluation was to determine whether the aims of the program were met and whether it was complemented by the data gathered during the formative evaluation. The quantitative instruments from the initial evaluation were used, and the participants were asked to fill out a satisfaction questionnaire.

2.3.6. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

A week before starting the program and a week after finishing, the participants filled out an evaluation booklet. During the program, the indicators for each variable were gathered using the field diary, the individual observation register, and the group discussions. After the program, the participants also filled out a satisfaction questionnaire.

All the participants signed the informed release form for their participation and the use of data in the present study.

Data were analyzed anonymously, and each participant was assigned an alphanumeric code.

Descriptive statistics were computed for assertiveness and quality of life variables, as well as for their components. To check the differences between the two independent groups, the parametric Student’s t statistic was used. And to examine the association between categorical variables, the Fisher exact test was used. In all the contrasts performed, a significance level of p < 0.05 was assumed to determine statistical significance. The analysis was performed using the statistical package SPSS version 22.

The data collected in the observational registry and the satisfaction survey are presented in bar graphs. All of them were elaborated using Microsoft Excel version 16.16.27.

3. Results

Next, we describe the results according to the initial hypotheses.

Regarding the assertiveness variable (Table 1), the results were significant in both components, improving assertiveness after the program. For the correct understating of the results, we must remember that a higher mean indicates a more serious problem. Regarding the variable quality of life (Table 1), both components increased in mean, but the differences were not considered significant.

Table 1.

Descriptions and Student’s t for related samples: assertiveness, quality of life, and its components. n = 51.

As seen in the results for degree of discomfort (sig. = 0.002), the mean decreased from 116.2 to 103, 49 points. In addition, there was an almost 20 point decline both in the minimum (Min.pre = 65; Min.post = 47) and its maximums (Max.pre = 174; Max.post = 158). On this scale, the scores were from 40 to 200, and the minimums showed that people had a very low degree of discomfort after going through the program. The second component of the assertiveness variable, the probability of response, also showed significant results (sig. = 0.022), and its mean decreased from = 115.78 points before the program to = 109.43 points after. The minimum value increased, from 73 points at the start to 91 points at the end. So, after going through the program the discomfort in the group was reduced, and the probability of response to different situations improved.

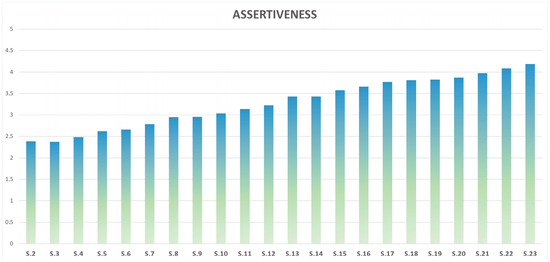

The data gathered in the observation registers supported these results. Figure 1 shows the upward evolution of the means obtained per session about assertiveness. The first mean was = 2.39, increasing to the end of the program to = 4.2. We must consider that contrary to the scale, in the observation register, a higher mean indicates better assertiveness.

Figure 1.

Mean per session of the assertiveness of the group (n = 51) in the observation registers.

The data were further backed by the field diary. For instance, in session five, the register recorded the words of a participant talking during the group discussion after the session ended: “... after the discussion, participant 1HB took the floor saying that it has been very useful for him because for him is hard to say no, he has always been unable and today he could practice through improvisation to say no when he doesn’t want to do it or can’t” (session 5).

Participant 15 MG, in addition to suffering from a delayed response, falls asleep a lot due to medications. But in the field diary, we find this note “During the intermission of session 9, 15 MG showed us a song she had brought with her, and when playing it she danced with so much energy and so much happiness. I have never seen 15 MG so awake and happy. When I used it in the session, I asked her if she wanted to dance, and said yes. While she danced, the rest of the group clapped, shouted nice things, acknowledge her effort, etc. 15 MG was very excited and happy” (session 9).

