Sustainable Cities, Smart Investments: A Characterization of “A Thousand Days-San Miguel”, a Program for Vulnerable Early Childhood in Argentina

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mil Días-SM in the Regional and National Context

2.1. Previous Similar Programs in Latin America

2.2. Previous Similar Programs in Argentina

3. The Context of Policy Making in Argentina

- (1)

- Organizational capacity, which refers to the concordance between the goals of the organization and the resources, processes, and infrastructure it has.

- (2)

- Budgetary capacity, which refers to the amount and autonomy to administer the budget.

- (3)

- Civil service capacity, which refers to the technical characteristics of the civil service, training and stability.

- (4)

- Ability to reach, which refers to the ability to reach the target audience in the territory and overcome resistance by organized groups.

- (5)

- Political capacity, which refers to both the construction of power and recognition of other agencies of equal hierarchy within the public administration (horizontal political capacity), as well as of authorities superior to those of the agency (vertical political capacity).

4. Data and Methodology

5. Mil Días-SM Program’s Design and Implementation

5.1. The Coordination of Early Childhood, Childhood, and Family (CPINF)

5.2. Motivation, Target Population, Intervention Instruments and Goals

5.3. Legal Framework

- The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) (of constitutional status in Argentina since 1994).

- National Law No. 26,061, on the Comprehensive Protection of the Rights of Boys, Girls and Adolescents (2005).

- National Law No. 26,233, for the Promotion and Regulation of Child Development Centers (2007)

- National Law No. 26,485, on Comprehensive Protection to prevent, punish and eradicate violence against women and its Regulatory Decree No. 1011/10 (2009).

- Buenos Aires Provincial Law No. 12,569, on Family Violence and its Regulatory Decree 2875/05 (2000).

- Buenos Aires Provincial Law No. 13,298, for the Promotion and Comprehensive Protection of Children’s Rights (2005).

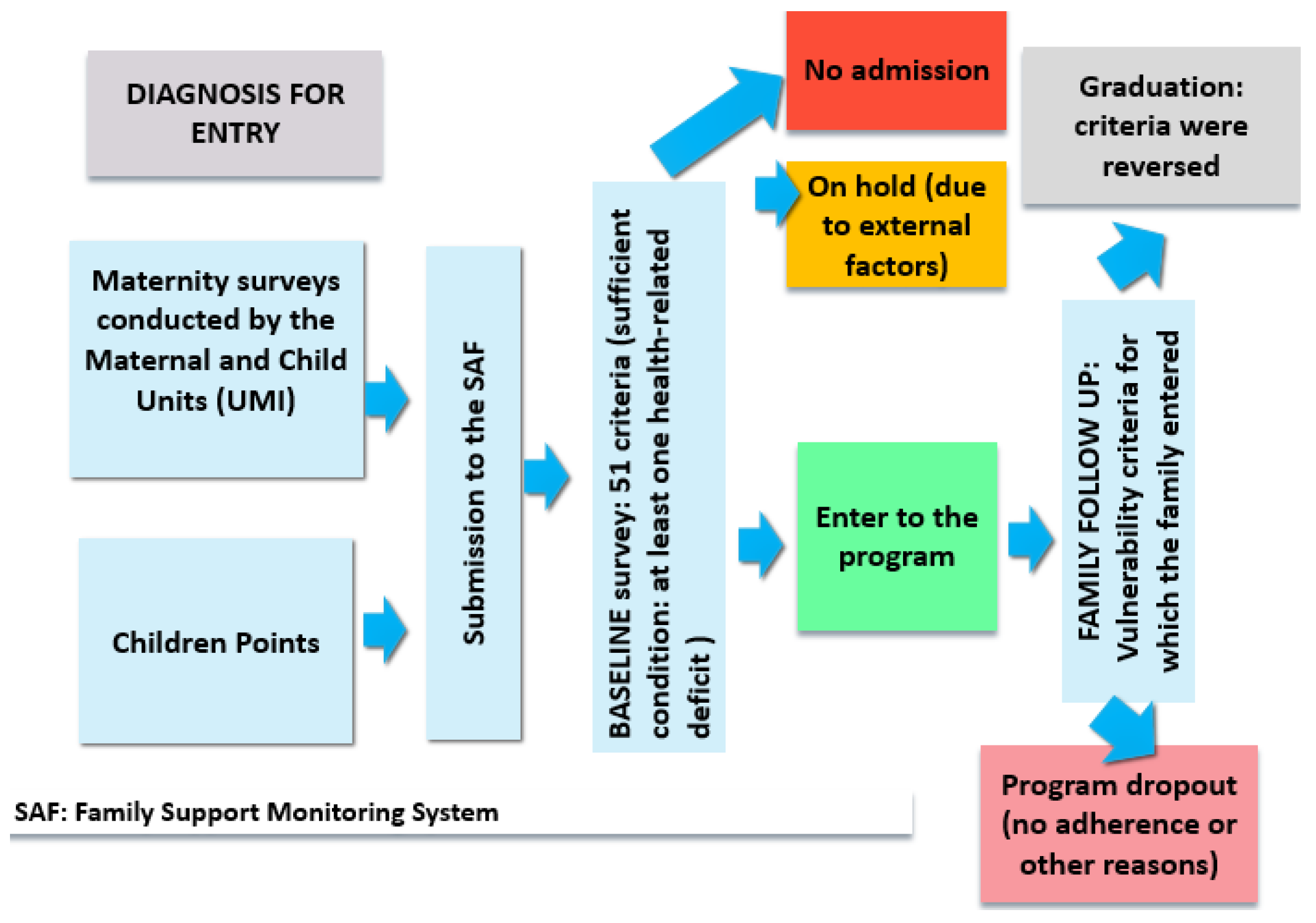

5.4. The Program’s Circuit

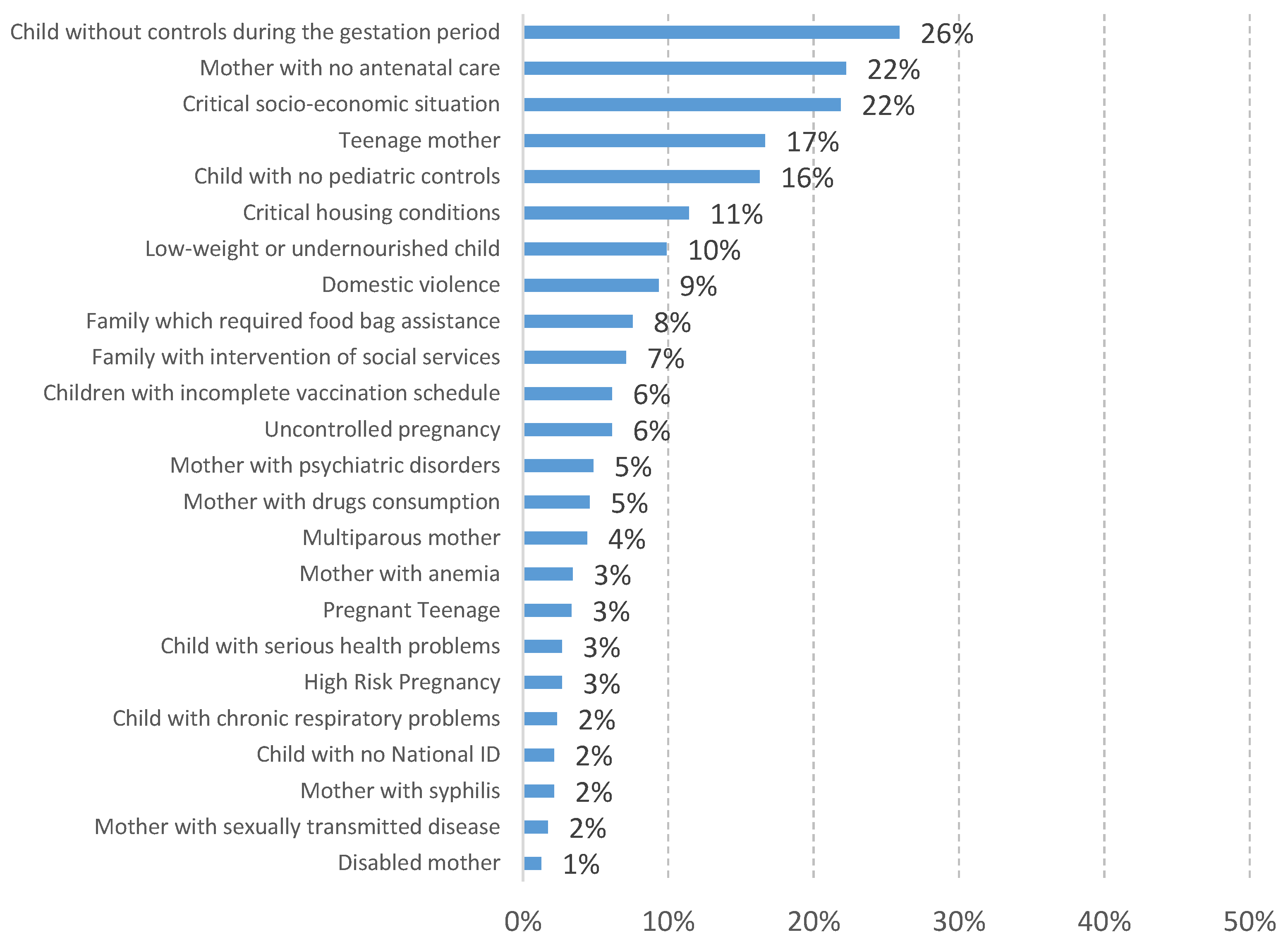

5.5. Entrance Vulnerability Criteria to the Program

5.6. Operationalization of the Program

5.6.1. The Program’s Coordination Team

- Train the family companions so that they broaden their knowledge and can provide new tools to the families they mentor.