So, Hypothesis 1, indicating that a drama therapy program improves assertiveness in a person suffering from a mental health decline, is confirmed.

Regarding the variable quality of life, physical health retained its minimum (Min. = 11.67) and increased its maximum and mean (Before the program: Max. 95.83; = 57.74—After the program: Max. 100; = 58.36). Mental health showed a clear decline in its minimums (Before the program: Min. = 8.33; after the program: Min.: = 3.33). In addition, both the maximums and mean increased (Before the program: Max. = 89.17; = 49.69-After the program: Max. = 100; = 54.06).

The data were confirmed by analyzing the results of the complementary questions about the perception of health, dependency, or isolation.

Concerning the state of health of the 51 persons in the group, 24 kept the same opinion about their state of health. The number of persons that raised their perception of health after the program was 18, and only 9 lowered their perception of health after the program.

Regarding the isolation felt by the participants before and after the program of the total group (n = 51), 28 persons kept their initial category, with the persons not feeling isolated the ones that mostly kept their opinion. Twelve persons improved, reducing their isolation level, and 11 increased their level of isolation.

Concerning the opinion about the degree of dependency felt by the participants, 13 persons defined their level of dependency in the same category at the beginning and the end of the program, only 12 said their level of dependency had increased, and 26, more than half the group, declared their level of dependency reduced after the program. After the implementation, over 60% of the group showed low or limited dependency. Of the three variables we have compared in this section, the level of dependency was the one that improved the most. In addition, the group with the highest dependency moved from being the second most common at the start of the program to the least common at the end, declining by half.

Fisher’s exact test was used for the analysis of the three variables. Significant data were obtained for two of the three variables. The degree of isolation was p = 0.000, and the level of dependence was p = 0.010. In contrast, the health status was p = 0.051.

So, Hypothesis 2, indicating that a drama therapy program improves the quality of life of a person suffering from mental health decline, is disproven. But the perception of the state of health, the feeling of isolation, or the feeling of dependency improved.

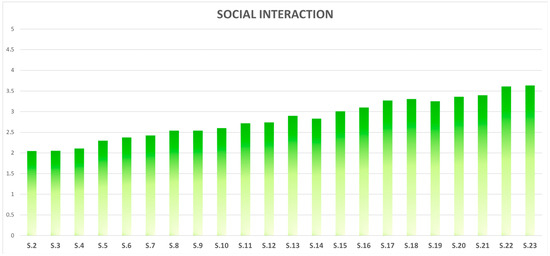

Regarding the social interaction variable (Figure 2), it showed an increase with = 2.04 at the start of the program and a = 3.63 in the last session registered.

Figure 2.

Mean per session of the social interaction of the group (n = 51) in the observation registers.

In session 10, one of the exercises was for a group of four people who had to walk in file very close, holding two sticks over their heads so they would not fall apart. In their comments about the exercise, the participants said:

“In the beginning, the coordination was hard, we stepped on each other and didn’t think about making a plan beforehand. When the educator stopped the exercise and told us it was very important to agree on something, we realized it was true, and slowly we stopped stepping on each other”(Field Diary session 10)

“At the beginning, we were very uncoordinated, but as soon as we stopped thinking about ourselves and started to see what was in front of us, we managed to walk together without getting hurt”(Field Diary session 10)

Several sessions were structured around improvisation pair work. The field diary contained observations by the educator on the evolution of the improvisations from the first sessions to the latest: “During the cold-hot improvisation, there was a marked difference concerning the first improvisations, all could argue why they were cold or hot, they listened to each other, they talked, and most of them offered solutions to resolve a conflict” (Field Diary session 9). In the same session, it says “I was surprised by the improvisations. There was a clear difference from the initial ones. All were able to argue why they were cold or hot, and better or worse, all could offer reasons to get better and find a solution as a pair” (Field Diary session 9).

So, Hypothesis 3, stating that a drama therapy program favors an increase in the social interaction of a patient suffering from a decline in mental health, is confirmed.