- Monitor and guarantee that family companions comply with the required tasks with each family (Table A1) and the established timeline.

- Supervise and support the work of family companions. Clarify doubts, concerns or questions that arise during the mentoring process.

- Bring together the different parts involved in the program (CDIFs, CAPS’ social workers, schools, the hospital’s social services, family companions) to think, plan and coordinate joint intervention strategies.

- Visit the families that require a specific intervention and follow-up in some area (nutrition, children’s play, development and bonding, education), complementing the work of the family companions.

5.6.2. The Program’s Companion Team and Its Work

“We started at these 4 points [Mitre, Santa Brígida, Obligado and San Ambrosio neighborhoods], we started with four family companions (…). Little by little we trained them, trying to emphasize what they had to observe and how they had to mentor these families. (…) as new families were incorporated into the program (…) the team grew, they worked and strengthened much more, and today we have reached [a team of] 16 companions. It cost us a lot.”(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

“As the program grew (…) the profile changed. (…) we started looking for companion’s profiles that were social, nursing or health-related. Now we have a wide range. A nice team was put together. But it cost a lot. When we started, the companions were just observers, but over time, as they became professionals working in the territory, their role changed, and they began to intervene. The pairs of companions are intended to complement each other, for example, someone from social work and someone from health.”(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

“We designed the trainings based on all the entrance criteria. We try that at least once the companions have had a training day on each of these topics. (…) There are many respiratory diseases in the winter, we have many cases of syphilis, so we have trainings on these issues. There is also a lot of malnutrition.” […] Here we must take advantage of all the resources we have. San Miguel is incredible for the [human] resources it has, and they can be coordinated very well. We take advantage of the little things; we make the most of them. For example, Gender Policies offers training sessions, so the companions take advantage of those sessions.”(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

“The truth is that at first it was very difficult. The program was known by word of mouth. Now families already know it. At first, they were afraid of us: ‘the social workers are going to take our children away from us!’, it was the first thing that mothers thought. It was very hard work and with some families it is harder than with others.”(Director of the DPPPI, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

“What the mothers are most grateful for is the bond [they developed with the family companions], because they are very lonely women. (…). Even when the family companions are professionals, their contribution is much more from the human side. Maybe a hug, or “I will book you an appointment”, or “get some rest”, that’s very important and highly valued. That invisible job. It is much more than mentoring.”(Director of the DPPPI, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

5.6.3. Complementary Interventions

“I also wanted to tell you about the food box, (…) it is explained to the families that they will receive the food box [only] while they are in the program. So the families say: “and then, what are we going to do?” (…) We have to be facilitators and at the same time give the tools (…). If you always help, you are actually hurting them (…). With the food box we work on that too.(Director of the DPPPI, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

So “…we help them to access the “Mas Vida” benefit, which gives you a benefit for each child, a card with money. The mothers say: “but the box is better”, and we tell them: (…) “We give you the tools so that you learn to buy varied and nutritious food for your children. The box is no better.””(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

6. Mil Días-SM Program’s Descriptive Analysis from a Quantitative and Qualitative Approach

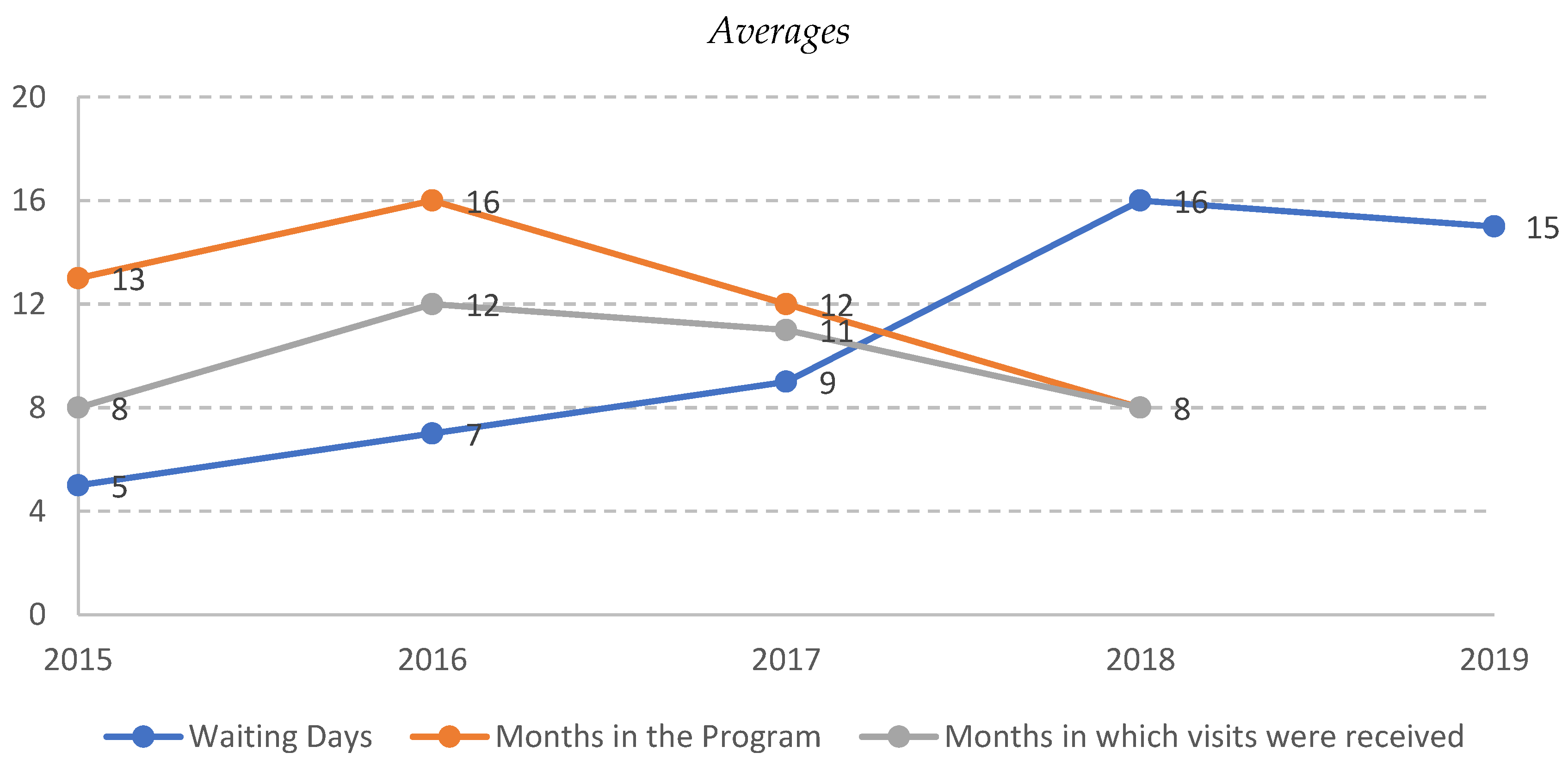

6.1. Program’s Scale, Entrance Waiting Time and Average Time in Program

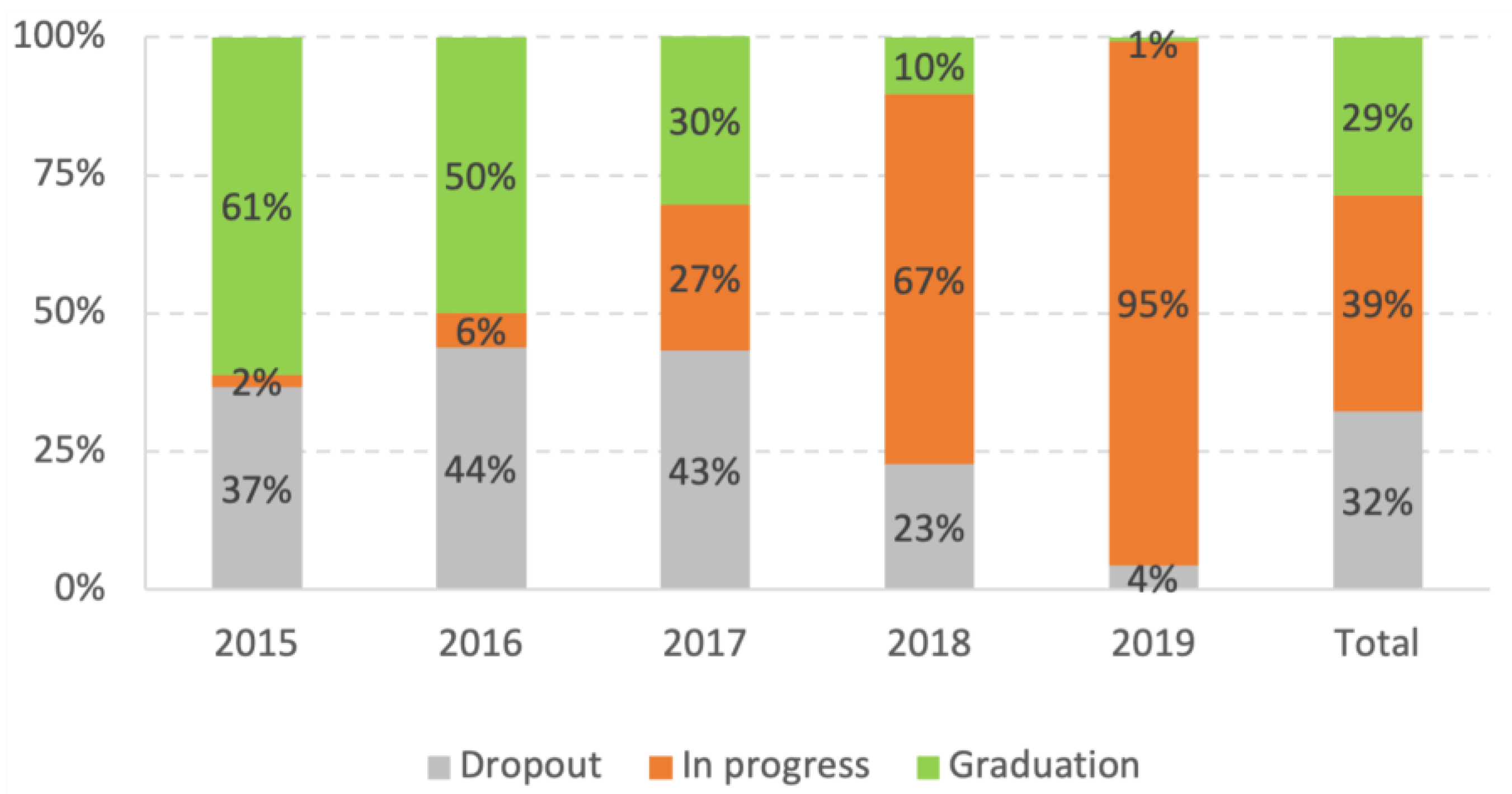

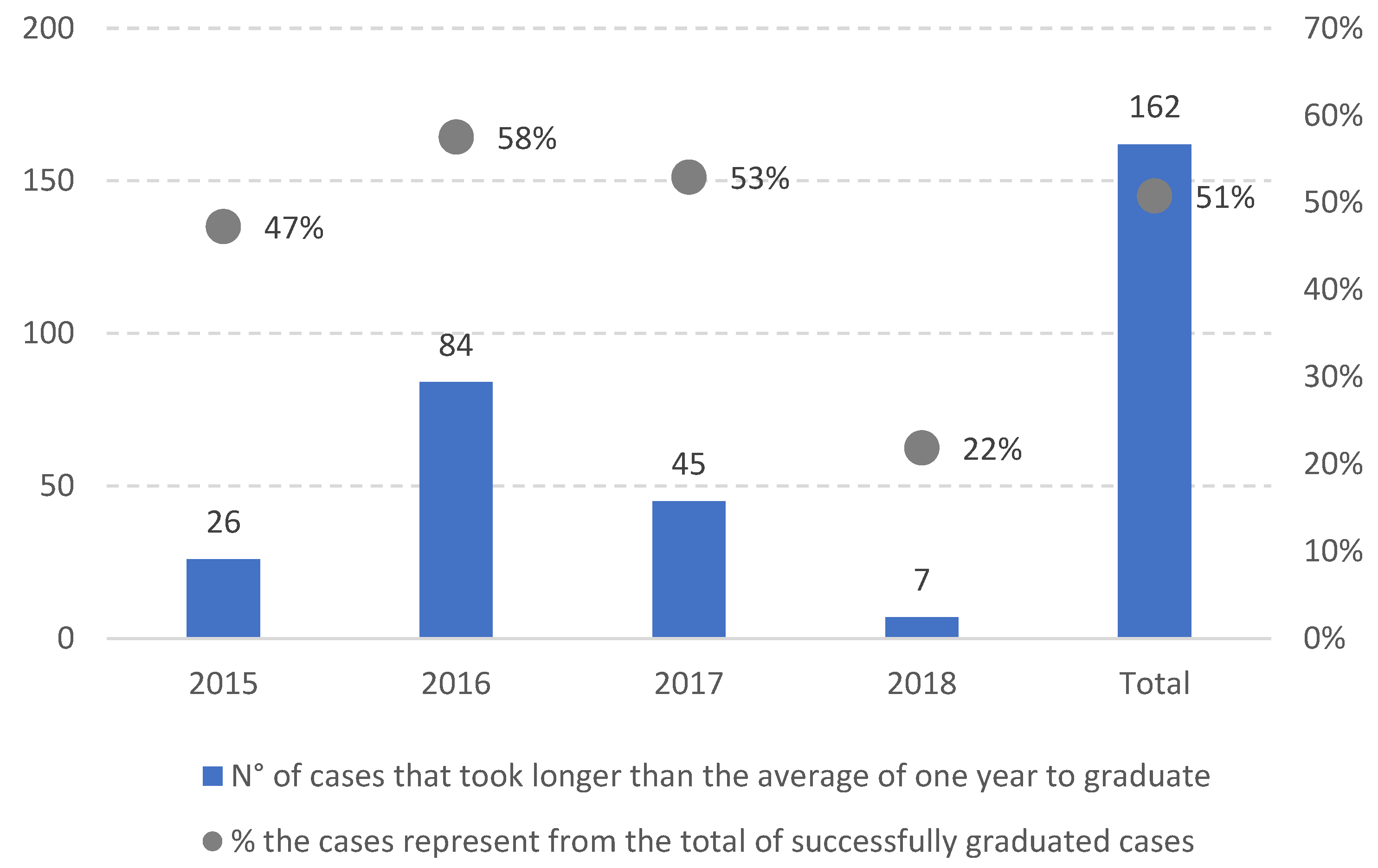

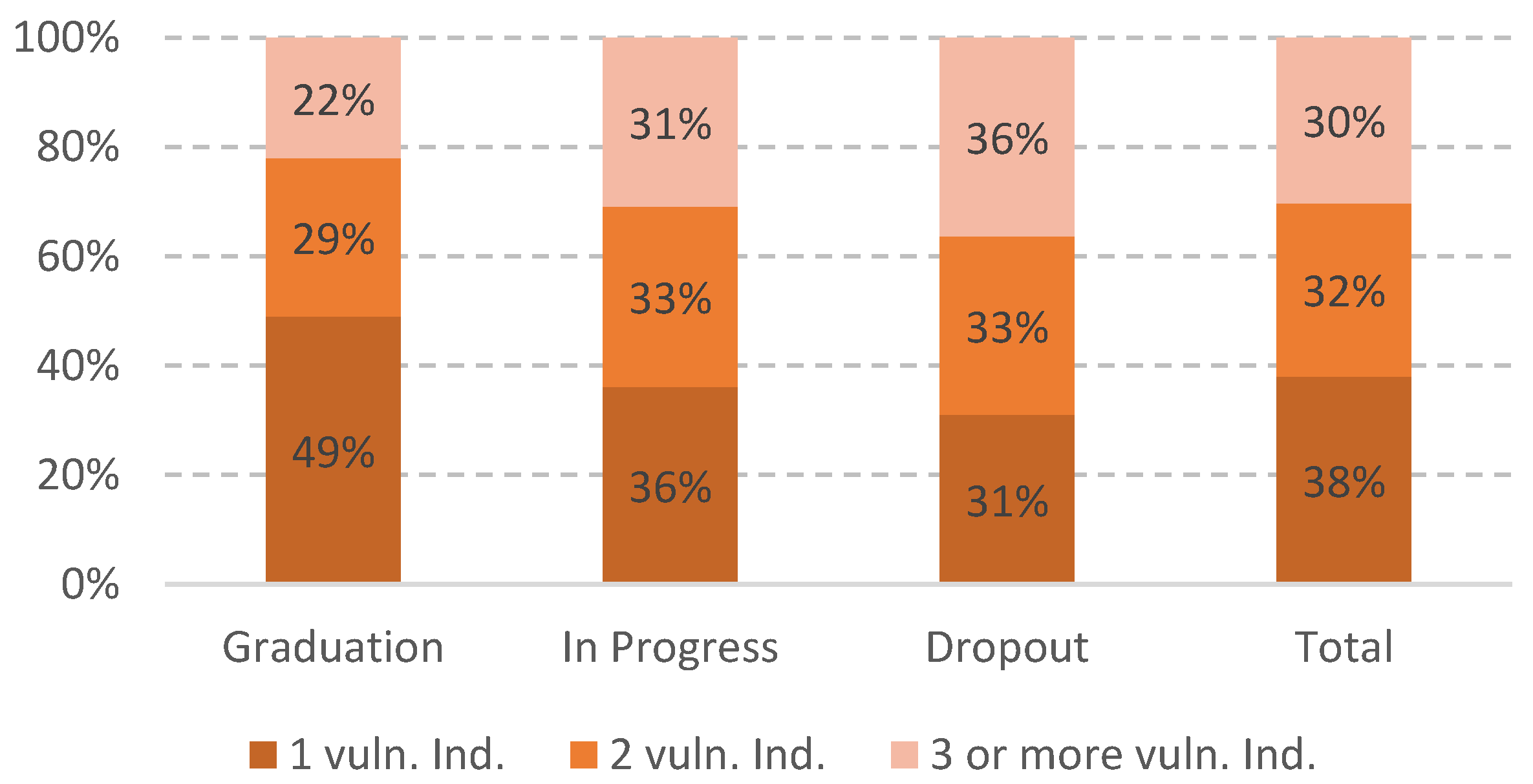

6.2. Dropout Rate and Excess Time to Graduation

“At first when we thought about the program, we thought it would last 10 months, but the reality is different. The pregnant woman had her baby, she was going to be released, but she got pregnant again. It happens. We stand by them. When the criteria are reversed, this mother who did not have pregnancy controls, did not take her little ones to the health checkups, her children did not have the national ID… Now they have a very good bond with the health center, they go to the hospital, that little boy