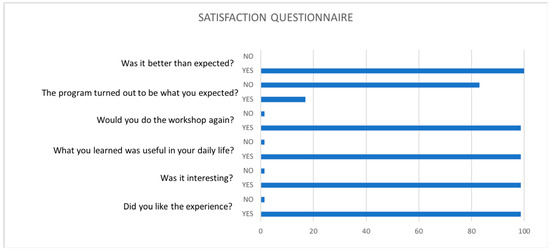

In Figure 3, we show the results of the satisfaction scale.

Figure 3.

Satisfaction questionnaire. Question 1 to 6. Answers yes/no.

In addition, there was an analysis of the results from question 7, “What did you learn?”. The participants said the benefits of the program were to establish relationships during their participation, accept and respect others, express themselves, relax, gain spontaneity, face fears, improve themselves, trust others or overcome fears, among others. Both in general and in each session, the results showed the participants had a very high level of satisfaction.

4. Discussions

Many studies support the efficiency of drama therapy programs on different populations and problems [19], including children traumatized by sexual abuse [55], with behavior problems [56,57], or patients in the psychiatric wing of a hospital [58] and adults suffering from mental illness [35,59,60,61], who were war veterans [62,63], or had dementia [64], among others.

The evaluated program with people suffering from a mental health decline showed a statistically significant efficiency in the increase of assertiveness in its two components, a reduction in discomfort and an increased probability of response. The data from the evaluation process confirmed the same results.

We surmise that the improvements were produced by the possibility offered by the theater to develop oneself from practice, having the opportunity of relating to their partner or living different situations, emotions, and desires, that is, making them feel comfortable and reducing their discomfort about their feelings and environment, improving at the same time their skills for dealing with other situations and anticipating and identifying their own reactions to concrete social situations such as saying no to requests, expressing personal limitations, starting social contacts, expressing positive feelings, accepting criticism, expressing different opinions, being assertive or expressing negative feelings [65].

The mean of the degree of discomfort at the start of our program was even higher than in other studies [53]. In contrast, the values found in the probability of response of the sample were below the mean in the original validation of the instrument used. So, our data corroborate the conclusion by Casas-Anguera et al. [53], which points out that the emotional flattening of those suffering from schizophrenia shows a deficient degree of response probability. Considering these data, we can say that people suffering a decline in mental health, especially those suffering from schizophrenia, show higher degrees of discomfort than the general population, and their level of probability of response is negative. This can be due to not anticipating situations that can produce stress and due to the emotional flattening and the lack of planning that characterize people with mental health problems [53]. This is reflected in the sample as the lower the probability of response was, the higher the discomfort was.

Quality of life always suffers in a diagnosis of mental illness [66]. Recent studies indicate that improving the quality of life is a fundamental objective in the recovery process [28].

No statistically significant changes in quality of life were found after the program, but there were significant changes in the evaluation of the participants about their dependency and their level of isolation. Regarding the level of isolation, even though almost 80% of the group retained or reduced their level of isolation at the end of the program, the group of people feeling not alone declined, with an increase in the group feeling very alone. Even though the level of health did not show a significant different, the data showed that the groups of mildly bad and bad health declined, and the group defining their health positively as mildly good and good increased to 80%. We understand that these results are related to assertiveness and social interaction, because of an increase in social interactions, relationships, and common projects as a collective creation, the time spent alone starts to have negative connotations because they now know what it is like to have positive relationships and how they make one feel [67]. Of the three variables, the level of dependency was the one showing the largest change, reducing the group with the highest dependency by half to being the smallest at the end of the program.

The qualitative data showed a constant increase in social interaction despite the oscillations present during the process. Despite these fluctuations that we attribute to the instability of the illness, the constant increment shows that the program allowed the continuous development of all the participants without exception.

The results indicate that the participant’s social skills improved due to increased social interaction. So, we can affirm that the program favored an increase in assertiveness and the associated variable, quality of life. The results agree with different studies aiming to improve the interaction among pairs, social skills, and social development [35,68].