entered the CDIF (…), she bonds well with her baby. That is, we release only when all the admission criteria have been reversed. Thus, we have families since the beginning or the program, they are very few, but we have everything.”(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

6.3. Entrance Criteria and Time in Program

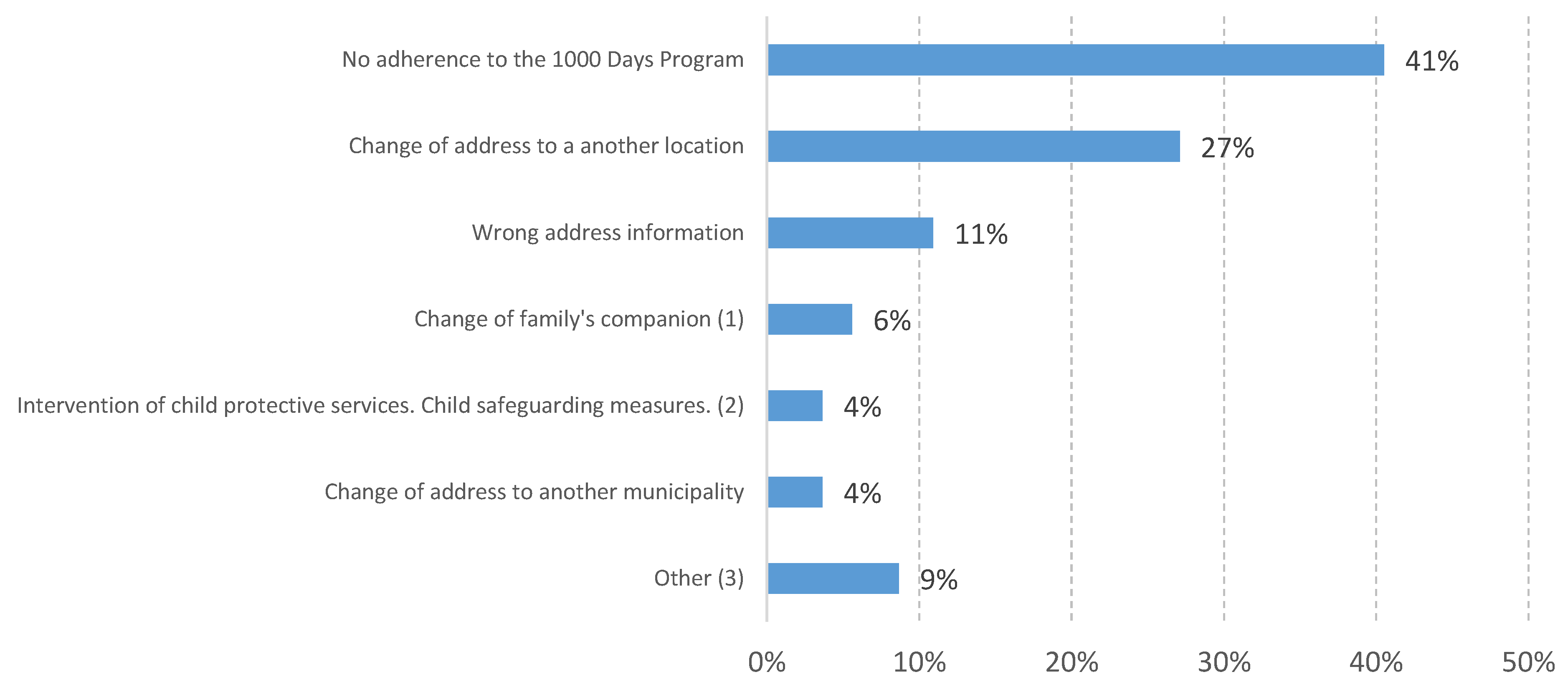

6.4. Dropout Reasons

“There are people not interested in being in the program and we cannot force them. We have various reasons [for program dropout], a lot due to ignorance of the program, fear, and yes, sometimes there are situations of extreme family violence, there is control by someone else who tells [the woman] ‘don’t even think about opening your mouth’. Think that tools are given to those mothers. That’s what gives them the chance to get out.”(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

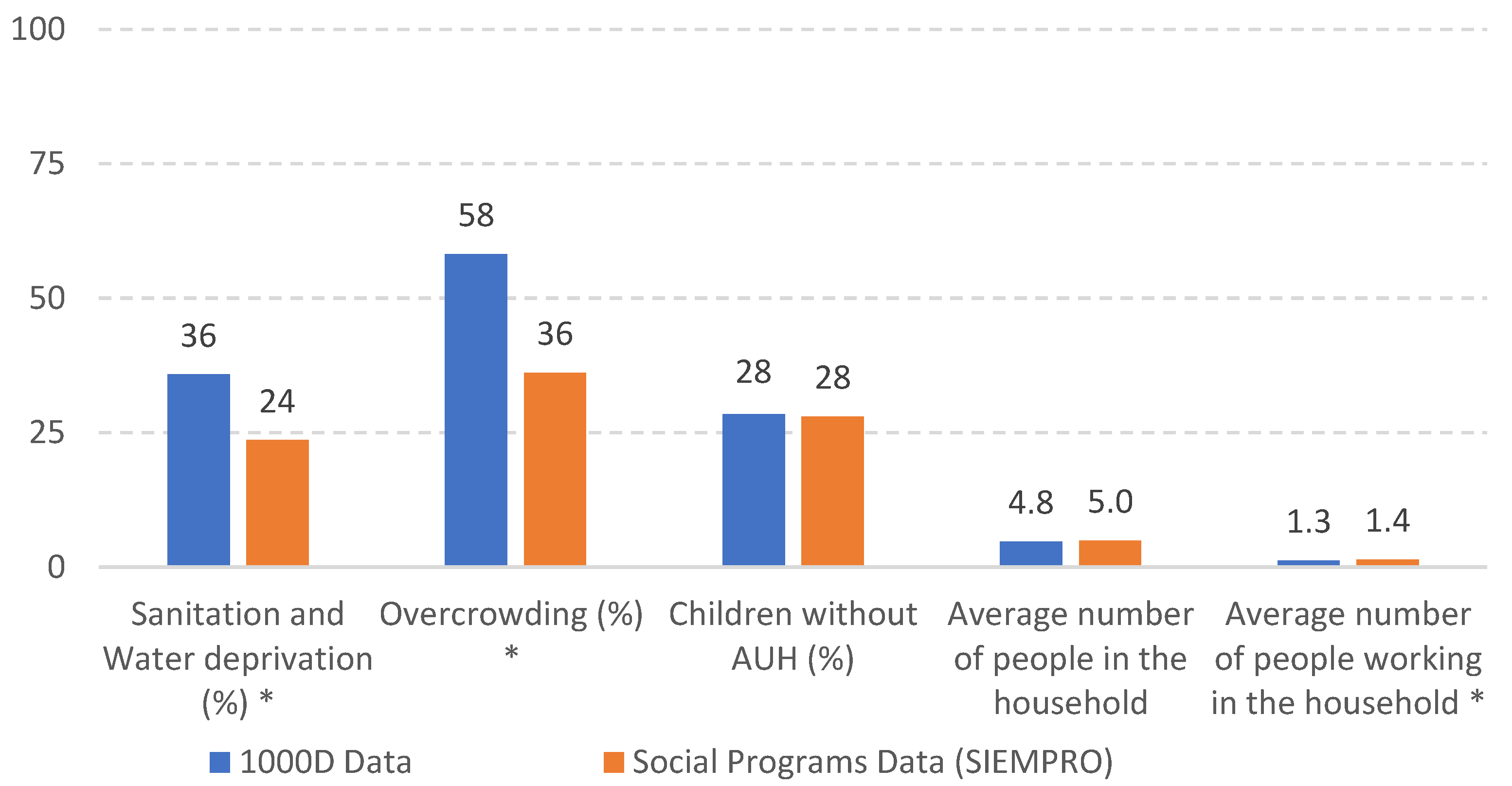

6.5. Beneficiaries’ Housing and Basic Services Deprivations

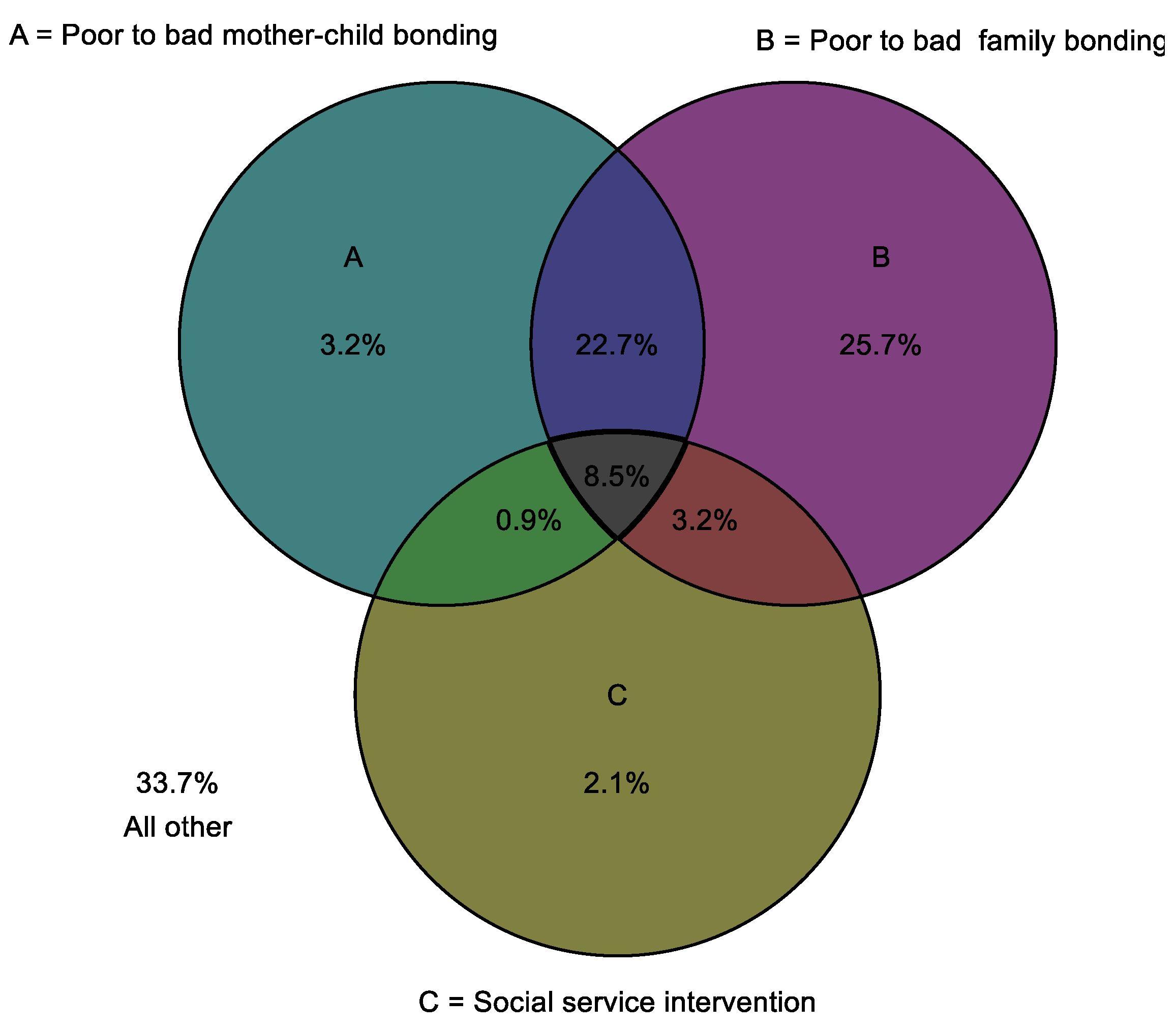

6.6. Beneficiaries’ Home Environment and Maternal Bonding

“It costs a lot, there is a lot of violence, many cases of abuse that are very entrenched and accepted. (…) You have no idea… until you are in there. There are situations of extreme family violence. We even had a [human] trafficking situation. At that level. (…) you uncover situations (…) that’s where the technical team has a lot of work. There is where we reinforce the visits.”(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

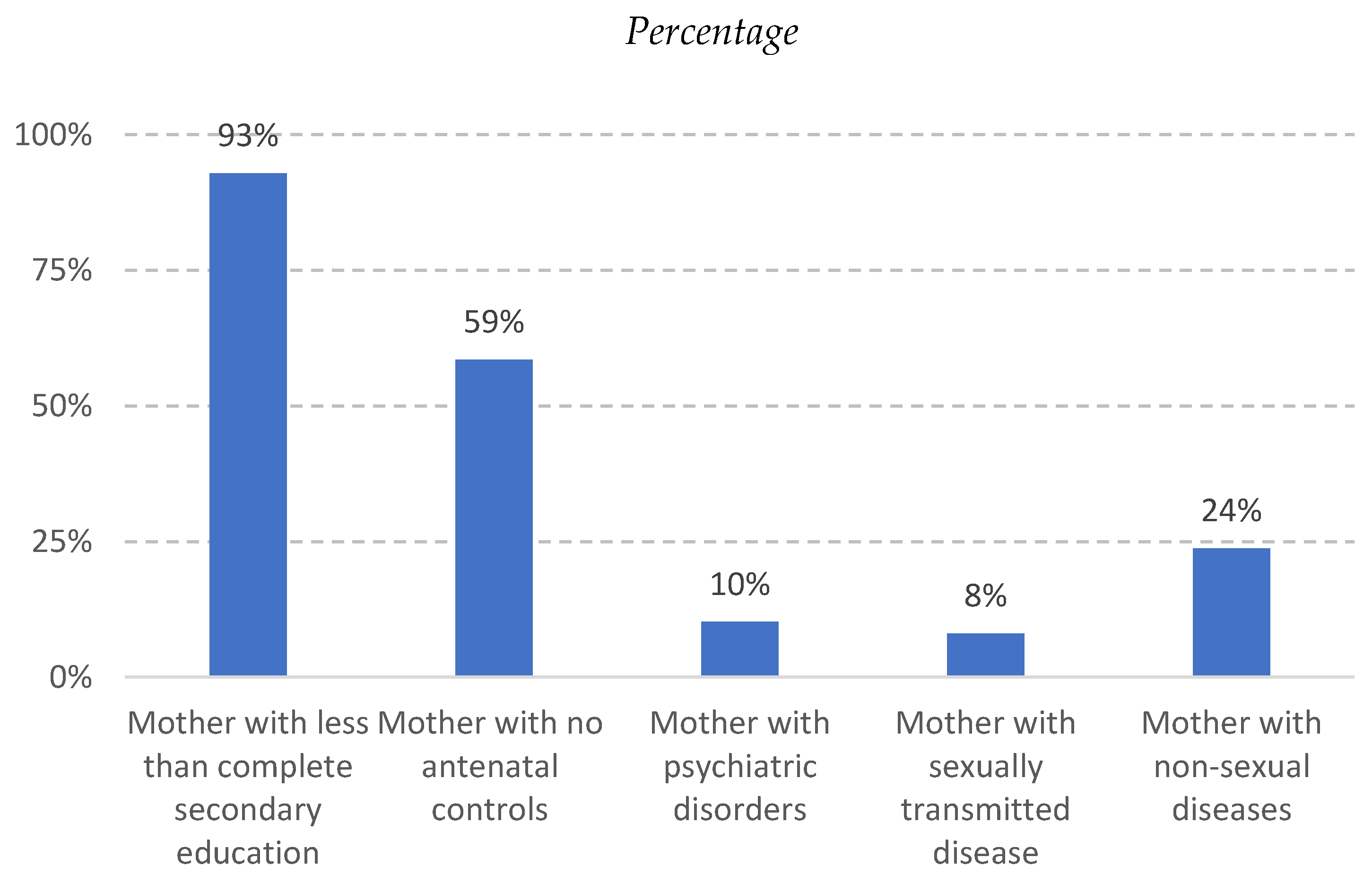

6.7. Mothers’ Characteristics

“There is a mother [referring in general to mothers] who did not finish high school and so on, we work on her life project (…). Sometimes it’s finishing primary school, something so basic. It is a project for them (…) There is a mother in Barrufaldi that participated in the program, and is finishing high school, she has completed a kitchen assistant course and has also started working in the CDIF as a cook. These are impressive achievements in her case.”(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