In this present research, the qualitative evidence, characteristic of drama therapy, was complemented with the quantitative results, creating a combined method of evaluation in drama therapy rarely used in this field, and concretely, in drama therapy programs to improve mental health in Spain, where there are no previous scientific publications in this field.

We want to emphasize that even though assertiveness in its two components, degree of discomfort and the probability of the response to different social situations, showed significant data on the program efficiency, the results showed an increase and evolution in all the variables. We believe that a long-term intervention is needed so variables like quality of life can be interiorized, as removing the associated stigmas takes a long time.

Following the suggestions by Price and Murnan [69], we must point out as a limitation of this research that the spaces used to implement the program limited some of the ideas previously designed. In addition, the size of the groups forced some sessions to be performed in turns or in two rooms at the same time. On the other hand, the limited number of previous research studies on this topic, especially on the Spanish population, prevented us from controlling possible additional variables. Those limitations make clear the need to publish further on drama therapy interventions in a mental health area. We also point to the lack of instruments adapted to our needs that could measure social interaction. There are some instruments to measure those variables, but we were unable to find instruments adapted to our population that could evaluate the specific contents of our program. Finally, the size of the sample was a limitation. Although it allows us depth, a small sample makes it difficult to generalize the results.

These limitations make it necessary to consider some future actions important for future implementation of the drama therapy program. Some of these include a larger sample, a long-term evaluation that allows confirming the results obtained over time, and the possibility of carrying out multiple assessments after drama therapy.

5. Conclusions

The data show a population with deteriorated mental health. This group has low assertiveness, a low likelihood of responding to various social situations, and experiences of a high level of discomfort. They manifest a low quality of life, with lower mental health than physical health.

The evaluation of the drama therapy program showed a statistically significant difference in the reduction in discomfort and the probability of the response to different social situations, that is, the two components of assertiveness. It is important to remember that being assertive is directly tied to having a better quality of life.

Additionally, this evaluation discovered significant statistical differences in how participants perceive their level of dependency and isolation. The results allow us to conclude that the program helps people feel less lonely and more independent. These variables are directly related to the analyzed constructs of quality of life.

We conclude that the creation work allows people to know themselves better and nudges them to improve. This work becomes a reference for success and personal improvements in their lives.

The satisfaction with the program has been very high, and the involvement of the participants has also been very high with oscillations derived from the specific characteristics of the population.

This study provides significant evidence of the effectiveness of drama therapy in improving the psychological, social, and personal aspects of individuals experiencing mental health decline and social exclusion. This approach promotes full development and social inclusion, leading to sustainable wellbeing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F.-A. and M.P.-J.; Formal analysis, S.F.-A. and M.P.-J.; Investigation, S.F.-A. and M.P.-J.; Methodology, S.F.-A. and M.P.-J.; Writing—original draft, S.F.-A.; Writing—review and editing, M.P.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality reasons.