“In 2014 we started making a diagnosis by interviewing the women who attended the perinatal area of the Larcade hospital. It was detected that there were many mothers who did not undergo check-ups during pregnancy and came to have their baby with very few or no check-ups at all, for different reasons… they had young children and could not attend the health center, or they had not come due to situations of violence; there was a wide variety of reasons.”(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

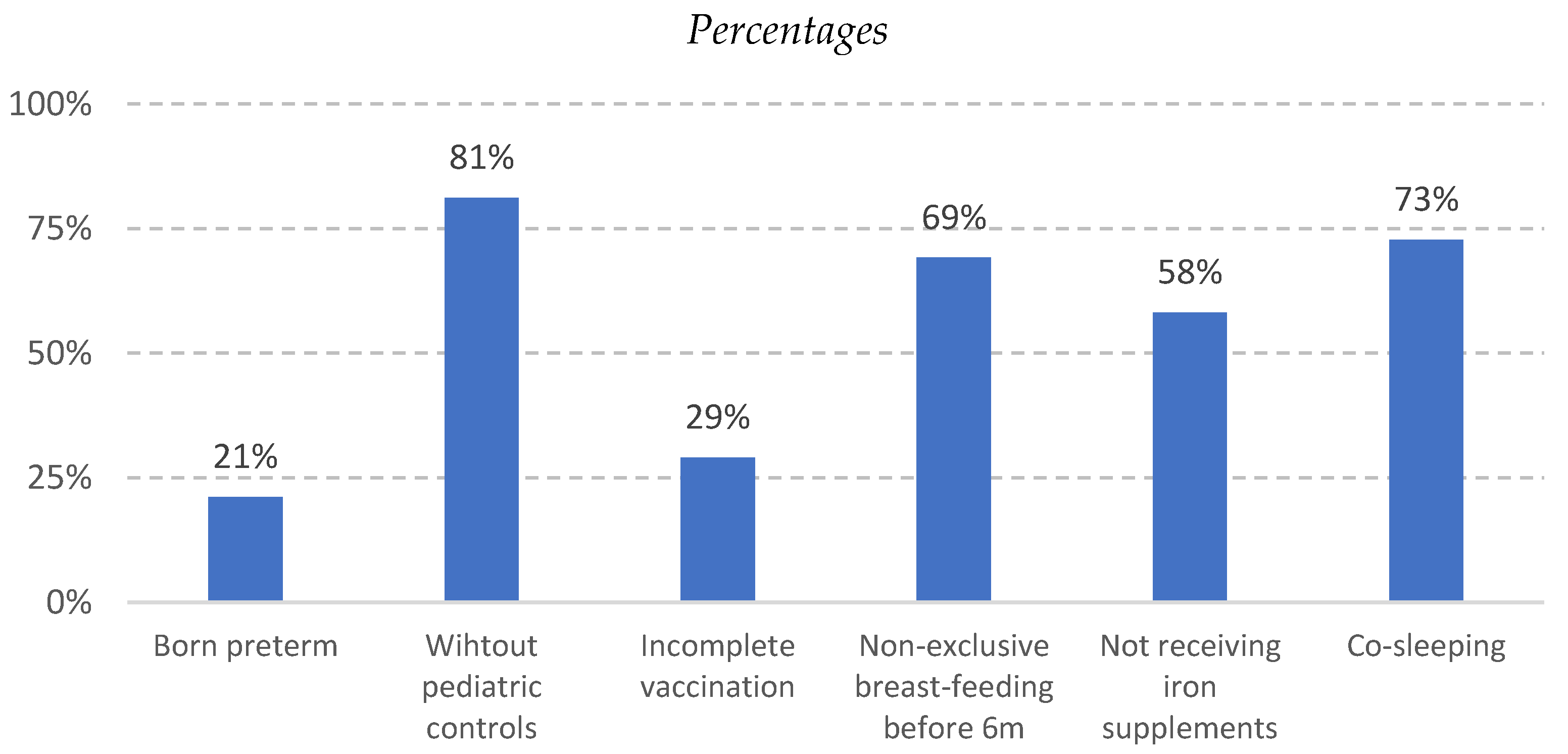

6.8. Children’s Characteristics

“We go to the houses (…) The social worker is faced with an incredibly complex panorama. We have a technical team that supervises and mentors. I always say: “let’s focus on our entry criteria”. We can’t fix everything. We prioritize that the little one does the [health’s] controls.”(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

“The mentoring [of the program] stands out as an opportunity to learn issues related to care. In the interviews, the women refer to “things they did not know” regarding food, breast-feeding, cleanliness, water maintenance and symptoms of respiratory diseases, among others.”[48]

7. Concluding Remarks

“This is a public policy where the results will be seen 20 years from now… that is our project, that this boy grows up healthy, that he finishes secondary school, that he goes to university… because his mother accessed other resources and she could transmit… that’s why I say that the results reach the whole family (…) At the beginning, from outside, they told us: “You are crazy, (…) in a year everything will fall apart”. Well, let’s try at least… We were very hard-headed at that time (…). And here we are. There’s a lot to go but we’re on our way.”(Mil Días-SM program’s GC, personal communication, 8 August 2018)

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Type | Criterion | Tasks Assigned by Entrance Criterion |

|---|---|---|

| Health | 1. Children with no antenatal controls 2. Children without pediatric controls | Guarantee the corresponding pediatric controls. Refer to the corresponding health areas (CAPS, Hospital or specialists if needed), facilitate the booking of appointments, guarantee that program participants are given priority. |

| 3. Children with low weight/undernutrition | Confirm that he/she has received health care. Confirm he/she has and is taking the iron supplement. Book appointments with pediatrician at the home’s closest CAPS Refer to nutritionist. | |

| 4. Children with incomplete vaccination schedule | Confirm he/she has complied with the vaccination schedule. Otherwise coordinate with CAPS to ensure that he/she receives the missing vaccines. | |

| 5. Children with anaemia | Confirm that he/she has received health care. Confirm he/she has and is taking the iron supplement. Verify he/she has completed all the pediatric controls (every month until the first year of life). Observe whether there are personal or family risk factors (housing, school meals, family income). Encourage exclusive breast-feeding at least until 6th months of age. | |

| 6. Children with crhonic respiratory diseases | Request a housing-conditions report to the Secretariat of Human and Social Development. Guarantee health control and access to inhalers (if necessary). Guarantee health control with a pneumonologist at least twice a year. | |

| 7. Children with syphilis | Refer to the corresponding health specialist (pediatric dermatologist and/or pediatric urologist). Guarantee the monthly pediatric control. Guarantee he/she is taking the prescribed medicines. | |

| 8. Children with HIV | Refer to the corresponding health specialist. Guarantee health checkups. | |

| 9. Children with brain damage | Refer to the corresponding health specialists (stimulation, psychomotricity, neurology). Guarantee the monthly pediatric control. Guarantee he/she is taking the prescribed medicines (if applicable). | |

| 10. Children with heart disease | Refer to the corresponding health specialist. Guarantee cardiological control. Guarantee he/she is taking the prescribed medicines (if applicable) | |

| 11. Children or families with tuberculosis 12. Mother or family with tuberculosis 13. Pregnant women or families with tuberculosis | Confirm that a TB screening test has been conducted to all household members. Enter the child, mother or pregnant woman into the municipal TB program. Guarantee the monthly health checkups. Guarantee he/she is taking the prescribed medicines | |

| 14. Adolescent mothers | Guarantee the monthly health checkups of mother and children. | |

| 15. Mothers with low weight | Do the health checkups and blood tests. | |

| 16. Mothers with epilepsy | Refer to the corresponding municipal program for specialized support. Verify that the health checkups with the corresponding specialist are being done. | |

| 17. Multiparous mothers | Refer to the Family Planning area for advice and support. | |

| 18. Mothers with heart disease | Book an appointment with a cardiologist. | |

| 19. Mothers with anemia | Confirm he/she has and is taking the iron supplement. | |

| 20. Mothers with HIV 21. Mothers with syphilis 22. Mothers with Chagas disease | Refer to the corresponding specialist. Guarantee the health checkups. Guarantee she is taking the prescribed medicines | |

| 23. Mothers with sexually transmitted diseases | Guarantee she is doing the corresponding health checkups. | |

| 24. Mothers with neurological problems | Guarantee the health and neurological examination. | |

| 25. Mothers with chronic diabetes | Guarantee she is doing the health checkups. Guarantee she is taking the prescribed medicines. | |

| 26. Mothers with drug addiction 27. Mothers with psychiatric problems 28. Pregnant women with drug addiction 29. Pregnant women with psychiatric problems | Guarantee she is doing the health checkups. Refer to Municipal Mental Health Center | |