Acknowledgments

To the mental health associations and to the people who participated in this program in a disinterested way.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report. Transforming Mental Health for All. Technical Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338 (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- World Health Organization. Basic Documents 49th Edition. Technical Report. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/ (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Chan, K.K.S.; Tsui, J.K.C. Longitudinal impact of experienced discrimination on mental health among people with mental disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 322, 115099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteford, H.A.; Ferrari, A.J.; Degenhardt, L.; Feigin, V.; Vos, T. The Global Burden of Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Disorders: An Analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, C.C.H.; Fung, W.T.W.; Leung, D.C.K.; Chan, K.K.S. The impact of stigma on engaged living and life satisfaction among people with mental illness in Hong Kong. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 32, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.S.C.; Hermens, D.F.; Scott, J.; O’Dea, B.; Glozier, N.; Scott, E.M.; Hickie, I.B. A transdiagnostic study of education, employment, and training outcomes in young people with mental illness. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glozah, F.N.; Pevalin, D.J. Association between psychosomatic health symptoms and common mental illness in Ghanaian adolescents: Age and gender as potential moderators. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chio, F.H.N.; Mark, W.W.S.; Chan, R.C.H.; Tong, A.C.Y. Unraveling the insight paradox: One-year longitudinal study on the relationships between insight, self-stigma, and life satisfaction among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 197, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–DSM 5-TR; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, D.; Reeve, S.; Robinson, A.; Ehlers, A.; Clark, D.; Spanlang, B.; Slater, M. Virtual reality in the assessment, understanding, and treatment of mental health disorders. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2393–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Or, S.E.-B.; Hasson-Ohayon, I.; Feingold, D.; Vahab, K.; Amiaz, R.; Weiser, M.; Lysaker, P.H. Meaning in life, insight and self-stigma among people with severe mental illness. Compr. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, B.L.; Pullen, E.; Pescosolido, B.A. Interactions between patients’ experiences in mental health treatment and lay social network attitudes toward doctors in recovery from mental illness. Netw. Sci. 2017, 5, 355–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A.E. Nonprecsion (Standar) Psychosocial Interventions for the Treatment of Mental Disorders. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2022, 24, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.; Brazier, J.; O’Cathain, A.; Lloyd-Jones, M.; Paisley, S. Quality of life of people with mental health problems: A synthesis of qualitative research. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2012, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengistu, M.E.; Berassa, S.H.; Kassaw, A.T.; Dagnew, E.M.; Mekonen, G.A.; Birarra, M.K. Assessments of functional outcomes and its determinants among bipolar disorder patients un Northwest Ethiopia comprehensive specialized hospitals: A multicenter hospital-based study. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2023, 22, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Aguayo, S. Programa de dramaterapia para personas con deterioro de su salud mental. In Diseño y Evaluación de Programas Educativos en el Ámbito Social: Actividad Física y Dramaterapia; Pino-Juste, M., Ed.; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 153–195. [Google Scholar]

- Cornejo, S.; Brik Levy, L. La Representación de las Emociones en la Dramaterapia; Editorial médica Panamericana: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Aguayo, S. Drama como Técnica Terapéutica en Salud Mental: Diseño y Evaluación de un Programa. Ph.D. Thesis, University de Vigo, Vigo, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Orkibi, H.; Keisari, S.; Sajnani, N.; Witte, M. Effectiveness of Drama-Based Therapies on Mental Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Studies. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, M.; Emami, M.; Bonakdar, S.A. Effectiveness of Narrative Therapy on the Increase of Self-Assertiveness in Female High School Students (Case Study: Iran (Isfahan), 2013–2014). Int. J Acad. Res. Psychol. 2014, 2, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, M.; Ghayas, S.; Adil, A.; Niazi, S. Self-efficacy and Mental health among university students: Mediating role of assertiveness. Rawal Med. J. 2021, 46, 416–419. [Google Scholar]