| 30. Mothers without no antenatal control | Give a closure to the pregnancy medical history. Refer to the corresponding health areas (CAPS, Hospital or specialists if needed), facilitate the booking of appointments, guarantee that the program participants are given priority. | |

| 31. Mothers with disabilties | Guarantee health checkups for mother and child. Refer to the corresponding specialized area if necessary. Refer to a neurologist or physiatrist if necessary. | |

| 32. Mothers with children with no national ID 33. Mothers with no national ID 34. Pregnant woman with no national ID | Refer to the National Register Office, or to the mobile offices periodically implemented by the municipality in which people can obtain their national ID without the need to book an appointment. | |

| 35. Families with intervention of social services * 36. Mothers with conflicts with the law 37. Pregnant women with conflicts with the law | Coordinate the support and intervention with CAPS’ social worker. Submit an admission report to the social services Check the family’s record and meet with the social services’ intervening team to work jointly | |

| 38. Pregnant women with anemia | Confirm she has and is taking the iron supplement. | |

| 39. Pregnant women with neurological problems | Guarantee she is taking the prescribed medicines. Guarantee neurological examination. Follow up of medical examinations, find out a diagnosis, check whether she has or needs a national certificate of disability (which enables several benefits). | |

| 40. Teenage pregnancy 41. Pregnant women with no antenatal care 42. Women with a risky pregnancy | Guarantee antenatal care. Refer to the corresponding health areas (CAPS, Hospital or specialists if needed), facilitate the booking of appointments, guarantee that program participants are given priority. | |

| 43. Pregnant women with diabetes 44. Pregnant women with heart diseases 45. Pregnant women or mothers with hypertension | Guarantee antenatal care and health checkups Guarantee she is taking the prescribed medicines. | |

| 46. Pregnant women with disabilities | Guarantee antenatal care and health checkups Refer to the Disability area. | |

| Housing and socio-economic | 47. Critical housing condition | Request a housing-conditions report to the social worker from the Secretariat of Human and Social Development. Ensure the housing-conditions report is received by the area of critical assistance. Guarantee pediatric controls for children. |

| 48. Critical socio-economic situation (no household member is working) | Refer to the municipal employment office, ANSES and Social Development (national administrative offices). Guarantee pediatric checkups. | |

| Family violence | 49. Family violence | Refer to the Gender Policy Office. Follow protocol for males with violent behavior. |

| 50. Child abuse * | Refer to social services. | |

| Housing and socio-economic | 51. Family in vulnerability situation (undernutrition and no household member is working) | Refer to the municipal employment office, ANSES and Social Development (national administrative offices). Guarantee pediatric controls. Refer to nutritionist. |

References

- Heckman, J.J. Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science 2006, 312, 1900–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2014. Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, M.C.; Boo, F.L. Invertir en los Primeros Años de vida: Una Prioridad para el BID y los Países de América Latina y el Caribe; 2010. Nota Técnica División de la Protección Social y Salud N°188. Washington: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID). Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/viewer/Invertir-en-los-primeros-a%C3%B1os-de-vida-Una-prioridad-para-el-BID-y-los-pa%C3%ADses-de-Am%C3%A9rica-Latina-y-el-Caribe.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Heckman, J.J. The economics, technology, and neuroscience of human capability formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 13250–13255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.B.; Riis, J.L.; Noble, K. State of the Art Review: Poverty and the Developing Brain. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shonkoff, J.; Boyce, W.T.; McEwen, B. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 301, 2252–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariana, P.; Naveed, A. Health. In An Introduction to the Human Development and Capability Approach: Freedom and Agency, 1st ed.; Deneulin, S., Shahani, L., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.L.; Heckman, J.J.; Leaf, D.E.; Prados, M.J. The Life-Cycle Benefits of an Influential Early Childhood Program; CESR-Schaeffer Working Paper No. 2016-18; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlinski, S.; Schady, N. (Eds.) Los Primeros Años: El Bienestar Infantil y el Papel de las Políticas Públicas; BID: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, J. Human development and early childhood development. Special contribution. In Human Development Report 2014. Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leer, J.; Lopez-Boo, F. Assessing the quality of home visit parenting programs in Latin America and the Caribbean. Early Child Dev. Care 2018, 189, 2183–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakaki, A. Hacia una serie de pobreza por ingresos de largo plazo. El problema de la canasta. Real. Económica 2018, 316, 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini, L.; Tornarolli, L.; Gluzman, P. El Desafío de la Pobreza en la Argentina. Diagnóstico y Perspectivas; CIPPEC; CEDLAS; PNUD: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, J. La Pobreza en la Argentina. Explorando Más Allá de los Ingresos y Más Allá de los Promedios (Incidencia, Composición y Evolución 2004–2019, Documento de Trabajo Nro. 21, Instituto de Estudios Laborales y del Desarrollo Económico, Universidad Nacional de Salta. 2019. Available online: https://www.economicas.unsa.edu.ar/ielde/archivos/docTrabajo/WPIelde_Nro21.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2023).

- Salvia, A.; Bonfiglio, J.I.; Vera, J. La Pobreza Multidimensional en la Argentina Urbana 2010–2016. In Un Ejercicio de Aplicación de los Métodos OPHI y CONEVAL al Caso Argentino; UCA: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zack, G.; Schteingart, D.; Favata, F. Pobreza e indigencia en Argentina: Construcción de una serie completa y metodológicamente homogénea. Soc. Econ. 2020, 40, 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Poy, S.; Argentina, U.C.A.; Tuñón, I.; Sánchez, M.E.; Argentina, C.N.D.I.C.Y.T. Child Poverty in Argentina (1992–2019): Trend and Regional Disparities. Población Soc. 2021, 28, 188–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Informe temático: Pobreza Multidimensional de Niñas y Niños en Argentina. Prevalecnia, Intensidad y Factores Asociados; UNICEF: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. La Pobreza en Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes en la Argentina Reciente. Aportes Desde un Abordaje Cuantitativo y Cualitativo; UNICEF: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.E. Pobreza Multidimensional en Argentina: Evolucion, Alcances y Limitaciones de la Medición. In V Congreso Internacional “Las Caras Invisibles de la Pobreza”; Universidad Austral: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- INDEC. Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2010; INDEC: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2010.

- INDEC. Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2022. Resultados Provisionales. 2022. Available online: https://www.indec.gob.ar/ftp/cuadros/poblacion/cnphv2022_resultados_provisionales.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- INDEC. Incidencia de la Pobreza y de la Indigencia en 31 Aglomerados Urbanos; Segundo semestre de 2021; INDEC: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2021; Volume 6.

- Chudnovsky, M.; González, A.; Hallak, J.C.; Sidders, M.; Tommasi, M. Construcción de capacidades estatales Un análisis de políticas de promoción del diseño en Argentina”. Gestión Política Pública 2018, 27, 79–110. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Infancia, Adolescencia y Juventud: Oportunidades Claves Para el Desarrollo; Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia, UNICEF: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Attanasio, O.P.; Fernández, C.; Fitzsimons, E.O.; Grantham-McGregor, S.M.; Meghir, C.; Rubio-Codina, M. Using the infrastructure of a conditional cash transfer program to deliver a scalable integrated early child development program in Colombia: Cluster randomized controlled trial. Br. Med. J. 2014, 349, G5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nores, M.; Barnett, W.S. Benefits of early childhood interventions across the world: (Under) Investing in the very young. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2010, 29, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantham-McGregor, S.M.; Powell, C.A.; Walker, S.P.; Himes, J.H. Nutritional supplementation, psychosocial stimulation, and mental development of stunted children: The Jamaican Study. Lancet 1991, 338, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. Reach Up: An Early Childhood Parenting. Intervention; Epidemiology Research Unit, Caribbean Institute for Health Research: Kingston, Jamaica, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- González, M.S.; Santos, M.E. Programas de Acompañamiento Familiar en la Primera Infancia: Motivación y Diseño: El Caso del Programa Mil Días; Trabajo presentado en la Asociación Argentina de Economía Política: Working Papers 4196; Asociación Argentina de Economía Política: San Diego, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marroig, A.; Perazzo, I.; Salas, G.; Vigorito, A. Evaluación de Impacto del Programa de Acompañamiento Familiar de Uruguay Crece Contigo. Informe de Resultados; IECON Universidad de la República Convenio Oficina de Planeamiento y Presupuesto-Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y de Administración; Universidad de la República: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abramovsky, L.; Attanasio, O.; Barron, K.; Carneiro, P.; Stoye, G. Challenges to Promoting Social Inclusion of the Extreme Poor: Evidence from a Large-Scale Experiment in Colombia. Economia 2016, 2016 16, 89–141. [Google Scholar]

- Acuña, C. Los Desafíos de la Coordinación y la Integralidad para las Políticas y la Gestión Pública en América Latina, Jefatura de Gabinete de Minis-tros—Proyecto de Modernización del Estado; Mimeo: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Repetto, F. Gestión Pública, Actores e Institucionalidad: Las Políticas Frente a la Pobreza en los ’90. Desarro. Económico 2000, 39, 597–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Social de la Nación (MDSN); Subsecretaría de Políticas Alimentarias. Informe Técnico PNSA; Ministerio de Desarrollo Social de la Nación (MDSN): Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cetrángolo, O.; Curcio, J.; Goldschmit, A.; Maurizio, R. Caracterización de la AUH con especial atención a su cobertura actual y posibilidades de expansión. In Anales LII Reunión Anual de la Asociación Argentina de Economía Política; AAEP: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini, L.; Bracco, J.; Falcone, G.; Galeano, L. Incidencia distributiva de la AUH; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA; ANSES: Buenos Aires, Argentina; Ministerio de Desarrollo Social de la Nación y Consejo de Coordinación de Políticas Sociales: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017.

- Gasparini, L.; Cruces, G. Las asignaciones universales por hijo en Argentina: Impacto, discusión y alternativas. Económica 2010, 56, 105–146. [Google Scholar]

- Edo, M.; Marchionni, M.; Garganta, S. Conditional Cash Transfer Programs and Enforcement of Compulsory Education Laws. The Case of Asignación Universal por Hijo in Argentina; Documento de trabajo 190; CEDLAS: La Plata, Argentina, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Edo, M.; Marchionni, M. The impact of a conditional cash transfer program on education outcomes beyond school attendance in Argentina. J. Dev. Eff. 2019, 11, 230–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulicino, C.; Gerenni, F.; Acuña, M. Primera Infancia en Argentina: Políticas a Nivel Nacional. CIPPEC. Programa de Protección Social y Programa de Educación. Área de Desarrollo Social. Doc. de Trabajo Nº 143. Available online: https://www.cippec.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/1166.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Filgueira, F.; Aulicino, C. La Primera Infancia en Argentina: Desafíos Desde los Derechos, la Equidad y la Eficiencia. Documento de Trabajo N° 130, CIPPEC. 2015. Available online: https://www.cippec.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/1259.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Gonzalez, M.S.; Santos, M.E. A Thousand Days—A programme for vulnerable early childhood in Argentina: Targeting, dropout risk factors and correlates of time to graduation. Child Care Health Dev. 2022, 49, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Desarrollo Social de la Nación (MDSN); Secretaria Nacional de Niñez, Adolescencia y Familia. Informe Interno. Primeros Años. Diciembre 2017; Ministerio de Desarrollo Social de la Nación (MDSN); Secretaria Nacional de Niñez, Adolescencia y Familia: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de Salta and UNICEF. Sistematización de la Experiencia de Acompañamiento Familiar en Contextos Rurales en Salta; Gobierno de Salta and UNICEF: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, M.S.; Santos, M.E. El programa Mil Días-Nación en perspectiva comparada con Mil Días San Miguel a dos años de su sanción. In Actualidad Económica; Universidad Nacional de Córdoba: Córdoba, Argentina, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional de Políticas Sociales (CNPS); Presidencia de la Nación. Informe de Evaluación 2016. Primeros Años Acompañamos la Crianza; 2016. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/politicassociales-publicaciones-primerosanios-informe-evaluacion_2016.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- CIPPEC (2018) and Municipalidad de San Miguel. Informe de Evaluación. Programa de Acompañamiento Familiar 1000 Días. Available online: https://www.cippec.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/CIPPEC-Informe-Final-Evaluación-Mil-D%C3%ADas-Municipio-de-San-Miguel.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Scartascini, C.; Tommasi, M. The Making of Policy: Institutionalized or Not? Am. J. Politi-Sci. 2012, 56, 787–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, P.; Tommasi, M. Un país sin rumbo. ¿Cómo se hacen las políticas públicas en Argentina. In El Juego Político en América Latina. ¿Cómo se Deciden las Políticas Públicas? Scartascini, C., Spiller, P.T., Stein, E., Tommasi, M., Eds.; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Capitulo 3; pp. 75–116. [Google Scholar]

- SIEMPRO, Sistema de Información, Evaluación y Monitoreo de Programas Sociales. Argentina. Presidencia de la Nación. Data from 2018–2019. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/politicassociales/siempro (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Coordinación de Primera Infancia, Niñez y Familia (CPINF); Secretaría de Salud: Municipio de San Miguel, Panama, 2017.

- UNICEF. Convention on the Rights of the Child for Every Child, Every Right. 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention#learn (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Heckman, J. Return on Investment in Birth-to-Three Early Childhood Development Programs. The Heckman Equation. Available online: https://heckmanequation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/F_ROI-Webinar-Deck_birth-to-three_091818.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- CEPAL-UNICEF. Maltrato infantil: Una dolorosa realidad puertas adentro. Desafíos 2009, 9. [Google Scholar]

- UN (United Nations). Study of Violence against Children; UN (United Nations): New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Maltrato Infantil. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). The World Health Organization’s Infant Feeding Recommendation; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Assessing the Iron Status of Populations; World Health Organisation (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Ministry of Health of Argentina. Los Controles de Salud. 2023. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud/crecerconsalud/primermes/controlesdesalud (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Horna, M.E.; Rocha, M.T.; Hartman, I.; Larroza, G.O.; Morales, S.; Blugerman, M.A.; Hernandez, D.O.; Dos Santos, L. Utilización de hierro como terapia preventiva de anemia ferropenica en niños menores de 2 años. Rev. Posgrado Via Cátedra Med. 2014, 216, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Minisitry of Health Argentina. Fierritas: Una Estrategia Para la Prevención de la Anemia Infantil por Deficiencia Nutricional de Hierro. Producción Nacional y Distribución de un Complemento Para Niños y Niñas de 6 a 24 Meses; Minisitry of Health Argentina: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2023.

- Ball, H.L. The Atlantic Divide: Contrasting U.K. and U.S. Recommendations on Cosleeping and Bed-Sharing. J. Hum. Lact. Off. J. Int. Lact. Consult. Assoc. 2017, 33, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.; Pease, A.; Blair, P. Bed-sharing and unexpected infant deaths: What is the relationship? Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2015, 16, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarvey, C.; McDonnell, M.; Hamilton, K.; O’regan, M.; Matthews, T. An 8 year study of risk factors for SIDS: Bed-sharing versus non-bed-sharing. Arch. Dis. Child. 2006, 91, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scragg, R.K.R.; Mitchell, E.A. Side sleeping position and bed sharing in the sudden infant death syndrome. Ann. Med. 1998, 30, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokutake, C.; Haga, A.; Sakaguchi, K.; Samejima, A.; Yoneyama, M.; Yokokawa, Y.; Ohira, M.; Ichikawa, M.; Kanai, M. Infant Suffocation Incidents Related to Co-Sleeping or Breastfeeding in the Side-Lying Position in Japan. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2018, 246, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, G.; Heckman, J.J. The Economics of Child Well-Being; No 18466, NBER Working Papers; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, M.C.; Rubio-Codina, M.; Schady, N. 70 to 700 to 70,000: Lessons from the Jamaica Experiment; IDB Working Paper No. IDB-WP-1230; Routledge: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Neighborhood | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total | % Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrufaldi | 0 | 46 | 22 | 43 | 20 | 131 | 12% |

| Don Alfonso | 0 | 29 | 41 | 28 | 14 | 112 | 10% |

| Mariló/San Ambrosio/Trujuy | 4 | 60 | 43 | 25 | 21 | 153 | 14% |

| Mitre | 41 | 55 | 47 | 43 | 20 | 206 | 19% |

| Obligado | 17 | 41 | 31 | 46 | 20 | 155 | 14% |

| San Miguel Centro | 0 | 24 | 42 | 48 | 19 | 133 | 12% |

| Santa Brígida | 28 | 37 | 38 | 41 | 21 | 165 | 15% |

| Sarmiento | 0 | 0 | 16 | 35 | 5 | 56 | 5% |

| Total | 90 | 292 | 280 | 309 | 140 | 1111 | 100.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonzalez, M.S.; Santos, M.E. Sustainable Cities, Smart Investments: A Characterization of “A Thousand Days-San Miguel”, a Program for Vulnerable Early Childhood in Argentina. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612205

Gonzalez MS, Santos ME. Sustainable Cities, Smart Investments: A Characterization of “A Thousand Days-San Miguel”, a Program for Vulnerable Early Childhood in Argentina. Sustainability. 2023; 15(16):12205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612205

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzalez, Maria Sol, and Maria Emma Santos. 2023. "Sustainable Cities, Smart Investments: A Characterization of “A Thousand Days-San Miguel”, a Program for Vulnerable Early Childhood in Argentina" Sustainability 15, no. 16: 12205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612205

APA StyleGonzalez, M. S., & Santos, M. E. (2023). Sustainable Cities, Smart Investments: A Characterization of “A Thousand Days-San Miguel”, a Program for Vulnerable Early Childhood in Argentina. Sustainability, 15(16), 12205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151612205