- Korem, A.; Horenczyk, G.; Tatar, M. Inter-group and intra-group assertiveness: Adolescents’ social skills following cultural transition. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrocal-Izquierdo, N.; Bernardo, M. Esquizofrenia y enfermedad cerebrovascular. Descripción de una serie y revisión bibliográfica. Actas Españolas Psiquiatr. 2014, 42, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A.H.Y.; Potash, J.S.; Fong, T.C.T.; Ho, V.F.L.; Chen, E.Y.H.; Lau, R.H.W.; Ho, R.T.H. Psychometric properties of a Chinese version of the Stigma Scale: Examining the complex experience of stigma and its relationship with self-esteem and depression among people living with mental illness in Hong Kong. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casados, A.T. Reducing the Stigma of Mental Illness: Current Approaches and Future Directions. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2017, 24, 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defar, S.; Abraham, Y.; Reta, Y.; Deribe, B.; Jisso, M.; Yeheyis, T.; Ayalew, M. Health related quality of life among people with mental illness: The role of socio-clinical characteristics and level of functional disability. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1134032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saavedra, J.; Brzeska, J.; Matías-García, J.A.; Arias-Sánchez, S. Quality of life and psychiatric distress in people with serious mental illness, the role of personal recovery. Psychol. Psychoter. Theory Res. Pract. 2023, 96, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, M.; Bosia, M.; Baraldi, M.; Bechi, M.; Spangaro, M.; Cocchi, F.; Cavallaro, R. Achieving recovery in patients with schizophrenia through psychosocial interventions: A retrospective study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernea, M.; Neagu, A.; Georgescu, M.; Modan, A.; Zaulet, D.; Hirit Alina, C.; Stan, V. Promoting the resilient process for deaf children by play and drama therapy. In Proceedings of the Second World Congress on Resilience: From Person to Society, Timisoara, Romania, 8–10 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.D. Playing with madness: Developmental Transformations and the treatment of schizophrenia. Arts Psychother. 2012, 39, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson-Ohayon, I.; Mashiach-Eizenberg, M.; Lavi-Rotenberg, A.; Roe, D. Randomized Controlled Trial of Adjunctive Social Cognition and Interaction Training, Adjunctive Therapeutic Alliance Focused Therapy, and Treatment as Usual Among Persons With Serious Mental Illness. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schön, U.K.; Denhov, A.; Topor, A. Social Relationships as a Decisive Factor in Recovering from Severe Mental Illness. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2009, 55, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Sayama, H. Mental disorder recovery correlated with centralities and interactions on an online social network. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drapalski, A.L.; Tonge, N.; Muralidharan, A.; Brown, C.H.; Lucksted, A. Even mild internalized stigma merits attention among adults with serious mental illness. Psychol. Serv. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielańska, A.; Cechnicki, A. Drama therapy in a community treatment programme. In Therapeutic Communities for Psychosis: Philosophy, History and Clinical Practice; Gale, J., Realpe, A., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 224–229. [Google Scholar]

- Greg, P. The operational components of drama therapy. J. Group Psychother. Psychodrama Sociom. 1992, 45, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Feniger-Schaal, R. A dramatherapy case study with a young man who has dual diagnosis of intellectual disability and mental health problems. Arts Psychother. 2016, 50, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, R.; Tarasova, D.; Bergmann, T.; Sappok, T. An improvisational theatre intervention in people with intellectual disabilities and mental health problems. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, J.; Brown, C.; Corrigan, D.; Goldblatt, P.; Hackett, S. Advances for future working following an online dramatherapy group for adults with intellectual disabilities and mental ill health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A service evaluation for Cumbria, Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 2022, 50, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landy, R. Role theory and role method of drama therapy. In Current Approaches in Drama Therapy; Johnson, D., Emunah, R., Eds.; Charles Thomas: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bademci, H.O.; Karaday, E.F.; Zulueta, F. Attachment intervention through peer-based interaction: Working with Istanbul’s street boys in a university setting. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 49, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, J.; Andersen-Warren, M.; Hackett, S. A systematic review to investigate dramatherapy group work with working age adults who have a mental health problem. Arts Psychother. 2018, 61, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melero Aguilar, N. El paradigma crítico y los aportes de la investigación acción participativa en la transformación de la realidad social: Un análisis desde las ciencias sociales. Cuest. Pedagógicas 2012, 21, 339–355. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Chaves, V.E. El Estudio de Caso y su Implementación en la Investigación. Rev. Int. Investig. Cienc. Soc. 2012, 8, 141–150. Available online: http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3999526 (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Souza, F.; Souza, D.; Costa, A. Investigação Qualitativa: Inovação, Dilemas e Desafíos; Ed. Ludomedia: Aveiro, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Royse, D.; Thyer, B.; Padgett, D. Program Evaluation. An Introduction to an Evidence-Based Approach, 6th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Aguayo, S.; Pino-Juste, M. Drama therapy and theater as an intervention tool: Bibliometric analysis of programs based on drama therapy and theater. Arts Psychother. 2018, 59, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajnani, N. Reflection-in-action: An argument for arts-based practice as research in drama therapy. In Through the Looking Glass: Dimensions of Reflection in the Arts Therapies; Hougham, R., Pitruzzella, S., Scoble, S., Eds.; University of Plymouth Press: Devon, UK, 2015; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P. Three challenges for drama therapy research: Keynote NADTA conference, Montreal 2013. Drama Ther. Rev. 2015, 1, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.; Rozenberg, M.; Powell, M.; Honce, J.; Bronstein, L.; Gingras, G.; Han, E. A step toward empirical evidence: Operationalizing and uncovering drama therapy change processes. Arts Psychother. 2016, 46, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J. Cuestionario de Salud SF-36 y Cuestionario de Salud SF-12. BiblioPRO; Instituto Municipal de Investigaciones Médicas: Barcelona, Spain, 1996; Available online: https://bibliopro.org/buscador/663/cuestionario-de-salud-sf-12 (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Carrasco, I.; Clemente, M.; Llavona, L. Análisis del inventario de aserción de Gambrill y Richey. Estud. Psicol. 1989, 37, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Anguera, E.; Prat, G.; Vilamala, S.; Escandell, M.; García-Franco, M.; Martin, J.; Ochoa, S. Validación de la versión española del inventario de asertividad Gambrill y Richey en población con diagnóstico de esquizofrenia. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pino-Juste, M. La evaluación de los aprendizajes. In Diseño y Desarrollo del Currículum; Cantón, I., Pino-Juste, M., Eds.; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- Crook, R.A. A Drama Therapy Program for Sexually Traumatized School-Age Children with Dissociative Characteristics. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of the Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tevelev, V. Fairy tale group therapy: A cognitive-behavioral group therapy program by means of drama-therapy for children with disruptive behavior disorders. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2012, 49, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, J. An evaluative account of the working of a dramatherapy peer support group within a comprehensive school. Support Learn. 1991, 6, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliaz, E.; Flashman, A. Road signs: Elements of transference in drama therapy: Case study. Arts Psychother. 1994, 21, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haste, E.; McKenna, P. Clinical effectiveness of dramatherapy in the recovery from severe neuro-trauma. In Drama as Therapy Volume 2: Clinical Work and Research into Practice; Jones, P., Ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlyn, P. Drama therapy for persons with intellectual disability in Singapore: Review of a 3-month program. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2009, 6, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, J.M. The Effects of A Program of Drama Therapy on the Social Skills Behaviors of Institutionalized Mentally Retarded Adults. Ph.D. Thesis, Pittsburgh University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- James, M.; Johnson, D.R. Drama therapy in the treatment of combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Arts Psychother. 1996, 23, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towers, T. An Examination of the Challenges of Veteran Reintegration and the Application of Drama Therapy Techniques. Ph.D. Thesis, Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cyr, D.P. Spirit in Motion: Developing a Spiritual Practice in Drama Therapy; California Institute of Integral Studies: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Castaños, S.; Reyes, I.; Rivera, S.; Díaz, R. Estandarización del Inventario de Asertividad de Gabmbrill y Richey-II. Rev. Iberoam. Diagnóstico Evaluación Avaliação Psicológica 2011, 29, 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jakovljević, M. Creativity, Mental Disorders and their Treatment: Recovery-Oriented Psychopharmacotherapy. Psychiatr. Danub. 2013, 25, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rippon, D.; Shepherd, J.; Wakefield, S.; Lee, A.; Pollet, T.V. The role of self-efficacy and self-esteem in mediating positive associations between functional social support and psychological wellbeing in people with a mental health diagnosis. J. Ment. Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Beirne, L. Creating community connections and reconstituting self in the face of psychiatric disability. Int. J. Interdiscip. Soc. Sci. 2010, 5, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.H.; Murnan, J. Research Limitations and the Necessity of Reporting Them. Am. J. Health Educ. 2004, 35, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).